The rise of private placements as an alternative source of funding: a time for innovation and growth - Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law - February 2015

Reed Smith

Description

February 2015

Vol. 30 – No. 2

International

Banking and

Financial Law

Butterworths Journal of

Implications of the failure of the

Bank of England RTGS system

The slender thread of modiï¬ed

universalism after Singularis

Termination provisions of swap

agreements II

In Practice

Developments in freezing foreign assets

Draft EU Regulation on Securities Financing

Transactions

The 2014 French Insolvency Law reform: a

missed opportunity

Cases Analysis

One Essex Court reports on the latest banking

law cases

Market Movements

DLA Piper UK LLP reviews key market

developments in the banking sector

. Contributors to this issue

Professor Dr Kern Alexander is chair for Law and Finance at the University of Zurich. Email: kern.alexander@rwi.uzh.ch

Roger Jones is chairman of the TARGET Working Group. Email: jonesrsj@btinternet.com

Raymond Cox QC is a barrister practising from Fountain Court Chambers, London. Email: rc@fountaincourt.co.uk

Barry Isaacs QC is a barrister practising at South Square in insolvency and restructuring law.

Email: barryisaacs@southsquare.com Andrew Shaw is a barrister practising at South Square in insolvency and restructuring law. Email: andrewshaw@southsquare.com Paul Downes QC heads the 2 Temple Gardens banking & ï¬nance group. Email: pdownes@2tg.co.uk Emily Saunderson is a barrister practising from 2 Temple Gardens, Temple, London.

Email: esaunderson@2tg.co.uk Dr Stephen Connelly is a solicitor and assistant professor at the School of Law, University of Warwick. Email: s j.connelly@warwick.ac.uk Schuyler K Henderson is a consultant, lecturer and author. Email: sk.henderson@btinternet.com Sanjay Patel is a barrister practising from 4 Pump Court, London.

Email: spatel@4pumpcourt.com Nick May is a senior associate in the Herbert Smith Freehills Finance Division. Email: nick.may@hsf.com Rian Matthews is a senior associate in the Commercial Litigation and International Arbitration Group at White & Case LLP. Email: rmatthews@whitecase.com Anthony Pavlovich is a barrister at 3 Verulam Buildings specialising in banking and ï¬nancial law.

Email: apavlovich@3vb.com Hdeel Abdelhady is a Washington DC-based lawyer and the Principal of MassPoint Legal and Strategy Advisory PLLC. Email: habdelhady@law.gwu.edu Ranajoy Basu is a partner in the Structured Finance team at Reed Smith in London. Email: RBasu@ReedSmith.com Monica Dupont-Barton is counsel in the banking practice at Reed Smith in London.

Email: MDupont-Barton@ReedSmith.com Guy O’Keefe is a partner in the ï¬nancing team at Slaughter and May. Email: guy.o’keefe@slaughterandmay.com Edward Fife is a partner in the ï¬nancing team at Slaughter and May. Email: edward.ï¬fe@slaughterandmay.com Harry Bacon is an associate in the ï¬nancing team at Slaughter and May.

Email: harry.bacon@slaughterandmay.com Stephen Moverley Smith QC practises from XXIV Old Buildings, Lincoln’s Inn, London. Email: Stephen.moverley.smith@xxiv.co.uk Heather Murphy practises from XXIV Old Buildings, Lincoln’s Inn, London. Email: heather.murphy@xxiv.co.uk Rachpal Thind is a partner in Sidley Austin’s EU Financial Services Regulatory Group in London.

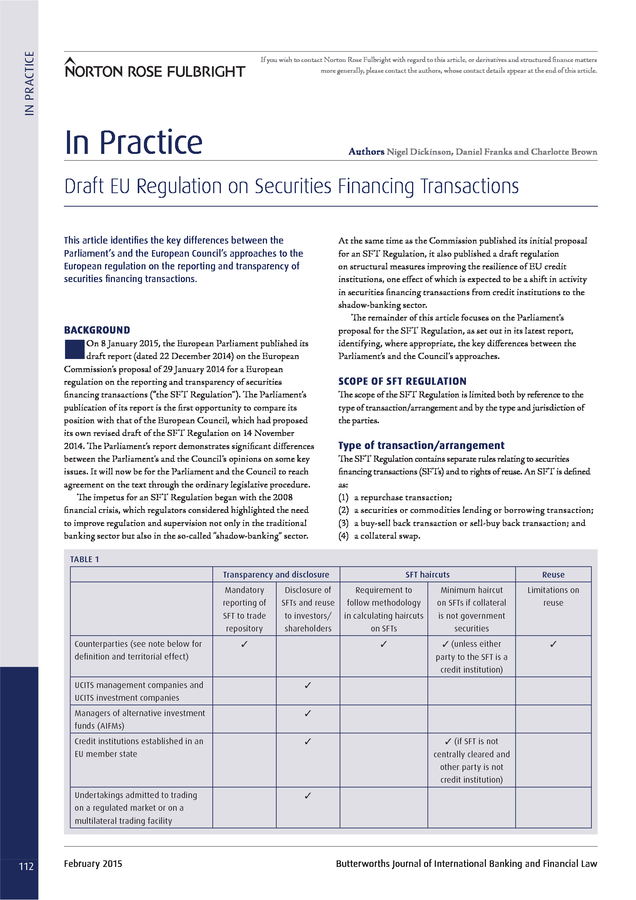

Email: rthind@sidley.com Alice Bell is an associate in Sidley Austin’s EU Financial Services Regulatory Group in London. Email: alice.bell@sidley.com . CONTENTS Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law Vol. 30 No. 2 The rise of private placements as an alternative source of funding: a time for innovation and growth 103 Spotlight Are environmental risks missing in Basel III? February 2015 67 Kern Alexander: The need to address the macro-prudential risks. Ranajoy Basu; Monica Dupont-Barton: Key considerations when structuring private placement transactions in Europe. Punch Taverns’ successful restructuring of £2.2bn of whole-business securitisation debt Features 107 Guy O’Keefe; Edward Fife; Harry Bacon: Considered the most complex corporate restructuring since the rescue of Eurotunnel. Implications of the failure of the Bank of England RTGS system 69 Roger Jones; Raymond Cox QC: It is difficult to see on what basis In Practice the BoE might be liable. Developments in freezing foreign assets The slender thread of modiï¬ed universalism after Singularis Jeremy Andrews; Charles Allin: The decision of the English High Court in ICICI Bank v Diminico. 74 Barry Isaacs QC; Andrew Shaw: The principle of modiï¬ed universalism still lacks clarity in its application. Foreign exchange manipulation: a deluge of claims? Draft EU Regulation on Securities Financing Transactions 112 77 Paul Downes QC; Emily Saunderson: It may well be even harder to get a FOREX-related claim off the ground than a LIBOR claim. Difference and repetition: UK’s “protection” of close out netting from EU rules leaves counterparties worse off 80 Dr Stephen Connelly: Derivative contracts could be exposed to nonnetted bail-in. Termination provisions of swap agreements II 83 Schuyler K Henderson: The Live v Historical debate revisited. “Won’t you stay another day?” The ISDA Resolution Stay Protocol 88 Sanjay Patel: The drafters of the Protocol did not have an easy task. An (un)clear view? Issues to consider in cleared derivative agreements 90 Nick May: Explanation and guidance for buy-side ï¬rms particularly on inclusion of asymmetric terms. Make-whole provisions under New York and English law 93 Rian Matthews: English courts are likely to focus on express words of the parties’ agreement. Banking group companies: which entities are caught by the Special Resolution Regime? 97 Anthony Pavlovich: The exclusions provided by the Order require careful scrutiny. Deposit insurance frameworks for Islamic banks: design and policy considerations 111 Nigel Dickinson; Daniel Franks; Charlotte Brown: Key differences between the Parliament’s and Council’s approaches. 2014 French Insolvency Law reform: missed opportunity? 115 Bruno Basuyaux; Emilie Haroche: Improvement of creditors’ rights. Regulars 116 118 120 124 126 127 Financial Crime Update by Paul Bogan QC Case Analysis by One Essex Court Regulation Update by Norton Rose Fulbright Market Movements by DLA Piper UK LLP Deals Legalease with Lexis®PSL Banking and Finance Online Features THIS SECTION IS ONLY AVAILABLE ONLINE IN LEXIS LIBRARY TO SUBSCRIBERS OF THE LEXIS LIBRARY SERVICE JIBFL-only subscribers will be able to access these features one month after publication at http://blogs.lexisnexis.co.uk/loanranger/ Sovereign bond collective action clauses: issues arising [2015] 2 JIBFL 128A Stephen Moverley Smith QC; Heather Murphy: The motivation behind attempts to regulate in this area. UK supervision of international banks: issues impacting non-EEA branches [2015] 2 JIBFL 128B 99 Hdeel Abdelhady: How should these be funded and premia assessed? Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law Rachpal Thind; Alice Bell: There remains uncertainty as to the PRA’s process and methodology. February 2015 65 . INFORMATION Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law Consultant Editor John Jarvis QC EDITORIAL BOARD Editor Amanda Cohen aamanda.cohen@gmail.com Ioannis Alexopoulos, DLA Piper, London; Managing Editor Elsa Booth Mr Justice Blair, Royal Courts of Justice, London; Acting Editorial Manager and International Brieï¬ngs Editor Sarah Grainger sarah.grainger@lexisnexis.co.uk Director of Content Simon Collin Editorial Office Lexis House, 30 Farringdon Street, London EC4A 4HH Tel: +44 (0) 20 7400 2500 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7400 2583 The journal can be found online at: www.lexisnexis.com/uk/legal Subscription enquiries (hard copy) LexisNexis Butterworths Customer Services Tel: +44 (0) 845 370 1234 Fax: +44 (0) 2890 344212 email: customer.services@lexisnexis.co.uk Electronic product enquiries Butterworths Online Support Team Tel: 0845 608 1188 (UK only) or +44 1483 257726 (international) email: electronic.helpdesk@lexisnexis.co.uk Annual subscription £970 hard copy Printed in the UK by Headley Brothers Ltd, Invicta Press, Queens Road, Ashford, Kent, TN24 8HH This product comes from sustainable forest sources Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law (ISSN 0269-2694) is published by LexisNexis, Lexis House, 30 Farringdon Street, London EC4A 4HH – Tel: +44 (0) 20 7400 2500. Copyright Reed Elsevier (UK) Ltd 2015 (or individual contributors). All rights reserved.No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licencing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1P 0LP. Applications for the copyright owner’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher.

