Description

Spotlight

Asia

Kroll Quarterly

M&A Newsletter

September 2015

Chinese investment in Australia

In 2014, China’s outbound direct investment soared to a record high of more than

US$100bn, a large portion of which has been focused on its southern regional neighbour

Australia. For the first time, China became Australia’s largest source of approved proposed

investment with an aggregate of US$19.7bn in 2013-14, a 75% increase from US$11.3bn

in 2012-13, according to the Australian government. China outperformed long-time

top investor the United States, which yielded US$12.5bn worth of approved investment

proposals, down from US$14.7bn in the previous year.

For M&A, 2014 closed with 20 announced deals worth US$3.7bn from Chinese bidders,

down from US$4.8bn in 2013, albeit at almost twice the deal volume, due in part to

a shift towards mid-market deals. Activity in H1 2015 kept pace with 2014, closing with

10 announced deals grossing US$1.8bn.

The outlook for the rest of the year, however, is clouded amid economic uncertainty arising from China’s deceleration in growth, and compounded Chinese M&A into Australia (2010 - H1 2015) by its stock market volatility. 25 7,000 6,000 20 Deal volume 5,000 15 4,000 3,000 10 2,000 5 1,000 Deal value US$m China’s outbound investment has traditionally been driven by stateowned enterprises (SOEs) in search of natural resources, raw materials and technological know-how to fuel the country’s We are pleased to present the latest edition of Spotlight Asia, Kroll’s quarterly M&A newsletter, produced in association with Mergermarket. Contents include: • An overview of Chinese FDI and M&A into Australia • A look at the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement and what it means for Chinese investment in Australia • Analyses of activity and trends in the mining, real estate, agriculture and infrastructure sectors • An interview with Violet Ho, Senior Managing Director, and Richard Dailly, Managing Director at Kroll, on conducting due diligence on foreign investors or buyers before entering into crossborder transactions Subscribe at http://asia.kroll.com to make sure you receive our next Spotlight Asia issue 0 0 2010 Deal volume 2011 2012 Deal value 2013 2014 H1 2015 Source: Mergermarket Kroll Quarterly M&A Newsletter – September 2015 . Australia industrialisation and modernisation efforts. Much of this offshore interest has been channelled to Australia, by means of its economic maturity and low political risk, regulatory efficiency and transparency, rule of law, strong equity markets, wealth of quality resource assets and geographical proximity to China. Australia’s low cash interest rates, combined with a bearish Australian dollar, have intensified its appeal. While China’s interest in Australia has been consistent, it is nonetheless a transformation in the investment landscape that gave rise to 2014’s record values. China’s investments in Australia are changing: China’s emphasis has swung from resource-intensive investments to include more acquisitions of real estate, agribusiness, tourism, life sciences, renewable energy and infrastructure assets. The China-Australia Free Trade Agreement The China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA) was signed on 17 June 2015, paving the way for greater ease of trade between the two nations. A possible forerunner to growth in the M&A market, the ChAFTA signals the Australian government’s recognition of the importance of Chinese capital as fuel for the domestic economy. Expected to act as a major deal driver for further investment from China, ChAFTA liberalises the regulatory procedures which Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) imposes on inbound investment, raising the screening threshold for private Chinese investors in non-sensitive sectors from AU$252m Target sectors by volume and value (2010 - H1 2015) 1.0% 1.5% 0.5% 0.4% 1.9% (US$179.6m) to AU$1.094bn (US$779.5m).

FIRB screens foreign investment with considerations of national interest in mind, such as that of national security and healthy competition. ChAFTA has also locked in commitments to eliminate tariffs across a wide range of agriculture, resources, energy and manufactured exports to China. The signing of ChAFTA follows free trade agreements with Japan and Korea, as well as the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand FTA, heralding the importance of trade and investment with Australia’s neighbours. Mining Traditionally favoured by Chinese SOEs, mining was the top sector for M&A in 2014. However, activity was not as intense as in years past, due in part to a paucity of the sort of mega deals that characterised Australia’s decade-long mining boom, such as the US$7.25bn merger between Australia’s Gloucester Coal and Chinese-owned Yancoal Australia in 2012. Interest in clean energy may gradually dampen the sector’s performance in future, but is unlikely to maim it in the short run. Under China’s urbanisation plans, approximately 100m rural inhabitants are to migrate to cities by 2020, promising a rise in absolute demand for steel and coal as the country caters to the resultant housing and infrastructure needs.

