What’s New for the 2016 Proxy Season: Engagement, Transparency, Proxy Access and More - January 26, 2016

Weil, Gotshal & Manges

Description

January 26, 2016

What’s New for the

2016 Proxy Season

Engagement,

Transparency,

Proxy Access

and More

While shareholders have a wide spectrum of views on corporate

objectives, the time horizon for realizing these objectives and

environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues, there is an emerging

consensus that – regardless of size, industry or profitability– public

companies must achieve greater accountability to their shareholders,

through engagement and transparency, than ever before. Corporate

engagement and transparency now take two forms: direct dialogue,

increasingly involving directors, and enhanced proxy statement and other

public disclosure that sheds light on the company’s strategy and the

performance of its board, board committees and management,

demonstrates responsiveness to shareholder ESG concerns, and justifies

the composition of the board in light of the company’s present needs.

Throughout this Alert, we offer practical suggestions about “what to do

now” to meet shareholder expectations about engagement and

transparency and to address a host of other new developments for the

2016 proxy season.

Preparing for the 2016 Proxy Season

1. Achieving Greater Engagement and Transparency

2. Understanding the Spectrum of Shareholder Views

3.

Keeping Up with Fast-Moving Proxy Access Developments 4. Anticipating Other Shareholder Proposals 5. Considering the Impact of ISS and Glass Lewis Voting Policy Updates 6.

Key Issues for the Nom/Gov Committee: Director Tenure, Independence, Gender Diversity and Skills 7. Another Key Issue for the Nom/Gov Committee or Full Board: Sustainability 8. Key Governance Issues for the Audit Committee: Overload, Composition and Reporting 9.

Key Issues for the Compensation Committee: The Dodd-Frank Final Four and Director Compensation 10. Developments in Litigation-Related Bylaws: Exclusive Forum and Fee Shifting Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance 1. Achieving Greater Engagement and Transparency The paradigm of a company’s senior management, investor relations team and/or corporate secretary serving as the only points of contact for shareholders, with communications limited to regularly scheduled meetings, conference calls or investor days, or discussions with analysts and portfolio managers at only a few major institutional investors, is fast becoming a relic of the past. Recent high profile proxy fights and activist attacks, the continuing influence of proxy advisory firms, the power and growing advocacy of institutional investors, the SEC’s continuing attention to the relationship between directors and shareholders, 1 the impact of social media and the public’s wavering confidence in corporations have combined to highlight the need for effective communication throughout the year. BlackRock Chairman and CEO Laurence D. Fink urged this approach in an April 2015 letter to the CEOs of the S&P 500 and the largest companies around the world in which BlackRock invests, calling for “consistent and sustained” engagement – not just during proxy season or at the time of earnings reports.

2 Some companies are heeding this call and publicly disclosing their programs. Many of these companies are encouraging shareholders to communicate with them at any time of the year through online feedback forms, creating annual engagement calendars, and scheduling regular meetings with their shareholders to hear their concerns and provide meaningful information about the company. 3 Other companies are expressly assigning engagement efforts to existing board committees, such as the nominating and governance committee or, as suggested by Vanguard, to new committees with a sole focus on engagement (e.g., Tempur Sealy International, Inc.’s Stockholder Liaison Committee 4).

Companies such as Allstate, Coca-Cola, EMC, PepsiCo and Prudential Financial have been noted as providing informative disclosure about their engagement programs. 5 Engagement is not just an issue for large corporations; smaller companies are also facing shareholder pressure to engage. Since 2011, The California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) has been targeting and engaging with Russell 2000 companies on majority voting, with an increasing number of companies adopting majority voting in response to a CalSTRS’ letter sent in advance of the submission of a shareholder proposal.

6 Should Directors Engage? From their vantage point as long-term equity holders of nearly every publicly traded company in the U.S., institutional investors and large asset managers such as BlackRock and Vanguard have advocated that engagement – at least with investors such as themselves – should consist not only of interactions with management but also with the company’s lead director or other independent members of the board. In a February 2015 letter to the independent board leaders of 500 of its funds’ largest U.S. holdings, Vanguard Chairman and CEO F.

William McNabb III encouraged enhanced discussion between directors and shareholders, emphasizing that boards that do this are “more likely to have stronger support of large long-term shareholders.” 7 Vanguard’s update on its proxy voting and engagement efforts for the 12 months ended June 30, 2015 described the goal of these efforts as providing “constructive input that will better position companies to deliver sustainable value over the long term for all investors.” 8 While some boards remain hesitant, proponents of board engagement argue that it can help a board hear directly what shareholders are saying, articulate directly to shareholders the board’s commitment to long-term strategy and, in the final analysis, establish a level of confidence in the integrity and independence of the board’s stewardship that may help the company weather a future storm. Transparency goes hand-in-hand with engagement. Just as there is no one mode of engagement, there is no one topic as to which greater transparency will satisfy the expectations of all investors all of the time. Different investors may seek enhanced disclosure regarding the company’s business strategy, capital allocation plans, risk tolerance and management, board composition and refreshment, executive compensation, the impact of climate change on short- and long-term corporate performance, or a myriad of other ESG concerns.

There are also a variety of vehicles for dissemination of these disclosures. To illustrate, some shareholders want to see social and environmental (sustainability) performance metrics applied and included in periodic reports (primarily the Form 10-K), while others are content with enhanced supplemental disclosure in the form of web-posted sustainability reports. Throughout this Alert, we offer suggestions for increasing transparency about ESG matters.

See Parts 5,6,7,8 and 9 below. Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 2 . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance As investors continue to make their case for engagement, the SEC Staff has made it clear that Regulation FD’s ban on selective disclosure of material, non-public company information should not impede constructive engagement between directors and shareholders if desired by all concerned. 9 We provide some guidance in this respect immediately below. What To Do Now: â— Design and Update Shareholder Outreach Programs. More and more companies are developing and disclosing formal shareholder engagement programs that extend throughout the year, not only in anticipation of proxy season. In developing such a program, a company should consider its governance profile and potential vulnerabilities, its shareholder base, and its most effective management and board participants.

Engagement efforts should be individually tailored to what is of most importance to a specific shareholder. The engagement strategy should be assessed and updated periodically to reflect evolving practice and changes in the company’s circumstances. â— Use Your Proxy Statement as a Communications Tool—Including about Outreach Itself. A key opportunity for effective engagement is to use the upcoming proxy statement to put the company’s best foot forward on governance.

The proxy statement should clearly and concisely discuss matters that shareholders consider important in formulating voting decisions, including the qualifications of the board’s nominees, board refreshment policies, oversight activities and the link between corporate performance and executive compensation. This year, if the company has not done so previously, consider highlighting the nature and results of shareholder outreach, including the number of times it took place during the year, who participated on behalf of the company, the total percentage of shares represented at these discussions, a general indication of the topics discussed, how shareholder feedback was conveyed to the board and taken into account (including, importantly, any changes in governance made in response to the feedback) and the channels of communication open to shareholders for engagement in the future. Proxy statement innovations such as the use of charts, figures and images help companies bring to life the story of the company’s management, oversight, compensation practices, business practices and shareholder engagement. â— Understand Your Shareholder Base and the Positions of Shareholders.

It is critical for companies to understand the sometimes distinct positions of pension funds and other institutional investors on various governance issues. Not every institution follows the position of ISS or Glass Lewis on every issue. In addition, outreach to retail investors (who tend to vote at lower levels and to be less concerned with governance issues than institutions) should not be overlooked. â— Ensure Information Flow to the Board.

Particularly where directors do not participate directly in shareholder outreach, it is essential that the board regularly obtain information on any concerns expressed by major shareholders during the company’s outreach efforts. A process should be in place to facilitate and organize an unfiltered flow of information from shareholders to directors, giving the board a more direct understanding of how shareholders have responded, or are likely to respond, to their decision-making. â— Engage with the Appropriate Contacts at Shareholders. Ensure that the person with whom the company is engaging on governance issues is the most appropriate contact to address these issues.

The decision-making roles at institutions often are split between voting and investment. â— Select and Prepare Directors who will Communicate with Shareholders. When director involvement is desirable, give thought to selecting the particular director or directors who will communicate with particular shareholders. In some cases, the selection will reflect position (e.g., independent chair or lead independent director); in others, relevant expertise to address the shareholder’s key concern (e.g., chair of the compensation or nominating/corporate governance committee).

Once identified, these directors should be briefed on the “dos and don’ts” of meeting with shareholders, including Regulation FD. Directors should be cautioned not to “go it alone” and instead to include in the discussion at least one other company representative, such as inside or outside counsel or someone from investor relations, human resources or finance. 10 Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 3 .

SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance â— Consider Regulation FD and Proxy Rules. Be mindful of Regulation FD, but do not use it as a shield or barrier to director-shareholder communication if you otherwise decide that such communication is in the company’s best interests. For those companies that opt to authorize one or more directors to meet with shareholders, the SEC Staff recommends consideration of “implementing policies and procedures intended to help avoid Regulation FD violations, such as pre-clearing discussion topics with the shareholder or having company counsel attend the meeting.” 11 To give their directors and/or other representatives ample FD protection when meeting with shareholders, whether in person or by telephone or videoconference, companies should provide full and fair disclosure of their key governance practices and any pertinent corporate performance metrics in their proxy statements and/or periodic reports. 12 (In this connection, companies should keep in mind the SEC Chair’s recent admonition to ensure that non-GAAP financial measures are used appropriately in both SEC-filed documents and other, less formal communications such as earnings calls and releases.) 13 Equally important, companies should consider the need to file, as proxy materials, any written communications prepared by or on behalf of directors that are provided to shareholders in this context, depending on the timing of these communications and their relationship to any matters to be submitted to a shareholder vote at an annual or other meeting of shareholders. 2.

Understanding the Spectrum of Shareholder Views To understand the increasing shareholder emphasis on engagement and transparency, particularly as these twin objectives come into play in drafting the upcoming annual report and proxy statement and in preparing for the annual meeting, it is important for a company’s board and management to recognize the spectrum of views likely to be found within the company’s own shareholder base on such issues as corporate objectives, the time horizon for realizing these objectives and a variety of ESG issues. In this connection, it may be helpful to step back and consider how current trends in shareholder activism and recent public stands by major institutions may influence the voting and investment behavior of your shareholders. Current Trends in Activism Today the term “activism” encompasses a wide variety of investor priorities and views – from “traditional” governance matters such as separation of the roles of CEO and board chair, elimination of classified boards and now proxy access, to changes in capital allocation policies and the more immediate realization of economic returns, to a host of sustainability issues such as disclosure of corporate political contributions and lobbying expenses, human rights and sustainability reporting. It is becoming increasingly difficult to divide shareholders into the traditional categories of those focused on long-term equity ownership and therefore long-term corporate performance goals; hedge funds and others seeking short-term profitability and a quick exit; single-issue governance activists; and those primarily concerned with environmental/social/human rights issues.

For example, a combination of specific ESG concerns prompted the New York City Comptroller to launch an unprecedented proxy access campaign last year and to expand this campaign in 2016. 14 See Part 3 below. Activist hedge funds launched 360 publicly announced campaigns during 2015, compared to 301 during 2014. 15 The actual number of activist campaigns is likely much higher, as it is estimated that less than a third become public.

