Improving Outcomes with Electronic Delivery of Retirement Plan Documents - June 2015

SPARK Institute

Description

Improving Outcomes with

Electronic Delivery of

Retirement Plan

Documents

Prepared for

The SPARK Institute

June, 2015

i

. Improving Outcomes with Electronic Delivery of

Retirement Plan Documents

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................1

I.

Restrictive Framework Guiding Electronic Delivery ..................................................3

A.

B.

C.

II.

Conducting Financial Business Online .......................................................................11

A.

B.

III.

Use of Electronic Methods in Financial Transactions ...................................11

Efficiencies and Cost Savings...........................................................................14

1.

Efficiencies .............................................................................................14

2.

Cost Savings...........................................................................................16

3.

Electronic Delivery Benefits Participants ...........................................17

Improving Participant Outcomes through Electronic Delivery ...............................19

A.

B.

C.

IV.

Overview ..............................................................................................................3

DOL and IRS Electronic Delivery Regulations................................................5

1.

DOL’s Electronic Disclosure Safe Harbor ...........................................6

2.

DOL’s Interpretive and Technical Guidance .......................................7

3.

IRS’s Media Disclosure Guidance .........................................................7

Online Access Offers the Potential to Expand Electronic Delivery ...............8

Attitudes toward Electronic Delivery of Plan Information...........................19

Enhancing Retirement Savings through Electronic Delivery ......................20

Automatic Features with Opt Out Improves Outcomes ...............................22

1.

Auto Enrollment Increases Participation and Deferral Rates ..........23

2.

Increasing the Power of Default Rules ...............................................24

CONCLUSION .............................................................................................................25

APPENDIX A – PLAN PARTICIPANT VIEWS ON PAPER VERSUS ELECTRONIC

DELIVERY OF PLAN DOCUMENTS ......................................................................26

APPENDIX B – TECHNICAL DESCRIPTION OF COST SAVINGS ..............................40

REFERENCES ..........................................................................................................................46

i

. LIST OF TABLES

Table 1

Disclosure Requirements and Electronic Delivery Options .......................................5

FIGURES

Figure 1 Some employers would like to automatically provide employees retirement plan

information by e-mail or through continuously available secure website ................19

Figure 2 Some retirement plans offer tools or calculators that allow you to compute such

things as how good a job you are doing in preparing for retirement ........................20

Figure 3 Benefits Accruing to Participants .............................................................................41

LIST OF GRAPHS

Graph 1 Availability of Computers and Internet Access in the Home, Percentage of

Households, Selected Years ........................................................................................8

Graph 2 Internet and Computer Access by Employment Status, 2013.....................................9

Graph 3 Computer and Internet Access at Home, by Age ......................................................10

Graph 4 Preferred Banking Method, All Customers .............................................................12

Graph 5 Preferred Banking Method, Customers Age 55 Years or Older ...............................12

Graph 6 Electronic Payment Rates for Social Security and Supplemental Security Income

Payments, 1996 through 2014...................................................................................13

Graph 7 Percent of Individual Income Tax Returns Filed Electronically,

2001 through 2014 ....................................................................................................14

Graph 8 Average Deferral Rates for Plan Participants, by Age and Electronic

Delivery Status ..........................................................................................................21

Graph 9 Average Deferral Rates for Plan Participants, by Age and Electronic

Delivery Status ..........................................................................................................21

Graph 10 Average Account Balance by Electronic Delivery Status, by Participant Age ........22

Graph 11 Participation Rates among Automatic Deferral Options ..........................................24

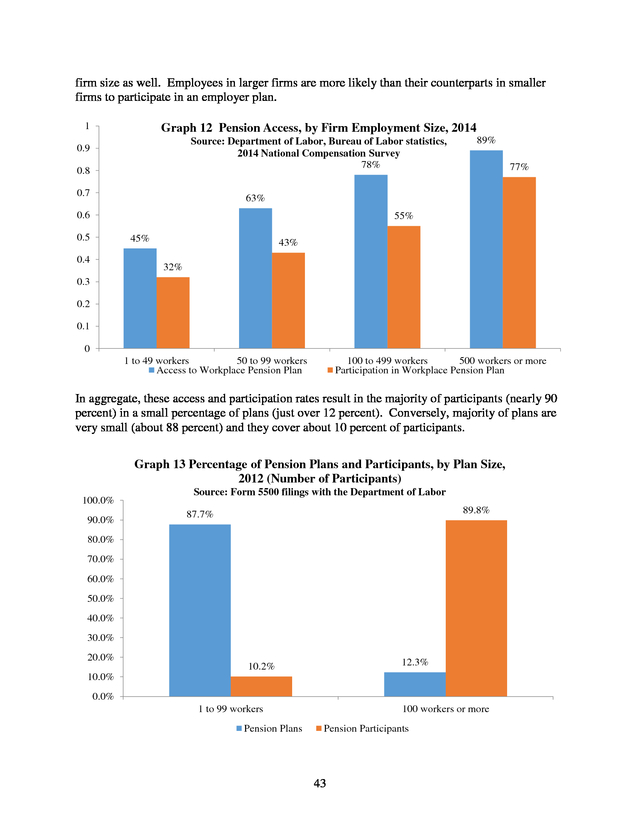

Graph 12 Pension Access, by Firm Employment Size, 2014 ...................................................42

Graph 13 Percentage of Pension Plans and Participants, by Plan Size, 2012...........................42

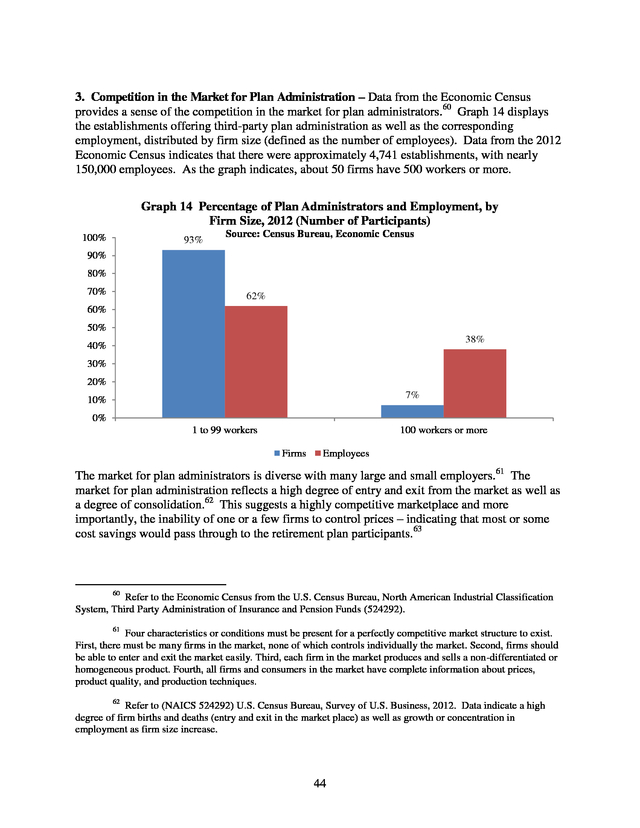

Graph 14 Percentage of Plan Administrators and Employment, by Firm Size, 2012 ..............43

ii

. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Employers that voluntarily choose to offer defined contribution retirement plans, such as 401(k) plans, are

required to distribute numerous statements and disclosures both quarterly and annually. Many plans

would like, as a default, to distribute retirement plan information electronically. All participants would be

given the right to “opt out” and receive paper communications at no charge.

But current rules stand in the way. The Department of Labor (DOL) and Internal Revenue Service (IRS)

have issued extensive guidance governing the manner in which plans can distribute retirement plan

information electronically.

But depending on the nature of the information, any one of four different IRS or DOL standards can apply. In some contexts, plans can default participants into electronic delivery; for other information it is necessary to sign up each participant for electronic delivery – which entails a formidable battle against inertia. Lack of consistency causes considerable confusion for retirement plan administrators and their participants alike. Today’s highly restrictive framework guiding electronic delivery of plan information is trapped in the Twentieth Century; this framework reflects neither recent years’ emerging information trends and technologies nor these trends and technologies’ many benefits – for both participants and plan administrators.

Yet as reported in a Greenwald & Associates survey, plan participants are aware of the many potential benefits of electronic delivery and they overwhelmingly find it acceptable to make electronic delivery the default method of delivering of plan information. Besides reducing costs (with savings significantly passed through to plan participants), electronic delivery provides an efficient and reliable means of communicating important plan information, which facilitates superior participant outcomes. This White Paper examines the many rationale for allowing plan sponsors to make electronic delivery the default method for communicating with retirement plan participants. Findings  Online Access Offers the Potential to Expand Electronic Delivery – Recent surveys indicate that virtually all Americans have access to online services, in the workplace and/or at home. Access is broad across age group, race, household income, and region.  Conducting Financial Business Online – Alongside dramatic growth in computer and Internet use, so too has Americans’ reliance on electronic technology for financial communication and transactions grown significantly.

This growth has taken place in areas of critical importance to everyday life:    Banking and Financial Transactions – Online and mobile phone banking is fast becoming the preferred banking method across all age groups. Social Security Benefits – Nearly all Social Security recipients (98.6 percent in 2014) receive their benefits through electronic payment. Federal Income Tax Filing – The trend to file individual tax returns electronically continues to experience steady growth. Specifically, 85 percent of the 137 million returns filed as of May 16, 2014 were filed electronically. Since conducting day-to-day financial transactions online serves as a proxy for a retirement plan participant’s willingness to receive electronically plan-related notices, disclosures, and statements, the move toward conducting day-to-day financial transactions is a strong indicator that participants would prefer and benefit from electronic delivery of plan information. 1 .  Benefits of Electronic Delivery – Relying on paper communication is both inefficient and costly. Even the federal government has recognized in its defined contribution plan for federal employees that electronic delivery of plan information is the appropriate default. Electronic delivery:      Allows participants to respond quickly to plan information received electronically; Ensures information remains up-to-date and is accessed by participants in “real time;” Provides information that is more accessible – and digestible; Provides information that can be more readily customized; and Provides a better guarantee of actual receipt of information.  Cost Savings – Compared to distributing plan documents by mail, electronic delivery has significantly lower costs, with savings from printing, processing, and mailing. A recent study estimates that moving from paper to electronic delivery of certain documents could reduce costs of producing communications by 36 percent.  Benefits Accruing to Participants – Allowing retirement plan administrators to make electronic delivery a default would reduce the costs associated with their plans. As our research based on economic incidence theory shows, these cost savings would ultimately be passed back to participants, translating to lower expenses – and higher net investment returns – for participants.

We calculate that switching to an electronic delivery default would produce $200 to $500 million in aggregate savings annually that would accrue directly to individual retirement plan participants.  Attitudes Toward Electronic Delivery – Despite the changing attitudes toward electronic mediums in all aspects of daily life, the current rules have inhibited plans from adopting “opt-out” electronic delivery practice for retirement plan documents. Yet in a poll of retirement plan participants, 84 percent find it acceptable to make electronic delivery the default option (with the ability to opt out without cost).  Enhancing Retirement Savings with Electronic Delivery – Directing participants to electronic mediums promotes the use of electronic tools (such as retirement readiness calculators) that ultimately play an important role in promoting superior retirement outcomes. In fact, as provider data demonstrate, mere exposure to online tools has been shown to encourage participants to increase deferrals or modify their investment strategy to achieve a secure retirement.