The views expressed in this journal do not necessarily represent the views of LexisNexis, the Editorial Board, the correspondent law ï¬rms or the contributors. No responsibility can be accepted by the publisher for action taken as a result of information contained in this publication. Jeffery Barratt, Norton Rose Fulbright, London; Mr Justice Cranston, Royal Courts of Justice, London; Geoffrey G Gauci, Bristows, London; Sanjev Warna-Kula-Suriya, Slaughter and May, London; Hubert Picarda QC, 9 Old Square (top floor), Lincoln’s Inn, London; Stephen Revell, Freshï¬elds Bruckhaus Deringer, London; Brian W Semkow, School of Business and Management, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology; Philip Wood QC (Hon), Allen & Overy, London; Schuyler K Henderson, consultant, lecturer and author; William Johnston, Arthur Cox, Dublin; Professor Colin Ong, Dr Colin Ong Legal Services, Brunei; Richard Obank, DLA Piper, Leeds; Michael J Bellucci, Milbank, New York; James Palmer, Herbert Smith Freehills, London; Robin Parsons, Sidley Austin LLP, London; visiting lecturer at King’s College, London; Geoffrey Yeowart, Hogan Lovells, London; Gareth Eagles, White & Case, London; Susan Wong, WongPartnership LLP, Singapore; Jonathan Lawrence, K&L Gates, London; Kit Jarvis, Fieldï¬sher, London. PSL ADVISORY PANEL Rachael MacKay, Herbert Smith Freehills, London; Jaya Gupta, Allen & Overy, London; Julia Machin, Clifford Chance, London; Paul Sidle, Linklaters, London; Michael Green, Allen & Overy, London; Anne MacPherson, Kirkland & Ellis LLP, London. CORRESPONDENT LAW FIRMS ASEAN CORRESPONDENT: Dr Colin Ong Legal Services ARGENTINA: onetto, Abogados IRELAND: Arthur Cox DENMARK: Gorrissen Federspiel SCOTLAND: Brodies FINLAND: Roschier SINGAPORE: WongPartnership LLP SOUTH AFRICA: Bowman Gilï¬llan AUSTRIA: Wolf Theiss GERMANY: Noerr JAPAN: Clifford Chance SPAIN: Uria Menendez BELGIUM: Allen & Overy HONG KONG: Johnson, Stokes & Master SWEDEN: Cederquist CENTRAL & EASTERN EUROPE: Noerr INDIA: Global Law Review CHINA: Allen & Overy US: White & Case; Millbank RUSSIA: Clifford Chance February 2015 FRANCE: Jeantet Associés ITALY: Allen & Overy NETHERLANDS: Nauta Dutilh 66 AUSTRALIA: Allens MALTA: Ganado & Associates Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law . Spotlight SPOTLIGHT KEY POINTS Basel III already requires banks to assess the impact of speciï¬c environmental risks on a bank’s credit and operational risk exposures. A recent report suggests Basel III is not being used to its full capacity to address systemic environmental risks. China, Brazil and Peru have engaged in a variety of innovative regulatory and market practices to control environmental systemic risks. Author Kern Alexander Are environmental risks missing in Basel III? This article questions whether Basel III should address the macro-prudential or portfolio-wide environmental risks for banks. â– The role of the ï¬nancial system in the economy and broader society is to provide the necessary ï¬nancing and liquidity for human and economic activity to thrive; not only today but also tomorrow. In other words, its role is to fund a stable and sustainable economy. The role of ï¬nancial regulators is to ensure that excessive risks that would threaten the stability of the ï¬nancial system – and hence imperil the stability and sustainability of the economy – are not taken. In the wake of the ï¬nancial crisis of 2007-08, the G20 initiated at the Pittsburgh Heads of State Summit in September 2009 an extensive reform of banking regulation with the overall aim “to generate strong, sustainable and balanced global growth”. At the same time, the Earth’s planetary boundaries – deï¬ned as thresholds that, if crossed, could generate unacceptable environmental changes for humanity, such as climate change – are under increasing stress and represent a source of increasing cost to the global economy and a potential threat to ï¬nancial stability. Indeed, World Bank President Jim Yong Kim stated at the World Economic Forum in 2014 that “ï¬nancial regulators must take the lead in addressing climate change risks”. ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS An important question arises as to whether international banking regulation (ie Basel III) adequately addresses systemic environmental risks.

For example, the macro-prudential economic risks associated with the banking sector’s exposure to high carbon assets. Basel III has already taken important steps to address both micro-prudential and macro-prudential systemic risks in the banking sector by increasing capital and liquidity requirements and requiring regulators to challenge banks more in the construction of their risk models and for banks to undergo more frequent and demanding stress tests. Moreover, under Pillar 2, banks must undergo a supervisory review of their corporate governance and risk management practices that aims, among other things, to diversify risk exposures across asset classes and to detect macro-prudential risks across the ï¬nancial sector.

Regarding environmental risks, Basel III already requires banks to INNOVATIVE PRACTICES A recent report supported by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the University of Cambridge suggests that Basel III is not being used to its full capacity to address systemic environmental risks and that such risks are in the “collective blind spot of bank supervisors”. Despite the fact that history demonstrates direct and indirect links between systemic environmental risks and banking sector stability – and that evidence suggests this trend will continue to become more pronounced and complex as environmental sustainability risks grow for the global economy – Basel III has yet to take explicit account of, and therefore only marginally addresses, the environmental risks that could threaten banking sector stability. Despite no action by the Basel Committee to address systemic environmental risks at “...