16 During 2015, activists focused on promoting M&A transactions and strategic corporate alternatives such as spinoffs, split-offs, or divestitures; operational improvements; changes in the board and/or management; and immediate returns of value to shareholders through special dividends or share buybacks. One estimate of the “success rate” of publicly announced campaigns finds 62.5% of such campaigns at least partially successful in achieving their desired outcomes in 2015, up from 59.9% in 2014. 17 Contributing to that success was support from mutual funds and public pension funds, which, in some cases, even partnered with activist investors in their campaigns.

For example, the percentage of dissident proxy cards that BlackRock, T. Rowe Price and Vanguard have voted to support has increased every year since 2011. 18 Mutual funds sided with Starboard in a successful campaign to replace the entire board of Darden Restaurants and in a campaign at General Motors.

19 Furthermore, CalSTRS, the second largest pension fund in the US, is increasingly investing in, or Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 4 . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance co-investing with, activist funds that targeted individual companies such as DuPont, PepsiCo and Perry Ellis International. Perhaps the most significant development in shareholder activism during 2015 has been the increase in settlements between activists and target companies. In a recent survey, over 90% of the most prolific activists noted that they found it less difficult to reach a resolution with management than in prior years. 20 In particular, companies increasingly are granting activists board seats as part of a settlement. Recent high-profile settlements include ConAgra Foods agreeing to a board settlement with Jana Partners, and Trian naming an advisor to the board of PepsiCo and gaining two board seats at Sysco and a board seat at BNY Mellon. In some instances, companies have even welcomed activists as significant investors.

In October 2015, Trian Partners (founded by activist Nelson Peltz) announced that it had invested $2.5 billion to become a top ten shareholder of GE, the result of dialogue between Mr. Peltz and members of GE management.21 Mr. Peltz, who reportedly did not request a board seat for Trian, issued a white paper faulting the stock market for undervaluing GE.

22 The Institutional View While the interests of hedge funds and institutional investors may align in certain circumstances, major institutional shareholders and asset managers have taken a public stand on the importance of companies taking a long-term approach to creating value. For example, in his April 2015 letter to CEOs, BlackRock Chairman and CEO Laurence D. Fink strongly advocated this approach despite “the acute pressure, growing with every quarter, to meet short-term financial goals.” Mr.

Fink acknowledged that returning capital to shareholders can be “a vital part of a responsible capital strategy,” and that some activists take a long-term view and foster productive change. However, he expressed deep concern that many companies have undertaken actions such as stock buybacks or increased dividends to deliver immediate returns to shareholders “while underinvesting in innovation, skilled workforces or essential capital expenditures necessary to sustain long-term growth.” He indicated that BlackRock’s “starting point” is to support management, particularly during difficult periods. Making a compelling case for enhanced transparency, however, Mr.

Fink emphasized that this is more likely to occur where management has articulated its strategy for sustainable long-term growth and has offered credible metrics against which to assess performance. 23 BlackRock and Vanguard have both publicly cautioned that they will actively engage with companies on governance factors that, in their view, detract from long-term, sustainable financial performance.” 24 For example, in his February 2015 letter to independent board leaders (also discussed in Part 1 above), Vanguard Chairman and CEO McNabb stated that “some have mistakenly assumed that our predominately passive management style suggests a passive attitude with respect to corporate governance. Nothing could be further from the truth.” Vanguard espouses six governance principles: (1) a substantially independent board with independent board leadership; (2) accountability of management to the board and of the board to stockholders; (3) shareholder voting rights consistent with economic interests (one share, one vote); (4) annual director elections and minimal anti-takeover devices; (5) executive compensation tied to the creation of long-term shareholder value; and (6) shareholder engagement.

The voting record of the Vanguard funds for the 12 months ended June 30, 2015 indicates that the funds largely supported management’s nominees and say-on-pay and other proposals. However, there are clear instances in which the funds used their voting power to signal a need for improvement or to effect changes in the board. Because the pace and pressures of shareholder activism continue to escalate, it is all the more important for a company’s management and board to meet the institutional calls for meaningful ongoing engagement and to prepare for activism even during periods of relative calm and corporate profitability. We offer some suggestions below for anticipating and addressing an activist challenge, recognizing that each company must formulate its own approach in light of the relevant facts and circumstances. Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 5 .

SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance What To Do Now: â— Review Business and Governance Strategies. Management and the board should regularly review the company’s business strategy, capital return policy, analyst and investor perspectives, as well as executive compensation and other governance issues in light of the company’s particular needs and circumstances and adjust strategies and defenses to meet changing market conditions. Companies should proactively address reasons for any negative management and/or corporate performance issues, and understand both how an activist might advocate increasing short-term shareholder value (e.g., through spin-offs and divestitures or financial engineering such as stock buybacks and increased debt) and vulnerabilities in the company’s response to such criticisms. Activists often use a company’s short-term performance problems or perceived governance, compensation, ethics or compliance issues to attract support from institutional investors. â— Review Board Composition and Tenure.

Board composition and, in particular, tenure issues are “low-hanging fruit” from an activist’s perspective. As we discuss in Part 6 below, institutional investors have been vocal about the importance of companies having the right mix of directors in terms of tenure, independence, experience and skills relevant to the company’s present needs and, in some cases, diversity. There is increased focus on whether long tenure compromises independence, and whether reliance on bright-line stock exchange tests is sufficient to establish independence in all circumstances.

Nominating committees should take a proactive approach to evaluating these factors and reviewing the policies and processes used for board refreshment and selfevaluations. As we note throughout this Alert, the upcoming proxy statement offers a prime opportunity to present the board’s considered approach to these matters. â— Think Like an Activist and Prepare. Management and the board should think like an activist and assess preemptively where the company’s possible governance, financial and operational weaknesses (as well as its strengths) lie.

Management and the board should work with outside advisers to prepare and develop a response plan for activism. â— Know Your Shareholders. As discussed in Part 1 above, companies should know who their major shareholders are and cultivate good relationships with them throughout the year, not just during proxy season. Not only should companies listen carefully to their shareholders and other important stakeholders, but they also should communicate a consistent message to the public regarding their business strategies and performance goals.

In particular, the best case for voting in favor of the company’s board nominees and/or other management-proposed agenda items should be made clearly and concisely in both the proxy statement and other, less formal written or oral communications with shareholders. â— Stay Informed. Companies should educate themselves on the voting policies and guidelines of their major investors before engaging with them. Boards should be fully and regularly informed of shareholders’ views and public perceptions of the company’s governance structure and performance, and should not rely unduly on management to provide the requisite information.

Directors should ask questions and should not make the mistake of assuming, for example, that large institutional investors vote in lock-step with proxy advisory firm recommendations. Although activists may bring a new perspective that cannot be ignored, the board ultimately has the fiduciary duty to make independent judgments about what is in the best interest of the company and its shareholders. â— Monitor Movements in Share Ownership. Monitor significant movements in share ownership and public sentiment about the company, including but not limited to those of analysts, proxy advisors, major institutional shareholders and other relevant constituencies. â— Understand the Company’s Defense Profile.

Companies should periodically review their bylaws, including the advance notice provisions, in light of changes in applicable state corporate law and the market environment. As many companies move to de-stagger their boards and otherwise dismantle longstanding takeover defenses in response to investor demands, an effective advance notice bylaw provision has become increasingly important. Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 6 . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance On the Horizon: Universal Proxy Ballots The Staff of the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance is currently working on rulemaking recommendations for the implementation of universal proxy ballots in contested elections. Existing federal proxy rules, state law requirements and practical considerations make it virtually impossible for shareholders in a contested election to choose freely among management and proponent nominees on each side’s proxy cards, unless they attend and vote in person at the shareholders’ meeting. As a result, shareholders executing a proxy card currently must choose between voting for the entire slate of candidates put forward by management or voting for the slate put forth by the proponent.25 The adoption of a universal proxy ballot system would mean that a single proxy card would list both management and proponent nominees and allow shareholders to vote for a mix of nominees in a contested election. Some have argued that the existing system favors management’s nominees and that a universal ballot would serve to bolster activist campaigns, particularly when seeking minority board representation. On the other hand, a universal ballot could help management limit the impact of an activist’s campaign by recommending that shareholders vote for only certain nominees on the dissident’s slate. Recent events have signaled that rulemaking could be imminent.

In 2014, the Council of Institutional Investors (CII) reignited interest in universal ballots with a petition to the SEC requesting an amendment to the proxy rules to facilitate their use. 26 In February 2015, the SEC hosted a Proxy Voting Roundtable that included a panel discussion on this topic. 27 In April 2015, The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) submitted a supplement to the Proxy Voting Roundtable in which it provided its written endorsement for the use of universal ballots.

28 SEC Chair Mary Jo White championed a universal ballot rulemaking initiative in a June 2015 speech, 29 urging companies not to wait for the SEC to act and to “[g]ive meaningful consideration to using some form of a universal proxy ballot even though the proxy rules currently do not require it.” 30 Specific issues the Staff is grappling with in connection with this rulemaking initiative include: (1) whether universal ballots should be optional or mandatory for all parties in an election contest; (2) how the ballots should look and whether both sides should be required to use identical universal ballots; (3) whether universal proxies should be available in all contests or just in “short slate” elections; (4) whether any eligibility requirements to use universal ballots should be imposed on shareholders; and (5) what timing, filing and dissemination requirements should be imposed on shareholders seeking to use universal ballots. 3. Keeping Up With Fast-Moving Proxy Access Developments “Proxy access” represents another turning point in the corporate governance of public companies. Designed to enable shareholders to use a company’s proxy statement and proxy card to nominate one or more director candidates of their own, it is increasingly gaining acceptance as corporate behemoths such as Apple, General Electric, Microsoft, IBM, Chevron, Coca-Cola, Merck, Staples, McDonald’s, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase and others adopt proxy access bylaws. Proxy access came to the forefront during the 2015 proxy season through Rule 14a-8 proposals submitted by certain pension funds and other governance-oriented activists, including 75 proposals submitted by the Boardroom Accountability Project launched by the New York City Comptroller and the New York City Pension Funds.

