Crowded Skies: Opportunities and Challenges in an Era of Drones – March 31, 2015 - ( White Paper )

Reed Smith

Description

. PREFACE

When I recently attended the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, two things struck me as

game changers – 3-D printers and commercial drones. While the 3-D printers are still a novelty

item for most, the commercial and private applications of drones was spellbinding. From drones

as small as a quarter that flew overhead in swarms like flies, to those five feet or more across, the

potential uses seemed limitless. The era of drones for personal entertainment was the least

exciting part of the show.

The myriad ways they’re being used to film, deliver, monitor and touch our lives in so many ways impressed me as transformative to the way we do business. It also struck me that drones pose serious legal issues as well, many of which have been overlooked or ignored at the operator’s peril. From that moment at CES, my fellow authors and I decided to explore the way drones impact the day-to-day lives of corporations, organizations and individuals using them, and those who are being targeted. This white paper – Crowded Skies: Opportunities and Challenges in an Era of Drones – explores the legal ramifications and risks of drones in a variety of disciplines, including: ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· ï‚· Advertising and Promotion Aviation – Regulatory Copyright Employment and Labor Export Controls Film and Television Insurance and Insurability Music Privacy Product Claims and Litigation This is a truly collaborative work with contributions from 22 of my Reed Smith colleagues. It all came together with the help of Co-Editor Ross Kelley, who tirelessly worked on editing and compiling.

Thanks to all of them. As the legal environment surrounding drones evolves, this white paper will evolve as well to offer a comprehensive, up-to-date resource. Subsequent editions containing new and updated chapters will be released, so please be on the lookout for them. We hope that Crowded Skies: Opportunities and Challenges in an Era of Drones provides readers with valuable guidance as they take to the skies, and we welcome any comments or questions. Douglas J. Wood Editor .

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Advertising & Promotion ................................................................................................................................ 1 Aviation - Regulatory ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Copyright (EU) ............................................................................................................................................. 11 Employment and Labor................................................................................................................................

13 Export Controls ............................................................................................................................................ 14 Film and Television (UK) ............................................................................................................................. 19 Film & Television (U.S.) ...............................................................................................................................

23 Insurance and Insurability ............................................................................................................................ 26 Music ........................................................................................................................................................... 33 Privacy (U.S.) ..............................................................................................................................................

35 Privacy (UK) ................................................................................................................................................ 43 Product Claims and Litigation ...................................................................................................................... 47 Biographies of Editors and Authors .............................................................................................................

51 Endnotes ..................................................................................................................................................... 58 Appendices .................................................................................................................................................. 63 .

-- CHAPTER 1 -Advertising and Promotion Chapter Authors Keri Bruce, Associate – kbruce@reedsmith.com Matthew Kane, Associate – matthew.kane@reedsmith.com Sulina Gabale, Associate – sgabale@reedsmith.com “Drone-vertising” “Is this science fiction or is this real?” This was a question posed by Amazon after the debut of a promotional video touting Amazon’s upcoming drone delivery service, PrimeAir. 1 In the video, a tent-like drone sweeping through suburbia delivered a skateboarding tool to a father and daughter in less than 30 minutes. This promotional video, cleverly released around the holiday season, created buzz around PrimeAir and raised many questions about the legitimacy of the service. With the proliferation of drone usage in the military, film industry and for emergency response, entrepreneurs all around the world are starting to incorporate drones in advertising and marketing tactics to consumers. The use of drones in advertising – nicknamed, “drone-vertising” – is an industry in the making. Current Advertising Practices Using Drones Companies The first company to exclusively specialize in drone-vertising was a Philadelphia-based company named DroneCast, started by 19-yearold founder and CEO, GauravJit Singh.2 DroneCast’s services include using drones to publicize grand openings, running promotional activities, and deploying location-based drones to advertise to a specific client base via aerial advertising platforms, which, essentially, act as a flying billboard.

The drone operators use an iPad app to plot a route on a Google Maps-like Advertising and Promotion program by selecting the altitude and speed. Ad space using DroneCast is likely to run a customer an average of $3,000 per hour for a six-foot-long, two-foot-wide banner hovering about 25 feet off the ground.3 Though the company is still hashing out safety protocols and has not received regulatory approval, DroneCast’s advertising tactics may likely set the tone for future drone advertisers. International Use Developments in drone-vertising are also being made overseas, sometimes at a faster rate than in the United States, because of restrictive Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) standards on the commercial use of drones. For example, a Russian creative agency, Hungry Boys, created a new advertising technique for the popular Moscow noodle restaurant, Wokker, which incorporated the use of banners attached to drones.4 The drones advertising Wokker were programmed to fly around a number of high-rise buildings in Moscow’s financial district at lunchtime, attracting the attention of hundreds of hungry workers.

After the campaign launched, Wokker deliveries in the targeted areas jumped 40 percent.5 Coca-Cola put its own twist on drone-vertising in an advertisement shot in Singapore. The soda brand teamed up with the nonprofit Singapore Kindness Movement to deliver care packages to migrant construction workers.6 The care packages included photos of Singapore citizens holding signs thanking the workers and, of course, included cans of Coca- 1 . Cola. Ad agency Ogilvy & Mather Singapore distributed the online ad with the hashtag #CokeDrones.7 Promotions Drones may also be used in promotions, sweepstakes and contests. For example, a Philadelphia-based dry cleaner is attempting to run a loyalty program by selecting a monthly customer who will have his/her clothes delivered via drone for free.8 Such promotional activities, designed to enhance business, exposure and customer loyalty, could potentially flourish with the use of drones. Not only could drones reach a wider audience of consumers in otherwise isolated locations, but they could also increase brand interaction with the opportunity to provide promotions to consumers through delivery services (as we have seen with Amazon PrimeAir), freebies, etc. Location-Based Advertising In recent years, there has been a sharp increase in the use of location-based marketing in the United States.

In 2010, businesses spent $42.8 million on location-based marketing.9 That figure was projected to rise to $1.8 billion by 2015.10 Location-based advertising is targeting ads to consumers based on their physical location (similar to its counterpart, behavioral advertising, which targets ads to consumers based on their Internet usage). Though these forms of advertising are becoming increasingly popular, they also raise concerns with regard to the collection and use of consumer data, such as names, ages, addresses, health and other personal information. The potential use of drones as marketing tools that can track down and follow consumers to deliver advertising or monitor consumer movement in real-time may further heighten such concerns over consumer privacy. Advertising and Promotion Social Media and User-Generated Content In addition to using drones to display advertising, various emerging companies are using drones to create advertising – especially in regard to capturing photo/video, user-generated content, and for social media.

Production company Freefly Cinema uses drones affixed with highquality cameras for aerial shots in ads for brands such as Honda, Dodge, FedEx and REI.11 Similarly, a video content team called Corridor Digital used the popular DJI Phantom 2 quadrocopter affixed with a GoPro camera to film aerial footage of Los Angeles in March 2014. The resulting clips were used to create a video called “Superman With a GoPro,” which went viral and racked up 12.6 million views in just two months.12 Drones will allow advertising agencies to capture seemingly unprecedented shots for a number of advertising objectives – from producing commercials to capturing the crowd at an event. Drones may also allow advertisers to capture potentially dangerous footage in isolated areas because of the unmanned nature of its use and the size/weight of a typical drone. Just as we have seen with the PrimeAir promotional video, footage captured on drones has the potential to go viral on the Internet and throughout social media. Not only are drones likely to expand possibilities for advertisers, but they may also be used in creating usergenerated content (“UGC”) by any individual. Prices for a drone range anywhere from $70 to $4,000, depending on its quality and intended use.

Consumers are buying them as Christmas presents, as toys, and as their very own remotecontrolled aerial camcorders. The availability of drones to the mass public allows for any individual to create his or her own content through information gathering and capturing photo/video. Though this likely does not affect any current regulations for social media and UGC, the availability of drones creates the opportunity for any individual to gather and create unprecedented viral videos and/or photos at a potentially low price point. 2 .

