Protecting Fashion through Copyrights: The Supreme Court Will Decide Whether Cheer Uniform Designs Are Protectable – May 11, 2016

Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman

Description

Client Alert

Intellectual Property

Intellectual Property

Copyrights

May 11, 2016

Protecting Fashion through Copyrights: The

Supreme Court Will Decide Whether Cheer

Uniform Designs Are Protectable

By Lori Levine, Jeffrey D. Wexler and Bobby Ghajar

Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court announced that it will address the issue

whether apparel can be protected by copyright law—a question described by

the petitioners in the case as “the single most vexing, unresolved question in all

of copyright.” The justices will consider the ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit in Varsity Brands, Inc.

v. Star Athletica, LLC, that the stripes, chevrons, zigzags, and color blocks that appear on a cheerleading uniform are protectable under the copyright laws. Fashion designs have traditionally had very limited protection under U.S. copyright law, which protects “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.” For a work to be considered original, it must be independently created by its author, and possess at least some minimal degree of creativity.

Certainly, clothing designs fall within this ambit of protection. However, the reason why clothing designs have been afforded relatively little protection under copyright law is that copyright protection does not apply to items that serve a utilitarian function. For example, a white t-shirt cannot garner copyright protection because the t-shirt is a useful item with no separately artistic element.

The only way for the design of a garment to acquire copyright protection is if the design “can be identified separately from, and [is] capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.” What this means has been the subject of much confusion and debate. In Varsity Brands, Inc., plaintiff Varsity, a company in the business of designing and manufacturing athletic apparel, had received several copyright registrations for much of its “two-dimensional artwork” for many of its designs for cheerleading outfits. In its complaint, Varsity alleged five claims of copyright infringement against defendant Star for selling cheerleading uniforms that were alleged to be substantially similar to Varsity’s designs. In response, at summary judgment, Star claimed that Varsity did not have a valid copyright in its designs because: (1) Varsity’s designs are for useful articles and are therefore not copyrightable; and (2) the pictorial, graphic, or sculptural elements of Varsity’s designs were not physically or conceptually separable from the uniforms, making the designs ineligible for copyright protection. Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP pillsburylaw.com | 1 .

