Description

INCREASE SAVINGS

January

2015

By:

Kristen

Berman

of

Irrational

Labs

. OVERVIEW................................................4

THE

PROBLEM………….…………………………….6

RULE

OF

THUMB…………................………....9

MENTAL

ACCOUNTING.………...................13

PRE-â€COMMITMENT.………………………...…..16

OPPORTUNITY

COST

NEGLECT…….…….….17

FAST

FEEDBACK……………...………………..…..19

Table of

Contents

ACHIEVABLE

GOALS……………...……………...21

CHANGE

THE

MINDSET……………...…….…..24

PUT

FRICTION

IN

THE

RIGHT

PLACES……..26

CONCLUSION………………………………...……..28

WORKS

CITED…………………………….....……..30

2

.

METLIFE

FOUNDATION

Since

its

founding

in

1976,

MetLife

Foundation

has

provided

more

than

$530

million

in

grants

and

$100

million

in

program-â€related

investments

to

nonprofit

organizations.

The

MetLife

Foundation

believes

that

affordable,

accessible

and

well-â€designed

financial

services

can

transform

the

lives

of

those

in

need,

and

have

committed

$200

million

over

the

next

five

years

to

advancing

this

effort

around

the

world.

The

foundation

has

built

its

vision

for

global

financial

inclusion

on

three

powerful

pillars:

Access

and

Knowledge,

Access

to

Services

and

Access

to

Insights.

IRRATIONALLABS

IRRATIONALLABS

Led

by

famed

behavioral

economist

Dr.

Dr.

Dan

Ariely

and

Led

by

famed

behavioral

economist

Dan

Ariely

and

founder

Kristen

Berman,

Irrational

Labs

is

a

is

a

nonprofit

that

founder

Kristen

Berman,

Irrational

Labs

nonprofit

that

applies

behavioral

economics

findings

to

findings

marketing,

applies

behavioral

economics

product,

to

product,

and

marketing,

and

organizational

design

problems.

By

organizational

design

problems.

By

understanding

human

decision

making

and

motivations,

Irrational

Lmotivations,

understanding

human

decision

making

and

abs

help

companies

create

compelling

value

propositions,

grow

their

Irrational

Labs

help

companies

create

compelling

value

customer

base

and

grow

ttheir

ccustomer

engaged.

keep

those

propositions,

keep

hose

ustomers

base

and

customers

engaged.

3

. I.

OVERVIEW…..….........…

A

group

of

researchers

studied

the

effects

of

peer

pressure

and

self-â€help

groups

on

savings

behavior

and

found

that

it

was

effective

at

helping

individuals

save

money.

1

The

experiments

were

conducted

in

Chile

with

low-â€income

micro-â€

entrepreneurs

who

earned

an

average

of

84,188

pesos

(175

USD)

per

month.

Sixty-â€

eight

percent

of

participants

did

not

have

a

savings

account

prior

to

the

study

and

were

required

to

sign

up

for

an

account

based

on

the

savings

group

they

were

assigned

to:

1. Savings

group

1

-â€

a

basic

savings

account

with

an

interest

rate

of

0.3%.

2. Savings

group

2

-â€

a

basic

savings

account

with

an

interest

rate

of

0.3%.

The

participants

were

also

part

of

a

self-â€help

peer

group,

where

they

could

voluntarily

announce

their

savings

goals

and

monitor

their

progress

on

a

weekly

basis.

3. Savings

group

3

-â€

a

high

interest

rate

account

with

a

rate

of

5%

(the

best

available

rate

in

Chile).

The

study

found

that

participants

that

were

part

of

the

self

help

peer

group

(savings

group

2)

deposited

3.5

times

more

than

others

and

their

average

savings

balance

was

almost

double

of

those

who

held

a

basic

savings

account.

The

high

interest

rate

had

a

very

little

effect

on

most

participants.

To

further

understand

why

self-â€help

peer

groups

work,

a

second

study

was

con-â€

ducted

a

year

later.

The

participants

were

divided

into

two

groups.

One

group

received

text

messages

that

notified

participants

of

their

progress

and

the

progress

of

other

participants.

They

were

assigned

a

savings

buddy

with

whom

they

would

meet

on

a

regular

basis

and

who

would

hold

them

accountable

to

their

savings

goals.

1

2

Mast,

Meier,

Pomeranz,

2012.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w18417.pdf

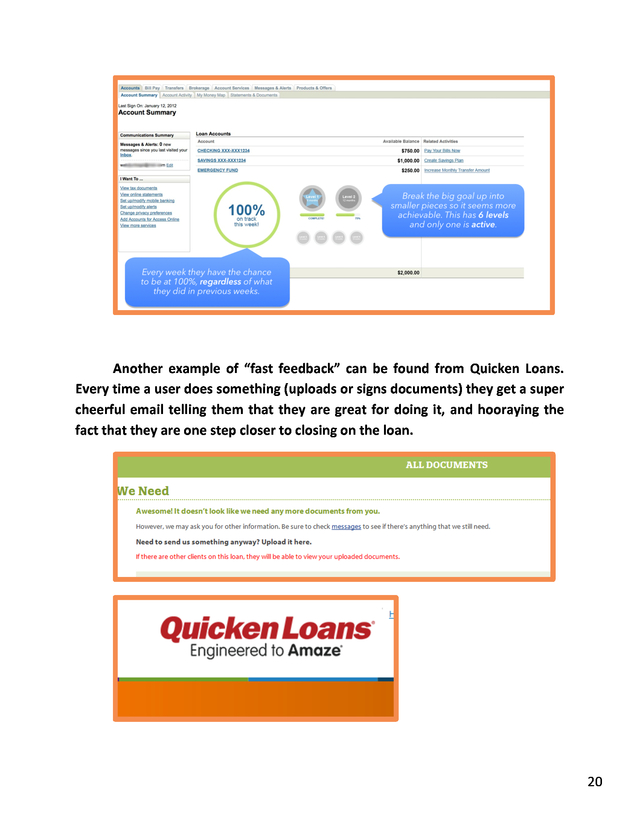

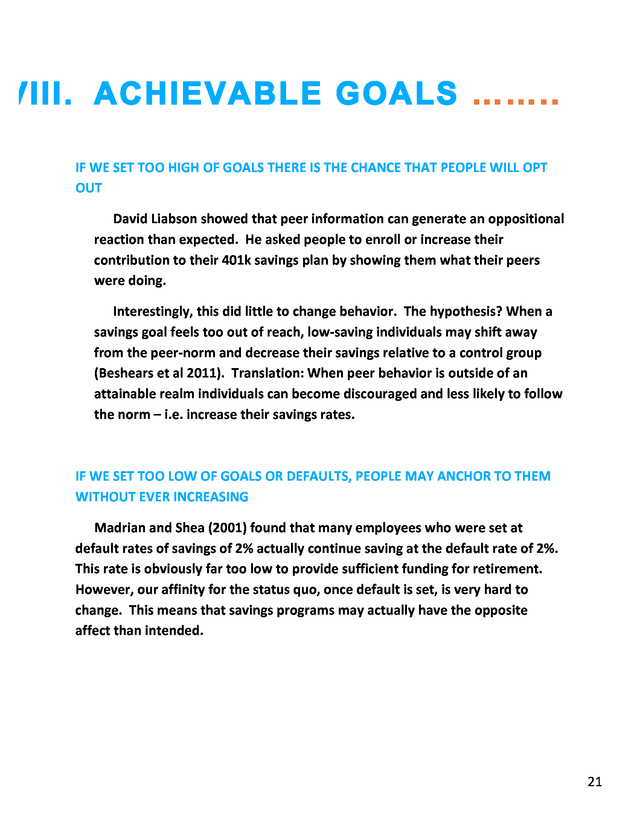

http://www.dartmouth.edu/~alusardi/Papers/American_Life_Panel.pdf

4

.

