Description

Investment in the

power sector in

emerging markets

Power generation financing comes with

risks, but finding ways to mitigate these

risks provides opportunities for rewards.

Investment in the power sector in emerging markets

I

. II

White & Case

. Investment in the

power sector in

emerging markets

As the world’s energy dynamic is changing

in response to powerful economic, security

of supply and environmental forces, investment

in and deployment of power infrastructure

is becoming increasingly focused on

emerging markets.

H

owever, infrastructure investment, especially in emerging markets,

can be a risky business. This article aims to identify the main risks that

are particularly pertinent in power projects (with a focus on generation

projects) in emerging markets and then discusses the main ways in which such

risks may be mitigated.

It should be noted that although this article’s focus is on generation, many

of the risks discussed would generally also be applicable to distribution and

transmission assets. In addition, this article does not deal with those risks that

arise in the context of power projects generally, irrespective of whether such

projects are located in an emerging market or otherwise.

This article is divided into three sections:

Â…Â…Part A summarizes some key risks relevant to emerging markets

Kirsti Massie

Partner, White & Case

Project Finance,

Global Head of Power

Ank Santens

Partner, White & Case

International Arbitration

Â…Â…Part B includes a template risk matrix the purpose of which is to identify

emerging market key risks and how such risks may be mitigated

Â…Â…Part C illustrates how international arbitration can be utilized in international

commercial and investment disputes, particularly in emerging markets

Someera Khokhar

Partner, White & Case

Project and Asset Finance

Investment in the power sector in emerging markets

. Power sector in emerging

markets—new opportunities?

In emerging markets, governments and utility companies

(which are often state-owned) have frequently turned

to the Independent Power Producer (IPP) model.

T

he IPP model has proven

successful in attracting new

sources of capital that would

otherwise not have been available

to such markets and ensuring power

projects are constructed efficiently

and quickly. This model also brings

new expertise, skill sets and training

opportunities to such markets.

Typically, new IPPs sell electricity

into the state-dominated power

system under a long-term power

purchase agreement (PPA). A PPA

is entered into between the project

company and the offtaker (again

typically a state-owned entity),

where the offtaker undertakes to

make “availability-based” payments

with smaller payments made for

energy output.

A PPA structure provides a

degree of certainty with respect to

revenues, a certainty that is typically

missing in merchant assets. By

tapping private capital, governments

no longer need to raise the financing

for new capacity themselves—an

attractive option for governments

that are attempting to manage

financial crises and cash-poor state

finances.

From an investor/developer perspective, emerging markets offer the prospect of higher rates of return; however, with such potential rewards come potential risks. PART A: EMERGING MARKETS— KEY RISKS Currency risk Many of the cost components for IPPs such as debt, capital, equipment and fuel are made in a hard currency (e.g., US dollars, pounds sterling or euros), whereas PPA payments, the main source of revenue, are typically (and often times it is a legal requirement that such payments are) made in local currency. This gives rise to currency risk within the project. Currency risk can be subdivided into three main component parts: Â…Â…Exchange rate fluctuations Â…Â…Convertibility risk Â…Â…Repatriation/transfer risk “Exchange rate fluctuation” is the risk of devaluation in a local currency, which is a particular problem where the local currency is not pegged to another harder currency, e.g., US dollars. “Convertibility risk” refers to the risk that insufficient quantities of hard currency will be available to convert the local currency to hard currency—essentially a liquidity risk or some other interference in the ability to convert local currency into hard foreign currency. “Repatriation/transfer risk” refers to the ability to take hard currency out of the local jurisdiction and place it into an offshore account ready for distribution to equity investors and lenders to the project. Revenue risk By “revenue risk” we are referring to circumstances where actual project revenues are less than initially anticipated either through a reduction in the demand for power 2 White & Case emerging markets offer the prospect of higher rates of return; however, with such potential rewards come potential risks. or a reduction in the price payable for the power generated. Over the lifetime of a power project, the demand for the output can diminish due to a number of factors including the construction of additional new generation capacity, which is more efficient or “greener, ” reducing the demand for power from older, less environmentally friendly plants. In addition, an economic downturn may reduce the demand for power generally.

Revenue risk is particularly relevant in the absence of a long-term sales contract such as a PPA or in arrangements where the tariff is not structured on an “availability/capacity” basis, i.e., payments are simply made for the power generated. Additionally, in many emerging markets, the price at which electricity has traditionally been sold does not generally reflect the actual cost of generation, with governments subsidizing power and shielding the ultimate consumer from high power prices. In the event that a government stops providing subsidies or indeed reduces the level of subsidy, the power price will increase and may no longer be affordable to the end user. The issue of government subsidies creates uncertainty, as a government’s commitment to provide subsidies for the duration of the PPA cannot be guaranteed. .