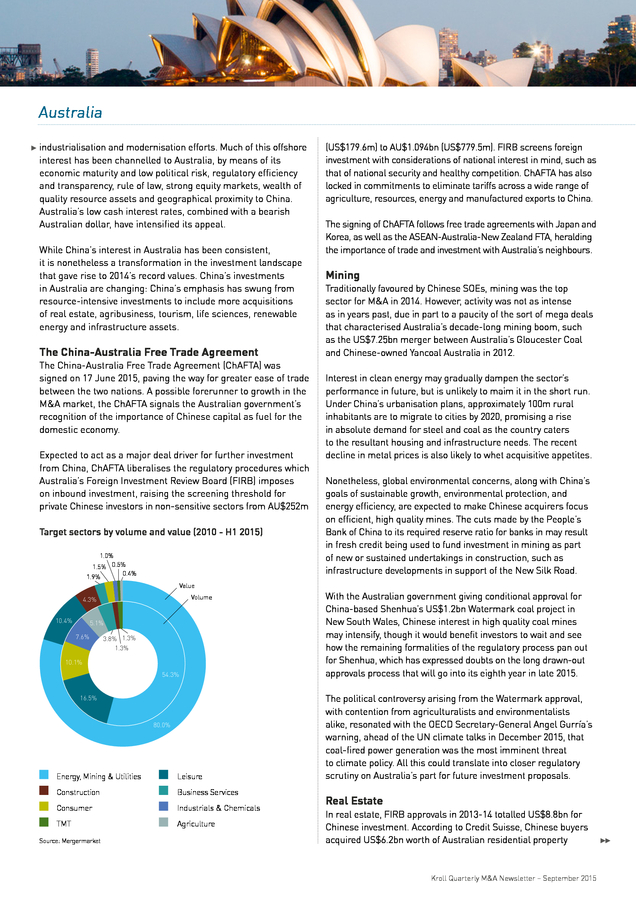

The recent decline in metal prices is also likely to whet acquisitive appetites. Nonetheless, global environmental concerns, along with China’s goals of sustainable growth, environmental protection, and energy efficiency, are expected to make Chinese acquirers focus on efficient, high quality mines. The cuts made by the People’s Bank of China to its required reserve ratio for banks in may result in fresh credit being used to fund investment in mining as part of new or sustained undertakings in construction, such as infrastructure developments in support of the New Silk Road. Value Volume 4.3% 10.4% 5.1% 7.6% 3.8% 1.3% 1.3% 10.1% 54.3% 16.5% 80.0% Energy, Mining & Utilities Leisure Construction Business Services Consumer Industrials & Chemicals TMT Agriculture Source: Mergermarket With the Australian government giving conditional approval for China-based Shenhua’s US$1.2bn Watermark coal project in New South Wales, Chinese interest in high quality coal mines may intensify, though it would benefit investors to wait and see how the remaining formalities of the regulatory process pan out for Shenhua, which has expressed doubts on the long drawn-out approvals process that will go into its eighth year in late 2015. The political controversy arising from the Watermark approval, with contention from agriculturalists and environmentalists alike, resonated with the OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría’s warning, ahead of the UN climate talks in December 2015, that coal-fired power generation was the most imminent threat to climate policy. All this could translate into closer regulatory scrutiny on Australia’s part for future investment proposals. Real Estate In real estate, FIRB approvals in 2013-14 totalled US$8.8bn for Chinese investment.

According to Credit Suisse, Chinese buyers acquired US$6.2bn worth of Australian residential property Kroll Quarterly M&A Newsletter – September 2015 . Due diligence on investors makes for deal success The shifting dynamics of Chinese investment into Australia abound with both risks and rich returns at every turn. It is up to the shrewd Australian business to learn to navigate its way around potential pitfalls such as corruption and fraud. Kroll’s Violet Ho, Senior Managing Director, and Richard Dailly, Managing Director, shed light on these concerns. As an Australian company, what risks should a potential recipient of investment consider before working with a Chinese investor? Australian businesses belonging to labour-intensive sectors should consider the labour obligations they owe to existing employees, either under labour law and regulations, or through organised arrangements with key stakeholders such as labour unions. Potential recipients of investment should also take into account post-transactional considerations relating to the integration phase of M&A, such as the compatibility between new foreign management and local employees in terms of governance, corporate culture and the expectations of community stakeholders. It is in the recipient’s interest to assess whether a prospective investor is likely to live up to expectations, especially when original stakeholders retain minority ownership.