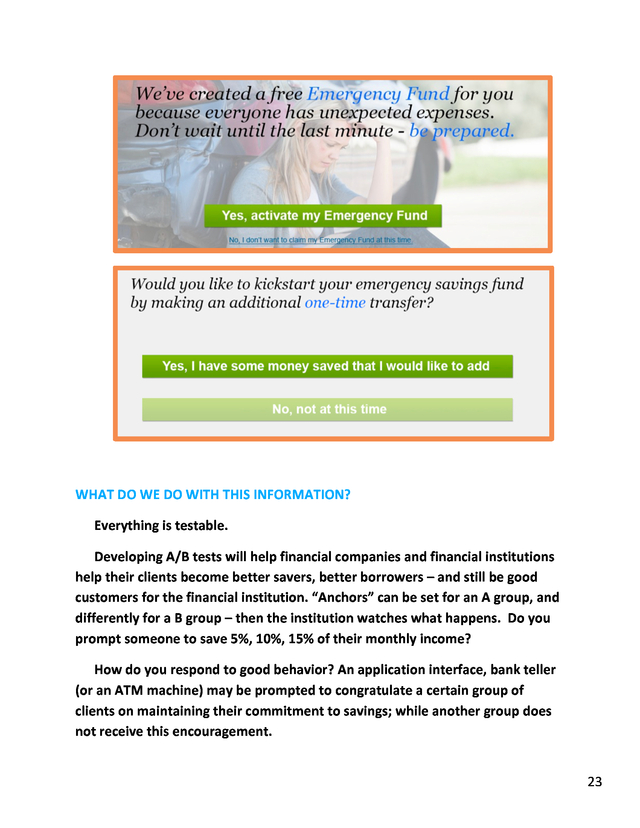

The other group only received text messages that notified participants of their progress and the progress of other participants. The results of the second experiment found that having a savings buddy made very little difference and that receiving text messages was just as effective. As noted by the researchers, having peer groups was an effective commitment device to achieving savings goals but meeting in-â€person was not necessary. Receiving text messages indicating their progress and the progress of the peers was just as effective. Small changes, big effects As this example shows, and many other academics and banks have proven, small changes to the design of a savings scheme can have big effects on participation rates. In the case above, a simple SMS message that reported and reminded them how they were doing and how their peers were doing was enough to increase savings. Below we summarize some of the main principles that should be used when designing a savings account, and in particular, many of our examples will be about designing an emergency savings fund. An emergency savings fund is the first step in savings and something many low-â€income people (and people with low financial literacy) are lacking. These principles and the approach can be used by Fin-â€tech companies to encourage good financial behaviors, policy makers to inform policy decisions and banks to increase the financial well-â€being of their customers. 5 . II. THE PROBLEM.……… Financial health in the US is at an all-â€time low. Almost half of all households have less than three months worth of savings, and less than 30% feel confident they will have enough money to cover their basic living expenses (Helman 2014). Unfortunately, the current approach to solving our financial health problems in America is not working. In order to address this massive and growing problem, we need to take a different approach, a behavioral one. Until recently, the primary approach to fix financial health has been to improve financial literacy. Lusardi and Mitchell (2007)2 and Lusardi and Tufano (2009), found incredibly low levels of financial literacy in the US population – this includes the inability to understand basic concepts such as the importance of retirement savings, and poor judgment in borrowing-â€decisions. Given this information, solution designers hypothesized that if we could only teach people the right things to do with their money, they would be more responsible with it. And, thus the US spent $670 million in financial education training programs (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau 2013). However, time and again, academic experiments have proven that information alone does not sufficiently motivate positive decision-â€making (Fernandes et al 2014)3. Most Americans know that they should quickly pay down debt, put more money toward emergency and retirement savings, and spend less on unnecessary items. However, psychologists have demonstrated that cognitive hurdles such as a lack of self-â€control, hyperbolic-â€discounting and general optimism-â€bias, prevent this. Instead, if we have money readily available we find it hard to make decisions that positively impact our future. (Benhabib, Bisin, Schotter, 2009)4 2 http://www.dartmouth.edu/~alusardi/Papers/American_Life_Panel.pdf http://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.2013.1849 4 http://www.nyu.edu/econ/user/bisina/GEB%20BBS.pdf 3 6 . 7 . A BEHAVIORALLY LED APPROACH to increase savings will fundamentally look at ways to make money feel less available by: • Making it easier to save by intervening at the point of decision (e.g., automating a savings deduction from paycheck) • Increasing general motivation to save through reward substitution and incentive design (e.g., creating a lottery type system associated with saving deposits) • Changing a person’s mindset about savings and what it means to them. (E.g., personally identifying as the kind of mom who prepares for their child’s college tuition) 8 . III. RULE OF THUMB………… People make a tremendous number of decisions that involve money every day. We decide whether we should buy coffee, take public transportation, if we should get the soup or the steak sandwich. However, the reality is that financial decisions are incredibly complex. Consider, for example, the simple case of a buying a cup of coffee for $4. To carry out this decision properly, we need to think about not only the pleasure that we will get from the cup of coffee but also the opportunity cost — what we will give up for the pleasure of the coffee. Only if the expected pleasure of the coffee is larger than the opportunity-â€cost should we spend the money. This could be an incredibly hard decision. So how do we make these seemingly simple, but ultimately very complex decisions? Sometimes we don’t. For example, instead of imagining all the ways we could substitute a coffee with something cheaper or the ways in which we could use $4 that would provide more utility, we buy the coffee. We generally don’t consider the short-â€term utility of the purchase, relative to the long-â€term utility of saving the money or spending it differently. Instead, we simply repeat our past behavior. 9 . WHAT SHOULD WE BE DOING? One solution is to educate people more on how to make these complex tradeoffs at the point of decision. But this sounds tiring. If we weighed the cost and benefits of everything, all the time, our lives would be stressful and busy. Besides just remembering how to do this -†which is difficult in itself -†imagine the poor coffee buyer who would have to pull out a notepad before purchasing his cup of coffee. Now imagine this process for a much more complex financial decision, like how much to save for retirement. In order to calculate an optimal personal savings rate, we have to make assumptions on very uncertain outcomes, like future rates of return, income flows, retirement plans, and health care needs. People do not do this. In a survey of faculty and staff at the University of Southern California, 58 percent spent less than one hour determining their contribution rate and investment elections in a retirement account (Benartzi and Thaler 1999)5. So how do we make these financial decisions? The results from multiple experiments show that people rely on simplified rules of thumb — heuristics — to help us solve these complex problems. 5 http://wolfweb.unr.edu/homepage/pingle/Teaching/BADM%20791/Week%209%20Behavioral%20Microeconomic s/Benartzi-â€Thaler%20Biased%20Savings%20Behavior.pdf 10 . For example, Ideas 42 ran a test on teaching a financial curriculum to two groups of people. One was a standard literacy curriculum. And one was based on strong rules-â€of-â€thumb. The rules-â€of-â€thumb training increased the fraction of people keeping accounts and those separating household and business finances by 11 percentage points each. It also raised sales during bad weeks by 18.5% relative to the comparison group (Ideas42 n.d.).6 Below are four proven rules of thumb we should consider as we design a retirement savings program, application or experience (Benartzi Thaler 2007). • SAVING THE MAX: When there was a max set at 16% contribution, 21 percent of new hires deferred 16 percent of their income. After moving the max to 100%, 5 percent deferred 16 percent and 7 percent deferred 6 http://www.ideas42.org/financial-â€heuristics/ 11 . more than 16 percent. Thus, the share of employees saving at least 16 percent decreased from 21 to 12 percent (Benartzi Thaler 2007). • SAVING THE MIN TO GET THE MATCH: Common rule of thumb is to contribute to a retirement account the minimum necessary to get the full employer match. For example, if the employer matches employees’ contributions up to 6 percent of pay, then many employees contribute 6 percent (Benartzi Thaler 2007). • SAVING IN MULTIPLES OF FIVE: Hewitt Associates found that the distribution of contribution rates spikes at multiples of five percent, even though there were no specific thresholds of either five or 10 (Benartzi Thaler 2007). • SAVINGS USING THE 1/N RULE: We divide evenly, when possible. Imagine having a sum ($100) and you can put however much money you want into N number of buckets. If you have four buckets (n=4), 65% of the people use the 1/nth rule. But, if you have three (n=3) to divide $100, 1/n rule is only used by 18 percent of the participants (Benartzi Thaler 2007). 12 . IV. MENTAL ACCOUNTING…. We mentally assign money to different categories of spending. And while this is just a mental exercise and nothing is actually different about the money, we spend money according to these categories. In addition, money that we haven’t assigned, feels different than money we have assigned (Thaler 1985). If you were to get a refund or ‘money back’ from a clothing merchant, would you use this money for rent or would you use this money to spend in the same category (clothing) where the money was returned from? Most people would be more willing to use this money towards clothing. Within banking, how we manage our money between checking, savings, loan and bill accounts displays our affinity for mental accounting. Why do we leave money in a checking account and also have high interest loans? This is not the optimal or rational decision for us. However, doing something different, like paying off all high interest loans and having very little money in checking, may feel more irresponsible. In both of these cases, people are relating to money like it is not fungible. Once it is tagged for something, we view it as difficult to use it for another purpose. And, if it is not tagged for something, we consider it open hunting season and are more willing to spend it freely. There are two different solutions we could use to deal with our tendencies around mental accounting. First, we could try to create something with perfect fungibility. In this case, we would ask people to think about all the ways they could use the money before they spent it, so as to not pigeon-â€hole themselves into one category. The other solution is to harness our tendency to do mental accounting and optimize decision-â€making within this tendency. The behavioral economics approach leans toward the latter solution. 