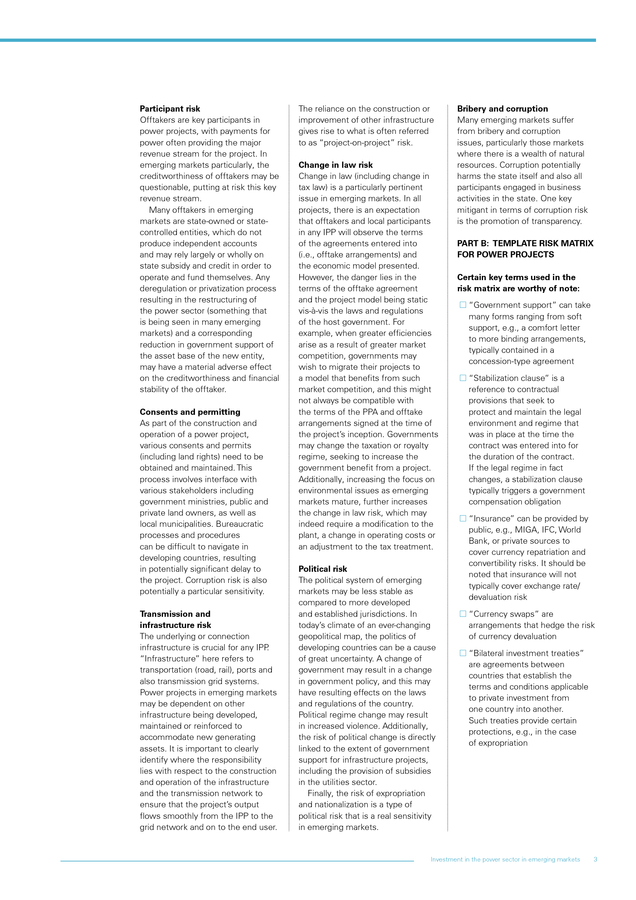

Participant risk Offtakers are key participants in power projects, with payments for power often providing the major revenue stream for the project. In emerging markets particularly, the creditworthiness of offtakers may be questionable, putting at risk this key revenue stream. Many offtakers in emerging markets are state-owned or statecontrolled entities, which do not produce independent accounts and may rely largely or wholly on state subsidy and credit in order to operate and fund themselves. Any deregulation or privatization process resulting in the restructuring of the power sector (something that is being seen in many emerging markets) and a corresponding reduction in government support of the asset base of the new entity, may have a material adverse effect on the creditworthiness and financial stability of the offtaker. Consents and permitting As part of the construction and operation of a power project, various consents and permits (including land rights) need to be obtained and maintained. This process involves interface with various stakeholders including government ministries, public and private land owners, as well as local municipalities.

Bureaucratic processes and procedures can be difficult to navigate in developing countries, resulting in potentially significant delay to the project. Corruption risk is also potentially a particular sensitivity. Transmission and infrastructure risk The underlying or connection infrastructure is crucial for any IPP . “Infrastructure” here refers to transportation (road, rail), ports and also transmission grid systems. Power projects in emerging markets may be dependent on other infrastructure being developed, maintained or reinforced to accommodate new generating assets. It is important to clearly identify where the responsibility lies with respect to the construction and operation of the infrastructure and the transmission network to ensure that the project’s output flows smoothly from the IPP to the grid network and on to the end user. The reliance on the construction or improvement of other infrastructure gives rise to what is often referred to as “project-on-project” risk. Change in law risk Change in law (including change in tax law) is a particularly pertinent issue in emerging markets.

In all projects, there is an expectation that offtakers and local participants in any IPP will observe the terms of the agreements entered into (i.e., offtake arrangements) and the economic model presented. However, the danger lies in the terms of the offtake agreement and the project model being static vis-à-vis the laws and regulations of the host government. For example, when greater efficiencies arise as a result of greater market competition, governments may wish to migrate their projects to a model that benefits from such market competition, and this might not always be compatible with the terms of the PPA and offtake arrangements signed at the time of the project’s inception. Governments may change the taxation or royalty regime, seeking to increase the government benefit from a project. Additionally, increasing the focus on environmental issues as emerging markets mature, further increases the change in law risk, which may indeed require a modification to the plant, a change in operating costs or an adjustment to the tax treatment. Political risk The political system of emerging markets may be less stable as compared to more developed and established jurisdictions.

In today’s climate of an ever-changing geopolitical map, the politics of developing countries can be a cause of great uncertainty. A change of government may result in a change in government policy, and this may have resulting effects on the laws and regulations of the country. Political regime change may result in increased violence. Additionally, the risk of political change is directly linked to the extent of government support for infrastructure projects, including the provision of subsidies in the utilities sector. Finally, the risk of expropriation and nationalization is a type of political risk that is a real sensitivity in emerging markets. Bribery and corruption Many emerging markets suffer from bribery and corruption issues, particularly those markets where there is a wealth of natural resources.

Corruption potentially harms the state itself and also all participants engaged in business activities in the state. One key mitigant in terms of corruption risk is the promotion of transparency. PART B: TEMPLATE RISK MATRIX FOR POWER PROJECTS Certain key terms used in the risk matrix are worthy of note: Â…Â…“Government support” can take many forms ranging from soft support, e.g., a comfort letter to more binding arrangements, typically contained in a concession-type agreement Â…Â…“Stabilization clause” is a reference to contractual provisions that seek to protect and maintain the legal environment and regime that was in place at the time the contract was entered into for the duration of the contract. If the legal regime in fact changes, a stabilization clause typically triggers a government compensation obligation Â…Â…“Insurance” can be provided by public, e.g., MIGA, IFC, World Bank, or private sources to cover currency repatriation and convertibility risks. It should be noted that insurance will not typically cover exchange rate/ devaluation risk Â…Â…“Currency swaps” are arrangements that hedge the risk of currency devaluation Â…Â…“Bilateral investment treaties” are agreements between countries that establish the terms and conditions applicable to private investment from one country into another. Such treaties provide certain protections, e.g., in the case of expropriation Investment in the power sector in emerging markets 3 .

