How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth – September 2015

McKinsey Global Institute

Description

THE POWER OF PARITY:

HOW ADVANCING WOMEN’S

EQUALITY CAN ADD $12 TRILLION

TO GLOBAL GROWTH

SEPTEMBER 2015

HIGHLIGHTS

25

Labor-force participation,

hours worked, and

productivity

41

Equality in society

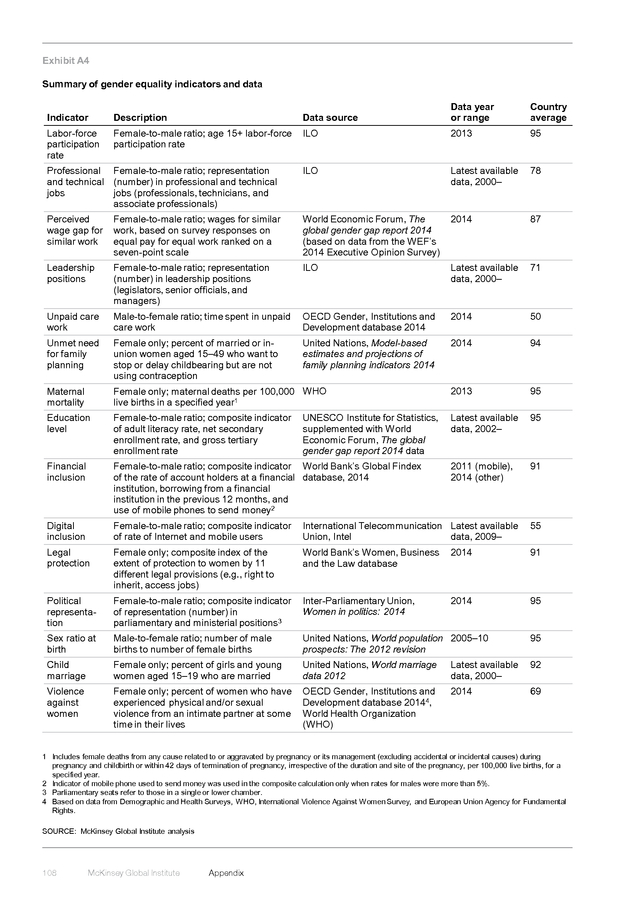

81

Scope for broader action

by the private sector

. In the 25 years since its founding, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) has

sought to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy.

As the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, MGI

aims to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the

facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions.

MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management,

employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business

leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic

industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces

affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have

covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses

on six themes: productivity and growth, natural resources, labor markets,

the evolution of global financial markets, the economic impact of technology

and innovation, and urbanization.

Recent reports have assessed global flows; the economies of Brazil, Mexico, Nigeria, and Japan; China’s digital transformation; India’s path from poverty to empowerment; affordable housing; the effects of global debt; and the economics of tackling obesity. MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company directors: Richard Dobbs, James Manyika, and Jonathan Woetzel. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, and Jaana Remes serve as MGI partners. Project teams are led by the MGI partners and a group of senior fellows, and include consultants from McKinsey & Company’s offices around the world.

These teams draw on McKinsey & Company’s global network of partners and industry and management experts. In addition, leading economists, including Nobel laureates, act as research advisers. The partners of McKinsey & Company fund MGI’s research; it is not commissioned by any business, government, or other institution. For further information about MGI and to download reports, please visit www.mckinsey.com/mgi. Copyright © McKinsey & Company 2015 . THE POWER OF PARITY: HOW ADVANCING WOMEN’S EQUALITY CAN ADD $12 TRILLION TO GLOBAL GROWTH SEPTEMBER 2015 Jonathan Woetzel | Shanghai Anu Madgavkar | Mumbai Kweilin Ellingrud | Minneapolis Eric Labaye | Paris Sandrine Devillard | Paris Eric Kutcher | Silicon Valley James Manyika | San Francisco Richard Dobbs | London Mekala Krishnan | Stamford . PREFACE Gender inequality is a pressing global issue with huge ramifications not just for the lives and livelihoods of girls and women but, more generally, for human development, labor markets, productivity, GDP growth, and inequality. The challenge of inclusive growth is a theme that MGI has explored in many reports, and gender inequality is an important part of that picture. In this report, MGI undertakes what we believe may be the most comprehensive attempt to date to estimate the size of the economic potential from achieving gender parity and to map gender inequality. Using 15 indicators of gender equality in 95 countries, we have identified ten “impact zones”—concentrations of gender inequality that account for more than three-quarters of the women in the world affected by the gender gap—that we hope will help prioritize action. In addition, MGI has developed a Gender Parity Score, or GPS, that gives a view of what will help to close the gender gap. Our hope is that this analysis can point the way toward effective interventions and lead to new regional and global coalitions of policy makers and private-sector leaders.

This report builds on McKinsey & Company’s long-held interest in women’s issues in economics and business, notably our Women Matter research and participation in the UN Women Private Sector Leadership Advisory Council. This research was led by Jonathan Woetzel, a director of McKinsey and MGI based in Shanghai; Anu Madgavkar, an MGI senior fellow based in Mumbai; Kweilin Ellingrud, a partner based in Minneapolis; Eric Labaye, a director of McKinsey and MGI chairman based in Paris; Sandrine Devillard, a McKinsey director in Paris and author of McKinsey’s Women Matter research series; Eric Kutcher, a director in McKinsey’s Silicon Valley office; and Richard Dobbs and James Manyika, directors of McKinsey and MGI based in London and San Francisco, respectively. We thank McKinsey managing director Dominic Barton for his thoughtful guidance throughout this research effort. The team was led by Mekala Krishnan, a consultant based in Stamford, and comprised Maria Arellano (alumnus), Jaroslaw Bronowicki, Julia Hartnett, Morgan Hawley Ford, Shumi Jain, Shirley Ma, Giacomo Meille (alumnus), and Juliana Pflugfelder.

We would like to acknowledge the help and input of colleagues closely involved in this work, namely Rishi Arora, Gene Cargo, Shishir Gupta, Andres Ramirez Gutierrez, Vritika Jain, Xiujun Lillian Li, Jeongmin Seong, Vivien Singer, Soyoko Umeno, Roelof van Schalkwyk, and Iris Zhang. We are grateful to the academic advisers who helped shape this research and provided challenge and insights and guidance: Richard N. Cooper, Maurits C. Boas Professor of International Economics at Harvard University, and Laura Tyson, professor of business administration and economics and director of the Institute for Business and Social Impact, Haas Business and Public Policy Group, University of California at Berkeley. Special thanks go to three institutions that have made significant contributions to our understanding. We are grateful to the International Monetary Fund and, in particular, Rakesh Mohan, executive director, and Kalpana Kochhar, deputy director, Asia and Pacific Department; the International Finance Corporation and, in particular, Henriette Kolb, head of the Gender Secretariat; and the International Center for Research on Women, notably Sarah Degnan Kambou, president. There are many other individuals who contributed enormously to this work. We would like to thank Sajeda Amin, Population Council; Kim Azzarelli, co-founder, Seneca Women, and chair and cofounder, Cornell Avon Center for Women and Justice; Julie Ballington, policy adviser on political participation, UN Women; Joanna Barsh, former McKinsey director; Lina Benete, education policy specialist in Asia, UNESCO; Iris Bohnet, professor of public policy and director of the Women and Public Policy Program at the Harvard Kennedy School; Annabel Erulkar, director for Ethiopia, Population Council; Katherine Fritz, director, Global Health, International Center for Research on Women; Helene Gayle, CEO, McKinsey Social Initiatives and former president and CEO, CARE USA; Harriet Green, former CEO, Thomas Cook; Christophe Z. Guilmoto, director of demographic research, French Research Institute for Development; Katja Iversen, CEO, Women Deliver; Renée Joslyn, director, Girls and Women Integration at the Clinton Global Initiative; Jeni Klugman, senior adviser at the World Bank and fellow, Harvard Kennedy School’s Women and Public Policy Program; Jacquie Labatt, international photojournalist; Daniela Ligiero, vice president, Girls and Women Strategy, UN Foundation; Jessica Malter, strategic communications director, Women Deliver; Patience Marime-Ball, managing partner and CEO, .

Mara Ad-Venture Investments; Jennifer McCleary-Sills, director, Gender Violence and Rights, International Center for Research on Women; Terri McCullough, director, No Ceilings, Clinton Foundation; Phumzile MlamboNgcuka, under-secretary-general and executive director, UN Women; Stella Mukasa, regional director, Africa, International Center for Research on Women; Alyse Nelson, president and CEO, Vital Voices Global Partnership; Elizabeth Nyamayaro, senior advisor to the under-secretary-general of UN Women and head of HeforShe Campaign; Rohini Pande, consultant and team leader, World Bank; Saiqa Panjsheri, associate, child health, Abt Associates; Susan Papp, director of policy and advocacy, Women Deliver; Julien Pellaux, strategic planning and operations adviser, UN Women; Suzanne Petroni, senior director, Gender, Population, and Development, International Center for Research on Women; Alison Rowe, speechwriter and communications adviser, UN Women; Urvashi Sahni, nonresident fellow, Global Economy and Development, Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution, and founder and chief executive, Study Hall Educational Foundation; Pattie Sellers, assistant managing editor, Fortune magazine; Caroline Simard, research director, Clayman Institute for Gender Research, Stanford University; Rachel Tulchin, deputy director, No Ceilings, Clinton Foundation; Sher Verick, research fellow and senior employment specialist in the International Labour Organisation’s Decent Work Team for South Asia and New Delhi; Ravi Verma, regional director, Asia, International Center for Research on Women; and Melanne Verveer, director, Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security and co-founder, Seneca Women. We are also extremely grateful to some 50 other leaders from private-sector companies and social-sector organizations in India and the United States whose valuable insights and comments helped inform our deeper analysis of some aspects of gender inequality in these two countries, namely female economic empowerment and violence against women, respectively. We would like to thank many McKinsey colleagues for their input and industry expertise, especially Catherine Abi-Habib, Jonathan Ablett, Yasmine Aboudrar, Gassan Al-Kibsi, Manuela Artigas (alumnus), Cornelius Baur, Kalle Bengtsson, Subhashish Bhadra (alumnus), Lauren Brown, Penny Burtt (alumnus), Andres Cadena, Heloisa Callegaro, Raha Caramitru, Alberto Chaia, Wonsik Choi, Susan Colby, Georges Desvaux, Tarek Elmasry, David Fine, Tracy Francis, Anthony Goland, Andrew Grant, Anna Gressel-Bacharan, Rajat Gupta, Ashwin Hasyagar, Celia Huber, Vivian Hunt, Kristen Jennings, Beth Kessler, Charmhee Kim, Cecile Kossoff, Alejandro Krell, Eric Lamarre, Dennis Layton, Tony Lee, Acha Leke, John Lydon, Brendan Manquin (alumnus), Chiara Marcati, Kristen Mleczko, Lohini Moodley, Suraj Moraje, Matias Moral, Mona Mourshed, Olga Nissen, Maria Novales-Flamarique, Tracy Nowski, Francisco Ortega, Michael Phillips, Paula Ramos, Vivian Reifberg, Sahana Sarma, Doug Scott, Bernadette Sexton, Julia Silvis, Sven Smit, Yermolai Solzhenitsyn, Julia Sperling, Mark Staples, Claudia Süssmuth-Dyckerhoff, Lynn Taliento, Karen Tanner, Oliver Tonby, Jin Wang, Tim Welsh, Charlotte Werner, Lareina Yee, and Jin Yu. MGI’s operations team provided crucial support for this research. We would like to thank MGI senior editors Janet Bush and Lisa Renaud; Rebeca Robboy in external communications and media relations; Julie Philpot, editorial production manager; Marisa Carder and Margo Shimasaki, graphics specialists; and Deadra Henderson, manager of personnel and administration. We would also like to thank Mary Reddy, McKinsey editor and data visualization specialist, and Jason Leder, designer. We are grateful for all of the input we have received, but the final report is ours and any errors are our own. This report contributes to MGI’s mission to help business and policy leaders understand the forces transforming the global economy, identify strategic locations, and prepare for the next wave of long-term growth.

As with all MGI research, this work is independent and has not been commissioned or sponsored in any way by any business, government, or other institution, although it has benefited from the input and collaborations that we have mentioned. We welcome your emailed comments on the research at MGI@mckinsey.com. Richard Dobbs Director, McKinsey Global Institute London James Manyika Director, McKinsey Global Institute San Francisco Jonathan Woetzel Director, McKinsey Global Institute Shanghai September 2015 . © Getty Images . CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS In brief 29 Executive summary Page 1 1. The economic case for change Page 25 2. Three prerequisites for equality in work Page 41 Unpaid work 3. Mapping the gaps Page 59 49 4.