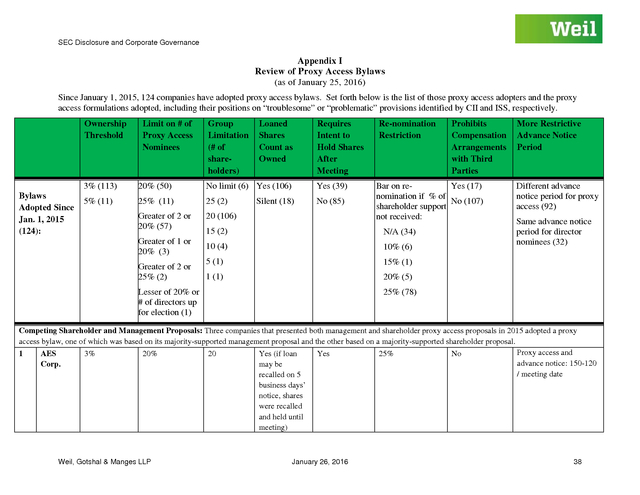

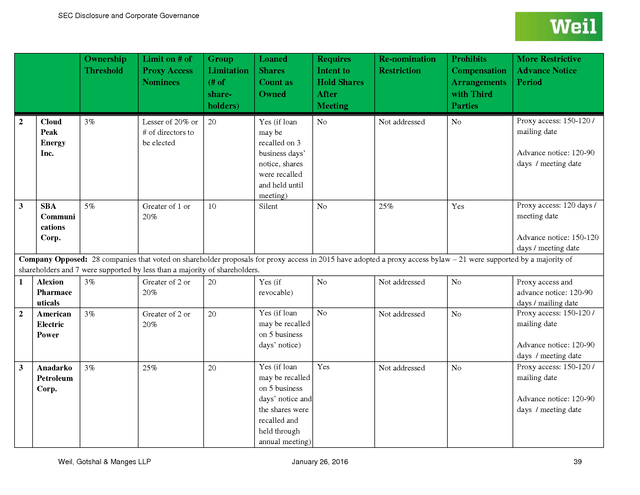

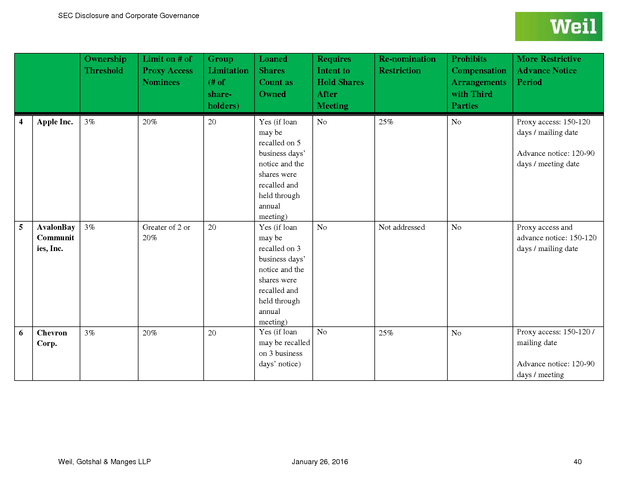

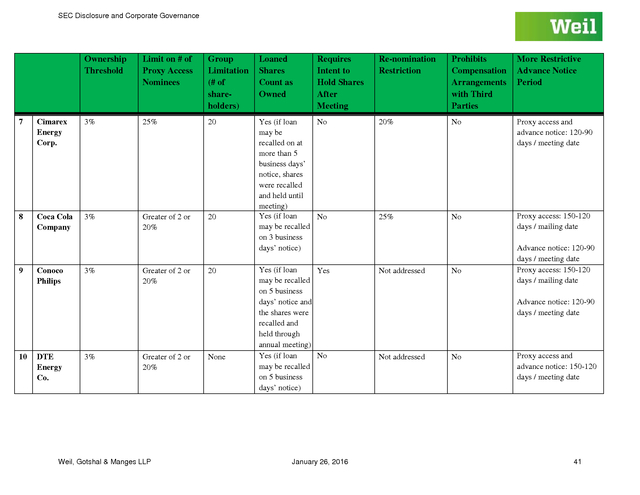

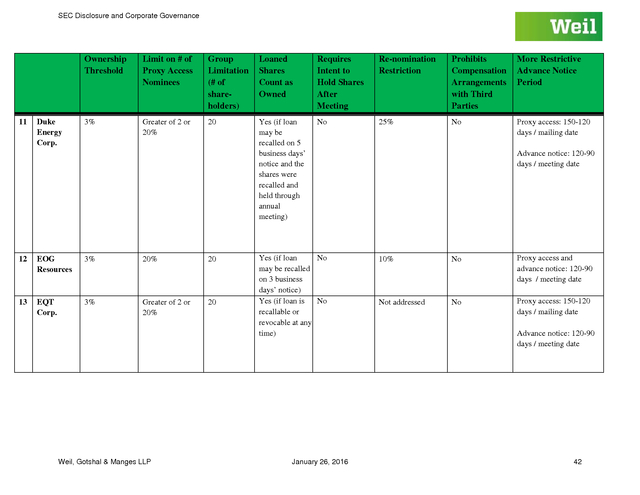

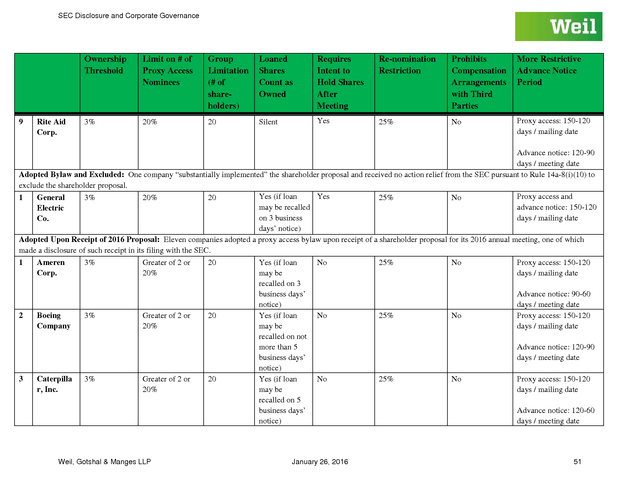

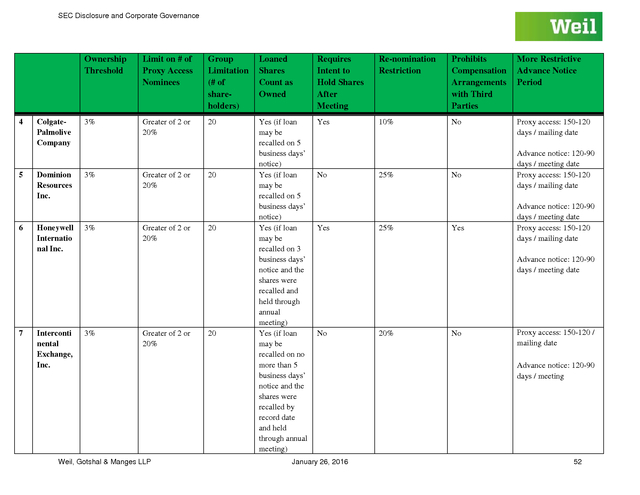

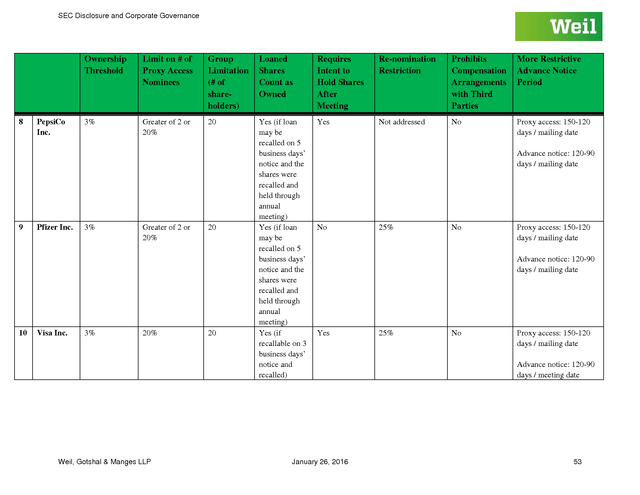

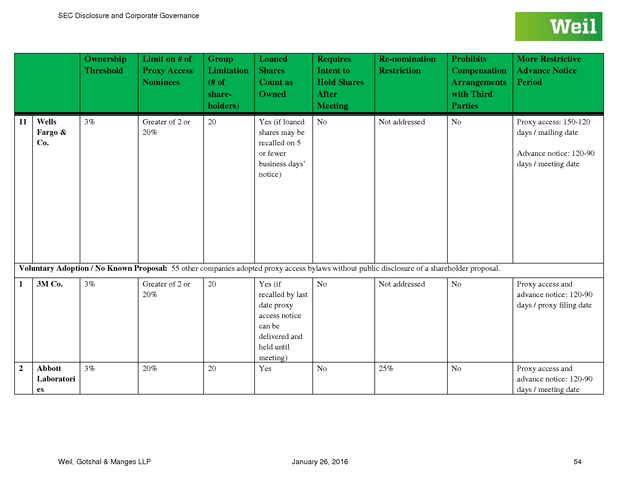

In 2015, over 91 proxy access proposals were submitted to a shareholder vote, with 55 receiving majority support. 31 Since January 1, 2015, 124 companies have adopted proxy access bylaws, whether voluntarily or in response to a shareholder proposal, and a recent uptick in companies implementing proxy access indicates that many boards have been addressing the topic in anticipation of their 2016 annual meetings. 32 It remains to be seen whether, this season, any of the companies that have adopted proxy access will face the first round of proxy access nominees.