13 . HOW WOULD WE DO THIS? To increase general financial outcomes using mental accounting, a bank would want to create multiple spending and multiple savings accounts with different names. As soon as someone opened a checking or savings accounts, they may opt into having additional ‘fake-â€accounts’ opened for them. These would have names ranging from “Rainy Day Fund’ to ‘Retirement Fund’ to ‘Kids College’. It may not even matter if these were actual new banking accounts. The main criteria is that the user thinks they are different buckets. The visual display would represent this mental accounting and each new account would have running balances and goals. SmartyPig does something similar to this with their goal interface, below. WHAT WOULD THIS LOOK LIKE AT A BANK? Imagine that each bank creates an “Emergency Fund” account within a user’s checking or savings account. Anything that is put into the “Emergency Fund” is visibly hidden from checking account balance. This emergency fund is treated like a new account in the user’s eyes. 14 . To view what an end to end experience could look like for a bank’s interface, please download the full visual mock ups on irrationallabs.org. 15 . V. PRE-COMMITMENT……. Getting people to pre-â€commit to a goal can help with self-â€control. In one study, students were given the opportunity to create their own deadlines for coursework. The students could pre-â€commit to deadlines: “I want to turn my papers in at different points during the semester”. Or, students could choose to turn in all of their coursework at the end of the semester. The students who choose to set deadlines for themselves received higher grades. Why? It seems they recognized they might procrastinate. By making this pre-†commitment at the start, they were able to spread work out and avoid the impulsive (and tempting) distractions that may have plagued the other students. (Ariely, Wertenbroch, 2002)7 Pre-â€commitment is a tool to help people follow through on decisions. One does this by making a decision on behalf of their future self. Instead of relying on ourselves to be great people, we make it harder for our future self to mess up. In this case, one could pre-â€commit to re-â€occurring transfers, increasing transfer amounts over time or answering questions before withdrawing from their savings. These commitments would be made at the start and be thoughtful and rational decisions. Like the students who set their own deadlines, this may help people avoid temptation when it hits. 7 http://dl1.cuni.cz/pluginfile.php/95343/mod_resource/content/0/Ariely_2002_procrastination.pdf 16 . VI. OPPORTUNITY COST NEGLECT…… “Thinking of money in the right way is thinking of opportunity costs in the right way, which is impossible,” Dan Ariely said. Instead Ariely said humans think of money in relative terms. Given this, how could we present the decision to improve your financial situation in relative terms? (Ariely, 2007)8 Let’s just look at the actual moment when someone decides to save or not. We have three choices. • We can do ‘opt out’ and default them into the plan. The default is to take no action and join the plan. • We can do ‘opt in’ and let them decide. The default is to take no action and not join the plan. • We can present the choice as an ‘active choice’ and they must choose one or the other. There is no set default. In the context of savings or other big decisions, many times it is not possible to design an ‘opt out’ experience due to legal reasons, even though research proves it will result in the highest amount of savings. In these cases, we can present the opportunity cost of not saving by using the ‘active choice’ approach. We can ask the users to view the decisions in a relative manner and actively consider the alternatives. For example, in one study workers at a certain company were asked to make an active decision whether or not to join their savings plan. Employees were forced to check a “yes” or a “no” box for participation in this plan. In this study, participation rates increased by about 28 percentage points compared to 8 http://danariely.com/the-â€books/excerpted-â€from-â€chapter-â€1-â€%E2%80%93-â€the-â€truth-â€about-â€relativity-â€2/ 17 . standard opt-â€in enrollment procedures. The ability to understand and use numbers is key to making good financial decisions (Choi et al 2005). BELOW ARE THREE IDEAS FOR ‘CALLS TO ACTION’ WITHIN AN APPLICATION EXPERIENCE. Bank interface “Yes, activate my emergency fund” or “No, I don’t want to claim my Emergency Fund at this time” Insurance companies “Insure against emergencies” or “Take my chances” 18 . VII. FAST FEEDBACK………….. If you binge on pizza and soda and then 1 week later gain a pound, it would be very difficult to track the pound back to your pizza and soda binge. This is the case for most behaviors. If we do a new behavior, like junk food binging, and the reward (or in this case punishment) for the behavior is delayed at all, it is very difficult to learn from your actions. Imagine a world where you took all of your tests throughout the school year, but only got the grades for them at the end. How likely is it that your study methods would improve? Unlikely. There would be no feedback after a test indicating that your studying methods worked or did not work. How should we apply this insight to savings? If we only reward or acknowledge a user when they hit a large milestone, we are delaying feedback in a way that makes it difficult to learn. So while our savers could easily look down at their bank accounts to monitor progress, our strategy must frequently acknowledge the user’s progress after they do something positive and create optimal reinforcement. Below is an example of how a behaviorist would approach showing progress on an emergency savings goal. 19 . Another example of “fast feedback” can be found from Quicken Loans. Every time a user does something (uploads or signs documents) they get a super cheerful email telling them that they are great for doing it, and hooraying the fact that they are one step closer to closing on the loan. 20 . VIII. ACHIEVABLE GOALS …….. IF WE SET TOO HIGH OF GOALS THERE IS THE CHANCE THAT PEOPLE WILL OPT OUT David Liabson showed that peer information can generate an oppositional reaction than expected. He asked people to enroll or increase their contribution to their 401k savings plan by showing them what their peers were doing. Interestingly, this did little to change behavior. The hypothesis? When a savings goal feels too out of reach, low-â€saving individuals may shift away from the peer-â€norm and decrease their savings relative to a control group (Beshears et al 2011). Translation: When peer behavior is outside of an attainable realm individuals can become discouraged and less likely to follow the norm – i.e. increase their savings rates. IF WE SET TOO LOW OF GOALS OR DEFAULTS, PEOPLE MAY ANCHOR TO THEM WITHOUT EVER INCREASING Madrian and Shea (2001) found that many employees who were set at default rates of savings of 2% actually continue saving at the default rate of 2%. This rate is obviously far too low to provide sufficient funding for retirement. However, our affinity for the status quo, once default is set, is very hard to change. This means that savings programs may actually have the opposite affect than intended. 21 . EXAMPLE: APPLYING THIS TO EMERGENCY FUND SET UP When a product or application is helping a user set up and maintain an emergency fund, how should the contribution amount be determined? Below are three things to consider when setting savings anchors: • CHOICE ARCHITECTURE: Contribution rates should be different for different customers, depending the current amount the customer has in the bank, their ability and desire to grow a rainy day fund quickly or over time. The customer must not choose this amount, it should be recommended to them. • PERIODICITY: How frequently should a saver transfer money to savings? The question of weekly vs monthly should be driven by when the customer has an inflow of money. If they have an inflow of money (get paid) on a weekly basis, we can create a weekly pull into the emergency fund. If it is monthly, we should recommend only monthly pulls into the fund. • COMMIT: Customers should actively commit and accept the savings decision. If they do not, they may not internalize the decision and be more willing to make changes when short term needs arise. 22 . WHAT DO WE DO WITH THIS INFORMATION? Everything is testable. Developing A/B tests will help financial companies and financial institutions help their clients become better savers, better borrowers – and still be good customers for the financial institution. “Anchors” can be set for an A group, and differently for a B group – then the institution watches what happens. Do you prompt someone to save 5%, 10%, 15% of their monthly income? How do you respond to good behavior? An application interface, bank teller (or an ATM machine) may be prompted to congratulate a certain group of clients on maintaining their commitment to savings; while another group does not receive this encouragement. 