Description

Manager of the

TCW, MetWest,

and TCW Alternative

Fund Families

INSIGHT

TRADING SECRETS

If Markets Were Stupid,

Everyone Would Be Rich

TAD RIVELLE | OCTOBER 2015

Tad Rivelle

Group Managing Director

Chief Investment Officer–Fixed Income

Co-Director Fixed Income

Tad Rivelle is Chief Investment Officer, Fixed

Income, overseeing $140 billion in U.S. fixed

income assets, including over $85 billion of

U.S. fixed income mutual fund assets under

the TCW Funds and MetWest Funds brands.

Prior to joining TCW, Tad served as Chief

Investment Officer for MetWest, an independent institutional investment manager

that he cofounded. The MetWest investment

team has been recognized for a number of

performance related awards, including

Morningstar’s Fixed Income Manager of the

Year.

Mr. Rivelle was also the co-director of fixed income at Hotchkis & Wiley and a portfolio manager at PIMCO. Tad holds a BS in Physics from Yale University, an MS in Applied Mathematics from University of Southern California, and an MBA from the UCLA Anderson School of Management. Experienced investors understand that capital markets are information rich, that prices “mean something”, and that “obvious” inefficiencies get arbitraged away.

Yet, rather than listen to markets, the Fed has preferred to talk. Instead of allowing markets to find proper clearing levels, the Fed has insisted that it knows better whether or when to raise rates. Through word and deed, the Fed operates under the belief that a centrally directed monetary regime does a better job of maximizing output, lowering unemployment, and maintaining financial stability than could the capital markets. This conceit is perilous. Economic structures are so vast and so complex that the information required to guide them – or operate them – cannot be reduced to a set of equations within an econometric model.

And, no, it does not matter how many Ph.D. degrees the Fed has, or how well-meaning or intelligent its governors might be. Dynamic and decentralized information with atomized, grass-roots decision-making outwit the computer models and trained experts every time.

Anyone remember the last time the Fed called a recession before it was a recession? The Fed’s version of history for this cycle is a simple tale: the economy cratered as the housing bubble popped. Wrecked balance sheets and depressed animal spirits required repair. Hence, the Fed implemented a zero rate policy.

Trashing cash incentivized risk taking and lowered cap rates. Lowered cap rates drove up asset prices. And raised asset prices – voilà – would unleash a torrent of creditfuelled spending and investing that would raise incomes and bring the economy back to its “potential.” The plan was so obvious, so simple – what could possibly have gone wrong? Plenty.

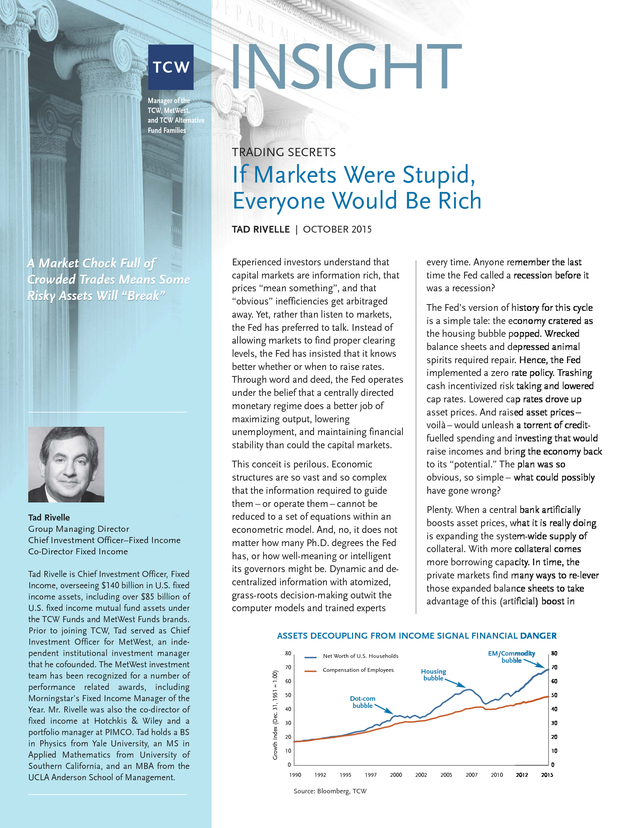

When a central bank artificially boosts asset prices, what it is really doing is expanding the system-wide supply of collateral. With more collateral comes more borrowing capacity. In time, the private markets find many ways to re-lever those expanded balance sheets to take advantage of this (artificial) boost in ASSETS DECOUPLING FROM INCOME SIGNAL FINANCIAL DANGER 80 Growth Index (Dec.

