Description

Sales Tax on Digital Equivalents:

Look Through to the True Object

by Brian J. Kirkell and Brad Hershberger

delivered via tangible property and equivalent goods

and services delivered electronically, only a difference in the means of delivery.

There is no functional difference

between goods and services

delivered via tangible property and

equivalent goods and services

delivered electronically.

Brian J. Kirkell

Brad Hershberger

Writing for the Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, Michael Mazerov argued for uniformity in

the sales tax treatment of goods and services delivered via tangible property and equivalent goods and

services delivered electronically, saying, ‘‘People

buying digital goods and services are consuming

economic resources just as people buying physical

goods are, so fairness dictates that they should pay

the same amount of [sales] tax on each dollar of such

spending.’’1 Although there is something attractive

in that sentiment, Mazerov ultimately missed the

mark in terms of both fairness and uniformity in

concluding that the appropriate resolution for the

disparity in treatment between goods and services

delivered via tangible and electronic means is for

states to adopt the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax

Agreement.2 The problem with that recommendation is that SSUTA’s treatment of digital goods and

services merely muddies the waters by continuing

the untenable distinction between goods and services delivered via tangible and electronic means

instead of striking at the core of the matter: There is

no functional difference between goods and services

1

Michael Mazerov, ‘‘States Should Embrace 21st Century

Economy by Extending Sales Taxes to Digital Goods and

Services’’ (Dec. 13, 2012).

2

See SSUTA sections 332 and 333.

Accordingly, states should recognize that from the

perspective of a consumer, the true object of the

transaction in purchasing goods and services via

digital download or through the cloud is functionally

equivalent to the purchase of the same goods and

services via a transfer of tangible property.

States should then look past the means of delivery to the true object of the transaction and define that object as tangible property subject to sales tax to the same extent, in the same manner, and susceptible to the same exemptions regardless of the media through which they are obtained. For example, regardless of whether a consumer purchases music on CD, by digital download, or through subscription to an online streaming music service, the consumer’s ultimate goal is to listen to music; that music is the product that should be taxed. SSUTA Treatment of Digital Goods and Services The SSUTA as amended on May 24, 2012, provides that a Streamlined Sales Tax Project member state3 may not subject ‘‘specified digital 3 As of the publication of this article, there are 22 SSTP full member states. They are Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Also, Ohio and Tennessee are in substantial compliance with the SSUTA and are SSTP associate members. For a current list of SSTP full (Footnote continued on next page.) State Tax Notes, April 29, 2013 365 (C) Tax Analysts 2013. All rights reserved.

Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. SALT matters . SALT Matters and associate member states, see http://www.streamline dsalestax.org/index.php?page=state-info. 4 In accordance with SSUTA Library of Definitions, Appendix C, Part II, Product Definitions, the term ‘‘specified digital products’’ is defined as electronically transferred digital audio-visual works, digital audio works, and digital books. The term ‘‘digital audio-visual works’’ means a series of related images transferred via electronic means that when shown in succession, impart an impression of motion, together with accompanying sounds, if any. The term ‘‘digital audio works’’ means works that are delivered via electronic means that result from the fixation of a series of musical, spoken, or other sounds, including ringtones. The term ‘‘digital books’’ means works that are delivered via electronic means that are generally recognized in the ordinary and usual sense of the term ‘‘books.’’ 5 In accordance with SSUTA section 332(I), a product is ‘‘transferred electronically’’ when it is obtained by the purchaser by any means other than the transfer of tangible property. 6 SSUTA sections 332(A) and 333. 7 SSUTA section 332. 8 SSUTA section 332(D)(1). 9 SSUTA section 332(D)(2) and (3), and 332(F). Note that in accordance with SSUTA section 332(G), transfers of digital code must be subject to the same tax treatment as the electronically transferred product to which the digital code relates. 10 SSUTA section 332(H). 366 Taken as a whole, the SSUTA provisions for the taxation of digital goods and services can be summarized as follows: an SSTP member state can tax the sale of any digital product in any manner it sees fit, subject to some definitional presumptions that can be overridden and limited by (1) a proscription against defining digital products as tangible property, and (2) a requirement that if a state provides a product-based exemption for specific digital goods and services, it must likewise provide a productbased exemption for functionally equivalent tangible property.

There is no prohibition of tax pyramiding,11 and no requirement for member states to tax digital goods and services in an externally consistent manner.12 Furthermore, although internal consistency between transfers of tangible property and digital equivalents is required when providing an exemption for a specified digital product, each state is free to favor transfers of tangible property with product-based exemptions that do not apply to 11 SSTP member states are welcome to, and largely do, tax business inputs. Businesses that sell commodities that cannot be subjected to price variations wind up ‘‘eating’’ the tax paid, reducing profitability. However, businesses generally do not ‘‘eat’’ the tax but instead pass it through to consumers through the sales price charged for their products, which is, in turn, subject to tax.