23 . IX. CHANGE THE MINDSET…. The Duke Center for Advanced Hindsight, led by Dan Ariely and in partnership with the Gates foundation, ran a study this year in Kumor, South Africa to get people to save. (Akbas, Ariely, Robalino, Weber, 2014)9 The study was designed for people in extreme poverty. The team tested many different hypotheses on what would increase general savings within families. The experiment conditions included: • MONETARY INCENTIVES. It provided small (10%) and large (40%) savings matches in hopes that people would be motivated by the savings matches enough to become active savers. • TRIGGERS. SMS reminders were sent on a weekly basis. The idea with reminders is that it is not that people don’t want to save or cannot save, it is that they forget to save on a regular basis. • ACCOUNTABILITY. SMS messages were sent from the saver’s children. This personalized message was aiming to provide a deep sense of accountability. • IDENTITY. The Saver was given a cheap (fake) gold-â€colored coin. The people in this condition were instructed to put this cheap (fake) gold colored coin somewhere special, like a jewelry box. They were also asked to scratch off a tic mark (which was on the coin) every time they saved. The coin had a set number of tic marks on it that the Saver could easily scratch off. 9 http://sites.duke.edu/merveakbas/files/2014/08/How-â€to-â€help-â€the-â€poor-â€.pdf 24 . The winning intervention creating the biggest savers was a surprise, even to the team of researchers. The gold-â€colored coin beat all the other conditions. How did this happen? How did a fake coin beat out a savings match to increase savings rates? At this point, the researchers have multiple hypotheses as to the root cause. A very plausible one, which we put forth here, is that the coin created a mindset change in the family. This physical object was a conversation starter around savings. Savings now had a constant place within the family and instilled a saving identity. The researchers believe that the coin helped people identify as people who save money and consequently, they think, increase their overall savings. In the US banking world we can seek to achieve a similar mindset shift. Some ideas to encourage this mindset shift: • Create a Banking PLUS membership. This is an elite membership to the bank that everyone is given upon signing up, but to maintain must contribute a minimum amount to their savings every month. Instead of monetary benefits to membership, the user’s debit cards are branded and their ATM screen is branded with PLUS. • In the progress meter online, give people ‘badges’ who have activated an emergency fund. These badges will help create an identity of being a saver. If someone has not activated this emergency fund, the progress bar will be obviously incomplete and the badge will be noticeably missing. On the flip-â€side, if someone does activate the emergency fund, they will become a saver and the progress meter and badges will be constant in their account view. 25 . X. PUT FRICTION IN THE RIGHT PLACES…………... WHY DO PEOPLE SAVE? One may think that the savers have a strong preference for the future, or that they are more conservative with risk. This may be true sometimes. However, experiments have found that a better indictor for likelihood to save is the friction required to complete a savings action. One extreme example of reluctance to join an attractive retirement plan comes from the United Kingdom. (Benartzi, Thaler 2007) Some defined benefit plans in the UK do not require any employee contributions and are fully paid for by the employer. However, to join, an employee must take some action. So how many join these seemingly magical plans? Only half. Half of employees signed up, even though there was nothing but upside for them. Why? One can only guess it takes too much work. In another case, when automatic enrollment was adopted, enrollment of new employees jumped to 90 percent immediately – from a low 20 percent. Automatic enrollment has two effects: participants join sooner, and more participants join eventually. Given these examples, we want to make it frictionless to create a savings plan. However in the current paradigm, all products and applications have the concept of ‘creating an account’. In the banking world, you are asked to ‘open an account.’ To the person who doesn’t like to put in ANY effort, ‘opening an account’ feels like a lot of effort! For products and services that are trying to get people to set up accounts, we recommend avoiding the concept of ‘opening’ an 26 . account. Instead, we can use the word, ‘Activate’ to signal that the person already has the account and they just need to (easily) turn it on. But, on the reverse side, adding friction is a good thing when it prevents a behavior that we don’t want. For example, how do you prevent people from taking money out of their savings plan? In this case, we do want to add friction. See below for the type of questions we can add before the user is able to take out their savings. This increased the amount of effort needed to perform the desired action and thereby may decrease the number of people who take this action out of impulse. 27 . XI. DISCUSSION.....…………... These are complex decisions. Should we just let users decide how much to save by themselves and not interfere with the decision making process at all? Benartzi and Thaler tested this question in a clever manner. They decided to study the very people who actively chose to opt out of a professionally-â€made investment plan in favor of creating their own custom investment plan. To study these people, they asked them to rate the returns of both plans -†theirs and the professionally-â€designed plan. The question: After seeing the returns, which one do you like more? Self-â€constructed portfolios received the lowest average rating, 2.75, and the professionally-â€managed portfolios received the significantly higher mean-†rating of 3.50. This gives us an indication that even the people who have the initial desire to control their retirement liked their portfolio less than the professionally managed portfolio plan and they agree that they can benefit from additional help. This brings out a bigger point to our discussion. If we let people do as they please with their finances, we should not be surprised if they fail. The idea of letting people make decisions without any help is proven to be misguided. The evidence, time and again, proves that this is stressful for the consumer and is very likely to put them in an objectively worse financial situation. 28 . TO DRIVE THE SUCCESS OF A SAVINGS PLATFORM, WE ENCOURAGE PRODUCT DESIGNERS AND FINANCIAL LEADERS TO CREATE: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) 8) Rules of thumb Mental Accounting Pre – Commitment Clear Opportunity Costs Fast Feedback Achievable Goals Mindset Changes Friction in the right places 29 . XII. WORKS CITED...…......... Ariely (2007) Predictably Irrational. Akbas, Ariely, Robalino, Weber. (2014). How to help the poor to save a bit: Evidence from a field experiment in Kenya. Department of Economics, Duke University. Ariely, Wertenbroch. (2002) Procrastination, Deadlines, Performance: Self Control by Pre-â€commitment. Psychological Science. Vol 13, No. 3. Benartzi, S., & Thaler, R. H. (1999). Risk Aversion or Myopia? Choices in Repeated Gambles and Retirement Investments. Management Science, 45(3), 364-â€381. Benartzi, S., & Thaler, R. H. (2007). Heuristics and Biases in Retirement Savings Behavior. Journal Of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), 81-â€104. Beshears, J., Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., Madrian, B. C., & Milkman, K. L. (2011). The Effect of Providing Peer Information on Retirement Savings Decisions. Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., Madrian, B., & Metrick, A. (2005). Optimal Defaults and Active Decisions. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2013). Navigating the Market. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Retrieved from http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201311_cfpb_navigating-â€the-â€market-†final.pdf Fernandes, D., Lynch Jr, J. G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2014). Financial Literacy, Financial Education, and Downstream Financial Behaviors. Management Science. Helman, R. (2014). The 2014 Retirement Confidence Survey: Confidence Rebounds—for Those With Retirement Plans. EBRI Issue Brief, (397). 30 . Ideas42. Financial Heuristics. Ideas42.org. Retrieved from http://www.ideas42.org/financial-â€heuristics/ Kast, Meier, Pomeranz (2012). Under-â€savers anonymous: Evidence on self help groups and peer pressure as a savings commitment device. National Bureau of Economics research. Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2007). Baby boomer retirement security: The roles of planning, financial literacy, and housing wealth. Journal of monetary Economics, 54(1), 205-â€224. Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2009). Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness (No. w14808). National Bureau of Economic Research. Madrian, B. C., & Shea, D. F. (2001). The Power of Suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) Participation and Savings Behavior. Quarterly Journal Of Economics, 116(4), 1149-â€1187. Thaler, R. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing science, 4(3), 199-â€214. 31 .