Consequently, participants that receive plan communications electronically have better retirement outcomes.  Default Rules that Rely on Opt-Out Improve Outcomes – Behavioral economists have demonstrated the importance of setting the appropriate default rule in engaging individuals. Accordingly, in the landmark Pension Protection Act of 2006, Congress promoted the use of “automatic” rules that facilitate “automatic” behavior. The evidence is clear that this shift has had a critical impact on driving superior outcomes:   Auto Enrollment Increases Participation and Deferral Rates – Recent surveys indicates that using an opt-out provision increased retirement plan participation rates, from 49 without automatic enrollment to 91 percent with automatic enrollment; and Automatic escalation of deferral rates and automatic investment defaults –One recent survey found that automatic escalation of contribution amounts increased plan deferral rates by 21 percent and the increased contributions resulted in average account balance growth of 78 percent for plans with automatic contribution escalation. 2 . I. A. Restrictive Framework Guiding Electronic Delivery Overview Federal law (both the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 [ERISA] and the Internal Revenue Code [Code], and the regulations thereunder) requires that qualified retirement plan participants receive plan information on a regular basis. This breadth of required information, as outlined in Table 1, includes plan description and summary materials, benefit statements, and disclosures regarding expenses and fees. Traditionally, retirement plans (through their administrators) have prepared printed (hard) copies of these materials for distribution to employees and other plan participants (including former employees who have already retired).1 This has entailed either distributing materials to employees at the workplace or, in many cases, mailing the materials to participants. But as electronic communication has gained traction as the primary means by which individuals receive important information, retirement plans have increasingly turned to delivering information through e-mail or secure websites.2 Besides reducing costs (which are passed through to plan participants), electronic delivery of plan information provides an efficient and reliable means of communicating important plan information – which can facilitate superior participant outcomes. Rules issued by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) govern the distribution of plan information by electronic means.

While providing some guidance for retirement plans, these rules generally do not permit plan administrators to make electronic delivery the default delivery option. Rather, current DOL and IRS guidance often requires that a plan participant affirmatively consent to receive electronic delivery of plan information. But as behavioral economics, particularly in the retirement plan context, has made clear, inertia is an exceedingly powerful force.

The need for affirmative consent creates a considerable barrier for plans trying to increase efficiencies and pass those efficiencies to plan participants – even while (as Section II.B. shows) the overwhelming majority of today’s plan participants are comfortable with an electronic default that enables them to “opt out” for paper. Further, the existing DOL and IRS rules apply different electronic delivery standards to different communications; the conflicting standards create considerable confusion for plans. Indeed, today’s highly restrictive framework guiding electronic delivery of plan information is trapped in the Twentieth Century; this framework reflects neither recent years’ emerging information trends and technologies nor these trends and technologies’ many benefits for retirement plan participants. 1 Plan administrators include employers who sponsor a qualified retirement plan, plan trustees, or thirdparty managers who act as a plan fiduciary and are responsible for the plan’s administration and management. 2 Use of traditional first-class mail (single piece and bulk mailing) service via the U.S.

Postal Service has declined 32.8 percent since 2004. This decline is linked to the widespread use of electronic communication. Refer to U.S.

Postal Service, Postal Facts, 2014, A Decade of Facts and Figures, available online: http://about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-facts/decade-of-facts-and-figures.htm. 3 . Given these many benefits of electronic delivery, it is not surprising that plan participants themselves are overwhelmingly willing to accept electronic communication and online access for retirement plan information. As a recent telephone survey conducted by Greenwald & Associates found, 84 percent of plan participants find it acceptable to make electronic delivery the default option (with the option to opt-out at no cost to the participant).3 The importance of these results cannot be overstated. First, the results are current, reflecting views of plan participants interviewed through January 2015. Second, this timely survey of plan participants is consistent with the many trends toward Internet access and daily use of the Internet.

The surveyed plan participants reflect (1) the current trends toward online access and electronic communication in their day-to-day activities as well as (2) a number of efficiencies that would accrue from moving to electronic delivery of plan information. The Greenwald survey results indicate that participants recognize clearly the many benefits available from moving to electronic delivery. Consistent with plan participant views, recent legislative efforts recognize the importance of allowing plan administrators to keep pace with these trends (outlined in Section II.A.) to facilitate more widespread delivery of plan information through electronic methods. Among these is Congressman Richard Neal (D-MA)’s Retirement Plan Simplification and Enhancement Act of 2012, which would allow administrators to deliver all ERISA and Tax Code notices electronically, as long as the plan meets uniform DOL requirements.4 Meanwhile, Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT)’s Secure Annuities for Employee Retirement Act of 2013 would allow default electronic delivery of all plan-related notices in accordance with any of the existing DOL or IRS standards.5 While making electronic delivery the default delivery method, both legislative proposals would preserve the opportunity for a participant to opt-out of electronic and request, at no charge, paper copies of any document.

These legislative proposals are consistent with a number of Executive Orders that President Obama has issued to Federal Agencies, directing them to conduct electronic transactions whenever feasible.6 By enabling plans to set electronic delivery as the default delivery method, considerable benefits would accrue to plan participants, not only from reduced costs, but also from increased efficiencies (through access to online tools and 3 The study examines plan participant views toward receiving plan documents and account updates by paper and online. A total of 1,000 randomly selected plan participants nationwide were administered a 10-minute telephone survey. The results reflect the weighted (by age and gender) responses to reflect the current demographics of plan participants.

Refer to Appendix A for the complete Greenwald & Associates survey. 4 112th Cong., H.R. 4050, § 402. The bill would require plan administrators to meet conditions that have already been established by the DOL for certain communications, i.e., continuous secure website access, with instructions and notifications to participants of their ability to opt-out of electronic delivery (and receive paper copies) at no cost to the participant.

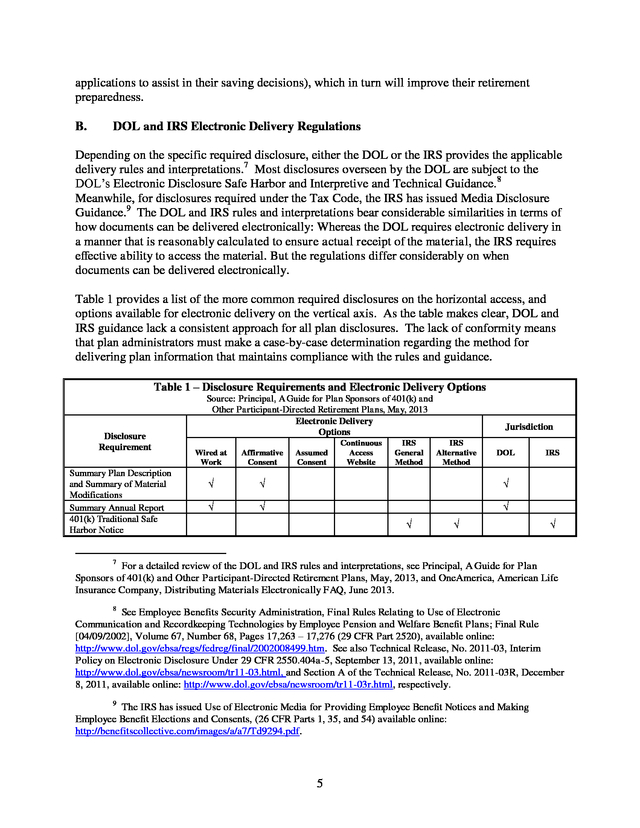

The bill would require plan participants to receive annually these instructions and notifications. 5 113th Cong., S.1270, § 241. 6 Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President, Reducing Reporting and Paperwork Burdens, Memo dated June 22, 2012. 4 . applications to assist in their saving decisions), which in turn will improve their retirement preparedness. B. DOL and IRS Electronic Delivery Regulations Depending on the specific required disclosure, either the DOL or the IRS provides the applicable delivery rules and interpretations.7 Most disclosures overseen by the DOL are subject to the DOL’s Electronic Disclosure Safe Harbor and Interpretive and Technical Guidance.8 Meanwhile, for disclosures required under the Tax Code, the IRS has issued Media Disclosure Guidance.9 The DOL and IRS rules and interpretations bear considerable similarities in terms of how documents can be delivered electronically: Whereas the DOL requires electronic delivery in a manner that is reasonably calculated to ensure actual receipt of the material, the IRS requires effective ability to access the material. But the regulations differ considerably on when documents can be delivered electronically. Table 1 provides a list of the more common required disclosures on the horizontal access, and options available for electronic delivery on the vertical axis. As the table makes clear, DOL and IRS guidance lack a consistent approach for all plan disclosures. The lack of conformity means that plan administrators must make a case-by-case determination regarding the method for delivering plan information that maintains compliance with the rules and guidance. Table 1 – Disclosure Requirements and Electronic Delivery Options Disclosure Requirement Summary Plan Description and Summary of Material Modifications Summary Annual Report 401(k) Traditional Safe Harbor Notice Source: Principal, A Guide for Plan Sponsors of 401(k) and Other Participant-Directed Retirement Plans, May, 2013 Electronic Delivery Options Assumed Consent Continuous Access Website IRS General Method Jurisdiction IRS Alternative Method Wired at Work Affirmative Consent √ √ √ √ √ √ √ DOL √ IRS √ 7 For a detailed review of the DOL and IRS rules and interpretations, see Principal, A Guide for Plan Sponsors of 401(k) and Other Participant-Directed Retirement Plans, May, 2013, and OneAmerica, American Life Insurance Company, Distributing Materials Electronically FAQ, June 2013. 8 See Employee Benefits Security Administration, Final Rules Relating to Use of Electronic Communication and Recordkeeping Technologies by Employee Pension and Welfare Benefit Plans; Final Rule [04/09/2002], Volume 67, Number 68, Pages 17,263 – 17,276 (29 CFR Part 2520), available online: http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/regs/fedreg/final/2002008499.htm.

See also Technical Release, No. 2011-03, Interim Policy on Electronic Disclosure Under 29 CFR 2550.404a-5, September 13, 2011, available online: http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/newsroom/tr11-03.html, and Section A of the Technical Release, No. 2011-03R, December 8, 2011, available online: http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/newsroom/tr11-03r.html, respectively. 9 The IRS has issued Use of Electronic Media for Providing Employee Benefit Notices and Making Employee Benefit Elections and Consents, (26 CFR Parts 1, 35, and 54) available online: http://benefitscollective.com/images/a/a7/Td9294.pdf. 5 .

Table 1 – Disclosure Requirements and Electronic Delivery Options Disclosure Requirement Quarterly Benefit Statement Plan and Expense Information for ParticipantDirected Plans Investment Information for Participant-Directed Plans (in tabular or other accessible format) Automatic Enrollment and Qualified Default Investment Alternative Notices Blackout Notices IRS Notices (for example, Rollover Notices or Qualified Domestic Relations Orders) Source: Principal, A Guide for Plan Sponsors of 401(k) and Other Participant-Directed Retirement Plans, May, 2013 Electronic Delivery Options Wired at Work Affirmative Consent Assumed Consent √ √ √ √ √ √ √ IRS Alternative Method √ √ IRS General Method √ √ Continuous Access Website Jurisdiction √ IRS √ √ DOL √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ Reviewing this existing panoply of electronic delivery rules, a recent Government Accountability Office (GAO) report concluded that the current framework is “somewhat inconsistent and unclear.”10 The GAO found a need to clarify the rules and disclosure guidance between the DOL and IRS to avoid inconsistencies. As the following descriptions of the DOL and IRS guidance shows, this inconsistent framework complicates the process for making the many required disclosures. 1. DOL’s Electronic Disclosure Safe Harbor – A fiduciary (in this case generally the plan administrator) that complies with the safe harbor is treated as having delivered the materials by traditional postal service. To satisfy the safe harbor, the plan must ensure that the electronic systems:       Guarantee receipt of the materials; Protect confidentiality of personal information; Deliver notices explaining the importance of the materials and the option to “optout” of electronic delivery; Contain materials that are easily understood and accessible to the participant; Contain the same content as documents delivered by other means; and Respond accordingly to requests for paper documents. The safe harbor identifies participants who (in popular parlance) are “wired at work” or who given their “affirmative consent” as having the potential to receive information electronically. 10 See Government Accountability Office, Private Pensions Revised Electronic Disclosure Rules Could Clarify Use and Better Protect Participant Choice, GAO-13-594, September 2013. 6 .

An employee who is wired at work requires has access to electronic materials at any location where the employee works and use of the computer is an integral part of the employee’s work duties. Affirmative consent requires that the plan communicate the:     Types of document covered by consent; Ability to withdraw consent at any time, without cost; Procedures for withdrawing consent; and Hardware and software requirements necessary to access and store the electronic documents. 2. DOL’s Interpretive and Technical Guidance (for benefit statements) – Separate from its generally applicable safe harbor, DOL provides a separate set of rules for delivery of quarterly benefit statements. Plans may make quarterly benefit statements available through “one or more secure continuous access websites.” But to deliver quarterly statements this way, plans must provide an annual notice explaining the: (1) availability of the information on the website; (2) instructions for accessing the information; and (3) right to request paper copies at no additional cost. Participants who meet the “wired at work” or “affirmative consent” requirements can be electronically provided this annual notice regarding; otherwise, the notice must be sent via traditional postal service.11 Additionally, in the context of plan and expense information and, for participant-directed plans, investment information, DOL issued additional information regarding the “assumed consent” method for electronic delivery.

