Revenue Recognition: The FASB's New Guidelines and Their Effect on Your Contracts with Customers

Moss Adams

Description

Certified Public Accountants | Business Consultants

J U LY 2 014

Revenue Recognition

The FASB’s New Guidelines and Their Effect on

Your Contracts with Customers

. MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 2

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

3

THE BA SIC PRINCIPLE

5

EFFECTI V E DATE S A ND TR A NSITION

7

Full Retrospective with Optional Practical Expedients

7

Modified Retrospective

8

How to Choose? Two Examples

8

A PPLY ING THE NE W GUIDELINE S

9

Step 1: Identify the Contract

9

Step 2: Identify the Separate Performance Obligations

11

Step 3: Calculate the Total Transaction Price

14

Step 4: Allocate the Transaction Price to the Performance Obligations

18

Step 5: Recognize the Revenue

19

OTHER IS SUE S

25

Contract Costs

25

Contract Modifications

26

Disclosures

27

. MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 3

Introduction

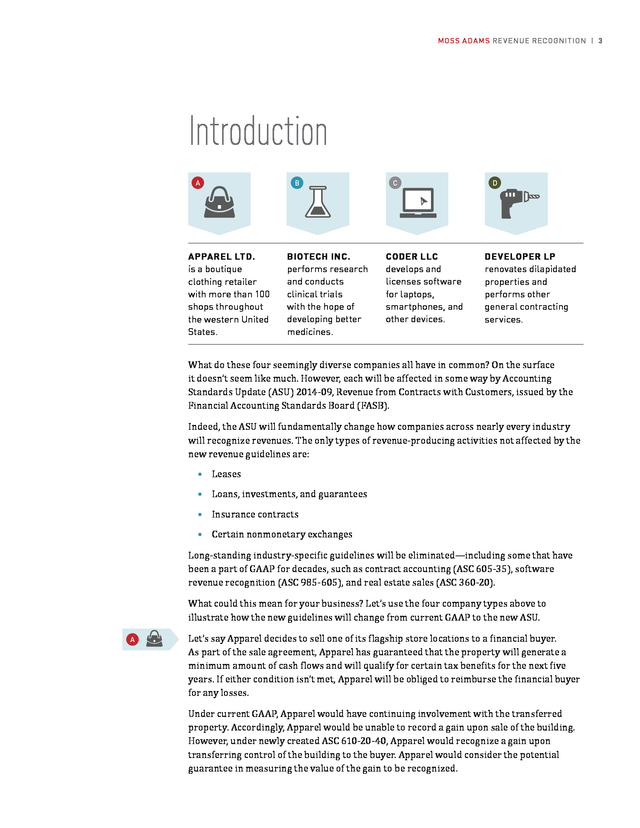

A

APPAREL LTD.

is a boutique

clothing retailer

with more than 100

shops throughout

the western United

States.

B

BIOTECH INC.

performs research

and conducts

clinical trials

with the hope of

developing better

medicines.

C

CODER LLC

develops and

licenses software

for laptops,

smartphones, and

other devices.

D

DEVELOPER LP

renovates dilapidated

properties and

performs other

general contracting

services.

What do these four seemingly diverse companies all have in common? On the surface

it doesn’t seem like much. However, each will be affected in some way by Accounting

Standards Update (ASU) 2014-09, Revenue from Contracts with Customers, issued by the

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB).

Indeed, the ASU will fundamentally change how companies across nearly every industry

will recognize revenues. The only types of revenue-producing activities not affected by the

new revenue guidelines are:

• Leases

• Loans, investments, and guarantees

• Insurance contracts

• Certain nonmonetary exchanges

Long-standing industry-specific guidelines will be eliminated—including some that have

been a part of GAAP for decades, such as contract accounting (ASC 605-35), software

revenue recognition (ASC 985-605), and real estate sales (ASC 360-20).

A

What could this mean for your business? Let’s use the four company types above to

illustrate how the new guidelines will change from current GAAP to the new ASU.

Let’s say Apparel decides to sell one of its flagship store locations to a financial buyer.

As part of the sale agreement, Apparel has guaranteed that the property will generate a

minimum amount of cash flows and will qualify for certain tax benefits for the next five

years. If either condition isn’t met, Apparel will be obliged to reimburse the financial buyer

for any losses.

Under current GAAP, Apparel would have continuing involvement with the transferred

property.

Accordingly, Apparel would be unable to record a gain upon sale of the building. However, under newly created ASC 610-20-40, Apparel would recognize a gain upon transferring control of the building to the buyer. Apparel would consider the potential guarantee in measuring the value of the gain to be recognized. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 4 B Let’s say Biotech performs research on a new drug compound on behalf of a customer. Biotech previously received a nonrefundable up-front payment and is entitled to a $25 million nonrefundable milestone payment upon the successful enrollment of 100 patients into a Phase III clinical trial. Although the activities necessary to complete Phase III enrollment are substantive, Biotech believes it is 70 percent likely to achieve the milestone. Under current GAAP, Biotech would likely recognize the up-front nonrefundable payment over the period it performs services, using a proportional performance methodology. Biotech could elect to recognize the milestone payment in its entirety when the milestone is achieved. C Under the new ASU, given the likelihood of achieving the milestone, Biotech would include the milestone payment as part of the “transaction price.” Accordingly, as Biotech performs services, it would recognize revenue for both the up-front and milestone portions of the transaction price—even prior to actually achieving the milestone. Let’s say Coder delivers a license for version 11.0 of its enterprise risk management software, together with one year of 24x7 telephone support. There’s no vendor-specific objective evidence (VSOE) of the fair value of the telephone support. Under current GAAP, the entire license fee is deferred and recognized as revenue over the one-year support period. D Under the new ASU, a portion of the arrangement fee likely would be recognized as revenue upon delivery of the license. The balance would be recognized as revenue ratably over the period telephone support is provided. And finally, let’s say Developer is building 10 apartment units overlooking a tropical beach. Each unit is under contract, and Developer may not transfer a unit to another party.

Buyers of the units (the customers in this example) will make progress payments to Developer during the construction period. If a buyer defaults, Developer may elect to complete the construction of the unit and obtain an enforceable legal right for full payment from the defaulting buyer. Under current GAAP, each of the units is a separate profit center. Developer would likely recognize revenue once all work for a given unit is completed and the unit is legally transferred to the buyer at closing. But under the new ASU, each unit would represent a separate customer contract.

Developer would likely recognize revenue as progress toward completing each unit is made, based on input measures such as labor hours or costs incurred. These are just a few examples across just a handful of industries. However, the ASU will have a broad impact on most every company. This is especially true for entities that sell bundled product and service offerings, provide return or refund rights, or occasionally amend contract terms. In this guide we’ll examine the basic principle behind the new guidelines, discuss the transition process, and then delve into the major changes the ASU brings about—providing examples along the way to help guide your understanding. .