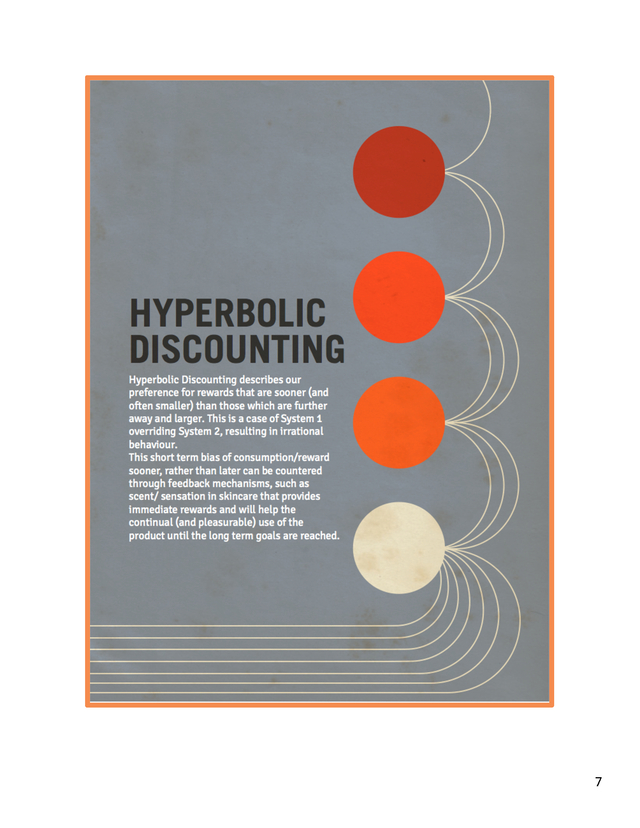

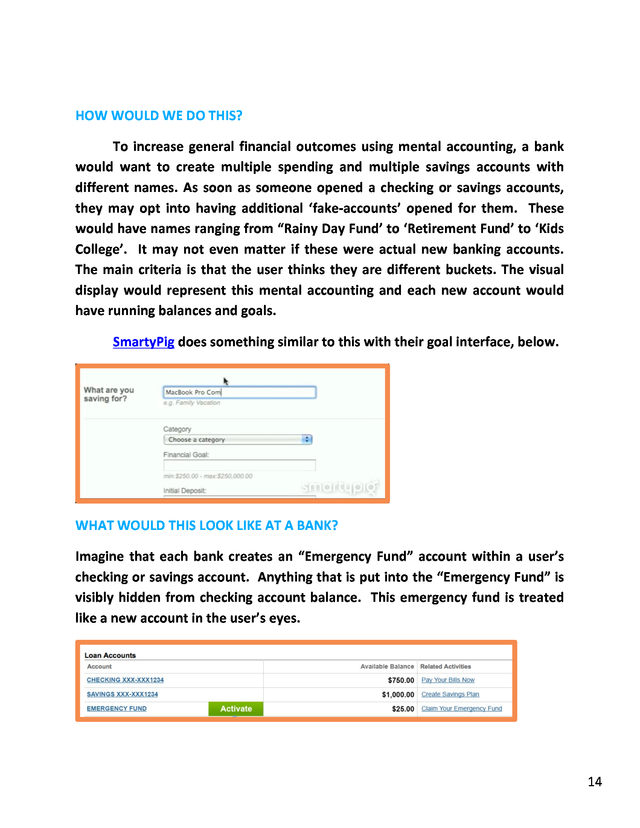

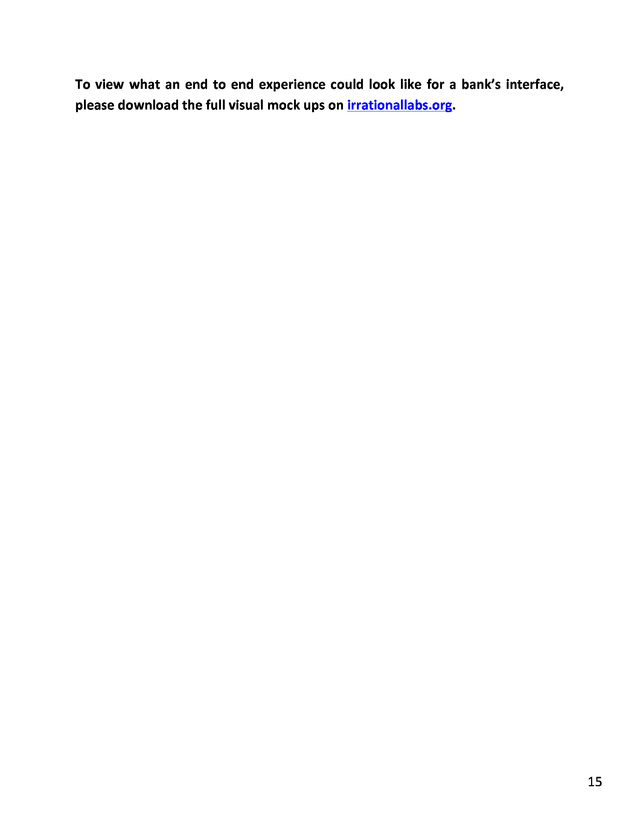

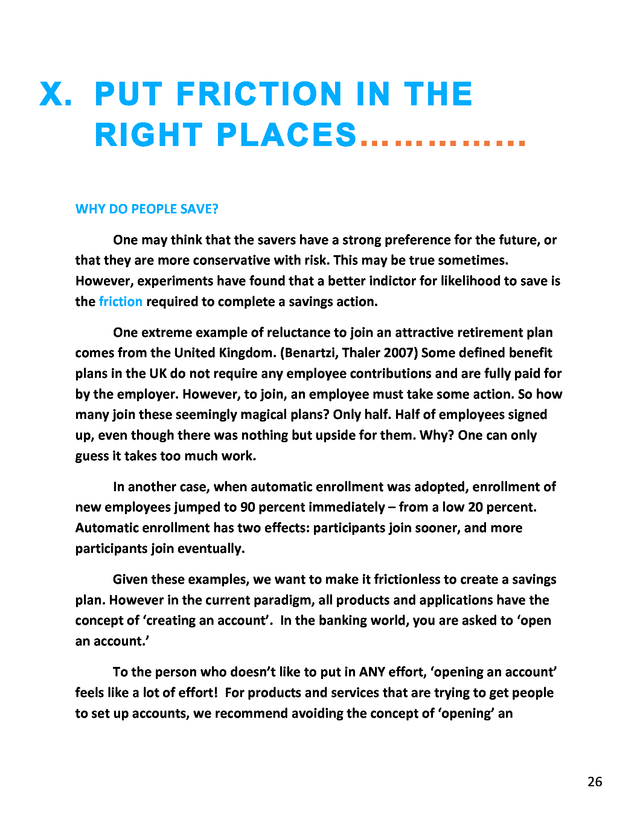

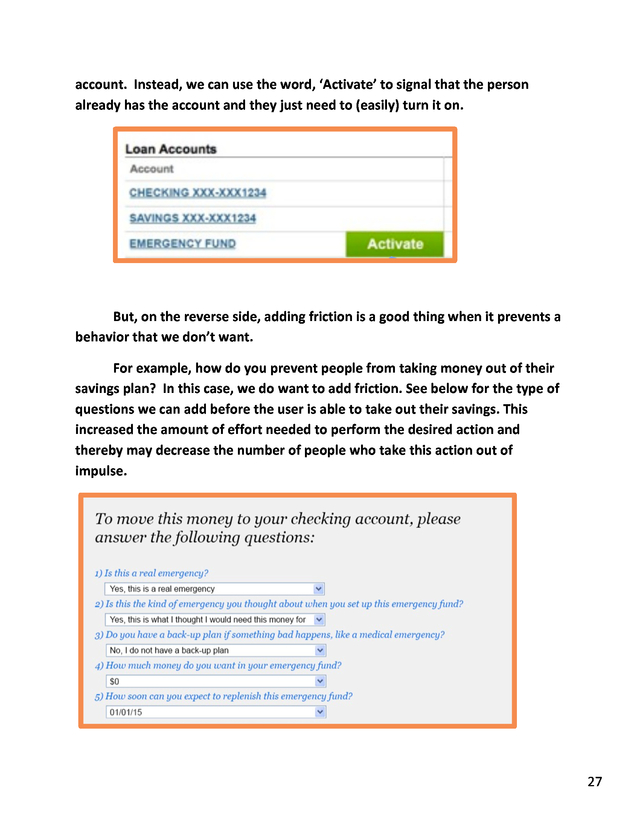

The other group only received text messages that notified participants of their progress and the progress of other participants. The results of the second experiment found that having a savings buddy made very little difference and that receiving text messages was just as effective. As noted by the researchers, having peer groups was an effective commitment device to achieving savings goals but meeting in-â€person was not necessary. Receiving text messages indicating their progress and the progress of the peers was just as effective. Small changes, big effects As this example shows, and many other academics and banks have proven, small changes to the design of a savings scheme can have big effects on participation rates. In the case above, a simple SMS message that reported and reminded them how they were doing and how their peers were doing was enough to increase savings. Below we summarize some of the main principles that should be used when designing a savings account, and in particular, many of our examples will be about designing an emergency savings fund. An emergency savings fund is the first step in savings and something many low-â€income people (and people with low financial literacy) are lacking. These principles and the approach can be used by Fin-â€tech companies to encourage good financial behaviors, policy makers to inform policy decisions and banks to increase the financial well-â€being of their customers. 5 . II. THE PROBLEM.……… Financial health in the US is at an all-â€time low. Almost half of all households have less than three months worth of savings, and less than 30% feel confident they will have enough money to cover their basic living expenses (Helman 2014). Unfortunately, the current approach to solving our financial health problems in America is not working. In order to address this massive and growing problem, we need to take a different approach, a behavioral one. Until recently, the primary approach to fix financial health has been to improve financial literacy. Lusardi and Mitchell (2007)2 and Lusardi and Tufano (2009), found incredibly low levels of financial literacy in the US population – this includes the inability to understand basic concepts such as the importance of retirement savings, and poor judgment in borrowing-â€decisions. Given this information, solution designers hypothesized that if we could only teach people the right things to do with their money, they would be more responsible with it. And, thus the US spent $670 million in financial education training programs (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau 2013). However, time and again, academic experiments have proven that information alone does not sufficiently motivate positive decision-â€making (Fernandes et al 2014)3. Most Americans know that they should quickly pay down debt, put more money toward emergency and retirement savings, and spend less on unnecessary items. However, psychologists have demonstrated that cognitive hurdles such as a lack of self-â€control, hyperbolic-â€discounting and general optimism-â€bias, prevent this. Instead, if we have money readily available we find it hard to make decisions that positively impact our future. (Benhabib, Bisin, Schotter, 2009)4 2 http://www.dartmouth.edu/~alusardi/Papers/American_Life_Panel.pdf http://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.2013.1849 4 http://www.nyu.edu/econ/user/bisina/GEB%20BBS.pdf 3 6 . 7 . A BEHAVIORALLY LED APPROACH to increase savings will fundamentally look at ways to make money feel less available by: • Making it easier to save by intervening at the point of decision (e.g., automating a savings deduction from paycheck) • Increasing general motivation to save through reward substitution and incentive design (e.g., creating a lottery type system associated with saving deposits) • Changing a person’s mindset about savings and what it means to them. (E.g., personally identifying as the kind of mom who prepares for their child’s college tuition) 8 . III. RULE OF THUMB………… People make a tremendous number of decisions that involve money every day. We decide whether we should buy coffee, take public transportation, if we should get the soup or the steak sandwich. However, the reality is that financial decisions are incredibly complex. Consider, for example, the simple case of a buying a cup of coffee for $4. To carry out this decision properly, we need to think about not only the pleasure that we will get from the cup of coffee but also the opportunity cost — what we will give up for the pleasure of the coffee. Only if the expected pleasure of the coffee is larger than the opportunity-â€cost should we spend the money. This could be an incredibly hard decision. So how do we make these seemingly simple, but ultimately very complex decisions? Sometimes we don’t. For example, instead of imagining all the ways we could substitute a coffee with something cheaper or the ways in which we could use $4 that would provide more utility, we buy the coffee. We generally don’t consider the short-â€term utility of the purchase, relative to the long-â€term utility of saving the money or spending it differently. Instead, we simply repeat our past behavior. 9 . WHAT SHOULD WE BE DOING? One solution is to educate people more on how to make these complex tradeoffs at the point of decision. But this sounds tiring. If we weighed the cost and benefits of everything, all the time, our lives would be stressful and busy. Besides just remembering how to do this -†which is difficult in itself -†imagine the poor coffee buyer who would have to pull out a notepad before purchasing his cup of coffee. Now imagine this process for a much more complex financial decision, like how much to save for retirement. In order to calculate an optimal personal savings rate, we have to make assumptions on very uncertain outcomes, like future rates of return, income flows, retirement plans, and health care needs. People do not do this. In a survey of faculty and staff at the University of Southern California, 58 percent spent less than one hour determining their contribution rate and investment elections in a retirement account (Benartzi and Thaler 1999)5. So how do we make these financial decisions? The results from multiple experiments show that people rely on simplified rules of thumb — heuristics — to help us solve these complex problems. 