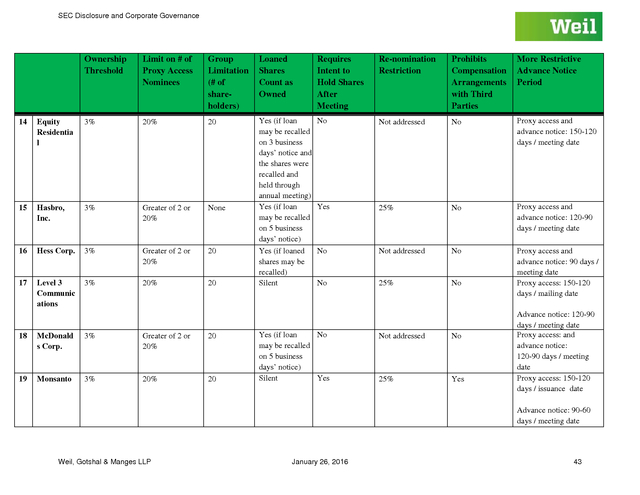

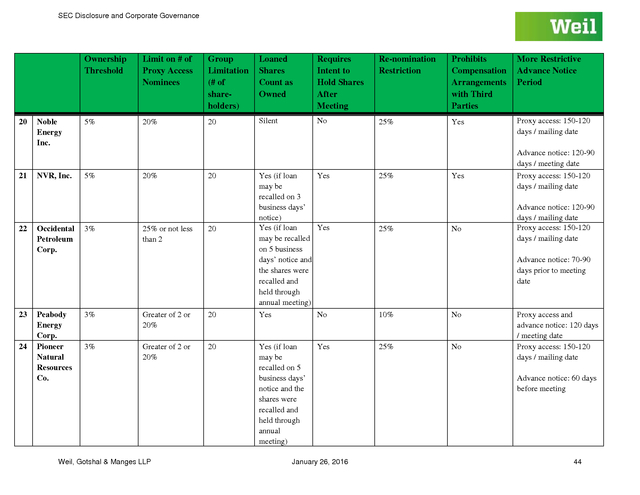

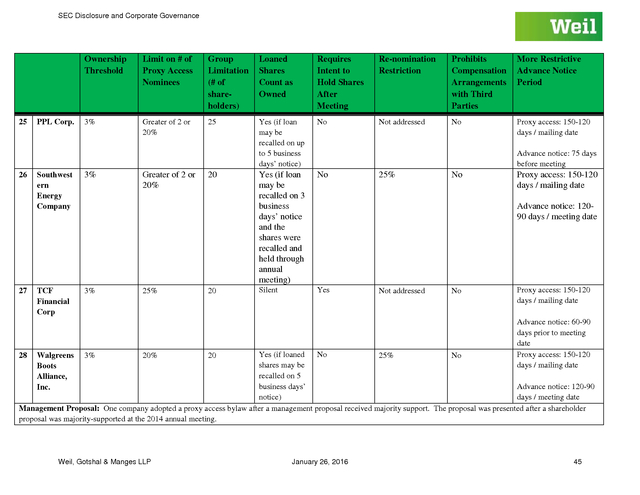

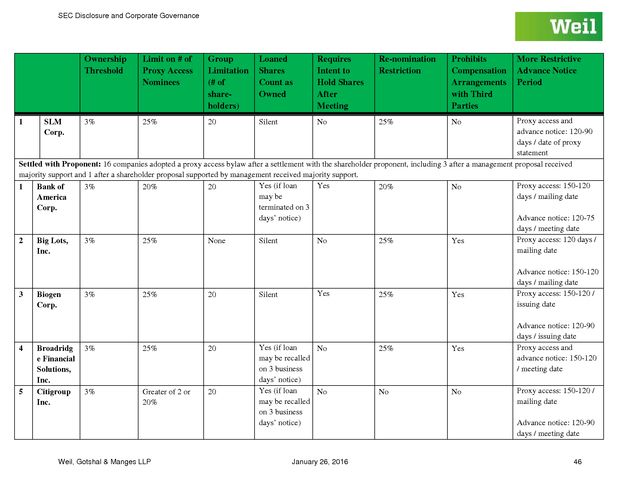

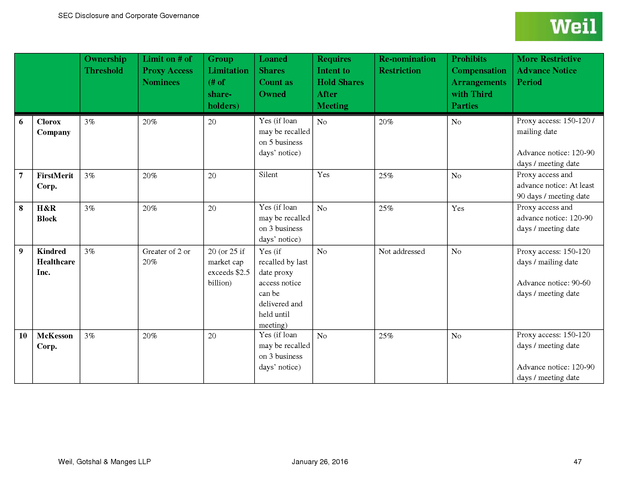

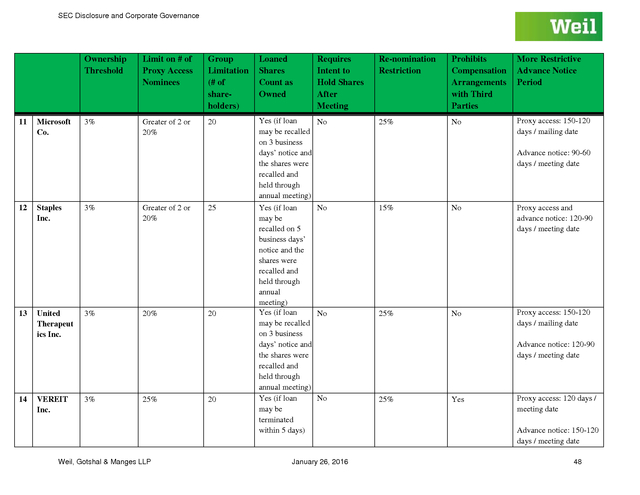

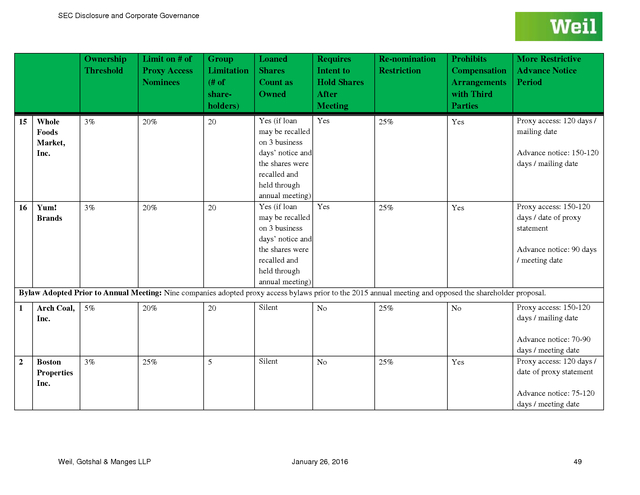

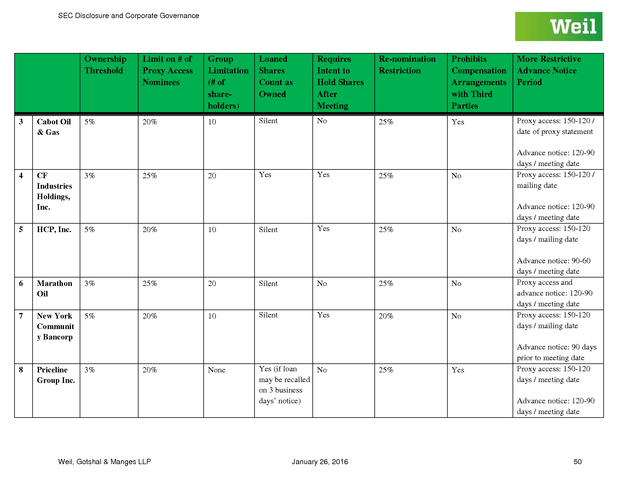

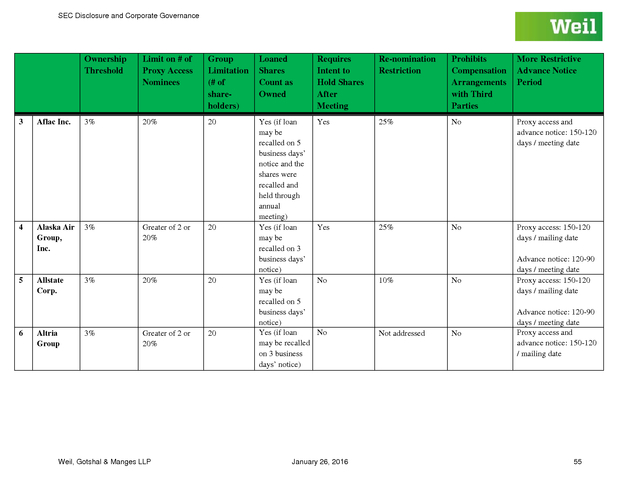

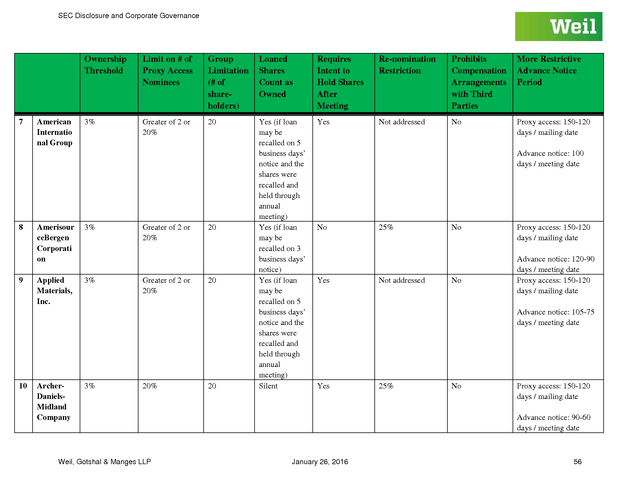

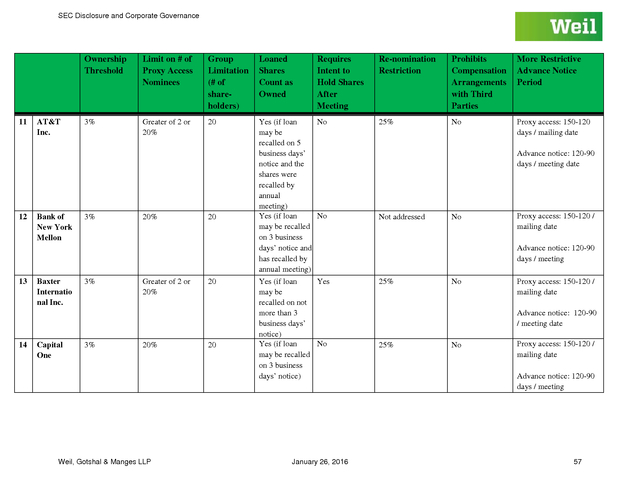

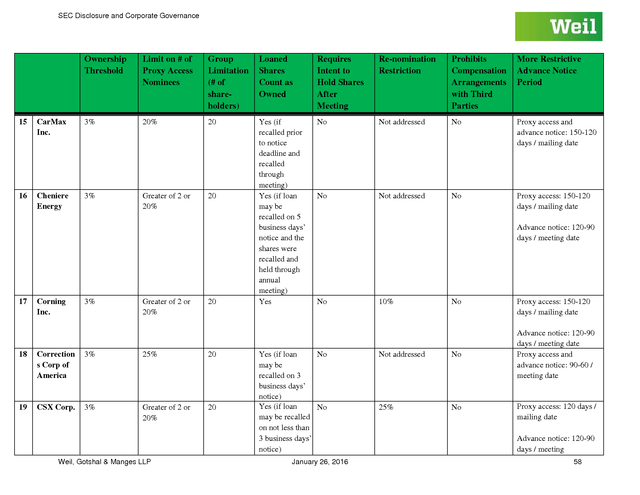

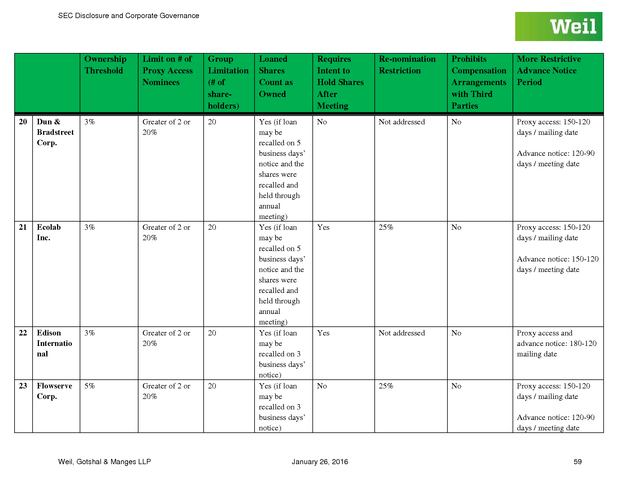

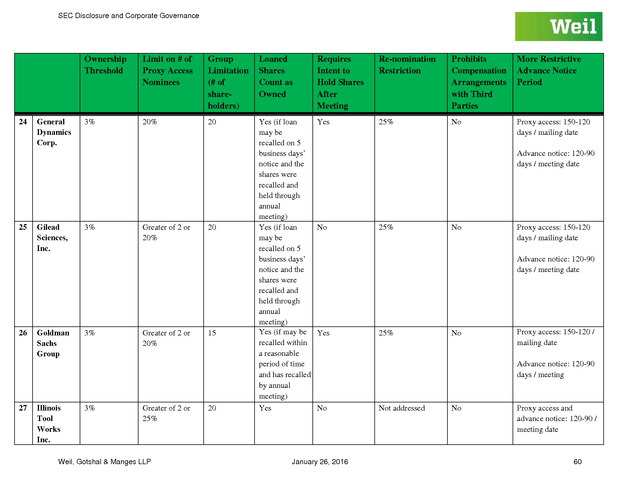

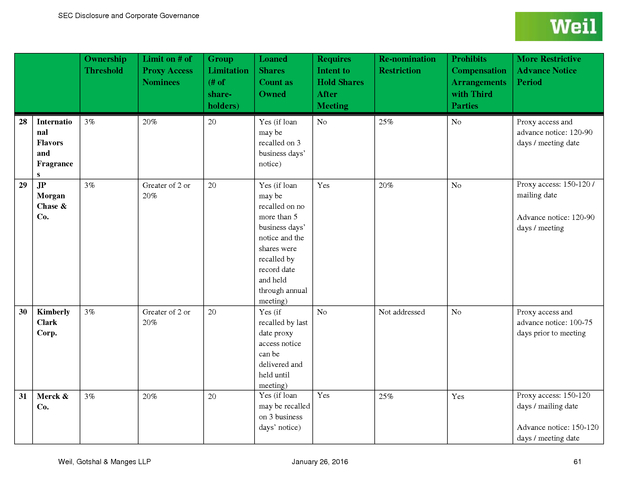

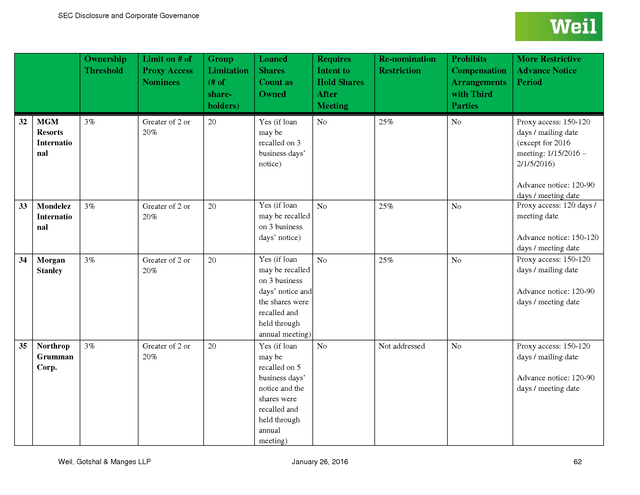

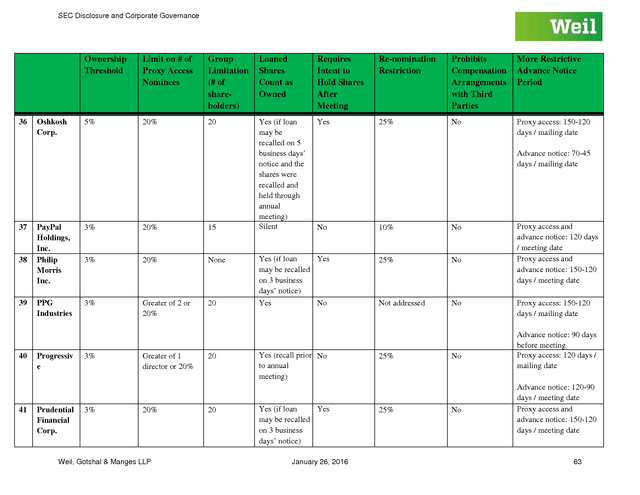

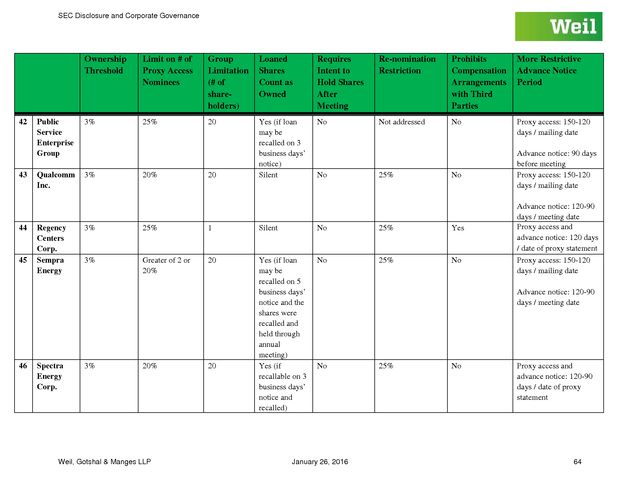

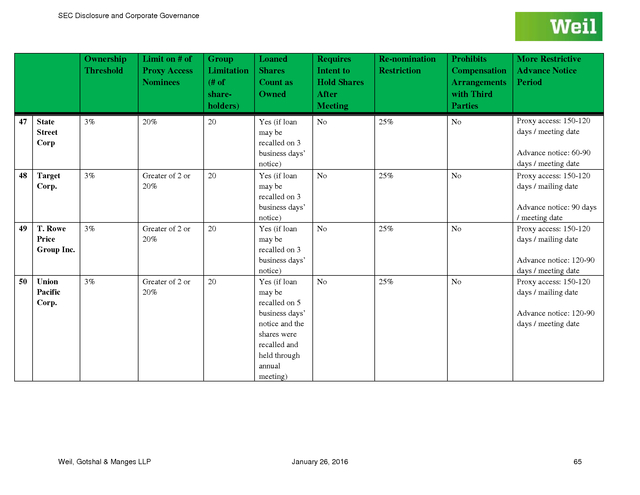

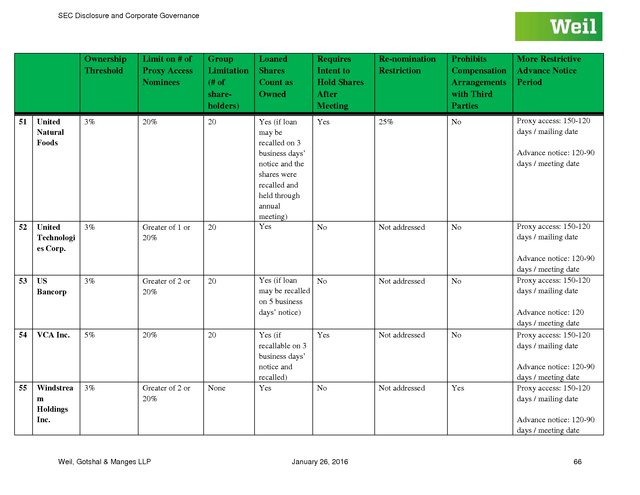

In Appendix I, we provide the list of companies that have adopted proxy access bylaws since January 1, 2015. Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 7 . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance Proxy access bylaws adopted during 2015 by and large contained the following formulation: 3% ownership / 3-year holding period / 20 shareholder aggregation limit / 20% of the board limit. We anticipate that, for the 2016 proxy season, attention will turn to more granular issues, including those that have been identified as “troublesome” by CII or “problematic” by ISS. ISS’s recent FAQs, which are discussed in our recent Alert available here, provide guidance on how ISS will determine whether a board-adopted proxy access bylaw qualifies as “responsive” to a majority-supported shareholder proposal or whether it is too restrictive to qualify as “responsive” and therefore could result in a negative recommendation against the election of directors. “Especially” and “Potentially” Problematic Provisions ISS views the following as “especially” problematic provisions that effectively nullify the proxy access right: (1) aggregation limits that count individual funds within a mutual fund family as separate shareholders; and (2) a requirement to hold company shares after the annual meeting. While proxy access bylaws adopted in 2015 generally did not include an aggregation limit on funds within a mutual fund family, more than half of the proxy access bylaws adopted in 2015 include provisions that require nominating shareholders to provide a statement of intent to maintain ownership after the meeting.

We expect that the requirement to hold company shares after the annual meeting will cause many companies that have already adopted a proxy access bylaw to revisit their bylaw. ISS also identified five other provisions as “potentially” problematic, especially when used in combination: (1) prohibitions on resubmission of failed nominees in subsequent years; (2) restrictions on third-party compensation of proxy access nominees; (3) restrictions on the use of proxy access and proxy contest procedures for the same meeting; (4) how long and under what terms an elected shareholder nominee will count towards the maximum number of proxy access nominees; and (5) when the right will be fully implemented and accessible to qualifying shareholders. Every proxy access bylaw adopted in 2015 contains one or more of these provisions; however, it is not clear which provisions in a proxy access bylaw, either individually or in combination, will rise to the level of “problematic.” Institutional investors have not publicly taken positions on these “problematic” provisions. However, certain institutions such as T.