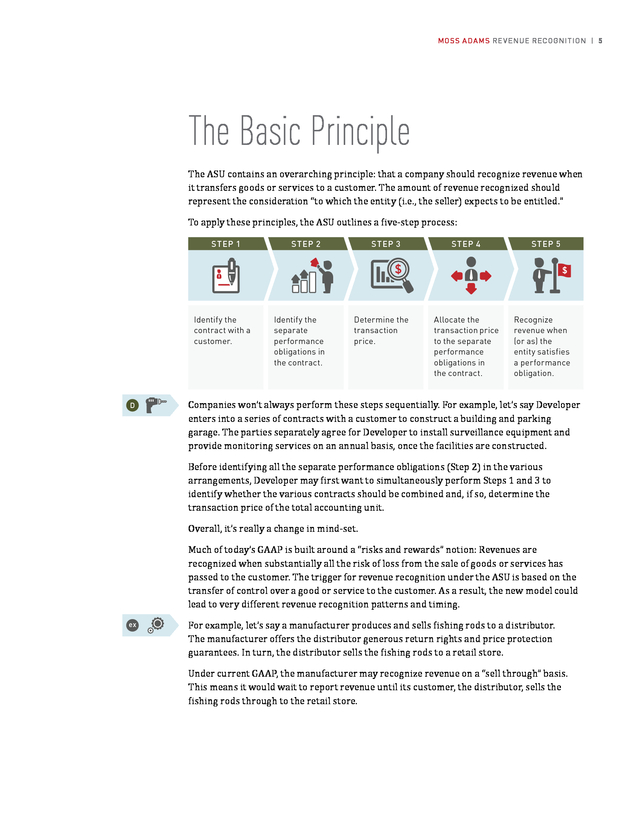

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 5 The Basic Principle The ASU contains an overarching principle: that a company should recognize revenue when it transfers goods or services to a customer. The amount of revenue recognized should represent the consideration “to which the entity (i.e., the seller) expects to be entitled.” To apply these principles, the ASU outlines a five-step process: STEP 1 Identify the contract with a customer. D STEP 2 Identify the separate performance obligations in the contract. STEP 3 Determine the transaction price. STEP 4 Allocate the transaction price to the separate performance obligations in the contract. STEP 5 Recognize revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation. Companies won’t always perform these steps sequentially. For example, let’s say Developer enters into a series of contracts with a customer to construct a building and parking garage. The parties separately agree for Developer to install surveillance equipment and provide monitoring services on an annual basis, once the facilities are constructed. Before identifying all the separate performance obligations (Step 2) in the various arrangements, Developer may first want to simultaneously perform Steps 1 and 3 to identify whether the various contracts should be combined and, if so, determine the transaction price of the total accounting unit. Overall, it’s really a change in mind-set. ex Much of today’s GAAP is built around a “risks and rewards” notion: Revenues are recognized when substantially all the risk of loss from the sale of goods or services has passed to the customer.

The trigger for revenue recognition under the ASU is based on the transfer of control over a good or service to the customer. As a result, the new model could lead to very different revenue recognition patterns and timing. For example, let’s say a manufacturer produces and sells fishing rods to a distributor. The manufacturer offers the distributor generous return rights and price protection guarantees. In turn, the distributor sells the fishing rods to a retail store. Under current GAAP, the manufacturer may recognize revenue on a “sell through” basis. This means it would wait to report revenue until its customer, the distributor, sells the fishing rods through to the retail store. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 6 The manufacturer may have selected this accounting policy because it retained a number of risks following delivery of the products to the distributor. Specifically, the arrangement fee may not be fixed or determinable—a necessary condition for recognizing revenue under today’s accounting rules—because of the generous return rights and price protection guarantees included in the contract. Under the ASU, the manufacturer will likely recognize revenue upon delivery of the fishing rods to the distributor. This is because control over those products has transferred to the distributor at that time. The manufacturer would consider the risks of price concessions and future returns when determining the transaction price in Step 3 of the process—that is, in calculating how much revenue to recognize at the time of transfer. In some circumstances the new five-step process may result in the same accounting outcome as current GAAP, but the logic and reasoning for reaching those conclusions may change. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 7 Effective Dates and Transition PUBLIC ENTITIE S For annual reporting periods beginning on or after December 15, 2016, and related interim periods NONPUBLIC ENTITIE S For annual reporting periods beginning on or after December 15, 2017, and interim periods beginning after December 15, 2018 The ASU defines a public entity as any one of the following: • A public business entity, as described in ASU 2013-12 • A not-for-profit entity that has issued, or is a conduit bond obligor for, securities that are traded, listed, or quoted on an exchange or an over-the-counter market • An employee benefit plan that files or furnishes financial statements to the SEC For example, for a public, calendar-year-end company, the ASU would first be applied in the Form 10-Q for the quarter ending March 31, 2017. There is no relief for smaller reporting companies or nonaccelerated filers. Early adoption of the new standard isn’t permitted for public entities. For all others (nonpublic entities), early adoption is allowed, but no earlier than the effective date for public entities. There are two methods companies may choose from to transition to the new standard: Full Retrospective with Optional Practical Expedients All prior periods presented in the financial statements would be presented as though the new guidelines had always been in effect, with the optional use of one or more of the following practical expedients: • Entities would not need to restate completed contracts that began and ended within the same annual reporting period. • For completed contracts that have variable consideration, entities may restate prior periods using the final transaction price rather than estimating the transaction price that would have been used throughout comparative reporting periods. • Entities would not need to disclose the amount of transaction price allocated to remaining performance obligations and an explanation of when the entity expects to recognize that amount as revenue for periods presented before the date of initial application. Note that for SEC registrants it’s uncertain whether the fourth and fifth years of the selected financial data table would also require restatement. Current SEC rules would technically require such periods to be recast.

However, the SEC may offer some type of relief, similar to what has been done in previous circumstances in which new accounting standards have required retrospective adoption. The SEC hopefully will provide clarity on this matter shortly. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 8 Modified Retrospective Entities would apply the new ASU only to contracts that are outstanding as of the date of adoption (e.g., January 1, 2017, for public, calendar-year-end companies). This would involve comparing how those contracts would have been reported under the ASU with how they were actually booked under existing GAAP. Any necessary adjustments would be recorded to opening retained earnings on the date of adoption—prior periods would not be restated. If companies elect this method of transition, they’ll need to disclose the effect of adopting the new standard on each affected financial statement line item. In other words, in the initial period of adoption, the actual financial statements would reflect the application of the ASU.

However, the footnotes would show pro forma balances had existing GAAP continued to be applied. Significant variances would require explanation. These disclosures would require entities to effectively keep two sets of books during the initial year of applying the new ASU. How to Choose? Two Examples C The selection of a transition method is very important because it can affect reported trends, perhaps in surprising ways.

For example, let’s say that on December 31, 2016, Coder sells a license to software that allows for four-dimensional mapping. Coder makes no commitments, express or implied, to update the software following delivery of the license. However, Coder does agree to provide telephone or e-mail support for the next three years. The support is intended to help the customer maximize the utility of the software—for instance, by providing tips on how to take advantage of some of its embedded functionality. Coder sells the bundled software and support solution for $20 million. There’s no VSOE for the support.

Therefore, the entire $20 million fee would be spread over the three-year support period under current GAAP. Under the new ASU, the support services would be separated from the software license. Assume that $14 million of the arrangement fee were allocated to the license. The ASU would require the entire license fee to be recognized as revenue upon transferring the license to the customer, which occurred on December 31, 2016. Coder has a calendar year-end and adopts the new ASU on January 1, 2017. If Coder uses a modified retrospective transition approach, $14 million of revenue would in essence “disappear”: • Upon adoption of the ASU, Coder would eliminate $14 million of deferred revenue reported under current GAAP from the balance sheet and would adjust opening retained earnings by the same amount.

This adjustment reflects that the license portion of the arrangement fee would have been booked as revenue in 2016 had the ASU been applied in that period. • When a modified retrospective transition method is used, prior-period results are not restated. Accordingly, the $14 million in revenue wouldn’t appear in either the 2016 or 2017 published income statements. It just disappears. Companies should decide on which transition method to select as soon as possible.