Basel III already requires banks to assess the impact of speciï¬c environmental risks on the bank’s credit and operational risks exposures, but these are mainly transaction-speciï¬c risks...” assess the impact of speciï¬c environmental risks on the bank’s credit and operational risks exposures, but these are mainly transaction-speciï¬c risks that affect the borrower’s ability to repay a loan or address the “deep pockets” doctrine of lender liability for damages and the cost of property clean-up. These transaction speciï¬c risks are narrowly deï¬ned and do not constitute broader macro-prudential or portfolio-wide risks for the bank that could arise from its exposure to systemic environmental risks. Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law the international level, some countries – China, Brazil and Peru under the aegis of the International Finance Corporation’s Sustainability Banking Network (SBN) – have already engaged in a variety of innovative regulatory and market practices to control environmental systemic risks and adopt practices to mitigate the banking sector’s exposure to environmentally unsustainable activity. These initiatives have been based on existing regulatory mandates to promote ï¬nancial stability by acting through the February 2015 67 . SPOTLIGHT Spotlight existing Basel III framework to identify and manage banking risks both at the transaction speciï¬c level and at the broader portfolio level. What is signiï¬cant about these various country and market practices is that the regulatory approaches used to enhance the bank’s risk assessment fall into two areas: 1) Greater interaction between the regulator and the bank in assessing wider portfolio level ï¬nancial, social and political risks; and 2) banks’ enhanced disclosure to the market regarding their exposures to systemic environmental risks. These innovative Biog box Professor Dr Kern Alexander is chair for Law and Finance at the University of Zurich. Email: kern.alexander@rwi.uzh.ch regulatory approaches and market practices are the result of pro-active policymakers and regulators adjusting to a changing world. Other international bodies, such as the SBN and UNEP Finance Initiative, have sought to promote further dialogue between practitioners and regulators on environmental sustainability issues and to encourage a better understanding of these issues by ï¬nancial regulators. China, Brazil and Peru, among others, have all embarked on innovative risk assessment programmes to assess systemic environmental risks from a macro- prudential perspective as they recognise the materiality of systemic environmental risks to banking stability.

The Basel Committee should take notice. Further reading Basel III drives changes to capital instruments [2012] 10 JIBFL 636 Rebuilding international ï¬nancial regulation [2011] 8 JIBFL 489 Lexisnexis Financial Services blog: What next for the Basel III leverage ratio framework? Butterworths Company Law Handbook 27th Edition & Tolley’s Company Law Handbook 21st Edition Butterworths and Tolley’s Company Law Handbooks will ensure compliance and best practice — they are comprehensive and include consolidated legislation and the latest developments in company law. Butterworths Company Law Handbook 27th Edition, key highlights: • The key new piece of legislation is the newly enacted Financial Services Act 2012.This Act implements signiï¬cant changes to the UK ï¬nancial regulation framework by making some 2,704 amendments to the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 alone. • Major amendments made to CA2006 by the enterprise and Regulartory Reform Act 2013 concerning directors’ renumeration. • Companies Act 2006 (Amendment of Part 25) Regulations 2013 – which repeal and replace the CA2006 provisions relating to the registration of company charges. Tolley’s Company Law Handbook 21st Edition, key highlights: • Commentary on the change which removes the upper limit for ï¬nes imposed on companies and directors in the Magistrates’ Courts. This will mean there will no longer be the maximum £5000 ï¬ne payable, but ï¬nes will be potentially unlimited. • The chapters on Corporate Governance, Listing Rules and Prospectuses will be updated to reflect changes to the Listing Rules, the Prospectus Rules and the UK Corporate Governance Code. • Coverage of wide ranging accounting and audit regulations which include increasing the amount of small companies being exempt. SAVE over £18* when you order both titles online: www.lexisnexis. co.uk/2013companylaw. Or call 0845 370 1234 quoting reference 16603IN.** *Represents a £13 discount applied when you order both Tolley and Butterworths Company Law Handbooks. Also, all on-line orders are exempt of P&P charges, saving £5.45.

**Telephone orders are subject to a P&P charge of £5.45. 68 February 2015 Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law . Feature Authors Roger Jones and Raymond Cox QC Implications of the failure of the Bank of England RTGS system This article considers what happens if the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) System operated by the Bank of England (BoE) fails – ie there is an outage. After setting out the background to RTGS, and the critical role and importance of RTGS at the heart of the UK ï¬nancial infrastructure, the implications of an outage are analysed. This is done in relation to the BoE which operates RTGS, and to CREST and CHAPS which in different ways are more immediately dependent on RTGS than retail payment systems which normally settle in RTGS at less frequent intervals or sometimes at the end of the day. It is difï¬cult to see on what basis the BoE might be liable to an RTGS account holder for an outage.

There is more scope for users of CHAPS to make a claim against a counterparty arising from the delays caused by an outage since uniquely, in normal operation, CHAPS payments require a compensating individual RTGS transfer before being executed; and this possibility should be taken into account in documenting transactions. There is also a brief reference to euro settlement in CREST through the TARGET 2 RTGS system. RTGS OUTAGES Introduction â– On 20 October 2014, the Bank of England’s (BoE) Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) System suffered a lengthy technical outage lasting almost ten hours. Whilst several ï¬nancial market infrastructures (FMIs) including CREST and various retail payment systems settle through RTGS, the one most affected was the CHAPS system under which, unlike the other FMIs, individual payments are settled in RTGS before being executed.

A report by Deloitte on the causes of the outage and effectiveness of the BoE’s response is awaited. Background The problems arising from outages of RTGS systems are relatively recent, because the systems themselves are not old. Probably the best known forerunner of modern RTGS systems was the 1970 version of FEDWIRE in the USA which was based on a computerised, high speed (for the time) electronic telecommunications and processing network. One of the earliest analyses of the essential nature of an RTGS system was undertaken in the so-called Noel Report (Central Bank Payment and Settlement Services with respect to CrossBorder and Multi-Currency Transactions dated September 1993 and published by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS)). This focused on the concept of intra-day ï¬nal transfer which it deï¬ned as the ability to indicate and to receive timely conï¬rmation of transfers between accounts at the central bank of issue that become ï¬nal within a brief period of time. they have become.

Nevertheless, the Noel Report was an important staging post in recognising the importance of payment systems, and particularly RTGS systems, in mitigating risk. The work done by the Noel Committee and subsequent central bank groups undoubtedly played a major part in the resilience of payment systems in the 2007/08 ï¬nancial crisis, without which it could have been much worse. As thinking developed, a March 1997 report by the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems (CPSS) of the G10 central banks in respect of RTGS systems deï¬ned RTGS as effecting ï¬nal settlement of inter-bank funds transfers on a continuous transaction by transaction basis throughout the processing day and this remains at the core of current thinking. This CPSS report was again published by the BIS which gave it added authority.

Whilst the design and structure of RTGS systems differs depending on local needs, the core attributes are similar. In this article we focus on the BoE RTGS system, although many of the same considerations would apply to other systems. IMPLICATIONS OF THE FAILURE OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND RTGS SYSTEM KEY POINTS It is difficult to see on what basis the Bank of England might be liable to an RTGS account holder for an outage. There is more scope for users of CHAPS to make a claim. CREST is remarkably well insulated from problems caused by an RTGS outage. “A 1997 report... deï¬ned RTGS as effecting ï¬nal settlement of inter-bank funds transfers on a continuous transaction by transaction basis throughout the processing day...” Not surprisingly, the phrase “brief period of time” gave rise to considerable discussion, with central banks interpreting it with varying degrees of purity.

Also, the legal environment was less developed than now with concepts such as “zero hour” under which transactions could be unwound back to the previous midnight still being relatively widespread. Furthermore, liquidity optimisation techniques were far less advanced than Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law The signiï¬cance of outages In addition to money transmission, the BoE’s RTGS system is central to: the conduct of monetary policy operations; ancillary systems including not only payment systems but also other FMIs such as securities settlement systems; some other forms of wholesale transactions; and the provision of central bank liquidity. February 2015 69 . IMPLICATIONS OF THE FAILURE OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND RTGS SYSTEM Feature With the increasing importance being attached by regulators to settlement of high value transactions in central bank funds, RTGS systems are critical to an increasing number of wholesale market operations. However, irrespective of the nature of the operation, liquidity is needed for a transfer of money through an RTGS system to be effected, hence the importance of participants having sufficient intraday liquidity when and where needed cannot be overstated. Also in an interconnected world, a delayed transaction in one RTGS system may affect others through, for example, the CLS (Continuous Linked Settlement) foreign exchange settlement system. It follows, therefore, that the RTGS system sits at the heart of the UK ï¬nancial infrastructure, and a major RTGS outage could have systemic implications. serious liquidity imbalances can occur potentially leading to gridlock. In times of ï¬nancial stress, such effects could be magniï¬ed. Contingency plans It is of course important to recognise that disruptive events, whether malicious or accidental, can affect even the best designed and run IT systems.