There is the question of whether the potential investor has developed a sufficiently thorough understanding of Australia’s business realities, as well as legal and ethical practice obligations, and whether it has the wherewithal to address a multitude of possible concerns, ranging from environmental issues to safety standards and additional overhead costs. One of the biggest risks is that of working with investors whose funds may be of dubious origins. This is especially significant in light of China’s headline-grabbing anti-corruption purge. If an Australian company has been bought with “flight capital” obtained via illegitimate means, the entity may become subject to both financial and reputational risks, should either the Chinese government track down corrupt officials and laundered funds in an attempt to recoup losses, or the Australian government or competitors determine integrity weaknesses on their own. Should the new owner of an acquired entity be prosecuted on the Chinese side, the Chinese government could seize control of the delinquent investor’s offshore assets, potentially nationalising the acquired entity or otherwise leaving the company and its employees in a state of management and operational limbo. How can anyone in Australia truly know who they are dealing with in China, given China’s opacity? Conducting pre-transactional due diligence is vital to achieving an alignment of interest between the different parties, enabling each side to become more aware of who they are really dealing with and to make astute, better-informed decisions in the interests of a sustainable, risk-managed transaction and relationship.

To trustingly close transactions without sufficient knowledge of the opposite party is high risk and invites difficulties. Australian businesses also need to undertake a duty of care, to a range of internal and external stakeholders, when making due diligence decisions. The due diligence process offers an invaluable window of opportunity for the sell-side to verify and validate what it considers attractive in the potential deal, such as the financial standing and resources of the buyer, certain clauses in the contract, or the ability of the buyer to complete the transaction. Australian sellers also need to know the reputational impact and political exposure buyers could bring, and whether buyers have satisfactory track records when it comes to intellectual property, labour or environmental protection issues. These are some of the things a local business should learn in good faith before entering a transaction, reserving enough room for the different parties to reconcile any differences they uncover, or to prepare response plans for contingencies, building in adequate warranties that allow them to seek recourse or even walk away from a transaction if certain conditions are not fulfilled. Should Australian businesses be concerned that some investments might simply be a way of off-shoring or laundering money? There are concerns that inbound foreign investment is sometimes at risk of being a means to illegitimate ends, or of posing serious challenges to the core values of the recipient parties and stakeholder communities. Some Australian businesses harbour reservations when dealing with foreign investors, mainly because they do not know who they are dealing with and lack the means to find out. They are also unsure of how to mitigate potential regulatory backlash.

This can create a sense of unease and also influence the negotiating strategy deployed to maximise sell-side valuations. Such fears are not unfounded, but local businesses need to know that they can get to know a would-be foreign investor, and that the crux of the matter lies in knowing where to get help. Procedures in Australia for dealing with overseas investors are sometimes not as sophisticated as those of other developed economies. Rather than run the risk of slipping into xenophobic hysteria, there needs to be an education process – local businesses need to acquire a working understanding of what to look for, what to look into, and how to interpret information they come across in the process of getting to know an interested foreign party.

The key is to be proactive and in control of the process. While there is a need to tread with caution, local businesses should nonetheless refrain from jumping to conclusions, bearing in mind that it is not always easy to differentiate between legitimate red flags and the red herrings of intercultural misunderstanding. For example, foreign buyers paying cash for real estate purchases may look questionable, but often constitute legitimate transactions motivated by quotidian locale-specific reasons.