Multiple layers of taxable transfers create a situation in which sales tax is effectively imposed on sales tax paid. One common exception to this problem comes in the form of exemptions provided for purchases of tangible property used in the manufacturing of tangible property. However, because member states with those types of exemptions are prohibited from defining digital goods and services as tangible property, those exemptions provide no relief from tax pyramiding for sales of digital equivalents. 12 By permitting external inconsistency, the SSUTA may as well have required it. For example, Arkansas exempts sales of digital books, movies, games, and the like, but subjects sales of streaming audio and video services to tax (see A.C.A. section 26-52-301(3) and 2012 Arkansas SST Taxability Matrix, pp.

6-7, available at http://www.streamlinedsalestax.org/ uploads/downloads/State%20Compliance/Arkansas/2012/Ark ansas%20Taxability%20Matrix%202012%20Revised%208_23 _12.pdf), while another SSTP member state, Kentucky, taxes substantially all digital goods and services (see KRS sections 139.200(1)(b) and 139.310(2)). The other SSTP member states run the gamut between these two. Furthermore, taxability is not the only matter subject to wide variation in interpretation.

For example, North Carolina and several other member states subject digital goods and services to sales tax even if the purchaser is required to make continuous payments to use the good or service (see NC G.S. 105-164.4(a)(6b)), while other member states, such as Indiana, would exempt purchases of digital goods and services that require continuous payments (see IC section 6-2.5-4-16.4). Accordingly, even among the SSTP member states, wide variations in the taxation of digital goods and services require a taxpayer to research each state’s statutory scheme to make taxability determinations, and reliance on multistate taxability charts created under the SSUTA is misleading at best. State Tax Notes, April 29, 2013 (C) Tax Analysts 2013.

All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. products,’’4 or any other product transferred electronically,5 to tax by including those products within its definition of the terms ‘‘computer software,’’ ‘‘telecommunication services,’’ ‘‘ancillary telecommunications services,’’ or ‘‘tangible personal property.’’6 Instead, to tax those products, a member state must enact statutory language subjecting the transfer of one or more specifically enumerated electronically transferred products, or all such products, to sales tax as some form of heretofore unheard of taxable property or service.7 A member state that chooses to tax the transfer of one or more electronically transferred products has the discretion to determine whether the imposition of tax will be limited to circumstances in which the product is transferred to an end user or the tax will be imposed on intermediate transfers.8 Furthermore, a member state may decide whether to impose tax only on a transfer of a permanent right to use a product without additional consideration or to tax the transfer of any use right, such as a use right for a limited period of time or one that is contingent on the continued payment of a subscription or maintenance fee; the state may subject the same product to tax in a different manner depending on the conditions under which the product is transferred.9 Finally, a state that taxes electronically transferred products but provides a product-based exemption for a ‘‘specified digital product’’ must provide a product-based exemption for a functionally equivalent product that is not transferred electronically.10 . SALT Matters Business 1 Equipment and Supplies Purchased Business 2 $300,000 $300,000 Sales Tax Paid 0 15,000 Total Equipment and Supplies Cost 300,000 315,000 Other Costs 600,000 600,000 Total Costs 900,000 915,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 Newspaper Sales Inclusive of Sales Tax Sales Tax Remitted Net Income 0 47,619 100,000 37,381 Source: tables by authors digital equivalents. Finally, states may grace transfers of tangible property with entity-based and usebased exemptions that by default cannot apply to transfers of digital equivalents simply because digital goods and services cannot be defined as tangible property.13 Put simply, if the devil is in the details, the SSUTA provisions for the taxation of digital goods and services smell distinctly of brimstone when it comes to uniformity and fairness, and they fail ‘‘to simplify and modernize sales and use tax administration in the member states in order to substantially reduce the burden of tax compliance.’’14 If the devil is in the details, the SSUTA provisions for the taxation of digital goods and services smell distinctly of brimstone when it comes to uniformity and fairness. Many of the problems inherent in the SSUTA approach to digital goods and services can be best seen through the following example. State X is an SSTP member state that imposes a 5 percent sales tax on the sale of all electronically transferred products, regardless of the nature of the use right transferred and payment terms. State X provides no exemptions for electronically transferred products. State X likewise taxes all sales of tangible property at a 5 percent rate, subject to enumerated exemptions.