Best practice requires the operator to be able to resume operations within two hours. This normally requires the duplication of hardware and software on at least two sites which have independent utility connectivity and with the back-up site(s) being able to operate even in the event of the destruction of the primary site, including the non-availability of staff working there. It is regarded as good practice to switch primary operations “... a number of other FMIs...

settle through RTGS but unlike CHAPS they are not dependent on RTGS to process each individual transaction prior to release” Risks Technical and operational failure is not the only issue which can affect RTGS systems. Legal robustness is essential. Reliance on third party utilities is frequently critical and ranges from such basic infrastructure as power and water to more sophisticated threats such as cyber warfare. Other possible issues may range from natural catastrophes and exceptional weather to political instability and industrial action.

Another very important factor is the need to ensure that adequately trained staff and decision-makers are always available since unfortunately disruptive events can occur at the most inconvenient time. Since for many of their operations, RTGS systems depend on the receipt of instructions from their participants, both ï¬nancial institutions and FMIs (and vice versa), it is important that effective contingency plans exist in case the relevant data channels are disrupted, otherwise 70 February 2015 between sites where this is possible. Distance between the sites is obviously important but can make real time copying of data more difficult. In February 2014 the BoE became the ï¬rst central bank to adopt a SWIFT system known as MIRS (Market Infrastructure Resiliency Service). This is a basic contingency infrastructure which is completely independent of the underlying RTGS system and avoids the potential problem whereby a software bug could affect both primary and secondary sites. MIRS relies on information contained in SWIFT messaging which many RTGS systems use for connectivity. SWIFT is the bank-owned co-operative which provides messaging services for ï¬nancial services applications.

However, it is not clear whether MIRS was actually activated in respect of the 20 October outage. Finally, when a problem does occur, the importance of prompt and effective communication to the market, not only banks and other affected ï¬nancial institutions but also ï¬nancial market infrastructures which use the RTGS system for settlement, cannot be overestimated. This is essential in order to enable them to manage their own risks. LEGAL IMPLICATIONS We turn now to consider some of the legal issues which may theoretically arise in relation to an outage of the RTGS operated by the BoE. The BoE’s RTGS system settles CHAPS payments between a paying bank and a payee bank by debiting the former’s settlement account and crediting the latter’s settlement account. Such banks are also known as direct settlement banks to distinguish them from banks which operate through agents. As already stated, a number of other FMIs including Bacs, the Faster Payments Service (FPS), Cheque and Credit Clearing and LINK settle through RTGS but unlike CHAPS they are not dependent on RTGS to process each individual transaction prior to release. These retail systems tend to settle at periodic intervals on what is sometimes described as a Deferred Net Settlement (DNS) basis.

Irrespective of the model used, it is underpinned by extensive legal documentation with DNS systems being collateralised. Conversely, CREST sterling utilises a mechanism whereby the BoE effectively earmarks central bank funds owned by CREST settlement banks in such a way that they are only available to fund payments made by a settlement bank during a CREST settlement cycle. This enables CREST to settle individual trades irrevocably in its books knowing that funds are available to enable settlement in the BoE RTGS system subsequently. In normal operation this process only takes a minute or two and is repeated continuously. However, in the event of a BoE RTGS outage, the process is of course disrupted and in that case CREST could continue to settle trades by recycling Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law .

liquidity in its own books until the BoE RTGS system recovers. The whole mechanism is underpinned by a legally binding contractual arrangement. The Bank of England Part 5 of the Banking Act 2009 (BA 2009) provides the statutory framework for the conduct of payment systems oversight by the BoE. BA 2009 sets out criteria for the recognition of interbank payment schemes that are systemically important, currently seven in number: Bacs, CHAPS, FPS, CLS (the foreign exchange settlement system), the payment arrangements embedded in CREST and the central counterparties operated by LCH.Clearnet Limited and ICE Clear Europe. Under BA 2009 operators of recognised payment systems are required “to have regard” to any principles and codes or practice published by the BoE (ss 188-9). No codes of practice have been published to date. However, in December 2012 the BoE, having consulted with Her Majesty’s Treasury, published (for the purposes of s 188 of BA 2009) the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMIs) issued by the relevant BIS committee (CPSS now CPMI) and the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO). The PFMIs seek to impose various obligations on FMIs, as encapsulated in 24 PFMIs, 18 of which are relevant to payment systems.

These PFMIs include (by way of example) the principle that an FMI should have a sound risk-management framework for comprehensively managing legal, credit, liquidity, operational and other risks (Principle 3), as well as PFMIs 15 and 17 which focus speciï¬cally on general business and operational risk respectively. The PFMIs also set out ï¬ve areas of responsibility for central banks such as the BoE (“the Responsibilities”). These include the Responsibility that “FMIs should be subject to appropriate and effective regulation, supervision, and oversight by a central bank, market regulator, or other relevant authority.” It might be contended that the PFMIs assume that the BoE will ensure the efficient operation of the RTGS system, since without a reliable RTGS system there can be no appropriate or effective supervision or oversight of those FMIs for which the RTGS system performs an integral function. However, it cannot be said that the Responsibilities as set out in the PFMIs have imposed statutory duties on the BoE (or any other duties recognised by English law). In particular, s 188 of BA 2009 makes it clear that any PFMIs that are published by the BoE (having obtained the Treasury’s prior approval) are ones to which “operators of recognised inter-bank systems [ie not the BoE itself] are to have regard in operating their systems”.

The Government’s Explanatory Notes to Important Payment Systems (a precursor to the PFMIs), the IMF concluded that the BoE had only “broadly observed” (rather than just “observed”) the Responsibility to ensure systems it oversees comply with the Core Principles, commenting (at p 12): “The BoE assesses the RTGS infrastructure against the Core Principles in an indirect and fragmented manner through its oversight of CHAPS (and other recognised systems that use it, such as CREST, FPS, and Bacs). However, not all activity in the RTGS is undertaken in regard to these recognised systems, and, given the importance of the RTGS infrastructure to the U.K. ï¬nancial system, a direct and uniï¬ed assessment would be beneï¬cial.” IMPLICATIONS OF THE FAILURE OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND RTGS SYSTEM Feature “...

it would appear that the BoE has determined that its RTGS system is not subject to what were the “Core Principles” (now replaced by the PFMIs)...” s 188 of BA 2009 make it clear that this provision is not intended to impose new obligations on the BoE itself: “Subsection (1) gives the BoE the power to publish PFMIs to which operators of recognised inter-bank payment systems must have regard in the operation of their systems. This formalises an aspect of the existing structure of oversight, under which the BoE currently expects payment systems to take account of the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems’ Core Principles for Systemically Important Payment Systems”. Whilst not imposing legal duties on the BoE, such principles are highly relevant as a touchstone for the assessment by interested parties (including international bodies such as the IMF) of the BoE’s success or otherwise in overseeing the FMIs which settle through the BoE’s RTGS system. Interestingly, in its July 2011 paper regarding the observance by CHAPS of the CPSS Core Principles for Systemically Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law The BoE’s response to this conclusion (p 15 of the same document) commented as follows: “RTGS is not an interbank payment system but an accounting infrastructure that supports some payment systems. It would therefore not be appropriate to assess RTGS against the CPSS Core Principles as they apply to Payment Systems. The Bank will, however, this year conduct a uniï¬ed assessment of RTGS based on its existing internal risk assessment, monitoring and management framework. That will be done at arms’ length as well as by line management.” Accordingly, it would appear that the BoE has determined that its RTGS system is not subject to what were the “Core Principles” (now replaced by the PFMIs), although it is unclear to what extent this narrow interpretation of the PFMIs is accepted beyond the BoE itself.