Legal Framework FAA Regulation and Authority Although drone-vertising can be an extremely effectively tool for marketers, the legality of using drones for commercial purposes has come into question. In 2011, the FAA fined Raphael Pirker $10,000 for flying a drone around the University of Virginia campus.13 Pirker had been hired to take videos and photographs of the campus for an advertising agency. The FAA alleged that Pirker had violated certain provisions of Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs), which prohibit the operation of “aircraft” in a careless or reckless manner so as to endanger the life or property of another.14 In March 2014, a National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) administrative law judge vacated the fine, finding that Pirker’s Ritewing Zephyr remote-controlled plane was not the type of “aircraft” subject to the FARs, and that the FAA had not issued an enforceable FAR regulatory rule governing model aircraft operation15. The FAA appealed the decision, and on November 18, 2014 – in a unanimous decision – the NTSB reversed the findings of the administrative law judge.16 The NTSB concluded that (1) Pirker’s drone qualifies as an “aircraft” subject to FARs, and (2) Pirker’s drone is subject to the FARs prohibiting the operation of an unmanned aircraft system (UAS) in a careless and reckless manner.17 Although Pirker recently settled with the FAA18, the NTSB decision represents a giant win for the FAA and a significant setback for companies like DroneCast. FAA Current Practice Model Aircraft Operations Just three months after the initial decision in favor of Pirker, the FAA published a notice to clarify its position on model aircraft use.

Entitled “Interpretation of the Special Rule for Model Aircraft,” the notice set forth criteria that model airplane operators could follow in order to be exempt from FAA action.19 First and foremost, Advertising and Promotion the FAA clarified that model aircraft operations must be for hobby or recreational purposes only. The notice provided several examples of flights that would not be considered hobby or recreational: delivering packages to people for a fee, receiving money for demonstrating aerobatics with a model aircraft, and photographing a property or event and selling the photos to someone else. The FAA has also set forth safety guidelines for individuals flying model aircrafts20: • Fly below 400 feet and remain clear of surrounding obstacles • Keep the aircraft within visual line of sight at all times • Remain well clear of and do not interfere with manned aircraft operations • Don't fly within five miles of an airport unless you contact the airport and control tower before flying • Don't fly near people or stadiums • Don't fly an aircraft that weighs more than 55 lbs. • Don't be careless or reckless with your unmanned aircraft – you could be fined for endangering people or other aircraft Civil Operations Individuals who fly a UAS within the scope of the parameters set forth above would not need permission to operate their UAS; however, the FAA has stated that any flight outside the parameters – such as flying an aircraft heavier than 55 lbs. or flying a UAS for any non-hobby, non-recreational purpose – requires FAA authorization.

There are currently two methods of gaining FAA authorization to fly UAS.21 The first is to apply for a section 333 Exemption from the FAA. This process may be used by UAS 3 . operators to perform commercial operations in low-risk, controlled environments. The second is to apply for a Special Airworthiness Certificate from the FAA. This process may be used for civil aircraft to perform research and development, crew training, and market surveys. FTC In addition to FAA oversight, using drones may also implicate various FTC laws aimed at protecting consumers from misleading ads. For example, the FTC requires that an advertiser disclose to consumers any important information or conditions that may impact their decision to purchase a product or service.

In doing so, advertisers must meet the “clear and conspicuous” standard, where disclosures should use clear and unambiguous language that visibly stands out in the advertising – consumers should be able to notice disclosures easily; they should not have to look for them. In September 2014, the FTC targeted more than 60 national advertisers in print and television to warn them to comply with proper disclosure standards in what the FTC called “Operation Full Disclosure.”22 Because of the inherent mobile nature of drones and the distance from which they may deliver advertising to consumers, proper disclosures may be hard to achieve. In the case of DroneCast’s banner ads flying at a distance of 25 feet, proper disclosures for promotions would need to be in very large font, and the drone would likely have to hover at a much slower speed in order for a consumer to be able to read any conditional language. writing.

How exactly does an advertiser (or a consumer participating in a UGC promotion) obtain permission for use of a person’s image captured by a drone when that person did not initially consent to having his or her image captured? This will be something advertisers and their producers will have to consider when developing their production plan. The Bottom Line As this chapter has pointed out, the use of drones in advertising is potentially a booming business and is likely here to stay. Despite the proliferation of drone-vertising methods and tactics, however, marketers must be mindful of the legal ramifications when dealing with such usage. The FAA Modernization Reauthorization and Reform Act of 2012 requires the FAA to develop a plan for integration of civil UAS into the National Airspace System (NAS).23 Although the FAA did not meet its initial timeline for publishing a UAS Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM), on February 15, 2015, the FAA set forth an NPRM that would allow routine use of certain small UAS into the NAS.24 In addition to the current guidelines and requirements set forth in this chapter, marketers should review the NPRM and stay on top of any updates with this proposed legislation. Rights of Privacy and Publicity Finally, using drones may also bring privacy and publicity issues into play when video footage of unsuspecting individuals is used for commercial purposes, such as in advertising or in UGC.

The right of privacy and publicity generally prohibits the use of a person’s name or likeness for commercial purposes without permission, and, in some states, this permission is required to be in Advertising and Promotion 4 . -- CHAPTER 2 -Aviation - Regulatory Chapter Authors Patrick E. Bradley, Partner - pbradley@reedsmith.com Courtney Bateman, Counsel - cbateman@reedsmith.com On October 17, 2011, Raphael Pirker (aka “Trappy”) flew a Ritewing Zephyr powered glider (aka “drone”) over the campus of the University of Virginia. The drone was equipped with a camera, and the resulting video, for which Trappy allegedly was paid, is dramatic. The drone flies at low altitude through the populated UVA campus, zooming down streets, under a skywalk, through a tunnel, and even into a hedge.

The drone also flew extremely high, and in the vicinity of an active heliport. Through much of the flight, there could not have been visual line-of-sight contact between the drone and the operator. The Federal Aviation Administration got wind of the flight, setting the stage for a midair collision between the then largely unregulated world of drone operations and the pervasively regulated world of aircraft.

The FAA issued an order of assessment against Pirker, seeking a civil penalty of $10,000. According to the FAA, Pirker was in violation of section 91.13 of the Federal Aviation Regulations prohibiting “careless or reckless” operation of aircraft.25 Pirker moved to dismiss the FAA’s complaint, arguing essentially that the drone in question was a “model aircraft” and not an “aircraft,” and therefore the FAA had no authority to impose restrictions or seek a civil penalty in connection with his flight. other than voluntary guidelines that would not support the imposition of a civil penalty. On March 6, 2014, Administrative Law Judge Patrick G. Geraghty agreed with Pirker, and vacated the assessment. The ALJ considered the prior regulatory framework and observed that drones such as the one flown by Pirker had always been treated as “model aircraft,” and not “aircraft,” and that there simply were no regulations limiting the operation of model aircraft Model Aircraft Aviation - Regulatory The FAA appealed the ALJ decision to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), which, this past November 18, 2014, reversed the ALJ.

The NTSB found that Pirker’s drone, and all other drones, meet the definition of an “aircraft,” placing them within the FAA’s regulatory purview. The NTSB also found that the FAA’s application of 14 C.F.R. section 91.13(a) to drones is a reasonable interpretation of the regulation.

Pirker settled his civil penalty action with the FAA, but the matter remains significant in that it establishes the FAA’s right to regulate the operation of drones, even if the agency had yet to establish such regulations. As will be discussed in depth below, the FAA has proposed regulations for the commercial operation of small unmanned aircraft systems (sUAS). Until those regulations go through the comment period and are adopted – a process that could take months and even years – the operation of commercial drones will remain a regulatory no-man’s land, necessitating waivers from compliance with Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations, a body of rules designed to regulate manned aircraft and not drones. Historically, drones have been divided into two categories for regulatory purposes: “model aircraft,” and “everything else.” Over the years, the FAA has left modelers and recreational drone pilots alone for the most part.

The FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (P.L. 11295) (the Act) formalized the arrangement. Under 5 .

section 336 of the Act, a model aircraft is an unmanned aircraft that is (1) capable of sustained flight in the atmosphere; (2) flown within visual line of sight of the person operating the aircraft; and (3) flown for hobby or recreational purposes. The FAA may not promulgate regulations for model aircraft as long as certain requirements are met. Generally speaking, they must be limited to recreational use, they must be operated pursuant to a “community based set of safety guidelines,” the aircraft must weigh 55 pounds or less, they must not interfere with manned aircraft, and they may only be operated within five miles of an airport “if notice is provided to the airport operator or the tower.”26 Section 333 Exemptions Regulation of commercial unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) is a more complex matter. Because the current regulatory scheme is oriented toward the use of “manned” rather than unmanned aircraft, obtaining approval for nonrecreational uses has required case-by-case review pursuant to section 333 of the Act to determine whether a particular proposed UAS operation is safe. The review, referred to as the Section 333 Exemption process, requires that those entities that seek to fly UASs for commercial reasons, demonstrates to the FAA that their operations will either meet applicable regulations, or provide an equivalent level of safety (ELOS) for any certification regulations they cannot meet. For example, 14 C.F.R.

section 91.119(b) sets forth minimum safe altitudes for operation of aircraft, and prohibits aircraft in congested areas from flying less than 1,000 feet above, or 2,000 feet laterally from, the highest obstacle.27 Many operators seek to use sUAS to inspect wind turbines, flare stacks and similar structures, which of necessity involves flying much closer than allowed by the regulation. To do so, the operator must demonstrate that its proposed operations provide a level of safety (with regard Aviation - Regulatory to people, structures and other aircraft) equal to the regulatory requirement. To demonstrate an ELOS, the FAA usually places limits on altitude, requiring stand-off distance from clouds, permitting daytime operations only, and requiring that the UAS be operated within visual line of sight (VLOS) and yield right of way to all manned operations. The exemption provides that the operator will request a notice to airmen (NOTAM) prior to operations to alert other users of the national airspace system (NAS).

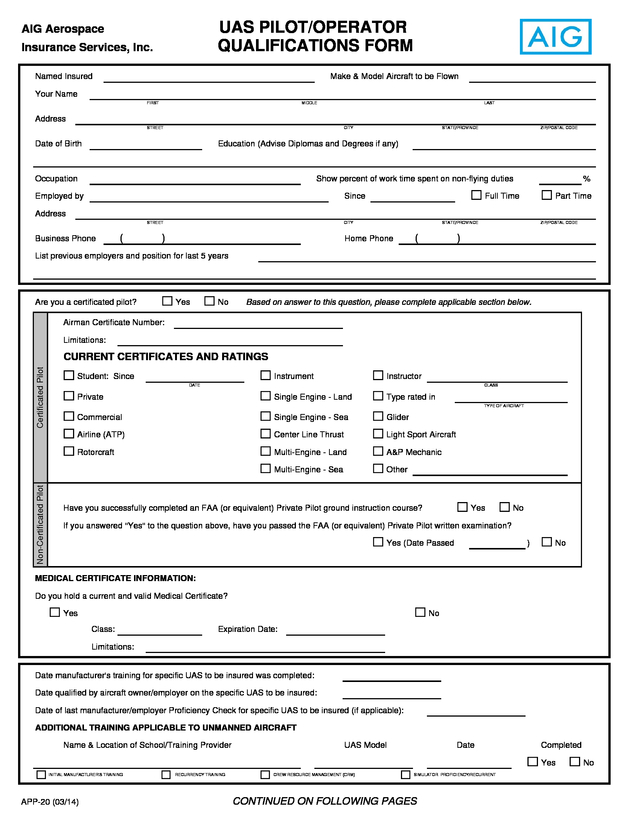

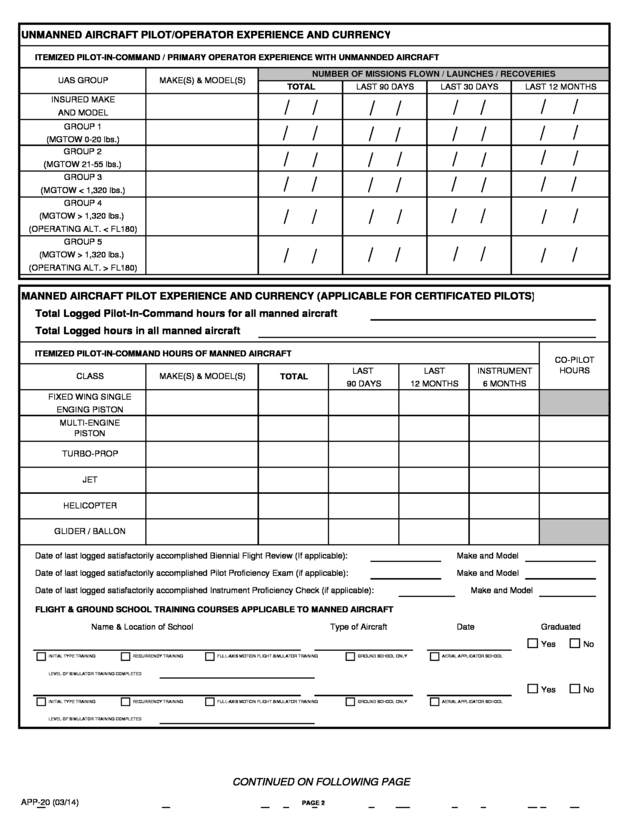

In addition, the FAA currently requires all operations to be conducted by a licensed private pilot with a current medical certificate. The FAA also requires that the pilot have a certain amount of experience flying UASs before conducting commercial operations, as well as three take-offs and landings within 90 days for currency purposes. During training flights, the pilot must comply with the minimum safe altitudes and distances described in 14 C.F.R. section 91.119. The FAA also is requiring operators who have received an exemption to coordinate with local air traffic control (ATC) facilities to obtain a Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA) for each specific operation.

The COA will require the operator to request a NOTAM, which is the mechanism for alerting other users of the NAS to the UAS activities being conducted. More information regarding the exemption process is located here. A list of companies that have been granted exemptions, along with a link to the grant, can be found here.

Exemptions granted to date involve aerial photography of real estate, closed set filming, precision agricultural surveys, bridge inspections and flare stack28 inspections. The Proposed Part 107 Recognizing that the current regulatory framework is unacceptable, and having received a mandate under the Act to create regulations allowing for the safe integration of unmanned aircraft into the NAS, the FAA unveiled a 6 . proposal for rules that would regulate routine civil operation of small UAS (sUAS), and to provide safety rules for those operations29. The proposed rule would be incorporated into Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations as new Part 107, limited to UASs below 55 pounds. The new rules would not apply to UASs above 55 pounds, thereby leaving potential operators such as Amazon in the section 333 limbo for the foreseeable future. With respect to sUAS operators, however, the new rules addressed – in a rational manner – the key regulatory issues of collision risk, ground personnel safety, operator certification and responsibilities, and aircraft requirements. See and Avoid Aircraft operating in the NAS currently are required to visually avoid other aircraft unless they are in instrument conditions and on an instrument flight plan.

Collision avoidance systems and traffic advisory systems have become common in commercial and some general aviation aircraft, and the availability of transponders permits ATC to observe the location and altitude of most aircraft, and to provide traffic advisories to aircraft communicating with ATC. Because they are small and are not equipped with transponders, drones are effectively invisible to ATC radar, and to pilots of other aircraft, manned and unmanned. Accordingly, the only effective way to avoid a collision between an sUAS and an aircraft is to maintain vertical and horizontal separation. The FAA’s proposed section 107 attempts to achieve this by segregating aircraft and drones to the extent possible, and by imposing on sUAS operators line-of-sight rules to mitigate collision hazards. Small UAS operation will be limited to an altitude below 500 feet above the ground level (AGL). The altitude is significant because, except when taking off or landing – or over water or sparsely populated areas – aircraft are prohibited from flying below 500 feet AGL.