Rowe Price, which implemented proxy access in December 2015, and BlackRock, which intends to present a proxy access proposal at its May 2016 annual meeting, 33 may provide insight into their positions through their own proxy access bylaws. For example, T. Rowe Price’s proxy access bylaw disqualifies resubmitted proxy access nominees who did not receive at least 25% support in the prior year’s election, but it does not restrict the use of proxy access and proxy contest procedures for the same meeting.

34 Round 2 of the Boardroom Accountability Project and Other Recent Proposals Thus far for the 2016 season, we have seen proxy access proposals from James McRitchie and John Chevedden that focus on the following provisions: (1) requiring that the number of shareholders forming a group be “unrestricted”; (2) setting the number of access candidates appearing in proxy materials at one-quarter of the directors then serving but in no event less than two; and (3) requiring that the nomination or renomination of access nominees not be subject to any restrictions that do not apply to other board nominees.” 35 On January 11, 2016, the New York City Comptroller announced that, in an expansion of the Boardroom Accountability Project, the New York City Pension Funds had submitted proxy access proposals to 72 companies. Of these, the Comptroller said 36 had received a second round of proposals because they had not yet instituted or agreed to institute a “3% bylaw with viable terms.” The Comptroller noted that these recipients included companies that had instituted “unworkable bylaws requiring 5% ownership.” The Comptroller described the other 36 linkage companies, which were receiving proposals for the first time, as including 18 of the New York City Pension Funds’ largest portfolio companies, 7 coal-intensive utilities, 9 board diversity “laggards” and 9 with excessive CEO pay. The Comptroller also noted that a total of 15 of its 2016 proposals have been withdrawn to date (6 from the first group and 9 from the second) after the companies instituted, or agreed to institute, a 3% bylaw. In contrast with the McRitchie and Chevedden proposals, the Comptroller’s proposals for the 2016 season appear to mirror those Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 8 . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance submitted during the 2015 season and do not preclude companies from including limits on aggregation or additional limitations on proxy access. The companies from which the Comptroller’s proposals have been withdrawn have all adopted proxy access bylaws that limit the number of proxy access nominees to the greater of 2 or 20% of the board and also limit to 20 the number of shareholders that may aggregate their shares. 36 Many companies that recently adopted proxy access bylaws in connection with receiving a shareholder proposal have sought relief from the SEC under Rule 14a-8(i)(10) to exclude the proposal, on the ground that it has been substantially implemented (as GE successfully contended in 2015). 37 While bylaws include various combinations of the “troublesome” and “problematic” provisions identified by CII and ISS, respectively, these companies maintain that their adoption of proxy access achieves the “essential objective” of the proposal – to adopt a proxy access right – which the SEC noted in its response to GE.