For example, Chinese property buyers are accustomed to making cash payments due to tight mortgage restrictions in China. Kroll Quarterly M&A Newsletter – September 2015 . Australia in 2013-14, and another US$42.3bn is expected to be invested in the next six years, far more than the US$20bn over the past six years. The Australian government requires non-resident foreign investors to buy new-build properties instead of established housing, and investment interest has been focused on apartments close to city centres, universities and public transportation networks, as opposed to detached houses. Purchases have been concentrated in Sydney and Melbourne, as well as Brisbane. Seeing opportunities in demand for Australian housing, Chinese developers have been entering the Australian market as the Chinese government puts in braking measures to dampen price gains in the domestic housing market. China’s anti-corruption drive, combined with Canada’s cancellation of its investor visa programme in 2014, may have driven investors with flight capital to flock to Australia in hopes of a soft landing. In the aftermath of stock market volatility in China, wealthier investors are expected to look for a relatively stable alternative to stocks, and to the Australian property market for a tried-andtrue safe haven in which to park their funds, which could in turn lead to inbound M&A activity generated by Chinese developers. Developers need to be wary of the risk of average investors being unable to undertake new investments or to honour payments for investments already underway, having been singed in the Chinese stock market turmoil. Investors attempting to bail out of stocks may have been stymied by the Chinese government’s market correction measures, such as the ban preventing shareholders with stakes of more than five percent in listed firms from selling for six months. With their share prices taking a hit, Chinalisted real estate companies emerged from the Shanghai share market tumult with an average debt-to-enterprise value of 75%, according to Citi, which may reduce acquisitive M&A activity as developers seek to reduce debt. Agriculture and agribusiness With the signing of the ChAFTA, Australian agribusiness targets look even more compelling to Chinese investors, since the removal of various tariffs means Australian agricultural products can arrive in China at a highly competitive cost, potentially generating more demand and increasing profit margins. The Chinese government has also expressed interest in backing Australia’s plan of developing Northern Australia to become part of Asia’s “food bowl”, displaying increased interest not only in the agriculture and food processing sector, but also in the concatenated infrastructure sector, which provides the roads, dams, air-strips and ports upon which the export of agriculture and food products depend. A major risk of investing in agribusiness lies in the unpredictability of the climate.

Foreign investors unfamiliar with the territory need to invest more time and funds into acquiring the knowledge and technology for running agricultural enterprises in the land, or structure their investments through managed agricultural funds. Infrastructure Given their close proximity to major Asian trading hubs, the privatisations of Australian state-owned ports have been particularly attractive to Chinese SOEs, as control of such premium ports would streamline trade logistics and transportation for China’s enterprise interests in other sectors. The largest single Chinese investment in 2014 was the acquisition of construction service provider John Holland. Of high strategic importance was China Merchants Group’s co-investment with Hastings Funds Management in an US$1.2bn deal to secure 98-year lease rights to the Port of Newcastle. Potential buyers and sellers need to be fully informed of the jurisdiction-specific regulatory issues surrounding M&A between China and Australia, ensuring satisfactory and timely completion, so that regulatory uncertainty does not translate into competitive disadvantage. Chinese investment in agribusiness is driven by a need to ensure food security and to maintain safe sources of food products amid a growing number of scandals and food scares at home. To tighten its scrutiny of foreign purchases of farmland, the FIRB lowered its screening threshold from AU$252m (US$179.6m) to AU$15m (US$10.7m) from 1 March 2015. Australia’s agricultural exports are placed at a premium for the country’s pristine reputation in upholding uncompromised food safety standards and quality. Contact us Asia: Violet Ho vho@kroll.com +852 2884 7777 Asia: Richard Dailly rdailly@kroll.com +65 6645 4521 EMEA: Neil Kirton nkirton@kroll.com +44 207 029 5204 Americas: Betsy Blumenthal bblument@kroll.com +1 415 743 4825 The information contained herein is based on currently available sources and should be understood to be information of a general nature only. The information is not intended to be taken as advice with respect to any individual situation and cannot be relied upon as such.

This document is owned by Kroll and Mergermarket, and its contents, or any portion thereof, may not be copied or reproduced in any form without permission of Kroll. Clients may distribute for their own internal purposes only. All deal details and M&A figures quoted are proprietary Mergermarket data unless otherwise stated. M&A figures may include deals that fall outside Mergermarket’s official inclusion criteria.

All economic data comes from the World Bank unless otherwise stated. All $ symbols refer to US dollars. Adrian Ng adrian.ng@mergermarket.com +852 2158 9743 .