5 http://wolfweb.unr.edu/homepage/pingle/Teaching/BADM%20791/Week%209%20Behavioral%20Microeconomic s/Benartzi-â€Thaler%20Biased%20Savings%20Behavior.pdf 10 . For example, Ideas 42 ran a test on teaching a financial curriculum to two groups of people. One was a standard literacy curriculum. And one was based on strong rules-â€of-â€thumb. The rules-â€of-â€thumb training increased the fraction of people keeping accounts and those separating household and business finances by 11 percentage points each. It also raised sales during bad weeks by 18.5% relative to the comparison group (Ideas42 n.d.).6 Below are four proven rules of thumb we should consider as we design a retirement savings program, application or experience (Benartzi Thaler 2007). • SAVING THE MAX: When there was a max set at 16% contribution, 21 percent of new hires deferred 16 percent of their income. After moving the max to 100%, 5 percent deferred 16 percent and 7 percent deferred 6 http://www.ideas42.org/financial-â€heuristics/ 11 . more than 16 percent. Thus, the share of employees saving at least 16 percent decreased from 21 to 12 percent (Benartzi Thaler 2007). • SAVING THE MIN TO GET THE MATCH: Common rule of thumb is to contribute to a retirement account the minimum necessary to get the full employer match. For example, if the employer matches employees’ contributions up to 6 percent of pay, then many employees contribute 6 percent (Benartzi Thaler 2007). • SAVING IN MULTIPLES OF FIVE: Hewitt Associates found that the distribution of contribution rates spikes at multiples of five percent, even though there were no specific thresholds of either five or 10 (Benartzi Thaler 2007). • SAVINGS USING THE 1/N RULE: We divide evenly, when possible. Imagine having a sum ($100) and you can put however much money you want into N number of buckets. If you have four buckets (n=4), 65% of the people use the 1/nth rule. But, if you have three (n=3) to divide $100, 1/n rule is only used by 18 percent of the participants (Benartzi Thaler 2007). 12 . IV. MENTAL ACCOUNTING…. We mentally assign money to different categories of spending. And while this is just a mental exercise and nothing is actually different about the money, we spend money according to these categories. In addition, money that we haven’t assigned, feels different than money we have assigned (Thaler 1985). If you were to get a refund or ‘money back’ from a clothing merchant, would you use this money for rent or would you use this money to spend in the same category (clothing) where the money was returned from? Most people would be more willing to use this money towards clothing. Within banking, how we manage our money between checking, savings, loan and bill accounts displays our affinity for mental accounting. Why do we leave money in a checking account and also have high interest loans? This is not the optimal or rational decision for us. However, doing something different, like paying off all high interest loans and having very little money in checking, may feel more irresponsible. In both of these cases, people are relating to money like it is not fungible. Once it is tagged for something, we view it as difficult to use it for another purpose. And, if it is not tagged for something, we consider it open hunting season and are more willing to spend it freely. There are two different solutions we could use to deal with our tendencies around mental accounting. First, we could try to create something with perfect fungibility. In this case, we would ask people to think about all the ways they could use the money before they spent it, so as to not pigeon-â€hole themselves into one category. The other solution is to harness our tendency to do mental accounting and optimize decision-â€making within this tendency. The behavioral economics approach leans toward the latter solution. 13 . HOW WOULD WE DO THIS? To increase general financial outcomes using mental accounting, a bank would want to create multiple spending and multiple savings accounts with different names. As soon as someone opened a checking or savings accounts, they may opt into having additional ‘fake-â€accounts’ opened for them. These would have names ranging from “Rainy Day Fund’ to ‘Retirement Fund’ to ‘Kids College’. It may not even matter if these were actual new banking accounts. The main criteria is that the user thinks they are different buckets. The visual display would represent this mental accounting and each new account would have running balances and goals. SmartyPig does something similar to this with their goal interface, below. WHAT WOULD THIS LOOK LIKE AT A BANK? Imagine that each bank creates an “Emergency Fund” account within a user’s checking or savings account. Anything that is put into the “Emergency Fund” is visibly hidden from checking account balance. This emergency fund is treated like a new account in the user’s eyes. 14 . To view what an end to end experience could look like for a bank’s interface, please download the full visual mock ups on irrationallabs.org. 15 . V. PRE-COMMITMENT……. Getting people to pre-â€commit to a goal can help with self-â€control. In one study, students were given the opportunity to create their own deadlines for coursework. The students could pre-â€commit to deadlines: “I want to turn my papers in at different points during the semester”. Or, students could choose to turn in all of their coursework at the end of the semester. The students who choose to set deadlines for themselves received higher grades. Why? It seems they recognized they might procrastinate. By making this pre-†commitment at the start, they were able to spread work out and avoid the impulsive (and tempting) distractions that may have plagued the other students. (Ariely, Wertenbroch, 2002)7 Pre-â€commitment is a tool to help people follow through on decisions. One does this by making a decision on behalf of their future self. Instead of relying on ourselves to be great people, we make it harder for our future self to mess up. In this case, one could pre-â€commit to re-â€occurring transfers, increasing transfer amounts over time or answering questions before withdrawing from their savings. These commitments would be made at the start and be thoughtful and rational decisions. Like the students who set their own deadlines, this may help people avoid temptation when it hits. 7 http://dl1.cuni.cz/pluginfile.php/95343/mod_resource/content/0/Ariely_2002_procrastination.pdf 16 . VI. OPPORTUNITY COST NEGLECT…… “Thinking of money in the right way is thinking of opportunity costs in the right way, which is impossible,” Dan Ariely said. Instead Ariely said humans think of money in relative terms. Given this, how could we present the decision to improve your financial situation in relative terms? (Ariely, 2007)8 Let’s just look at the actual moment when someone decides to save or not. We have three choices. • We can do ‘opt out’ and default them into the plan. The default is to take no action and join the plan. • We can do ‘opt in’ and let them decide. The default is to take no action and not join the plan. • We can present the choice as an ‘active choice’ and they must choose one or the other. There is no set default. In the context of savings or other big decisions, many times it is not possible to design an ‘opt out’ experience due to legal reasons, even though research proves it will result in the highest amount of savings. In these cases, we can present the opportunity cost of not saving by using the ‘active choice’ approach. We can ask the users to view the decisions in a relative manner and actively consider the alternatives. For example, in one study workers at a certain company were asked to make an active decision whether or not to join their savings plan. Employees were forced to check a “yes” or a “no” box for participation in this plan. In this study, participation rates increased by