38 We have yet to see the SEC’s response to these recent no action requests. See Part 4 below. What To Do Now: â— Understand the Positions of Key Shareholders on Proxy Access. Working with their proxy solicitors, companies that have not adopted access, or that have adopted an earlier version of access, should educate themselves about the positions of their institutional investors on access generally, as well as on specific access provisions, to see how they would impact the vote on an access proposal at their 2016 annual meeting. â— Evaluate Alternatives for Addressing Proxy Access.

Depending on the company’s experience to date and its approach to shareholders’ governance initiatives, there are three basic ways to address proxy access in 2016. In our recent Alert available here, we provide a strategic roadmap to help companies and their boards consider these alternatives: (1) wait-and-see, prepare and engage; (2) adopt in advance of the 2016 annual meeting; or (3) put a management proposal on the ballot. Note that doing nothing is not really an option. â— Consider How Proxy Access Would Actually Play Out for Your Company.

Understanding how a proxy access bylaw works and how it would fit into your proxy season calendar and process is important for to developing a position on various elements of a proxy access bylaw. â— Prepare a Draft Bylaw to Keep “On the Shelf.” For companies that have not yet adopted proxy access, putting together a draft bylaw will provide an opportunity to thoughtfully consider all of the complexities and choices before it becomes a matter of urgency. 4. Anticipating Other Shareholder Proposals In 2015, shareholders submitted more than 1,030 proposals to approximately 540 companies, of which 45% related to environmental and social issues, nearly 43% were governance-related and about 12% addressed compensation topics. 39 See Part 7 below.

We expect to see more shareholder proposals on the ballot in 2016, particularly given what seems to be a more conservative position by the SEC Staff on the excludability of many proposals. When is a Proposal “Conflicting” and thus Excludable under Rule 14a-8(i)(9)? After imposing a moratorium in 2015 on the use of Rule 14a-8(i)(9) to exclude shareholder proposals based on the inclusion of a “conflicting” management proposal, the SEC Division of Corporation Finance issued Staff Legal Bulletin No.14H (CF) on October 22, 2015 40 and resumed processing companies’ (i)(9) no-action requests. Under the new guidance, a company will not be able to exclude a shareholder proposal under (i)(9) unless the shareholder proposal “directly conflicts” with the management proposal. A proposal will not be found to “directly conflict” unless “a reasonable shareholder could not logically vote in favor of both proposals” – meaning that a vote for one proposal would be tantamount to a vote against the other proposal.

We expect that this guidance will severely limit the use of (i)(9) as a basis for excluding shareholder proposals. In SLB 14H, the Staff offered the following examples of proposals it would exclude because of direct conflicts: (1) where a company seeks votes to approve a merger and the shareholder proposal seeks votes against; and (2) where a Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 9 . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance shareholder proposal seeks to separate the positions of chairman and CEO and the company seeks approval of a bylaw requiring these positions to be combined. The Staff also offered the following examples of shareholder proposals it would not consider to be in direct conflict because, in the staff’s view, both proposals have similar objectives and a reasonable shareholder could prefer one proposal over the other but logically vote for both: (1) where the company proposes a proxy access bylaw with one ownership level/holding period/board seat limit and the shareholder proposal has a different formulation; and (2) where the shareholder proposal seeks an equity award policy with minimum 4-year vesting and the company proposes an incentive plan that gives the compensation committee discretion to set vesting. The Staff’s guidance may breathe new life into proposals calling for shareholder rights to call special meetings, which companies had previously been able to exclude pursuant to (i)(9) by simply proposing a different ownership threshold (e.g., a shareholder proposal at 10% was previously excludable as conflicting with a management proposal at 20%). Companies can seek to engage with shareholders to reach a middle ground, or be prepared to place two proposals with different thresholds on the ballot. When is a Proposal Related to “Ordinary Business Operations” and thus Excludable under Rule 14a-8(i)(7)? In SLB 14H, the Staff also reaffirmed the historical interpretation that proposals that focus on a significant policy issue transcend a company’s ordinary business operations and therefore are not excludable under Rule 14a-8(i)(7). The guidance referred to the Trinity Wall Street v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.

case, 41 which originated with a shareholder proposal requesting that the charter of Wal-Mart’s nominating and governance committee be amended to add oversight of policies and standards governing Wal-Mart’s decision whether or not to sell guns. The Staff granted Wal-Mart’s request to exclude the proposal on the ground that it related to Wal-Mart’s ordinary business operations and did not focus on a significant policy issue. The U.S.

Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit also ruled in favor of Wal-Mart’s ability to exclude the proposal. In doing so, however, the majority opinion introduced a two-part test as to when the (i)(7) exception would apply: first, the shareholder proposal must focus on a significant policy issue, not just “the choosing of one among tens of thousands of products it sells,” and second, the subject matter of the proposal must “transcend” the company’s ordinary business operations, meaning that the policy issue must be “divorced from how a company approaches the nitty-gritty of its core business.” In SLB No. 14H, the Staff stated that it will not follow the “new analytical approach” introduced by the Third Circuit, which it believes could lead to the unwarranted exclusion of shareholder proposals.

Rather, the Staff will continue to interpret (i)(7) consistent with the SEC’s historical practice, and the concurring opinion in the Wal-Mart case: “a proposal may transcend a company’s ordinary business even if the significant policy issue relates to the ‘nitty-gritty of its core business’.” We are seeing this interpretation unfold for the 2016 proxy season as the SEC declines relief to companies that submitted no-action requests on the basis of an (i)(7) exclusion in response to a shareholder proposal for boards to adopt and issue (or amend) a general payout policy to give preference to share repurchases over cash dividends as a method of returning capital to shareholders. 42 For more detail on the SEC guidance on when proposals “directly conflict” and when “a proposal may transcend a company’s ordinary business” see our recent Alert available here. When is a Proposal “Substantially Implemented” and thus Excludable Under Rule 14a-8(i)(10)? Finally, companies facing a proxy access proposal, and those that have already adopted proxy access, are also considering their ability to exclude a shareholder proposal on the ground that the company has “substantially implemented” the proposal under Rule 14a-8(i)(10). For example, in 2015, GE successfully sought no-action relief pursuant to (i)(10) to omit a shareholder proposal from its proxy statement on the basis that GE had already “substantially implemented” proxy access.

The bylaw adopted by GE mirrored the proposal in requiring 3% ownership and a 3-year holding period and in limiting access nominees to 20% of the board. However, while the proposal referred to nominations by a “shareholder or group,” the bylaw imposed a 20-shareholder aggregation limit. Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 10 . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance The SEC noted GE’s representation that “the board has adopted a proxy access bylaw that addresses the proposal’s essential objective.” 43 Going forward, it is unclear where the SEC will draw the line on “substantially implemented,” or how closely a company’s proxy access bylaw will need to track the proponent’s version in order to meet the requirements of (i)(10). The increasingly granular focus by CII, ISS and others on bylaw provisions they consider unacceptable could inform the Staff’s views on “substantially implemented.” 5. Considering the Impact of ISS and Glass Lewis Voting Policy Updates In November 2015, ISS and Glass Lewis updated certain aspects of their proxy voting policies effective for the 2016 proxy season. The key changes are discussed briefly below; for more information, please see our Alert, dated November 23, 2015, available here.

On December 18, 2015, ISS released non-compensation-related FAQs 44 and, on the same date, two additional sets of FAQs related to U.S. executive compensation policies (available here 45) and equity compensation plans (available here 46). Overboarding Citing an “explosion” in the time commitment needed for board service, both ISS and Glass Lewis have lowered from 6 to 5 the maximum number of public company directorships a director (other than the CEO) may have before being considered “overboarded.” For the CEO, ISS has kept the ceiling at 3 (counting subsidiary boards separately); Glass Lewis has lowered it to 2. ISS and Glass Lewis both provide a one-year transition period: overboarding in 2016 will result in cautionary language in the proxy voting report; in 2017, a negative recommendation.

In the case of overboarded CEOs, ISS will not recommend against the CEO for election to the board of the company where he or she serves as CEO or to the board of any controlled (>50%) subsidiary. However, ISS may on a case-bycase basis recommend against a CEO’s election to outside boards and to the boards of subsidiaries of the public company where the CEO serves that are not controlled (<50%). In this regard, it is worth noting that SEC Chair White has expressed concern that overboarding may detract from effective audit committee service.

See Part 8 below. Proxy Access ISS’s new FAQs provide guidance on how ISS will evaluate a board’s responsiveness to a majority-supported shareholder access proposal. ISS has also provided a framework to evaluate candidates nominated by proxy access. ISS added proxy access as a “zero weight” factor for QuickScore 3.0 (likely presaging a weighting next year). Glass Lewis has not provided any new insight into how it will evaluate shareholder proposals on proxy access, or which proxy access bylaw provisions will be considered so restrictive as to call into question a board’s responsiveness to a majority-supported shareholder proposal, but has offered some guidance on how it reviews conflicting proposals. See Part 3 above. Unilateral Board Actions Directors of IPO companies are for the first time expressly subject to ISS issuing a negative recommendation if, prior to or in connection with the IPO, the company’s board adopted charter or bylaw amendments that ISS believes materially diminish shareholder rights.

At existing public companies, amendments to (1) classify the board, (2) establish supermajority vote requirements or (3) eliminate shareholders’ ability to amend bylaws will result in ISS issuing a negative recommendation against directors until such time as the rights are restored or the unilateral action is ratified by a shareholder vote. Insufficient Compensation Disclosure by Externally-Managed Issuers (EMIs) ISS will now generally recommend against say-on-pay where insufficient compensation disclosure (e.g., disclosure of only the aggregate management fee) precludes a reasonable assessment of pay programs and practices applicable to the EMI’s named executive officers. Many REITs are EMIs. Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 11 . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance Shareholder Proposals Seeking Environmental and Social Disclosure ISS has clarified and somewhat broadened the criteria it will consider in evaluating shareholder proposals seeking company reports on (1) animal welfare, (2) pharmaceutical pricing and related matters and (3) climate change/greenhouse gas emissions. In the case of animal welfare, the criteria are now broadened to address practices in the supply chain relating to the treatment of animals. See Part 7 below. Conflicting Management and Shareholder Proposals Glass Lewis now specifies the factors it will consider in assessing conflicting shareholder and management proposals. This is of increasing importance in light of the SEC’s recent indication that it will strictly construe whether a shareholder proposal is truly “conflicting” and therefore qualifies for exclusion under Rule 14a-8(i)(9). See Part 4 above. Performance Failures Associated with Board Composition or Environmental or Social Risk Oversight Glass Lewis “may consider” recommending against the nominating committee chair where it believes a board’s failure to ensure that it has directors with relevant experience, either through periodic director assessment or board refreshment, has contributed to the company’s “poor performance.” (Glass Lewis did not indicate how it will establish that board composition has contributed to “poor performance” or how it will define such performance.) Glass Lewis also has indicated that, where the board or management has failed to sufficiently identify and manage a material environmental or social risk that either did – or could – negatively impact shareholder value, it will recommend voting against directors responsible for risk oversight.