The outlook for the rest of the year, however, is clouded amid economic uncertainty arising from China’s deceleration in growth, and compounded Chinese M&A into Australia (2010 - H1 2015) by its stock market volatility. 25 7,000 6,000 20 Deal volume 5,000 15 4,000 3,000 10 2,000 5 1,000 Deal value US$m China’s outbound investment has traditionally been driven by stateowned enterprises (SOEs) in search of natural resources, raw materials and technological know-how to fuel the country’s We are pleased to present the latest edition of Spotlight Asia, Kroll’s quarterly M&A newsletter, produced in association with Mergermarket. Contents include: • An overview of Chinese FDI and M&A into Australia • A look at the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement and what it means for Chinese investment in Australia • Analyses of activity and trends in the mining, real estate, agriculture and infrastructure sectors • An interview with Violet Ho, Senior Managing Director, and Richard Dailly, Managing Director at Kroll, on conducting due diligence on foreign investors or buyers before entering into crossborder transactions Subscribe at http://asia.kroll.com to make sure you receive our next Spotlight Asia issue 0 0 2010 Deal volume 2011 2012 Deal value 2013 2014 H1 2015 Source: Mergermarket Kroll Quarterly M&A Newsletter – September 2015 . Australia industrialisation and modernisation efforts. Much of this offshore interest has been channelled to Australia, by means of its economic maturity and low political risk, regulatory efficiency and transparency, rule of law, strong equity markets, wealth of quality resource assets and geographical proximity to China. Australia’s low cash interest rates, combined with a bearish Australian dollar, have intensified its appeal. While China’s interest in Australia has been consistent, it is nonetheless a transformation in the investment landscape that gave rise to 2014’s record values. China’s investments in Australia are changing: China’s emphasis has swung from resource-intensive investments to include more acquisitions of real estate, agribusiness, tourism, life sciences, renewable energy and infrastructure assets. The China-Australia Free Trade Agreement The China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA) was signed on 17 June 2015, paving the way for greater ease of trade between the two nations. A possible forerunner to growth in the M&A market, the ChAFTA signals the Australian government’s recognition of the importance of Chinese capital as fuel for the domestic economy. Expected to act as a major deal driver for further investment from China, ChAFTA liberalises the regulatory procedures which Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) imposes on inbound investment, raising the screening threshold for private Chinese investors in non-sensitive sectors from AU$252m Target sectors by volume and value (2010 - H1 2015) 1.0% 1.5% 0.5% 0.4% 1.9% (US$179.6m) to AU$1.094bn (US$779.5m).

FIRB screens foreign investment with considerations of national interest in mind, such as that of national security and healthy competition. ChAFTA has also locked in commitments to eliminate tariffs across a wide range of agriculture, resources, energy and manufactured exports to China. The signing of ChAFTA follows free trade agreements with Japan and Korea, as well as the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand FTA, heralding the importance of trade and investment with Australia’s neighbours. Mining Traditionally favoured by Chinese SOEs, mining was the top sector for M&A in 2014. However, activity was not as intense as in years past, due in part to a paucity of the sort of mega deals that characterised Australia’s decade-long mining boom, such as the US$7.25bn merger between Australia’s Gloucester Coal and Chinese-owned Yancoal Australia in 2012. Interest in clean energy may gradually dampen the sector’s performance in future, but is unlikely to maim it in the short run. Under China’s urbanisation plans, approximately 100m rural inhabitants are to migrate to cities by 2020, promising a rise in absolute demand for steel and coal as the country caters to the resultant housing and infrastructure needs.

The recent decline in metal prices is also likely to whet acquisitive appetites. Nonetheless, global environmental concerns, along with China’s goals of sustainable growth, environmental protection, and energy efficiency, are expected to make Chinese acquirers focus on efficient, high quality mines. The cuts made by the People’s Bank of China to its required reserve ratio for banks in may result in fresh credit being used to fund investment in mining as part of new or sustained undertakings in construction, such as infrastructure developments in support of the New Silk Road. Value Volume 4.3% 10.4% 5.1% 7.6% 3.8% 1.3% 1.3% 10.1% 54.3% 16.5% 80.0% Energy, Mining & Utilities Leisure Construction Business Services Consumer Industrials & Chemicals TMT Agriculture Source: Mergermarket With the Australian government giving conditional approval for China-based Shenhua’s US$1.2bn Watermark coal project in New South Wales, Chinese interest in high quality coal mines may intensify, though it would benefit investors to wait and see how the remaining formalities of the regulatory process pan out for Shenhua, which has expressed doubts on the long drawn-out approvals process that will go into its eighth year in late 2015. The political controversy arising from the Watermark approval, with contention from agriculturalists and environmentalists alike, resonated with the OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría’s warning, ahead of the UN climate talks in December 2015, that coal-fired power generation was the most imminent threat to climate policy. All this could translate into closer regulatory scrutiny on Australia’s part for future investment proposals. Real Estate In real estate, FIRB approvals in 2013-14 totalled US$8.8bn for Chinese investment.