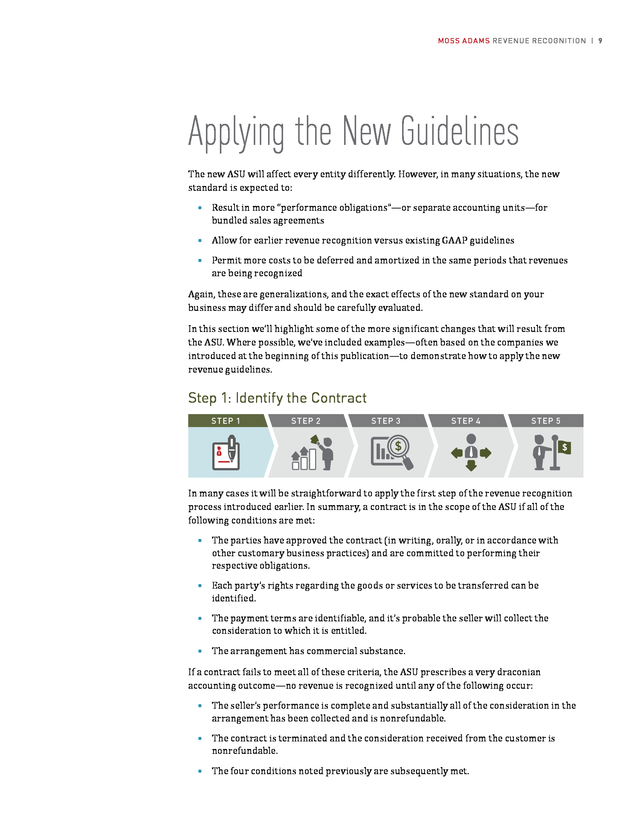

This will help identify the extent of data gathering required to properly adopt the ASU and inform the nature and timing of systems and process changes. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 9 Applying the New Guidelines The new ASU will affect every entity differently. However, in many situations, the new standard is expected to: • Result in more “performance obligations”—or separate accounting units—for bundled sales agreements • Allow for earlier revenue recognition versus existing GAAP guidelines • Permit more costs to be deferred and amortized in the same periods that revenues are being recognized Again, these are generalizations, and the exact effects of the new standard on your business may differ and should be carefully evaluated. In this section we’ll highlight some of the more significant changes that will result from the ASU. Where possible, we’ve included examples—often based on the companies we introduced at the beginning of this publication—to demonstrate how to apply the new revenue guidelines. Step 1: Identify the Contract STEP 1 STEP 2 STEP 3 STEP 4 STEP 5 In many cases it will be straightforward to apply the first step of the revenue recognition process introduced earlier. In summary, a contract is in the scope of the ASU if all of the following conditions are met: • The parties have approved the contract (in writing, orally, or in accordance with other customary business practices) and are committed to performing their respective obligations. • Each party’s rights regarding the goods or services to be transferred can be identified. • The payment terms are identifiable, and it’s probable the seller will collect the consideration to which it is entitled. • The arrangement has commercial substance. If a contract fails to meet all of these criteria, the ASU prescribes a very draconian accounting outcome—no revenue is recognized until any of the following occur: • The seller’s performance is complete and substantially all of the consideration in the arrangement has been collected and is nonrefundable. • The contract is terminated and the consideration received from the customer is nonrefundable. • The four conditions noted previously are subsequently met. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 10 DID YOU K NOW? One way that a contract with a customer may not exist is if there are doubts around collectibility. Specifically, a company can’t have a contract with a customer unless it’s probable that it will collect the amounts to which it will be entitled under the contract. This is the same threshold used today, under ASC 985-605-253(d), for companies that license software. However, under current GAAP, businesses that aren’t software companies typically can’t recognize revenues unless collectibility of amounts due under a contract B is reasonably assured. Although some practitioners interpret “reasonably assured” as a higher level of confidence than probable, the FASB did not.

The ASU’s basis for conclusions indicates that “the FASB understood that in practice, probable and reasonably assured had similar meanings.” As a result, the FASB doesn’t expect entities to change existing practices or arrive at different conclusions when evaluating collectibility using the “probable” threshold in the ASU versus current GAAP. The ASU applies only to contracts between a seller and a customer. A customer represents a party that will obtain goods or services in exchange for consideration. In certain types of arrangements, it may take some analysis to determine whether an entity has entered into a contract with a customer. For example, assume Biotech enters into a collaboration agreement with another pharmaceutical company.

In accounting for this arrangement, Biotech would first evaluate whether the other pharmaceutical company is a customer. This would be the case if the arrangement calls for both: • Biotech to provide goods or services to the counterparty, including licenses to certain intellectual property rights or research and development services • The counterparty to pay consideration in exchange for those goods and services, which may include potential variable or contingent amounts, including milestone payments and royalties However, sometimes a collaboration agreement may be more akin to a partnership rather than a contract with a customer. To demonstrate, assume Biotech and another party agree to copromote a developed product and share in any profits.

As part of the arrangement, the other party agrees to make payments to cover some of Biotech’s marketing expenses. Despite these payments, the collaboration partner isn’t a customer—the counterparty isn’t receiving goods or services in exchange for the payments. Hence this type of arrangement is outside the scope of the new revenue guidance. C In other cases certain transactions that weren’t revenue arrangements under current GAAP might now be under the ASU. For example, let’s say Coder enters into a funded software-development arrangement with a customer.

Assuming technological feasibility was established prior to entering into the arrangement, paragraphs 86-87 of ASC 985-60525 currently require that any payments received under this type of arrangement be netted against capitalized development costs rather than reported as revenues. Under the ASU, this arrangement would be considered a contract with a customer. Therefore, Coder would record revenues for any goods and services transferred to the customer rather than reducing capitalized development costs as required by current GAAP. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 11 Step 2: Identify the Separate Performance Obligations STEP 1 STEP 2 STEP 3 STEP 4 STEP 5 Companies commonly sell multiple products and services in a single transaction. From an accounting perspective, a key issue is whether individual goods and services in the bundled arrangement can be accounted for separately, with a portion of the total arrangement fee recognized as revenue each time a product or service is delivered, or all of the revenue in the arrangement must be deferred and recognized only once the final good or service in the contract is delivered. C D A B Existing GAAP describes when certain individual elements in an arrangement can be “unbundled,” allowing for revenue recognition upon delivery of each product or service. The rules differ by industry, though. For instance, software companies can unbundle an arrangement when there is VSOE of the fair value of the undelivered elements. This means that the licensor has strong evidence of the price at which it sells any remaining products or services, such as postcontract support (PCS), on a stand-alone basis—in other words, unencumbered by the initial software license or any other deliverables. Contractors may be able to segment a customer contract into smaller “profit centers” if certain conditions are met. For example, a contractor may submit a bundled proposal to deliver a manufacturing plant, an office building, and a parking garage in three phases, all on a single parcel of land.

Depending on facts and circumstances, the contractor may be able to account for the plant, building, and garage portions of the contract separately, with different margins assigned to each contract segment. Other companies, such as those in the biotechnology or retail industries, can unbundle a multiple-element arrangement if the conditions in ASC 605-25-25 are met (the most important of which is that any delivered items have stand-alone value to the customer). The ASU replaces all of these various guidelines with a single principle. It states that a seller should identify any performance obligations within a contract, then allocate a portion of the total contract price to each distinct performance obligation. Once the company satisfies a particular performance obligation, the value assigned to it should be recognized as revenue. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 12 A performance obligation represents a distinct product or service within a broader contract that the seller has promised to deliver to the customer. The ASU indicates that a product or service is distinct if both of the following criteria are met: • The promised good or service is capable of being distinct because the customer can benefit from it either on its own or together with other resources that are readily available to the customer. • The promised good or service is distinct within the context of the contract. For example, the good or service: »» Isn’t being used as an input to produce a combined output specified by the customer »» Doesn’t significantly modify or customize another good or service in the contract D »» Isn’t highly dependent on, or highly interrelated with, other promised goods or services in the contract For example, assume Developer agrees to rebuild a dilapidated warehouse for a customer. The construction process will involve a number of steps, including demolishing the existing structure, pouring the foundation, framing, installing plumbing lines and electrical fixtures, insulating the walls, installing drywall, and performing finish work. Each of these activities is “capable of being distinct.” For instance, the customer can benefit from the demolition even if Developer performs nothing else. (Presumably the customer could find someone else to complete the rest of the work if it desired.) Similarly, the customer would obtain value from Developer’s framing services or its drywall installation. Even if the remainder of construction hypothetically was turned over to another contractor to complete, no rework would be required for the framing services or drywall installation delivered by Developer. However, the various goods and services aren’t distinct within the context of the entire contract.