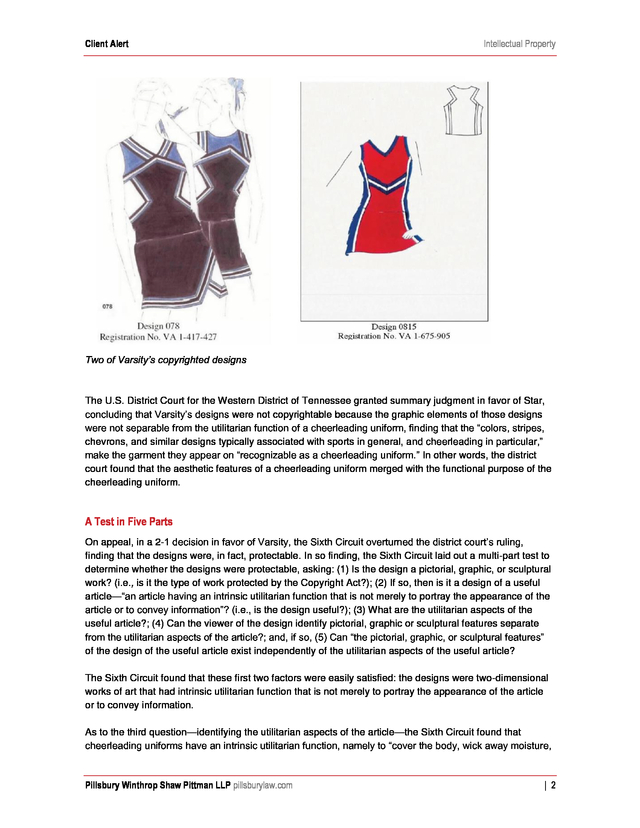

Client Alert Intellectual Property Two of Varsity’s copyrighted designs The U.S. District Court for the Western District of Tennessee granted summary judgment in favor of Star, concluding that Varsity’s designs were not copyrightable because the graphic elements of those designs were not separable from the utilitarian function of a cheerleading uniform, finding that the “colors, stripes, chevrons, and similar designs typically associated with sports in general, and cheerleading in particular,” make the garment they appear on “recognizable as a cheerleading uniform.” In other words, the district court found that the aesthetic features of a cheerleading uniform merged with the functional purpose of the cheerleading uniform. A Test in Five Parts On appeal, in a 2-1 decision in favor of Varsity, the Sixth Circuit overturned the district court’s ruling, finding that the designs were, in fact, protectable. In so finding, the Sixth Circuit laid out a multi-part test to determine whether the designs were protectable, asking: (1) Is the design a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work? (i.e., is it the type of work protected by the Copyright Act?); (2) If so, then is it a design of a useful article—“an article having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information”? (i.e., is the design useful?); (3) What are the utilitarian aspects of the useful article?; (4) Can the viewer of the design identify pictorial, graphic or sculptural features separate from the utilitarian aspects of the article?; and, if so, (5) Can “the pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features” of the design of the useful article exist independently of the utilitarian aspects of the useful article? The Sixth Circuit found that these first two factors were easily satisfied: the designs were two-dimensional works of art that had intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information. As to the third question—identifying the utilitarian aspects of the article—the Sixth Circuit found that cheerleading uniforms have an intrinsic utilitarian function, namely to “cover the body, wick away moisture, Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP pillsburylaw.com | 2 . Client Alert Intellectual Property and withstand the rigors of athletic movements.” Star argued that the designs’ “decorative function” was one of the utilitarian aspects of the uniform; the Sixth Circuit rejected this contention, stating, “[u]nder this theory of functionality, Mondrian’s painting would be unprotectable because the painting decorates the room in which it hangs.” It went on to state that “holding that the decorative function is a utilitarian aspect of an article would make all fabric designs, which serve no other function than to make a garment more attractive, ineligible for copyright protection. But it is well established that fabric designs are eligible for copyright protection.” Thus, the designs were not part of the utilitarian aspects of the clothing, and were therefore potentially subject to copyright protection. The final two questions of the Sixth Circuit’s analysis concerned the issue of separability—whether the utilitarian aspects of the design were separable from the utilitarian aspects of the design, or, in other words, whether the design of the clothing could be separated from the uniform’s function of covering the body, wicking away moisture and withstanding the rigors of athletic movements. The Sixth Circuit considered in depth how this issue should be approached, noting that there are two ways to determine whether a work is separable from the utilitarian aspects of an article—physical separability and conceptual separability. Physical separability means that the useful article contains pictorial, graphic or sculptural features that can be physically separated from the article by ordinary means while leaving the utilitarian aspects of the article completely intact. However, the Sixth Circuit noted that this test could lead to inconsistent results—for instance, if an artist made a statuette separately before putting a lamp fixture on top of it, then it would be copyrightable, but if the statuette were wired through the body with a lamp socket in the head, the statuette may not be eligible for copyright protection.

The Sixth Circuit also noted that few scholars or courts have relied on the physical-separability test, and that no court has relied on that test without also considering conceptual separability. Thus, the Sixth Circuit adopted the conceptualseparability test only, holding that “the Copyright Act protects the ‘pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features’ of a design of a useful article even if those features cannot be removed physically from the useful article, as long as they are conceptually separable from the utilitarian aspects of the article.” The Sixth Circuit went through the many approaches to conceptual separability in various Circuits,1 ultimately adopting a “hybrid approach” to determine whether an artistic design is conceptually separable from the utilitarian aspects of the article, proceeding to the fourth and fifth questions set forth above. On question four, the Sixth Circuit found that it could identify the graphic features of Varsity’s designs—the arrangement of stripes, chevrons, zigzags and color-blocking. The court wrote: “A plain white cheerleading top and plain white skirt still cover the body and permit the wearer to cheer, jump, kick, and flip” and, thus, the graphic design concepts—including the stripes, chevrons, colorblocks and zigzags—can be identified separately from the utilitarian aspects of the cheerleading uniform. On question five, the Sixth Circuit found that the stripes, chevrons, color blocks and zigzags on the uniforms could, in fact, “exist independently” of the utilitarian aspects of the cheerleading uniform.

