Description

GOLD AND INFLATION HEDGES

Q1 2011

1

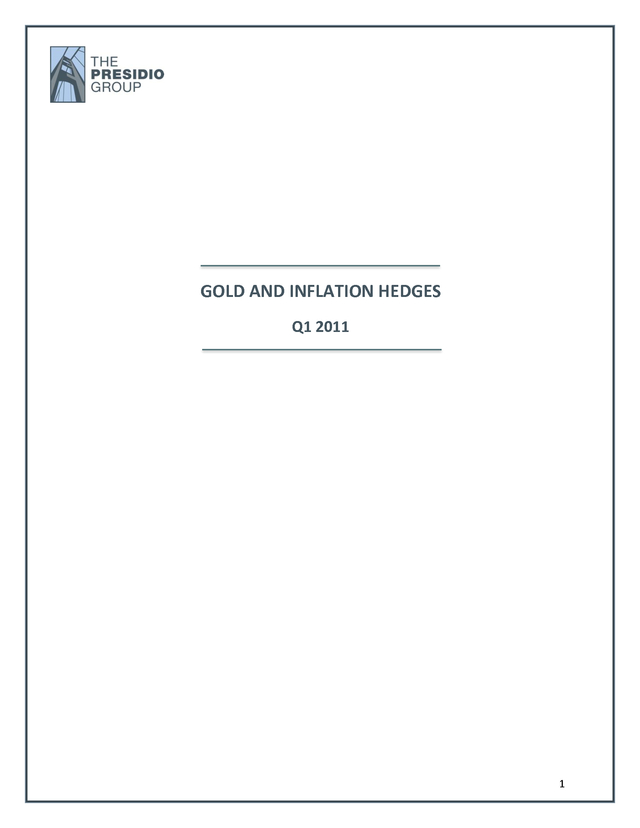

. For the past decade gold has been the asset allocator’s Holy Grail. It has outperformed all of the major

asset classes over the past ten years, as the chart below illustrates.

Asset Class Performance: Jan-2001 to Mar-2011

500%

Cumulative Return

400%

Average

Annual

Return

300%

Correlation to

Worst

One-year 60% Stock/ 40%

Return Bond Portfolio

Gold

-9%

0.20

8.3%

-33%

0.69

US Treasuries

100%

17.6%

High yield bonds

200%

01

02

03

04

05

06

-100%

07

08

09

10

11

5.3%

-10%

0.00

Commodity futures 2.8%

0%

-60%

0.37

Stocks

-49%

0.95

1.7%

Source: Bloomberg, JP Morgan, MSCI

Not only did the yellow metal generate much higher returns than stocks, bonds, and most other

commodities—it did so with remarkable consistency and low correlation. Gold has gone up every

calendar year since 2001; the worst 12-month return over that period was -9%. It has served as an

excellent diversifier to stocks and bonds, rising during several periods when these traditional

components of investors’ portfolios declined.

Not surprisingly, the steady rise in gold prices has caused its appeal to expand beyond the “shotguns and

bottled water” set and into the mainstream.

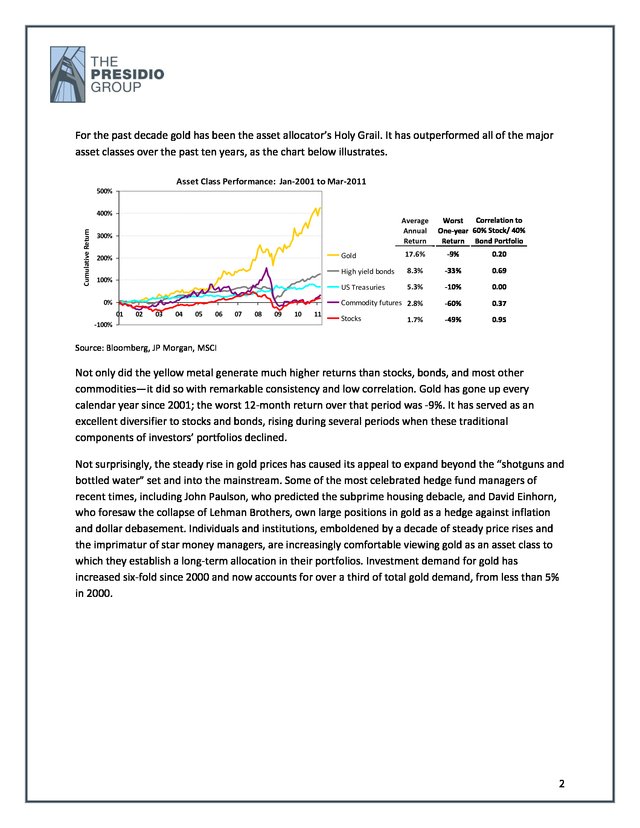

Some of the most celebrated hedge fund managers of recent times, including John Paulson, who predicted the subprime housing debacle, and David Einhorn, who foresaw the collapse of Lehman Brothers, own large positions in gold as a hedge against inflation and dollar debasement. Individuals and institutions, emboldened by a decade of steady price rises and the imprimatur of star money managers, are increasingly comfortable viewing gold as an asset class to which they establish a long-term allocation in their portfolios. Investment demand for gold has increased six-fold since 2000 and now accounts for over a third of total gold demand, from less than 5% in 2000. 2 .