Drones also will be Aviation - Regulatory prohibited from flying in class A, B, C, D, and E airspace without ATC permission. While these airspace designations are complex, the practical effect of the limitations is to prevent operation within five nautical miles of an airport or above 18,000 feet without permission. It is unclear at this time how the permission is to be obtained, how long it will take, and what limitations will be imposed upon the approvals. The proposed regulations require constant VLOS between the operator and the sUAS.

This is one of the most significant operational limitations on the commercial use of sUAS and was imposed because the FAA concluded that, given the current state of technology, it would not be possible to sufficiently mitigate the risk of collisions for sUAS outside the visual line of sight of the operator. In keeping with this requirement, sUAS operations are limited to daytime operation only,30 and flight visibility must be no less than three statute miles. Small unmanned aircraft may not fly closer than 500 feet below a cloud or 2,000 feet horizontally.31 Visual line of sight means that the drone operator must be able to see the sUAS at all times without any vision aid other than corrective lenses. Binoculars and, more importantly, onboard cameras, are not permitted to substitute for actual visual contact.

The FAA has not prohibited the use of onboard cameras, first-person view, or even binoculars, as long as at least one person involved in the operation has retained unenhanced visual line of sight with the sUAS. The proposed rules permit the use of a visual observer (VO), but the intent is that the observer will serve as an extra set of eyes to enhance separation, and not as a means to extend the range of the operation.32 If a tree or structure separates the drone and the operator, then VLOS has been lost, even if a VO can still see the drone. In addition, the responsibility of the operator is to ensure that the VO is able to see the sUAS as well. Finally, the operator and the VO must maintain “effective communication” with 7 .

each other at all times.33 Effective communication is not defined, but the FAA explains in the NPRM that the operator and visual observer must work out a method of communication prior to the operation that allows them to understand each other during the operation. According to the FAA, the proposed communication requirement would permit the use of communication-assisting devices, such as radios, to facilitate communications. The visual observer is not permitted to manipulate the controls of the sUAS, he is not considered an “airman,” and the VO is not required to obtain an airman certificate. The risk of collision with other aircraft is intended to be reduced by limiting the speed of sUAS to 87 knots.34 Whether this speed limitation will enable pilots of manned aircraft to avoid collisions is questionable, particularly in light of the small profile of the sUAS. In light of this, the proposed rules will require the sUAS operator to yield the right of way to other aircraft.35 If a manned aircraft comes into proximity with an sUAS, the pilot will not likely see the sUAS in sufficient time to take evasive action.

Under the proposed rule, therefore, the sUAS may not pass over, under or ahead of the other aircraft unless the other aircraft is well clear. Ground Personnel Safety In addition to concerns over collisions with other aircraft, the proposed Part 107 addresses concerns for people on the ground. With any aircraft, there is a risk that a loss of propulsion could result in the aircraft descending, controlled or otherwise, to the ground. In addition, with sUAS, there is a possibility that the control link between the aircraft and the operator may be interrupted for any number of reasons.

The proposed rule requires that, prior to undertaking a flight, the operator of an sUAS familiarize himself with conditions and potential risks.36 The operator must assess the operating environment, considering (a) risks to persons and property in the immediate vicinity both on the surface and in the air; (b) weather; (c) airspace restrictions; and Aviation - Regulatory (d) the location of persons and property and other ground hazards.37 The sUAS operator must conduct a safety briefing with all persons involved in the operation,38 and he must ensure that the links between the ground station (remote control) and the sUAS are operating,39 and ensure that the sUAS has sufficient power for the flight.40 In addition to preflight precautions, the proposed regulations seek to protect ground personnel by providing that no person may operate an sUAS over a human being who is not participating in its operation, unless he or she is located under a covered structure that can provide protection from a falling sUAS.41 This requirement for a sterile environment is significant limitation on the operation of small unmanned aircraft, but responds to what the FAA views as a significant risk associated with the loss of positive control. Operator Certification Prior to the release of the proposed rule, there was concern in the sUAS community that the FAA might require drone operators to hold a private pilot certificate. The concern arose out of experience with the Section 333 Exemption process in which the FAA required just that. While the proposed rule does not require a private pilot certificate, the proposed rule does require an sUAS operator to obtain an unmanned aircraft airman certificate with a small UAS rating. The unmanned aircraft airman certificate is a new FAA certificate created to meet the statutory requirement that aircraft be operated only by an “airman.” Like manned aircraft pilots, sUAS operators will be directly responsible for, and will be the final authority as to the operation of the aircraft.42 The operator is also responsible for ensuring that the sUAS will pose no undue hazard to other aircraft, people or property in the event of a loss of control of the aircraft for any reason.43 The proposed rule would require applicants for an unmanned aircraft operator certificate with an 8 . sUAS rating to be at least 17 years of age. An operator would also need to demonstrate English language proficiency and pass an initial aeronautical knowledge test, as well as a recurrent knowledge test every 24 months.44 The knowledge test will cover the applicable regulations, knowledge of airspace classification, operating requirements, obstacle clearance requirements, and flight restrictions affecting sUAS operation, weather, and a variety of other topics bearing on sUAS operation.45 Operators of sUAS will not be required to obtain an FAA medical certificate. Instead, they are permitted to “self-certify,” which would require one to abstain from operating an sUAS if the operator is aware of any physical condition that could interfere with the safe operation of the aircraft. Small UAS operators are also required to comply with the alcohol and drug use prohibitions contained in 14 C.F.R.

section 91.17. Airworthiness Certification The proposed rule, to the relief of the sUAS community, will not require airworthiness certification of sUAS. The FAA recognized that the certification requirements contained in Parts 23 and 25 were designed for manned aircraft. The process is complex, expensive and would take three to five years for an sUAV to obtain type certification. With some candor, the FAA recognized that the development of unmanned aircraft was taking place at such a pace that, by the time a design was certified, it would be obsolete.

The FAA considered this unnecessary and counterproductive. Similarly, the FAA elected not to require formal aircraft inspections similar to those imposed on manned aircraft. Instead, the proposed rule requires that, prior to every flight, the operator inspect the sUAS to ensure that it is in a condition for safe operation.

In addition, the operator would be required to terminate the flight when he knows or has reason to know that continuing the flight would pose a hazard to other aircraft, people or property.46 Aviation - Regulatory As with manned aircraft, the FAA has included in Part 107 a regulatory catch requiring that an sUAS not be operated in a careless or reckless manner so as to endanger the life or property of another.47 This section mirrors 14 C.F.R. section 91.13 applicable to manned aircraft, and pilots who have been the subject of FAA enforcement actions are aware that this catch-all provision accompanies nearly all FAA allegations of regulatory violation. Any failure to comply with the Part 107 regulatory scheme likely will be accompanied by a section 107.23(a) violation, which usually serves to increase the penalty.

A “careless and reckless” provision also fills any gaps that may exist in the regulations. The FAA’s proposed Part 107 is a tentative first step toward the integration of unmanned aircraft – small or otherwise – into the national airspace system. It may be a year or more before we see a final rule. It may be many more years before we see a rule that encompasses the use of large UAS.

The FAA has been feeling, and will continue to feel, ever-increasing pressure to keep regulatory pace with advances in UAS technology. The FAA, as currently constituted, is unable to do this, and it will be interesting to see how the Agency will be changed by the arrival and evolution of commercial drones. The Bottom Line The Pirker decision by the NTSB propelled commercial drones into the spotlight and under the regulatory watch of the FAA. Currently, entities seeking to operate sUAS for commercial reasons will require a case-by-case review and exemption pursuant to section 333. In the meantime, the FAA has proposed Part 107, a set of rules providing guidance and safety standards only for the operation of sUAS (aircraft below 55 pounds) that specifically addresses collision risk, ground personnel safety, operator certification and responsibilities, and aircraft requirements. 9 .

When Part 107 is adopted, commercial users will be able to operate sUAS pursuant to these regulations without a section 333 exemption. At present, the FAA will not permit the recreational or commercial operation of UAS above 55 pounds. While certain commercial operators (like Amazon) have received experimental airworthiness certificates for large UAS, they may only be used for experimental and testing purposes. Those wishing to operate sUAS for commercial purposes should apply for the section 333 exemption – in which operators will need to demonstrate to the FAA that they will either meet applicable regulations, or provide equivalent levels of safety – as well as consider related legal issues that may impact their activities. Aviation - Regulatory 10 .