This conclusion was supported by the evidence that Varsity’s designers could sketch their designs and arrange them on various items of clothing, showing that the designs were “transferable to articles other than the traditional cheerleading uniform.” Indeed, the Sixth Circuit wrote, “nothing (save perhaps good taste) prevents Varsity from printing or painting its designs, framing them, and hanging the resulting prints on the wall as art.” ï§ 1 See Varsity Brands, Inc. v. Star Athletica, LLC, 799 F.3d 468, 484 (6th Cir.

2015), for a full list of the tests applied by different courts in different Circuits. Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP pillsburylaw.com | 3 . Client Alert Intellectual Property Finding that all factors were met, and concluding that “the arrangement of stripes, chevrons, color blocks, and zigzags [were] wholly unnecessary to the performance of the garment’s ability to cover the body, permit free movement, and wick moisture,” the Sixth Circuit found that graphic features of the designs were subject to copyright protection. The Sixth Circuit then expanded on its decision, seeking to clarify which elements of clothing may be protected under the Copyright Act, writing: “The Copyright Act protects fabric designs, but not dress designs.” The Sixth Circuit wrote that a person could obtain a copyright for a sweater with a “squirrel design”—the sweater still functions without the design. However, the Sixth Circuit wrote, “the creative arrangement of sequins, beads, ribbon, and tulle, which form the bust, waistband of a dress, do not qualify for copyright protection because each of these elements (bust, waistband, and skirt) all serve to clothe the body.” A Call for “Supreme” Clarity In dissent, Judge McKeague argued that the majority had wrongly defined “function,” and, because of this misunderstanding, had incorrectly concluded that the designs of the cheer uniforms were conceptually separable from the utility of the uniforms. He urged a narrower approach to “function,” suggesting that the decorative elements of the cheer uniforms were functional in that they serve to identify the cheerleader. He wrote that “without stripes, braids, and chevrons, we are left with a blank white pleated skirt and crop top,” which “may be appropriate attire for a match at the All England Lawn Tennis Club, but not for a member of a cheerleading squad.” He stated that if clothing identifies its wearer as a member of a group, it should be deemed functional. On that premise, it follows that the stripes, braids and chevrons on the cheerleader uniform are not separable from the function of identifying cheerleaders. In closing, Judge McKeague called on the Supreme Court to provide clarity on a nationwide scale.

“It is apparent that either Congress or the Supreme Court (or both) must clarify copyright law with respect to garment design,” he wrote. “The law in this area is a mess—and it has been for a long time. The majority takes a stab at sorting it out, and so do I.

But until we get much-needed clarification, courts will continue to struggle and the business world will continue to be handicapped by the uncertainty of the law.” The Court has heeded Judge McKeague’s request and will hopefully provide clarity on this matter. The Court will hear argument in the case during its 2016-17 term. The Court’s decision may have significant implications for those in the apparel business.

If the Court adopts the Sixth Circuit’s narrower definition of functionality, clothing designers and manufacturers will have much broader protection for their designs than has traditionally been granted. However, this may also widen the universe of clothing designers, manufacturers and retailers’ exposure to liability for designs that are substantially similar to the designs of others. The Courts approach to separability too will affect the scope of protection granted to copyright.