31, 1951 = 1.00) A Market Chock Full of Crowded Trades Means Some Risky Assets Will “Break” 70 Compensation of Employees EM/Commodity bubble Net Worth of U.S. Households 60 50 70 Housing bubble 60 50 Dot-com bubble 40 80 40 30 30 20 20 10 10 0 0 1990 1992 1995 1997 Source: Bloomberg, TCW 2000 2002 2005 2007 2010 2012 2015 . TRADING SECRETS If Markets Were Stupid, Everyone Would Be Rich TAD RIVELLE | OCTOBER 2015 collateral values. Indeed, an expansion of credit was precisely what the Fed said it wanted to see! The fly in the ointment was/is that the Fed cannot control the quality or efficacy of the leverage so engendered by its supposedly pro-growth, pro-credit creation policies. Put simply, if too much credit goes to the wrong places, is used inefficiently or excessively, the result is that the new debt will not be self-financing. deflation to the commodities complex, a sharp slowdown in EM growth rates, a strong dollar and earnings recession to the U.S., and crowded trades in risk assets everywhere. So where does this leave us? Under conditions of de-leveraging, the character of the fixed income market undergoes a sea change of its own. Asset classes self-segregate into three basic cohorts: 1.

Traditional risk-off assets such as Treasuries and agency MBS Central bankers propound the myth that credit creation is good for growth. But credit and debt are one and the same looked at from different sides of the balance sheet. Would anyone seriously suggest that debt accumulation is automatically “good” for an individual or a business? Why, then, should anyone presume that increased leverage is automatically good for a whole society? Debt must be income-producing for it to be “good.” Debt accelerates the process by which resources are put to use, which creates the appearance of growth.

However, if the debt is not self-financing, that appearance is mere illusion. The Fed’s systematic lowering of hurdle rates prioritized the quantity of credit created over the efficiency (quality) of the credit created; hence, the day would surely come when the debt expansion would outrun the capacity to service said debt. Business models predicated on leverage will, at first, experience faster growth.

But should their debt outgrow their revenue, such businesses are forced to downsize, rendering yesterday’s “growth” ephemeral. 2. “Bendable” asset classes such as investment grade corporates, AAA and agency CMBS, and senior non-agency MBS 3. “Breakable” asset classes such as high yield and emerging market debt The distinction between risk-off and risk-on assets is widely understood.

What distinguishes “bendable” assets from “breakable” ones? Bendable assets will experience a “linear” widening in their risk premia while many breakable assets will “gap” to the downside in terms of price. Why does this happen? Simply put, one of the “rules” of capitalism is that if you want to gain control of someone else’s asset, you generally have to pay a multiple of the asset’s future earning power. The “rule” that assets are priced “x times” is ingrained precisely because it is true during the 90% of the business cycle that is characterized by the re-leveraging. However, during a de-leveraging period, certain assets will (rightly or wrongly) be perceived as having no future, i.e., will be re-valued as restructurings and liquidations.

In that event, the valuation paradigm changes from “x times earnings/rent/revenue” to discount to book value or discount to debt. Proponents of stimulus, in whatever form, love to quote the Keynesian phrase, “in the long run, we will all be dead.” While true, such an argument can be used to rationalize all sorts of activities, none of which are healthy long-term choices. “Today” is already the “tomorrow” we were counseled not to fret over back when ZIRP and QE were first implemented. A “breakable” asset is one whose valuation suddenly transitions from “going concern value” to “workout value”. Needless to say, when the market changes its valuation paradigm, the ride down is stomach churning.