For example, the European Central Bank has determined February 2015 71 . IMPLICATIONS OF THE FAILURE OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND RTGS SYSTEM Feature that the euro RTGS system TARGET 2 should be required to comply with the PFMIs subject to certain public policy exceptions and TARGET 2 is currently being assessed by its overseer on this basis. Apart from the BoE’s PFMI Responsibilities, the BoE has entered into standard form “RTGS Account Mandate Terms and Conditions” with settlement banks (the “Terms and Conditions”). The Terms and Conditions regulate the rights and obligations as between the BoE and the RTGS “Account Holders” (ie banks wishing “... the Terms and Conditions do not impose any obligation on the BoE to ensure that the RTGS system is not interrupted...” to participate in the RTGS system). As regards the BoE’s obligations, the Terms and Conditions do not impose any obligation on the BoE to ensure that the RTGS system is not interrupted or that it operates in such a way as not to cause any loss to Account Holders. Clause 6.1(b) of the Terms and Conditions provides that: “[The Account Holder agrees and acknowledges that] the Bank, and its representatives and agents shall not be liable, save in the case of wilful default or reckless disregard of the Bank’s obligations, for any Loss arising directly or indirectly from the operation by the Bank of the RTGS Central System or the Collateral Management Portal or any interruption or loss of the RTGS Central Systems or the Collateral Management Portal or loss of business, loss of proï¬t or other consequential damage or any damage whatsoever and howsoever caused (including but without prejudice to the foregoing by reason of machine or computer malfunction or error and also any suspension or variation pursuant to clause 6.1(a) above).” Whilst the Terms and Conditions provide (for example) that the BoE is subject to a (qualiï¬ed) obligation to effect payment 72 upon receipt of appropriate instructions from an Account Holder (see in particular clauses 6.1(i) and (j)), they do not impose any express obligation on the BoE to ensure that the RTGS system is not interrupted or that it operates in such a way as not to cause any loss to Account Holders. In any event, clause 6.2(b) reflects the BoE’s statutory immunity from liability in damages provided by s 244 of BA 2009, which is limited to action or inaction by the Bank which is not in bad faith or in breach of s 6(1) of the Human Rights Act 1998. February 2015 In brief, therefore, it is difficult to see on what basis an RTGS Account Holder could seek legal redress against the BoE in respect of any RTGS system outage, notwithstanding that such an outage may have been caused by the BoE’s recklessness or even its wilful acts or omissions, on the basis (inter alia) that the BoE is under no legally enforceable obligation to ensure that the RTGS system operates correctly. CREST CREST sterling is the UK’s securities settlement system, operated by Euroclear UK and Ireland (EUI), which provides real-time Delivery versus Payment ultimately against central bank money for transactions such as gilts, equities and money market instruments.

It settles continuously throughout the day. Most settlements in CREST are in sterling and we consider these ï¬rst. CREST is remarkably well insulated from problems caused by an RTGS outage, and indeed continued to operate on 20 October 2014, without the serious problems experienced by CHAPS. Fundamentally, that is because the CREST system allows CREST to settle the transactions using “earmarked” central bank funds, but crucially without simultaneous access to the RTGS accounts (as described below). When RTGS operates normally, CREST settlements will be reconciled with RTGS about every two minutes.

But if there is an RTGS outage, it is possible, with BoE permission, for CREST in effect to continue to use the earmarked central bank funds to settle CREST transactions until RTGS is restored (recycling liquidity), and the CREST settlements can once again be reconciled with RTGS. The key feature of CREST is that delivery is made against payment. But payment here consists of a promise to pay by the settlement bank of the buyer. The buyer may be the customer of a settlement bank A and the seller the customer of settlement bank B.

The buyer discharges his obligation to pay the seller by the promise of his settlement bank A to pay settlement bank B. This promise happens at the moment of delivery of title. Settlement bank A then discharges that obligation to pay settlement bank B by the undertaking of the BoE to pay bank B. This also happens at the same time as the moment of delivery to the buyer. CREST then applies the payment by settlement bank A to bank B to its record of the Liquidity Management Account (LMA) for each bank.

In effect, the LMA is a part of the records of the BoE which is operated by CREST. The BoE earmarks funds available in its accounts to settlement banks, and in effect hands the earmarked funds to CREST. Earmarked funds may not be used other than for CREST settlements.

The settlement bank is only entitled as against the BoE to such part of the earmarked funds as CREST returns. Normally CREST will transmit details of the transactions on the LMA back to the BoE using RTGS about every two minutes. The accounts of the BoE are updated.

The cycle is then repeated with earmarked funds being allocated to CREST. In this way CREST is able to settle transactions for CREST members with the certainty of central bank funds, but without a simultaneous debit and credit on the RTGS system. Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law . If there is an outage, the BoE may permit CREST in effect to recycle earmarked funds in the LMAs during the period when CREST is disconnected from RTGS. CREST may continue despite the outage. During the disconnection period there is a mechanism for LMAs to be topped up if required. It is also possible for the recycling to be extended overnight if required. CREST also has euro and US dollar streams although they are much lower value than sterling. Euro also settles in central bank funds but through the euro RTGS system TARGET 2 using one of TARGET 2’s proprietary ancillary system interfaces. Access is through the Central Bank of Ireland. Conversely, the US dollar stream settles bilaterally between the settlement banks.

Although the mechanisms for sterling and euro differ, in both cases CREST settles trades with ï¬nality on its own systems before the ultimate transfer of funds is shown on RTGS. CHAPS CHAPS, or the “Clearing House Automated Payment System”, is a payment system operated by the CHAPS Clearing Company Limited which makes real time gross payments in sterling, settled through the BoE’s RTGS system on an individual basis before being executed. The CHAPS system is designed especially for high value and/or time critical payments, where immediacy of settlement and certainty are of paramount importance. Settlement members use SWIFT messages to communicate, with the SWIFT proprietary process holding the message and sending on the critical details to the BoE’s RTGS system. Settlement is effected across the RTGS system (and on the RTGS model) by the BoE debiting the paying settlement bank’s member’s account and crediting the payee settlement bank’s member’s account commensurately and in real time before the payment is released to the payee settlement member. The rights and obligations of the settlement members as regards their Procedural Documentation”. Where the settlement member acts for a customer – in using CHAPS, the customer may, as between himself and his settlement member, be bound by the usages of CHAPS: see Tidal Energy Limited v Bank of Scotland [2014] EWCA Civ 1107, applying “...

a customer might claim against his settlement member for breach of contract in failing to deal with a payment...” participation in the CHAPS system are provided principally by the CHAPS Rules, a set of rules drafted by the CHAPS Clearing Company Limited to which all CHAPS settlement members subscribe. In circumstances where the RTGS system fails such that CHAPS payments are unable to settle for a period of time, it is possible that a paying settlement member would be in breach of Rule 2.2 of the CHAPS Rules in circumstances where it had instructed a Payment but RTGS had failed and the payment had not been made. Under Rule 2.2, the settlement members must for the purposes of making payments through the CHAPS system: Hare v Henty (1861) 10 CBNS 65, 142 ER 374, 379. So too, a customer might claim against his settlement member for breach of contract in failing to deal with a payment for the customer in accordance with the CHAPS Rules.

The CHAPS Rules make it clear that only the settlement members are in contractual relations with each other. But that would not prevent a customer of a settlement member from relying on the terms of his contract with the settlement member, including an obligation to deal with the payment in accordance with the CHAPS Rules. “… accept and give same day value to all Payments [deï¬ned at Rule 1.1 as ‘a payment made through CHAPS (whether made under normal operation or effected as a Contingency Transfer) that satisï¬es the criteria listed in Rule 3.1’] denominated in sterling received within the timeframes set out in the CHAPS Timetable in the CHAPS IMPLICATIONS OF THE FAILURE OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND RTGS SYSTEM Feature Biog box Roger Jones is the Chairman of the TARGET Working Group which represents the European banking industry in discussions on the TARGET 2 payments system with the European Central Bank and other Eurosystem central banks. Email: jonesrsj@btinternet.com. Raymond Cox QC is a barrister practising from Fountain Court Chambers, London. Email: rc@fountaincourt.co.uk. Raymond warmly acknowledges the assistance of Alexander Riddiford of 3-4 South Square in the preparation of this article. What is payment in the 21st century? [2014] 11 JIBFL 675 Managing settlement risk in retail payment systems: the proposal to prefund daily payment exposures [2014] 7 JIBFL 462 Lexisnexis Financial Services blog: Payments regulation: the shape of things to come Further reading Is this your copy of Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law? No.