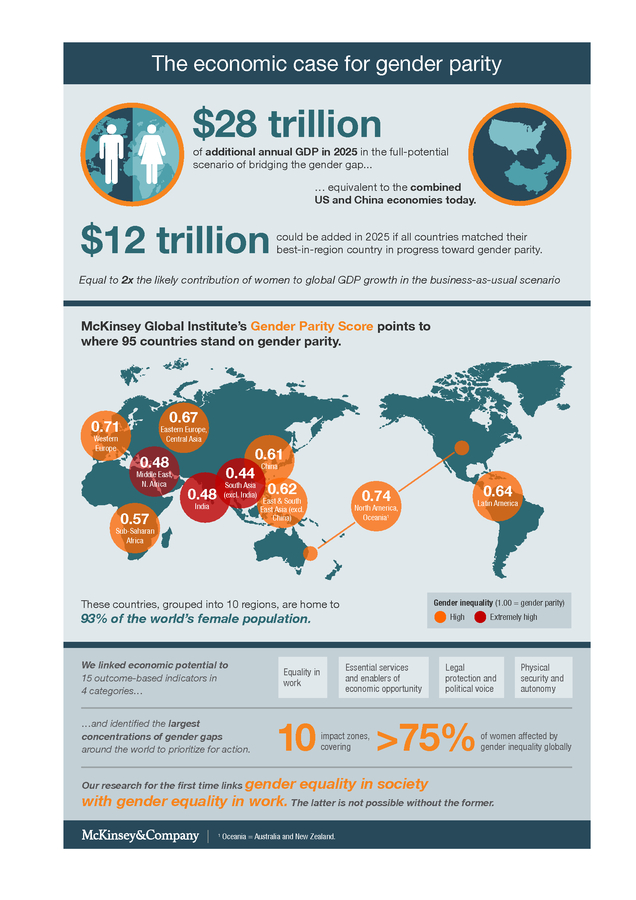

Agenda for action Page 81 Appendix Page 101 Bibliography Page 147 Girls’ education 50 Women and financial services . IN BRIEF THE POWER OF GLOBAL GENDER PARITY Narrowing the global gender gap in work would not only be equitable in the broadest sense but could double the contribution of women to global GDP growth between 2014 and 2025. Delivering that impact, however, will require tackling gender equality in society. ƒƒ MGI has mapped 15 gender equality indicators for 95 countries and finds that 40 of them have high or extremely high levels of gender inequality on at least half of the indicators. The indicators fall into four categories: equality in work, essential services and enablers of economic opportunity, legal protection and political voice, and physical security and autonomy. ƒƒ We consider a “full-potential” scenario in which women participate in the economy identically to men, and find that it would add up to $28 trillion, or 26 percent, to annual global GDP in 2025 compared with a business-as-usual scenario. This impact is roughly equivalent to the size of the combined US and Chinese economies today.

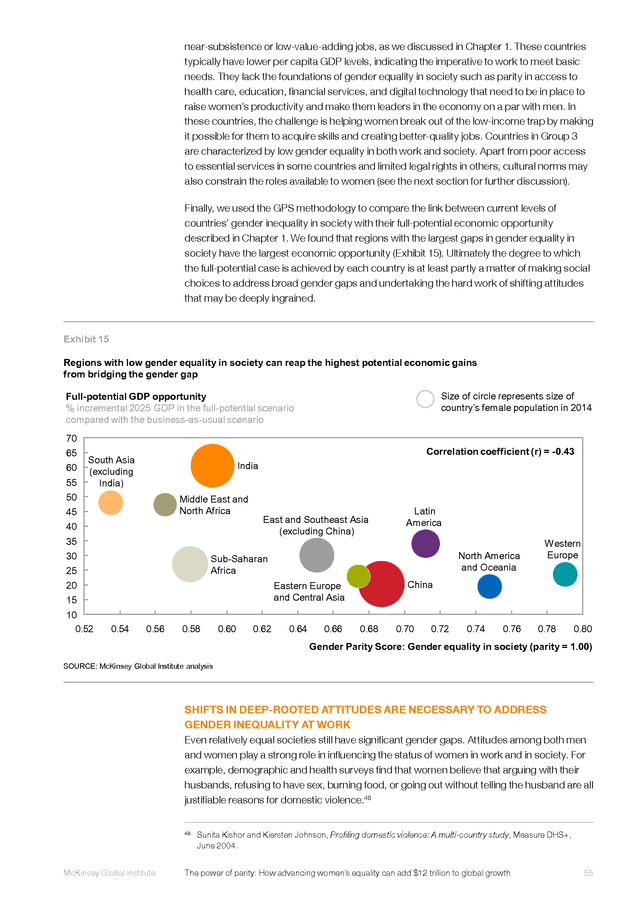

We also analyzed an alternative “best-in-region” scenario in which all countries match the rate of improvement of the best-performing country in their region. This would add as much as $12 trillion in annual 2025 GDP, equivalent in size to the current GDP of Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom combined, or twice the likely growth in global GDP contributed by female workers between 2014 and 2025 in a business-as-usual scenario. ƒƒ Both advanced and developing countries stand to gain. In 46 of the 95 countries analyzed, the bestin-region outcome could increase annual GDP in 2025 by more than 10 percent over the businessas-usual case, with the highest relative boost in India and Latin America. ƒƒ MGI’s new Gender Parity Score, or GPS, measures the distance each country has traveled toward gender parity, which is set at 1.00.

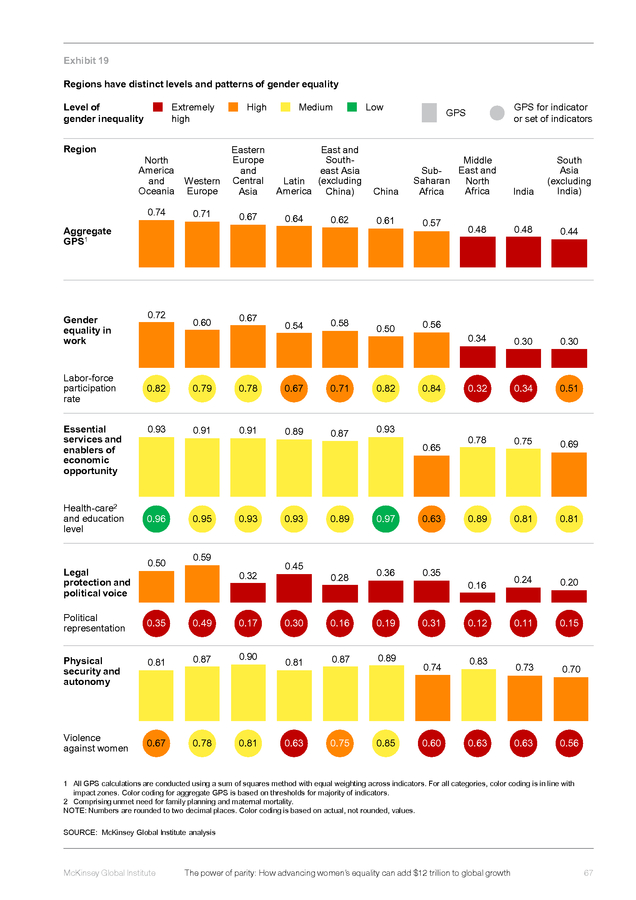

The regional GPS is lowest in South Asia (excluding India) at 0.44 and highest in North America and Oceania at 0.74. Using the GPS, MGI has established a strong link between gender equality in society, attitudes and beliefs about the role of women, and gender equality in work. The latter is not achievable without the former two elements.

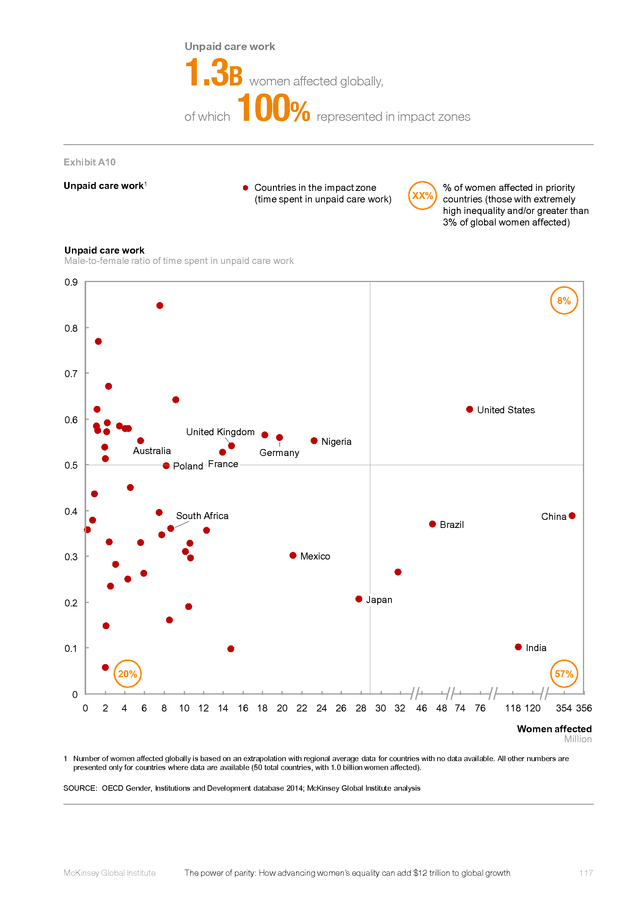

We found virtually no countries with high gender equality in society but low gender equality in work. Economic development enables countries to close gender gaps, but progress in four areas in particular— education level, financial and digital inclusion, legal protection, and unpaid care work—could help accelerate progress. ƒƒ MGI has identified ten “impact zones” (issue-region combinations) where effective action would move more than 75 percent of women affected by gender inequality globally closer to parity. The global impact zones are blocked economic potential, time spent in unpaid care work, fewer legal rights, political underrepresentation, and violence against women, globally pervasive issues.

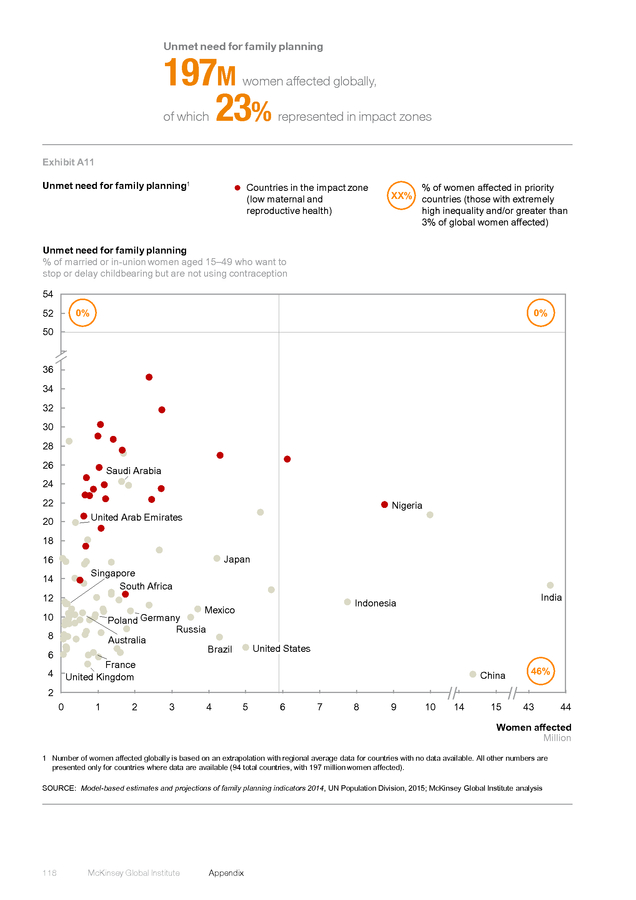

The regional impact zones are low labor-force participation in quality jobs, low maternal and reproductive health, unequal education levels, financial and digital exclusion, and girl-child vulnerability, concentrated in certain regions of the world. ƒƒ Six types of intervention are necessary to bridge the gender gap: financial incentives and support; technology and infrastructure; the creation of economic opportunity; capability building; advocacy and shaping attitudes; and laws, policies, and regulations. We identify some 75 potential interventions that could be evaluated and tailored to suit the social and economic context of each impact zone and country. ƒƒ Tackling gender inequality will require change within businesses as well as new coalitions. The private sector will need to play a more active role in concert with governments and non-governmental organizations—and companies could benefit both directly and indirectly by taking action. .

The economic case for gender parity $28 trillion of additional annual GDP in 2025 in the full-potential scenario of bridging the gender gap... … equivalent to the combined US and China economies today. $12 trillion could be added in 2025 if all countries matched their best-in-region country in progress toward gender parity. Equal to 2x the likely contribution of women to global GDP growth in the business-as-usual scenario McKinsey Global Institute’s Gender Parity Score points to where 95 countries stand on gender parity. 0.67 0.71 Eastern Europe, Central Asia Western Europe 0.48 Middle East, N. Africa 0.57 0.61 China 0.44 South Asia 0.62 0.48 (excl. India) East & South India 0.64 0.74 Latin America North America, Oceania¹ East Asia (excl. China) Sub-Saharan Africa Gender inequality (1.00 = gender parity) These countries, grouped into 10 regions, are home to 93% of the world’s female population. We linked economic potential to 15 outcome-based indicators in 4 categories… …and identiï¬ed the largest concentrations of gender gaps around the world to prioritize for action. High Essential services and enablers of economic opportunity Equality in work 10 Our research for the ï¬rst time links gender impact zones, covering Legal protection and political voice >75% equality in society Extremely high of women affected by gender inequality globally with gender equality in work. The latter is not possible without the former. ¹ Oceania = Australia and New Zealand. Physical security and autonomy .

© Getty Images viii McKinsey Global Institute  . EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Gender inequality is not only a pressing moral and social issue but also a critical economic challenge. If women—who account for half the world’s population—do not achieve their full economic potential, the global economy will suffer. While all types of inequality have economic consequences, in this research, we focus on the economic implications of lack of parity between men and women. Even after decades of progress toward making women equal partners with men in the economy and society, the gap between them remains large. We acknowledge that gender parity in economic outcomes (such as participation in the workforce or presence in leadership positions) is not necessarily a normative ideal as it involves human beings making personal choices about the lives they lead; we also recognize that men can be disadvantaged relative to women in some instances.

However, we believe that the world, including the private sector, would benefit by focusing on the large economic opportunity of improving parity between men and women. $12T TO $28T increase in GDP in 2025 through bridging the gender gap 40 OUT OF 95 countries have high or extremely high inequality on half or more of 15 indicators In this report, MGI explores the economic potential available if the global gender gap were to be closed. The research finds that, in a full-potential scenario in which women play an identical role in labor markets to men’s, as much as $28 trillion, or 26 percent, could be added to global annual GDP in 2025. This estimate is double that of other studies’ estimations, reflecting the fact that MGI has taken a more comprehensive view of gender inequality in work. Attaining parity in the world of work is not realistic in the short term.