According to Credit Suisse, Chinese buyers acquired US$6.2bn worth of Australian residential property Kroll Quarterly M&A Newsletter – September 2015 . Due diligence on investors makes for deal success The shifting dynamics of Chinese investment into Australia abound with both risks and rich returns at every turn. It is up to the shrewd Australian business to learn to navigate its way around potential pitfalls such as corruption and fraud. Kroll’s Violet Ho, Senior Managing Director, and Richard Dailly, Managing Director, shed light on these concerns. As an Australian company, what risks should a potential recipient of investment consider before working with a Chinese investor? Australian businesses belonging to labour-intensive sectors should consider the labour obligations they owe to existing employees, either under labour law and regulations, or through organised arrangements with key stakeholders such as labour unions. Potential recipients of investment should also take into account post-transactional considerations relating to the integration phase of M&A, such as the compatibility between new foreign management and local employees in terms of governance, corporate culture and the expectations of community stakeholders. It is in the recipient’s interest to assess whether a prospective investor is likely to live up to expectations, especially when original stakeholders retain minority ownership.

There is the question of whether the potential investor has developed a sufficiently thorough understanding of Australia’s business realities, as well as legal and ethical practice obligations, and whether it has the wherewithal to address a multitude of possible concerns, ranging from environmental issues to safety standards and additional overhead costs. One of the biggest risks is that of working with investors whose funds may be of dubious origins. This is especially significant in light of China’s headline-grabbing anti-corruption purge. If an Australian company has been bought with “flight capital” obtained via illegitimate means, the entity may become subject to both financial and reputational risks, should either the Chinese government track down corrupt officials and laundered funds in an attempt to recoup losses, or the Australian government or competitors determine integrity weaknesses on their own. Should the new owner of an acquired entity be prosecuted on the Chinese side, the Chinese government could seize control of the delinquent investor’s offshore assets, potentially nationalising the acquired entity or otherwise leaving the company and its employees in a state of management and operational limbo. How can anyone in Australia truly know who they are dealing with in China, given China’s opacity? Conducting pre-transactional due diligence is vital to achieving an alignment of interest between the different parties, enabling each side to become more aware of who they are really dealing with and to make astute, better-informed decisions in the interests of a sustainable, risk-managed transaction and relationship.

To trustingly close transactions without sufficient knowledge of the opposite party is high risk and invites difficulties. Australian businesses also need to undertake a duty of care, to a range of internal and external stakeholders, when making due diligence decisions. The due diligence process offers an invaluable window of opportunity for the sell-side to verify and validate what it considers attractive in the potential deal, such as the financial standing and resources of the buyer, certain clauses in the contract, or the ability of the buyer to complete the transaction. Australian sellers also need to know the reputational impact and political exposure buyers could bring, and whether buyers have satisfactory track records when it comes to intellectual property, labour or environmental protection issues. These are some of the things a local business should learn in good faith before entering a transaction, reserving enough room for the different parties to reconcile any differences they uncover, or to prepare response plans for contingencies, building in adequate warranties that allow them to seek recourse or even walk away from a transaction if certain conditions are not fulfilled. Should Australian businesses be concerned that some investments might simply be a way of off-shoring or laundering money? There are concerns that inbound foreign investment is sometimes at risk of being a means to illegitimate ends, or of posing serious challenges to the core values of the recipient parties and stakeholder communities. Some Australian businesses harbour reservations when dealing with foreign investors, mainly because they do not know who they are dealing with and lack the means to find out. They are also unsure of how to mitigate potential regulatory backlash.

This can create a sense of unease and also influence the negotiating strategy deployed to maximise sell-side valuations. Such fears are not unfounded, but local businesses need to know that they can get to know a would-be foreign investor, and that the crux of the matter lies in knowing where to get help. Procedures in Australia for dealing with overseas investors are sometimes not as sophisticated as those of other developed economies. Rather than run the risk of slipping into xenophobic hysteria, there needs to be an education process – local businesses need to acquire a working understanding of what to look for, what to look into, and how to interpret information they come across in the process of getting to know an interested foreign party.

The key is to be proactive and in control of the process. While there is a need to tread with caution, local businesses should nonetheless refrain from jumping to conclusions, bearing in mind that it is not always easy to differentiate between legitimate red flags and the red herrings of intercultural misunderstanding. For example, foreign buyers paying cash for real estate purchases may look questionable, but often constitute legitimate transactions motivated by quotidian locale-specific reasons.