See Part 6 below. Exclusive Forum Bylaws for IPO Companies For newly public companies, Glass Lewis will no longer automatically recommend a vote against the nominating committee chair due to the presence of an exclusive forum bylaw at the time of the IPO. Instead, Glass Lewis will consider such provision in the context of a company’s overall shareholder rights profile. For a discussion of exclusive forum bylaws, see Part 10 below. What To Do Now: In addition to reviewing the guidance relating to specific proxy voting policy updates provided in our Alert, dated November 23, 2015, available here, we recommend that companies take the following steps: â— Evaluate Number of Directorships.

Evaluate whether your company’s directors, including the company’s CEO or other executive officers, could be at risk of receiving a public caution from ISS or Glass Lewis and, subsequently, a negative recommendation under the revised overboarding policies. Ensure that directors and executive officers update their annual questionnaires to provide current biographies, including all other boards on which they serve (both public and private). Companies should have a policy requiring prompt notice of changes in employment or directorships, and directors and executive officers should be periodically refreshed about this policy.

Directors and executive officers should be particularly mindful about potential overboarding that may arise from board service on private companies that anticipate an IPO. â— Carefully Consider Bylaw Amendments. Companies, including those preparing for an IPO, that are considering whether to amend their charter or bylaws in a manner that could be viewed by ISS to adversely impact shareholders should carefully consider the impact of such amendments on director elections but should continue to make decisions in the best interest of the company, especially during the IPO transition period. Companies that recently became public or are preparing for an IPO should note what may be a suggestion from ISS that disclosure of a public commitment to put any adverse shareholder provisions to a shareholder vote within three years of the IPO date may result in a period of “grace” during the company’s formative years in the public domain. Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 12 .

SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance â— Verify QuickScore Reports. Companies may verify data verification points at any time, except between the company’s proxy filing and shareholder meeting. â— Register with ISS for Equity Compensation Scorecard. Companies planning to seek shareholder approval of an equity compensation plan at the next annual meeting should register to gain access to the ISS Equity Plan Data Verification Portal and review the data points about the company that ISS will consider as part of its scorecard approach. â— Understand Vulnerabilities and Potential for Negative ISS Voting Recommendations. We encourage all companies to become familiar with the more than 45 circumstances in which ISS may recommended a negative vote regarding director elections (set forth in the Appendix to our Alert, available here), or on other proposals that may be included in their proxy statement. â— Review and Enhance Proxy Statement Disclosure.

Companies should review last year’s compensation and governance disclosure and consider any investor feedback with an eye toward further improvements. Clear, complete and concise proxy statement disclosure that highlights developments and explains the board’s rationale for its governance structure and board nominations in terms of the company’s present needs can be a company’s best tool for making its case to the proxy advisors – and shareholders generally. 6. Key Issues for the Nom/Gov Committee: Director Tenure, Independence, Gender Diversity and Skills Vanguard Chairman and CEO McNabb observed pointedly in a speech in October 2014 that board composition is the “single most important factor in good governance.” 47 Consistent with this view, the pressure on boards and nominating committees to justify the composition of the board continues to grow.

Shareholders and proxy advisory firms are focusing on various elements of board composition, including tenure, independence, gender diversity and relevant experience and skills. As discussed in Part 5 above, ISS and Glass Lewis are also zeroing in on the processes used for board nominations and board self-evaluations. ISS has updated QuickScore 3.0 to clarify that, for US companies, a “robust” director self-evaluation policy exists when the company discloses an annual board performance evaluation policy that includes individual director assessments and an external evaluation performed at least once every three years.

Glass Lewis, taking an even more aggressive approach, has revised its 2016 voting policies to include a new category pursuant to which it “may consider” recommending against the nominating committee chair where it believes a board’s failure to ensure that it has directors with relevant experience, either through periodic director assessment or board refreshment, has contributed to the company’s “poor performance.” Director Tenure While a relatively recent issue in the U.S., investors and regulators in the United Kingdom, France and other countries have been questioning for some time whether long-tenured directors can truly be independent. 48 Most U.S. institutional investors, as well as the proxy advisors, have not expressly favored term limits or bright-line cut-offs as a way of ensuring independence. 49 For example: â— CII’s policy focuses on board evaluation of director tenure and encourages boards to weigh whether a “seasoned director should no longer be considered independent.” 50 However, CII does not go so far as to endorse term limits or specify the number of years of board service that would make a director “seasoned.” â— BlackRock’s voting guidelines indicate that it generally will not vote in favor of shareholder proposals seeking the board’s adoption of bright-line term limits, but it will not oppose a particular board’s decision to impose such limits as a mechanism for board “refreshment.” 51 At the same time, BlackRock warns that it may withhold votes from “[t]he independent chair or lead independent director, members of the nominating committee, and/or the longest tenured director(s), where we observe a lack of board responsiveness to shareholders on board composition concerns, evidence of board entrenchment, insufficient attention to board diversity, and/or failure to promote board succession planning over time in line with the company’s stated strategic direction.” 52 Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 13 .

SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance â— On December 16, 2015, CalPERS’ Global Governance Policy Ad Hoc Subcommittee approved proposed revisions to the pension fund’s Global Governance Principles to require that companies take a comply-or-explain approach on the issue of long-tenured directors. Under the proposed revised principles, a company would have two options regarding a director who has served on the board for more than 12 years: either classify the director as non-independent or annually disclose a basis for continuing to deem him or her independence. 53 In contrast, in 2014 State Street Global Advisors adopted bright-line guidelines on for determining “excessive” director tenure (noting it generally will “take a skeptical view” of directors whose tenure exceeds nine years). 54 However, reportedly in that year State Street voted against the reelection of only 2% of directors pursuant to its policy, even though it found concerns around lack of board refreshment at approximately 13% of the companies. State Street cited productive dialogues with the companies as the reason for the low number of negative recommendations.

55 Rather than establish term limits, 73% of S&P 500 boards have established a mandatory retirement age for directors to promote turnover. Of those boards, 93% have a mandatory retirement age of 72 or older, which is a significant change from 57% in 2005 as director retirement ages increasingly skew older. In particular, while more than half of the companies with mandatory retirement ages have set the retirement age at 72 for the last ten years, there has been a 26% increase in the number of companies that have raised the age to 75 or older since 2005 (8% to 34%). ISS includes director tenure in its QuickScore governance rating system.

As discussed in Part 5 above, for 2016 ISS clarified that the presence of a “small number” of long-tenured directors (i.e., those on the board longer than 9 years) will not negatively impact the company’s QuickScore governance rating. QuickScore does not quantify the term “small number.” To date, we have generally found that companies receive a QuickScore “red flag” when longtenured directors constitute more than one-third of the board. Under ISS’s proxy voting policy applicable to management or shareholder proposals to limit the tenure of outside directors, whether through term limits or the adoption of a mandatory retirement age, ISS will “scrutinize boards where the average tenure of all directors exceeds 15 years for independence from management and for sufficient turnover to ensure that new perspectives are being added to the board.” 56 Glass Lewis takes a more flexible position on mandatory age or term limits, stating in its 2015 proxy voting guidelines that “[s]hareholders are better off monitoring the board’s approach to corporate governance and the board’s stewardship of company performance rather than imposing inflexible rules that don’t necessarily correlate with returns or benefits to shareholders.” But if a board does adopt such limits, Glass Lewis believes boards should “follow through” and not grant waivers.

57 The recent adoption by GE of a 15-year term limit for all directors other than the CEO, subject to a two-year transition period for directors serving on the board as of the 2016 annual meeting, may signal a movement among companies to use a bright-line standard to set director expectations about tenure in advance and establish a pathway for director refreshment. 58 Director Independence An issue closely linked to director tenure, and recently in the news, 59 is director independence. As noted above, investors such as State Street have become more vocal in questioning how independence is defined and whether independence is compromised after many years on the board.

60 An October 2015 decision by the Delaware Supreme Court in Delaware County Employees Retirement Fund v. Sanchez 61 placed a spotlight on the sometimes routine analysis of director independence, which in this instance was also linked to tenure. The Sanchez case illustrates that even if a director does not have a direct financial interest in a transaction, the director’s independence can be called into question based on long-standing close personal friendships and economically advantageous relationships. The plaintiffs in Sanchez challenged a transaction involving cash payments to Sanchez Resources, LLC, a private company wholly-owned by the family of A.R.

Sanchez, Jr., by Sanchez Energy Corporation, a public corporation of Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 14 . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance which Mr. Sanchez’s family was the largest stockholder and which was dependent on Sanchez Resources for all management services. Plaintiffs alleged that a pre-suit demand on Sanchez Energy’s five-member board of directors was excused. The parties agreed that two directors, the company’s Chairman (Mr.

Sanchez) and the company’s President (Mr. Sanchez’s son), lacked disinterestedness and independence, and the disinterestedness and independence of the board as a whole turned on the independence of a third director, Alan Jackson, with respect to the decision whether the corporation should sue Sanchez Resources. Plaintiffs alleged various relationships between Mr.

Jackson and Mr. Sanchez, including (1) a “50-year close friendship”; (2) a $12,500 donation by Mr. Jackson to Mr. Sanchez’s 2012 gubernatorial campaign; (3) Mr.

Jackson’s and his brother’s “full-time job and primary source of income” as executives at an insurance agency wholly-owned by a company of which Mr. Sanchez (whom the board of such company had determined was not independent under NASDAQ rules) was the largest stockholder and at which both Mr. Jackson and his brother worked on the Sanchez company accounts; and (4) the fact that Mr.

Jackson earned $165,000 as a Sanchez Energy director, representing approximately 30-40% of his total income in 2012. On the defendants’ motion to dismiss, the Court of Chancery concluded that the plaintiffs’ allegations were insufficient to overcome the presumption that Mr. Jackson was independent from Mr. Sanchez and dismissed the action for failure to adequately plead that demand was excused.

The Delaware Supreme Court reversed, stating that “Delaware courts must analyze all the particularized facts pled by the plaintiffs in their totality and not in isolation from each other” and “in full context,” and that in this case plaintiffs alleged “not only that the director had a close friendship of over half a century with the interested party, but that consistent with that deep friendship, the director’s primary employment (and that of his brother) was as an executive of a company over which the interested party had substantial influence.” The court stated that plaintiffs thus alleged more than a “thin social-circle friendship,” such as in the oft-cited decision in Beam v. Stewart,62 where allegations that “directors ‘moved in the same social circles, attended the same weddings, developed business relationships before joining the board, and described each other as ‘friends’” were held insufficient to establish a lack of independence. Some will argue that Sanchez stands for nothing more than the proposition that an individual is unlikely to sue a close friend of over half a century and someone who controls both his and his brother’s income. It is worth noting, however, that the board of Sanchez Resources Corporation had determined that Mr.