-- CHAPTER 3 -Copyright (EU) Chapter Author Stephen Edwards, Partner - sedwards@reedsmith.com The use by film and television programme makers and by photographers of drone-mounted cameras has rapidly become commonplace. Aerial pictures that previously could only be obtained by using helicopters or light aircraft can now be shot at a fraction of earlier costs. The pictures taken, whether still or moving, can have high news value and high economic value too. As the costs of drone-technology reduce, the taking of aerial pictures of high personal value but little or no economic value comes within the reach of ordinary citizens. But is there copyright in such still or moving pictures and, if so, who owns it? In the case of still pictures, copyright will subsist if the photograph is the intellectual creation of the photographer. So if the photograph is taken when someone can see, through a remote viewfinder, what picture will be taken if they press the right button, there will almost certainly be a copyright in the photograph that results from a decision to take it.

Conversely, if the camera simply takes a random photograph of an area without any element of choice on the part of a person as to such elements as the focus and framing, it’s unlikely that the threshold requirement of intellectual creation will be met. As to who will be the first owner of the copyright, the UK rule is that it will be the photographer, unless the photograph was taken in the course of the photographer’s duties as an employee. In the latter case, the employer will be the first owner. The position is rather different if the camera takes moving pictures. These are defined in UK copyright law as "films". Copyright (EU) As to whether copyright in the film will subsist, a notable feature of UK copyright law is that the film does not have to pass the test of being the intellectual creation of the author.

Even a film taken randomly by a drone-mounted camera, without intervention by anyone who can see what pictures the camera is recording, will qualify as a copyright work. The question as to who is the first copyright owner of such a film is rather more difficult. Under UK copyright law, a film has two initial owners, the producer and the principal director. If either of them has made the film as employees under a contract of employment, then again their employer will own their share of the copyright. But the more difficult question is whether the film actually has a principal director. There’s no statutory definition of such a person, but case law indicates that it is the person who has creative control, in the sense of at least deciding what to film, how to film it, how to position the camera and what the shutter settings should be.

If no one involved in the use of the drone-mounted camera meets this requirement, copyright may yet subsist in the film. There will be no director’s copyright in it, but there will still be the producer’s copyright – the producer being the person who makes the arrangements necessary for its production. Finally, of course, anyone using a dronemounted camera to take a photograph or film needs to take care not to infringe the copyright in any work included in the photograph or film. UK copyright law includes a handy exception allowing incidental inclusion of a copyright work in a photograph or film, but this obviously will not apply if the photographer or film-maker is 11 .

focusing on the work in question in order to create an effect or make a point. A particular pitfall is another exception to copyright protection, which photographers and film makers frequently rely upon, but which may not protect them when using drone-mounted cameras. Under UK copyright law, it is not an Copyright (EU) infringement of the copyright in a sculpture or a work of artistic craftsmanship which is permanently situated in a public place to include it in a photograph or film. Drones can enable a viewer to see into private open spaces such as gardens; it could be a costly mistake to use one in order to film a famous but private sculpture collection. 12 . -- CHAPTER 4 -Employment and Labor Chapter Authors Cindy Schmitt Minniti, Partner - cminniti@reedsmith.com Mark Goldstein, Associate – mgoldstein@reedsmith.com Drones are poised to become valuable tools in the workplace for their potential to improve safety, minimize operational costs, and revolutionize site security and surveillance. Already, a number of employers have cut down on work-related injuries by utilizing drones equipped with robotic arms to execute a range of inherently dangerous tasks typically performed by humans. Drone technology has also proved ideal for conducting workplace inspections, as drones can survey large areas and quickly develop cost-saving data. For example, drones equipped with special sensory equipment, such as infrared sensors, are now being used to detect specific points of heat loss from office buildings to improve energy efficiency. Moreover, drones mounted with high-resolution, live-feed cameras may soon serve as effective workplace security systems, as well as effective employee monitoring tools.

Although the advantages to drones in the workplace are numerous, the technology may also force employers to review their policies on employee privacy, or risk a lawsuit. Indeed, the Federal Wiretapping Act/Electronic Communications Privacy Act prohibits the intentional interception or disclosure of any oral communication, without a person’s consent, where there is a reasonable expectation of privacy. Violating this statute can lead to criminal sanctions--including imprisonment--as well as civil fines. In addition to the Federal Wiretapping Act, many states have adopted comparable wiretapping statutes that may impact an employee monitoring program.

While federal law only requires one-party consent to a recorded oral conversation, twelve states require the consent of all recorded parties. Those jurisdictions are California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Washington. Federal & State Wiretapping Acts Hidden Cameras As drones with recording capacities grow smaller, employers should be aware of the laws governing workplace recordings. So far, the law has not significantly infringed upon a private employer’s right to monitor workplace computer communications, text messages, or web site visits when those activities take place on an employer-owned device.

The law does, however, place limits on an employer’s right to monitor an employee’s telephone or oral communications in the workplace. Employment and Labor In light of these laws, employers wishing to use drones to monitor employee conversations will be in a much better position to protect themselves from legal challenges if they obtain employee consent, before recording, as a condition of employment. Drones that record only video for security purposes are legal in public workspaces. Private spaces in the workplace, such as bathrooms, locker rooms, dressing rooms, etc., should not be recorded. A gray area, however, still exists as to whether an employee’s office is private or public under common law.

To avoid uncertainty, employers should, again, notify employees that all office premises, including private offices, may be under surveillance, and obtain consent. 13 . -- CHAPTER 5 -Export Controls Chapter Author Peter Teare, Partner – PTeare@reedsmith.com The potential military and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) applications of drones bring them squarely within the scope of international export control policy and regulation. The licensing requirements are not, however, limited to products intended for a military or ISR use. International sales of almost all commercial unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) systems and many of their sub-systems require a license authorization for export. Scope of the Licensing Obligation The licensing rules have broad application in the context of drones. Any UAV having an autonomous flight control and navigation capability – or that can be operated remotely outside of direct visual range of the operator, other than model aircraft – is likely to require a license for export.

The licensing requirements also extend to sub-systems and component parts, such as autopilots, positioning equipment, and flight control systems and their component parts. Export licensing controls also apply to crossborder transfers of technology required for the development, production or use of UAVs and UAV sub-systems. An email to a colleague in another country containing operating instructions may be a licensable export. The nature of the licensing obligations applicable to UAVs varies according to the intended application and capabilities of the system. The extended range and carrying capacity of certain products brings them within the same rules governing international sale of cruise missiles. The controls, which are designed to prevent sensitive products and technologies falling into Export Controls the hands of unfriendly states or terrorists groups, are taken seriously.

In most countries, the export controls are vigorously policed and enforced, and violations carry significant criminal penalties. The International Regulatory Framework Most countries, including the United States and each of the EU member states, have adopted a comprehensive export control regime to prevent the proliferation of sensitive products and technologies to countries, groups and individuals regarded as a potential threat to national security. These national rules respond to commitments under multilateral agreements and, in some cases, add additional unilateral compliance obligations. No country wants its defense and security technologies deployed against its own peoples, and most have sophisticated licensing and enforcement regimes to limit that risk. The lists of products and technologies subject to licensing controls are developed multilaterally under international agreements.

The two regimes relevant to both target drones and reconnaissance drones are the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies, which has 41 signatory states, and the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), which has 34 signatories. The Wassenaar Arrangement has established two lists of controlled products and technology: ï‚· A "Munitions List" of equipment and technology designed for military use 14 . ï‚· A "Dual-Use List" of products and technology that, regardless of the purpose for which they were developed, have both commercial and military applications underwater), aircraft and more recently, UAVs designed for military use. Category ML10.c of the Munitions Lists controls: ï‚· Unmanned airborne vehicles specially designed or modified for military use, including remotely piloted air vehicles (RPVs), autonomous programmable vehicles and "lighter-than-air vehicles" ï‚· Associated launchers ground support equipment ï‚· Related equipment for command and control The Missile Technology Control Regime has developed additional classes of controlled items designed to limit the proliferation of systems capable of delivering weapons of mass destruction. The countries participating in the Wassenaar Arrangement and MTCR have each agreed to adopt these common lists of products to be subjected to export controls, and to transpose them into national law under an effective export licensing regime. The licensing arrangements and enforcement regimes vary from country to country, but the scope of the controls are defined by these lists. Accordingly, the rules defining which UAVs and UAV systems are subject to export licensing controls are broadly similar throughout the world. In the United States, products and technology appearing on these lists are controlled variously under the U.S.