Specifically, the plan may treat a participant as having provided his or her consent if the participant (1) receives an annual notice consistent with the requirements under “affirmative consent” and then (2) provides an e-mail address to the administrator for electronic delivery. Moreover, the plan must continue to provide annual notices conveying the same information (as that contained in the initial notice). 3. IRS’s Media Disclosure Guidance – The IRS has two methods governing the default use of electronic delivery, its “general” and “alternative” methods.

The general method parallels the DOL’s Electronic Disclosure Safe Harbor, which requires affirmative consent. The alternative method provides greater flexibility for the plan, allowing delivery of information through any electronic medium (e.g., e-mail or continual access website) as long as the individual has the “effective ability to access” the materials. In addition, the administrator must advise recipients – at the time of electronic delivery – that they have the right to request paper copies without any associated costs. Some call this the “post and push” method of delivery. 11 Even if a plan administrator must send notices by mail, the participant may still also receive quarterly benefit statements through online access. 7 .

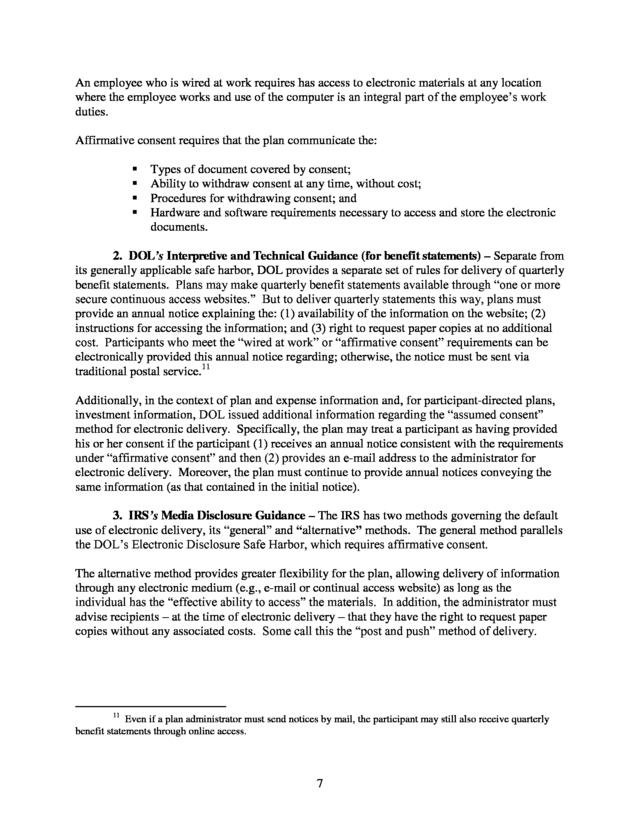

C. Online Access Offers the Potential to Expand Electronic Delivery Graph 1 Availability of Computers and Internet Access in 88% 79% Percent of Households the Home, Percentage of Households, Selected Years Allowing plan administrators to send Source: U.S. Census Bureau 90% electronically, by default, all ERISA and Tax Code notices, disclosures, and 77% 76% 80% 74% statements is compatible with 70% widespread Internet access for the vast 70% 72% 62% 71% majority of active, separated, and 69% 12 56% 60% retired plan participants. Indeed, 62% 51% recent private- and public-sector 50% 55% surveys indicate that virtually all 50% Americans have access to online 37% 40% 42% services, either in the workplace or at 30% home. These surveys confirm both that workplace access is widespread across 20% sectors, and that the overwhelming 18% majority of Americans have computers 10% 1997 2000 2001 2003 2007 2009 2010 2011 and Internet access in their homes.13 Internet at Home Computer at Home Further, the Greenwald survey of retirement plan participants’ online habits indicate that 99 percent reported having access at home or work and 88 percent of respondents reported accessing the Internet on a daily basis.14 2013 Workplace Access – Research on workplace Internet access finds a clear relationship between the location of a job and the likelihood that an employee has access to the Internet at work. Assessing the extent to which broadband access was present in the workplace,15 a recent National Telecommunications and Information Agency (NTIA) statistical analysis found a strong relationship between where employers tend to locate and workplace access to the Internet.16 In other words, the vast majority of employment tends to concentrate around certain geographic 12 Under this option, the plan administrator must meet the conditions established by the DOL, i.e., continuous secure website access, with instructions and notifications of the ability to opt-out at no cost to the participant.

The plan participant must receive annually these instructions and notifications. 13 Duggan, Maeve and Aaron Smith, Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project, Cell Internet Use, September 16, 2013 (data from the Pew tracking survey, July 18 through September 30, 2013). While younger respondents (age 18 to 29 years) reported the highest rates of daily use (88 percent), respondents age 65 years or older also reported significant rates (71 percent). 14 Refer to Appendix A for the complete Greenwald & Associates survey. 15 The NTIA matched statistical data from the broadband availability survey with Census block data from the Longitudinal Employer-Household Origin-Destination Employment Statistics. Refer to NTIA, Broadband Availability in the Workplace, Broadband Brief No.

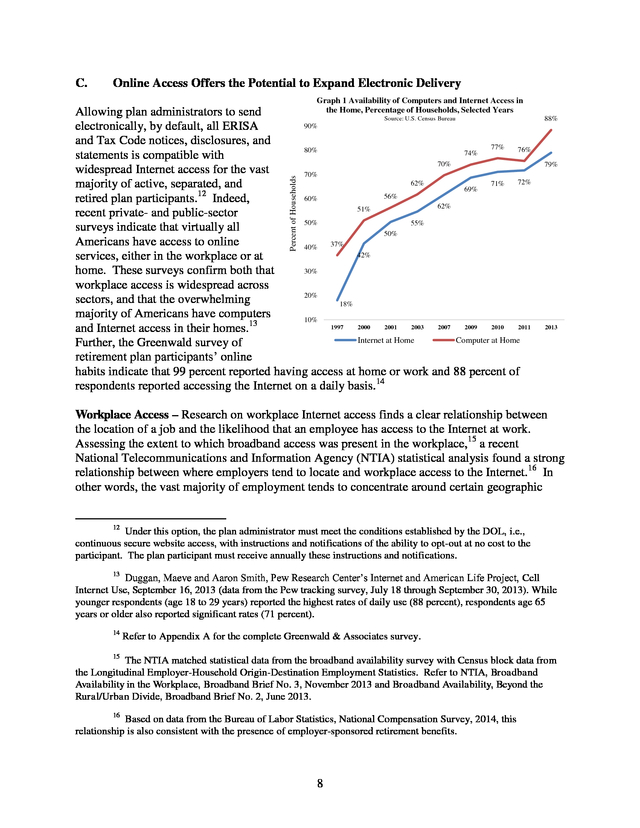

3, November 2013 and Broadband Availability, Beyond the Rural/Urban Divide, Broadband Brief No. 2, June 2013. 16 Based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey, 2014, this relationship is also consistent with the presence of employer-sponsored retirement benefits. 8 . regions of that state (generally population centers). The NTIA found Internet access was widely available in these geographic regions. Graph 2 Internet and Computer Access by Employment Status, 2013 Source: U.S. Census Bureau 100% 93% Percent of Households 90% 87% 84% 78% 74% 80% 70% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Employed Internet at Home Unemployed Not in the Civilian Labor Force While finding some variation in the speed of access, NTIA reports that “virtually all jobs in the United States are located in areas with at least basic wired or wireless broadband service availability….”17 Only employees in “very rural” regions (defined as 11 or fewer residents per square mile) faced limited high-speed Internet access, but just 5.3 percent of U.S. employees work in these very rural regions.

Thus, the overwhelming majority of the workforce has workplace access to high-speed Internet services. Computer at Home Households with Home Access – Over the past twenty years, household access to computers and Internet connections has increased dramatically. (Refer to Graph 1.) According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 1997 fewer than half of all households had computers at home.

By 2013, 88.4 percent of all households had computers at home, and 79 percent had Internet access in their home.18 These high access rates are generally consistent across household employment status. As Graph 2 reflects, the vast majority of Americans who are employed, unemployed, and not currently in the civilian workforce have both computer and Internet access in their home.19 Internet and Computer Access by Age – Some assume that older Americans (those at retirement age) lack Internet access. But this assumption belies reality.

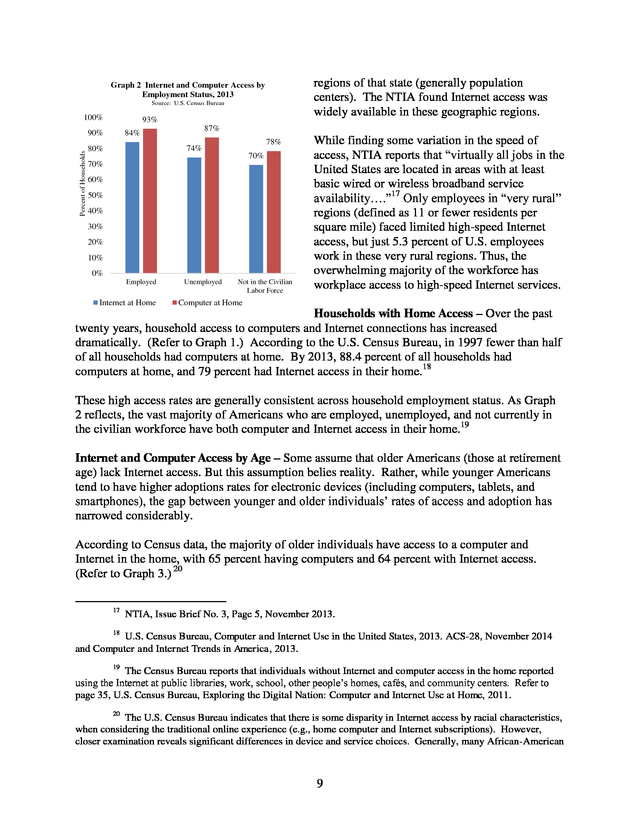

Rather, while younger Americans tend to have higher adoptions rates for electronic devices (including computers, tablets, and smartphones), the gap between younger and older individuals’ rates of access and adoption has narrowed considerably. According to Census data, the majority of older individuals have access to a computer and Internet in the home, with 65 percent having computers and 64 percent with Internet access. (Refer to Graph 3.) 20 17 NTIA, Issue Brief No. 3, Page 5, November 2013. 18 U.S. Census Bureau, Computer and Internet Use in the United States, 2013.

ACS-28, November 2014 and Computer and Internet Trends in America, 2013. 19 The Census Bureau reports that individuals without Internet and computer access in the home reported using the Internet at public libraries, work, school, other people’s homes, cafés, and community centers. Refer to page 35, U.S. Census Bureau, Exploring the Digital Nation: Computer and Internet Use at Home, 2011. 20 The U.S.

Census Bureau indicates that there is some disparity in Internet access by racial characteristics, when considering the traditional online experience (e.g., home computer and Internet subscriptions). However, closer examination reveals significant differences in device and service choices. Generally, many African-American 9 .

Graph 3 Computer and Intenet Access at Home, by Age Source: U.S. Census Bureau, ACS-28, November 2014 100% 93% 92% 90% 81% 87% 83% 81% Percent of Households 80% 70% 65% 64% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 15 to 34 years 35 to 44 years 45 to 64 years Computer in the Home 65 years or older Internet in the Home Internet Access Beyond Computers – Alongside enhancements to computer access, there has been a considerable change in the available technology. Smaller, hand-held devices (including smartphones and tablets) now contain Internet browsers that enable users to have Internet access comparable to those with home computers. According to the Census Bureau, in 2011, 48.2 percent of individuals used a smartphone to access the Internet, for a variety of reported uses.21 Other more recent surveys suggest that this number is increasing, with 63 percent of cellphone owners using their device to access the Internet.22 Plan participants surveyed in the Greenwald & Associates found that 80 percent reported using an Internet browser on their smartphone or tablet.23 and Hispanic households choose smartphone service over home computers and Internet subscriptions.