Each one represents an input to produce a combined output specified by the customer—a rebuilt warehouse. Because the various aspects of the contract are interrelated, Developer wouldn’t have distinct performance obligations for each step of construction process. That is, the second criterion mentioned in the ASU isn’t met for each of these activities, since they’re not distinct within the context of the contract with the customer. Therefore, Developer would conclude that there’s just one performance obligation in the arrangement—delivery of a rebuilt warehouse. However, as we’ll see in Step 5, the fact that the arrangement contains just one distinct performance obligation doesn’t mean that all revenue will be deferred until the new warehouse is completed. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 13 B Let’s look at another example. Assume Biotech enters into a collaboration agreement with a customer. Under the terms of the agreement, Biotech delivers a license that will allow the customer exclusive marketing and distribution rights to a drug candidate currently under development. Biotech also agrees to perform R&D services with the goal of achieving approval of the drug candidate. In exchange the customer agrees to pay Biotech an up-front, nonrefundable license fee.

The customer also agrees to make a large milestone payment if the drug candidate is approved by regulators as well as pay royalties on future sales of the commercialized product. Depending on facts and circumstances, Biotech may have two performance obligations in this arrangement—providing a license to its intellectual property and performing R&D services. Alternatively, Biotech may just have a single performance obligation. How so? If the R&D services could be performed by others, such as contract research organizations or the customer itself, then delivery of the license and R&D services would likely be considered distinct performance obligations. This is because the customer could benefit from the license without Biotech providing the R&D services.

The two performance obligations aren’t interdependent. C On the other hand, in circumstances where the underlying drug compound is unique (or perhaps is in a very early stage of development), the customer probably couldn’t benefit from the license on its own. The license would likely have value to the customer only together with R&D services that only Biotech has the capability of providing. Hence, the R&D services would be highly interrelated with the license.

The two activities wouldn’t be considered distinct, and the arrangement would have just one accounting unit. Let’s look at a third example: Coder licenses software to a customer and agrees to provide PCS for one year. However, upon closer examination of the customer contract, Coder determines that the PCS includes both 24x7 telephone support and delivery of software updates for bug fixes and functionality improvements, when and if these are made available. Under current GAAP, all types of PCS are typically viewed as a single accounting unit. However, Coder will likely reach a different conclusion under the ASU—that the telephone support and the unspecified upgrade rights represent distinct performance obligations. The unspecified product upgrades may be based on the software developer’s internal product road map or discussions with customers about feature enhancements. In contrast, the telephone support is geared primarily toward helping address user issues related to the current software. Therefore, the two services are each capable of being distinct.

In addition, they’re not interrelated to, or interdependent on, one another in the context of the contract. So, in summary, the arrangement may contain up to three distinct performance obligations: delivery of a software license, telephone support, and unspecified updates. Note , however, that specified upgrades—in which a seller agrees to make certain software updates—will also typically qualify as distinct performance obligations under the ASU. Unlike current GAAP, though, specified upgrade rights won’t preclude revenue recognition for other distinct performance obligations in a customer contract, even if there’s no VSOE for the fair value of those specified upgrades. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 14 Step 3: Calculate the Total Transaction Price STEP 1 STEP 2 STEP 3 STEP 4 STEP 5 This step can be challenging to apply, even for fixed-price arrangements. This is because the ASU requires companies to consider potential discounts, concessions, rights of return, liquidated damages, performance bonuses, and other forms of variable consideration when calculating the transaction price. Here are some industry-specific examples of variable consideration: Industry Examples of Variable Consideration Retail • If customers purchase $1,000 or more of goods, they’ll receive a 10% discount. • If customers aren’t completely satisfied with their purchase, they can return it for a full refund within 30 days. Life sciences • Upon enrollment of the first patient in a Phase II clinical trial, an entity will receive a $50 million milestone payment. • The owner of intellectual property (IP) will receive royalties of 5% on all sales of product containing that IP. Construction • If project completion is delayed beyond 180 days, the contractor will pay liquidated damages of $1,000 for every day delayed. • If a project is completed prior to year-end, the contractor will receive a performance bonus of $1 million. Software • A developer will grant concessions to the customer if the software doesn’t perform as expected. • A cloud provider agrees to deliver a free month of service if a customer signs up for a 12-month noncancelable contract. When estimating the amount of variable consideration to include in the transaction price, companies shouldn’t look just to the stated terms of the customer contract. Consideration should also be given to any past business practices of providing refunds or concessions or the intentions of the seller in potentially providing rebates or other credits to specific customers. D Variable consideration should be calculated using either a best estimate or expected value approach, whichever method is expected to better predict the amount of consideration to which an entity will be entitled. For example, assume Developer agrees to refurbish an office building.

The fixed price is $10 million. If the building receives a LEED Gold Certification, Developer will receive a $500,000 performance bonus. Developer believes it’s 60 percent likely that it will receive the certification. .

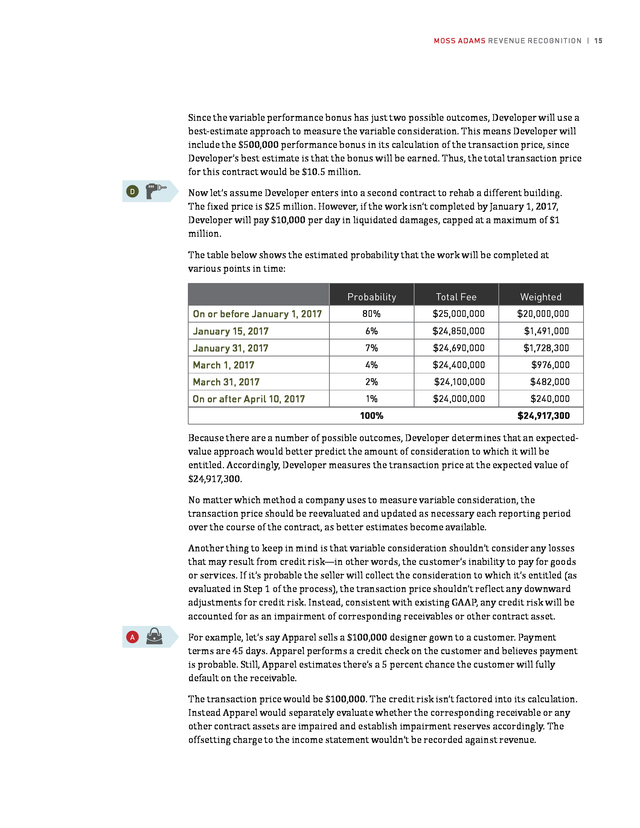

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 15 D Since the variable performance bonus has just two possible outcomes, Developer will use a best-estimate approach to measure the variable consideration. This means Developer will include the $500,000 performance bonus in its calculation of the transaction price, since Developer’s best estimate is that the bonus will be earned. Thus, the total transaction price for this contract would be $10.5 million. Now let’s assume Developer enters into a second contract to rehab a different building. The fixed price is $25 million. However, if the work isn’t completed by January 1, 2017, Developer will pay $10,000 per day in liquidated damages, capped at a maximum of $1 million. The table below shows the estimated probability that the work will be completed at various points in time: Probability Total Fee Weighted On or before January 1, 2017 80% $25,000,000 $20,000,000 January 15, 2017 6% $24,850,000 $1,491,000 January 31, 2017 7% $24,690,000 $1,728,300 March 1, 2017 4% $24,400,000 $976,000 March 31, 2017 2% $24,100,000 $482,000 On or after April 10, 2017 1% $24,000,000 $240,000 100% $24,917,300 Because there are a number of possible outcomes, Developer determines that an expectedvalue approach would better predict the amount of consideration to which it will be entitled.