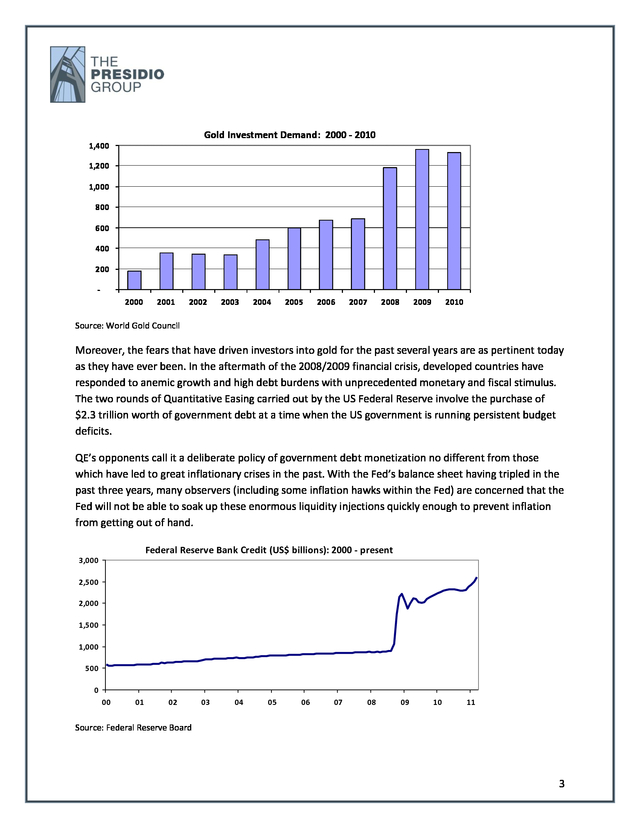

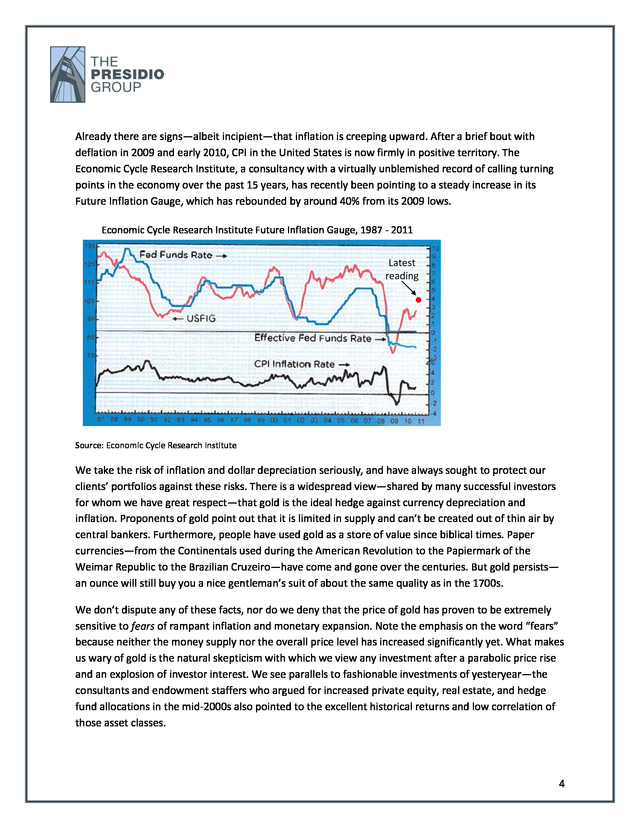

Gold Investment Demand: 2000 - 2010 1,400 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Source: World Gold Council Moreover, the fears that have driven investors into gold for the past several years are as pertinent today as they have ever been. In the aftermath of the 2008/2009 financial crisis, developed countries have responded to anemic growth and high debt burdens with unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus. The two rounds of Quantitative Easing carried out by the US Federal Reserve involve the purchase of $2.3 trillion worth of government debt at a time when the US government is running persistent budget deficits. QE’s opponents call it a deliberate policy of government debt monetization no different from those which have led to great inflationary crises in the past. With the Fed’s balance sheet having tripled in the past three years, many observers (including some inflation hawks within the Fed) are concerned that the Fed will not be able to soak up these enormous liquidity injections quickly enough to prevent inflation from getting out of hand. Federal Reserve Bank Credit (US$ billions): 2000 - present 3,000 2,500 2,000 1,500 1,000 500 0 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 Source: Federal Reserve Board 3 . Already there are signs—albeit incipient—that inflation is creeping upward. After a brief bout with deflation in 2009 and early 2010, CPI in the United States is now firmly in positive territory. The Economic Cycle Research Institute, a consultancy with a virtually unblemished record of calling turning points in the economy over the past 15 years, has recently been pointing to a steady increase in its Future Inflation Gauge, which has rebounded by around 40% from its 2009 lows. Economic Cycle Research Institute Future Inflation Gauge, 1987 - 2011 Latest reading Source: Economic Cycle Research Institute We take the risk of inflation and dollar depreciation seriously, and have always sought to protect our clients’ portfolios against these risks. There is a widespread view—shared by many successful investors for whom we have great respect—that gold is the ideal hedge against currency depreciation and inflation.

Proponents of gold point out that it is limited in supply and can’t be created out of thin air by central bankers. Furthermore, people have used gold as a store of value since biblical times. Paper currencies—from the Continentals used during the American Revolution to the Papiermark of the Weimar Republic to the Brazilian Cruzeiro—have come and gone over the centuries.

But gold persists— an ounce will still buy you a nice gentleman’s suit of about the same quality as in the 1700s. We don’t dispute any of these facts, nor do we deny that the price of gold has proven to be extremely sensitive to fears of rampant inflation and monetary expansion. Note the emphasis on the word “fears” because neither the money supply nor the overall price level has increased significantly yet. What makes us wary of gold is the natural skepticism with which we view any investment after a parabolic price rise and an explosion of investor interest.