Refer to the U.S. Census Bureau, Computer and Internet Use in the United States, 2013. P20-569, May 2013. 21 Ibid.

Respondents reported that in addition to making phone calls, activities included web browsing, email access, maps, games, social networking, as well as entertainment (music, photos, and video). 22 Duggan, Maeve and Aaron Smith, Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project, Cell Internet Use, September 16, 2013. 23 Refer to Appendix A for the complete Greenwald & Associates survey. 10 . II. Conducting Financial Business Online Alongside this dramatic growth in computer and Internet use over the past twenty years, so too has Americans’ reliance on electronic technology for financial communication and transactions grown significantly. This growth has taken place across areas of critical importance to everyday life, including payment processing (payroll and Social Security benefit payments), income tax reporting and refund payments, banking and investment financial transactions, and financial information distribution. In fact, electronic communication and transactions are now the overwhelming standard for most American households. For example, within the private sector, businesses routinely use electronic payments for payroll processing. One large payroll processing firms reported having processed electronically $1.5 trillion in direct deposit, client tax payments, and related funds in fiscal year 2014.24 Even the Federal government itself has followed this trend, using electronic delivery to pay benefits to 98.6 percent of Social Security recipients.

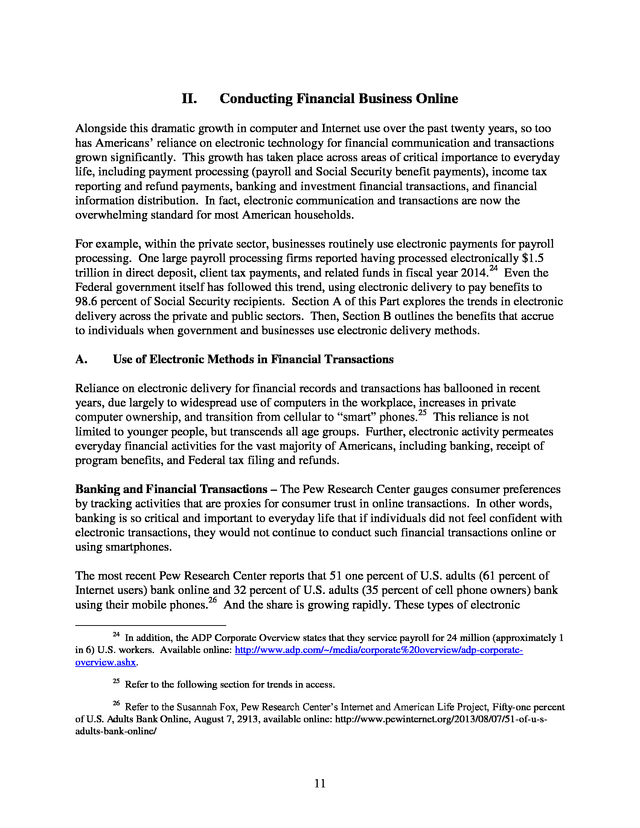

Section A of this Part explores the trends in electronic delivery across the private and public sectors. Then, Section B outlines the benefits that accrue to individuals when government and businesses use electronic delivery methods. A. Use of Electronic Methods in Financial Transactions Reliance on electronic delivery for financial records and transactions has ballooned in recent years, due largely to widespread use of computers in the workplace, increases in private computer ownership, and transition from cellular to “smart” phones.25 This reliance is not limited to younger people, but transcends all age groups. Further, electronic activity permeates everyday financial activities for the vast majority of Americans, including banking, receipt of program benefits, and Federal tax filing and refunds. Banking and Financial Transactions – The Pew Research Center gauges consumer preferences by tracking activities that are proxies for consumer trust in online transactions.

In other words, banking is so critical and important to everyday life that if individuals did not feel confident with electronic transactions, they would not continue to conduct such financial transactions online or using smartphones. The most recent Pew Research Center reports that 51 one percent of U.S. adults (61 percent of Internet users) bank online and 32 percent of U.S. adults (35 percent of cell phone owners) bank using their mobile phones.26 And the share is growing rapidly.

These types of electronic 24 In addition, the ADP Corporate Overview states that they service payroll for 24 million (approximately 1 in 6) U.S. workers. Available online: http://www.adp.com/~/media/corporate%20overview/adp-corporateoverview.ashx. 25 Refer to the following section for trends in access. 26 Refer to the Susannah Fox, Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project, Fifty-one percent of U.S.

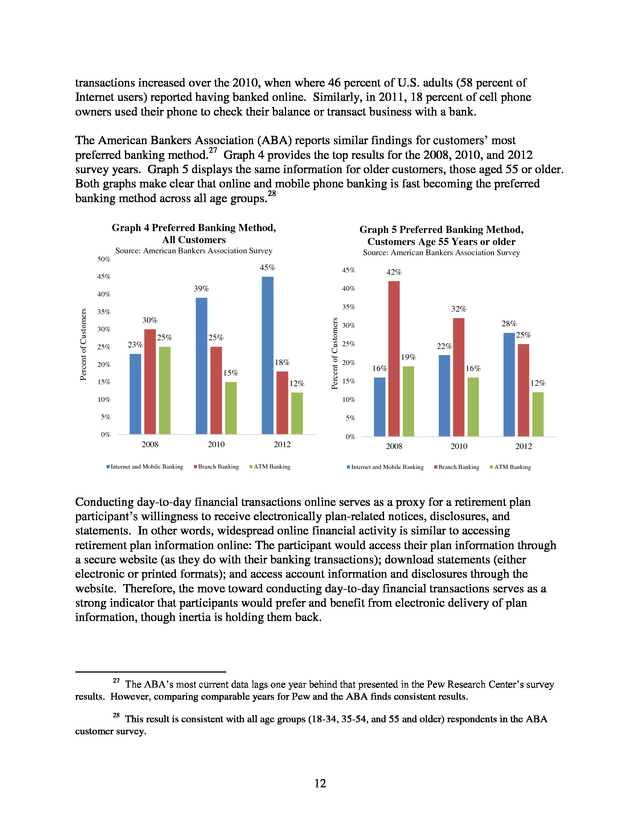

Adults Bank Online, August 7, 2913, available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/08/07/51-of-u-sadults-bank-online/ 11 . transactions increased over the 2010, when where 46 percent of U.S. adults (58 percent of Internet users) reported having banked online. Similarly, in 2011, 18 percent of cell phone owners used their phone to check their balance or transact business with a bank. The American Bankers Association (ABA) reports similar findings for customers’ most preferred banking method.27 Graph 4 provides the top results for the 2008, 2010, and 2012 survey years. Graph 5 displays the same information for older customers, those aged 55 or older. Both graphs make clear that online and mobile phone banking is fast becoming the preferred banking method across all age groups.28 Graph 4 Preferred Banking Method, All Customers Graph 5 Preferred Banking Method, Customers Age 55 Years or older Source: American Bankers Association Survey Source: American Bankers Association Survey 50% 45% 45% 45% 39% 40% 35% 35% 30% Percent of Customers Percent of Customers 40% 42% 30% 23% 25% 25% 25% 18% 20% 15% 15% 12% 32% 28% 25% 30% 25% 20% 22% 19% 16% 16% 15% 10% 10% 5% 12% 5% 0% 0% 2008 Internet and Mobile Banking 2010 Branch Banking 2012 2008 ATM Banking Internet and Mobile Banking 2010 Branch Banking 2012 ATM Banking Conducting day-to-day financial transactions online serves as a proxy for a retirement plan participant’s willingness to receive electronically plan-related notices, disclosures, and statements.

In other words, widespread online financial activity is similar to accessing retirement plan information online: The participant would access their plan information through a secure website (as they do with their banking transactions); download statements (either electronic or printed formats); and access account information and disclosures through the website. Therefore, the move toward conducting day-to-day financial transactions serves as a strong indicator that participants would prefer and benefit from electronic delivery of plan information, though inertia is holding them back. 27 The ABA’s most current data lags one year behind that presented in the Pew Research Center’s survey results. However, comparing comparable years for Pew and the ABA finds consistent results. 28 This result is consistent with all age groups (18-34, 35-54, and 55 and older) respondents in the ABA customer survey. 12 .

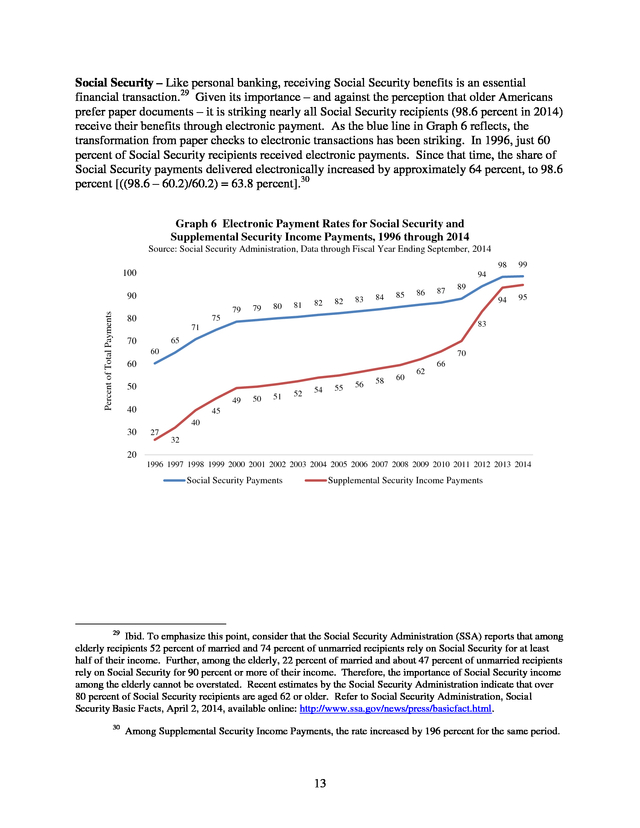

Social Security – Like personal banking, receiving Social Security benefits is an essential financial transaction.29 Given its importance – and against the perception that older Americans prefer paper documents – it is striking nearly all Social Security recipients (98.6 percent in 2014) receive their benefits through electronic payment. As the blue line in Graph 6 reflects, the transformation from paper checks to electronic transactions has been striking. In 1996, just 60 percent of Social Security recipients received electronic payments. Since that time, the share of Social Security payments delivered electronically increased by approximately 64 percent, to 98.6 percent [((98.6 – 60.2)/60.2) = 63.8 percent].30 Graph 6 Electronic Payment Rates for Social Security and Supplemental Security Income Payments, 1996 through 2014 Source: Social Security Administration, Data through Fiscal Year Ending September, 2014 98 95 94 90 Percent of Total Payments 99 94 100 79 79 80 81 82 82 83 84 85 86 87 89 75 80 83 71 65 70 60 70 60 66 50 49 40 50 51 52 54 55 56 58 60 62 45 40 30 27 32 20 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Social Security Payments Supplemental Security Income Payments 29 Ibid.

To emphasize this point, consider that the Social Security Administration (SSA) reports that among elderly recipients 52 percent of married and 74 percent of unmarried recipients rely on Social Security for at least half of their income. Further, among the elderly, 22 percent of married and about 47 percent of unmarried recipients rely on Social Security for 90 percent or more of their income. Therefore, the importance of Social Security income among the elderly cannot be overstated.