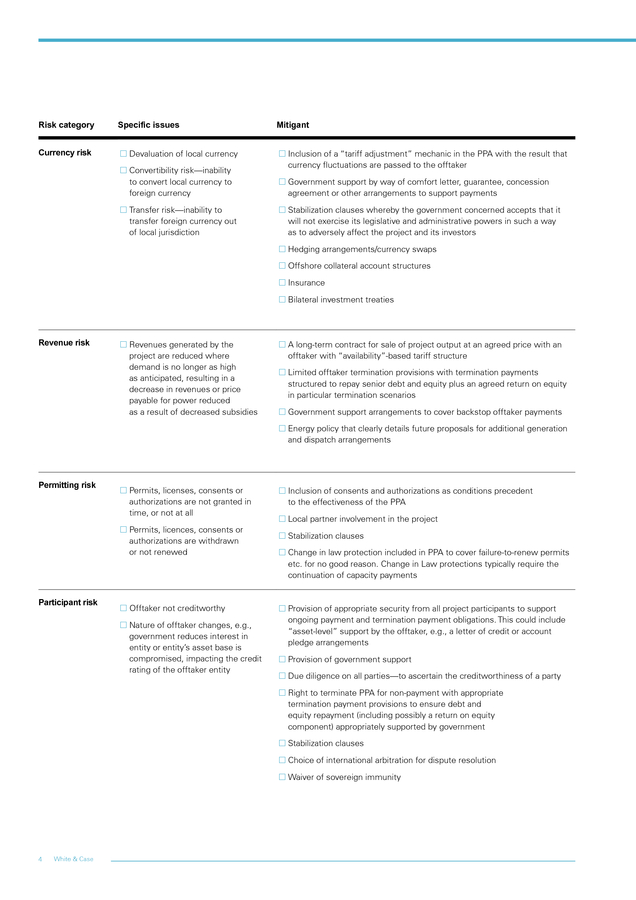

Risk category Specific issues Mitigant Currency risk Â…Â…Devaluation of local currency Â…Â…Inclusion of a “tariff adjustment” mechanic in the PPA with the result that currency fluctuations are passed to the offtaker Â…Â…Convertibility risk—inability to convert local currency to foreign currency Â…Â…Transfer risk—inability to transfer foreign currency out of local jurisdiction Â…Â…Government support by way of comfort letter, guarantee, concession agreement or other arrangements to support payments Â…Â…Stabilization clauses whereby the government concerned accepts that it will not exercise its legislative and administrative powers in such a way as to adversely affect the project and its investors Â…Â…Hedging arrangements/currency swaps Â…Â…Offshore collateral account structures Â…Â…Insurance Â…Â…Bilateral investment treaties Revenue risk Â…Â…Revenues generated by the project are reduced where demand is no longer as high as anticipated, resulting in a decrease in revenues or price payable for power reduced as a result of decreased subsidies Â…Â…A long-term contract for sale of project output at an agreed price with an offtaker with “availability”-based tariff structure Â…Â…Limited offtaker termination provisions with termination payments structured to repay senior debt and equity plus an agreed return on equity in particular termination scenarios Â…Â…Government support arrangements to cover backstop offtaker payments Â…Â…Energy policy that clearly details future proposals for additional generation and dispatch arrangements Permitting risk Â…Â…Permits, licenses, consents or authorizations are not granted in time, or not at all Â…Â…Permits, licences, consents or authorizations are withdrawn or not renewed Participant risk Â…Â…Offtaker not creditworthy Â…Â…Nature of offtaker changes, e.g., government reduces interest in entity or entity’s asset base is compromised, impacting the credit rating of the offtaker entity Â…Â…Inclusion of consents and authorizations as conditions precedent to the effectiveness of the PPA Â…Â…Local partner involvement in the project Â…Â…Stabilization clauses Â…Â…Change in law protection included in PPA to cover failure-to-renew permits etc. for no good reason. Change in Law protections typically require the continuation of capacity payments Â…Â…Provision of appropriate security from all project participants to support ongoing payment and termination payment obligations. This could include “asset-level” support by the offtaker, e.g., a letter of credit or account pledge arrangements Â…Â…Provision of government support Â…Â…Due diligence on all parties—to ascertain the creditworthiness of a party Â…Â…Right to terminate PPA for non-payment with appropriate termination payment provisions to ensure debt and equity repayment (including possibly a return on equity component) appropriately supported by government Â…Â…Stabilization clauses Â…Â…Choice of international arbitration for dispute resolution Â…Â…Waiver of sovereign immunity 4 White & Case .