Then why not subscribe? Subscribe today on ly £946 JIBFL is the leading monthly journal providing practitioners with the very latest on developments in banking and ï¬nancial law throughout the world that is also practical, in tune with the industry, and easy to read – re-designed for you, the busy practitioner. Subscribe today and enjoy: Each issue contains more features and cases than ever plus an ‘In Practice’ section containing high value ‘know how’ articles. Your own copy, delivered direct to you, every month. www.lexisnexis.co.uk JIBFL keeps you right up-to-date with key developments relevant to international banking and ï¬nancial law. Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law February 2015 73 . THE SLENDER THREAD OF MODFIED UNIVERSALISM AFTER SINGULARIS 74 Feature KEY POINTS The existence of the common law power to assist foreign insolvency proceedings has been conï¬rmed by the Privy Council, but its scope has been signiï¬cantly curtailed. The power to assist does not extend to the application of powers analogous to those conferred by domestic legislation which would not otherwise apply to a foreign insolvency; nor does it enable office-holders to do something which they would not be able to do under the law by which they were appointed. The power to assist may extend to compelling the production of information in support of a foreign insolvency, but the scope of this power is uncertain. Authors Barry Isaacs QC and Andrew Shaw The slender thread of modiï¬ed universalism after Singularis This article considers the decision of the Privy Council in Singularis Holdings Ltd v PricewaterhouseCoopers [2014] UKPC 36 and its implications. THE PRINCIPLE OF “MODIFIED UNIVERSALISM”: CAMBRIDGE GAS AND HIH â– In Cambridge Gas Transportation Corporation v Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors of Navigator Holdings plc [2007] 1AC 508 (Cambridge Gas), Lord Hoffmann, giving the advice of the Privy Council, held that there is a common law power to provide such assistance to a foreign insolvency as could be given in equivalent domestic proceedings. Thus a plan approved by the US Bankruptcy Court could be given effect on the Isle of Man, despite it being neither a judgment in rem nor in personam. Such a plan could have been implemented in the Isle of Man under its Companies Act 1931 and could therefore be enforced without the need for parallel domestic insolvency proceedings. Cambridge Gas was authority for three propositions. The ï¬rst is the principle of modiï¬ed universalism (“the principle”), namely that the court has a common law power to assist foreign winding-up proceedings so far as it properly can. The second is that the principle permits the court to do whatever it could properly have done in a domestic insolvency, subject to its own law and public policy.

The third is that this power is itself the source of its jurisdiction over those affected, and that the absence of jurisdiction in rem or in personam according to ordinary common law principles is irrelevant. The ï¬rst and second principles were revisited by Lord Hoffmann in Re HIH Casualty and General Insurance Ltd [2008] 1 WLR 852 (HIH), in which he described February 2015 the principle as the golden thread running through English cross-border insolvency law since the 18th century. Lord Hoffmann said that the principle requires that English courts should, so far as is consistent with justice and UK public policy, co-operate with the courts in the country of the principal liquidation to ensure that all the company’s assets are distributed to its creditors under a single system of distribution. THE PRINCIPLE IN RETREAT: RUBIN The principle was given further impetus by the decisions of the Court of Appeal in Rubin v Euroï¬nance [2011] Ch 133 and Re New Cap Reinsurance Co Ltd [2011] 2 WLR 1095. Those decisions applied the principle to permit enforcement in England of avoidance judgments obtained in New York and Australia respectively.

These decisions were the high watermark for the principle. Just a few years after the principle was highlighted and developed by Lord Hoffmann in Cambridge Gas and HIH, its scope was curtailed by the decision of the Supreme Court in Rubin v Euroï¬nance [2013] 1 AC 236 (Rubin). The majority held that the same rules applied to the recognition and enforcement of judgments in personam, whether or not such judgments had been made in support of foreign insolvency proceedings. Accordingly, recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments in relation to preference or other avoidance proceedings were only permissible where the judgment debtor had been present in the foreign jurisdiction when proceedings commenced or where he had otherwise submitted to the jurisdiction of the foreign court. The Supreme Court held that, as a matter of policy, the rules governing recognition and enforcement should be no more liberal in relation to foreign avoidance judgments than any other foreign judgment. A different rule for avoidance judgments was unacceptable for four reasons.

First, there was no difference of principle between, for example, a foreign judgment against a debtor on a debt due to a company in liquidation and a foreign judgment for repayment of a preferential payment. Secondly, a different rule for insolvency judgments would not be an incremental development of existing principles, but a radical departure from settled law. The introduction of new rules for enforcement depends on a degree of reciprocity; and a change in the settled law has the hallmarks of legislation.

Thirdly, a different rule would be detrimental to UK businesses, because of the need to defend proceedings overseas. Fourthly, the rules in relation to recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments were not unjust: officeholders usually have remedies against defendants in the United Kingdom, either directly (by bringing proceedings in the UK) or indirectly (for example, by application of foreign law under s 426 of the Insolvency Act 1986; by applying local law under Art 23 of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency (“the Model Law”); or, where the insolvent has its centre of main interests in the European Union, by direct enforcement under Art 25 of the Council Regulation (EC) No 1346/2000 on insolvency proceedings). A majority of the Supreme Court (Lords Collins, Walker and Sumption) held in Rubin that Cambridge Gas was wrongly decided. Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law . Since Cambridge Gas was a judgment of the Privy Council and Rubin was a decision of the Supreme Court, the status of Cambridge Gas outside the English jurisdiction was not clear. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court did acknowledge the existence of a common law power to recognise and grant assistance to foreign insolvency proceedings. The principle also appeared to survive in areas other than recognition and enforcement. For example, in Re Phoenix Kapitaldienst GmbH [2013] Ch 61, Proudman J held that the English court had a common law power to provide a German administrator with relief identical to that available under s 423 of the Insolvency Act 1986, such relief not being otherwise available. The principle has also underpinned various statutory developments of English insolvency law. For example, the CrossBorder Insolvency Regulations 2006 (CBIR) incorporate the provisions of the Model Law into English law.

Following the decision in Pan-Ocean Co Ltd v Fibria Celulose S/A [2014] EWHC 2124 (Ch), the principle suffered a further setback. In that case, Morgan J held that the assistance which an English court can provide pursuant to Art 21(1) to Sch 1 of the CBIR is limited to relief available under English law. In this respect, the English approach to the application of the Model Law diverges from that taken in the USA. THE RETREAT CONTINUES: SINGULARIS Singularis Holdings Ltd was incorporated in the Cayman Islands and was subject to a winding-up order in that jurisdiction. The liquidators (“the liquidators”) sought the working papers of the company’s auditors, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) in Bermuda, which was the place of registration of the branch of PwC which had carried out the audits. Section 195 of the Companies Act 1981 of Bermuda allows the court, in respect of a company which the Bermuda court has ordered to be wound up, to summon before it any person deemed capable of giving information concerning the affairs of the company, and to produce any books and papers in his custody relating to the company.

The Supreme Court of Bermuda recognised the status of the liquidators and ordered PwC to produce documents and attend court for examination on the basis of a common law power “by analogy with the statutory powers” contained in s 195 of the Companies Act 1981. PwC successfully appealed against this order, and two points subsequently came before the Privy Council: jurisdiction, were expressly disapproved. Each member of the Board gave a separate judgment, in part because of how the case had been argued below. At ï¬rst instance and on appeal the liquidators’ primary case was that, in circumstances where the legislation did not apply, the foreign court nonetheless had a common law power to apply its own domestic legislation by analogy as though the foreign “Lord Collins said that the approach taken in Cambridge Gas, where the application of the statutory procedure for approval of a scheme of arrangement on the Isle of Man was held to be unnecessary, was wrong...” Did the Bermudan court possess a common law power to assist a foreign liquidation by ordering the production of information, in circumstances where the analogous statutory power could only be exercised in a winding-up and there was no jurisdiction to wind-up the company; and if such a power did exist, could it be exercised where an equivalent order could not have been made by the court in the Cayman Islands. On the second point the Board held that the Bermudan courts could not exercise a common law power to assist the winding up where the courts of the Cayman Islands had no such power. On the ï¬rst point, a majority (Lords Sumption, Collins and Clarke) held that there was such a power.

Lords Mance and Neuberger disagreed. The Board also held that Cambridge Gas was authority for the proposition that the court had a common law power to assist a foreign insolvency only as far as it properly could, in line with the principle of modiï¬ed universalism. The other propositions that the Board had derived from Cambridge Gas, namely that the common law power to assist includes doing whatever could properly be done in a domestic insolvency, and that this power is the source of the assisting court’s Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law insolvency were domestic. Argument concerning the existence of a common law power to order information only came to prominence in the hearing before the Privy Council. Lord Collins directed his judgment towards debunking the liquidators’ initial argument that the Supreme Court should apply s 195 by analogy as if the company were a Bermudan company.

He held that this involved a fundamental misunderstanding of the limits of the judicial law-making power. Lord Collins said that the approach taken in Cambridge Gas, where the application of the statutory procedure for approval of a scheme of arrangement on the Isle of Man was held to be unnecessary, was wrong; and that courts which had followed this approach had been wrong to do so. For example, Re Phoenix Kapitaldienst GmbH, in which Proudman J held that the power to use the common law to recognise and assist an administrator appointed overseas includes doing whatever the English court could have done in the case of a domestic insolvency, had been wrongly decided. Lord Sumption addressed the limits to the power to assist a foreign insolvency. He held that, in the absence of a statutory power, these must depend upon the common law; how far it would be appropriate to develop the common law did not admit of a single universal February 2015 THE SLENDER THREAD OF MODFIED UNIVERSALISM AFTER SINGULARIS Feature 75 .