Doing so would imply not only the reduction of formidable barriers and change in social attitudes but also personal choices about how to allocate time between domestic and market-based work. However, if all countries were to match the progress toward gender parity of the best performer in their region, it could produce a boost to annual global GDP of as much as $12 trillion in 2025. This would double the GDP growth contributed by female workers in the business-as-usualscenario. Our analysis maps 15 gender equality indicators for 95 countries that are home to 93 percent of the world’s female population and generate 97 percent of global GDP. It finds that 40 of the 95 countries have extremely high or high levels of inequality on half or more of the 15 indicators.

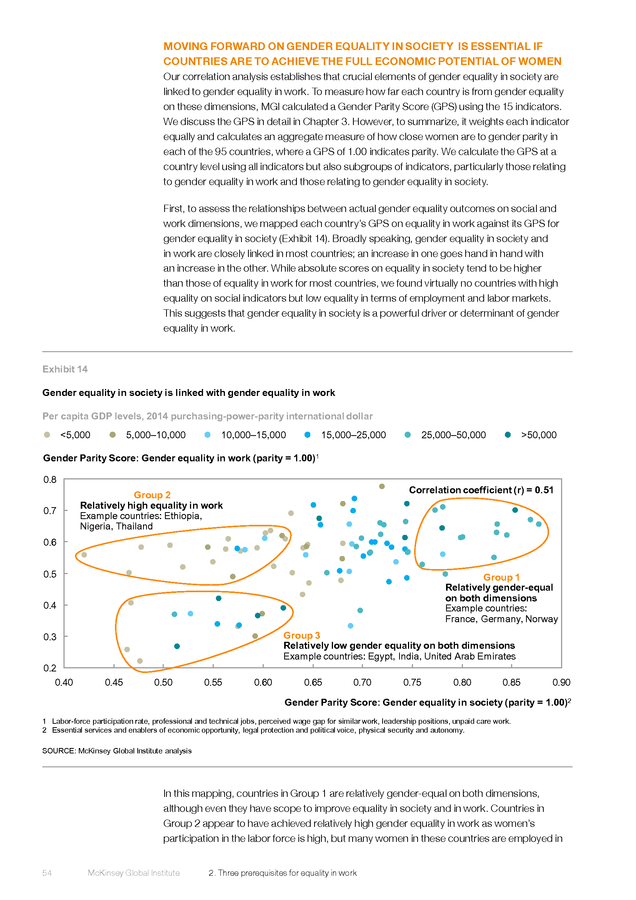

These indicators cover not only gender equality in work but also physical, social, political, and legal gender equality. We believe that this is the most comprehensive mapping of gender equality to date. And, for the first time, we have established a clear link between gender equality in society and in work through a new MGI tool called the Gender Parity Score, or GPS, which gives us a view of the distance that individual countries have traveled toward gender parity.

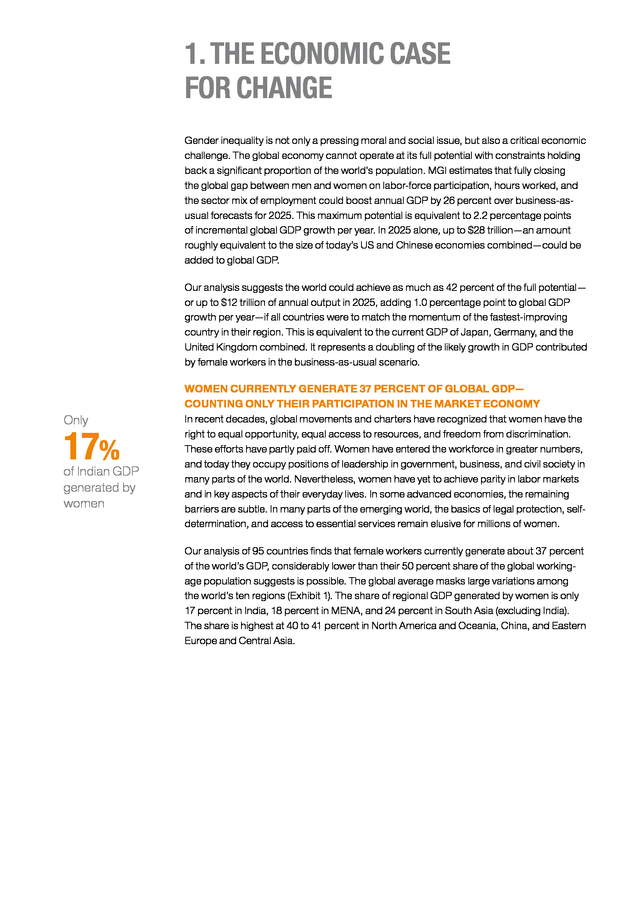

Realizing the economic prize of gender parity requires the world to address fundamental drivers of the gap in work equality, such as education, health, connectivity, security, and the role of women in unpaid work. To help policy makers, business leaders, and other stakeholders prioritize action in a global effort to close the gender gap, MGI has also identified ten impact zones of gender inequality. Across the impact zones, this report offers a six-part framework of types of intervention that are most likely to deliver change, and it discusses some of the factors that have made gender initiatives around the world successful, as well as the private sector’s opportunity to take the lead in defining initiatives. . FULLY CLOSING GENDER GAPS IN WORK WOULD ADD AS MUCH AS $28 TRILLION TO ANNUAL GDP IN 2025, WHILE ACHIEVING “BEST-IN-REGION” RATES OF PROGRESS WOULD ADD $12 TRILLION Women in the 95 countries analyzed in this research generate 37 percent of global GDP today despite accounting for 50 percent of the global working-age population. This global average contribution to GDP masks large variations among regions. The share of regional output generated by women is only 17 percent in India, 18 percent in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and 24 percent in South Asia (excluding India). In North America and Oceania, China, and Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the share is 40 to 41 percent. Women are half the world’s working-age population but generate only 37% of GDP. The lower representation of women in paid work is in contrast to their higher representation in unpaid work.

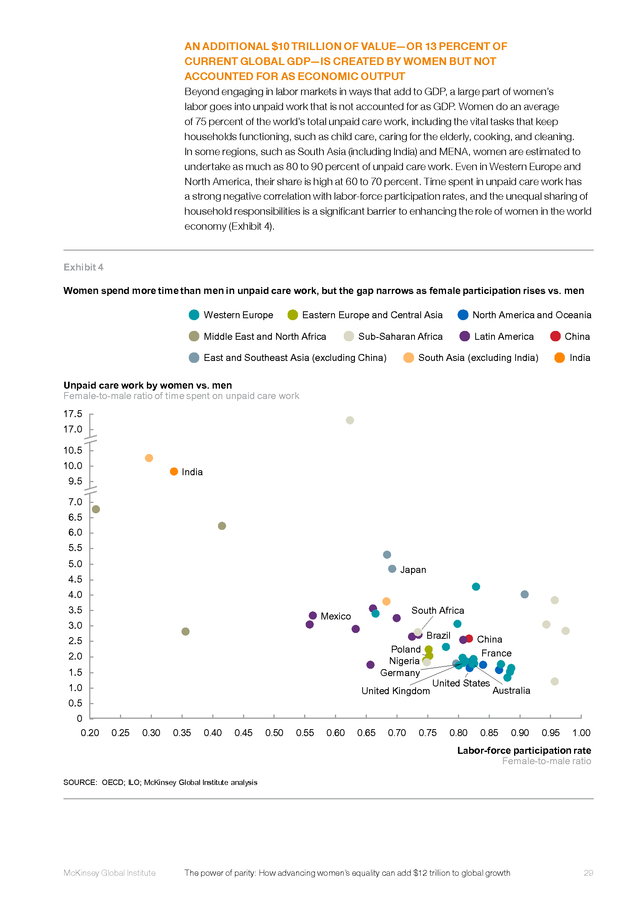

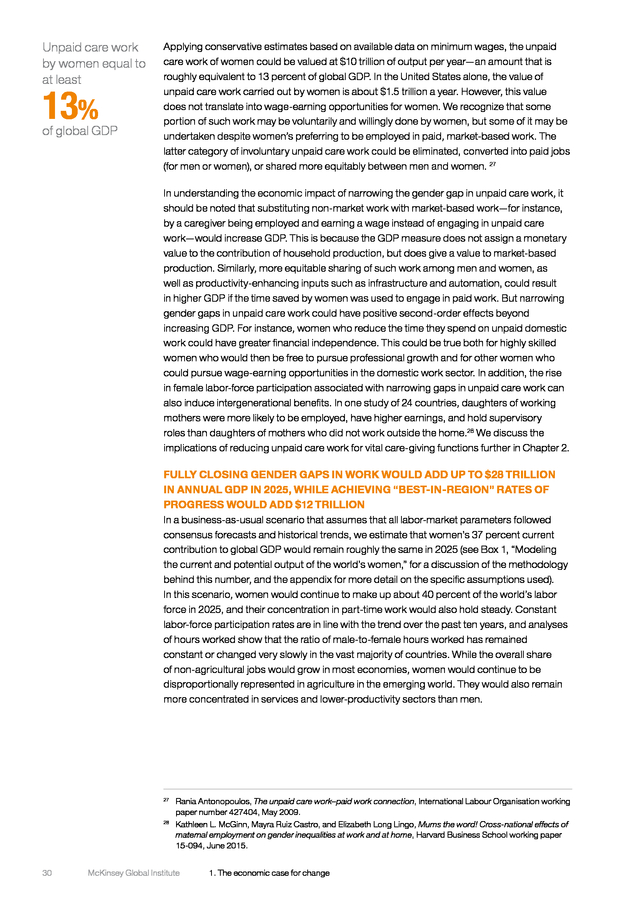

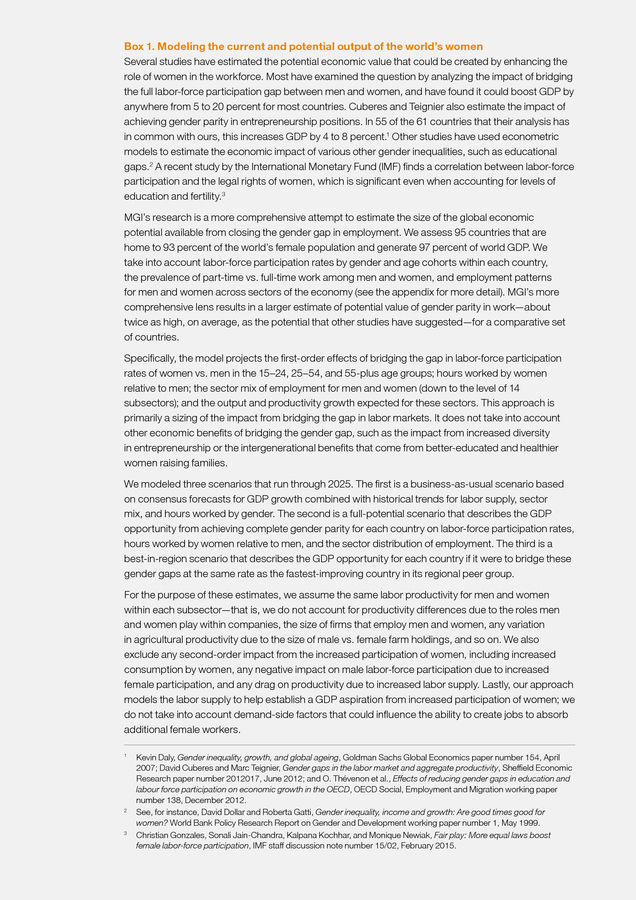

Seventy-five percent of the world’s total unpaid care is undertaken by women, including the vital tasks that keep households functioning such as child care, caring for the elderly, cooking, and cleaning. However, this contribution is not counted in traditional measures of GDP. Using conservative assumptions, we estimate that unpaid work being undertaken by women today amounts to as much as $10 trillion of output per year, roughly equivalent to 13 percent of global GDP. 75% of global unpaid work done by women MGI’s full-potential scenario assumes that women participate in the world of work to an identical extent as men—erasing the current gaps in labor-force participation rates, hours worked, and representation within each sector (which affects their productivity).