We see parallels to fashionable investments of yesteryear—the consultants and endowment staffers who argued for increased private equity, real estate, and hedge fund allocations in the mid-2000s also pointed to the excellent historical returns and low correlation of those asset classes. 4 . Compounding our concerns over gold is the fact that it has little or no inherent value outside of the monetary function it has played historically. Other than jewelry, gold has no real practical use, and it produces no cash flow. In fact, once you factor in insurance and storage there is a net cost to owning gold. Because of this, it is impossible to value gold or to ascertain the extent to which the inflationary scenario we all fear is already baked into its price today. One of the core tenets of our investment philosophy is encapsulated in the trader’s axiom “there are no bad bonds, only bad prices.” In investing it is not enough to know that Apple will sell a lot of iPhones or that the internet will transform the way we do business or that emerging market companies will earn big profits.

If one overpays for any of those highly probable outcomes, one has made a poor investment. For example, Wal-Mart has largely delivered on its goal of revolutionizing retail over the past decade. Yet investors who bought the stock at $52 in 2001 have no gains to show for it today because the company’s bright future was already reflected in the stock’s price at that time. We try to keep this principle in mind as we ponder the question of whether or not to invest in gold today. Yes, gold has proven to be a good dollar and inflation hedge in the past. And yes, dollar depreciation and inflation are very real risks.

But because gold cannot be valued, it is impossible to know if one is underpaying or overpaying for this historically reliable inflation hedge. Noted investor Howard Marks illustrates this point in his recounting of a conversation with a gold bug: Howard: How do you feel about gold here at $1,400 an ounce? Gold bug: Great. I ’m sure it will hold its value from here and keep up with inflation Howard: Would you be equally sure if it were $2,000? Gold bug: A little less, but yes. Howard: At $5,000? Gold bug: That’s a tough one. Howard: And at $10,000? Gold bug: No; there it would be ahead of itself. Howard: So the price of gold matters? Gold bug: Sure. Howard: Then how can you be sure it’s fairly priced at $1,400? Gold bug: Hmm .

. . .

. 5 . Source: Howard Marks, “All That Glitters” Perhaps this is why arguments for gold often rest on some version of the “greater fool” theory—that is, the notion that gold will keep going up because it will continue to attract new buyers. Marc Faber, editor of the Gloom Boom & Doom Report, likes to ask audiences at conferences to raise their hands if they have more than 5% of their personal assets in gold. When nobody does, he argues that gold is still an under-owned asset with plenty of upside1. For the past several years, Faber and other proponents of gold have been dead right—the number of investors interested in owning gold has steadily grown, as radio ads and infomercials touting the shiny metal fill the airwaves. It may very well be that this trend continues, as Ben Bernanke and his closest allies within the Fed show no signs of renouncing their dovishness on inflation.