Accordingly, Developer measures the transaction price at the expected value of $24,917,300. No matter which method a company uses to measure variable consideration, the transaction price should be reevaluated and updated as necessary each reporting period over the course of the contract, as better estimates become available. A Another thing to keep in mind is that variable consideration shouldn’t consider any losses that may result from credit risk—in other words, the customer’s inability to pay for goods or services. If it’s probable the seller will collect the consideration to which it’s entitled (as evaluated in Step 1 of the process), the transaction price shouldn’t reflect any downward adjustments for credit risk. Instead, consistent with existing GAAP, any credit risk will be accounted for as an impairment of corresponding receivables or other contract asset. For example, let’s say Apparel sells a $100,000 designer gown to a customer.

Payment terms are 45 days. Apparel performs a credit check on the customer and believes payment is probable. Still, Apparel estimates there’s a 5 percent chance the customer will fully default on the receivable. The transaction price would be $100,000.

The credit risk isn’t factored into its calculation. Instead Apparel would separately evaluate whether the corresponding receivable or any other contract assets are impaired and establish impairment reserves accordingly. The offsetting charge to the income statement wouldn’t be recorded against revenue. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 16 CONS TR A INT ON VA RI A BLE CONSIDER ATION When developing the ASU, the FASB acknowledged that there can be significant uncertainty involved in estimating variable consideration. In fact, it might even be misleading to reflect certain types of variable consideration in the transaction price. For this reason, the FASB introduced the concept of constraint. Specifically, variable consideration should ultimately be included in the transaction price only to the extent that it’s probable that a significant revenue reversal won’t occur. To be clear, the ASU requires a company to first estimate the total amount of variable consideration from a contract. Then, as a second independent step, a company will evaluate how much of the total estimated variable consideration should ultimately be included in the transaction price, considering the aforementioned constraint. B The ASU provides specific guidance for sales- or use-based royalties on licenses of IP. Specifically, in no circumstances should the transaction price include estimates of royalties on licenses of IP until any uncertainty around such royalties has been resolved.

In other words, royalties from licensing IP represent a type of variable consideration that must always be constrained. For example, assume Biotech grants a license to a customer to commercialize a developmental drug candidate. Biotech will also perform R&D services for the customer, with the goal of gaining regulatory approval. Biotech receives an up-front, nonrefundable license fee of $10 million. Biotech will also receive a milestone payment of $20 million upon regulatory approval and will be paid a 3 percent royalty on net sales of any commercialized products sold by the customer. In this contract the milestone payment and sales royalties represent variable consideration.

The milestone payment may or may not be included in the transaction price. Biotech would have to assess whether it’s probable that a significant revenue reversal won’t occur if the milestone payment were included in the transaction price. This determination will involve judgment and consideration of specific facts and circumstances. For example, if the contract were signed before the drug candidate even started Phase II clinical trials, this variable consideration likely would be constrained. On the other hand, if the contract were signed after completion of Phase III(b) trials, it’s less likely the variable consideration would be constrained. The sales royalties wouldn’t be included in the transaction price based on the ASU’s specific guidance around sales- or use-based royalties on licenses of IP.

Instead any sales royalties would be reported as revenues only as and when sales of the approved and commercialized product occur. Note that the ASU doesn’t define the term significant revenue reversal. It’s possible that the FASB may provide further interpretative guidance in the future to help clarify its intent around this term. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 17 SIGNIFICA NT FIN A NCING COMP ONENT The transaction price should be adjusted if the arrangement contains an implicit element of financing. To demonstrate, assume a manufacturing company typically sells a machine for $1 million, with 10-day payment terms. In one instance, though, the company enters into a contract to sell an identical machine for $1.11 million. Payment is due from the customer in one year’s time. In this circumstance there’s an implicit financing component to the arrangement.

The “cash price”—the cost of the equipment with normal 10-day payment terms—is $1 million. The transaction price in this arrangement is $1.11 million, or 11 percent higher than normal. This is because the manufacturing company in substance has provided the customer with a one-year loan in addition to providing equipment. When a customer contract contains a significant financing component, a company is required to adjust the transaction price to give consideration to the time value of money. Using the previous example, the transaction price would be $1 million, assuming that an 11 percent rate of interest is the prevailing market rate considering the customer’s credit standing. The manufacturing company would recognize $1 million of revenue when the equipment is transferred to the customer. Over the one-year “loan period,” the manufacturing company would accrue interest on the receivable.

Note that the ASU doesn’t allow the interest income to be reported as revenue. Instead it would typically be presented in the financing section of the income statement. As a practical expedient, a company can presume there’s no significant financing component in a customer contract if the time period between payment and performance of services, or delivery of products, is one year or less. B The ASU emphasizes that not all differences in the timing between satisfying a performance obligation and receiving payment give rise to a significant financing component. For example, assume Biotech agrees to perform R&D services for a customer— namely, conducting clinical trials on a new drug candidate.

Biotech owns the IP for this drug candidate but has exclusively licensed its marketing rights to the customer. As consideration, Biotech will receive a $10 million milestone payment, but only if the drug is approved by regulators. Regulatory approval won’t occur until three years from contract signing at the earliest. The delay between payment of the arrangement consideration and the performance of R&D services doesn’t give rise to a significant financing element. Designed to protect a customer from taking undue risk, milestone payments are customary in the life sciences industry.

In this example, there’s significant uncertainty as to whether Biotech will be able to develop a safe and effective medicine that will gain regulatory approval. The customer is delaying payment because of that uncertainty and not because Biotech is providing implicit financing. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 18 D Another example may be useful here. Let’s say Developer agrees to refurbish a 500,000-square-foot facility for a customer. The project is expected to take 18–24 months to complete. As is customary for similar types of contracts, Developer receives a 25 percent down payment, which will be used to acquire materials for the facility that are in limited supply.

The materials likely won’t be installed, however, until toward the end of the contract. The advance payment doesn’t give rise to a significant financing component. The payment is necessary to secure materials that are in scarce supply and likely have a long lead time to procure. This conclusion is appropriate even if the materials won’t be installed or delivered to the job site until the latter stages of the contract. Let’s also assume that three additional payments are due following specific milestones (upon passing the electrical inspection, completion of drywall installation, and receipt of the certificate of occupancy).

At each payment date the customer will withhold 5 percent of the amount due as retention. The retained amounts will be remitted to Developer only once the customer has signed off on all open punch-list items. Again, the retention isn’t designed to be a significant financing element. Instead it provides the customer with assurance that Developer will complete its obligations.

Accordingly, the retention provisions of the contract aren’t deemed to be a significant financing component. Step 4: Allocate the Transaction Price to the Performance Obligations STEP 1 STEP 2 STEP 3 STEP 4 STEP 5 The process for allocating the transaction price to the distinct performance obligations is similar to what’s done today in many industries and is based on a relative stand-alone selling-price approach. To perform the allocation, the business should first try to determine the stand-alone selling price of each performance obligation. This can be straightforward if the business routinely sells the product or service on a stand-alone basis to similar customers. If an entity doesn’t sell a particular performance obligation on a stand-alone basis, it will have to estimate the stand-alone selling price.

Techniques to make such estimates include: • Top-down approach. A company can work with its sales team to develop a price it believes the market would be willing to pay for its goods or services. In doing so, the company should consider its standing in the marketplace—for example, is it the market leader, meaning it could command a premium price? Or is it a new entrant, in which case it may have to discount its prices? • Bottom-up approach.

A company can also estimate the stand-alone selling price for a good or service based on a “cost plus” methodology, estimating its costs to provide a good or service and adding a reasonable margin for its production and selling efforts. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 19 In estimating the stand-alone selling price, the entity should maximize the use of observable inputs when available—for example, the published prices at which competitors sell similar goods and services. Of course, these prices may have to be adjusted to give consideration to customary discounts off list price that are provided to customers and any differences between the entity and its competitors. C If the stand-alone selling prices of one or more performance obligations are highly variable or uncertain, a business can use a residual approach so long as doing so is consistent with the objective of the ASU. That is, the amount allocated as a result of applying the residual approach would reflect the consideration to which a company expects to be entitled in exchange for a good or service. For example, assume Coder enters into a fixed-price bundled contract to deliver software licenses, implementation services, and one year of telephone support. Coder believes it can directly determine the stand-alone selling price of the telephone support based on substantive renewal rates.