THE SLENDER THREAD OF MODFIED UNIVERSALISM AFTER SINGULARIS Feature answer. He therefore only considered whether there was a common law power to order production of information in the absence of an equivalent statutory power. In his judgment there was a power to compel the production of information which is necessary for the administration of a foreign winding up. This was a development of the common law which was justiï¬ed as follows: (1) While the power of the English courts to compel the giving of evidence was solely statutory, the same did not apply to information. (2) In Norwich Pharmacal v Customs and Excise Commissioners [1974] AC 133, the House of Lords had recognised a common law power to order the production of information in certain circumstances. (3) If the common law power to assist consisted only of recognising the insolvent company’s title to its assets or the foreign office-holder’s agency, it would be an “empty formula”. Lord Sumption cautioned that “in recognising the existence of such a power, the Board would not wish to encourage the promiscuous creation of other common law powers to compel production of information.” The power to assist a foreign insolvency at common law should be subject to certain limits: It was only available to assist the officer of a foreign court with insolvency jurisdiction, or equivalent public officers. It was not available to enable such officers to do something which they would not be able to do under the law by which they were appointed. It was available only when it is necessary for the performance of the office-holder’s functions. Its exercise must be consistent with the substantive law and public policy of the assisting court, thus it would not be available to obtain material for use in litigation. Its exercise is conditional on the applicant being prepared to pay a third-party’s reasonable costs of compliance. 76 February 2015 Biog box Barry Isaacs QC and Andrew Shaw are barristers practising at South Square who specialise in insolvency and restructuring law.

Barry represented the liquidators of New Cap Reinsurance Corporation Ltd in the Supreme Court in the conjoined appeals in Rubin v Euroï¬nance SA; Re New Cap Reinsurance Ltd [2013] 1 AC 236. Email: barryisaacs@southsquare.com and andrewshaw@southsquare.com Lords Clark and Collins agreed that there was a common law power to compel the production of information, and in Lord Collins’ view this power was to be exercised for the purpose of “identifying and locating assets of the company”. Lords Mance and Neuberger disagreed. They foresaw problems with the need to make ï¬ne distinctions, which any application of the power would entail, for example between information and evidence. Lord Neuberger also felt that the logic of the Supreme Court’s approach in Rubin was that new common law powers founded on the principle of modiï¬ed universalism should not be invented by the courts. ANALYSIS AND IMPLICATIONS The thread of modiï¬ed universalism, so far as the common law is concerned, remains intact, but it is now a slender one.

In Rubin it was held that a change in the law relating to foreign judgments to apply a different rule in the context of insolvency was a matter for the legislature. In Singularis, it was held that it is not for the court to apply legislation by analogy as if it applied, even though it did not actually apply; this would be a plain usurpation of the legislative function. The Privy Council has overruled Cambridge Gas on all points save the uncontroversial proposition that courts have a common law power to assist a foreign insolvency. A court cannot assist a foreign insolvency by applying apparently inapplicable domestic legislation as if it did apply.

The most potent weapon available to the court to assist at common law has thus been removed. The Privy Council has given little guidance on the limits of the common law power to assist a foreign insolvency. It is possible to discern two broad approaches. The minority judgments of Lord Mance and Neuberger express caution towards any increase of the powers to assist in a foreign insolvency already available at common law: these being, in broad terms, staying proceedings or the enforcement of judgments and the use of the statutory powers of the court in aid of foreign insolvencies, for example the use of the ancillary liquidation procedure. In contrast, the majority support an incremental development of the power to assist, but without indicating the extent of any such development or the areas in which it might operate. The power to compel production of information is illdeï¬ned; the purposes for which the power might be exercised as described by Lord Sumption are much broader than those set out by Lord Collins. One limitation applied to this power is of general application, namely that an assisting court will not be able to provide relief at common law which would not be available in the country of the insolvency. This is a recognition of the fact that modiï¬ed universalism essentially envisages an extension of the jurisdiction of that court overseas, where that is compatible with local law and public policy.

Beyond this, however, and as was pointed out by Lord Mance, the scope of the common law assistance which may be provided to a foreign insolvency is uncertain. Lord Neuberger observed that the extent of the principle is a very tricky topic on which the Privy Council, the House of Lords and the Supreme Court had not been conspicuously successful in giving clear or consistent guidance – as evidenced by the judgments in Cambridge Gas, HIH and Rubin. Having regard to the divergence of opinions in the judgments in Singularis, and the general terms in which the majority judgments were expressed, the principle of modiï¬ed universalism still lacks clarity in its application, albeit that it is clear that its scope has been signiï¬cantly curtailed. Further reading What’s left of the golden thread? Modiï¬ed universalism after Rubin and New Cap [2012] 11 JIBFL 675 When will a court not assist a foreign insolvency proceeding? Recent experience in England, the US and Germany [2013] 3 JIBFL 159 Lexisnexis RANDI blog: R & I – pick of the cases in 2014 Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law .

Feature Authors Paul Downes QC and Emily Saunderson Foreign exchange manipulation: a deluge of claims? This article considers the prospects for litigation based on foreign exchange manipulation. â– Five banks were ï¬ned a record total of £1.1bn by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in November 2014 for failing to control business practices in their foreign exchange trading operations. Hefty ï¬nes were also levied by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency in the US, and the Swiss ï¬nancial regulator, FINMA. The FCA found that between 1 January 2008 and 15 October 2013, ineffective controls at Citibank NA, HSBC Bank Plc, JPMorgan Chase Bank NA, Royal Bank of Scotland Plc and UBS AG allowed foreign exchange (FX) traders in G10 currencies to put their employers’ interests above those of their clients, other market participants, and the wider UK ï¬nancial system. Customers of the banks will be concerned to know two things: ï¬rst, whether the wrongdoing would give grounds for a claim to rescind onerous currency transactions; and secondly, whether even without rescission the wrongdoing could form the basis of a claim for losses suffered as a result of the manipulation. The failings criticised by the FCA, and other national regulators, related to manipulation of the spot foreign exchange “ï¬xes”, which are key benchmarks used in the FX markets, although the ï¬nes were for failings in staff management rather than currency manipulation. The FCA’s Final Notices in respect of each bank ï¬ned describe how traders at a related claim off the ground than it is to build a LIBOR claim. THE FOREIGN EXCHANGE “FIXES” number of banks manipulated the price of foreign exchange rates before key spot rate ï¬xes in order to beneï¬t from trades their clients had speciï¬ed to be made at the ï¬x rate. The Final Notices also explain how the banks used internet chat rooms to share information to facilitate the collusion in moving FX rates to the banks’ advantage. Coming so soon after regulators unearthed manipulation by banks of the LIBOR benchmark, it is tempting to assume that similar potential claims arise from foreign exchange manipulation as were touted, and in a few cases pursued, in respect of the misstatement of LIBOR. Additionally, the size of the global FX markets (the latest ï¬gures suggest trades averaged $5.3tn per day)1 may lead to assumptions that manipulation must have led to huge customer losses. The FCA produced ï¬ve Final Notices, one in respect of its ï¬ndings for each of the banks upon which it imposed a penalty. The two benchmark ï¬xes mentioned in the FCA Final Notices are the WM/ Reuters 4pm UK ï¬x (“the 4pm WM Reuters Fix”), and the European Central Bank ï¬x at 1:15pm UK time (“the ECB Fix”). Unlike the way in which LIBOR is determined, neither the 4pm WM Reuters Fix nor the ECB Fix depends upon a number of panel banks submitting actual or indicative rates, and the process by which the ï¬nal rates are arrived at is not entirely clear. In its Spot & Forward Rates Methodology Guide, World Markets Company Plc (“WM”) says that certain portions of the methodology and related intellectual property used to calculate its FOREIGN EXCHANGE MANIPULATION: A DELUGE OF CLAIMS? KEY POINTS A review of the FCA’s ï¬ndings and an analysis of the difficulties of discerning and then proving a loss suggest that, if anything, it may well be even harder to get a foreign exchange-related claim off the ground than it is to build a LIBOR claim. Unlike the way in which LIBOR is determined, the process by which the ï¬nal rates are arrived at is not entirely clear. It seems that a customer could not claim for damages unless its speciï¬c currency contract was adversely affected by the wrongdoing. “World Markets Company Plc says that certain portions of the methodology and related intellectual property used to calculate its rates are proprietary and conï¬dential...” Some commentators have predicted a “tidal wave” of civil litigation in relation to foreign exchange manipulation, and that it should be much easier for market participants to prove that they lost money.2 However, a review of the FCA’s ï¬ndings and an analysis of the difficulties of discerning and then proving a loss, suggest that, if anything, it may well be even harder to get a foreign exchange- Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law rates are proprietary and conï¬dential, and are not therefore publicly disclosed. WM does say that it determines the relevant ï¬x by taking transactional data entered into electronic trading platforms, including bid and offer rates and actual trades, over a one-minute period from 30 seconds before to 30 seconds after the ï¬x at 4pm UK time. WM may use its own judgment to assess the validity of rates, and it has guidelines and procedures to February 2015 77 .