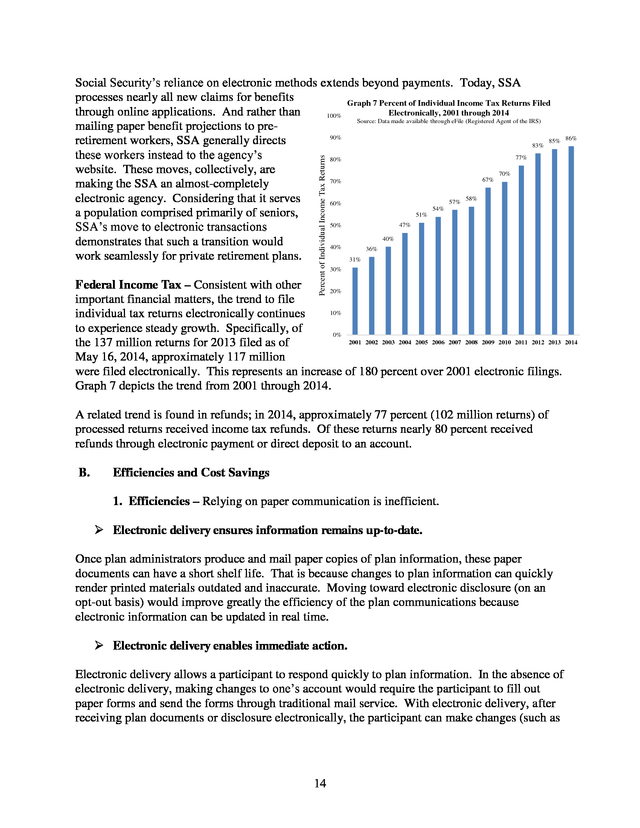

Recent estimates by the Social Security Administration indicate that over 80 percent of Social Security recipients are aged 62 or older. Refer to Social Security Administration, Social Security Basic Facts, April 2, 2014, available online: http://www.ssa.gov/news/press/basicfact.html. 30 Among Supplemental Security Income Payments, the rate increased by 196 percent for the same period. 13 . Percent of Individual Income Tax Returns Social Security’s reliance on electronic methods extends beyond payments. Today, SSA processes nearly all new claims for benefits Graph 7 Percent of Individual Income Tax Returns Filed through online applications. And rather than Electronically, 2001 through 2014 100% Source: Data made available through eFile (Registered Agent of the IRS) mailing paper benefit projections to pre90% 85% retirement workers, SSA generally directs 83% these workers instead to the agency’s 77% 80% website. These moves, collectively, are 70% 67% 70% making the SSA an almost-completely 58% electronic agency.

Considering that it serves 57% 60% 54% a population comprised primarily of seniors, 51% 47% 50% SSA’s move to electronic transactions 40% demonstrates that such a transition would 40% 36% work seamlessly for private retirement plans. 31% 86% 30% Federal Income Tax – Consistent with other 20% important financial matters, the trend to file 10% individual tax returns electronically continues to experience steady growth. Specifically, of 0% 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 the 137 million returns for 2013 filed as of May 16, 2014, approximately 117 million were filed electronically. This represents an increase of 180 percent over 2001 electronic filings. Graph 7 depicts the trend from 2001 through 2014. A related trend is found in refunds; in 2014, approximately 77 percent (102 million returns) of processed returns received income tax refunds.

Of these returns nearly 80 percent received refunds through electronic payment or direct deposit to an account. B. Efficiencies and Cost Savings 1. Efficiencies – Relying on paper communication is inefficient.  Electronic delivery ensures information remains up-to-date. Once plan administrators produce and mail paper copies of plan information, these paper documents can have a short shelf life. That is because changes to plan information can quickly render printed materials outdated and inaccurate.

Moving toward electronic disclosure (on an opt-out basis) would improve greatly the efficiency of the plan communications because electronic information can be updated in real time.  Electronic delivery enables immediate action. Electronic delivery allows a participant to respond quickly to plan information. In the absence of electronic delivery, making changes to one’s account would require the participant to fill out paper forms and send the forms through traditional mail service. With electronic delivery, after receiving plan documents or disclosure electronically, the participant can make changes (such as 14 .

increasing deferral rates or diversifying investment options) with just a few ‘clicks of the mouse.’  Electronic delivery provides information that is more accessible – and digestible. Electronic delivery also provides information of superior quality. For instance, when available on a secure website, online material tends to be clearer and better organized, giving participants an ability easily to access the particular document or information they desire. Generally, websites present information on separate tabs that bring up only the relevant materials. This provides a concise format for the user to page through materials in a methodical, digestible fashion. Moreover, because electronic materials are searchable through online tools, participants can use hyperlinks or the find function to more readily locate specific information, without needing to wade through pages and pages of printed materials. Online access ensures that plan information is always available and in a form that is userfriendly.

Meanwhile, paper documents may tend to “collect dust” on a participant’s desk. This is consistent with findings from the Greenwald & Associates survey that found plan participants agreed overwhelmingly (81 percent) that electronic delivery reduces clutter.31 Online storage provides unlimited access to current and past plan information, improving the participant’s ability to analyze relevant information. Further, electronic access to pension disclosures and communications means that this material and content is always available in a central repository, eliminating the need to look around one’s house or office for the ever-elusive paper copy.  Electronic delivery provides information that can be more readily customized. Plan administrators can alter the online experience to cater to participants needs.

They are able to adapt quickly to improve the presentation, based on participant feedback. Alternatively, plans can address specific concerns of the users as characteristics and needs of the participants may change over time. In both cases, once the administrator identifies the participants’ needs, the changes can be made quickly.  Electronic delivery provides a better guarantee of actual receipt of information. Electronic delivery also has the advantage of immediately alerting the sender to delivery issues. In contrast, delivery of paper documents and disclosures remains a significant problem for many plans.

For instance, in 2012, the defined contribution plan for federal employees, the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP), received over 500,000 pieces of return U.S. mail. TSP cites a number of costs associated with this volume of returned mail.

First, they cite the waste in printing and mailing costs. Second, TSP notes that high return-mail volume could jeopardize favorable 31 Refer to Appendix A for the complete results of the Greenwald & Associates survey. 15 . mailing rates (discounted rate) that the U.S. Postal Service provides for mass mailings. Finally, TSP acknowledges that returned mailing of plan documents could increase the chance of fraud and decrease account security.32 32 Refer to the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board, Strategic Plan, 2014, page 19. 16 . 2. Cost Savings – Compared to traditional mailing of plan documents, electronic delivery has significantly lower costs. A recent study estimates that moving from paper to electronic delivery of certain documents could reduce costs of producing communications by 36 percent.33 By way of illustration, the TSP attributes the use of electronic delivery of plan documents and electronic communication as an important factor that contributes to its lower administrative costs.34 In 2003, the TSP changed its policy from default delivery of participants’ quarterly benefit statements by mail to electronic, paperless delivery. TSP estimates that this change reduced the costs by $7 to $8 million dollars in 2006 (the first year it was phased-in fully),35 savings that presumably were passed back to participants through lower fees. Similarly, SSA realized an estimated $120 million annual cost savings when the agency shifted to electronic benefit delivery.

A recent report indicated that by phasing out paper Social Security checks entirely is expected to save taxpayers more than $1 billion over 10 years.36 TSP and SSA’s move toward electronic communication is consistent with the Executive Orders issued by the President and the subsequent memorandum issued by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), to encourage specifically the use of electronic communication across government agencies and “smart disclosures.” OMB encourages electronic communication stating that it can reduce burdens and increase efficiency. Specifically, the OMB states: Smart disclosure makes information not merely available, but also accessible and usable by structuring disclosed data in standardized, machine readable formats … In many cases, smart disclosure enables third parties to analyze, repackage, and reuse information to build tools that help individual consumers to make more informed choices in the marketplace.37 33 Refer to Martin Murray, Electronic Data Interchanges, Supply Chain Logistics, available online: http://logistics.about.com/od/supplychainsoftware/a/Electronic-Data-Interchange-Edi.htm. 34 While there are many structural differences that account for the TSP’s lower administrative costs, allowing electronic delivery of documents is an important contributing factor to this cost savings. 35 Refer to the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board, Minutes of the Meeting of the Board Members, February 20, 2007. Note to address concerns with fraud and notification requirements, they continued to send annual statements in the mail. 36 Refer to the U.S.

Government Accountability Office, Electronic Transfers, Many Programs Electronically Disburse Federal Benefits, and More Outreach Could Increase Use, GAO-08-645, June 2008 and comments by Treasurer Rosie Rios, available online: http://usgovinfo.about.com/od/federalbenefitprograms/a/NoMore-Paper-Social-Security-Checks.htm. 37 Refer to the Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President, Reducing Reporting and Paperwork Burdens, Memo dated June 22, 2012 and Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President, Informing Consumers through Smart Disclosure, Memo dated September 8, 2011. 17 . 3. Electronic Delivery Benefits Participants – Allowing pension plan administrators to use electronic delivery (with an opt-out feature) would reduce the costs associated with their plans. Plan administrators would experience reduced printing, mailing, and storage costs. These cost savings would reduce their overall administrative costs and will ultimately benefit participants.38 Reducing administrative costs translates to lower expenses – and higher net investment returns – to the participant.39 Estimates to quantify the savings from moving to electronic disclosure requires first estimating per-participant cost savings, which would apply only to participants that currently receive traditional mailing and would convert to electronic delivery if that default were available to plans.

Therefore, the analysis must characterize the current delivery status of participants and assumptions regarding the behavioral response of these plan participants (regarding the potential to opt-out). To characterize the current delivery status, we rely on the results of a Greenwald & Associates telephone survey, explained in Section III of this white paper.40 This survey found that 14 percent of plan participants currently receive plan communication in electronic form. In addition, the Greenwald survey identified the remaining participants according to those that currently receive documents in both formats (37 percent) and those receiving only paper (49 percent). Based on the documents displayed in Table 1, the analysis assumes that each participant receives an estimated 8 to 12 plan documents that could be delivered electronically.

The cost associated with preparing the documents includes certain fixed costs associated with producing the documents and the variable costs associated with printing and sending the documents. The plan administrator would still incur the fixed costs. But variable costs – attributable to reduced paper costs, printing services, labor associated with mailing the documents, and postage – would be eliminated through electronic delivery. To estimate comparable costs for allowing plan administrators to move to electronic delivery (with an opt-out provision), our analysis relies on a study produced by the mutual fund industry in connection with the Securities and Exchange Commission’s summary prospectus rule.41 This study provided per document printing costs for various printing quality (color versus black and white documents).

The analysis relied on U.S. Postal Service rates for first class mailing and bulk mailing rates for the postage fees. 38 Refer to Appendix B for a description of the estimated cost savings and the assumptions supporting the benefits to plan participants. 39 The provision would not affect the gross investment rate of return that a given investment instrument would earn. However, the participant receives the investment return net of fees and administrative costs.

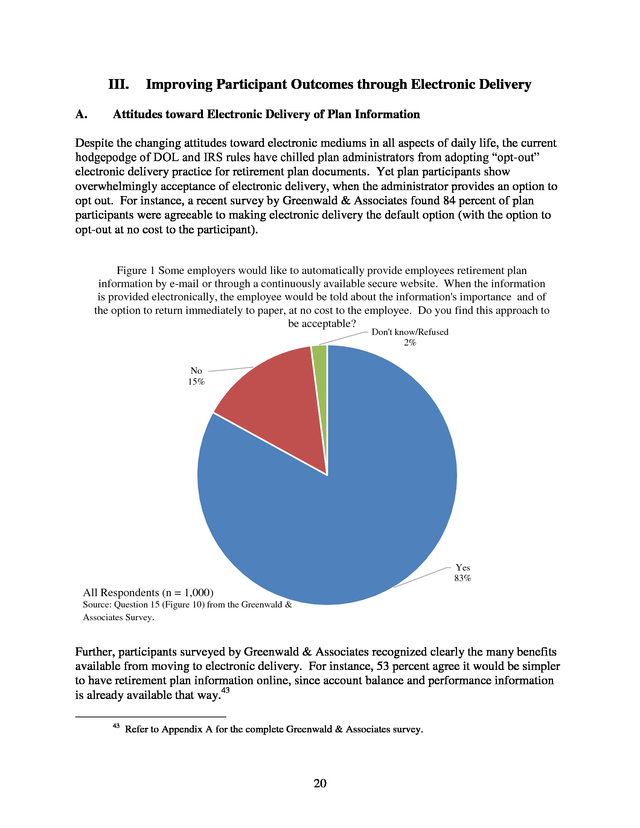

Reducing these costs would result in a higher net investment return. 40 Refer to Appendix A for the complete Greenwald & Associates survey. 41 Refer to Investment Company Institute, Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Summary Prospectus Proposal, February 28, 2008, Appendix B. 18 . Applying these costs to retirement plan participants (total 130 million participants adjusted for likely behavioral responses and eliminating those that receive electronically certain documents) and the number of communications required by law (estimated 8 to 12 documents per participant), our analysis outlined in Appendix B finds that total annual savings associated with moving to electronic delivery would range between $300 and $750 million each year, of which an estimated $200 to $500 million in savings would accrue directly to plan participants annually.42 42 Given the degree of competition for plan administration services, nearly 70 percent is likely to pass through to the participant in the form of lower fees (higher net investment return). 19 . III. A. Improving Participant Outcomes through Electronic Delivery Attitudes toward Electronic Delivery of Plan Information Despite the changing attitudes toward electronic mediums in all aspects of daily life, the current hodgepodge of DOL and IRS rules have chilled plan administrators from adopting “opt-out” electronic delivery practice for retirement plan documents. Yet plan participants show overwhelmingly acceptance of electronic delivery, when the administrator provides an option to opt out. For instance, a recent survey by Greenwald & Associates found 84 percent of plan participants were agreeable to making electronic delivery the default option (with the option to opt-out at no cost to the participant). Figure 1 Some employers would like to automatically provide employees retirement plan information by e-mail or through a continuously available secure website. When the information is provided electronically, the employee would be told about the information's importance and of the option to return immediately to paper, at no cost to the employee.