But we are not comfortable owning any asset on the premise that it will attract new buyers in the future, particularly when that asset cannot be valued and we have no insight as to when demand by new buyers might wane. So, in a world that has been fretting over the possibility of inflation and dollar depreciation for several years, where can a valuation-sensitive investor find “cheap” hedges? As an illustration of how we think about risk management, we review a series of investments and strategic changes that we have employed over the past couple of years: Municipal Inflation Protected Bonds are a small, unique market that presently affords high net worth individuals a real yield-to-maturity of over 2% plus trailing CPI all shielded from Federal taxes. What this means is that if CPI were to accelerate, say to the 5% level, the coupon on these bonds would likely adjust upwards by a similar amount. Yet if we do experience deflation much as we did in 2008 the bond holder will eventually get par plus the real coupons on the bond. Inflation swaps allow investors to take a position on the rate of change of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) over a specified period of time. The “receiver” of inflation in this transaction will profit if actual CPI exceeds a certain breakeven inflation rate and will lose money if actual CPI comes in below that amount. By way of perspective, it was only a couple of years ago that Faber’s question to audiences was whether they owned gold at all.

Inevitably when few hands went up he claimed that gold was an under-owned asset. These days he has reframed the question to qualify the holding to be more than 5%. We wonder how long it will be before Faber begins asking how many people have at least 10% of their assets in gold. 6 .

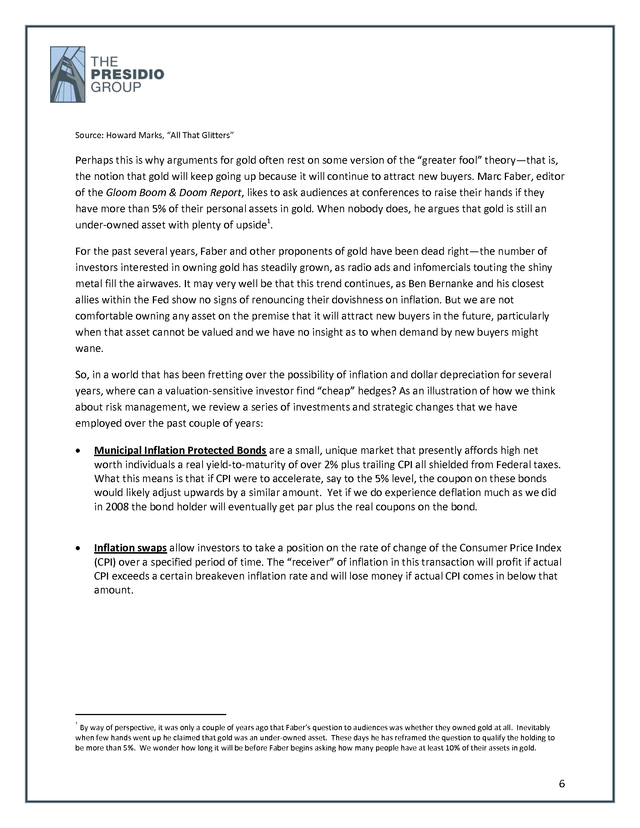

10-Year CPI Swap Breakeven Inflation Rate 3.5% 3.0% April 2011: 2.83% 2.5% 2.0% 1.5% 1.0% 0.5% 0.0% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Source: JP Morgan As shown in the chart above, at the moment the receiver of inflation in a CPI swap transaction will profit if inflation over the next 10 years exceeds 2.8%. Six months ago, the risk/return proposition in CPI swaps was even more attractive: 10-year inflation needed only to exceed 2% for the receiver of inflation to make money. This is an exposure that we added to many client portfolios in the middle of 2010 through a fund that invests part of its assets in CPI swaps. We continue to view CPI swaps as an attractive way to build inflation protection into a portfolio. Emerging market currencies - as discussed in our April 2010 white paper, a number of emerging market countries enjoy superior fundamentals when compared to the US and other developed countries.