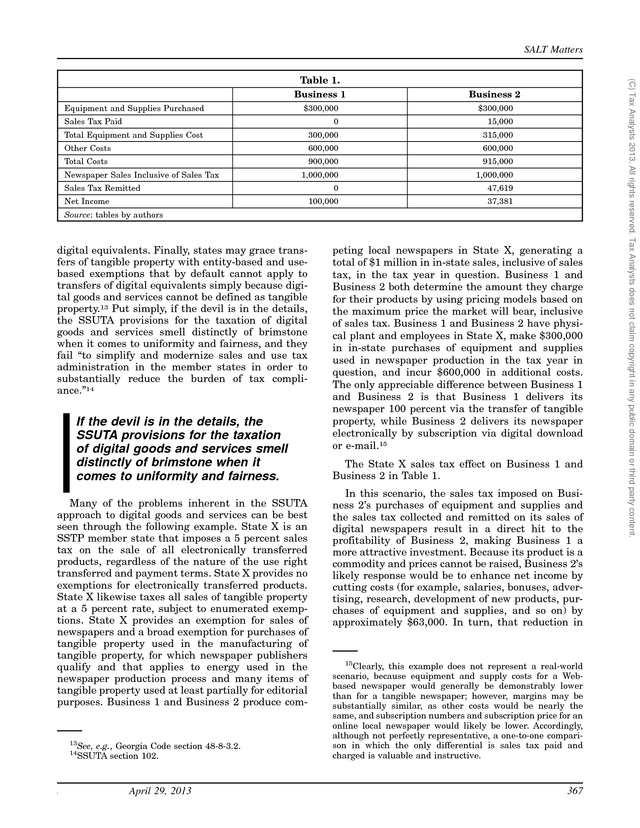

State X provides an exemption for sales of newspapers and a broad exemption for purchases of tangible property used in the manufacturing of tangible property, for which newspaper publishers qualify and that applies to energy used in the newspaper production process and many items of tangible property used at least partially for editorial purposes. Business 1 and Business 2 produce com- 13 See, e.g., Georgia Code section 48-8-3.2. SSUTA section 102. 14 State Tax Notes, April 29, 2013 peting local newspapers in State X, generating a total of $1 million in in-state sales, inclusive of sales tax, in the tax year in question. Business 1 and Business 2 both determine the amount they charge for their products by using pricing models based on the maximum price the market will bear, inclusive of sales tax.

Business 1 and Business 2 have physical plant and employees in State X, make $300,000 in in-state purchases of equipment and supplies used in newspaper production in the tax year in question, and incur $600,000 in additional costs. The only appreciable difference between Business 1 and Business 2 is that Business 1 delivers its newspaper 100 percent via the transfer of tangible property, while Business 2 delivers its newspaper electronically by subscription via digital download or e-mail.15 The State X sales tax effect on Business 1 and Business 2 in Table 1. In this scenario, the sales tax imposed on Business 2’s purchases of equipment and supplies and the sales tax collected and remitted on its sales of digital newspapers result in a direct hit to the profitability of Business 2, making Business 1 a more attractive investment. Because its product is a commodity and prices cannot be raised, Business 2’s likely response would be to enhance net income by cutting costs (for example, salaries, bonuses, advertising, research, development of new products, purchases of equipment and supplies, and so on) by approximately $63,000. In turn, that reduction in 15 Clearly, this example does not represent a real-world scenario, because equipment and supply costs for a Webbased newspaper would generally be demonstrably lower than for a tangible newspaper; however, margins may be substantially similar, as other costs would be nearly the same, and subscription numbers and subscription price for an online local newspaper would likely be lower.

Accordingly, although not perfectly representative, a one-to-one comparison in which the only differential is sales tax paid and charged is valuable and instructive. 367 (C) Tax Analysts 2013. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. Table 1. .