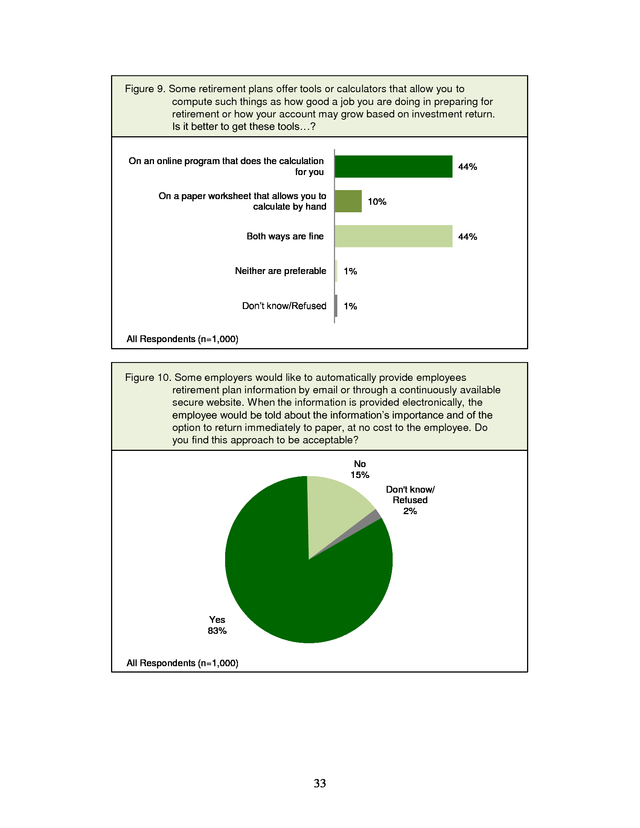

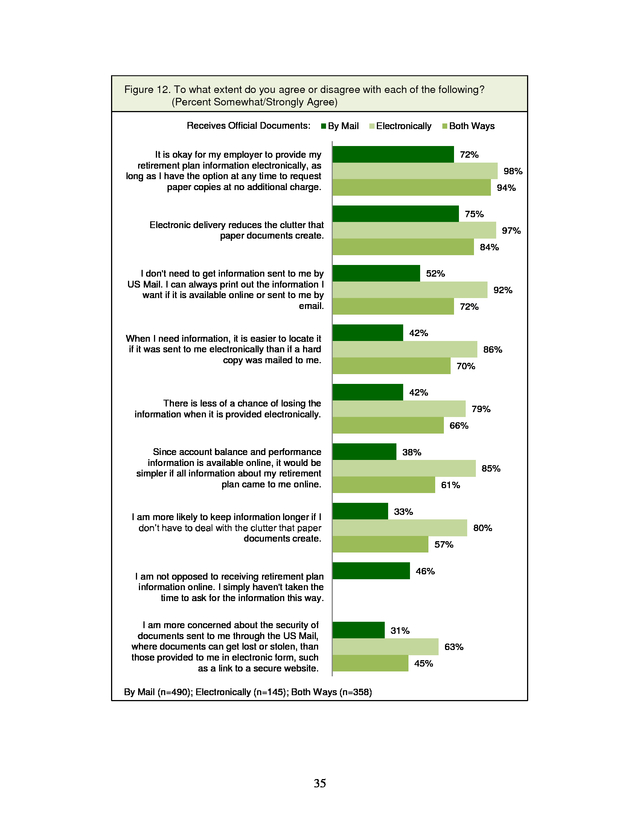

Do you find this approach to be acceptable? Don't know/Refused 2% No 15% Yes 83% All Respondents (n = 1,000) Source: Question 15 (Figure 10) from the Greenwald & Associates Survey. Further, participants surveyed by Greenwald & Associates recognized clearly the many benefits available from moving to electronic delivery. For instance, 53 percent agree it would be simpler to have retirement plan information online, since account balance and performance information is already available that way.43 43 Refer to Appendix A for the complete Greenwald & Associates survey. 20 . Respondents to the survey indicated that the potential benefits to plan participants, including convenience, improved security, and cost reductions that will inure to participants’ benefit are reasons to choose electronic delivery. B. Enhancing Retirement Savings through Electronic Delivery When plans notify participants that their plan information is available through secure Internet access, participants enjoy a number of benefits. Directing participants to electronic mediums encourages the use of electronic tools that ultimately play an important role in promoting superior retirement outcomes. For instance, when participants access online plan disclosures, the provider can easily direct the participant to a simple benefit calculator tool. Use of this tool enables participants to run projections of income in retirement. Among participants expressing a preference, online calculators (44 percent) were more than four times as popular as paper worksheets (10 percent).44 Figure 2 displays the participant responses to the survey questions regarding online tools and calculators.

As shown, participants in the Greenwald survey preferred online to paper-only tools and calculators. Figure 2 Some retirement plans offer tools or calculators that allow you to compute such things as how good a job you are doing in preparing for retirement or how your account may grow based on investment return. Is it better to get these tools…? On an online program that does the calculation for you On a paper worksheet that allows you to calculate by hand 44% 10% Both ways are fine 44% Neither is preferable 1% Don't know/Refused 1% All Respondents (n = 1,000) Source: Figure 9 from the Greenwald & Associates Survey. Accordingly, provider data already show that exposure to such a calculator encourages participants to increase deferrals or modify their investment strategy to achieve a secure 44 The remaining participants in the Greenwald survey did not express a preference of one over the other, stating that either would be an acceptable format. 21 . retirement.45 As Graphs 8 and 9 reflect, participants electing electronic delivery have higher average deferral rates relative to that of their counterparts that do not elect electronic delivery. Clearly, across all age classes, the participants electing electronic delivery defer at a rate twice that of their counterparts. While these observations do not suggest that electronic deliver alone will increase deferral rates, it does provide a sense of the participants’ interest and awareness of managing their retirement savings to ensure adequacy. Graph 8 Average Deferral Rates for Plan Participants, by Age and Electronic Delivery Status 30% Source: Analysis of Provider A's Confidential Plan Data, 2014 12% Graph 9 Average Deferral Rates for Plan Participants, by Age and Electronic Delivery Status Source: Analysis of Provider B's Confidential Plan Data, 2014 26% 25% 10% 10% 9% 20% 8% Deferral Rate Deferral Rate 20% 16% 15% 13% 11% 10% 11% 6% 6% 6% 5% 5% 4% 9% 4% 8% 7% 6% 7% 3% 3% 6% 5% 5% 2% 0% 0% < 25 25-34 Elected electronic delivery 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+ 20-29 30-39 Elected electronic delivery Did not elect electronic delivery 40-49 50-59 Did not elect electronic delivery In addition, these retirement plan providers found that participants electing electronic delivery also had a greater investment diversity.46 Collectively, these higher deferral rates and investment diversity has led to higher account balances for participants that receive plan communications electronically. Graph 10 displays the contrast in account balance, by participant age, for those that elect electronic delivery and those that do not for this plan administrator. Across all age groups, the average account balance is 2.76 times greater for those electing electronic delivery compared to those participants that do not. 45 Analysis of the plan administrator’s data indicate that participants electing electronic delivery tend to distribute their savings across a greater number of investment funds compared to those that do not elect electronic delivery (6.29 compared to 5.58 across all age groups). 46 Participants that elected electronic delivery tended to have their retirement savings a greater number of investment vehicles.

Diversity in investments tends to spread and reduce risk, thus contributing to higher future account balances. 22 60-69 . $400,000 Average Account Balance $350,000 Graph 10 Average Account Balances, by Electronic Delivery Status, by Participant Age $342,214 Source: Analysis of Provider A's Confidential Plan Data, 2014 $300,000 $269,305 $250,000 $193,972 $200,000 $150,000 $110,930 $105,706 $91,297 $100,000 $67,963 $50,000 $6,210 $3,209 $37,578 $14,926 $38,713 $0 younger than 25 years 25-34 years 35-44 years 45-54 years 55-64 years 65 or more years Participant Age Did Not Elect E-Delivery Elected E-Delivery Many retirement plan providers adapt online calculators to integrate information about other benefits (e.g., private savings, Social Security, or defined benefit plans). Integrating information about other savings provides a complete picture of the participants saving behavior as well as an indicator of whether this behavior will result in adequate retirement savings.47 C. Automatic Features with Opt-Out Improve Outcomes Proposals to facilitate electronic delivery to pension participants would rely on an important and often-studied provision – the “opt-out” provision of automatic enrollment.48 The power of default rules is widely recognized in the retirement plan context. Consistent with experience in retirement savings, an opt-out provision for electronic delivery will have a significant effect on behavior and ultimately on the outcomes for participants. Indeed, the same principle has been recognized as having cross-cutting utility; as the OMB Administrator recently stated: “[S]ignificant attention has been given to the possibility of improving outcomes by easing and 47 This is consistent with other financial institutions, as most financial information is accessible online and many service providers are developing tools to allow the user or account holder to consolidate financial information for tax purposes. 48 Automatic enrollment began to gain serious momentum for private retirement plans in 2007, following enactment of the Pension Protection Act of 2006.

While automatic enrollment was available in some plans prior to this time, the Act clarified rules regarding employers’ use of automatic enrollment by creating a statutory safe harbor. According to the Profit Sharing Council of America, 49th Annual Survey, only 17.5 percent of plans had offered automatic enrollment in 2005. 23 . simplifying people’s choices. Sometimes this goal can be achieved by…selecting the appropriate starting point or ‘default rules.’” Making opt-out the default rule reflects an understanding of individual behavior, that inertia is a powerful force and often chills individuals from taking actions that they would find beneficial.49 For example, though enrollment in a retirement plan would benefit nearly every eligible worker, many individuals do not enroll when given the opportunity to enroll at the time of employment. There are a number of reasons that this occurs, but behavioral finance studies indicate that inertia is the primary reason.50 As discussed below, Congress has already recognized the danger of inertia, and the Pension Protection Act of 2006 shifted the default rules to facilitate automatic enrollment and escalation – with key benefits for American savers. 1. Auto Enrollment Increases Participation and Deferral Rates – While workers know rationally that participation in an employer-sponsored plan is in their best interest, inertia means that they tend not to affirmatively elect to participate. In contrast, opt-out participation means that the individual must affirmatively elect not to participate.

A recent Vanguard survey indicates that using an opt-out provision drove retirement plan participation rates from 49 without automatic enrollment to 91 percent with automatic enrollment.51 Similarly, Prudential reports that plans with automatic enrollment have participation rates 45 percent higher than those that do not.52 Economic studies confirm this benefit of increased participation and recognize other benefits as well. Specifically, studies find that, as an incentive to save, automatic enrollment (with an optout ability) has an even greater effect on savings rates than employers’ matching contributions.53 49 Nash, Betty Joyce, Opt In or Opt Out Automatic Enrollment Increases Participation, Region Focus, Winter 2007. 50 Knoll, Melissa A. Z., The Role of Behavioral Economics and Behavioral Decision-Making in Americans’ Retirement Savings Decisions, Social Security Bulletin, Vol.