This much needed clarification is fashionably late, but much needed for businesses to understand the extent to which their designs are protected, or are infringing on the designs of others. Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP pillsburylaw.com | 4 . Client Alert Intellectual Property If you have any questions about the content of this Alert, please contact the Pillsbury attorney with whom you regularly work, or the authors below. Lori Levine (bio) Los Angeles +1.213.488.7189 lori.levine@pillsburylaw.com Jeffrey D. Wexler (bio) Los Angeles +1.213.488.7129 jeffrey.wexler@pillsburylaw.com Bobby Ghajar (bio) Los Angeles +1.213.488.7551 bobby.ghajar@pillsburylaw.com Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP is a leading international law firm with 18 offices around the world and a particular focus on the energy & natural resources, financial services, real estate & construction, and technology sectors. Recognized by Financial Times as one of the most innovative law firms, Pillsbury and its lawyers are highly regarded for their forward-thinking approach, their enthusiasm for collaborating across disciplines and their unsurpassed commercial awareness. This publication is issued periodically to keep Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP clients and other interested parties informed of current legal developments that may affect or otherwise be of interest to them. The comments contained herein do not constitute legal opinion and should not be regarded as a substitute for legal advice. © 2016 Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP.

All Rights Reserved. Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP pillsburylaw.com | 5 . .

v. Star Athletica, LLC, that the stripes, chevrons, zigzags, and color blocks that appear on a cheerleading uniform are protectable under the copyright laws. Fashion designs have traditionally had very limited protection under U.S. copyright law, which protects “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.” For a work to be considered original, it must be independently created by its author, and possess at least some minimal degree of creativity.

Certainly, clothing designs fall within this ambit of protection. However, the reason why clothing designs have been afforded relatively little protection under copyright law is that copyright protection does not apply to items that serve a utilitarian function. For example, a white t-shirt cannot garner copyright protection because the t-shirt is a useful item with no separately artistic element.

The only way for the design of a garment to acquire copyright protection is if the design “can be identified separately from, and [is] capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.” What this means has been the subject of much confusion and debate. In Varsity Brands, Inc., plaintiff Varsity, a company in the business of designing and manufacturing athletic apparel, had received several copyright registrations for much of its “two-dimensional artwork” for many of its designs for cheerleading outfits. In its complaint, Varsity alleged five claims of copyright infringement against defendant Star for selling cheerleading uniforms that were alleged to be substantially similar to Varsity’s designs. In response, at summary judgment, Star claimed that Varsity did not have a valid copyright in its designs because: (1) Varsity’s designs are for useful articles and are therefore not copyrightable; and (2) the pictorial, graphic, or sculptural elements of Varsity’s designs were not physically or conceptually separable from the uniforms, making the designs ineligible for copyright protection. Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP pillsburylaw.com | 1 .