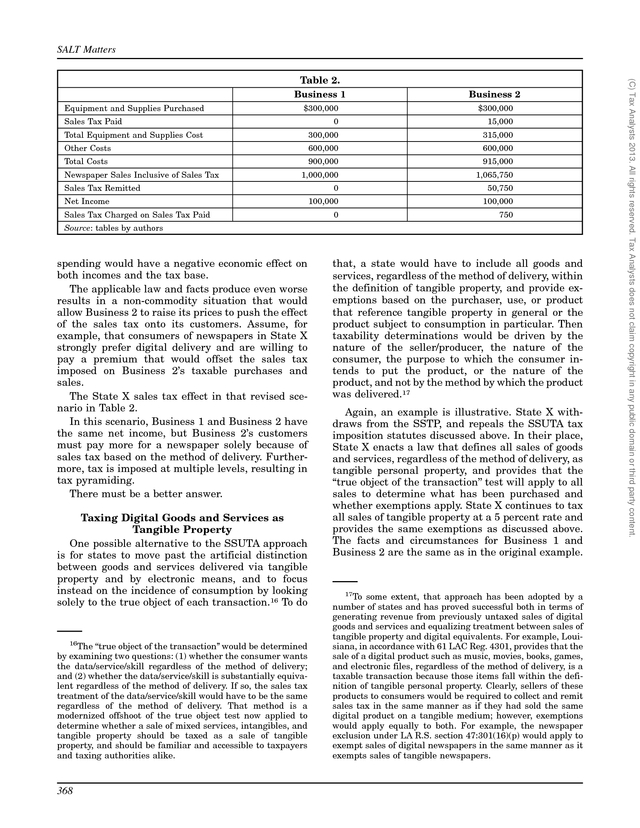

SALT Matters Business 1 Equipment and Supplies Purchased Business 2 $300,000 $300,000 Sales Tax Paid 0 15,000 Total Equipment and Supplies Cost 300,000 315,000 Other Costs 600,000 600,000 Total Costs 900,000 915,000 1,000,000 1,065,750 Newspaper Sales Inclusive of Sales Tax Sales Tax Remitted Net Income Sales Tax Charged on Sales Tax Paid 0 50,750 100,000 100,000 0 750 Source: tables by authors spending would have a negative economic effect on both incomes and the tax base. The applicable law and facts produce even worse results in a non-commodity situation that would allow Business 2 to raise its prices to push the effect of the sales tax onto its customers. Assume, for example, that consumers of newspapers in State X strongly prefer digital delivery and are willing to pay a premium that would offset the sales tax imposed on Business 2’s taxable purchases and sales. The State X sales tax effect in that revised scenario in Table 2. In this scenario, Business 1 and Business 2 have the same net income, but Business 2’s customers must pay more for a newspaper solely because of sales tax based on the method of delivery. Furthermore, tax is imposed at multiple levels, resulting in tax pyramiding. There must be a better answer. Taxing Digital Goods and Services as Tangible Property One possible alternative to the SSUTA approach is for states to move past the artificial distinction between goods and services delivered via tangible property and by electronic means, and to focus instead on the incidence of consumption by looking solely to the true object of each transaction.16 To do 16 The ‘‘true object of the transaction’’ would be determined by examining two questions: (1) whether the consumer wants the data/service/skill regardless of the method of delivery; and (2) whether the data/service/skill is substantially equivalent regardless of the method of delivery. If so, the sales tax treatment of the data/service/skill would have to be the same regardless of the method of delivery.

That method is a modernized offshoot of the true object test now applied to determine whether a sale of mixed services, intangibles, and tangible property should be taxed as a sale of tangible property, and should be familiar and accessible to taxpayers and taxing authorities alike. 368 that, a state would have to include all goods and services, regardless of the method of delivery, within the definition of tangible property, and provide exemptions based on the purchaser, use, or product that reference tangible property in general or the product subject to consumption in particular. Then taxability determinations would be driven by the nature of the seller/producer, the nature of the consumer, the purpose to which the consumer intends to put the product, or the nature of the product, and not by the method by which the product was delivered.17 Again, an example is illustrative. State X withdraws from the SSTP, and repeals the SSUTA tax imposition statutes discussed above.

In their place, State X enacts a law that defines all sales of goods and services, regardless of the method of delivery, as tangible personal property, and provides that the ‘‘true object of the transaction’’ test will apply to all sales to determine what has been purchased and whether exemptions apply. State X continues to tax all sales of tangible property at a 5 percent rate and provides the same exemptions as discussed above. The facts and circumstances for Business 1 and Business 2 are the same as in the original example. 17 To some extent, that approach has been adopted by a number of states and has proved successful both in terms of generating revenue from previously untaxed sales of digital goods and services and equalizing treatment between sales of tangible property and digital equivalents. For example, Louisiana, in accordance with 61 LAC Reg.

4301, provides that the sale of a digital product such as music, movies, books, games, and electronic files, regardless of the method of delivery, is a taxable transaction because those items fall within the definition of tangible personal property. Clearly, sellers of these products to consumers would be required to collect and remit sales tax in the same manner as if they had sold the same digital product on a tangible medium; however, exemptions would apply equally to both. For example, the newspaper exclusion under LA R.S.

section 47:301(16)(p) would apply to exempt sales of digital newspapers in the same manner as it exempts sales of tangible newspapers. State Tax Notes, April 29, 2013 (C) Tax Analysts 2013. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. Table 2. .