about 28 percentage points compared to 8 http://danariely.com/the-â€books/excerpted-â€from-â€chapter-â€1-â€%E2%80%93-â€the-â€truth-â€about-â€relativity-â€2/ 17 . standard opt-â€in enrollment procedures. The ability to understand and use numbers is key to making good financial decisions (Choi et al 2005). BELOW ARE THREE IDEAS FOR ‘CALLS TO ACTION’ WITHIN AN APPLICATION EXPERIENCE. Bank interface “Yes, activate my emergency fund” or “No, I don’t want to claim my Emergency Fund at this time” Insurance companies “Insure against emergencies” or “Take my chances” 18 . VII. FAST FEEDBACK………….. If you binge on pizza and soda and then 1 week later gain a pound, it would be very difficult to track the pound back to your pizza and soda binge. This is the case for most behaviors. If we do a new behavior, like junk food binging, and the reward (or in this case punishment) for the behavior is delayed at all, it is very difficult to learn from your actions. Imagine a world where you took all of your tests throughout the school year, but only got the grades for them at the end. How likely is it that your study methods would improve? Unlikely. There would be no feedback after a test indicating that your studying methods worked or did not work. How should we apply this insight to savings? If we only reward or acknowledge a user when they hit a large milestone, we are delaying feedback in a way that makes it difficult to learn. So while our savers could easily look down at their bank accounts to monitor progress, our strategy must frequently acknowledge the user’s progress after they do something positive and create optimal reinforcement. Below is an example of how a behaviorist would approach showing progress on an emergency savings goal. 19 . Another example of “fast feedback” can be found from Quicken Loans. Every time a user does something (uploads or signs documents) they get a super cheerful email telling them that they are great for doing it, and hooraying the fact that they are one step closer to closing on the loan. 20 . VIII. ACHIEVABLE GOALS …….. IF WE SET TOO HIGH OF GOALS THERE IS THE CHANCE THAT PEOPLE WILL OPT OUT David Liabson showed that peer information can generate an oppositional reaction than expected. He asked people to enroll or increase their contribution to their 401k savings plan by showing them what their peers were doing. Interestingly, this did little to change behavior. The hypothesis? When a savings goal feels too out of reach, low-â€saving individuals may shift away from the peer-â€norm and decrease their savings relative to a control group (Beshears et al 2011). Translation: When peer behavior is outside of an attainable realm individuals can become discouraged and less likely to follow the norm – i.e. increase their savings rates. IF WE SET TOO LOW OF GOALS OR DEFAULTS, PEOPLE MAY ANCHOR TO THEM WITHOUT EVER INCREASING Madrian and Shea (2001) found that many employees who were set at default rates of savings of 2% actually continue saving at the default rate of 2%. This rate is obviously far too low to provide sufficient funding for retirement. However, our affinity for the status quo, once default is set, is very hard to change. This means that savings programs may actually have the opposite affect than intended. 21 . EXAMPLE: APPLYING THIS TO EMERGENCY FUND SET UP When a product or application is helping a user set up and maintain an emergency fund, how should the contribution amount be determined? Below are three things to consider when setting savings anchors: • CHOICE ARCHITECTURE: Contribution rates should be different for different customers, depending the current amount the customer has in the bank, their ability and desire to grow a rainy day fund quickly or over time. The customer must not choose this amount, it should be recommended to them. • PERIODICITY: How frequently should a saver transfer money to savings? The question of weekly vs monthly should be driven by when the customer has an inflow of money. If they have an inflow of money (get paid) on a weekly basis, we can create a weekly pull into the emergency fund. If it is monthly, we should recommend only monthly pulls into the fund. • COMMIT: Customers should actively commit and accept the savings decision. If they do not, they may not internalize the decision and be more willing to make changes when short term needs arise. 22 . WHAT DO WE DO WITH THIS INFORMATION? Everything is testable. Developing A/B tests will help financial companies and financial institutions help their clients become better savers, better borrowers – and still be good customers for the financial institution. “Anchors” can be set for an A group, and differently for a B group – then the institution watches what happens. Do you prompt someone to save 5%, 10%, 15% of their monthly income? How do you respond to good behavior? An application interface, bank teller (or an ATM machine) may be prompted to congratulate a certain group of clients on maintaining their commitment to savings; while another group does not receive this encouragement. 23 . IX. CHANGE THE MINDSET…. The Duke Center for Advanced Hindsight, led by Dan Ariely and in partnership with the Gates foundation, ran a study this year in Kumor, South Africa to get people to save. (Akbas, Ariely, Robalino, Weber, 2014)9 The study was designed for people in extreme poverty. The team tested many different hypotheses on what would increase general savings within families. The experiment conditions included: • MONETARY INCENTIVES. It provided small (10%) and large (40%) savings matches in hopes that people would be motivated by the savings matches enough to become active savers. • TRIGGERS. SMS reminders were sent on a weekly basis. The idea with reminders is that it is not that people don’t want to save or cannot save, it is that they forget to save on a regular basis. • ACCOUNTABILITY. SMS messages were sent from the saver’s children. This personalized message was aiming to provide a deep sense of accountability. • IDENTITY. The Saver was given a cheap (fake) gold-â€colored coin. The people in this condition were instructed to put this cheap (fake) gold colored coin somewhere special, like a jewelry box. They were also asked to scratch off a tic mark (which was on the coin) every time they saved. The coin had a set number of tic marks on it that the Saver could easily scratch off. 9 http://sites.duke.edu/merveakbas/files/2014/08/How-â€to-â€help-â€the-â€poor-â€.pdf 24 . The winning intervention creating the biggest savers was a surprise, even to the team of researchers. The gold-â€colored coin beat all the other conditions. How did this happen? How did a fake coin beat out a savings match to increase savings rates? At this point, the researchers have multiple hypotheses as to the root cause. A very plausible one, which we put forth here, is that the coin created a mindset change in the family. This physical object was a conversation starter around savings. Savings now had a constant place within the family and instilled a saving identity. The researchers believe that the coin helped people identify as people who save money and consequently, they think, increase their overall savings. In the US banking world we can seek to achieve a