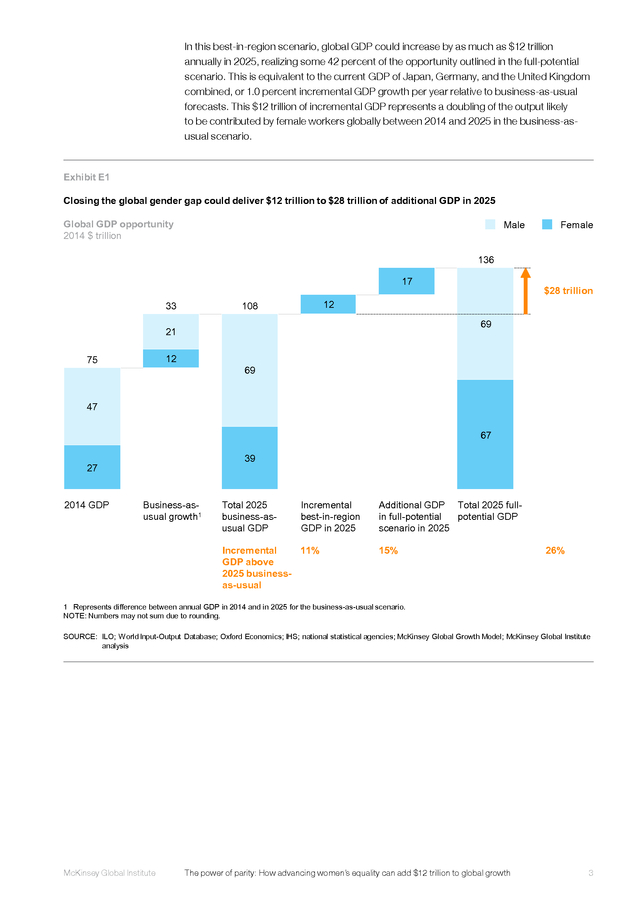

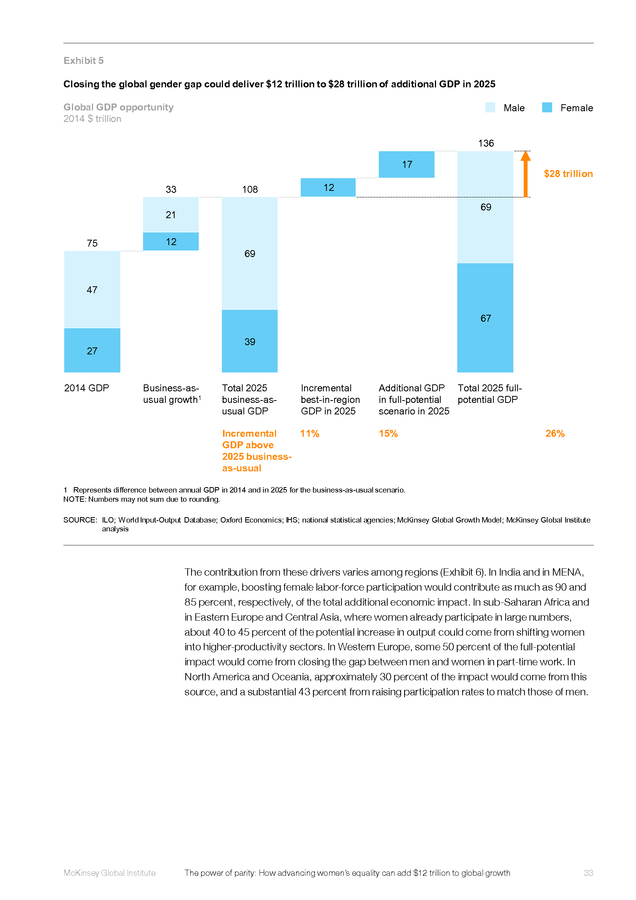

It represents the maximum economic impact that could be achieved from gender equality in labor markets. We find that the full-potential scenario could add as much as $28 trillion to annual GDP in 2025, raising global economic output by 26 percent over a business-as-usual scenario (Exhibit E1). This potential impact is roughly equivalent to the combined size of the economies of the United States and China today. The full-potential scenario sees the global average participation rate by women of prime working age rise from its current level of 64 percent to 95 percent.

However, this is unlikely to materialize within a decade; the barriers hindering women from participating on a par with men are unlikely to be fully addressed within that time frame, and, in any case, participation is ultimately a matter of personal choice. For these reasons, we also consider another scenario. MGI also assesses the size of the opportunity if each country were to bridge its gender gaps at the same rate as the fastest-improving country in its regional peer group. Countries in Western Europe, for instance, would close the gap in labor participation between men and women of prime working age by 1.5 percentage points a year, in line with the experience of Spain between 2003 and 2013.

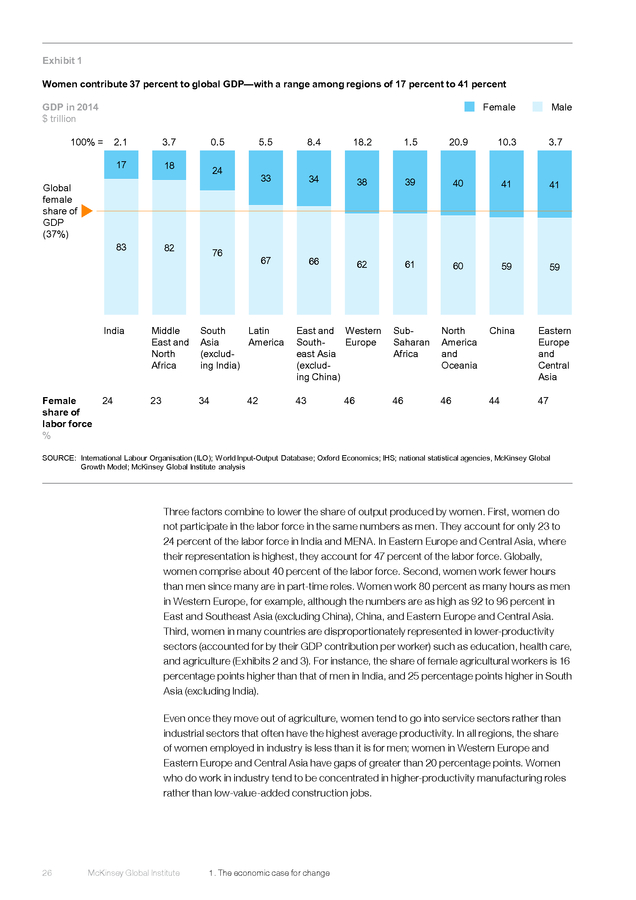

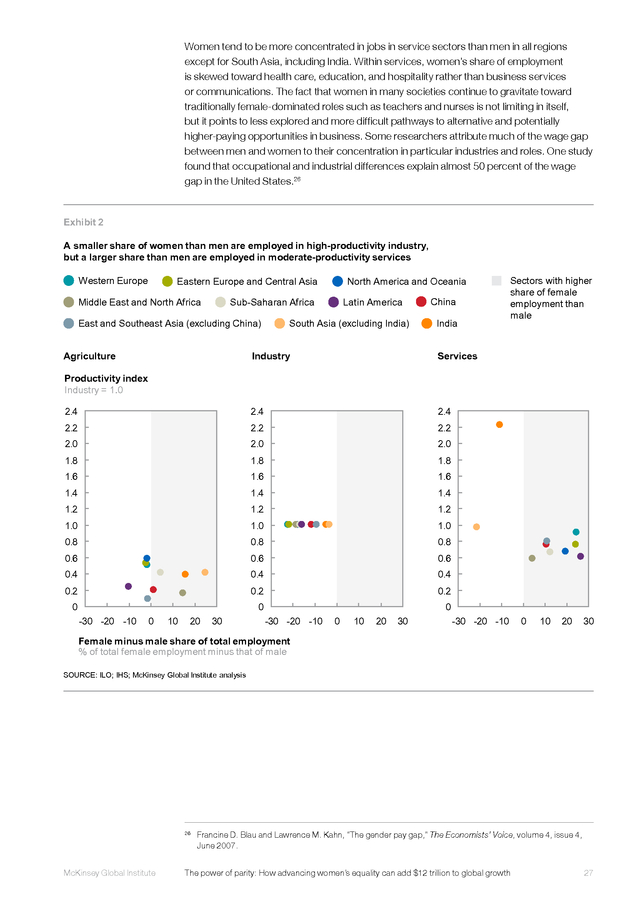

Countries in Latin America would do so at Chile’s annual rate of 1.9 percentage points, while countries in East and Southeast Asia would do so at Singapore’s rate of 1.1 percentage points a year. At these rates of progress, global average labor-force participation rates for this age cohort would reach 74 percent by 2025, or about ten percentage points higher than at present. 2 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary . In this best-in-region scenario, global GDP could increase by as much as $12 trillion annually in 2025, realizing some 42 percent of the opportunity outlined in the full-potential scenario. This is equivalent to the current GDP of Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom combined, or 1.0 percent incremental GDP growth per year relative to business-as-usual forecasts. This $12 trillion of incremental GDP represents a doubling of the output likely to be contributed by female workers globally between 2014 and 2025 in the business-asusual scenario. Exhibit E1 Closing the global gender gap could deliver $12 trillion to $28 trillion of additional GDP in 2025 Global GDP opportunity 2014 $ trillion Male Female 136 17 33 108 69 21 12 75 $28 trillion 12 69 47 67 39 27 2014 GDP Business-asusual growth1 Total 2025 business-asusual GDP Incremental best-in-region GDP in 2025 Incremental 11% GDP above 2025 businessas-usual Additional GDP Total 2025 fullin full-potential potential GDP scenario in 2025 15% 26% 1 Represents difference between annual GDP in 2014 and in 2025 for the business-as-usual scenario. NOTE: Numbers may not sum due to rounding. SOURCE: ILO; World Input-Output Database; Oxford Economics; IHS; national statistical agencies; McKinsey Global Growth Model; McKinsey Global Institute analysis REPEATS as x5 Gender gap ES 0929 mc McKinsey Global Institute The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth 3 . MGI’s estimate of the maximum gender parity prize in the full-potential scenario is twice as large as the average of several other estimates.1 Many of these studies focus exclusively on labor-force participation, but we assess the potential impact from closing the gap on two other dimensions as well. First, women do not participate in the labor force in the same numbers as men; increasing the labor-force participation of women accounts for 54 percent of potential incremental GDP. Second, women work fewer hours than men (in the labor force) because many are in part-time jobs; this could be driven partly by choice and partly by their inability to do fulltime work given family- and home-based responsibilities. Closing this gap would generate 23 percent of the GDP opportunity. Third, women are disproportionately represented in lower-productivity sectors such as agriculture and insufficiently represented in higherproductivity sectors such as business services.

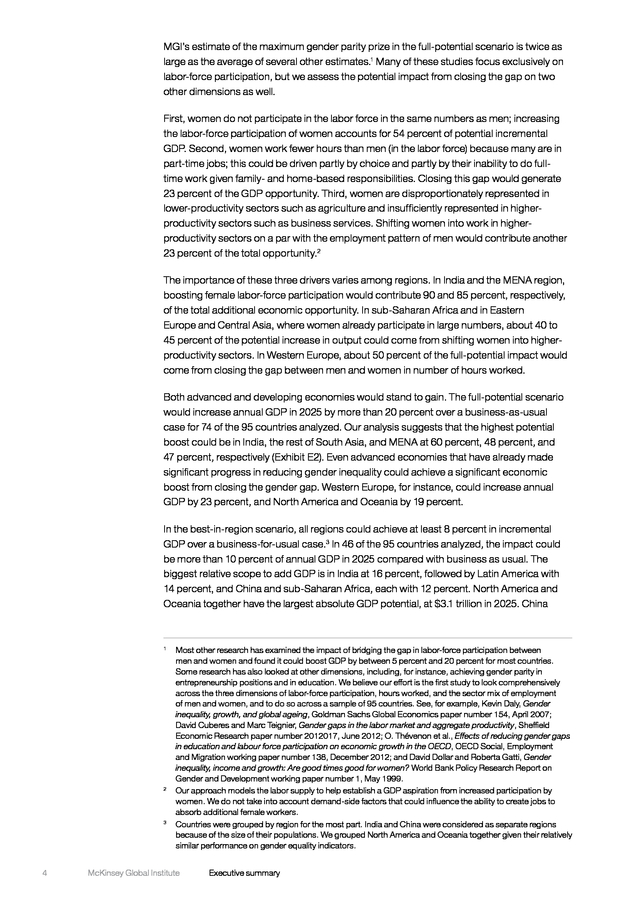

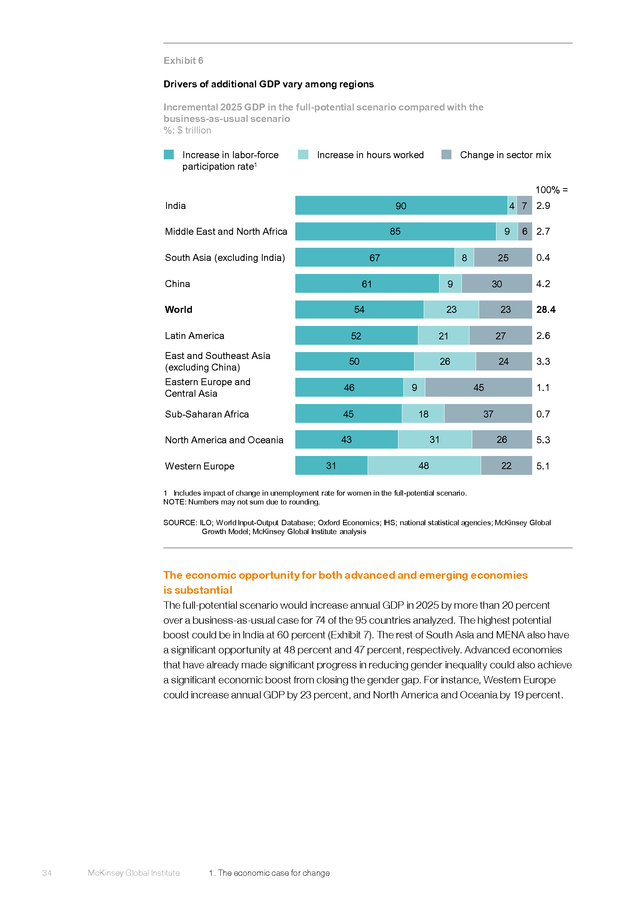

Shifting women into work in higherproductivity sectors on a par with the employment pattern of men would contribute another 23 percent of the total opportunity.2 The importance of these three drivers varies among regions. In India and the MENA region, boosting female labor-force participation would contribute 90 and 85 percent, respectively, of the total additional economic opportunity. In sub-Saharan Africa and in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where women already participate in large numbers, about 40 to 45 percent of the potential increase in output could come from shifting women into higherproductivity sectors.