Risk category Specific issues Mitigant Infrastructure risk Â…Â…Inadequate or non-existent infrastructure requires construction of new or enhanced infrastructure Â…Â…Inclusion of “executed project documents” as conditions precedent to the effectiveness of the PPA Â…Â…Delay in/non-availability of the site and delays in the completion of the purchase or lease arrangements Â…Â…Structure such that responsibility for building accompanying infrastructure falls on the project company with a subsequent transfer to a government entity’s pre-commissioning of the plant. This will depend on the nature of the infrastructure required and the skill set and resources of the project company and sponsors Â…Â…Liquidated damages and/or compensation for any delay to plant commissioning as a result of inadequate or incomplete infrastructure, where responsibility for infrastructure lies outside of the project company Â…Â…Host government to provide guarantees and support to ensure that infrastructure is built on time and according to the required specifications Change in law risk Â…Â…Government enactment of new legislation that adversely affects investment returns or the viability of the project, or the equity investors’ participation in the project Â…Â…Any change in law should result in appropriate tariff adjustment to reflect any consequential cost increases arising directly as a result of a change in law Â…Â…Stabilization clause Â…Â…Political risk insurance Â…Â…Bilateral investment treaty protection Â…Â…Waiver of sovereign immunity Â…Â…Involvement of IFIs may reduce risk of changes in law designed to adversely affect foreign investors Â…Â…Host government to provide guarantees and support to ensure that infrastructure is built on time and according to the required specifications Country/ political risk Â…Â…High crime rate Â…Â…Bilateral investment treaty protection Â…Â…Future country development that may lead to aggressive policies or expropriation Â…Â…Political risk insurance Â…Â…Arbitrary cancellation of government licenses and concessions Â…Â…Stabilization clause Â…Â…International arbitration Â…Â…Government support Â…Â…Involvement of IFIs Corruption risk Â…Â…Bribery or corruption risk with respect to project Â…Â…Transparency Â…Â…Involvement of IFIs Â…Â…Investor to have in place robust internal systems Investment in the power sector in emerging markets 5 . PART C: IMPORTANCE OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION AND BILATERAL INVESTMENT TREATIES IN EMERGING MARKETS International arbitration for resolving international disputes International arbitration is a binding form of alternative dispute resolution and the preferred method for resolving international commercial and investment disputes, particularly in emerging markets. Parties often perceive international arbitration to be more neutral than litigation due to the concern that local courts may favor local companies or the host state, especially in developing states where often the rule of law is weak. In addition, in international arbitration, the parties generally are the ones who select the arbitrators, which enables them to choose decision-makers whose judgment they trust and who have the relevant expertise, such as language capabilities, legal background, and subject-matter knowledge. International arbitration also is generally private, and the parties can agree to make it confidential. Privacy means that only the parties may participate in the proceedings, attend the hearings and receive the award, while confidentiality imposes an obligation on the parties not to disclose information concerning the proceedings to third parties. Unlike litigation, international arbitration is not subject to appeal. While it is possible for a court at the “seat of arbitration, i.e., the ” legal place of arbitration, to set aside an arbitral award, the grounds for doing so are limited and the threshold is high, particularly in arbitration-friendly jurisdictions, such as England, France, Switzerland and the United States. Parties tend to pay adverse arbitral awards voluntarily, but, if they refuse to do so, the prevailing party may initiate enforcement proceedings in domestic courts throughout the world.

Under the New York Convention, 156 states have agreed to recognize and enforce foreign arbitral awards, subject to certain limited exceptions. 6 White & Case International investment agreements Because international arbitration is based on party consent, the parties must have agreed to arbitrate through, for example, an arbitration clause in a contract or a concession agreement. An investor also may be able to arbitrate against a host state based upon an arbitration clause in an international investment agreement. International investment agreements are agreements between two or more states for the promotion and protection of foreign investment. In these agreements, the state agrees to protect certain investments and investors of the other state.

The protected “investment” generally is broadly defined to include, among other things, shares, licenses, contracts, concession agreements and liens. The substantive protections offered by such agreements generally include protections against unlawful expropriation, unfair and inequitable treatment, and arbitrary and unreasonable treatment. International investment agreements exist in three primary forms: (1) bilateral investment treaties (BITs); (2) multilateral investment treaties (MITs); and (3) free trade agreements (FTAs). The most common international investment agreement is the BIT, which is an investment promotion and protection treaty concluded between two states. Most states have signed BITs, and approximately 3,000 BITs in total are in force today. The United States, for example, has concluded 40 BITs; India has concluded nearly 70 BITs; and China has concluded more than 100 BITs. A notable exception is Brazil, which currently has no BITs in force. MITs are international investment agreements between more than two states. One example is the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT).

Nearly 50 European and former Soviet states have agreed in the ECT to arbitrate disputes with foreign investors relating to investments in the energy sector. Other MITs include the 1987 ASEAN Agreement for the Promotion and Protection of Investments between six states in Southeast Asia, and the Investment Agreement for the COMESA Common Investment Area between states in Eastern and Southern Africa. FTAs are international trade agreements between two or more states, which often contain investment chapters with arbitration provisions similar to those in many BITs and MITs.

Two notable examples of FTAs with investment chapters are the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the United States, Canada and Mexico, and the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) between the United States and six Central American states. 3,000 BITs approximately, are in force today 40 BITs concluded in the United States 70 BITs concluded in India 100+ BITs concluded in China Strategic considerations In drafting an arbitration clause to be included in a contract or concession agreement, the three most fundamental issues that the investor will need to consider are: (1) the applicable arbitration rules; (2) the seat of the arbitration; and (3) the governing law. Investors also need to consider their corporate nationality and whether they qualify for protection under one or more international investment agreements. In choosing the applicable arbitration rules, parties have many choices. One important choice is between institutional arbitration (where an administrative body administers the arbitration) and ad hoc arbitration (where there is no administrative body).

While ad hoc arbitration can work well, administered arbitration is generally recommended in relation to power projects in emerging markets, where there is a risk that the local party may not cooperate in the arbitration, and the arbitral institution can help move the process along. One prominent institution for resolving international investment disputes is the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), which is the arbitration arm of The World Bank based in Washington, DC and established under the ICSID Convention, a multilateral treaty ratified by 151 states. The International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) in Paris, France is one of the world’s leading institutions for administering international commercial arbitrations. The 2010 International Arbitration Survey by White & Case llp and .