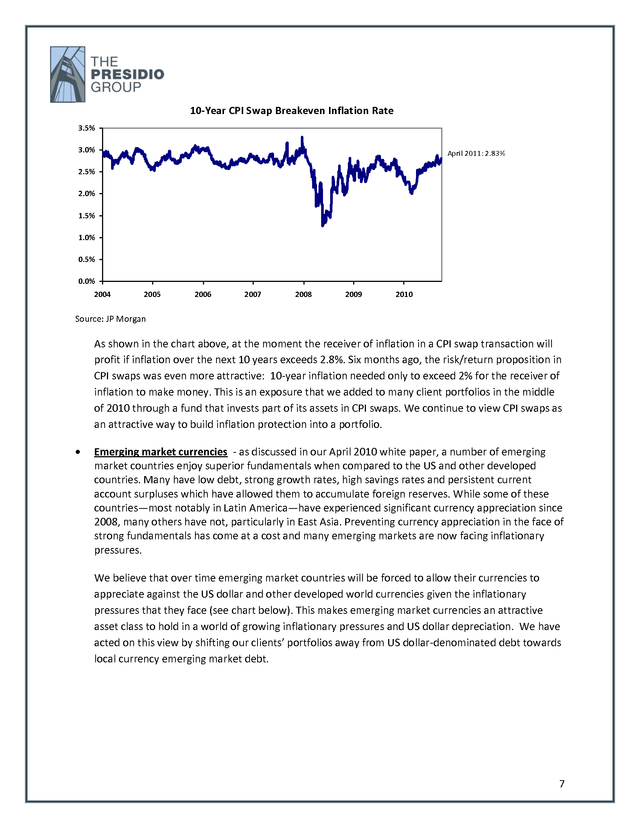

Many have low debt, strong growth rates, high savings rates and persistent current account surpluses which have allowed them to accumulate foreign reserves. While some of these countries—most notably in Latin America—have experienced significant currency appreciation since 2008, many others have not, particularly in East Asia. Preventing currency appreciation in the face of strong fundamentals has come at a cost and many emerging markets are now facing inflationary pressures. We believe that over time emerging market countries will be forced to allow their currencies to appreciate against the US dollar and other developed world currencies given the inflationary pressures that they face (see chart below).

This makes emerging market currencies an attractive asset class to hold in a world of growing inflationary pressures and US dollar depreciation. We have acted on this view by shifting our clients’ portfolios away from US dollar-denominated debt towards local currency emerging market debt. 7 . Source: JP Morgan Interest-only mortgage strips – “IO” strips of mortgage-backed securities entitle their owners to a stream of future interest payments from a pool of mortgages. Because of this feature, IOs tend to rise in price when homeowners are unwilling or unable to refinance their mortgages (because the stream of interest payments that the IO owner collects is extended), and tend to fall in price when the rate of mortgage refinancing exceeds the market’s expectations (because refinancings extinguish future interest payments). Interest-only strips are unique among fixed income assets in that they have negative duration; that is, their prices tend to increase when interest rates increase (other things equal). At the same time, at current prices it is possible to construct a portfolio of interest-only mortgage strips that generates significant monthly income. In other words, an IO investor can earn a reasonable rate of return while holding an asset that would react positively to an increase in long-term interest rates.

Many of our clients have exposure to interest-only mortgage strips through a mortgage arbitrage hedge fund with whom we have invested since 2008. This same manager recently launched a dedicated strategy designed to serve as an explicit hedge against inflationary Fed policies. To be clear, our purpose here is not to state that gold is overpriced or in a bubble, as some have argued. However, we do suspect that many investors who have recently bought gold have focused on recent performance rather than the longer-term history of the asset. The chart below provides some perspective.

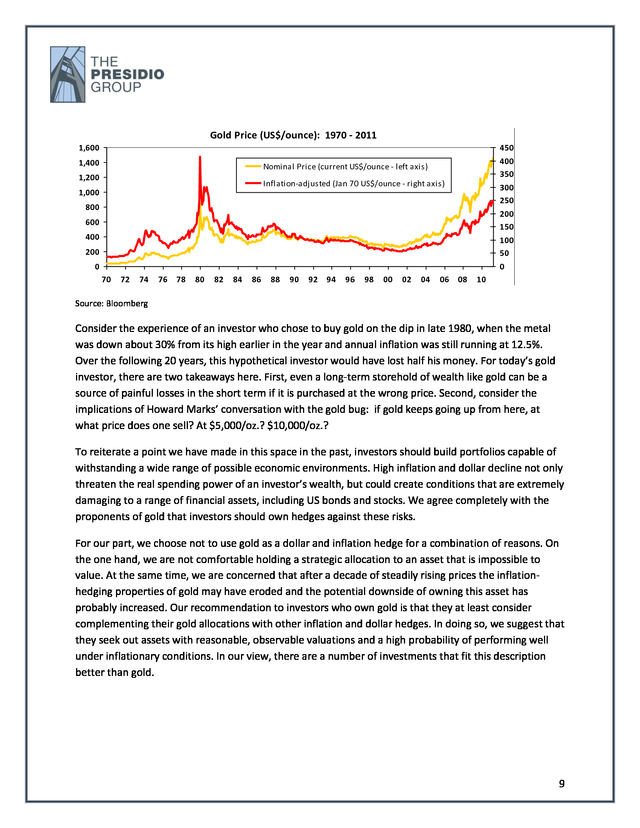

Gold traded at a fixed price of $35/ounce between the end of World War II and 1971, when Nixon ended the gold standard. It spiked in 1975 and again in 1980, when it briefly touched a peak of $850 amid double-digit inflation and geopolitical turmoil in Iran and Afghanistan. In inflation-adjusted terms, today’s price is still around 15% lower than the average price that prevailed in 1980. 8 .