Client Alert Intellectual Property Two of Varsity’s copyrighted designs The U.S. District Court for the Western District of Tennessee granted summary judgment in favor of Star, concluding that Varsity’s designs were not copyrightable because the graphic elements of those designs were not separable from the utilitarian function of a cheerleading uniform, finding that the “colors, stripes, chevrons, and similar designs typically associated with sports in general, and cheerleading in particular,” make the garment they appear on “recognizable as a cheerleading uniform.” In other words, the district court found that the aesthetic features of a cheerleading uniform merged with the functional purpose of the cheerleading uniform. A Test in Five Parts On appeal, in a 2-1 decision in favor of Varsity, the Sixth Circuit overturned the district court’s ruling, finding that the designs were, in fact, protectable. In so finding, the Sixth Circuit laid out a multi-part test to determine whether the designs were protectable, asking: (1) Is the design a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work? (i.e., is it the type of work protected by the Copyright Act?); (2) If so, then is it a design of a useful article—“an article having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information”? (i.e., is the design useful?); (3) What are the utilitarian aspects of the useful article?; (4) Can the viewer of the design identify pictorial, graphic or sculptural features separate from the utilitarian aspects of the article?; and, if so, (5) Can “the pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features” of the design of the useful article exist independently of the utilitarian aspects of the useful article? The Sixth Circuit found that these first two factors were easily satisfied: the designs were two-dimensional works of art that had intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information. As to the third question—identifying the utilitarian aspects of the article—the Sixth Circuit found that cheerleading uniforms have an intrinsic utilitarian function, namely to “cover the body, wick away moisture, Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP pillsburylaw.com | 2 . Client Alert Intellectual Property and withstand the rigors of athletic movements.” Star argued that the designs’ “decorative function” was one of the utilitarian aspects of the uniform; the Sixth Circuit rejected this contention, stating, “[u]nder this theory of functionality, Mondrian’s painting would be unprotectable because the painting decorates the room in which it hangs.” It went on to state that “holding that the decorative function is a utilitarian aspect of an article would make all fabric designs, which serve no other function than to make a garment more attractive, ineligible for copyright protection. But it is well established that fabric designs are eligible for copyright protection.” Thus, the designs were not part of the utilitarian aspects of the clothing, and were therefore potentially subject to copyright protection. The final two questions of the Sixth Circuit’s analysis concerned the issue of separability—whether the utilitarian aspects of the design were separable from the utilitarian aspects of the design, or, in other words, whether the design of the clothing could be separated from the uniform’s function of covering the body, wicking away moisture and withstanding the rigors of athletic movements. The Sixth Circuit considered in depth how this issue should be approached, noting that there are two ways to determine whether a work is separable from the utilitarian aspects of an article—physical separability and conceptual separability. Physical separability means that the useful article contains pictorial, graphic or sculptural features that can be physically separated from the article by ordinary means while leaving the utilitarian aspects of the article completely intact. However, the Sixth Circuit noted that this test could lead to inconsistent results—for instance, if an artist made a statuette separately before putting a lamp fixture on top of it, then it would be copyrightable, but if the statuette were wired through the body with a lamp socket in the head, the statuette may not be eligible for copyright protection.

The Sixth Circuit also noted that few scholars or courts have relied on the physical-separability test, and that no court has relied on that test without also considering conceptual separability. Thus, the Sixth Circuit adopted the conceptualseparability test only, holding that “the Copyright Act protects the ‘pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features’ of a design of a useful article even if those features cannot be removed physically from the useful article, as long as they are conceptually separable from the utilitarian aspects of the article.” The Sixth Circuit went through the many approaches to conceptual separability in various Circuits,1 ultimately adopting a “hybrid approach” to determine whether an artistic design is conceptually separable from the utilitarian aspects of the article, proceeding to the fourth and fifth questions set forth above. On question four, the Sixth Circuit found that it could identify the graphic features of Varsity’s designs—the arrangement of stripes, chevrons, zigzags and color-blocking. The court wrote: “A plain white cheerleading top and plain white skirt still cover the body and permit the wearer to cheer, jump, kick, and flip” and, thus, the graphic design concepts—including the stripes, chevrons, colorblocks and zigzags—can be identified separately from the utilitarian aspects of the cheerleading uniform. On question five, the Sixth Circuit found that the stripes, chevrons, color blocks and zigzags on the uniforms could, in fact, “exist independently” of the utilitarian aspects of the cheerleading uniform.

This conclusion was supported by the evidence that Varsity’s designers could sketch their designs and arrange them on various items of clothing, showing that the designs were “transferable to articles other than the traditional cheerleading uniform.” Indeed, the Sixth Circuit wrote, “nothing (save perhaps good taste) prevents Varsity from printing or painting its designs, framing them, and hanging the resulting prints on the wall as art.” ï§ 1 See Varsity Brands, Inc. v. Star Athletica, LLC, 799 F.3d 468, 484 (6th Cir.