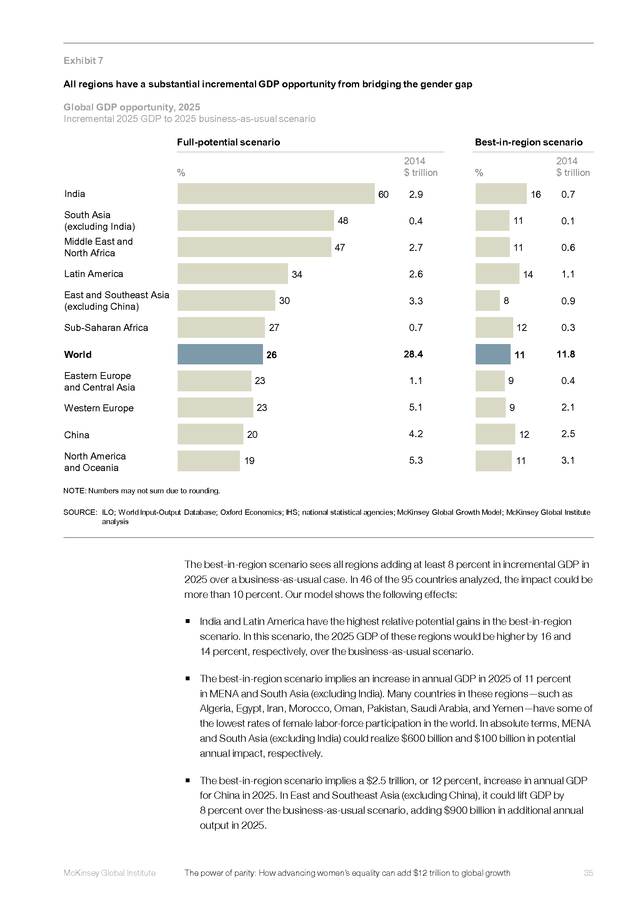

In Western Europe, about 50 percent of the full-potential impact would come from closing the gap between men and women in number of hours worked. Both advanced and developing economies would stand to gain. The full-potential scenario would increase annual GDP in 2025 by more than 20 percent over a business-as-usual case for 74 of the 95 countries analyzed. Our analysis suggests that the highest potential boost could be in India, the rest of South Asia, and MENA at 60 percent, 48 percent, and 47 percent, respectively (Exhibit E2).

Even advanced economies that have already made significant progress in reducing gender inequality could achieve a significant economic boost from closing the gender gap. Western Europe, for instance, could increase annual GDP by 23 percent, and North America and Oceania by 19 percent. In the best-in-region scenario, all regions could achieve at least 8 percent in incremental GDP over a business-for-usual case.3 In 46 of the 95 countries analyzed, the impact could be more than 10 percent of annual GDP in 2025 compared with business as usual. The biggest relative scope to add GDP is in India at 16 percent, followed by Latin America with 14 percent, and China and sub-Saharan Africa, each with 12 percent.

North America and Oceania together have the largest absolute GDP potential, at $3.1 trillion in 2025. China Most other research has examined the impact of bridging the gap in labor-force participation between men and women and found it could boost GDP by between 5 percent and 20 percent for most countries. Some research has also looked at other dimensions, including, for instance, achieving gender parity in entrepreneurship positions and in education. We believe our effort is the first study to look comprehensively across the three dimensions of labor-force participation, hours worked, and the sector mix of employment of men and women, and to do so across a sample of 95 countries.

See, for example, Kevin Daly, Gender inequality, growth, and global ageing, Goldman Sachs Global Economics paper number 154, April 2007; David Cuberes and Marc Teignier, Gender gaps in the labor market and aggregate productivity, Sheffield Economic Research paper number 2012017, June 2012; O. Thévenon et al., Effects of reducing gender gaps in education and labour force participation on economic growth in the OECD, OECD Social, Employment and Migration working paper number 138, December 2012; and David Dollar and Roberta Gatti, Gender inequality, income and growth: Are good times good for women? World Bank Policy Research Report on Gender and Development working paper number 1, May 1999. 2 Our approach models the labor supply to help establish a GDP aspiration from increased participation by women. We do not take into account demand-side factors that could influence the ability to create jobs to absorb additional female workers. 3 Countries were grouped by region for the most part.

India and China were considered as separate regions because of the size of their populations. We grouped North America and Oceania together given their relatively similar performance on gender equality indicators. 1 4 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary . comes in next at $2.5 trillion, and Western Europe follows with $2.1 trillion of potential GDP increase in 2025. Exhibit E2 All regions have a substantial incremental GDP opportunity from bridging the gender gap Global GDP opportunity, 2025 Incremental 2025 GDP to 2025 business-as-usual scenario Full-potential scenario Best-in-region scenario 2014 $ trillion % India 60 South Asia (excluding India) 48 Middle East and North Africa 47 Latin America 34 East and Southeast Asia (excluding China) 30 2014 $ trillion % 2.9 16 0.7 0.4 11 0.1 2.7 11 0.6 2.6 3.3 14 8 1.1 0.9 Sub-Saharan Africa 27 0.7 12 0.3 World 26 28.4 11 11.8 Eastern Europe and Central Asia 23 1.1 9 0.4 Western Europe 23 5.1 9 2.1 20 China North America and Oceania 19 4.2 5.3 12 11 2.5 3.1 NOTE: Numbers may not sum due to rounding. SOURCE: ILO; World Input-Output Database; Oxford Economics; IHS; national statistical agencies; McKinsey Global Growth Model; McKinsey Global Institute analysis 240M These estimates assume that there is no decline in male participation in response to the rising number of women in the workforce. Between 1980 and 2010, across 60 countries, the rate of labor-force participation for women of prime working age rose by 19.7 percentage points (based on a simple average), while the corresponding male labor-force participation rate fell by 1.5 percentage points. The gains from higher female participation were negated to a very small extent by men withdrawing from the workforce. Assuming the male participation rate does not shrink, the best-in-region scenario would increase the world’s employed labor force by some 240 million workers in 2025 over the business-asusual scenario. workers potentially added through REPEATS higher female participation as x7 The entry of more women into the labor force would be of significant benefit to countries with aging populations that face pressure on their pools of labor and therefore, potentially, on their GDP growth.

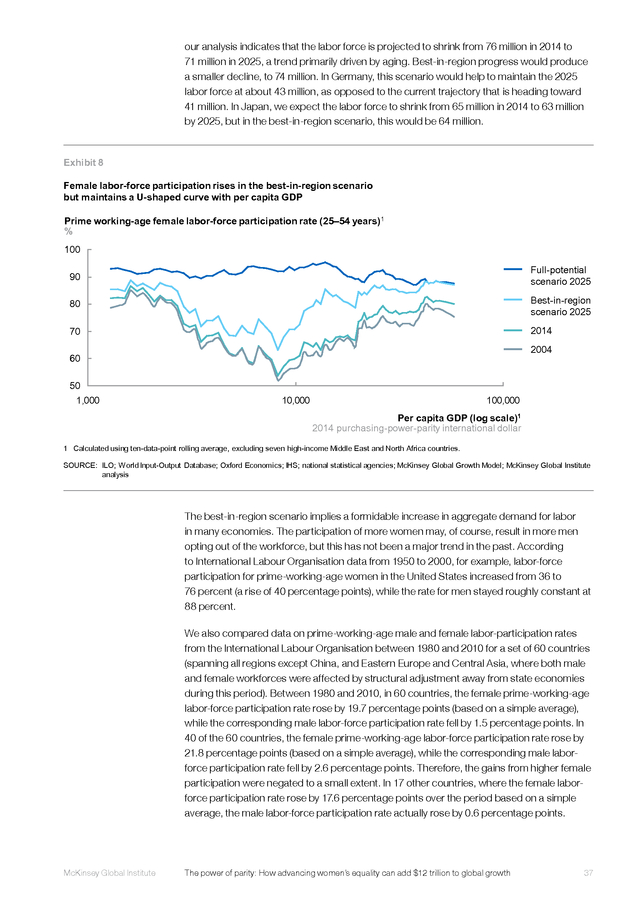

In Russia, for instance, our analysis indicates that the labor force is projected to shrink from 76 million in 2014 to 71 million in 2025, primarily due to aging. The best-in-region scenario would produce a milder decline to 74 million. In Japan, we expect the labor force to shrink to 63 million by 2025 from 65 million in 2014; in a best-in-region scenario, the labor force would be 64 million. McKinsey Global Institute The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth 5 .

Beyond narrowing the gap in labor-force participation, the best-in-region scenario assumes that the gap between average female and male labor productivity narrows from 13 percent to 3 percent within a decade as more women shift out of agriculture and into higher productivity industry and service sector jobs. In this scenario, the share of global employment in agriculture would shrink by a further 2.0 percentage points over the 5.6 percentage point decline likely in the business-as-usual scenario, with larger shifts in subSaharan Africa and South Asia (excluding India). To maintain the global share of agricultural GDP at about 4.5 percent in 2025, as in the business-as-usual scenario, agricultural productivity would need to rise. Globally, we estimate that agricultural productivity growth would need to increase from 4.4 percent per year in the business-as-usual scenario to 4.9 percent in the best-in-region scenario. Achieving this scenario would require investment—including productivity-boosting investment in an agricultural sector shedding workers, and job-creating investment in the industrial and services sectors that are absorbing additional workers.

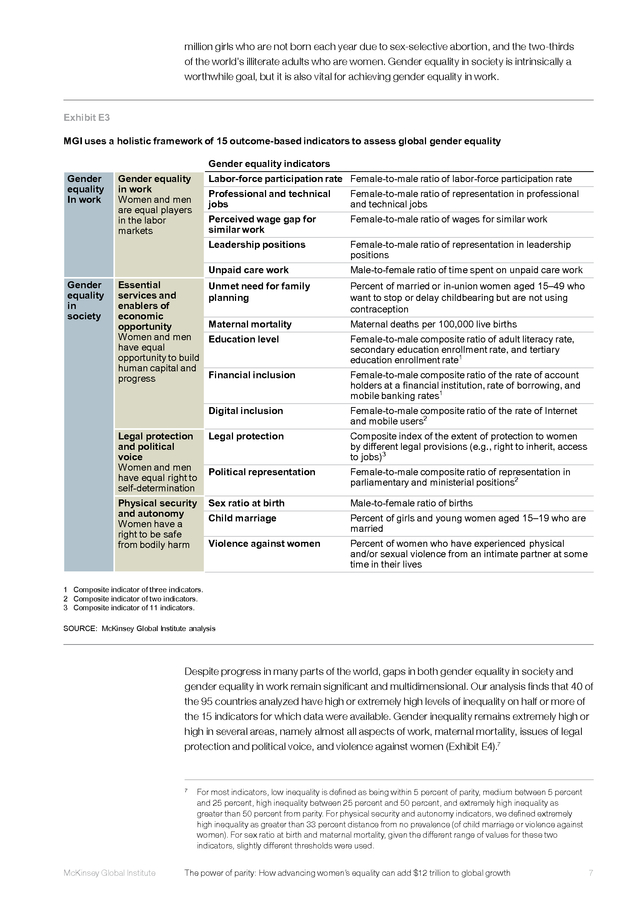

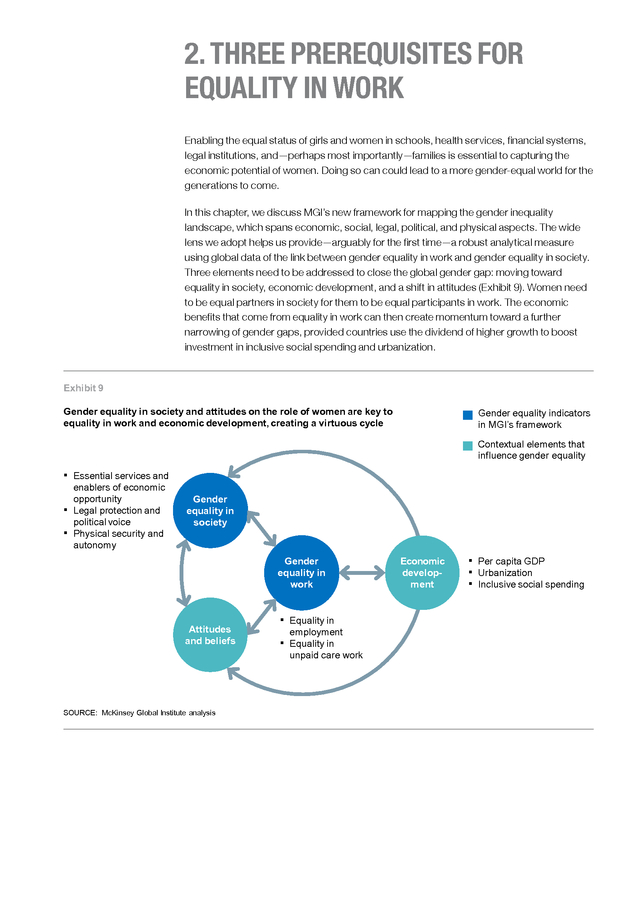

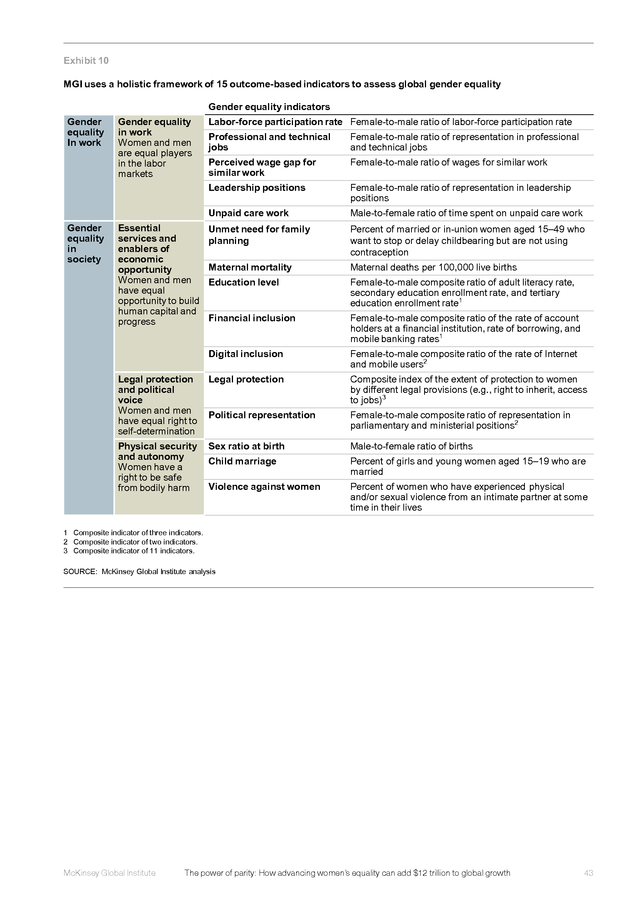

For example, MGI estimates that the incremental investment required in 2025 could be $3 trillion, or roughly 11 percent higher than in the business-as-usual scenario.4 Governments would also need to address barriers inhibiting productive job creation and human capital formation—not just for women, but for their overall economies.5 THREE ELEMENTS—GENDER EQUALITY IN SOCIETY, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, AND A SHIFT IN ATTITUDES—ARE NEEDED TO ACHIEVE THE FULL POTENTIAL OF WOMEN IN THE WORKFORCE There is a compelling—and potentially achievable—case for the world to bridge gender gaps in work equality. Three elements are essential for achieving the full potential of gender parity: gender equality in society, economic development, and a shift in attitudes. Gender inequality at work is mirrored by gender inequality in society The economic size of the gender gap is only part of a larger divide that affects society. Therefore, any analysis of gender inequality and how to tackle it needs to include both economic and social aspects. With this in mind, MGI’s gender equality framework has 15 indicators on four dimensions (Exhibit E3).6 1M+ girls not born each year due to sex-selective abortion The first dimension is gender equality in work, which includes the ability of women to engage in paid work and to share unpaid work more equitably with men, to have the skills and opportunity to perform higher-productivity jobs, and to occupy leading positions in the economy.