Gold Price (US$/ounce): 1970 - 2011 1,600 450 1,400 400 350 Nominal Price (current US$/ounce - left axis) 1,200 Inflation-adjusted (Jan 70 US$/ounce - right axis) 300 250 1,000 800 200 150 600 400 100 50 200 0 0 70 72 74 76 78 80 82 84 86 88 90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 Source: Bloomberg Consider the experience of an investor who chose to buy gold on the dip in late 1980, when the metal was down about 30% from its high earlier in the year and annual inflation was still running at 12.5%. Over the following 20 years, this hypothetical investor would have lost half his money. For today’s gold investor, there are two takeaways here. First, even a long-term storehold of wealth like gold can be a source of painful losses in the short term if it is purchased at the wrong price. Second, consider the implications of Howard Marks’ conversation with the gold bug: if gold keeps going up from here, at what price does one sell? At $5,000/oz.? $10,000/oz.? To reiterate a point we have made in this space in the past, investors should build portfolios capable of withstanding a wide range of possible economic environments.

High inflation and dollar decline not only threaten the real spending power of an investor’s wealth, but could create conditions that are extremely damaging to a range of financial assets, including US bonds and stocks. We agree completely with the proponents of gold that investors should own hedges against these risks. For our part, we choose not to use gold as a dollar and inflation hedge for a combination of reasons. On the one hand, we are not comfortable holding a strategic allocation to an asset that is impossible to value.

At the same time, we are concerned that after a decade of steadily rising prices the inflationhedging properties of gold may have eroded and the potential downside of owning this asset has probably increased. Our recommendation to investors who own gold is that they at least consider complementing their gold allocations with other inflation and dollar hedges. In doing so, we suggest that they seek out assets with reasonable, observable valuations and a high probability of performing well under inflationary conditions.

In our view, there are a number of investments that fit this description better than gold. 9 .

Some of the most celebrated hedge fund managers of recent times, including John Paulson, who predicted the subprime housing debacle, and David Einhorn, who foresaw the collapse of Lehman Brothers, own large positions in gold as a hedge against inflation and dollar debasement. Individuals and institutions, emboldened by a decade of steady price rises and the imprimatur of star money managers, are increasingly comfortable viewing gold as an asset class to which they establish a long-term allocation in their portfolios. Investment demand for gold has increased six-fold since 2000 and now accounts for over a third of total gold demand, from less than 5% in 2000. 2 .

Gold Investment Demand: 2000 - 2010 1,400 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Source: World Gold Council Moreover, the fears that have driven investors into gold for the past several years are as pertinent today as they have ever been. In the aftermath of the 2008/2009 financial crisis, developed countries have responded to anemic growth and high debt burdens with unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus. The two rounds of Quantitative Easing carried out by the US Federal Reserve involve the purchase of $2.3 trillion worth of government debt at a time when the US government is running persistent budget deficits. QE’s opponents call it a deliberate policy of government debt monetization no different from those which have led to great inflationary crises in the past. With the Fed’s balance sheet having tripled in the past three years, many observers (including some inflation hawks within the Fed) are concerned that the Fed will not be able to soak up these enormous liquidity injections quickly enough to prevent inflation from getting out of hand. Federal Reserve Bank Credit (US$ billions): 2000 - present 3,000 2,500 2,000 1,500 1,000 500 0 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 Source: Federal Reserve Board 3 . Already there are signs—albeit incipient—that inflation is creeping upward. After a brief bout with deflation in 2009 and early 2010, CPI in the United States is now firmly in positive territory. The Economic Cycle Research Institute, a consultancy with a virtually unblemished record of calling turning points in the economy over the past 15 years, has recently been pointing to a steady increase in its Future Inflation Gauge, which has rebounded by around 40% from its 2009 lows. Economic Cycle Research Institute Future Inflation Gauge, 1987 - 2011 Latest reading Source: Economic Cycle Research Institute We take the risk of inflation and dollar depreciation seriously, and have always sought to protect our clients’ portfolios against these risks. There is a widespread view—shared by many successful investors for whom we have great respect—that gold is the ideal hedge against currency depreciation and inflation.

Proponents of gold point out that it is limited in supply and can’t be created out of thin air by central bankers. Furthermore, people have used gold as a store of value since biblical times. Paper currencies—from the Continentals used during the American Revolution to the Papiermark of the Weimar Republic to the Brazilian Cruzeiro—have come and gone over the centuries.