Private equity firms that have invested in emerging markets have been able to benefit from international arbitration, particularly international investment arbitration. Queen Mary College—which was based on a questionnaire completed by 136 corporate counsel and interviews of 67 corporate counsel— reported that the ICC is the most preferred and widely used arbitration institution. The same survey reported that the second most preferred arbitration institution was the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), which is based in London, England. Other prominent institutions include the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC), the American Arbitration Association’s International Centre for Dispute Resolution (ICDR), the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC) and the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC). Finally, some parties —including many states—choose ad hoc arbitration pursuant to the Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). In drafting an arbitration clause, an investor also must choose the seat of arbitration. The seat is critical, as it will determine which and to what extent domestic courts may support or interfere with the arbitration.

If there is concern that the courts of the host state may not be neutral or may be hostile to arbitration, it is critical that the arbitration be seated in a different jurisdiction. There are several examples where an investor in an emerging country was successful in international arbitration only to see the host state or local party obstruct the result through its local courts. While the investor might be able to salvage the arbitral award through recognition and enforcement in a different country, this is usually a lengthy process with an uncertain outcome; the better method to guard against this risk is to seat the arbitration offshore. (Note that the seat plays a less significant role in ICSID arbitrations, which are self-contained and operate outside the realm of domestic courts.) Investors also must consider which law will govern their contract or concession agreement.

Usually, there is no choice, and the law of the host state will govern. In addition to the terms of the arbitration clause, an investor also should be mindful of its corporate nationality. As mentioned above, international investment agreements protect only certain “investments” of certain “investors.

Before any ” dispute arises, the investor thus must structure its investment so as to ensure that it will benefit from the protections of at least one international investment agreement. Experience of private equity firms in international investment arbitration Private equity firms that have invested in emerging markets have been able to benefit from international arbitration, particularly international investment arbitration. In AIG Capital Partners Inc. v.

Kazakhstan, for example, Kazakhstan’s political subdivisions expropriated an AIG private equity fund’s investments in a real estate development project. The claimants commenced ICSID arbitration pursuant to the US-Kazakhstan BIT, and the ICSID tribunal awarded the claimants US$9.9 million. In Rurelec v.

Bolivia, Bolivia similarly expropriated a British company’s private equity investment in a power generation company. The claimants commenced an ad hoc arbitration pursuant to the US-Bolivia BIT and UK-Bolivia BIT, and the tribunal ultimately awarded the claimant US$35.5 million. n Investment in the power sector in emerging markets 7 .

EMEA Kirsti Massie Partner, London T +44 20 7532 2314 E kmassie@whitecase.com Americas Ank Santens Partner, New York T +1 212 819 8599 E asantens@whitecase.com Someera Khokhar Partner, New York T +1 212 819 8846 E skhokhar@whitecase.com White & Case NY0915/TL/B/153550_M2 8 . © ML Sinibaldi/CORBIS . In this publication, White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case llp, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case llp, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities. This publication is prepared for the general information of our clients and other interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice. © 2015 White & Case llp X White & Case .

From an investor/developer perspective, emerging markets offer the prospect of higher rates of return; however, with such potential rewards come potential risks. PART A: EMERGING MARKETS— KEY RISKS Currency risk Many of the cost components for IPPs such as debt, capital, equipment and fuel are made in a hard currency (e.g., US dollars, pounds sterling or euros), whereas PPA payments, the main source of revenue, are typically (and often times it is a legal requirement that such payments are) made in local currency. This gives rise to currency risk within the project. Currency risk can be subdivided into three main component parts: Â…Â…Exchange rate fluctuations Â…Â…Convertibility risk Â…Â…Repatriation/transfer risk “Exchange rate fluctuation” is the risk of devaluation in a local currency, which is a particular problem where the local currency is not pegged to another harder currency, e.g., US dollars. “Convertibility risk” refers to the risk that insufficient quantities of hard currency will be available to convert the local currency to hard currency—essentially a liquidity risk or some other interference in the ability to convert local currency into hard foreign currency. “Repatriation/transfer risk” refers to the ability to take hard currency out of the local jurisdiction and place it into an offshore account ready for distribution to equity investors and lenders to the project. Revenue risk By “revenue risk” we are referring to circumstances where actual project revenues are less than initially anticipated either through a reduction in the demand for power 2 White & Case emerging markets offer the prospect of higher rates of return; however, with such potential rewards come potential risks. or a reduction in the price payable for the power generated. Over the lifetime of a power project, the demand for the output can diminish due to a number of factors including the construction of additional new generation capacity, which is more efficient or “greener, ” reducing the demand for power from older, less environmentally friendly plants. In addition, an economic downturn may reduce the demand for power generally.

Revenue risk is particularly relevant in the absence of a long-term sales contract such as a PPA or in arrangements where the tariff is not structured on an “availability/capacity” basis, i.e., payments are simply made for the power generated. Additionally, in many emerging markets, the price at which electricity has traditionally been sold does not generally reflect the actual cost of generation, with governments subsidizing power and shielding the ultimate consumer from high power prices. In the event that a government stops providing subsidies or indeed reduces the level of subsidy, the power price will increase and may no longer be affordable to the end user. The issue of government subsidies creates uncertainty, as a government’s commitment to provide subsidies for the duration of the PPA cannot be guaranteed. .