This dimension is driven by the choices men and women make about the lives they lead and the work they do. The next three dimensions—essential services and enablers of economic opportunity, legal protection and political voice, and physical security and autonomy—relate to fundamentals of social equality. They are necessary to ensure that women (and men) have the opportunity to build human capital and the resources and ability to live a life of their own making.

We refer to these three dimensions collectively as gender equality in society, a term that embraces issues that are important from a moral or humanitarian standpoint and affect many women—for instance, the more than one Calculated based on historical trend analysis of the relationship between investment and GDP for each region, using data from IHS. 5 Several MGI country studies have examined the question of what measures can stimulate investment and job creation for inclusive growth; see MGI’s reports on Africa, Brazil, Europe, India, and Nigeria, all downloadable for free at www.mckinsey.com/mgi. Also see Global growth: Can productivity save the day in an aging world? McKinsey Global Institute, January 2015. 6 This is the most comprehensive mapping of gender across broad dimensions and a broad range of countries that we are aware of. For instance, the OECD’s Social Institutions and Gender Index focuses primarily on social institutions such as discriminatory family codes, restricted physical integrity, and rights to inheritance. The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index looks at economic and political outcomes, and the development of human capital through education and health, but not at legal, financial, and digital enablers of economic opportunity or at violence.

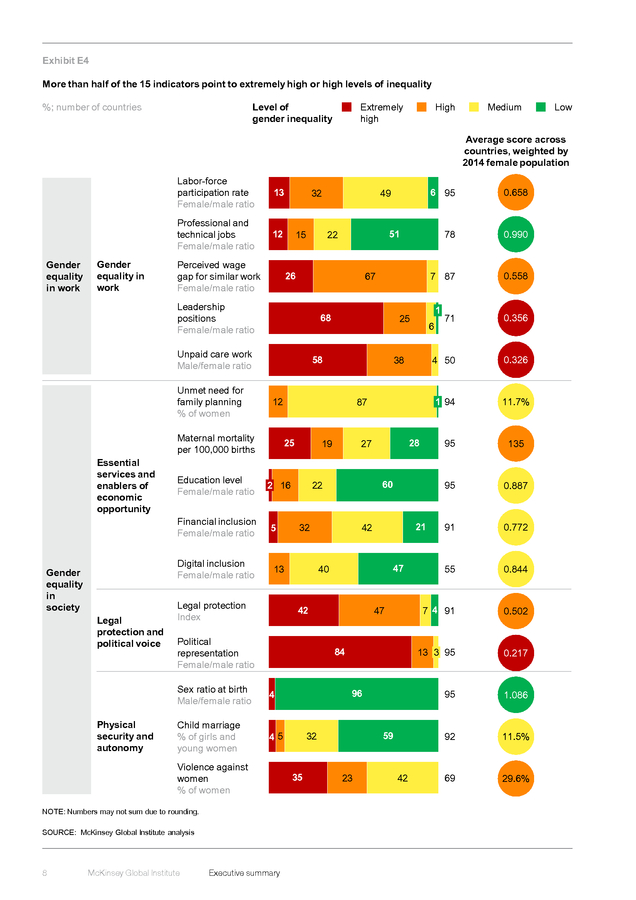

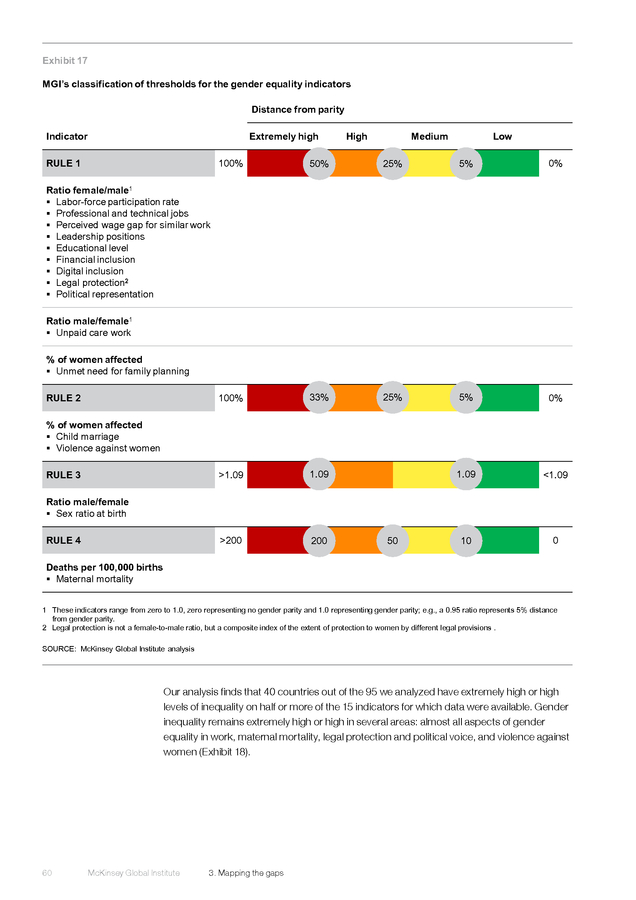

The European Union’s Gender Equality Index covers only the countries of the EU. 4 6 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary . million girls who are not born each year due to sex-selective abortion, and the two-thirds of the world’s illiterate adults who are women. Gender equality in society is intrinsically a worthwhile goal, but it is also vital for achieving gender equality in work. Exhibit E3 MGI uses a holistic framework of 15 outcome-based indicators to assess global gender equality Gender equality indicators Gender equality In work Gender equality in work Women and men are equal players in the labor markets Labor-force participation rate Female-to-male ratio of labor-force participation rate Physical security and autonomy Women have a right to be safe from bodily harm Female-to-male ratio of wages for similar work Female-to-male ratio of representation in leadership positions Male-to-female ratio of time spent on unpaid care work Unmet need for family planning Percent of married or in-union women aged 15–49 who want to stop or delay childbearing but are not using contraception Maternal mortality Maternal deaths per 100,000 live births Education level Female-to-male composite ratio of adult literacy rate, secondary education enrollment rate, and tertiary education enrollment rate1 Financial inclusion Female-to-male composite ratio of the rate of account holders at a financial institution, rate of borrowing, and mobile banking rates1 Digital inclusion Legal protection and political voice Women and men have equal right to self-determination Perceived wage gap for similar work Unpaid care work Essential services and enablers of economic opportunity Women and men have equal opportunity to build human capital and progress Female-to-male ratio of representation in professional and technical jobs Leadership positions Gender equality in society Professional and technical jobs Female-to-male composite ratio of the rate of Internet and mobile users2 Legal protection Composite index of the extent of protection to women by different legal provisions (e.g., right to inherit, access to jobs)3 Political representation Female-to-male composite ratio of representation in parliamentary and ministerial positions2 Sex ratio at birth Male-to-female ratio of births Child marriage Percent of girls and young women aged 15–19 who are married Violence against women Percent of women who have experienced physical and/or sexual violence from an intimate partner at some time in their lives 1 Composite indicator of three indicators. 2 Composite indicator of two indicators. 3 Composite indicator of 11 indicators. SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis Despite progress of the world, gaps in both gender equality in society and REPEATS as x10inin many partssignificant and multidimensional. Our analysis finds that 40 of gender equality work remain the 95 countries analyzed have high or extremely high levels of inequality on half or more of the 15 indicators for which data were available. Gender inequality remains extremely high or high in several areas, namely almost all aspects of work, maternal mortality, issues of legal protection and political voice, and violence against women (Exhibit E4).7 7 McKinsey Global Institute For most indicators, low inequality is defined as being within 5 percent of parity, medium between 5 percent and 25 percent, high inequality between 25 percent and 50 percent, and extremely high inequality as greater than 50 percent from parity.

For physical security and autonomy indicators, we defined extremely high inequality as greater than 33 percent distance from no prevalence (of child marriage or violence against women). For sex ratio at birth and maternal mortality, given the different range of values for these two indicators, slightly different thresholds were used. The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth 7 . Exhibit E4 More than half of the 15 indicators point to extremely high or high levels of inequality Level of gender inequality %; number of countries Extremely high High Medium Low Average score across countries, weighted by 2014 female population Labor-force participation rate Female/male ratio Professional and technical jobs Female/male ratio Gender equality in work Gender equality in work 13 12 Perceived wage gap for similar work Female/male ratio 26 Essential services and enablers of economic opportunity Gender equality in society Education level Female/male ratio Financial inclusion Female/male ratio Digital inclusion Female/male ratio Legal protection and political voice 5 Legal protection Index 45 Violence against women % of women NOTE: Numbers may not sum due to rounding. SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis 8 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary 0.887 91 0.772 55 0.844 0.502 13 3 95 0.217 95 1.086 92 47 96 59 32 35 135 7 4 91 47 84 Child marriage % of girls and young women 95 11.5% 69 29.6% 21 40 4 11.7% 95 42 32 42 Sex ratio at birth Male/female ratio Physical security and autonomy 28 60 22 Political representation Female/male ratio 0.326 1 94 27 19 13 0.356 4 50 87 2 16 71 6 38 12 25 0.558 1 25 58 Maternal mortality per 100,000 births 0.990 7 87 68 Unpaid care work Male/female ratio Unmet need for family planning % of women 78 67 Leadership positions Female/male ratio 0.658 51 22 15 6 95 49 32 23 42 . ƒƒ Equality in work. Gender gaps in the world of work remain high or extremely high on four out of five indicators. Women make up 40 percent of the global labor force despite a 50 percent share of the working-age population and a 46 to 47 percent share of the labor force in regions such as Western Europe, North America and Oceania, and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. There are extremely high or high gaps in 21 of the 78 countries analyzed on the share of women vs.

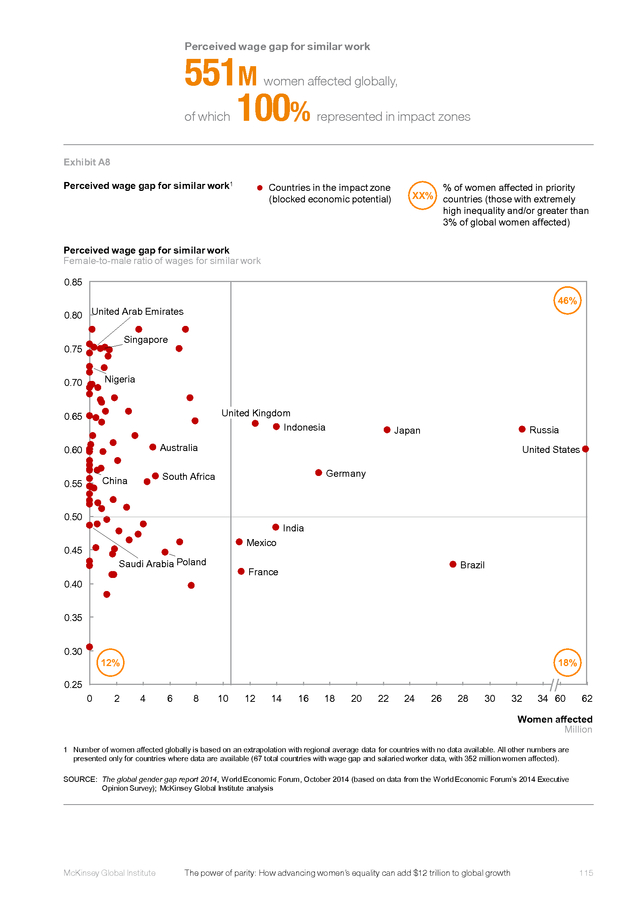

men in professional and technical jobs. Perceived wage disparity for similar work remains a significant issue, although this gender gap is difficult to prove conclusively. World Economic Forum surveys of business leaders find a widespread perception that women earn less than men for equivalent work in all 87 countries in our data set for which data are available.