But gold persists— an ounce will still buy you a nice gentleman’s suit of about the same quality as in the 1700s. We don’t dispute any of these facts, nor do we deny that the price of gold has proven to be extremely sensitive to fears of rampant inflation and monetary expansion. Note the emphasis on the word “fears” because neither the money supply nor the overall price level has increased significantly yet. What makes us wary of gold is the natural skepticism with which we view any investment after a parabolic price rise and an explosion of investor interest.

We see parallels to fashionable investments of yesteryear—the consultants and endowment staffers who argued for increased private equity, real estate, and hedge fund allocations in the mid-2000s also pointed to the excellent historical returns and low correlation of those asset classes. 4 . Compounding our concerns over gold is the fact that it has little or no inherent value outside of the monetary function it has played historically. Other than jewelry, gold has no real practical use, and it produces no cash flow. In fact, once you factor in insurance and storage there is a net cost to owning gold. Because of this, it is impossible to value gold or to ascertain the extent to which the inflationary scenario we all fear is already baked into its price today. One of the core tenets of our investment philosophy is encapsulated in the trader’s axiom “there are no bad bonds, only bad prices.” In investing it is not enough to know that Apple will sell a lot of iPhones or that the internet will transform the way we do business or that emerging market companies will earn big profits.

If one overpays for any of those highly probable outcomes, one has made a poor investment. For example, Wal-Mart has largely delivered on its goal of revolutionizing retail over the past decade. Yet investors who bought the stock at $52 in 2001 have no gains to show for it today because the company’s bright future was already reflected in the stock’s price at that time. We try to keep this principle in mind as we ponder the question of whether or not to invest in gold today. Yes, gold has proven to be a good dollar and inflation hedge in the past. And yes, dollar depreciation and inflation are very real risks.

But because gold cannot be valued, it is impossible to know if one is underpaying or overpaying for this historically reliable inflation hedge. Noted investor Howard Marks illustrates this point in his recounting of a conversation with a gold bug: Howard: How do you feel about gold here at $1,400 an ounce? Gold bug: Great. I ’m sure it will hold its value from here and keep up with inflation Howard: Would you be equally sure if it were $2,000? Gold bug: A little less, but yes. Howard: At $5,000? Gold bug: That’s a tough one. Howard: And at $10,000? Gold bug: No; there it would be ahead of itself. Howard: So the price of gold matters? Gold bug: Sure. Howard: Then how can you be sure it’s fairly priced at $1,400? Gold bug: Hmm .

. . .

. 5 . Source: Howard Marks, “All That Glitters” Perhaps this is why arguments for gold often rest on some version of the “greater fool” theory—that is, the notion that gold will keep going up because it will continue to attract new buyers. Marc Faber, editor of the Gloom Boom & Doom Report, likes to ask audiences at conferences to raise their hands if they have more than 5% of their personal assets in gold. When nobody does, he argues that gold is still an under-owned asset with plenty of upside1. For the past several years, Faber and other proponents of gold have been dead right—the number of investors interested in owning gold has steadily grown, as radio ads and infomercials touting the shiny metal fill the airwaves. It may very well be that this trend continues, as Ben Bernanke and his closest allies within the Fed show no signs of renouncing their dovishness on inflation.

But we are not comfortable owning any asset on the premise that it will attract new buyers in the future, particularly when that asset cannot be valued and we have no insight as to when demand by new buyers might wane. So, in a world that has been fretting over the possibility of inflation and dollar depreciation for several years, where can a valuation-sensitive investor find “cheap” hedges? As an illustration of how we think about risk management, we review a series of investments and strategic changes that we have employed over the past couple of years: Municipal Inflation Protected Bonds are a small, unique market that presently affords high net worth individuals a real yield-to-maturity of over 2% plus trailing CPI all shielded from Federal taxes. What this means is that if CPI were to accelerate, say to the 5% level, the coupon on these bonds would likely adjust upwards by a similar amount. Yet if we do experience deflation much as we did in 2008 the bond holder will eventually get par plus the real coupons on the bond. Inflation swaps allow investors to take a position on the rate of change of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) over a specified period of time. The “receiver” of inflation in this transaction will profit if actual CPI exceeds a certain breakeven inflation rate and will lose money if actual CPI comes in below that amount. By way of perspective, it was only a couple of years ago that Faber’s question to audiences was whether they owned gold at all.

Inevitably when few hands went up he claimed that gold was an under-owned asset. These days he has reframed the question to qualify the holding to be more than 5%. We wonder how long it will be before Faber begins asking how many people have at least 10% of their assets in gold. 6 .