Furthermore, although there’s no observable stand-alone selling price for the software license, Coder believes it can estimate this price using top-down and bottom-up approaches. The implementation services don’t constitute significant customization or modification of the software. Instead they involve Coder helping the customer troubleshoot any installation and interfacing issues that arise. There haven’t been many clients who have contracted for these services, and the prices in those instances have deviated substantially. Therefore, Coder’s pricing for the implementation services is highly variable. Under the ASU, Coder would be permitted to use a residual approach to allocate the total transaction price to the support services, provided that the outputs of this approach reflect the consideration that Coder would expect to be entitled in exchange for the service. However, before using a residual approach, Coder would evaluate whether there’s a discount embedded in the arrangement and whether that discount relates to one or both of the performance obligations whose stand-alone selling price can be determined—in this example, the telephone support or software license.

If so, then the discount would first have to be allocated to the license, the telephone support, or both before the residual amount would be allocated to the support services. Otherwise the discount would be allocated on a pro rata basis, after applying the residual approach, to all three performance obligations. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 20 Step 5: Recognize the Revenue STEP 1 STEP 2 STEP 3 STEP 4 STEP 5 Under the ASU, a company will recognize revenues as it satisfies a performance obligation. Said another way, revenue is recognized each time a company transfers a good or service to the customer and the customer obtains control over the delivered item. These principles seem straightforward, but they may result in very different patterns of revenue recognition compared with current GAAP. For example, let’s say a manufacturer enters into a contract with a customer to provide equipment and spare parts. The customer inspects, accepts, and pays for the equipment and spare parts but requests that the spare parts be stored at the manufacturer’s warehouse, segregated from the rest of the manufacturer’s salable inventory. In this case the manufacturer doesn’t have the right to use the spare parts or direct them to another entity—title to the parts transferred to the customer. The spare parts are available for delivery to the customer upon request, but the customer doesn’t expect to need the parts for another two to four years. This transaction represents a bill-and-hold sale.

Under current GAAP (SAB Topic 13), the manufacturer wouldn’t recognize revenues from the sale of the spare parts until the units were physically delivered to the customer—because, among other reasons, there’s no fixed delivery schedule. However, under the ASU the manufacturer would be able to recognize revenues from the sale of the spare parts. This is because the manufacturer has transferred control of those items to the customer.

The manufacturer no longer has title to the goods and can’t use them to satisfy other orders. The manufacturer has three performance obligations in this arrangement: • The sale of equipment • The sale of spare parts • Custodial services for the spare parts The total transaction price would be allocated to these three performance obligations. Revenues from the sale of equipment and spare parts would be recognized when the manufacturer transfers control of these items to the customer. As we’ll discuss in more detail later, the custodial services are performed over time. Accordingly, revenues would be recognized for this performance obligation over time. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 21 REFUND RIGHT S Often a company will sell items with an express or implied refund right. For example, the company will permit the customer to return a good for a full refund (or credit against a future purchase) if the customer isn’t satisfied with a purchase for any reason. When a good or service is sold together with a refund right, a company should record: • Revenue for the transferred goods or services in the amount of consideration to which the company expects to be entitled—therefore, no revenue would be recognized for products expected to be returned or services expected to be refunded • A refund liability for any consideration received (or in some cases receivable) that’s expected to be refunded. • As applicable, an asset—and corresponding adjustment to cost of goods sold (COGS)— for a company’s right to recover products from customers on settling the refund liability A Note that the principles in the ASU are intended to be applied on a contract-by-contract basis. However, the ASU permits, as a practical expedient, application of its guidelines to a portfolio of similar contracts if doing so wouldn’t result in material differences.

In accounting for contracts with refund and return rights, companies will likely want to take advantage of this accommodation. For example, assume Apparel offers its customers the right to return any products purchased up to 30 days after sale, for any reason. Last Tuesday, Apparel sold 100 fuzzy red sweaters to different customers. Based on historical experience, Apparel expects 15 of those sweaters to be returned for a full refund.

Each sweater sells for $80 and costs Apparel $35 to produce. Apparel would record the following journal entries for the sale of the sweaters and the expected refund liability and corresponding asset. Dr. Cash Cr. $8,000 Revenue $6,800 Refund liability $1,200 COGS Recovery asset $2,975 $525 Exchanges by customers of one product for another of the same type, quality, condition, and price (for example, one color or size for another) aren’t considered returns under the ASU. In fact, these types of exchange have no accounting implications under the ASU. Inventory $3,500 Contracts in which a customer may return a defective product in exchange for a functioning product should be evaluated as a warranty. Typically, the ASU requires the same accounting for assurance-type warranties as current GAAP—record a liability and COGS for any probable warranty claims, in accordance with ASC 450-20. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 22 CONTROL TR A NSFERS OV ER TIME In some situations control over a good or service isn’t transferred at a point in time but rather over time. This would occur when one or more of the following conditions is met: Condition Example ex The customer simultaneously receives and consumes the benefits provided by a company as it performs them. A company provides daily cleaning services. The customer benefits from these services as the company performs the work. D The company’s performance creates or enhances an asset (for example, work in process) that the customer controls as the asset is created or enhanced. Developer performs refurbishments on a manufacturing plant owned by a customer. As Developer performs the work, the customer’s asset is enhanced. C The company’s performance doesn’t create an asset with an alternative use to the company, and the company has an enforceable right to payment for performance completed to date. Coder is asked to develop custom software for a customer. The software can’t be transferred to another customer. If the contract is terminated prematurely, Coder has an enforceable right to collect compensation from the customer equal to Coder’s development costs plus a normal profit margin on those services. Recall our earlier example, in which Developer agrees to rebuild a dilapidated warehouse for a customer.

Previously, Developer concluded that the individual performance obligations—demolition, pouring the foundation, framing, installing plumbing lines and electrical fixtures, insulating the walls, installing drywall, and performing finish work— aren’t distinct because they’re interrelated. In other words, each activity represents an input to produce a combined output specified by the customer. Nonetheless, Developer may still be able to recognize revenue over time as the renovation work is performed—in lieu of waiting until the entire job is complete. This accounting outcome would occur if either: • Developer’s performance creates or enhances an asset the customer controls as the asset is created or enhanced.

This may very well be the case if Developer is performing the refurbishment work on customer-owned property. • Developer’s performance doesn’t create an asset with an alternative use (for example, Developer can’t sell the refurbishments to another customer), and Developer has a right to payment for performance completed to date. When revenues are recognized over time, the ASU allows companies to measure performance using either input measures, such as those based on costs or labor hours incurred, or output measures, such as milestones or units produced. However, the entity doesn’t have free choice to select a measure of progress. Instead the performance measure should be determined based on the method that best reflects the pattern in which the entity satisfies its performance obligations, considering the nature of the goods and services being provided to the customer. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 23 Note that under the ASU, a units-of-delivery or production method may only be appropriate if, at the end of the reporting period, the value of any work in progress or units produced but not yet delivered to the customer is immaterial. This is because if customers are gaining control of an asset over time, revenues should be recognized on a corresponding basis. Waiting to recognize revenues until a unit is produced or delivered may fail to properly match the timing of revenue recognition with when control over the goods are transferred to the customer. This outcome could be a significant change in practice for many contractors that currently use the units-of-production or units-of-delivery method to recognize revenue from production contracts. On the other hand, there are expected to be few differences in employing a cost-to-cost or similar input measure of progress under the ASU versus how this type of method is applied under current GAAP. LICENSE S Software and life sciences companies typically grant customers licenses to IP.