Participant risk Offtakers are key participants in power projects, with payments for power often providing the major revenue stream for the project. In emerging markets particularly, the creditworthiness of offtakers may be questionable, putting at risk this key revenue stream. Many offtakers in emerging markets are state-owned or statecontrolled entities, which do not produce independent accounts and may rely largely or wholly on state subsidy and credit in order to operate and fund themselves. Any deregulation or privatization process resulting in the restructuring of the power sector (something that is being seen in many emerging markets) and a corresponding reduction in government support of the asset base of the new entity, may have a material adverse effect on the creditworthiness and financial stability of the offtaker. Consents and permitting As part of the construction and operation of a power project, various consents and permits (including land rights) need to be obtained and maintained. This process involves interface with various stakeholders including government ministries, public and private land owners, as well as local municipalities.

Bureaucratic processes and procedures can be difficult to navigate in developing countries, resulting in potentially significant delay to the project. Corruption risk is also potentially a particular sensitivity. Transmission and infrastructure risk The underlying or connection infrastructure is crucial for any IPP . “Infrastructure” here refers to transportation (road, rail), ports and also transmission grid systems. Power projects in emerging markets may be dependent on other infrastructure being developed, maintained or reinforced to accommodate new generating assets. It is important to clearly identify where the responsibility lies with respect to the construction and operation of the infrastructure and the transmission network to ensure that the project’s output flows smoothly from the IPP to the grid network and on to the end user. The reliance on the construction or improvement of other infrastructure gives rise to what is often referred to as “project-on-project” risk. Change in law risk Change in law (including change in tax law) is a particularly pertinent issue in emerging markets.

In all projects, there is an expectation that offtakers and local participants in any IPP will observe the terms of the agreements entered into (i.e., offtake arrangements) and the economic model presented. However, the danger lies in the terms of the offtake agreement and the project model being static vis-à-vis the laws and regulations of the host government. For example, when greater efficiencies arise as a result of greater market competition, governments may wish to migrate their projects to a model that benefits from such market competition, and this might not always be compatible with the terms of the PPA and offtake arrangements signed at the time of the project’s inception. Governments may change the taxation or royalty regime, seeking to increase the government benefit from a project. Additionally, increasing the focus on environmental issues as emerging markets mature, further increases the change in law risk, which may indeed require a modification to the plant, a change in operating costs or an adjustment to the tax treatment. Political risk The political system of emerging markets may be less stable as compared to more developed and established jurisdictions.

In today’s climate of an ever-changing geopolitical map, the politics of developing countries can be a cause of great uncertainty. A change of government may result in a change in government policy, and this may have resulting effects on the laws and regulations of the country. Political regime change may result in increased violence. Additionally, the risk of political change is directly linked to the extent of government support for infrastructure projects, including the provision of subsidies in the utilities sector. Finally, the risk of expropriation and nationalization is a type of political risk that is a real sensitivity in emerging markets. Bribery and corruption Many emerging markets suffer from bribery and corruption issues, particularly those markets where there is a wealth of natural resources.

Corruption potentially harms the state itself and also all participants engaged in business activities in the state. One key mitigant in terms of corruption risk is the promotion of transparency. PART B: TEMPLATE RISK MATRIX FOR POWER PROJECTS Certain key terms used in the risk matrix are worthy of note: Â…Â…“Government support” can take many forms ranging from soft support, e.g., a comfort letter to more binding arrangements, typically contained in a concession-type agreement Â…Â…“Stabilization clause” is a reference to contractual provisions that seek to protect and maintain the legal environment and regime that was in place at the time the contract was entered into for the duration of the contract. If the legal regime in fact changes, a stabilization clause typically triggers a government compensation obligation Â…Â…“Insurance” can be provided by public, e.g., MIGA, IFC, World Bank, or private sources to cover currency repatriation and convertibility risks. It should be noted that insurance will not typically cover exchange rate/ devaluation risk Â…Â…“Currency swaps” are arrangements that hedge the risk of currency devaluation Â…Â…“Bilateral investment treaties” are agreements between countries that establish the terms and conditions applicable to private investment from one country into another. Such treaties provide certain protections, e.g., in the case of expropriation Investment in the power sector in emerging markets 3 .