10-Year CPI Swap Breakeven Inflation Rate 3.5% 3.0% April 2011: 2.83% 2.5% 2.0% 1.5% 1.0% 0.5% 0.0% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Source: JP Morgan As shown in the chart above, at the moment the receiver of inflation in a CPI swap transaction will profit if inflation over the next 10 years exceeds 2.8%. Six months ago, the risk/return proposition in CPI swaps was even more attractive: 10-year inflation needed only to exceed 2% for the receiver of inflation to make money. This is an exposure that we added to many client portfolios in the middle of 2010 through a fund that invests part of its assets in CPI swaps. We continue to view CPI swaps as an attractive way to build inflation protection into a portfolio. Emerging market currencies - as discussed in our April 2010 white paper, a number of emerging market countries enjoy superior fundamentals when compared to the US and other developed countries.

Many have low debt, strong growth rates, high savings rates and persistent current account surpluses which have allowed them to accumulate foreign reserves. While some of these countries—most notably in Latin America—have experienced significant currency appreciation since 2008, many others have not, particularly in East Asia. Preventing currency appreciation in the face of strong fundamentals has come at a cost and many emerging markets are now facing inflationary pressures. We believe that over time emerging market countries will be forced to allow their currencies to appreciate against the US dollar and other developed world currencies given the inflationary pressures that they face (see chart below).

This makes emerging market currencies an attractive asset class to hold in a world of growing inflationary pressures and US dollar depreciation. We have acted on this view by shifting our clients’ portfolios away from US dollar-denominated debt towards local currency emerging market debt. 7 . Source: JP Morgan Interest-only mortgage strips – “IO” strips of mortgage-backed securities entitle their owners to a stream of future interest payments from a pool of mortgages. Because of this feature, IOs tend to rise in price when homeowners are unwilling or unable to refinance their mortgages (because the stream of interest payments that the IO owner collects is extended), and tend to fall in price when the rate of mortgage refinancing exceeds the market’s expectations (because refinancings extinguish future interest payments). Interest-only strips are unique among fixed income assets in that they have negative duration; that is, their prices tend to increase when interest rates increase (other things equal). At the same time, at current prices it is possible to construct a portfolio of interest-only mortgage strips that generates significant monthly income. In other words, an IO investor can earn a reasonable rate of return while holding an asset that would react positively to an increase in long-term interest rates.

Many of our clients have exposure to interest-only mortgage strips through a mortgage arbitrage hedge fund with whom we have invested since 2008. This same manager recently launched a dedicated strategy designed to serve as an explicit hedge against inflationary Fed policies. To be clear, our purpose here is not to state that gold is overpriced or in a bubble, as some have argued. However, we do suspect that many investors who have recently bought gold have focused on recent performance rather than the longer-term history of the asset. The chart below provides some perspective.

Gold traded at a fixed price of $35/ounce between the end of World War II and 1971, when Nixon ended the gold standard. It spiked in 1975 and again in 1980, when it briefly touched a peak of $850 amid double-digit inflation and geopolitical turmoil in Iran and Afghanistan. In inflation-adjusted terms, today’s price is still around 15% lower than the average price that prevailed in 1980. 8 .

Gold Price (US$/ounce): 1970 - 2011 1,600 450 1,400 400 350 Nominal Price (current US$/ounce - left axis) 1,200 Inflation-adjusted (Jan 70 US$/ounce - right axis) 300 250 1,000 800 200 150 600 400 100 50 200 0 0 70 72 74 76 78 80 82 84 86 88 90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 Source: Bloomberg Consider the experience of an investor who chose to buy gold on the dip in late 1980, when the metal was down about 30% from its high earlier in the year and annual inflation was still running at 12.5%. Over the following 20 years, this hypothetical investor would have lost half his money. For today’s gold investor, there are two takeaways here. First, even a long-term storehold of wealth like gold can be a source of painful losses in the short term if it is purchased at the wrong price. Second, consider the implications of Howard Marks’ conversation with the gold bug: if gold keeps going up from here, at what price does one sell? At $5,000/oz.? $10,000/oz.? To reiterate a point we have made in this space in the past, investors should build portfolios capable of withstanding a wide range of possible economic environments.

High inflation and dollar decline not only threaten the real spending power of an investor’s wealth, but could create conditions that are extremely damaging to a range of financial assets, including US bonds and stocks. We agree completely with the proponents of gold that investors should own hedges against these risks. For our part, we choose not to use gold as a dollar and inflation hedge for a combination of reasons. On the one hand, we are not comfortable holding a strategic allocation to an asset that is impossible to value.

At the same time, we are concerned that after a decade of steadily rising prices the inflationhedging properties of gold may have eroded and the potential downside of owning this asset has probably increased. Our recommendation to investors who own gold is that they at least consider complementing their gold allocations with other inflation and dollar hedges. In doing so, we suggest that they seek out assets with reasonable, observable valuations and a high probability of performing well under inflationary conditions.

In our view, there are a number of investments that fit this description better than gold. 9 .