International Trade in Arms Regulations (ITAR) as items on the U.S. Munitions List (USML), or under the U.S. Export Administration Regulations (EAR) as items on the Commerce Control List (CCL). Similarly, within the European Union, the DualUse List has been adopted as EU law directly applicable in all 28 member states as the EU Dual-Use Regulation (Regulation No. 428/2009). Munition List items are regulated individually by the member states through the Common Military List of the European Union. The Munitions List The Munitions List has been expanded beyond munitions.

It includes a broad range of products other than weapons and ammunition, such as military vehicles, combat vessels (surface or Export Controls and Sub-systems and components themselves designed for military use may be separately controlled. For example, each of the following is individually controlled under the Munitions List: ML10.d Aero--â€engines specifically designed or modified for military use. ML15.b Cameras, components and accessories specially designed for military use. ML15.d Thermal and infrared imaging equipment, components and accessories specially designed for military use. Dual-Use List The Dual-Use List controls the following categories that specifically address non-military UAVs: 9.A.12.a UAVs and related equipment and components designed to have controlled flight out of the direct natural vision of the operator and having either (1) a maximum endurance greater than or equal to 30 minutes but less than 1 hour, and designed to take off and 15 . have stable controlled flight in wind gusts equal to or exceeding 46.3 km/h (25 knots), or (2) a maximum endurance of 1 hour or greater. 9.A.12.b.3 Equipment or components specially designed to convert a manned aircraft to a UAV specified by above. 9.A.12.b.3 Air breathing reciprocating or rotary internal combustion-type engines, specially designed or modified to propel UAVs at altitudes above 15,240 meters (50,000 feet). 9.B.10 Equipment specially designed for the production of items specified above. 9.D.1, 9.D.2 and 9.D.4.E Software specially designed or modified for the development, product or production of equipment or technology specified above. 9.E.1 and 9.E.2 Technology required for the development or production of equipment or software specified above. Model aircraft are expressly excluded from these control categories. Missile Technology Control Regime The focus of the MTCR is to limit the proliferation of missiles capable of delivering weapons of mass destruction. Its scope includes cruise missiles, target drones, reconnaissance drones, and other forms of UAVs, regardless of whether they are military or commercial, or armed or unarmed. Specifically, the MTCR definition of UAVs controls: 19.A.2 Complete unmanned aerial vehicle systems (including cruise missile systems, target drones and reconnaissance drones) having a range equal to or greater than 300 kilometers. Export Controls The MTCR requires participating governments to apply a “strong presumption of denial” to license applications for military and commercial UAV systems capable of a range of at least 300 kilometers and that are capable of carrying a payload of at least 500 kilograms, but also permits such exports on “rare occasions” that are well justified by reference to the non-proliferation and export control factors specified in the MTCR Guidelines. Technology Transfers The licensing controls on international sales of drones are not limited to exports of physical product. It includes transfers of technology required for the development, production or use of controlled items.

The definition of technology is broad as it includes blueprints, designs, technical data, manufacturing drawings and manuals. An export of controlled technology can take place electronically by means of a simple email or downloading data from a server, or hand-carrying a memory stick or laptop containing controlled data. Export Authorization A controlled product or technology requires a license or other export authorization granted by the relevant national licensing authority. While most countries adopt the same lists of controlled items, the manner in which licenses are issued varies from country-to-country. In the United States, licensing responsibility is shared between the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) within the U.S. Department of Commerce, and the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) within the U.S.

State Department. BIS implements the dual-use control system through the U.S. Export Administration Regulations (EAR), whereas DDTC has historically implemented controls on Munitions List items through the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR).

As a consequence of 16 . recent reforms to the U.S. export control regime, however, many UAV sub-systems and components containing low-risk technology previously controlled under the Munitions List have been moved to the Commerce Control List (CCL) and are now regulated by the less restrictive EAR. Within the European Union, dual-use controls are implemented through the EU Dual-Use Regulation that is directly applicable in all EU member states. Most dual-use items may circulate freely within the European Union and only require a license when going to a person or place outside the EU. Munitions List items continue to be regulated individually by the member states by national law, and require a license when going outside national borders. The European Union has adopted a system of General Export Authorisations (GEAs) to facilitate the export authorisation of international sales and transfer of low-risk technologies to friendly countries.

Use of the GEA requires only registration with the relevant national licensing authority and compliance with the license conditions, which are generally in the nature of record-keeping requirements and annual notifications. U.S. Licensing Policy on Military Drones A report by the Stimson Center’s Drone Task Force in June 2014 recommended that the U.S. government examine the broader nonproliferation effect of the MTCR presumption of denial for drones with a range of least 300 kilometers and that are capable of carrying a payload of at least 500 kilograms. The rule has severely restricted sales of armed drones by U.S. manufacturers despite the demand from nonU.S.

governments. The Stimson Center’s Drone Task Force said that the U.S. government should determine whether the presumption remains a useful non-proliferation tool or merely facilitates the growth of UAV manufacturing outside the United States. Export Controls In February 2015, the United States government announced a new policy for the licensing of commercial and military U.S.-origin UAVs and UAV systems.

It re-affirmed its commitment to the MTCR’s “strong presumption of denial” for export of UAVs with a range of at least 300 kilometers and that are capable of carrying a payload of at least 500 kilograms, but describes the “Principles for Proper Use” of U.S.-Origin Military UAVs under which the U.S. may nevertheless grant a license authorization. The new policy contemplates licensing sales to “trusted partner nations, increasing U.S. interoperability with these partners for coalition operations, ensuring responsible use of these systems, and easing the stress on U.S. force structure for these capabilities.” In opening the door to exports of armed UAV systems, the policy also introduces enhanced licensing controls for such products, including “potential requirements” for: ï‚· Sales and transfers of sensitive systems to be made through the government-togovernment Foreign Military Sales program, precluding direct exports by manufacturers to non-U.S.

government and commercial customers ï‚· A review of potential transfers to be made through the Department of Defense Technology Security and Foreign Disclosure processes ï‚· Each recipient nation to be required to agree to end-use assurances as a condition of sale or transfer ï‚· End-use monitoring and potential additional security conditions to be required ï‚· All sales and transfers to include agreement to principles for proper use 17 . Non-U.S. governments wishing to purchase U.S. manufactured armed drones will be required to commit to “proper use” principles and not use UAVs “to conduct unlawful surveillance or [for] unlawful force against their domestic populations.” U.S. Export Control Reform The recent reforms to the U.S. control regime aimed at making it easier for defense manufacturers to make international sales of lowrisk technologies to overseas government and commercial customers have eased controls on many UAV sub-systems and components previously controlled under the U.S.

Munitions List. As a consequence, ITAR registration is no longer required for manufacturers that produce sub-systems and components subject to only Commerce Department controls. One effect of these reforms may be to remove a serious competitiveness issue for U.S. manufacturers when selling to non-U.S. customers concerned that the use of a part or component subject to U.S. ITAR control will infect the built UAV system and bring it within the Export Controls jurisdiction of U.S.

regulation and licensing requirements on export. Where incorporated parts are subject to only Commerce Department controls, the United States will generally only assert licensing control if the built system incorporates more than 10 percent of U.S. content by value. Implications for Manufacturers and Suppliers Military and commercial UAVs and UAV systems are among the most closely controlled products for export. With the exception of model aircraft, the international sale of a drone is almost certainly going to require an export authorization. Manufacturers and suppliers that are not already in the business of exporting controlled equipment or technologies will be required to invest compliance policies and procedures.