The ASU specifies whether revenues from granting a license should be recognized at a point in time or over time. As a first step, a company must determine whether the license is distinct from other goods and services in the contract, as mentioned earlier. Assuming that granting a license represents a distinct performance obligation, revenues would be recognized as follows: • If the underlying IP to which the license relates is “static,” then revenues are recognized at a point in time—namely, when control of the license is transferred to the customer at the beginning of the license period. • If the underlying IP is “dynamic”—that is, it changes over the license period—then revenues from the performance obligation will be recognized over time. Here are some brief examples of how these principles are applied: Example C Revenue Recognition Analysis Coder offers a cloud-based storage solution, which it hosts on its own servers. Coder grants a license to the customer that allows it to access Coder’s cloud solution for 12 months. • The arrangement contains multiple performance obligations, including a license to use Coder’s software, hosting, and storage services. • The license isn’t distinct, because it is highly interrelated with other promised goods or services in the contract. As a result, the arrangement represents a single performance obligation. • The customer simultaneously receives and consumes the benefits provided by Coder’s services.

Hence Coder would recognize revenue from the performance obligation over time. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 2 4 Example C Revenue Recognition Analysis Coder licenses software under a three-year timebased license. Coder also offers “when and if available” upgrades. • The license is distinct from the unspecified upgrades because the customer can benefit from the license even if the unspecified upgrades aren’t provided. • Revenue allocated to the license performance obligation would be recognized upon transfer of the license to the customer. The IP to which the license relates is static. For purposes of the analysis, Coder should ignore the fact that unspecified upgrades will enhance or change the IP because those updates represent a separate performance obligation. • The arrangement doesn’t meet any of the three conditions mentioned previously to recognize revenue over time. B Biotech licenses to a customer the commercialization rights to a drug compound under development.

Biotech also agrees to provide R&D services to ready the drug for regulatory approval. The R&D services could be performed by other vendors, such as contract research organizations. • The license is a distinct performance obligation. This is because the customer can benefit from the license even if Biotech doesn’t provide R&D services.

(Others can perform similar services.) • Revenue allocated to the license would be recognized at a point in time, upon transfer of the license to the customer. The IP subject to the license is static. As with the previous example, Biotech should ignore the fact that its R&D services will enhance the IP, because those services are a distinct performance obligation. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 25 Other Issues Contract Costs The ASU clarifies the types of costs that can and should be capitalized with contracts with customers: Cost Type Discussion Obtaining a contract • Incremental costs of obtaining a contract are those incurred only as a result of the contract’s being obtained. • Incremental costs to obtain a contract are deferred, so long as the seller expects to recover those costs. • Any deferred costs are amortized over the life of the contract (including, as applicable, anticipated contract renewals) in the same pattern as revenue is recognized. • A company may elect to immediately expense these costs if the amortization period would be one year or less. Costs That Qualify Costs That Don’t Qualify • Sales commissions • Customer credit evaluations • Legal expenses in preparing or reviewing a contract Fullfilling a contract • If the costs of fulfilling a contract should be accounted for under other GAAP standards (e.g., ASC 330 or ASC 985-20), then apply those other standards. • If no other GAAP applies, then fulfillment costs should be capitalized if all of the following are true: »» They relate directly to a contract or to an anticipated contract that the entity can specifically identify. »» They generate or enhance resources of the entity that will be used in satisfying performance obligations in the future. »» They’re expected to be recovered under the contract. • Any deferred costs are amortized over the life of the contract (including, as applicable, anticipated contract renewals) in the same pattern as revenue is recognized. Such costs aren’t allowed to be immediately expensed even if the contract will be completed in one year or less. Costs That Qualify Costs That Don’t Qualify • Equipment recalibration costs (if required to fulfill a contract) • Costs of wasted materials, labor, or other resources • Certain design costs (if required to fulfill a contract • Costs related to already satisfied performance obligations Let’s assume that a company establishes a quota for its sales personnel. If an individual sells more than $1 million worth of products in a quarter, he or she will receive a commission of 3 percent of total sales. This type of commission structure may or may not qualify for deferral as a cost of obtaining a contract, depending on facts and circumstances. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 26 Deferring the payment would be appropriate if it were triggered by obtaining a single contract in excess of $1 million. Deferral may also be appropriate if the multiple contracts that cumulatively gave rise to the commission payment all met the conditions, and were accounted for, as a single portfolio. Deferral wouldn’t be appropriate if the payment weren’t associated with, or incremental to, a single customer contract and the company doesn’t account for the group of contracts that gave rise to the commission payment on a portfolio basis. Contract Modifications A contract modification is a change in the scope or price (or both) of a contract that’s approved by the parties to the contract. In the construction industry a contract modification may be described as a change order or a variation. In other industries a contract modification is sometimes called an amendment. D The ASU contains complex guidelines around the accounting for contract modifications. In some cases the modification will be treated as a separate contract and won’t affect the original contract in any way.

In other situations a company will be required to treat a contract modification as a termination of the existing contract and the creation of a new replacement contract. In still other cases a company will account for a contract modification by recording a catch-up journal entry to adjust the cumulative revenue recognized to date on the contract. The ultimate accounting treatment will depend on the nature of the modification. For example, assume Developer agrees to refurbish a facility for a customer.

The 12-month project is expected to cost Developer $1 million to complete, and Developer will charge a fixed $2 million fee for the services. Assume also that the contract has a single performance obligation—the construction services. Revenues will be recognized over time using a cost-to-cost progress measure, because the customer controls the facility during the refurbishment period. Six months into the contract, Developer is about 40 percent complete with the assignment, having incurred $400,000 in cost (and recognizing $800,000 in cumulative revenues to date).

At that time the customer requests that Developer make a significant change to the facility’s layout, which will result in an additional $200,000 of costs. The customer and Developer agree on a price of $500,000 related to the change order. Following the contract modification, the new estimated transaction price and costs are as follows: Original Estimate Change Order New Estimate Transaction price $2,000,000 $500,000 $2,500,000 Contract cost $1,000,000 $200,000 $1,200,000 The change order isn’t considered a separate performance obligation, since the contract amendment doesn’t create a new good or service distinct from the construction services set out in the original contract. Accordingly, Developer will account for the modification as though it were part of the original contract, using a cumulative catch-up approach. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 27 D Developer will update its measure of progress, determining that it has satisfied 33 percent of its performance obligation to date ($400,000 / $1,200,000). This would mean that Developer should recognize cumulative revenues of $825,000 (0.33 x $2,500,000), resulting in Developer recording—at the time of the change order—additional revenue of $25,000 ($825,000 - $800,000) as a catch-up adjustment. Now let’s assume that Developer enters into a second contract with a different customer to perform refurbishment work on customer-owned property. Unfortunately the contract doesn’t go well. Inspectors find toxic materials in the walls, causing Developer to incur $1 million of unanticipated removal and disposal costs.

The customer has refused to reimburse Developer for these additional costs, claiming Developer should have known that similar vintage buildings would contain these harmful materials. The customer further believes Developer should have considered the potential additional remediation costs in its original bid. Even though Developer doesn’t have an agreement with the customer as to the scope and price of the additional work, it’s possible under the ASU that a contract modification exists. As a first step Developer would evaluate whether its claim for recovery of the additional costs is enforceable. Developer would have to evaluate all the facts and consider the laws and regulations of the jurisdiction in which legal action would take place.

Significant judgment is involved in this evaluation. If the Developer does believe the claim is enforceable, it would then determine whether de facto contract modification creates new goods or services that are distinct from the original performance obligations in the contract. In this example no new goods or services would be created—the additional work relates to the same refurbishment services promised under the terms of the original contract. Therefore the claim would be treated as an amendment of the original contract and affect the estimated costs and revenues associated with that arrangement. As a final step Developer would adjust the transaction price of the original contract to consider the variable consideration associated with the claim.

Of course, Developer would also consider the “constraint” on variable consideration, and may conclude that no additional revenue should be recognized because of the uncertainties around the claim. Disclosures One of the FASB’s main goals in issuing the ASU was to improve the disclosures around revenue recognition, believing that under current GAAP the required disclosures about revenue “were limited and lacked cohesion.” As a result the ASU contains extensive new disclosures related to a company’s contracts with customers. Many of these disclosures are quantitative in nature and hence entity-specific. For example, companies will now be required to disclose: • Disaggregated information about revenues.