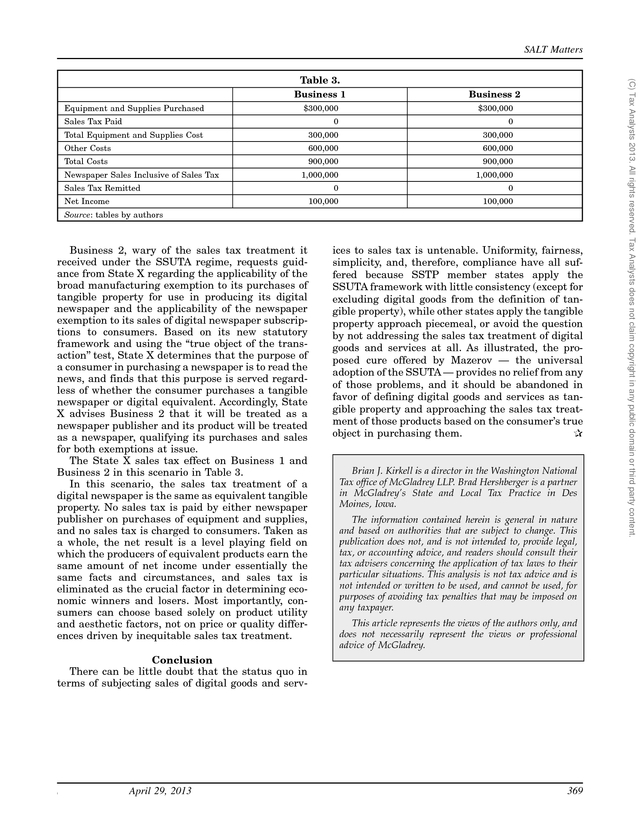

SALT Matters Business 1 Equipment and Supplies Purchased Business 2 $300,000 $300,000 Sales Tax Paid 0 0 Total Equipment and Supplies Cost 300,000 300,000 Other Costs 600,000 600,000 Total Costs 900,000 900,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 Newspaper Sales Inclusive of Sales Tax Sales Tax Remitted Net Income 0 0 100,000 100,000 Source: tables by authors Business 2, wary of the sales tax treatment it received under the SSUTA regime, requests guidance from State X regarding the applicability of the broad manufacturing exemption to its purchases of tangible property for use in producing its digital newspaper and the applicability of the newspaper exemption to its sales of digital newspaper subscriptions to consumers. Based on its new statutory framework and using the ‘‘true object of the transaction’’ test, State X determines that the purpose of a consumer in purchasing a newspaper is to read the news, and finds that this purpose is served regardless of whether the consumer purchases a tangible newspaper or digital equivalent. Accordingly, State X advises Business 2 that it will be treated as a newspaper publisher and its product will be treated as a newspaper, qualifying its purchases and sales for both exemptions at issue. The State X sales tax effect on Business 1 and Business 2 in this scenario in Table 3. In this scenario, the sales tax treatment of a digital newspaper is the same as equivalent tangible property. No sales tax is paid by either newspaper publisher on purchases of equipment and supplies, and no sales tax is charged to consumers.

Taken as a whole, the net result is a level playing field on which the producers of equivalent products earn the same amount of net income under essentially the same facts and circumstances, and sales tax is eliminated as the crucial factor in determining economic winners and losers. Most importantly, consumers can choose based solely on product utility and aesthetic factors, not on price or quality differences driven by inequitable sales tax treatment. ices to sales tax is untenable. Uniformity, fairness, simplicity, and, therefore, compliance have all suffered because SSTP member states apply the SSUTA framework with little consistency (except for excluding digital goods from the definition of tangible property), while other states apply the tangible property approach piecemeal, or avoid the question by not addressing the sales tax treatment of digital goods and services at all.

As illustrated, the proposed cure offered by Mazerov — the universal adoption of the SSUTA — provides no relief from any of those problems, and it should be abandoned in favor of defining digital goods and services as tangible property and approaching the sales tax treatment of those products based on the consumer’s true object in purchasing them. ✰ Brian J. Kirkell is a director in the Washington National Tax office of McGladrey LLP. Brad Hershberger is a partner in McGladrey’s State and Local Tax Practice in Des Moines, Iowa. The information contained herein is general in nature and based on authorities that are subject to change.

This publication does not, and is not intended to, provide legal, tax, or accounting advice, and readers should consult their tax advisers concerning the application of tax laws to their particular situations. This analysis is not tax advice and is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for purposes of avoiding tax penalties that may be imposed on any taxpayer. This article represents the views of the authors only, and does not necessarily represent the views or professional advice of McGladrey. Conclusion There can be little doubt that the status quo in terms of subjecting sales of digital goods and serv- State Tax Notes, April 29, 2013 369 (C) Tax Analysts 2013. All rights reserved.

Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. Table 3. .

States should then look past the means of delivery to the true object of the transaction and define that object as tangible property subject to sales tax to the same extent, in the same manner, and susceptible to the same exemptions regardless of the media through which they are obtained. For example, regardless of whether a consumer purchases music on CD, by digital download, or through subscription to an online streaming music service, the consumer’s ultimate goal is to listen to music; that music is the product that should be taxed. SSUTA Treatment of Digital Goods and Services The SSUTA as amended on May 24, 2012, provides that a Streamlined Sales Tax Project member state3 may not subject ‘‘specified digital 3 As of the publication of this article, there are 22 SSTP full member states. They are Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Also, Ohio and Tennessee are in substantial compliance with the SSUTA and are SSTP associate members. For a current list of SSTP full (Footnote continued on next page.) State Tax Notes, April 29, 2013 365 (C) Tax Analysts 2013. All rights reserved.

Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. SALT matters . SALT Matters and associate member states, see http://www.streamline dsalestax.org/index.php?page=state-info. 4 In accordance with SSUTA Library of Definitions, Appendix C, Part II, Product Definitions, the term ‘‘specified digital products’’ is defined as electronically transferred digital audio-visual works, digital audio works, and digital books. The term ‘‘digital audio-visual works’’ means a series of related images transferred via electronic means that when shown in succession, impart an impression of motion, together with accompanying sounds, if any. The term ‘‘digital audio works’’ means works that are delivered via electronic means that result from the fixation of a series of musical, spoken, or other sounds, including ringtones. The term ‘‘digital books’’ means works that are delivered via electronic means that are generally recognized in the ordinary and usual sense of the term ‘‘books.’’ 5 In accordance with SSUTA section 332(I), a product is ‘‘transferred electronically’’ when it is obtained by the purchaser by any means other than the transfer of tangible property. 6 SSUTA sections 332(A) and 333. 7 SSUTA section 332. 8 SSUTA section 332(D)(1). 9 SSUTA section 332(D)(2) and (3), and 332(F). Note that in accordance with SSUTA section 332(G), transfers of digital code must be subject to the same tax treatment as the electronically transferred product to which the digital code relates. 10 SSUTA section 332(H). 366 Taken as a whole, the SSUTA provisions for the taxation of digital goods and services can be summarized as follows: an SSTP member state can tax the sale of any digital product in any manner it sees fit, subject to some definitional presumptions that can be overridden and limited by (1) a proscription against defining digital products as tangible property, and (2) a requirement that if a state provides a product-based exemption for specific digital goods and services, it must likewise provide a productbased exemption for functionally equivalent tangible property.

There is no prohibition of tax pyramiding,11 and no requirement for member states to tax digital goods and services in an externally consistent manner.12 Furthermore, although internal consistency between transfers of tangible property and digital equivalents is required when providing an exemption for a specified digital product, each state is free to favor transfers of tangible property with product-based exemptions that do not apply to 11 SSTP member states are welcome to, and largely do, tax business inputs. Businesses that sell commodities that cannot be subjected to price variations wind up ‘‘eating’’ the tax paid, reducing profitability. However, businesses generally do not ‘‘eat’’ the tax but instead pass it through to consumers through the sales price charged for their products, which is, in turn, subject to tax.

Multiple layers of taxable transfers create a situation in which sales tax is effectively imposed on sales tax paid. One common exception to this problem comes in the form of exemptions provided for purchases of tangible property used in the manufacturing of tangible property. However, because member states with those types of exemptions are prohibited from defining digital goods and services as tangible property, those exemptions provide no relief from tax pyramiding for sales of digital equivalents. 12 By permitting external inconsistency, the SSUTA may as well have required it. For example, Arkansas exempts sales of digital books, movies, games, and the like, but subjects sales of streaming audio and video services to tax (see A.C.A. section 26-52-301(3) and 2012 Arkansas SST Taxability Matrix, pp.

6-7, available at http://www.streamlinedsalestax.org/ uploads/downloads/State%20Compliance/Arkansas/2012/Ark ansas%20Taxability%20Matrix%202012%20Revised%208_23 _12.pdf), while another SSTP member state, Kentucky, taxes substantially all digital goods and services (see KRS sections 139.200(1)(b) and 139.310(2)). The other SSTP member states run the gamut between these two. Furthermore, taxability is not the only matter subject to wide variation in interpretation.

For example, North Carolina and several other member states subject digital goods and services to sales tax even if the purchaser is required to make continuous payments to use the good or service (see NC G.S. 105-164.4(a)(6b)), while other member states, such as Indiana, would exempt purchases of digital goods and services that require continuous payments (see IC section 6-2.5-4-16.4). Accordingly, even among the SSTP member states, wide variations in the taxation of digital goods and services require a taxpayer to research each state’s statutory scheme to make taxability determinations, and reliance on multistate taxability charts created under the SSUTA is misleading at best. State Tax Notes, April 29, 2013 (C) Tax Analysts 2013.

All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. products,’’4 or any other product transferred electronically,5 to tax by including those products within its definition of the terms ‘‘computer software,’’ ‘‘telecommunication services,’’ ‘‘ancillary telecommunications services,’’ or ‘‘tangible personal property.’’6 Instead, to tax those products, a member state must enact statutory language subjecting the transfer of one or more specifically enumerated electronically transferred products, or all such products, to sales tax as some form of heretofore unheard of taxable property or service.7 A member state that chooses to tax the transfer of one or more electronically transferred products has the discretion to determine whether the imposition of tax will be limited to circumstances in which the product is transferred to an end user or the tax will be imposed on intermediate transfers.8 Furthermore, a member state may decide whether to impose tax only on a transfer of a permanent right to use a product without additional consideration or to tax the transfer of any use right, such as a use right for a limited period of time or one that is contingent on the continued payment of a subscription or maintenance fee; the state may subject the same product to tax in a different manner depending on the conditions under which the product is transferred.9 Finally, a state that taxes electronically transferred products but provides a product-based exemption for a ‘‘specified digital product’’ must provide a product-based exemption for a functionally equivalent product that is not transferred electronically.10 . SALT Matters Business 1 Equipment and Supplies Purchased Business 2 $300,000 $300,000 Sales Tax Paid 0 15,000 Total Equipment and Supplies Cost 300,000 315,000 Other Costs 600,000 600,000 Total Costs 900,000 915,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 Newspaper Sales Inclusive of Sales Tax Sales Tax Remitted Net Income 0 47,619 100,000 37,381 Source: tables by authors digital equivalents. Finally, states may grace transfers of tangible property with entity-based and usebased exemptions that by default cannot apply to transfers of digital equivalents simply because digital goods and services cannot be defined as tangible property.13 Put simply, if the devil is in the details, the SSUTA provisions for the taxation of digital goods and services smell distinctly of brimstone when it comes to uniformity and fairness, and they fail ‘‘to simplify and modernize sales and use tax administration in the member states in order to substantially reduce the burden of tax compliance.’’14 If the devil is in the details, the SSUTA provisions for the taxation of digital goods and services smell distinctly of brimstone when it comes to uniformity and fairness. Many of the problems inherent in the SSUTA approach to digital goods and services can be best seen through the following example. State X is an SSTP member state that imposes a 5 percent sales tax on the sale of all electronically transferred products, regardless of the nature of the use right transferred and payment terms. State X provides no exemptions for electronically transferred products. State X likewise taxes all sales of tangible property at a 5 percent rate, subject to enumerated exemptions.