70, No. 4, 2010. In addition, 46 percent of respondents in the Greenwald survey indicated that they have simply not taken the time to ask for information electronically. 51 Vanguard, January 2015 Survey Results, Available online: https://institutional.vanguard.com/iam/pdf/CRRATEP_AutoEnrollDefault.pdf?cbdForceDomain=false.

These statistics are comparable to results of other plans according to Nash (2007) and Olson (2007). 52 Prudential Retirement, Q1 2013 data. Available online: http://research.prudential.com/documents/rp/Automated_Solutions_Paper-RSWP008.pdf. 53 Chetty, Raj, et al., Subsidies vs. Nudges: Which Policies Increase Savings the Most? NBER Working Paper Number 18565, 2013 and Andrietti, Vincenzo, Auto-enrollment, Matching and Participation in 401(k) Plans, October 1, 2014. 24 .

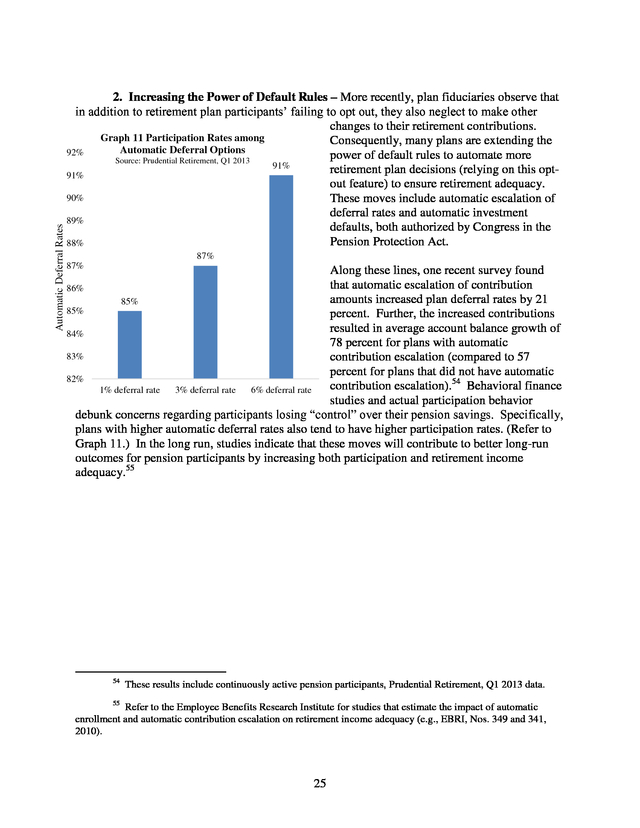

Automatic Deferral Rates 2. Increasing the Power of Default Rules – More recently, plan fiduciaries observe that in addition to retirement plan participants’ failing to opt out, they also neglect to make other changes to their retirement contributions. Graph 11 Participation Rates among Consequently, many plans are extending the Automatic Deferral Options 92% power of default rules to automate more Source: Prudential Retirement, Q1 2013 91% retirement plan decisions (relying on this opt91% out feature) to ensure retirement adequacy. 90% These moves include automatic escalation of deferral rates and automatic investment 89% defaults, both authorized by Congress in the Pension Protection Act. 88% 87% 87% Along these lines, one recent survey found that automatic escalation of contribution 86% amounts increased plan deferral rates by 21 85% 85% percent. Further, the increased contributions resulted in average account balance growth of 84% 78 percent for plans with automatic 83% contribution escalation (compared to 57 percent for plans that did not have automatic 82% contribution escalation).54 Behavioral finance 1% deferral rate 3% deferral rate 6% deferral rate studies and actual participation behavior debunk concerns regarding participants losing “control” over their pension savings. Specifically, plans with higher automatic deferral rates also tend to have higher participation rates.

(Refer to Graph 11.) In the long run, studies indicate that these moves will contribute to better long-run outcomes for pension participants by increasing both participation and retirement income adequacy.55 54 These results include continuously active pension participants, Prudential Retirement, Q1 2013 data. 55 Refer to the Employee Benefits Research Institute for studies that estimate the impact of automatic enrollment and automatic contribution escalation on retirement income adequacy (e.g., EBRI, Nos. 349 and 341, 2010). 25 . IV. CONCLUSION Many plans would like, as a default, to distribute retirement plan information electronically. All participants would be given the right to “opt out” and receive paper communications at no charge. However, current rules stand in the way. The Department of Labor (DOL) and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) have issued extensive rules governing the manner in which plans can distribute retirement plan information electronically. Today’s highly restrictive framework guiding electronic delivery of plan information is antiquated; this framework reflects neither recent years’ emerging information trends and technologies nor these trends and technologies’ many benefits for both participants and plan administrators, nor the behavior economics lessons regarding the power of setting appropriate defaults. Plan participants views, reported in a Greenwald & Associates, show overwhelming acceptance for the move to electronic delivery as the default delivery method.

Participants surveyed indicate an awareness of the many potential benefits of electronic delivery. Besides reducing costs (which are significantly passed through to plan participants), electronic delivery of retirement plan information provides an efficient and reliable means of communicating important plan information – which can facilitate superior participant outcomes. Allowing retirement plan administrators to make electronic delivery a default would reduce the costs associated with their plans. These cost savings would reduce their overall administrative costs and will ultimately benefit participants, translating to lower expenses – and higher net investment returns – to the participant. This translates to an estimated $200 to $500 million in savings that would accrue directly to individual retirement plan participants annually. In addition to costs savings that accrue to participants, directing participants to electronic mediums promotes the use of electronic tools (such as retirement readiness calculators) that ultimately play an important role in promoting superior retirement outcomes.

In fact, mere exposure to online tools has been shown to encourage participants to increase deferrals or modify their investment strategy to achieve a secure retirement. Consequently, participants that receive plan communications electronically have better retirement outcomes. Further, the use of “automatic” rules that facilitate “automatic” behavior has had a critical impact on driving superior outcomes. Recent surveys indicates that using an opt-out provision increased retirement plan participation rates, from 49 without automatic enrollment to 91 percent with automatic enrollment.

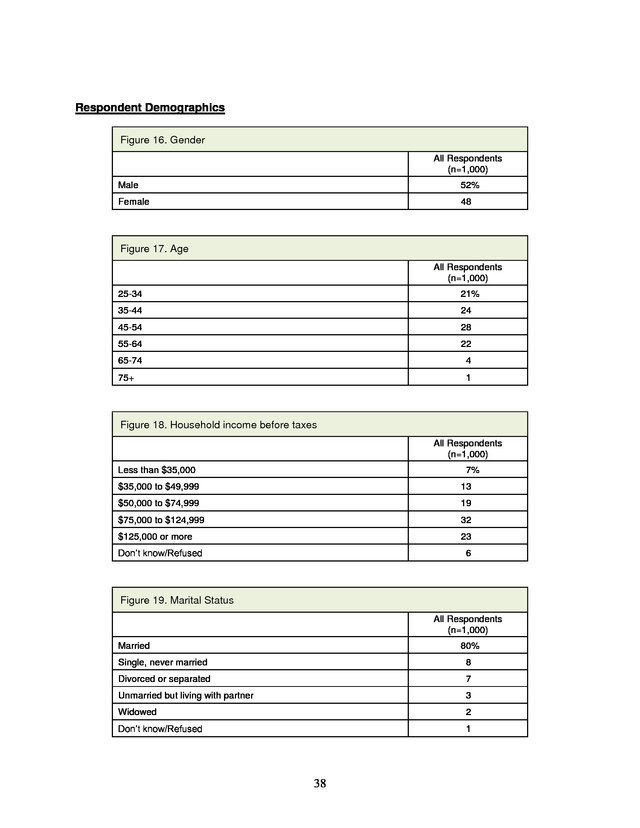

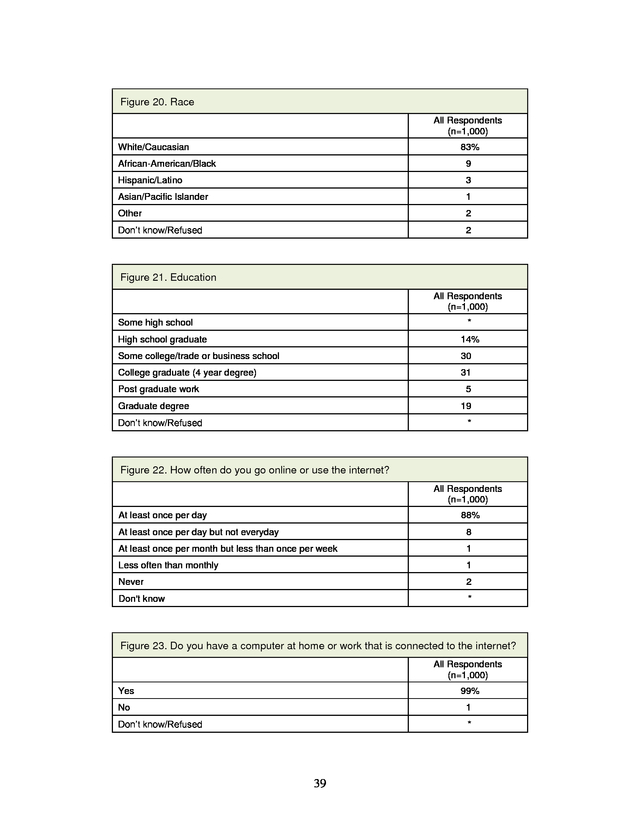

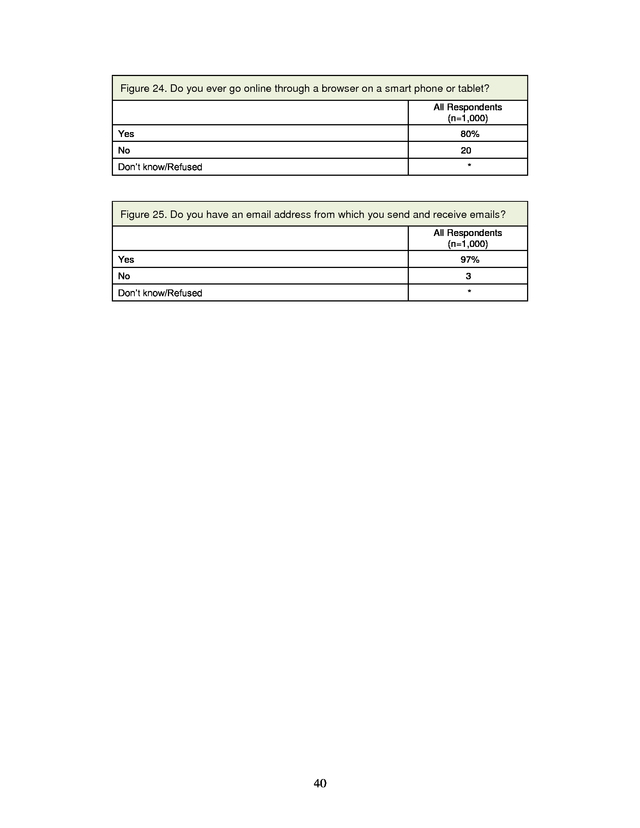

Another recent plan survey found that automatic escalation of contribution amounts increased plan deferral rates by 21 percent and the increased contributions resulted in average account balance growth of 78 percent for plans with automatic contribution escalation. Allowing participants to receive retirement plan information electronically (with the option to opt out at no additional cost) would extend these cost savings to participants and create superior retirement saving outcomes. 26 . APPENDIX A – PLAN PARTICIPANT VIEWS ON PAPER VERSUS ELECTRONIC DELIVERY OF PLAN DOCUMENTS Results of a Telephone Survey, January 2015 Conducted by Greenwald & Associates for the SPARK Institute Purpose This study, commissioned by the SPARK Institute, examines plan participant views toward receiving plan documents and account updates by paper and online. A study conducted by AARP in 2012 found that when given a choice, plan participants, on balance, opted to receive information about their retirement plan by paper rather than online. The purpose of this research is to examine this preference again and to determine if electronic receipt of documents is an acceptable alternative to paper. Methodology A total of 1,000 randomly-selected plan participants nationwide were administered a 10-minute telephone survey. Data collection was done by Greenwald & Associates and its affiliate National Research.