Risk category Specific issues Mitigant Currency risk Â…Â…Devaluation of local currency Â…Â…Inclusion of a “tariff adjustment” mechanic in the PPA with the result that currency fluctuations are passed to the offtaker Â…Â…Convertibility risk—inability to convert local currency to foreign currency Â…Â…Transfer risk—inability to transfer foreign currency out of local jurisdiction Â…Â…Government support by way of comfort letter, guarantee, concession agreement or other arrangements to support payments Â…Â…Stabilization clauses whereby the government concerned accepts that it will not exercise its legislative and administrative powers in such a way as to adversely affect the project and its investors Â…Â…Hedging arrangements/currency swaps Â…Â…Offshore collateral account structures Â…Â…Insurance Â…Â…Bilateral investment treaties Revenue risk Â…Â…Revenues generated by the project are reduced where demand is no longer as high as anticipated, resulting in a decrease in revenues or price payable for power reduced as a result of decreased subsidies Â…Â…A long-term contract for sale of project output at an agreed price with an offtaker with “availability”-based tariff structure Â…Â…Limited offtaker termination provisions with termination payments structured to repay senior debt and equity plus an agreed return on equity in particular termination scenarios Â…Â…Government support arrangements to cover backstop offtaker payments Â…Â…Energy policy that clearly details future proposals for additional generation and dispatch arrangements Permitting risk Â…Â…Permits, licenses, consents or authorizations are not granted in time, or not at all Â…Â…Permits, licences, consents or authorizations are withdrawn or not renewed Participant risk Â…Â…Offtaker not creditworthy Â…Â…Nature of offtaker changes, e.g., government reduces interest in entity or entity’s asset base is compromised, impacting the credit rating of the offtaker entity Â…Â…Inclusion of consents and authorizations as conditions precedent to the effectiveness of the PPA Â…Â…Local partner involvement in the project Â…Â…Stabilization clauses Â…Â…Change in law protection included in PPA to cover failure-to-renew permits etc. for no good reason. Change in Law protections typically require the continuation of capacity payments Â…Â…Provision of appropriate security from all project participants to support ongoing payment and termination payment obligations. This could include “asset-level” support by the offtaker, e.g., a letter of credit or account pledge arrangements Â…Â…Provision of government support Â…Â…Due diligence on all parties—to ascertain the creditworthiness of a party Â…Â…Right to terminate PPA for non-payment with appropriate termination payment provisions to ensure debt and equity repayment (including possibly a return on equity component) appropriately supported by government Â…Â…Stabilization clauses Â…Â…Choice of international arbitration for dispute resolution Â…Â…Waiver of sovereign immunity 4 White & Case .

Risk category Specific issues Mitigant Infrastructure risk Â…Â…Inadequate or non-existent infrastructure requires construction of new or enhanced infrastructure Â…Â…Inclusion of “executed project documents” as conditions precedent to the effectiveness of the PPA Â…Â…Delay in/non-availability of the site and delays in the completion of the purchase or lease arrangements Â…Â…Structure such that responsibility for building accompanying infrastructure falls on the project company with a subsequent transfer to a government entity’s pre-commissioning of the plant. This will depend on the nature of the infrastructure required and the skill set and resources of the project company and sponsors Â…Â…Liquidated damages and/or compensation for any delay to plant commissioning as a result of inadequate or incomplete infrastructure, where responsibility for infrastructure lies outside of the project company Â…Â…Host government to provide guarantees and support to ensure that infrastructure is built on time and according to the required specifications Change in law risk Â…Â…Government enactment of new legislation that adversely affects investment returns or the viability of the project, or the equity investors’ participation in the project Â…Â…Any change in law should result in appropriate tariff adjustment to reflect any consequential cost increases arising directly as a result of a change in law Â…Â…Stabilization clause Â…Â…Political risk insurance Â…Â…Bilateral investment treaty protection Â…Â…Waiver of sovereign immunity Â…Â…Involvement of IFIs may reduce risk of changes in law designed to adversely affect foreign investors Â…Â…Host government to provide guarantees and support to ensure that infrastructure is built on time and according to the required specifications Country/ political risk Â…Â…High crime rate Â…Â…Bilateral investment treaty protection Â…Â…Future country development that may lead to aggressive policies or expropriation Â…Â…Political risk insurance Â…Â…Arbitrary cancellation of government licenses and concessions Â…Â…Stabilization clause Â…Â…International arbitration Â…Â…Government support Â…Â…Involvement of IFIs Corruption risk Â…Â…Bribery or corruption risk with respect to project Â…Â…Transparency Â…Â…Involvement of IFIs Â…Â…Investor to have in place robust internal systems Investment in the power sector in emerging markets 5 . PART C: IMPORTANCE OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION AND BILATERAL INVESTMENT TREATIES IN EMERGING MARKETS International arbitration for resolving international disputes International arbitration is a binding form of alternative dispute resolution and the preferred method for resolving international commercial and investment disputes, particularly in emerging markets. Parties often perceive international arbitration to be more neutral than litigation due to the concern that local courts may favor local companies or the host state, especially in developing states where often the rule of law is weak. In addition, in international arbitration, the parties generally are the ones who select the arbitrators, which enables them to choose decision-makers whose judgment they trust and who have the relevant expertise, such as language capabilities, legal background, and subject-matter knowledge. International arbitration also is generally private, and the parties can agree to make it confidential. Privacy means that only the parties may participate in the proceedings, attend the hearings and receive the award, while confidentiality imposes an obligation on the parties not to disclose information concerning the proceedings to third parties. Unlike litigation, international arbitration is not subject to appeal. While it is possible for a court at the “seat of arbitration, i.e., the ” legal place of arbitration, to set aside an arbitral award, the grounds for doing so are limited and the threshold is high, particularly in arbitration-friendly jurisdictions, such as England, France, Switzerland and the United States. Parties tend to pay adverse arbitral awards voluntarily, but, if they refuse to do so, the prevailing party may initiate enforcement proceedings in domestic courts throughout the world.

Under the New York Convention, 156 states have agreed to recognize and enforce foreign arbitral awards, subject to certain limited exceptions. 6 White & Case International investment agreements Because international arbitration is based on party consent, the parties must have agreed to arbitrate through, for example, an arbitration clause in a contract or a concession agreement. An investor also may be able to arbitrate against a host state based upon an arbitration clause in an international investment agreement. International investment agreements are agreements between two or more states for the promotion and protection of foreign investment. In these agreements, the state agrees to protect certain investments and investors of the other state.