The ASU provides companies some discretion as to how to break down revenues into meaningful categories. But the objective is to provide users with information about how economic factors affect the nature, amount, timing, and uncertainty of revenue and cash flows. Examples of how revenues can be disaggregated include: »» By geographic region »» By product line .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 28 »» By customer type (e.g., governmental versus corporate entities) »» By timing of revenue recognition (over time or at a point in time) »» By sales channel (e.g., goods sold through distributors versus goods sold directly to end users) »» By any other breakdown that would be helpful for users of the financial statements The FASB expects that most companies will disclose multiple categories of disaggregated information. Note that for public entities, this information will likely not conform to information presented in the segments footnote. As a result the two disclosures will need to be reconciled. • Information about contract balances. This disclosure requires presentation of significant changes in contract assets (e.g., unbilled receivables) and contract liabilities (e.g., deferred revenues and refund liabilities) during the reporting period. • Information about the timing of future revenue recognition.

The ASU requires disclosure of the amount of the transaction price that’s been allocated to performance obligations that haven’t been satisfied as of the balance sheet date and the approximate timing as to when those performance obligations are expected to result in revenue recognition. Companies will also have to include qualitative disclosures around the significant judgments they made in applying the guidance in the ASU and the policies they used in determining the transaction price (especially in relation to estimating variable consideration) and the stand-alone selling prices of performance obligations. The ASU provides a number of accommodations for nonpublic entities, simplifying or eliminating a number of the disclosures otherwise required for public entities. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 29 We’re Here to Help The goal of this guide is to describe some—but certainly not all—of the potential changes that will result from the new ASU. We also wanted to highlight some of the implications of the new guidelines that may apply at your business. The FASB and the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants have announced resource groups to help identify and resolve implementation issues arising from the new standard. In the meantime, if you have questions on how the new standard could affect your business, please contact your Moss Adams professional. The material appearing in this communication is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as advice of any kind, including, without limitation, legal, accounting, or investment advice. This information is not intended to create, and receipt does not constitute, a legal relationship, including, but not limited to, an accountant-client relationship. Although this information may have been prepared by professionals, they should not be used as a substitute for professional services.

If legal, accounting, investment, or other professional advice is required, the services of a professional should be sought. About Moss Adams Nationwide, Moss Adams and its affiliates provide insight and expertise integral to your success. Moss Adams LLP is a national leader in assurance, tax, consulting, risk management, transaction, and wealth services. W W W. M O S S A D A M S .C O M Moss Adams Wealth Advisors LLC provides investment management, personal financial planning, and insurance strategies to help you build and preserve your wealth. W W W. M O S S A D A M S W E A LT H A D V I S O R S .C O M Moss Adams Capital LLC offers strategic advisory and investment banking services, helping you create greater value in your business. W W W.

M O S S A D A M S C A P I TA L .C O M .

Accordingly, Apparel would be unable to record a gain upon sale of the building. However, under newly created ASC 610-20-40, Apparel would recognize a gain upon transferring control of the building to the buyer. Apparel would consider the potential guarantee in measuring the value of the gain to be recognized. . MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 4 B Let’s say Biotech performs research on a new drug compound on behalf of a customer. Biotech previously received a nonrefundable up-front payment and is entitled to a $25 million nonrefundable milestone payment upon the successful enrollment of 100 patients into a Phase III clinical trial. Although the activities necessary to complete Phase III enrollment are substantive, Biotech believes it is 70 percent likely to achieve the milestone. Under current GAAP, Biotech would likely recognize the up-front nonrefundable payment over the period it performs services, using a proportional performance methodology. Biotech could elect to recognize the milestone payment in its entirety when the milestone is achieved. C Under the new ASU, given the likelihood of achieving the milestone, Biotech would include the milestone payment as part of the “transaction price.” Accordingly, as Biotech performs services, it would recognize revenue for both the up-front and milestone portions of the transaction price—even prior to actually achieving the milestone. Let’s say Coder delivers a license for version 11.0 of its enterprise risk management software, together with one year of 24x7 telephone support. There’s no vendor-specific objective evidence (VSOE) of the fair value of the telephone support. Under current GAAP, the entire license fee is deferred and recognized as revenue over the one-year support period. D Under the new ASU, a portion of the arrangement fee likely would be recognized as revenue upon delivery of the license. The balance would be recognized as revenue ratably over the period telephone support is provided. And finally, let’s say Developer is building 10 apartment units overlooking a tropical beach. Each unit is under contract, and Developer may not transfer a unit to another party.

Buyers of the units (the customers in this example) will make progress payments to Developer during the construction period. If a buyer defaults, Developer may elect to complete the construction of the unit and obtain an enforceable legal right for full payment from the defaulting buyer. Under current GAAP, each of the units is a separate profit center. Developer would likely recognize revenue once all work for a given unit is completed and the unit is legally transferred to the buyer at closing. But under the new ASU, each unit would represent a separate customer contract.

Developer would likely recognize revenue as progress toward completing each unit is made, based on input measures such as labor hours or costs incurred. These are just a few examples across just a handful of industries. However, the ASU will have a broad impact on most every company. This is especially true for entities that sell bundled product and service offerings, provide return or refund rights, or occasionally amend contract terms. In this guide we’ll examine the basic principle behind the new guidelines, discuss the transition process, and then delve into the major changes the ASU brings about—providing examples along the way to help guide your understanding. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 5 The Basic Principle The ASU contains an overarching principle: that a company should recognize revenue when it transfers goods or services to a customer. The amount of revenue recognized should represent the consideration “to which the entity (i.e., the seller) expects to be entitled.” To apply these principles, the ASU outlines a five-step process: STEP 1 Identify the contract with a customer. D STEP 2 Identify the separate performance obligations in the contract. STEP 3 Determine the transaction price. STEP 4 Allocate the transaction price to the separate performance obligations in the contract. STEP 5 Recognize revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation. Companies won’t always perform these steps sequentially. For example, let’s say Developer enters into a series of contracts with a customer to construct a building and parking garage. The parties separately agree for Developer to install surveillance equipment and provide monitoring services on an annual basis, once the facilities are constructed. Before identifying all the separate performance obligations (Step 2) in the various arrangements, Developer may first want to simultaneously perform Steps 1 and 3 to identify whether the various contracts should be combined and, if so, determine the transaction price of the total accounting unit. Overall, it’s really a change in mind-set. ex Much of today’s GAAP is built around a “risks and rewards” notion: Revenues are recognized when substantially all the risk of loss from the sale of goods or services has passed to the customer.

The trigger for revenue recognition under the ASU is based on the transfer of control over a good or service to the customer. As a result, the new model could lead to very different revenue recognition patterns and timing. For example, let’s say a manufacturer produces and sells fishing rods to a distributor. The manufacturer offers the distributor generous return rights and price protection guarantees. In turn, the distributor sells the fishing rods to a retail store. Under current GAAP, the manufacturer may recognize revenue on a “sell through” basis. This means it would wait to report revenue until its customer, the distributor, sells the fishing rods through to the retail store. .

MO S S A DA M S RE V ENUE REC OGNI T ION | 6 The manufacturer may have selected this accounting policy because it retained a number of risks following delivery of the products to the distributor. Specifically, the arrangement fee may not be fixed or determinable—a necessary condition for recognizing revenue under today’s accounting rules—because of the generous return rights and price protection guarantees included in the contract. Under the ASU, the manufacturer will likely recognize revenue upon delivery of the fishing rods to the distributor. This is because control over those products has transferred to the distributor at that time. The manufacturer would consider the risks of price concessions and future returns when determining the transaction price in Step 3 of the process—that is, in calculating how much revenue to recognize at the time of transfer. In some circumstances the new five-step process may result in the same accounting outcome as current GAAP, but the logic and reasoning for reaching those conclusions may change. .