To qualify for the survey, respondents needed to be employed either full or part time and participate in an employer retirement plan. Sample was weighted by age and gender to reflect the demographics of plan participants in the United States, as reported in the Current Population Survey. The study was conducted from December 3th, 2014 to January 2th, 2015 by National Research in Washington, DC. Findings Findings from a study sponsored by the SPARK Institute suggest that a large majority (83%) find it acceptable to receive the information online instead if they have the option to return to paper at no cost (Fig. 10).

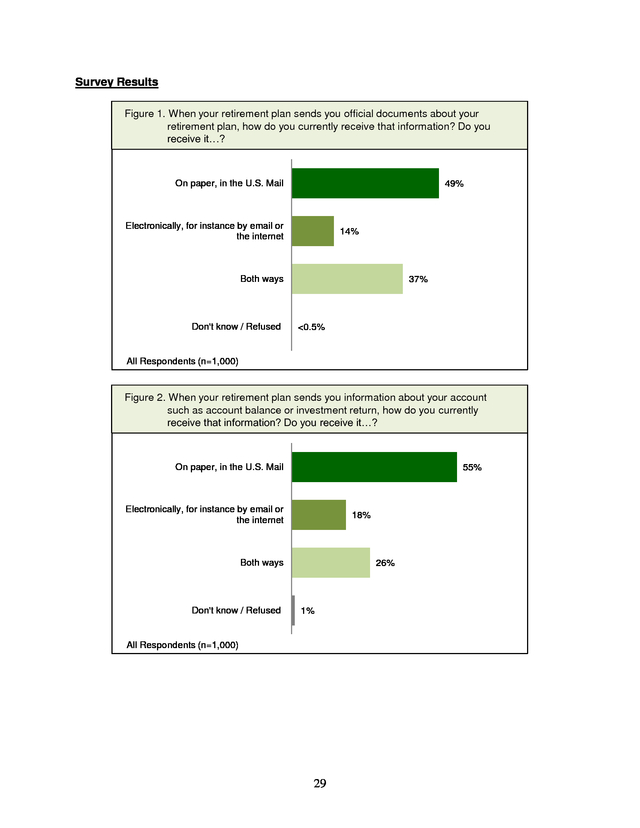

This occurs despite the fact that paper receipt is far more prevalent today. In fact, a significant majority agree with positions that suggest a willingness to consider online receipt. Those under age 50 are even more apt to consider it. Most participants get their official statements by mail today – 49% get it this way only compared to only 14% who receive statements only online (Fig.

1). The number getting statements on paper only, however, is down greatly from 2012, where an AARP study found 62% getting paper only.56 One quarter (25%) of those getting information by paper have some interest in receiving it online (Fig. 3).

Over half of participants (55%) report receiving account information by paper only (Fig. 2). Also of note, virtually all respondents go online either daily (88%) or once per week (8%), suggesting wide access to the internet (Fig. 22). 56 The AARP study also included retired plan participants. 27 .

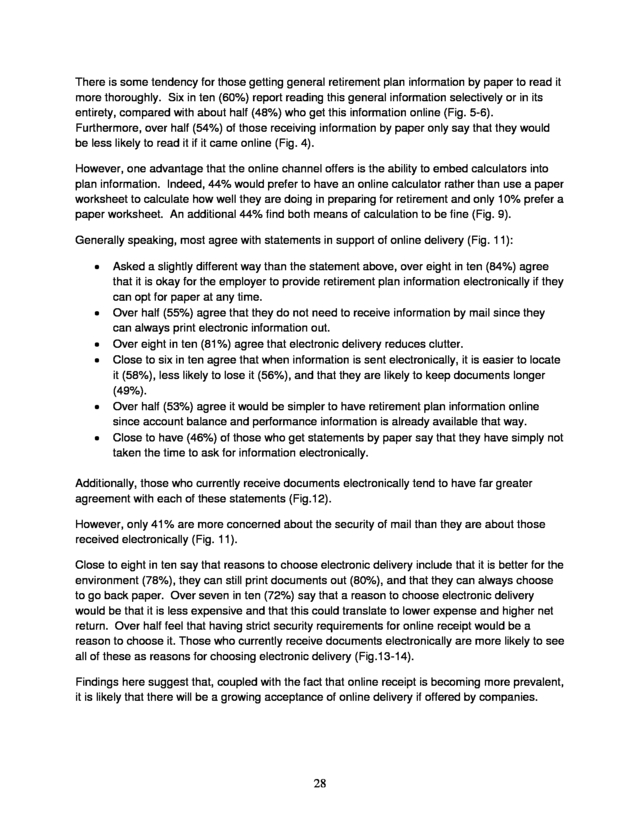

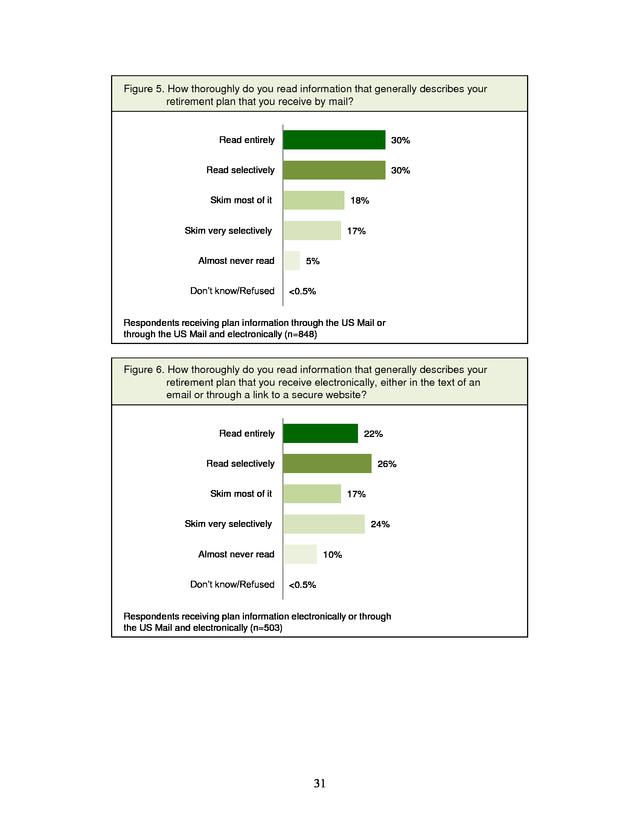

There is some tendency for those getting general retirement plan information by paper to read it more thoroughly. Six in ten (60%) report reading this general information selectively or in its entirety, compared with about half (48%) who get this information online (Fig. 5-6). Furthermore, over half (54%) of those receiving information by paper only say that they would be less likely to read it if it came online (Fig. 4). However, one advantage that the online channel offers is the ability to embed calculators into plan information.

Indeed, 44% would prefer to have an online calculator rather than use a paper worksheet to calculate how well they are doing in preparing for retirement and only 10% prefer a paper worksheet. An additional 44% find both means of calculation to be fine (Fig. 9). Generally speaking, most agree with statements in support of online delivery (Fig.

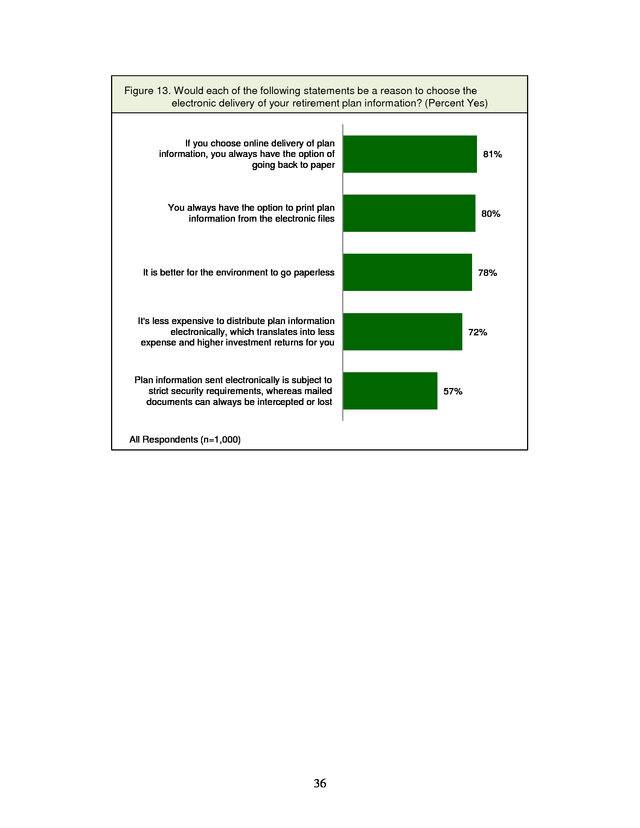

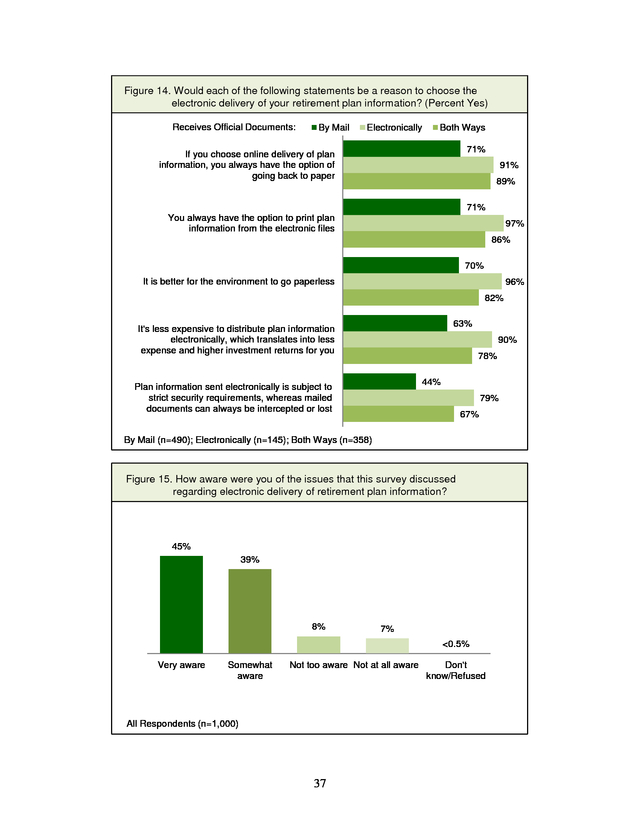

11): ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· Asked a slightly different way than the statement above, over eight in ten (84%) agree that it is okay for the employer to provide retirement plan information electronically if they can opt for paper at any time. Over half (55%) agree that they do not need to receive information by mail since they can always print electronic information out. Over eight in ten (81%) agree that electronic delivery reduces clutter. Close to six in ten agree that when information is sent electronically, it is easier to locate it (58%), less likely to lose it (56%), and that they are likely to keep documents longer (49%). Over half (53%) agree it would be simpler to have retirement plan information online since account balance and performance information is already available that way. Close to have (46%) of those who get statements by paper say that they have simply not taken the time to ask for information electronically. Additionally, those who currently receive documents electronically tend to have far greater agreement with each of these statements (Fig.12). However, only 41% are more concerned about the security of mail than they are about those received electronically (Fig. 11). Close to eight in ten say that reasons to choose electronic delivery include that it is better for the environment (78%), they can still print documents out (80%), and that they can always choose to go back paper. Over seven in ten (72%) say that a reason to choose electronic delivery would be that it is less expensive and that this could translate to lower expense and higher net return.

Over half feel that having strict security requirements for online receipt would be a reason to choose it. Those who currently receive documents electronically are more likely to see all of these as reasons for choosing electronic delivery (Fig.13-14). Findings here suggest that, coupled with the fact that online receipt is becoming more prevalent, it is likely that there will be a growing acceptance of online delivery if offered by companies. 28 . Survey Results Figure 1. When your retirement plan sends you official documents about your retirement plan, how do you currently receive that information? Do you receive it…? On paper, in the U.S. Mail 49% Electronically, for instance by email or the internet 14% Both ways Don't know / Refused 37% <0.5% All Respondents (n=1,000) Figure 2. When your retirement plan sends you information about your account such as account balance or investment return, how do you currently receive that information? Do you receive it…? On paper, in the U.S.