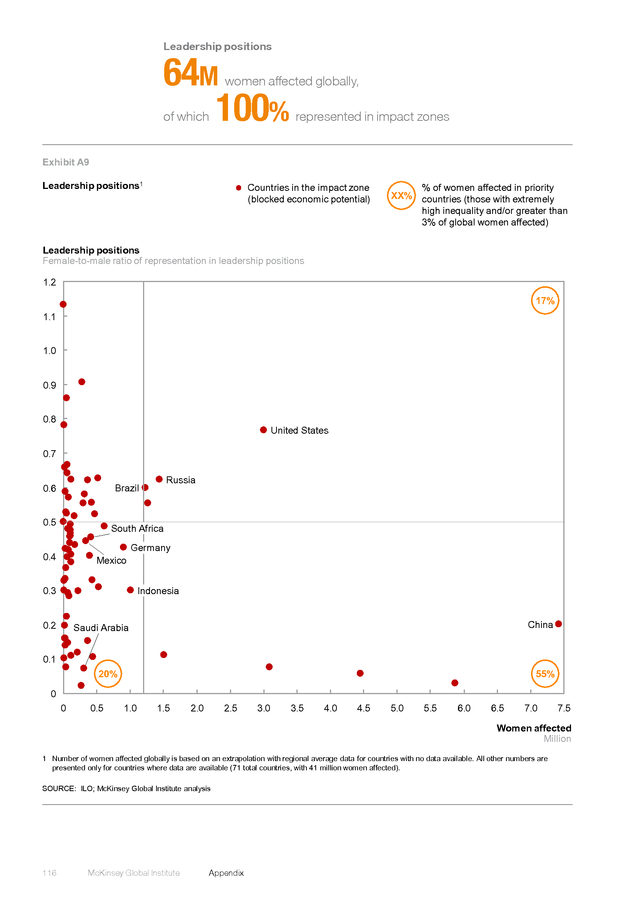

International Labour Organisation data find that men are almost three times as likely as women to hold leadership positions as legislators, senior officials, and managers. Women spend three times as many hours in unpaid care work as men; in India and Pakistan, women spend nearly ten times as many hours as men in such activity. ƒƒ Essential services and enablers of economic opportunity. We assess this dimension in terms of women’s access to health care (represented by reproductive and maternal health), education, financial services, and digital connectivity.

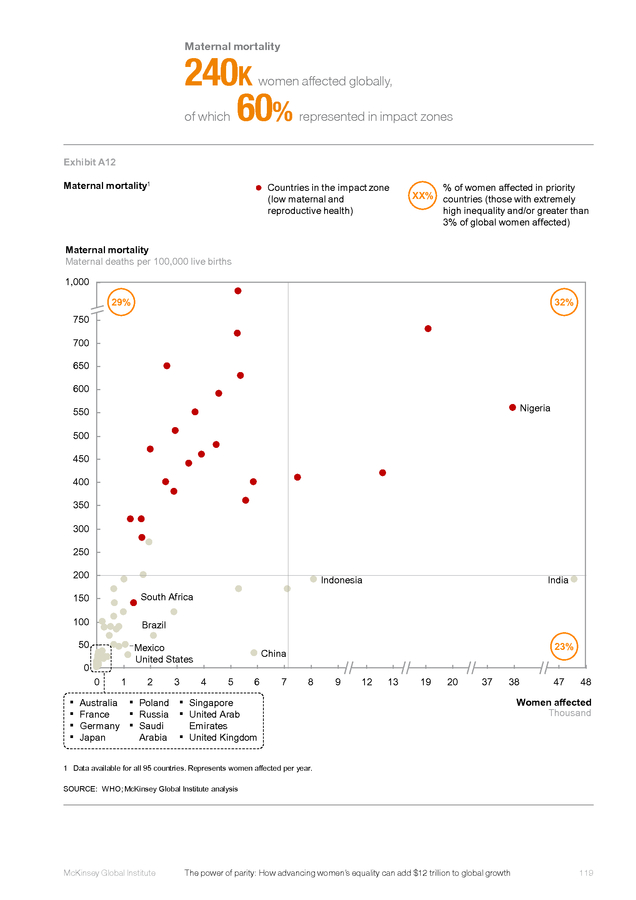

Unmet need for family planning is a medium inequality issue in 82 of the 94 countries analyzed. 197 million women globally who want to stop or delay having children are nevertheless not using contraception. Maternal health has improved in many parts of the world, but maternal mortality is a source of extremely high or high inequality in 42 countries in our set of 95.

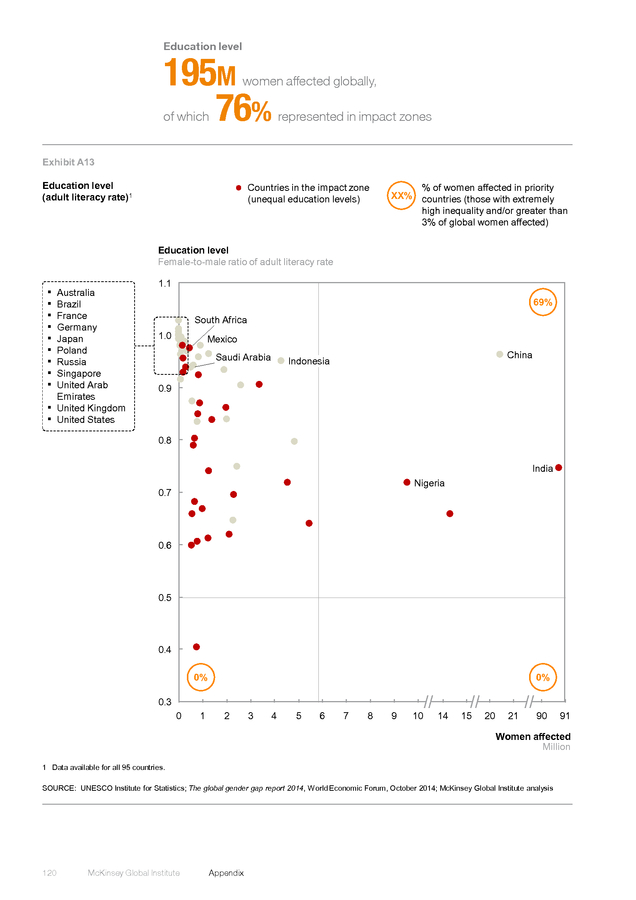

The gender gap in education has narrowed in many regions, but women still attain less than 75 percent of the educational levels of men in 17 of the 95 countries studied. Globally, some 195 million fewer adult women than men are literate. The world’s women still have only 77 percent of the access that men have to financial services, on average, and only 84 percent of the access of men to the Internet and mobile phones. 22 women in ministerial and parliamentary roles for every 100 men 30% of women have been victims of violence from an intimate partner ƒƒ Legal protection and political voice. Legal protection for women has improved, but there is further to go.

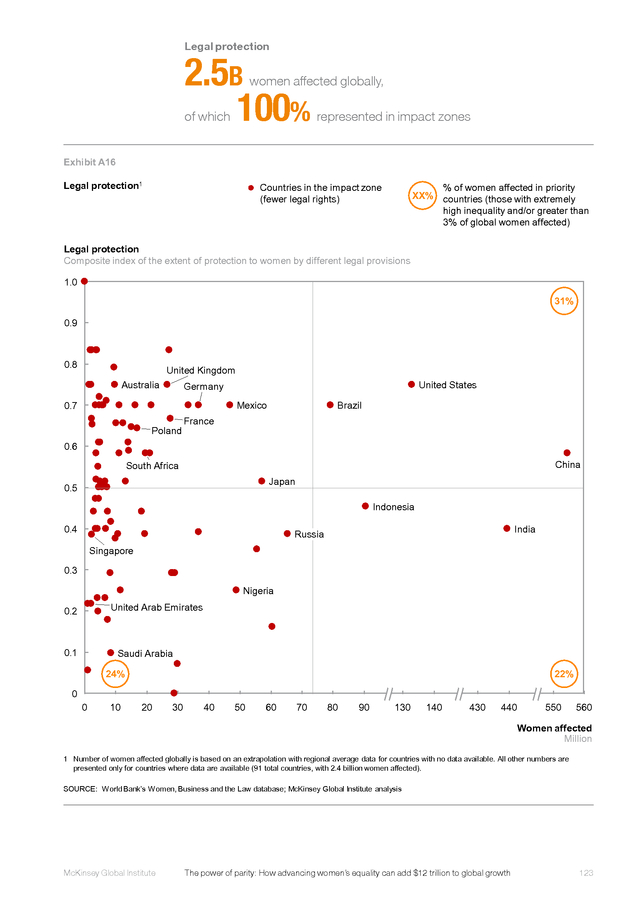

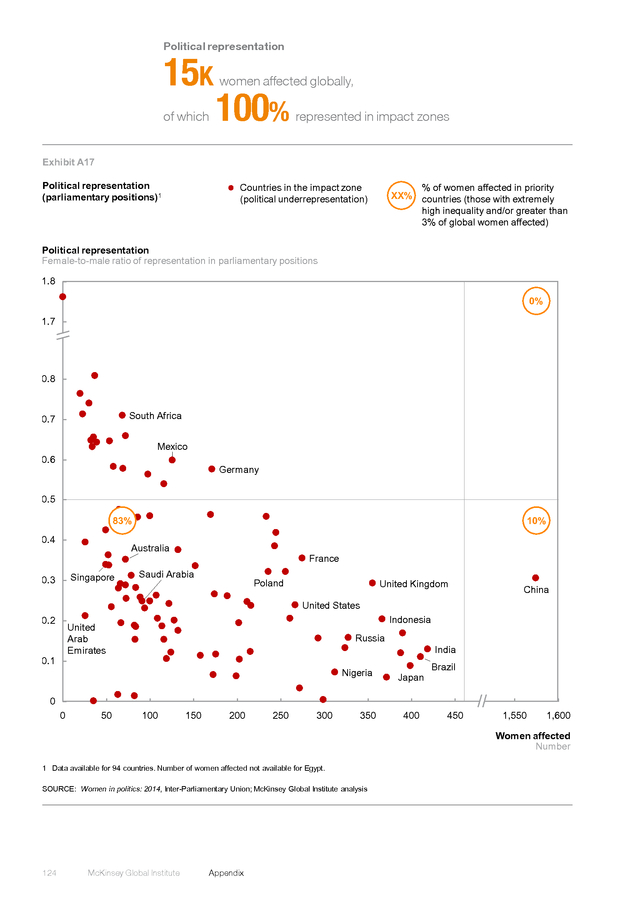

Our analysis finds that 38 out of 91 countries for which we have data have extremely high inequality on this indicator, a blended measure of 11 forms of legal protection for women, spanning laws to protect individuals against violence, ensure parity in inheriting property and accessing institutions, and the right to find work and be fairly compensated. Globally, political participation by women remains very low, with the number of women in ministerial and parliamentary roles only 22 percent that of men. Even in developed economies—and democracies—such as the United Kingdom and the United States, the share of women in such positions is still only 24 percent and 34 percent, respectively.

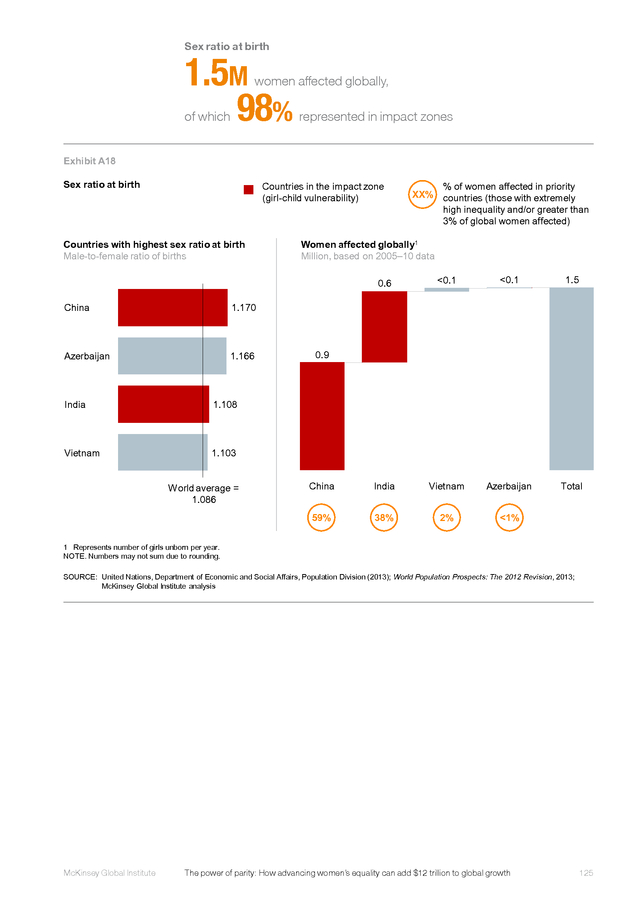

One cross-country study found that greater representation of women in parliaments led to higher expenditure on education as a share of GDP.8 In India, women’s leadership in local politics has been found to reduce corruption.9 ƒƒ Physical security and autonomy. We assess this dimension in terms of three indicators: missing women arising from the preference for a boy child, child marriage, and violence against women. The sex ratio at birth is a source of low inequality globally, but it is a severe issue in a few countries where, by our estimate, about 1.5 million girls are not born each year because of selective abortions that favor male children.10 That number is roughly equal to the number of deaths worldwide due to hypertensive heart disease or diabetes.