In contrast, while bendable assets are priced more cheaply as a de-leveraging unfolds, the inherently solvent nature of bendable assets means they cheapen in a “linear” way as opposed to repricing “catastrophically.” Now more than ever is the time to be wary of owning too much that might be “breakable.” But, wise investing means keeping the long-term perspective, even when all about you may be of the belief that the Fed will keep the credit beast well fed. So, investors must maintain a “full-cycle” perspective that understands that markets sequence through periods of re-leveraging and de-leveraging. These cycles alternate like the tides, and while central bankers can build dams, sea walls, or irrigation channels to “control” the credit markets, investing with the notion that such endeavors can indefinitely prolong an expansion has always proven to be a losing proposition. Alas, the autumn leaves of this cycle have changed color.

Investors need to be prepared for the coming winter of de-leveraging. Now, the Fed’s vast re-leveraging project is running smack dab into that “long run” we were supposed to not fret about. Excesses and misdirection of capital flows have brought oversupply and This material is for general information purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security. TCW, its officers, directors, employees or clients may have positions in securities or investments mentioned in this publication, which positions may change at any time, without notice.

While the information and statistical data contained herein are based on sources believed to be reliable, we do not represent that it is accurate and should not be relied on as such or be the basis for an investment decision. The information contained herein may include preliminary information and/or "forward-looking statements." Due to numerous factors, actual events may differ substantially from those presented. TCW assumes no duty to update any forward-looking statements or opinions in this document.

Any opinions expressed herein are current only as of the time made and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. © 2015 TCW 865 South Figueroa Street | Los Angeles, California 90017 | 213 244 0000 | TCW.com | @TCWGroup 2 .

Mr. Rivelle was also the co-director of fixed income at Hotchkis & Wiley and a portfolio manager at PIMCO. Tad holds a BS in Physics from Yale University, an MS in Applied Mathematics from University of Southern California, and an MBA from the UCLA Anderson School of Management. Experienced investors understand that capital markets are information rich, that prices “mean something”, and that “obvious” inefficiencies get arbitraged away.

Yet, rather than listen to markets, the Fed has preferred to talk. Instead of allowing markets to find proper clearing levels, the Fed has insisted that it knows better whether or when to raise rates. Through word and deed, the Fed operates under the belief that a centrally directed monetary regime does a better job of maximizing output, lowering unemployment, and maintaining financial stability than could the capital markets. This conceit is perilous. Economic structures are so vast and so complex that the information required to guide them – or operate them – cannot be reduced to a set of equations within an econometric model.

And, no, it does not matter how many Ph.D. degrees the Fed has, or how well-meaning or intelligent its governors might be. Dynamic and decentralized information with atomized, grass-roots decision-making outwit the computer models and trained experts every time.

Anyone remember the last time the Fed called a recession before it was a recession? The Fed’s version of history for this cycle is a simple tale: the economy cratered as the housing bubble popped. Wrecked balance sheets and depressed animal spirits required repair. Hence, the Fed implemented a zero rate policy.

Trashing cash incentivized risk taking and lowered cap rates. Lowered cap rates drove up asset prices. And raised asset prices – voilà – would unleash a torrent of creditfuelled spending and investing that would raise incomes and bring the economy back to its “potential.” The plan was so obvious, so simple – what could possibly have gone wrong? Plenty.

When a central bank artificially boosts asset prices, what it is really doing is expanding the system-wide supply of collateral. With more collateral comes more borrowing capacity. In time, the private markets find many ways to re-lever those expanded balance sheets to take advantage of this (artificial) boost in ASSETS DECOUPLING FROM INCOME SIGNAL FINANCIAL DANGER 80 Growth Index (Dec.

31, 1951 = 1.00) A Market Chock Full of Crowded Trades Means Some Risky Assets Will “Break” 70 Compensation of Employees EM/Commodity bubble Net Worth of U.S. Households 60 50 70 Housing bubble 60 50 Dot-com bubble 40 80 40 30 30 20 20 10 10 0 0 1990 1992 1995 1997 Source: Bloomberg, TCW 2000 2002 2005 2007 2010 2012 2015 . TRADING SECRETS If Markets Were Stupid, Everyone Would Be Rich TAD RIVELLE | OCTOBER 2015 collateral values. Indeed, an expansion of credit was precisely what the Fed said it wanted to see! The fly in the ointment was/is that the Fed cannot control the quality or efficacy of the leverage so engendered by its supposedly pro-growth, pro-credit creation policies. Put simply, if too much credit goes to the wrong places, is used inefficiently or excessively, the result is that the new debt will not be self-financing. deflation to the commodities complex, a sharp slowdown in EM growth rates, a strong dollar and earnings recession to the U.S., and crowded trades in risk assets everywhere. So where does this leave us? Under conditions of de-leveraging, the character of the fixed income market undergoes a sea change of its own. Asset classes self-segregate into three basic cohorts: 1.