Once established, however, the ongoing compliance costs are likely to be justified by the growing international demand for drone devices and technologies. 18 . -- CHAPTER 6 -Film and Television (UK) Chapter Authors Gregor Pryor, Partner - gpryor@reedsmith.com Nick Breen, Associate – nbreen@reedsmith.com The development of drones in recent years has created a wide range of exciting opportunities, particularly for filming and photography. A number of Hollywood productions have already taken advantage of the technology, including Skyfall, Van Helsing and, more recently, The November Man, as well as certain television programmes such as Top Gear and coverage of live cricket. However, the use of drones for filming requires studios, production companies and broadcasters to consider issues which they may never have considered before, including requirements of aviation law. Conversely, aviation authorities are having to quickly come to grips with the idiosyncrasies of media law, as the use of drones for entertainment purposes increases at an exponential rate. As is common in the media and technology industry, the technology is developing far quicker than the law is able to predict, which can often lead to uncertainty and a degree of risk. Use of drones in the UK for filming is nothing new, but is certainly gaining in popularity and sophistication.

While the UK requirements and regulations are less strict than those in the United States, it is still critical that those wishing to use drones be aware of and follow such requirements and regulations to avoid invalidating a production’s insurance policy, or risking the imposition of criminal sanctions. UK Regulation In the UK, the use of drones (also referred to as “unmanned aircrafts” or “UA”) is subject to Film and Television (UK) various rules and restrictions. The level and extent of the applicable restrictions will depend on a number of factors, but mainly the weight and proposed use of the drone. Weight. In a similar manner to other forms of aircraft, the relevant legislation applicable to the operation of drones is the Air Navigation Order 2009 (ANO) effected through the Civil Aviation Act 1982.

Under this measure, if a drone weighs more than 20kg, then it will be treated similarly to a manned aircraft and be subject to various onerous regulations and requirements. Among other things, such drones are subject to severe fly-zone restrictions, will need to pass airworthiness tests, and will need to be registered with the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). For the purposes of filming and photography, most drones will weigh significantly less than 20kg. If this is the case, the drone will be classed as a “small unmanned aircraft” under Article 253 of the ANO and will therefore, to a large extent, avoid the minefield of aviation regulation.

For the purposes of this chapter, we will look only at the rules and regulations applicable to drones weighing less than 20kg. Use. The provisions of the ANO most relevant to the use of drones for filming are Articles 166 and 167. While Article 166 applies to all drones weighing less than 20kg and is general in application, Article 167 only applies to “small unmanned surveillance aircrafts”, meaning drones equipped to undertake any form of surveillance or data acquisition – in other words, drones with a camera or other recording equipment. 19 .

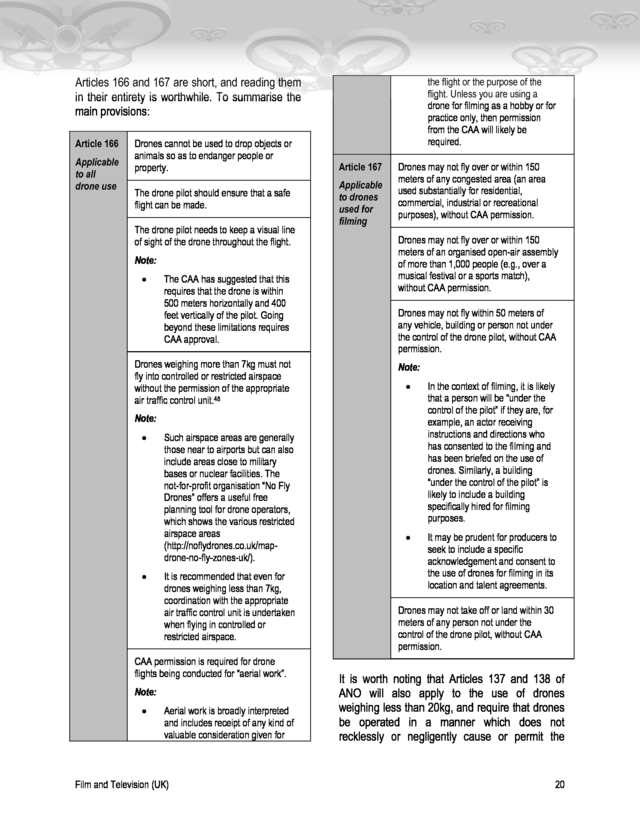

Articles 166 and 167 are short, and reading them in their entirety is worthwhile. To summarise the main provisions: Article 166 Applicable to all drone use Drones cannot be used to drop objects or animals so as to endanger people or property. The drone pilot should ensure that a safe flight can be made. The drone pilot needs to keep a visual line of sight of the drone throughout the flight. Note: ï‚· The CAA has suggested that this requires that the drone is within 500 meters horizontally and 400 feet vertically of the pilot. Going beyond these limitations requires CAA approval. Drones weighing more than 7kg must not fly into controlled or restricted airspace without the permission of the appropriate air traffic control unit.48 the flight or the purpose of the flight. Unless you are using a drone for filming as a hobby or for practice only, then permission from the CAA will likely be required. Article 167 Applicable to drones used for filming Drones may not fly over or within 150 meters of any congested area (an area used substantially for residential, commercial, industrial or recreational purposes), without CAA permission. Drones may not fly over or within 150 meters of an organised open-air assembly of more than 1,000 people (e.g., over a musical festival or a sports match), without CAA permission. Drones may not fly within 50 meters of any vehicle, building or person not under the control of the drone pilot, without CAA permission. Note: ï‚· In the context of filming, it is likely that a person will be “under the control of the pilot” if they are, for example, an actor receiving instructions and directions who has consented to the filming and has been briefed on the use of drones.

Similarly, a building “under the control of the pilot” is likely to include a building specifically hired for filming purposes. ï‚· It may be prudent for producers to seek to include a specific acknowledgement and consent to the use of drones for filming in its location and talent agreements. Note: ï‚· ï‚· Such airspace areas are generally those near to airports but can also include areas close to military bases or nuclear facilities. The not-for-profit organisation “No Fly Drones” offers a useful free planning tool for drone operators, which shows the various restricted airspace areas (http://noflydrones.co.uk/mapdrone-no-fly-zones-uk/). It is recommended that even for drones weighing less than 7kg, coordination with the appropriate air traffic control unit is undertaken when flying in controlled or restricted airspace. CAA permission is required for drone flights being conducted for “aerial work”. Note: ï‚· Aerial work is broadly interpreted and includes receipt of any kind of valuable consideration given for Film and Television (UK) Drones may not take off or land within 30 meters of any person not under the control of the drone pilot, without CAA permission. It is worth noting that Articles 137 and 138 of ANO will also apply to the use of drones weighing less than 20kg, and require that drones be operated in a manner which does not recklessly or negligently cause or permit the 20 . drone to endanger a person, property or other aircraft. required and, if granted, will need to be renewed every 12 months. Permission required from the CAA If permission is granted by the CAA, it may be subject to a number of additional restrictions or requirements. For instance, it is usually a requirement for the drone to be equipped with a mechanism that will cause the drone to land in the event of disruption of any of its control systems, and for the permission of the landowner on whose land the drone is intended to take off and land. The CAA may also prohibit flights which have not been notified to the local police prior to the flight taking place. Such restrictions make it critical for filmmakers and production companies to ensure that, in addition to obtaining CAA permission, they seek all relevant permissions from land owners, the council, park authorities and, where applicable, the police, in plenty of time before using a drone. From the above summary, it is clear that where you either intend to: (a) fly the drone on a commercial basis (which, for most filming, is likely to be the case); or (b) fly the drone within congested areas or close to people or properties that are not under your control, then you will need to request permission from the CAA before doing so.49 As of February 2015, the CAA has issued more than 480 permissions to drone operators, up from only 230 in February 2014.