similar mindset shift. Some ideas to encourage this mindset shift: • Create a Banking PLUS membership. This is an elite membership to the bank that everyone is given upon signing up, but to maintain must contribute a minimum amount to their savings every month. Instead of monetary benefits to membership, the user’s debit cards are branded and their ATM screen is branded with PLUS. • In the progress meter online, give people ‘badges’ who have activated an emergency fund. These badges will help create an identity of being a saver. If someone has not activated this emergency fund, the progress bar will be obviously incomplete and the badge will be noticeably missing. On the flip-â€side, if someone does activate the emergency fund, they will become a saver and the progress meter and badges will be constant in their account view. 25 . X. PUT FRICTION IN THE RIGHT PLACES…………... WHY DO PEOPLE SAVE? One may think that the savers have a strong preference for the future, or that they are more conservative with risk. This may be true sometimes. However, experiments have found that a better indictor for likelihood to save is the friction required to complete a savings action. One extreme example of reluctance to join an attractive retirement plan comes from the United Kingdom. (Benartzi, Thaler 2007) Some defined benefit plans in the UK do not require any employee contributions and are fully paid for by the employer. However, to join, an employee must take some action. So how many join these seemingly magical plans? Only half. Half of employees signed up, even though there was nothing but upside for them. Why? One can only guess it takes too much work. In another case, when automatic enrollment was adopted, enrollment of new employees jumped to 90 percent immediately – from a low 20 percent. Automatic enrollment has two effects: participants join sooner, and more participants join eventually. Given these examples, we want to make it frictionless to create a savings plan. However in the current paradigm, all products and applications have the concept of ‘creating an account’. In the banking world, you are asked to ‘open an account.’ To the person who doesn’t like to put in ANY effort, ‘opening an account’ feels like a lot of effort! For products and services that are trying to get people to set up accounts, we recommend avoiding the concept of ‘opening’ an 26 . account. Instead, we can use the word, ‘Activate’ to signal that the person already has the account and they just need to (easily) turn it on. But, on the reverse side, adding friction is a good thing when it prevents a behavior that we don’t want. For example, how do you prevent people from taking money out of their savings plan? In this case, we do want to add friction. See below for the type of questions we can add before the user is able to take out their savings. This increased the amount of effort needed to perform the desired action and thereby may decrease the number of people who take this action out of impulse. 27 . XI. DISCUSSION.....…………... These are complex decisions. Should we just let users decide how much to save by themselves and not interfere with the decision making process at all? Benartzi and Thaler tested this question in a clever manner. They decided to study the very people who actively chose to opt out of a professionally-â€made investment plan in favor of creating their own custom investment plan. To study these people, they asked them to rate the returns of both plans -†theirs and the professionally-â€designed plan. The question: After seeing the returns, which one do you like more? Self-â€constructed portfolios received the lowest average rating, 2.75, and the professionally-â€managed portfolios received the significantly higher mean-†rating of 3.50. This gives us an indication that even the people who have the initial desire to control their retirement liked their portfolio less than the professionally managed portfolio plan and they agree that they can benefit from additional help. This brings out a bigger point to our discussion. If we let people do as they please with their finances, we should not be surprised if they fail. The idea of letting people make decisions without any help is proven to be misguided. The evidence, time and again, proves that this is stressful for the consumer and is very likely to put them in an objectively worse financial situation. 28 . TO DRIVE THE SUCCESS OF A SAVINGS PLATFORM, WE ENCOURAGE PRODUCT DESIGNERS AND FINANCIAL LEADERS TO CREATE: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) 8) Rules of thumb Mental Accounting Pre – Commitment Clear Opportunity Costs Fast Feedback Achievable Goals Mindset Changes Friction in the right places 29 . XII. WORKS CITED...…......... Ariely (2007) Predictably Irrational. Akbas, Ariely, Robalino, Weber. (2014). How to help the poor to save a bit: Evidence from a field experiment in Kenya. Department of Economics, Duke University. Ariely, Wertenbroch. (2002) Procrastination, Deadlines, Performance: Self Control by Pre-â€commitment. Psychological Science. Vol 13, No. 3. Benartzi, S., & Thaler, R. H. (1999). Risk Aversion or Myopia? Choices in Repeated Gambles and Retirement Investments. Management Science, 45(3), 364-â€381. Benartzi, S., & Thaler, R. H. (2007). Heuristics and Biases in Retirement Savings Behavior. Journal Of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), 81-â€104. Beshears, J., Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., Madrian, B. C., & Milkman, K. L. (2011). The Effect of Providing Peer Information on Retirement Savings Decisions. Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., Madrian, B., & Metrick, A. (2005). Optimal Defaults and Active Decisions. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2013). Navigating the Market. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Retrieved from http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201311_cfpb_navigating-â€the-â€market-†final.pdf Fernandes, D., Lynch Jr, J. G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2014). Financial Literacy, Financial Education, and Downstream Financial Behaviors. Management Science. Helman, R. (2014). The 2014 Retirement Confidence Survey: Confidence Rebounds—for Those With Retirement Plans. EBRI Issue Brief, (397). 30 . Ideas42. Financial Heuristics. Ideas42.org. Retrieved from http://www.ideas42.org/financial-â€heuristics/ Kast, Meier, Pomeranz (2012). Under-â€savers anonymous: Evidence on self help groups and peer pressure as a savings commitment device. National Bureau of Economics research. Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2007). Baby boomer retirement security: The roles of planning, financial literacy, and housing wealth. Journal of monetary Economics, 54(1), 205-â€224. Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2009). Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness (No. w14808). National Bureau of Economic Research. Madrian, B. C., & Shea, D. F. (2001). The Power of Suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) Participation and Savings Behavior. Quarterly Journal Of Economics, 116(4), 1149-â€1187. Thaler, R. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing science, 4(3), 199-â€214. 31 .