Jackson was an “independent director” as defined by the rules of the New York Stock Exchange,63 and that even directors who satisfy the NYSE’s bright line rules for independence may lack independence for some purposes. The case thus provides a warning to companies and their nominating committees, particularly in situations involving transactional or related party issues, that reliance on bright-line tests under applicable stock exchange rules may not be sufficient to determine the independence of directors for all purposes. A director’s relationship to a potentially interested party must always “be considered in full context.” Gender Diversity In a November 2015 speech, SEC Chair White cited U.S.

boardrooms as one of several areas that have been “stubbornly resistant” to progress in fostering gender diversity. 64 She noted that, in 2015, women comprised only 17.5% of Fortune 1000 company boards and 19.2% of S&P 500 company boards,65 while “[s]tudy after study shows that diversity of all kinds makes for stronger boards and companies.” A December 2015 report of the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that even if women were to join boards in equal proportions to men beginning in 2015, achieving parity in the boardroom could take more than four decades. 66 The call for greater gender diversity in the boardroom is resonating with some institutional investors.

The Thirty Percent Coalition, which cites support by representatives of investors with $3 trillion in assets under management, has been engaging in a multi-year letter-writing campaign directed to Russell 1000 companies, most recently including 160 companies in the S&P 500 and Russell 1000 that have no women on their boards.67 In 2013 the New York City Comptroller on behalf of the New York City Pension Funds filed a proposal with C.F. Industries Holdings, Inc., asking the board of directors to “include women and minority candidates in the pool from which Board nominees are chosen,” and report to shareholders “its efforts to encourage diversified representation on the board.” The proposal received a Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 15 . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance majority of shareholder votes. 68 BlackRock revised its proxy voting guidelines in 2015 to potentially oppose a board member’s reelection for reasons including “insufficient attention to board diversity.” 69 On March 31, 2015, representatives of nine public pension funds with over $1.12 trillion in assets submitted a rulemaking petition to the SEC seeking to require enhanced proxy statement disclosure about the gender, race and ethnicity of board nominees “in order to help us as investors determine whether the board has the appropriate mix to manage risk and avoid groupthink.” 70 Specifically, the funds called for an amendment to Item 407(c)(2)(v) of Regulation S-K not only to require this information but also to require that it be presented, along with other nominee qualifications and skills, by means of a user-friendly chart or matrix. According to the GAO report, SEC officials have indicated that they intend to consider the petition as part of the SEC’s Disclosure Effectiveness Initiative. In response to the GAO report, which was prepared at her request, Representative Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) recently announced plans to introduce legislation that would instruct the SEC to recommend strategies for increasing the representation of women on boards and require that companies report on their policies to encourage the nomination of women for board seats and the proportions of women on their boards and in senior management. For the last two years ISS’s Quick Score 3.0 has included a weighted factor relating to the number of women directors serving on the board, noting that some academic studies have found a correlation between increasing the number of women on boards and better long-term financial performance.

ISS has not indicated a recommended number of women, nor has it made clear how this factor will be weighted in assigning companies a “good” or “bad” governance score. Relevant Experience and Skills Investors increasingly keep a watchful eye on board composition. They expect the mix of board members to cover the waterfront of relevant experience and skills and, in particular, to keep pace with changes in a company’s strategic priorities and challenges. For example, the proposed revisions to CalPERS’ Global Governance Principles advise companies to conduct “routine discussions as part of a rigorous evaluation and succession planning process surrounding director refreshment to ensure boards maintain the necessary mix of skills, diversity and experience to meet strategic objectives.” 71 The types of experience and skills most in demand at present include industry-specific knowledge, digital and social media savvy, global business experience and a deep understanding of cybersecurity or other specific company risks. Concern about the ability of directors to oversee cybersecurity risk, in particular, has reached the national stage.

On December 17, 2015, U.S. Senators Jack Reed (D-RI) and Susan Collins (R-ME) introduced the Cybersecurity Disclosure Act of 2015 with the goal of promoting “transparency in the oversight of cybersecurity risks.” 72 The proposed bipartisan legislation would require the SEC to issue rules requiring public companies to disclose in their Form 10-Ks or annual proxy statements whether any member of the board has expertise or experience in cybersecurity (to be defined by the SEC in coordination with the National Institute of Standards and Technology) and, if not, why the nominating committee believes having this expertise or experience on the board is not necessary because of other cybersecurity steps taken by the company. While the legislation would not require companies to put cyber experts on their boards, it is clearly premised on the belief that “sunlight” will encourage companies (whether on their own initiative or in response to the prodding of better informed investors) to bolster their oversight of cybersecurity. What To Do Now: â— Assess Gaps Relating to Tenure, Independence, Diversity and Skills.

Boards and their nominating committees should take a proactive approach to board composition and succession planning by evaluating the tenure, independence, diversity and skills of the board on a regular basis. Boards should also take a holistic view of a director’s relationships and connections when evaluating independence in the context of related party transactions, particularly given the heightened attention the outside auditor will be paying to documentation of these and “significant unusual transactions”, as well as executive compensation arrangements, in conducting this Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 16 . SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance year’s audit under newly applicable PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 18. Boards also should consider revisiting their age limits and tenure, director refreshment and board self-evaluation policies and procedures. â— Review and Vary Board Evaluation Process. The nominating committee should ensure that the board and key committees are conducting effective self-evaluations that meet evolving standards for robustness.

For companies that have traditionally used questionnaires, consider alternating this methodology with one-on-one discussions with the independent chair/lead independent director/nominating committee chair or an external evaluator. Note that ISS QuickScore 3.0 has been revised to consider whether the board is conducting individual director assessments and to also consider whether an independent outside party is assisting with the board selfassessment process at least once every three years. â— Enhance Proxy Statement Disclosure. Consider using a chart or matrix to make the required information about directors, and possibly additional information about diversity (along with independence and other qualifications, as discussed above), accessible to the reader at a glance.

Investors are looking to see how the experience and other qualifications of each director align with company strategy and key areas of risk. Expect large institutional investors and activist shareholders to continue to demand more information regarding “board refreshment” than the minimum required under the SEC’s current proxy rules. Accordingly, as noted in Part 2 above, companies should give careful thought to how the 2016 proxy statement will address board tenure and other composition and qualification issues, along with the adequacy of the board’s self-evaluation process.

Some companies previously have done this, for example, by explaining the benefits to the company of a particular director’s long service in terms of his or her particular expertise. Spotlight on Disclosure of Voting Standards in Director Elections Director Keith F. Higgins and other senior staff of the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance have sent out the word that more careful attention should be paid to the often-overlooked details of proxy statement disclosure of voting standards governing uncontested elections of directors. After the SEC received rulemaking petitions in early 2015 from each of CII 73 and the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America (the Carpenters) 74 highlighting perceived disclosure deficiencies in corporate proxy materials, the Commission’s Division of Economic and Risk Analysis compiled a random sample of issuers drawn from the Russell 3000 index.

In reviewing the relevant portions of proxy statements and forms of proxy filed this year by issuers in the sample pool, the Division observed several ambiguous, or less than ideal, disclosures similar to those described in the CII and Carpenters petitions, including (but not necessarily limited to) the following: (1) erroneously describing the “plurality plus” voting standard as a “policy on majority voting”; (2) suggesting incorrectly that a “withhold” vote constitutes a vote “against” a director candidate in a plurality voting system; and (3) inconsistencies in descriptions of applicable director election voting standards in the body of the proxy statement vs. the face of the proxy card. 7. Another Key Issue for the Nom/Gov Committee or Full Board: Sustainability Sustainability, broadly defined as the pursuit of a business growth strategy by allocating financial or in-kind resources to ESG practices, is not just a buzzword that boards can address simply through their company’s marketing efforts.

75 Governance activists, institutional investors and regulators 76 are increasingly calling for (and in some cases requiring) companies and their boards to assess and report on the sustainability of their business operations and investments. 77 According to a recent report, the nominating/corporate governance committee is often assigned responsibility for oversight of sustainability issues. 78 Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP January 26, 2016 17 .

SEC Disclosure and Corporate Governance In May 2015, BlackRock teamed up with nonprofit sustainability leader Ceres to create a guide called “21st Century Engagement: Investor Strategies for Incorporating ESG Considerations into Corporate Interactions.” 79 Pension plans have also been vocal in their support for sustainability and responsible investing. CalSTRS has endorsed the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) and worked with the Carbon Disclosure Product and Ceres to improve the transparency and disclosure of environmental risk data by corporations. 80 More than 1,300 institutional investors worldwide, representing $59 trillion in assets under management, have signed on to the UN Principles of Responsible Investing, which seek to integrate ESG concerns into investment objectives. 81 Sustainability Proposals While about 40% of environmental and social shareholder proposals were withdrawn and support for those that made it onto the ballot was far below the majority threshold needed for passage, proposals on social and environmental policy issues comprised the largest category of proposals submitted in 2015 despite the plethora of proxy access proposals.

82 Since 2010, 89 proposals submitted under Rule 14a-8 aimed at annual sustainability reporting appeared in the proxy statements of 58 companies. 83 We expect that the volume of shareholder proposals on environmental and social issues will continue to grow and that they will garner increasing support. In its proxy voting guidelines, ISS recommends that shareholders “generally vote for proposals requesting that a company report on its policies, initiatives and oversight mechanisms related to social, economic, and environmental sustainability.” 84 Glass Lewis’ new proxy voting policy provides that where the board or management has failed to sufficiently identify and manage a material environmental or social risk that either did – or could – negatively impact shareholder value, it will recommend against directors responsible for risk oversight.

85 Sustainability Reporting Public companies in larger numbers are disclosing their efforts to enhance the sustainability of their business practices and building capabilities to report on the environmental and societal impacts of their businesses.86 According to the Governance & Accountability Institute, about 75% of companies in the S&P 500 produced sustainability reports in 2015, is up from 20% in 2011. 87 Companies are also making sustainability-related disclosures in their SEC filings that can be more easily identified and reviewed with a new SEC Sustainability Disclosure Search Tool launched by Ceres in January 2016. 88 In response to investor concerns, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, a nonprofit organization chaired by Michael R.

Bloomberg (the SASB), is writing industry standards for material corporate sustainability and environmental reporting to standardize the way companies report sustainability measures that are useful to investors and can be included in the MD&A. In December 2015, the SASB issued provisional standards for the renewable resources and alternative energy sector to help companies disclose sustainability information that is likely to be material. 89 Also in December 2015, the Financial Stability Board, which coordinates international efforts to develop and promote effective regulatory, supervisory and other financial sector policies in the interest of financial stability, launched a Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, which also will be led by Michael Bloomberg, to make recommendations for consistent company disclosures that will help financial market participants understand their climate-related risks.