For example, Chinese property buyers are accustomed to making cash payments due to tight mortgage restrictions in China. Kroll Quarterly M&A Newsletter – September 2015 . Australia in 2013-14, and another US$42.3bn is expected to be invested in the next six years, far more than the US$20bn over the past six years. The Australian government requires non-resident foreign investors to buy new-build properties instead of established housing, and investment interest has been focused on apartments close to city centres, universities and public transportation networks, as opposed to detached houses. Purchases have been concentrated in Sydney and Melbourne, as well as Brisbane. Seeing opportunities in demand for Australian housing, Chinese developers have been entering the Australian market as the Chinese government puts in braking measures to dampen price gains in the domestic housing market. China’s anti-corruption drive, combined with Canada’s cancellation of its investor visa programme in 2014, may have driven investors with flight capital to flock to Australia in hopes of a soft landing. In the aftermath of stock market volatility in China, wealthier investors are expected to look for a relatively stable alternative to stocks, and to the Australian property market for a tried-andtrue safe haven in which to park their funds, which could in turn lead to inbound M&A activity generated by Chinese developers. Developers need to be wary of the risk of average investors being unable to undertake new investments or to honour payments for investments already underway, having been singed in the Chinese stock market turmoil. Investors attempting to bail out of stocks may have been stymied by the Chinese government’s market correction measures, such as the ban preventing shareholders with stakes of more than five percent in listed firms from selling for six months. With their share prices taking a hit, Chinalisted real estate companies emerged from the Shanghai share market tumult with an average debt-to-enterprise value of 75%, according to Citi, which may reduce acquisitive M&A activity as developers seek to reduce debt. Agriculture and agribusiness With the signing of the ChAFTA, Australian agribusiness targets look even more compelling to Chinese investors, since the removal of various tariffs means Australian agricultural products can arrive in China at a highly competitive cost, potentially generating more demand and increasing profit margins. The Chinese government has also expressed interest in backing Australia’s plan of developing Northern Australia to become part of Asia’s “food bowl”, displaying increased interest not only in the agriculture and food processing sector, but also in the concatenated infrastructure sector, which provides the roads, dams, air-strips and ports upon which the export of agriculture and food products depend. A major risk of investing in agribusiness lies in the unpredictability of the climate.

Foreign investors unfamiliar with the territory need to invest more time and funds into acquiring the knowledge and technology for running agricultural enterprises in the land, or structure their investments through managed agricultural funds. Infrastructure Given their close proximity to major Asian trading hubs, the privatisations of Australian state-owned ports have been particularly attractive to Chinese SOEs, as control of such premium ports would streamline trade logistics and transportation for China’s enterprise interests in other sectors. The largest single Chinese investment in 2014 was the acquisition of construction service provider John Holland. Of high strategic importance was China Merchants Group’s co-investment with Hastings Funds Management in an US$1.2bn deal to secure 98-year lease rights to the Port of Newcastle. Potential buyers and sellers need to be fully informed of the jurisdiction-specific regulatory issues surrounding M&A between China and Australia, ensuring satisfactory and timely completion, so that regulatory uncertainty does not translate into competitive disadvantage. Chinese investment in agribusiness is driven by a need to ensure food security and to maintain safe sources of food products amid a growing number of scandals and food scares at home. To tighten its scrutiny of foreign purchases of farmland, the FIRB lowered its screening threshold from AU$252m (US$179.6m) to AU$15m (US$10.7m) from 1 March 2015. Australia’s agricultural exports are placed at a premium for the country’s pristine reputation in upholding uncompromised food safety standards and quality. Contact us Asia: Violet Ho vho@kroll.com +852 2884 7777 Asia: Richard Dailly rdailly@kroll.com +65 6645 4521 EMEA: Neil Kirton nkirton@kroll.com +44 207 029 5204 Americas: Betsy Blumenthal bblument@kroll.com +1 415 743 4825 The information contained herein is based on currently available sources and should be understood to be information of a general nature only. The information is not intended to be taken as advice with respect to any individual situation and cannot be relied upon as such.

This document is owned by Kroll and Mergermarket, and its contents, or any portion thereof, may not be copied or reproduced in any form without permission of Kroll. Clients may distribute for their own internal purposes only. All deal details and M&A figures quoted are proprietary Mergermarket data unless otherwise stated. M&A figures may include deals that fall outside Mergermarket’s official inclusion criteria.

All economic data comes from the World Bank unless otherwise stated. All $ symbols refer to US dollars. Adrian Ng adrian.ng@mergermarket.com +852 2158 9743 .