FOREIGN EXCHANGE MANIPULATION: A DELUGE OF CLAIMS? Feature govern the application of its judgment. The median bid and offer rates are calculated using valid rates from the ï¬x period, and the mid-rate is calculated from the median bid and offer rates, resulting in a mid-trade rate and a mid-order rate. A spread is then applied to calculate a new trade rate bid and offer and a new order rate bid and offer, and the new trade rates are used, in a way which is not speciï¬ed by WM, for the ï¬x. The procedure for calculating the ECB Fix is even more opaque. The ECB says its FIX is “based on the regular daily concentration procedure between central banks within and outside the European System of Central Banks”, and although it purports to publish the methodology on its website, 3 none of the underlying documents were, at the time of drafting this article, accessible.

The ECB rate is said by the FCA to reflect the rate at a particular moment in time each day, which is usually around 1:15pm UK time. rate), and the ï¬x rate is higher than the average market rate at which the bank sells the same quantity of that currency in the market (not at the ï¬x), the bank will make a loss. In managing its own exposure, a bank may affect the ï¬x inadvertently. But if a bank is able to manipulate the relevant ï¬x rate depending on the direction of its net client orders, it can proï¬t from its clients’ positions. It appears that the manipulation occurred by the banks co-ordinating the timing of transactions so as to push the price in a desired direction shortly before the ï¬x. Concerted efforts of this sort amount to clear market abuse.

However, it is important to appreciate that this is wrongdoing of a different order to that involved in the LIBOR manipulation: there panel banks deliberately understated or overstated returns as to what rate they would be prepared to lend at on the interbank market. “... it seems that a customer could not claim for damages unless its speciï¬c currency contract was adversely affected by the wrongdoing” THE MANIPULATION Where a bank trades with its customer at the ï¬x rate, it does not charge commission on the transaction or act as an agent; it trades with the customer as a principal. 4 The bank in such a situation is therefore exposed to foreign exchange rate movements at the ï¬x because: (a) If the bank has net client orders to buy EUR/USD at the ï¬x rate (ie the bank will be a seller of euros to its clients in exchange for dollars at the ï¬x rate), and the ï¬x rate is lower than the average rate at which the bank has agreed to buy Euros in the same quantity in the market (not at the ï¬x), the bank will make a loss. (b) Alternatively, if the bank has net client orders to sell EUR/USD at the ï¬x rate (ie the bank will buy euros from its clients in exchange for dollars at the ï¬x 78 February 2015 Each FCA Final Notice gives one example of the relevant bank’s attempts to manipulate the ï¬x.

None of the FCA examples include dates, which makes it difficult if not impossible for potential claimants to know if their trades are likely to have been affected. The example used in the FCA Final Notice for Citibank describes a situation where the bank had net client buy orders at the ECB Fix in the EUR/USD currency pair. So, Citibank would be a net seller of Euros to its clients in exchange for US dollars at the ï¬x, and it would beneï¬t if the ECB Fix for EUR/USD was higher than the average rate at which it bought EUR/ USD in the market (not at the ï¬x). Citibank’s net client buy orders at the ï¬x were €83m. By working with three other ï¬rms, Citibank increased the volume it would seek to buy for the ï¬x to €542m, which was clearly well above what it needed to manage its own exposure.

During the period from 1:14:29pm to 1:15:02pm, Citibank bought €374m, which accounted for 73% of all purchases on the EBS electronic trading platform during that period. At 1:14:45pm the EUR/USD offer rate was 1.32159. By 1:14:57pm, the offer rate was 1.32205, and the ï¬x was 1.3222. The FCA says that Citibank’s trading in this example made the bank a proï¬t of US$99,000. 5 RELEVANT WRONGDOING There can be little doubt that the banks’ actions described in the FCA Final Notices were wrongful.

They represent the clearest possible breach of the entire basis for currency dealing (ie that the rates at which the currency is traded are true market rates). The wrong could be advanced as a breach of an implied term in the agreement in question, or a misrepresentation, a tortious wrong, or anti-competitive conduct. In such circumstances the parties to speciï¬c transactions could claim damages for the extent to which they were prejudiced. However, such claims face three principal difficulties: First, it is far from clear that there was a huge volume of transactions which were tainted by the above wrongdoing. Secondly, the relevant manipulation appears to have been transaction speciï¬c; unlike LIBOR where the manipulation was directed at the benchmark itself, and for signiï¬cant periods it was clear that the benchmark was being artiï¬cially depressed.

Thus, from the information published by the FCA, it seems that a customer could not claim for damages unless its speciï¬c currency contract was adversely affected by the wrongdoing. Thirdly, the extent of the manipulation appears to have been far smaller. In the Citibank example cited above, the manipulation resulted in a movement of one hundredth of one percent with the result that the net proï¬t for the bank in a multi-million euro transaction was just short of one hundred thousand dollars. Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law . Of far more signiï¬cance would be a claim for rescission of the sort advanced in the Graiseley Properties v Barclays Bank Plc, and Deutsche Bank AG v Unitech Global Ltd cases. Both Graiseley and Unitech began life essentially as interest rate swap misselling cases. They were amended to include implied misrepresentations by the banks as to LIBOR, which it was said gave rise to the right to rescission. Parties to an onerous currency swap, or other currency transaction, might seek to rescind on the ground that the transaction was entered into on the basis of a representation (express or implied) that the currency exchange rates that the bank was applying were true market rates and that the bank had not previously engaged in any manipulative activity. The banks are likely to point out that, unlike LIBOR, the manipulation here was very much more restricted in scope and therefore any implied representation that the bank’s rates were true market derived rates was true; and that the limited examples from the FCA notice were isolated incidents which did not prejudice the individual client’s trades. Additionally, the difficulty of proving that any given currency transaction was tainted by manipulation appears more signiï¬cant than in LIBOR-related claims because of the lack of information about speciï¬c wrong-doing in the FCA Final Notices. CONCLUSION The wrongdoing found by the FCA appears to have been less extensive than that connected with LIBOR manipulation. Thus it would be reasonable to assume that the resultant litigation would be unlikely to exceed that which has arisen from the LIBOR debacle.

In that case, the claims have essentially been repackaged mis-selling claims with LIBOR manipulation added as an additional ground to attack the product concerned. It may well be that currency manipulation will go the same way, with only a limited impact on the scale of this particular class of litigation. 1 See the Triennial Central Bank Survey from the Bank for International Settlements, published in September 2013, which describes FX business as of April 2013. 2 See, for example, “Litigation deluge set to follow record forex ï¬nes”, Law Society Gazette, 12 November 2014. 3 http://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/browse. do?node=2018779. 4 See, for example, the FCA Final Notice in respect of UBS AG, dated 11 November 2014, at App B para 3.3. 5 See the FCA Final Notice for Citibank at paras 4.38 to 4.44. FOREIGN EXCHANGE MANIPULATION: A DELUGE OF CLAIMS? Feature Biog box Paul Downes QC heads the 2 Temple Gardens banking & ï¬nance group. He is recommended by Chambers and Partners, Legal 500 and Legal Experts as a leading practitioner in the banking & ï¬nance ï¬eld.

He was counsel for the claimant in Titan v Royal Bank of Scotland [2010] 2 LLR 92 and has acted and advised on many LIBOR-related claims. Email: pdownes@2tg.co.uk. Emily Saunderson is a barrister practising from 2 Temple Gardens, Temple, London.