State X provides an exemption for sales of newspapers and a broad exemption for purchases of tangible property used in the manufacturing of tangible property, for which newspaper publishers qualify and that applies to energy used in the newspaper production process and many items of tangible property used at least partially for editorial purposes. Business 1 and Business 2 produce com- 13 See, e.g., Georgia Code section 48-8-3.2. SSUTA section 102. 14 State Tax Notes, April 29, 2013 peting local newspapers in State X, generating a total of $1 million in in-state sales, inclusive of sales tax, in the tax year in question. Business 1 and Business 2 both determine the amount they charge for their products by using pricing models based on the maximum price the market will bear, inclusive of sales tax.

Business 1 and Business 2 have physical plant and employees in State X, make $300,000 in in-state purchases of equipment and supplies used in newspaper production in the tax year in question, and incur $600,000 in additional costs. The only appreciable difference between Business 1 and Business 2 is that Business 1 delivers its newspaper 100 percent via the transfer of tangible property, while Business 2 delivers its newspaper electronically by subscription via digital download or e-mail.15 The State X sales tax effect on Business 1 and Business 2 in Table 1. In this scenario, the sales tax imposed on Business 2’s purchases of equipment and supplies and the sales tax collected and remitted on its sales of digital newspapers result in a direct hit to the profitability of Business 2, making Business 1 a more attractive investment. Because its product is a commodity and prices cannot be raised, Business 2’s likely response would be to enhance net income by cutting costs (for example, salaries, bonuses, advertising, research, development of new products, purchases of equipment and supplies, and so on) by approximately $63,000. In turn, that reduction in 15 Clearly, this example does not represent a real-world scenario, because equipment and supply costs for a Webbased newspaper would generally be demonstrably lower than for a tangible newspaper; however, margins may be substantially similar, as other costs would be nearly the same, and subscription numbers and subscription price for an online local newspaper would likely be lower.

Accordingly, although not perfectly representative, a one-to-one comparison in which the only differential is sales tax paid and charged is valuable and instructive. 367 (C) Tax Analysts 2013. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. Table 1. .

SALT Matters Business 1 Equipment and Supplies Purchased Business 2 $300,000 $300,000 Sales Tax Paid 0 15,000 Total Equipment and Supplies Cost 300,000 315,000 Other Costs 600,000 600,000 Total Costs 900,000 915,000 1,000,000 1,065,750 Newspaper Sales Inclusive of Sales Tax Sales Tax Remitted Net Income Sales Tax Charged on Sales Tax Paid 0 50,750 100,000 100,000 0 750 Source: tables by authors spending would have a negative economic effect on both incomes and the tax base. The applicable law and facts produce even worse results in a non-commodity situation that would allow Business 2 to raise its prices to push the effect of the sales tax onto its customers. Assume, for example, that consumers of newspapers in State X strongly prefer digital delivery and are willing to pay a premium that would offset the sales tax imposed on Business 2’s taxable purchases and sales. The State X sales tax effect in that revised scenario in Table 2. In this scenario, Business 1 and Business 2 have the same net income, but Business 2’s customers must pay more for a newspaper solely because of sales tax based on the method of delivery. Furthermore, tax is imposed at multiple levels, resulting in tax pyramiding. There must be a better answer. Taxing Digital Goods and Services as Tangible Property One possible alternative to the SSUTA approach is for states to move past the artificial distinction between goods and services delivered via tangible property and by electronic means, and to focus instead on the incidence of consumption by looking solely to the true object of each transaction.16 To do 16 The ‘‘true object of the transaction’’ would be determined by examining two questions: (1) whether the consumer wants the data/service/skill regardless of the method of delivery; and (2) whether the data/service/skill is substantially equivalent regardless of the method of delivery. If so, the sales tax treatment of the data/service/skill would have to be the same regardless of the method of delivery.