Traditional risk-off assets such as Treasuries and agency MBS Central bankers propound the myth that credit creation is good for growth. But credit and debt are one and the same looked at from different sides of the balance sheet. Would anyone seriously suggest that debt accumulation is automatically “good” for an individual or a business? Why, then, should anyone presume that increased leverage is automatically good for a whole society? Debt must be income-producing for it to be “good.” Debt accelerates the process by which resources are put to use, which creates the appearance of growth.

However, if the debt is not self-financing, that appearance is mere illusion. The Fed’s systematic lowering of hurdle rates prioritized the quantity of credit created over the efficiency (quality) of the credit created; hence, the day would surely come when the debt expansion would outrun the capacity to service said debt. Business models predicated on leverage will, at first, experience faster growth.

But should their debt outgrow their revenue, such businesses are forced to downsize, rendering yesterday’s “growth” ephemeral. 2. “Bendable” asset classes such as investment grade corporates, AAA and agency CMBS, and senior non-agency MBS 3. “Breakable” asset classes such as high yield and emerging market debt The distinction between risk-off and risk-on assets is widely understood.

What distinguishes “bendable” assets from “breakable” ones? Bendable assets will experience a “linear” widening in their risk premia while many breakable assets will “gap” to the downside in terms of price. Why does this happen? Simply put, one of the “rules” of capitalism is that if you want to gain control of someone else’s asset, you generally have to pay a multiple of the asset’s future earning power. The “rule” that assets are priced “x times” is ingrained precisely because it is true during the 90% of the business cycle that is characterized by the re-leveraging. However, during a de-leveraging period, certain assets will (rightly or wrongly) be perceived as having no future, i.e., will be re-valued as restructurings and liquidations.

In that event, the valuation paradigm changes from “x times earnings/rent/revenue” to discount to book value or discount to debt. Proponents of stimulus, in whatever form, love to quote the Keynesian phrase, “in the long run, we will all be dead.” While true, such an argument can be used to rationalize all sorts of activities, none of which are healthy long-term choices. “Today” is already the “tomorrow” we were counseled not to fret over back when ZIRP and QE were first implemented. A “breakable” asset is one whose valuation suddenly transitions from “going concern value” to “workout value”. Needless to say, when the market changes its valuation paradigm, the ride down is stomach churning.

In contrast, while bendable assets are priced more cheaply as a de-leveraging unfolds, the inherently solvent nature of bendable assets means they cheapen in a “linear” way as opposed to repricing “catastrophically.” Now more than ever is the time to be wary of owning too much that might be “breakable.” But, wise investing means keeping the long-term perspective, even when all about you may be of the belief that the Fed will keep the credit beast well fed. So, investors must maintain a “full-cycle” perspective that understands that markets sequence through periods of re-leveraging and de-leveraging. These cycles alternate like the tides, and while central bankers can build dams, sea walls, or irrigation channels to “control” the credit markets, investing with the notion that such endeavors can indefinitely prolong an expansion has always proven to be a losing proposition. Alas, the autumn leaves of this cycle have changed color.

Investors need to be prepared for the coming winter of de-leveraging. Now, the Fed’s vast re-leveraging project is running smack dab into that “long run” we were supposed to not fret about. Excesses and misdirection of capital flows have brought oversupply and This material is for general information purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security. TCW, its officers, directors, employees or clients may have positions in securities or investments mentioned in this publication, which positions may change at any time, without notice.

While the information and statistical data contained herein are based on sources believed to be reliable, we do not represent that it is accurate and should not be relied on as such or be the basis for an investment decision. The information contained herein may include preliminary information and/or "forward-looking statements." Due to numerous factors, actual events may differ substantially from those presented. TCW assumes no duty to update any forward-looking statements or opinions in this document.

Any opinions expressed herein are current only as of the time made and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. © 2015 TCW 865 South Figueroa Street | Los Angeles, California 90017 | 213 244 0000 | TCW.com | @TCWGroup 2 .