2015), for a full list of the tests applied by different courts in different Circuits. Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP pillsburylaw.com | 3 . Client Alert Intellectual Property Finding that all factors were met, and concluding that “the arrangement of stripes, chevrons, color blocks, and zigzags [were] wholly unnecessary to the performance of the garment’s ability to cover the body, permit free movement, and wick moisture,” the Sixth Circuit found that graphic features of the designs were subject to copyright protection. The Sixth Circuit then expanded on its decision, seeking to clarify which elements of clothing may be protected under the Copyright Act, writing: “The Copyright Act protects fabric designs, but not dress designs.” The Sixth Circuit wrote that a person could obtain a copyright for a sweater with a “squirrel design”—the sweater still functions without the design. However, the Sixth Circuit wrote, “the creative arrangement of sequins, beads, ribbon, and tulle, which form the bust, waistband of a dress, do not qualify for copyright protection because each of these elements (bust, waistband, and skirt) all serve to clothe the body.” A Call for “Supreme” Clarity In dissent, Judge McKeague argued that the majority had wrongly defined “function,” and, because of this misunderstanding, had incorrectly concluded that the designs of the cheer uniforms were conceptually separable from the utility of the uniforms. He urged a narrower approach to “function,” suggesting that the decorative elements of the cheer uniforms were functional in that they serve to identify the cheerleader. He wrote that “without stripes, braids, and chevrons, we are left with a blank white pleated skirt and crop top,” which “may be appropriate attire for a match at the All England Lawn Tennis Club, but not for a member of a cheerleading squad.” He stated that if clothing identifies its wearer as a member of a group, it should be deemed functional. On that premise, it follows that the stripes, braids and chevrons on the cheerleader uniform are not separable from the function of identifying cheerleaders. In closing, Judge McKeague called on the Supreme Court to provide clarity on a nationwide scale.

“It is apparent that either Congress or the Supreme Court (or both) must clarify copyright law with respect to garment design,” he wrote. “The law in this area is a mess—and it has been for a long time. The majority takes a stab at sorting it out, and so do I.

But until we get much-needed clarification, courts will continue to struggle and the business world will continue to be handicapped by the uncertainty of the law.” The Court has heeded Judge McKeague’s request and will hopefully provide clarity on this matter. The Court will hear argument in the case during its 2016-17 term. The Court’s decision may have significant implications for those in the apparel business.

If the Court adopts the Sixth Circuit’s narrower definition of functionality, clothing designers and manufacturers will have much broader protection for their designs than has traditionally been granted. However, this may also widen the universe of clothing designers, manufacturers and retailers’ exposure to liability for designs that are substantially similar to the designs of others. The Courts approach to separability too will affect the scope of protection granted to copyright.

This much needed clarification is fashionably late, but much needed for businesses to understand the extent to which their designs are protected, or are infringing on the designs of others. Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP pillsburylaw.com | 4 . Client Alert Intellectual Property If you have any questions about the content of this Alert, please contact the Pillsbury attorney with whom you regularly work, or the authors below. Lori Levine (bio) Los Angeles +1.213.488.7189 lori.levine@pillsburylaw.com Jeffrey D. Wexler (bio) Los Angeles +1.213.488.7129 jeffrey.wexler@pillsburylaw.com Bobby Ghajar (bio) Los Angeles +1.213.488.7551 bobby.ghajar@pillsburylaw.com Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP is a leading international law firm with 18 offices around the world and a particular focus on the energy & natural resources, financial services, real estate & construction, and technology sectors. Recognized by Financial Times as one of the most innovative law firms, Pillsbury and its lawyers are highly regarded for their forward-thinking approach, their enthusiasm for collaborating across disciplines and their unsurpassed commercial awareness. This publication is issued periodically to keep Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP clients and other interested parties informed of current legal developments that may affect or otherwise be of interest to them. The comments contained herein do not constitute legal opinion and should not be regarded as a substitute for legal advice. © 2016 Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP.

All Rights Reserved. Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP pillsburylaw.com | 5 . .