That method is a modernized offshoot of the true object test now applied to determine whether a sale of mixed services, intangibles, and tangible property should be taxed as a sale of tangible property, and should be familiar and accessible to taxpayers and taxing authorities alike. 368 that, a state would have to include all goods and services, regardless of the method of delivery, within the definition of tangible property, and provide exemptions based on the purchaser, use, or product that reference tangible property in general or the product subject to consumption in particular. Then taxability determinations would be driven by the nature of the seller/producer, the nature of the consumer, the purpose to which the consumer intends to put the product, or the nature of the product, and not by the method by which the product was delivered.17 Again, an example is illustrative. State X withdraws from the SSTP, and repeals the SSUTA tax imposition statutes discussed above.

In their place, State X enacts a law that defines all sales of goods and services, regardless of the method of delivery, as tangible personal property, and provides that the ‘‘true object of the transaction’’ test will apply to all sales to determine what has been purchased and whether exemptions apply. State X continues to tax all sales of tangible property at a 5 percent rate and provides the same exemptions as discussed above. The facts and circumstances for Business 1 and Business 2 are the same as in the original example. 17 To some extent, that approach has been adopted by a number of states and has proved successful both in terms of generating revenue from previously untaxed sales of digital goods and services and equalizing treatment between sales of tangible property and digital equivalents. For example, Louisiana, in accordance with 61 LAC Reg.

4301, provides that the sale of a digital product such as music, movies, books, games, and electronic files, regardless of the method of delivery, is a taxable transaction because those items fall within the definition of tangible personal property. Clearly, sellers of these products to consumers would be required to collect and remit sales tax in the same manner as if they had sold the same digital product on a tangible medium; however, exemptions would apply equally to both. For example, the newspaper exclusion under LA R.S.

section 47:301(16)(p) would apply to exempt sales of digital newspapers in the same manner as it exempts sales of tangible newspapers. State Tax Notes, April 29, 2013 (C) Tax Analysts 2013. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. Table 2. .

SALT Matters Business 1 Equipment and Supplies Purchased Business 2 $300,000 $300,000 Sales Tax Paid 0 0 Total Equipment and Supplies Cost 300,000 300,000 Other Costs 600,000 600,000 Total Costs 900,000 900,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 Newspaper Sales Inclusive of Sales Tax Sales Tax Remitted Net Income 0 0 100,000 100,000 Source: tables by authors Business 2, wary of the sales tax treatment it received under the SSUTA regime, requests guidance from State X regarding the applicability of the broad manufacturing exemption to its purchases of tangible property for use in producing its digital newspaper and the applicability of the newspaper exemption to its sales of digital newspaper subscriptions to consumers. Based on its new statutory framework and using the ‘‘true object of the transaction’’ test, State X determines that the purpose of a consumer in purchasing a newspaper is to read the news, and finds that this purpose is served regardless of whether the consumer purchases a tangible newspaper or digital equivalent. Accordingly, State X advises Business 2 that it will be treated as a newspaper publisher and its product will be treated as a newspaper, qualifying its purchases and sales for both exemptions at issue. The State X sales tax effect on Business 1 and Business 2 in this scenario in Table 3. In this scenario, the sales tax treatment of a digital newspaper is the same as equivalent tangible property. No sales tax is paid by either newspaper publisher on purchases of equipment and supplies, and no sales tax is charged to consumers.

Taken as a whole, the net result is a level playing field on which the producers of equivalent products earn the same amount of net income under essentially the same facts and circumstances, and sales tax is eliminated as the crucial factor in determining economic winners and losers. Most importantly, consumers can choose based solely on product utility and aesthetic factors, not on price or quality differences driven by inequitable sales tax treatment. ices to sales tax is untenable. Uniformity, fairness, simplicity, and, therefore, compliance have all suffered because SSTP member states apply the SSUTA framework with little consistency (except for excluding digital goods from the definition of tangible property), while other states apply the tangible property approach piecemeal, or avoid the question by not addressing the sales tax treatment of digital goods and services at all.

As illustrated, the proposed cure offered by Mazerov — the universal adoption of the SSUTA — provides no relief from any of those problems, and it should be abandoned in favor of defining digital goods and services as tangible property and approaching the sales tax treatment of those products based on the consumer’s true object in purchasing them. ✰ Brian J. Kirkell is a director in the Washington National Tax office of McGladrey LLP. Brad Hershberger is a partner in McGladrey’s State and Local Tax Practice in Des Moines, Iowa. The information contained herein is general in nature and based on authorities that are subject to change.

This publication does not, and is not intended to, provide legal, tax, or accounting advice, and readers should consult their tax advisers concerning the application of tax laws to their particular situations. This analysis is not tax advice and is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for purposes of avoiding tax penalties that may be imposed on any taxpayer. This article represents the views of the authors only, and does not necessarily represent the views or professional advice of McGladrey. Conclusion There can be little doubt that the status quo in terms of subjecting sales of digital goods and serv- State Tax Notes, April 29, 2013 369 (C) Tax Analysts 2013. All rights reserved.

Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. Table 3. .