These permissions have been given to film studios, production companies, and the BBC, as well as to organisations from other industries. Because of the complexity and bureaucracy involved in operating drones for filming in the UK, smaller production companies often seek specialist qualified contractors which have the necessary CAA permissions to undertake the filming work on their behalf. Where permission is required from the CAA, operators will be required to, among other things, demonstrate that they have considered the safety implications and taken necessary steps to ensure that the flight will not put anybody in danger. Additionally, the CAA may require operators to demonstrate a minimum level of competency of the drone pilot. Unlike the licensing procedure established for a manned aircraft, there is currently no official standard against which “competence” can be tested, although the CAA has approved several training organisations from which pilots can obtain the required skills. To apply for permission, applicants must complete and submit Form SRG1320 available from the CAA website and pay the applicable charge.50 Applications should be made at least 30 working days before the permission is Film and Television (UK) The CAA guidance note CAP 722 entitled “Unmanned Aircraft System Operations in UK Airspace – Guidance”51 is a helpful resource which outlines the main rules, regulations and guidance applicable to using unmanned aircraft. While a large proportion of the guidance is not applicable to drones weighing less than 20kg, it nevertheless considers the points we have discussed in this section in greater detail.

In particular, the guidance clarifies that it is the “operator” (being the person having management of the drone, rather than someone contracting the operator) who should apply for the relevant permission. This is important for production companies that may wish to appoint one particular operator who has been granted the relevant permissions and who is competent to fly the drone. Penalties The penalties for breach of drone regulations are not inconsiderable. The CAA has issued a warning that those caught in breach could face fines of up to £5,000.

Although prosecutions in the UK are currently few in number, they are 21 . steadily increasing. The first such prosecution resulted in a fine of £3,500 when an operator lost control of his drone, which then flew too close to a road bridge and a nuclear submarine facility. Other operators have been prosecuted for flying drones over Alton Towers and over football matches. Although this chapter has focussed on application in the United Kingdom, other countries within Europe are facing these issues and have similar rules and regulations in place restricting the use of drones. For instance, Germany, France and Spain all approach the regulation of drones based on their weight, purpose and intended use (i.e., whether for commercial work or not). While the rules may be similar, it is critical for operators to understand the specific local requirements in each target jurisdiction, particularly when the penalties for misuse of drones can vary dramatically between territories. The Bottom Line Top Tips for Drone Use ï‚· Be aware of your surroundings – research your flight zone before commencing work.

If the flight zone is within restricted airspace then you will need to liaise with the appropriate Air Traffic Control unit. ï‚· Be mindful of the weather – it could disrupt your drone and cause it to go outside your control/line of sight. ï‚· Be sure to get permission of the land owner whose property you are using to take off and land. If the land is not privately owned then this may require seeking permission from the local council. ï‚· Respect people’s privacy and rights. Seek permission before filming people where they may be identifiable. See the Privacy chapters for more information. ï‚· Ensure that only qualified and capable pilots operate the drone itself.

If CAA permission is required, the drone operator will need to be disclosed to the CAA in advance. ï‚· When in doubt, seek permission from the CAA and allow plenty of time to do so. Film and Television (UK) 22 . -- CHAPTER 7 -Film and Television (U.S.) Chapter Authors Michael Sherman, Partner – msherman@reedsmith.com Michael Hartman, Associate – mhartman@reedsmith.com Ross Kelley, Associate – rkelley@reedsmith.com Introduction This chapter looks at the relationship between drones and the film and television industry. The demand for drones in the entertainment realm is real. Whether it’s a scene of an awardwinning rooftop motorcycle chase,52 an aerial shot of a modest tree line,53 or a simple video of a wedding ceremony,54 production companies, news reporters, and amateur videographers have been clamoring for drones for years. With such high demand and (until very recently) no real viable domestic option for production firms, videographers were forced to use drones in other countries55 or shoot illegally.56 Landmark FAA Exemptions for Production Companies However, after a recent decision by the FAA, the ultimatum between shooting abroad or shooting illegally at home can now be a decision of the past. On September 25, 2014, the FAA granted regulatory exemptions to six aerial photo and video production companies.57 The Motion Picture Association of America facilitated the exemption requests on behalf of its six members: Astraeus Aerial, Aerial MOB, LLC, HeliVideo Productions, LLC, Pictorvision Inc., RC Pro Productions Consulting, LLC, and Snaproll Media, LLC.58 Film and Television (U.S.) This approval by the FAA was the first exemption to its ban on commercial drone use. Clearly, giving the first exemption of its kind to film production companies is a very good signal for other film and entertainment companies that want to use drones for their own commercial use. Bringing aerial drone production back to the United States presents a big opportunity for those companies that are quick enough to gain FAA exemption. Restrictions Imposed on the Use of Drones for Film The FAA explained that a key factor in the approval of the six aerial photo companies was their strong exemption applications, which included unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) flight manuals with detailed safety procedures. The application submission of these companies can serve as a role model for other film and television companies. Specifically, in their applications, the firms said the operators will hold private pilot certificates, keep the UAS within line of sight at all times, and restrict flights to the "sterile area" on the set. Additionally, in granting the exemption, the FAA added several other safety conditions, including an inspection of the aircraft before each flight, prohibiting operations at night, mandated flight rules, and timely reports of any accidents.59 These exemptions anticipated the framework of the landmark regulations proposed by the FAA 23 .

February 15, 2015, that would allow routine use of certain UAS. The proposed regulations include both operational limitations, such as the UAS can be no more than 55 pounds, fly no higher than 500 feet and no faster that 100 mph; and operator requirements, including that operators must be at least 17 years old, pass an aeronautical knowledge test, hold an FAA UAS operator certificate, and pass a TSA background check. Once passed, operators of commercial UAS will no longer require an exemption, and the use of UAS in Film and Television will likely expand. Benefits of Using Drones for Film, TV and Commercials The benefits of using drones for the film industry are far-reaching. UAS can take images at angles never before captured or navigate indoor areas that are otherwise difficult or impossible to reach. Besides covering new angles and environments, drones can also cover new heights; drones can reach altitudes higher than cranes and are much less expensive and more agile than a manned helicopter.60 Newsgathering Function Besides benefitting theatrical videographers, the use of drones has been shown to be quite valuable for newsgathering and reporting.

On January 12, 2015, CNN entered into a deal with the FAA to test the use of drones for newsgathering and reporting purposes. The deal involves a partnership between CNN and Georgia Tech Research Institute, with the purpose of such partnership to explore safety and access issues, and opportunities that need to be addressed as part of the impending new regulatory framework. Noting the significant opportunities unmanned aircraft offer news organizations, FAA Administrator Michael Huerta explained, “We hope this agreement with CNN and the work we are doing with other news organizations and associations will help safely integrate unmanned newsgathering technology Film and Television (U.S.) and operating procedures into the National Airspace System.”61 Days after CNN’s arrangement with the FAA was approved, a group of 10 media outlets, including the Associated Press, NBCUniversal and The New York Times, announced a similar arrangement.

The media outlets will be teaming with Virginia Tech to experiment using small drones in reporting and newsgathering in “real life scenarios.”62 The executive director of the Virginia Tech test site puts the advantage of newsgathering drones into perspective, stating, “UAS can provide this industry a safe, efficient, timely and affordable way to gather and disseminate information and keep journalists out of harm's way.” With drones providing a faster, cheaper, and safer alternative to many current forms of reporting, it will undoubtedly become a very popular means of newsgathering once the FAA and these early media outlets can establish proper safety guidelines. Privacy Concerns for Celebrities With arrangements to test newsgathering drones already in place and the approval for this use looming near, several organizations have voiced concerns about privacy issues. Particularly outspoken among these groups have been celebrities, who worry about “paparazzi drones.” State legislatures have begun to address and respond to these concerns. Chief among them is California, which has approved a law that will prevent paparazzi from using drones to take photos of celebrities.63 Concurrently with the release of the new FAA regulations, the White House released a memorandum regarding the privacy, civil rights and civil liberties in the domestic use of UAS, which requires the Department of Commerce – in consultation with other interested agencies – to initiate a multi-stakeholder engagement process to develop a framework for privacy, 24 .