The protected “investment” generally is broadly defined to include, among other things, shares, licenses, contracts, concession agreements and liens. The substantive protections offered by such agreements generally include protections against unlawful expropriation, unfair and inequitable treatment, and arbitrary and unreasonable treatment. International investment agreements exist in three primary forms: (1) bilateral investment treaties (BITs); (2) multilateral investment treaties (MITs); and (3) free trade agreements (FTAs). The most common international investment agreement is the BIT, which is an investment promotion and protection treaty concluded between two states. Most states have signed BITs, and approximately 3,000 BITs in total are in force today. The United States, for example, has concluded 40 BITs; India has concluded nearly 70 BITs; and China has concluded more than 100 BITs. A notable exception is Brazil, which currently has no BITs in force. MITs are international investment agreements between more than two states. One example is the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT).

Nearly 50 European and former Soviet states have agreed in the ECT to arbitrate disputes with foreign investors relating to investments in the energy sector. Other MITs include the 1987 ASEAN Agreement for the Promotion and Protection of Investments between six states in Southeast Asia, and the Investment Agreement for the COMESA Common Investment Area between states in Eastern and Southern Africa. FTAs are international trade agreements between two or more states, which often contain investment chapters with arbitration provisions similar to those in many BITs and MITs.

Two notable examples of FTAs with investment chapters are the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the United States, Canada and Mexico, and the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) between the United States and six Central American states. 3,000 BITs approximately, are in force today 40 BITs concluded in the United States 70 BITs concluded in India 100+ BITs concluded in China Strategic considerations In drafting an arbitration clause to be included in a contract or concession agreement, the three most fundamental issues that the investor will need to consider are: (1) the applicable arbitration rules; (2) the seat of the arbitration; and (3) the governing law. Investors also need to consider their corporate nationality and whether they qualify for protection under one or more international investment agreements. In choosing the applicable arbitration rules, parties have many choices. One important choice is between institutional arbitration (where an administrative body administers the arbitration) and ad hoc arbitration (where there is no administrative body).

While ad hoc arbitration can work well, administered arbitration is generally recommended in relation to power projects in emerging markets, where there is a risk that the local party may not cooperate in the arbitration, and the arbitral institution can help move the process along. One prominent institution for resolving international investment disputes is the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), which is the arbitration arm of The World Bank based in Washington, DC and established under the ICSID Convention, a multilateral treaty ratified by 151 states. The International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) in Paris, France is one of the world’s leading institutions for administering international commercial arbitrations. The 2010 International Arbitration Survey by White & Case llp and .

Private equity firms that have invested in emerging markets have been able to benefit from international arbitration, particularly international investment arbitration. Queen Mary College—which was based on a questionnaire completed by 136 corporate counsel and interviews of 67 corporate counsel— reported that the ICC is the most preferred and widely used arbitration institution. The same survey reported that the second most preferred arbitration institution was the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), which is based in London, England. Other prominent institutions include the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC), the American Arbitration Association’s International Centre for Dispute Resolution (ICDR), the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC) and the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC). Finally, some parties —including many states—choose ad hoc arbitration pursuant to the Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). In drafting an arbitration clause, an investor also must choose the seat of arbitration. The seat is critical, as it will determine which and to what extent domestic courts may support or interfere with the arbitration.

If there is concern that the courts of the host state may not be neutral or may be hostile to arbitration, it is critical that the arbitration be seated in a different jurisdiction. There are several examples where an investor in an emerging country was successful in international arbitration only to see the host state or local party obstruct the result through its local courts. While the investor might be able to salvage the arbitral award through recognition and enforcement in a different country, this is usually a lengthy process with an uncertain outcome; the better method to guard against this risk is to seat the arbitration offshore. (Note that the seat plays a less significant role in ICSID arbitrations, which are self-contained and operate outside the realm of domestic courts.) Investors also must consider which law will govern their contract or concession agreement.

Usually, there is no choice, and the law of the host state will govern. In addition to the terms of the arbitration clause, an investor also should be mindful of its corporate nationality. As mentioned above, international investment agreements protect only certain “investments” of certain “investors.

Before any ” dispute arises, the investor thus must structure its investment so as to ensure that it will benefit from the protections of at least one international investment agreement. Experience of private equity firms in international investment arbitration Private equity firms that have invested in emerging markets have been able to benefit from international arbitration, particularly international investment arbitration. In AIG Capital Partners Inc. v.

Kazakhstan, for example, Kazakhstan’s political subdivisions expropriated an AIG private equity fund’s investments in a real estate development project. The claimants commenced ICSID arbitration pursuant to the US-Kazakhstan BIT, and the ICSID tribunal awarded the claimants US$9.9 million. In Rurelec v.

Bolivia, Bolivia similarly expropriated a British company’s private equity investment in a power generation company. The claimants commenced an ad hoc arbitration pursuant to the US-Bolivia BIT and UK-Bolivia BIT, and the tribunal ultimately awarded the claimant US$35.5 million. n Investment in the power sector in emerging markets 7 .

EMEA Kirsti Massie Partner, London T +44 20 7532 2314 E kmassie@whitecase.com Americas Ank Santens Partner, New York T +1 212 819 8599 E asantens@whitecase.com Someera Khokhar Partner, New York T +1 212 819 8846 E skhokhar@whitecase.com White & Case NY0915/TL/B/153550_M2 8 . © ML Sinibaldi/CORBIS . In this publication, White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case llp, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case llp, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities. This publication is prepared for the general information of our clients and other interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice. © 2015 White & Case llp X White & Case .