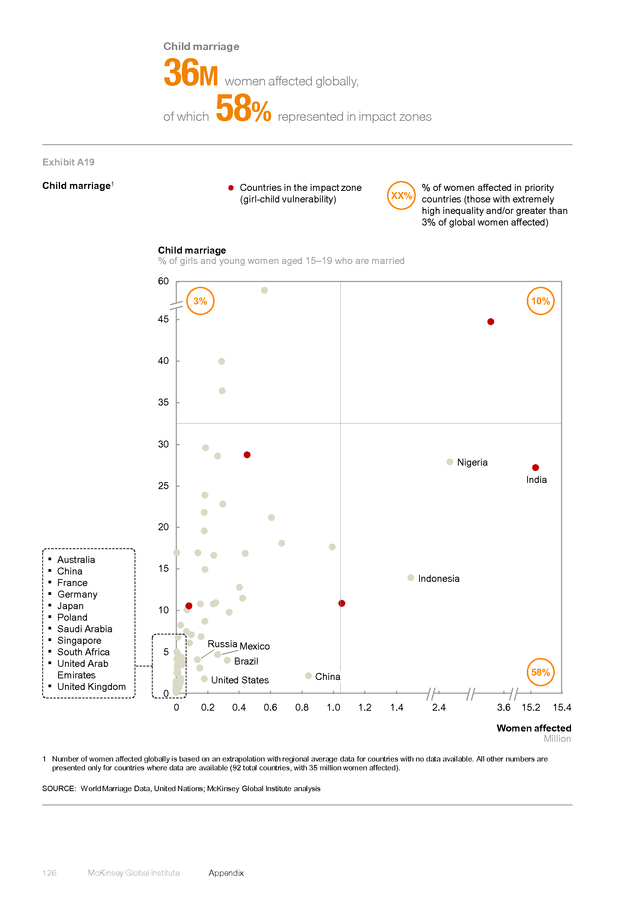

Globally, an estimated 36 million girls marry between the ages of 15 and 19, limiting the degree to which they can receive an education and participate Li-Ju Chen, Female policymakers and educational expenditures: Cross-country evidence, January 2009. Esther Duflo and Petia Topalova, Unappreciated service: Performance, perceptions, and women: Leaders in India, MIT economic faculty paper, October 2004. 10 Based on MGI calculations. Other research from the World Bank has estimated that there are 3.9 million missing women globally each year, of which two-fifths (or 1.56 million) are due to sex-selective abortions. See World development report 2012: Gender equality and development, World Bank, September 2011. 8 9 McKinsey Global Institute The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth 9 .

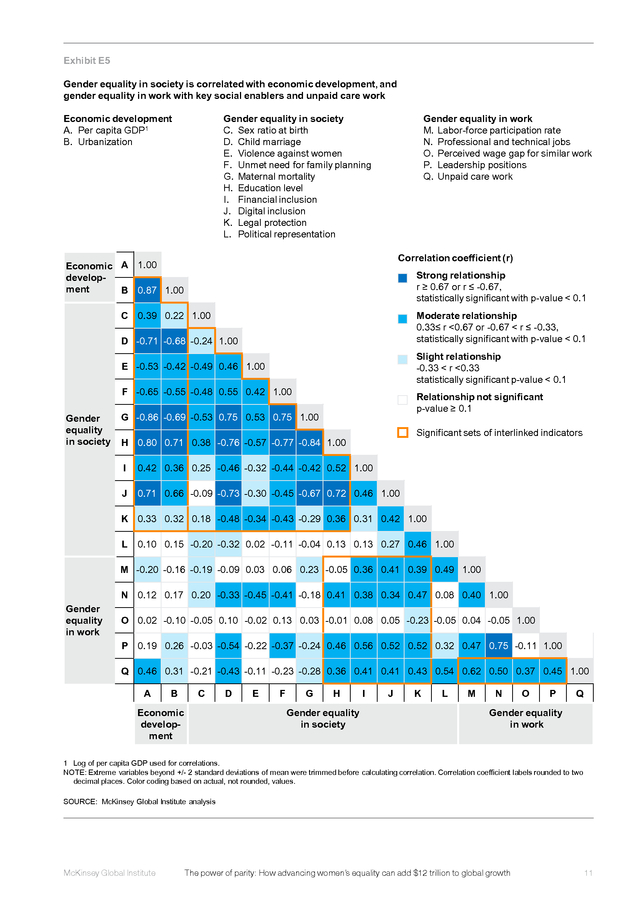

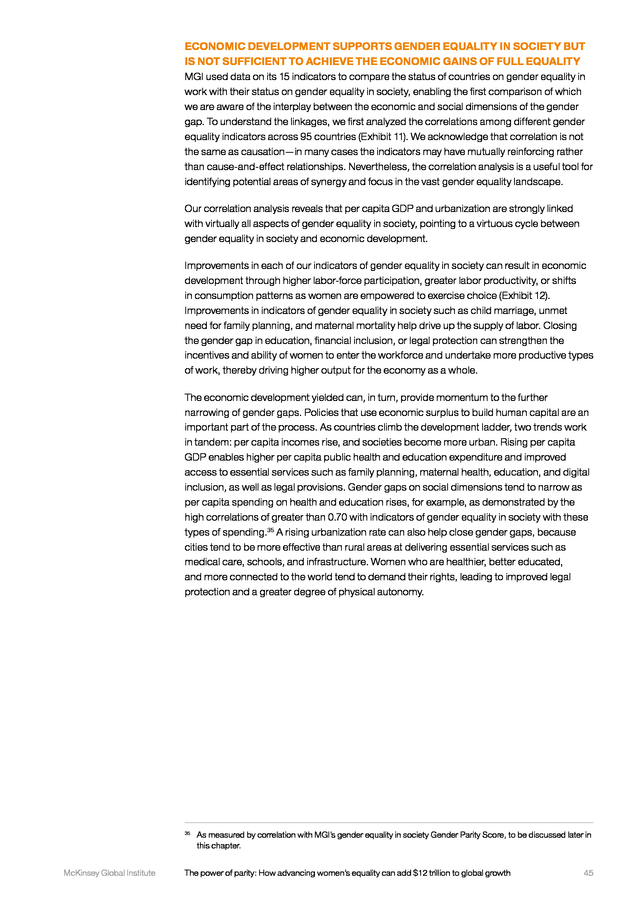

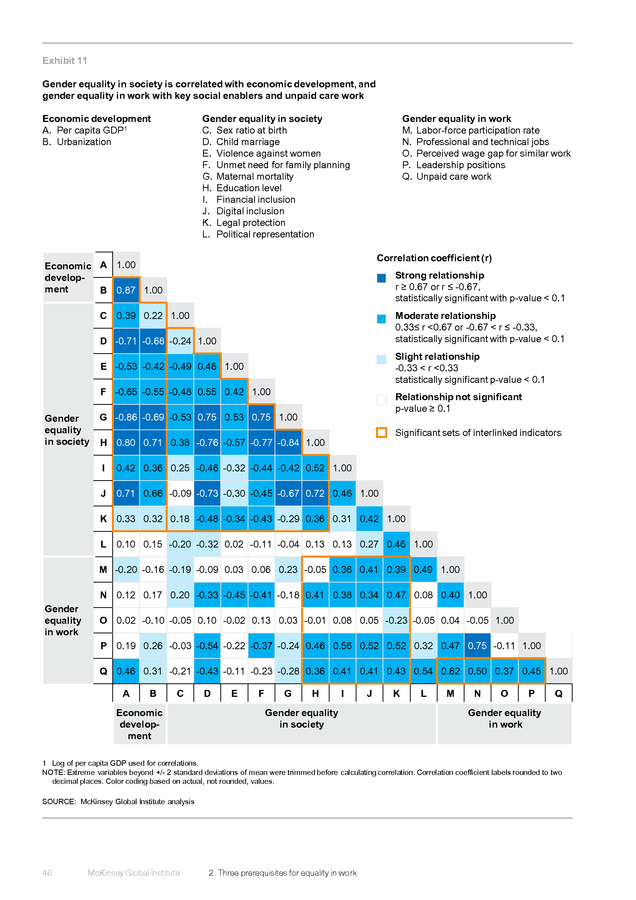

in the workforce.11 Nearly 30 percent of women worldwide, or 723 million women, have been the victims of violence, as measured by MGI’s indicator of violence from an intimate partner. Economic development will help, but specific action in four areas is necessary to achieve gender equality at work more quickly To understand the relationships between gender equality indicators as well as the role of economic development, we analyzed the correlations between different gender equality indicators across 95 countries and with indicators of overall economic development such as per capita GDP and urbanization. We acknowledge that correlation is not the same as causation. In many cases, the indicators may have mutually reinforcing rather than causeand-effect relationships. Nevertheless, the correlation analysis is a useful tool for identifying potential areas of synergy and focus in the vast gender equality landscape. The correlation analysis suggests that per capita GDP and urbanization are linked strongly with virtually all aspects of gender equality in society (Exhibit E5).

Economic development can create momentum toward a further narrowing of gender gaps, provided countries use the dividend of higher GDP growth to boost investment in inclusive social spending and urbanization. Achieving gender equality through economic development is, however, a slow process, and economic development does not have a decisive impact on equality in work and on many broader gender equality indicators. For instance, violence against women does tend to be lower in more developed countries, but prevalence is still high. Similarly, the global average maternal mortality rate decreased from 276 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1995 to 135 in 2013; at this rate of decline, however, the rate will still be as high as 84 deaths in 2025.12 Moreover, economic development has a more nuanced relationship with labor-force participation; female labor-participation rates dip in middle-income countries and rise again in more advanced economies.

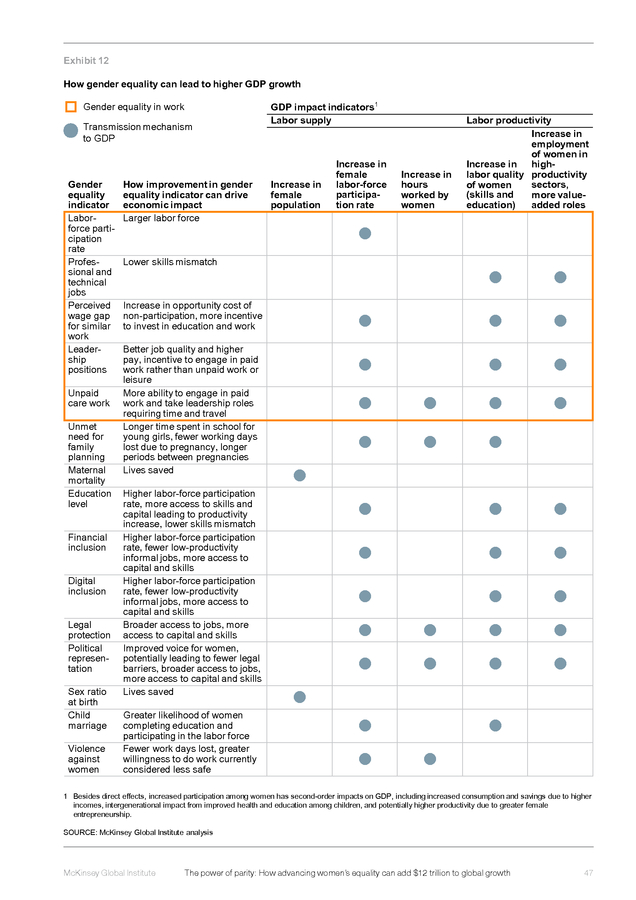

This reflects a combination of cultural barriers and personal preferences as the opportunity cost of women working changes compared with the cost of caring for children and the elderly. The correlation analysis suggests that acting to make improvements on four areas appears to be the most promising route to accelerating gender equality in work: education level, financial and digital inclusion (we consider these together as the delivery models for financing are closely tied with digital channels), legal protection, and unpaid care work. Apart from being closely linked to equality in work, they also lay the groundwork for improvements in access to health care, physical security, and political participation. Putting energy, effort, and resources into these four areas is likely to generate far-reaching impact and social change. 11 12 10 UNFPA, Marrying too young: End child marriage, 2012. Based on a weighted average across a 95-country sample using the female population in 2014. McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary . Exhibit E5 Gender equality in society is correlated with economic development, and gender equality in work with key social enablers and unpaid care work Economic development A. Per capita GDP1 B. Urbanization Gender equality in work M. Labor-force participation rate N.

Professional and technical jobs O. Perceived wage gap for similar work P. Leadership positions Q.

Unpaid care work Gender equality in society C. Sex ratio at birth D. Child marriage E.

Violence against women F. Unmet need for family planning G. Maternal mortality H.

Education level I. Financial inclusion J. Digital inclusion K.

Legal protection L. Political representation Correlation coefficient (r) Economic A 1.00 development B 0.87 1.00 Strong relationship r ≥ 0.67 or r ≤ -0.67, statistically significant with p-value < 0.1 Moderate relationship 0.33≤ r <0.67 or -0.67 < r ≤ -0.33, statistically significant with p-value < 0.1 C 0.39 0.22 1.00 D -0.71 -0.68 -0.24 1.00 Slight relationship -0.33 < r <0.33 statistically significant p-value < 0.1 E -0.53 -0.42 -0.49 0.46 1.00 F -0.65 -0.55 -0.48 0.55 0.42 1.00 Gender equality in society Relationship not significant p-value ≥ 0.1 G -0.86 -0.69 -0.53 0.75 0.53 0.75 1.00 Significant sets of interlinked indicators H 0.80 0.71 0.38 -0.76 -0.57 -0.77 -0.84 1.00 I 0.42 0.36 0.25 -0.46 -0.32 -0.44 -0.42 0.52 1.00 J 0.71 0.66 -0.09 -0.73 -0.30 -0.45 -0.67 0.72 0.46 1.00 K 0.33 0.32 0.18 -0.48 -0.34 -0.43 -0.29 0.36 0.31 0.42 1.00 L 0.10 0.15 -0.20 -0.32 0.02 -0.11 -0.04 0.13 0.13 0.27 0.46 1.00 M -0.20 -0.16 -0.19 -0.09 0.03 0.06 0.23 -0.05 0.36 0.41 0.39 0.49 1.00 Gender equality in work N 0.12 0.17 0.20 -0.33 -0.45 -0.41 -0.18 0.41 0.38 0.34 0.47 0.08 0.40 1.00 O 0.02 -0.10 -0.05 0.10 -0.02 0.13 0.03 -0.01 0.08 0.05 -0.23 -0.05 0.04 -0.05 1.00 P 0.19 0.26 -0.03 -0.54 -0.22 -0.37 -0.24 0.46 0.56 0.52 0.52 0.32 0.47 0.75 -0.11 1.00 Q 0.46 0.31 -0.21 -0.43 -0.11 -0.23 -0.28 0.36 0.41 0.41 0.43 0.54 0.62 0.50 0.37 0.45 1.00 A B C D E F G H Gender equality in society Economic development I J K L M N O P Q Gender equality in work 1 Log of per capita GDP used for correlations. NOTE: Extreme variables beyond +/- 2 standard deviations of mean were trimmed before calculating correlation. Correlation coefficient labels rounded to two decimal places.

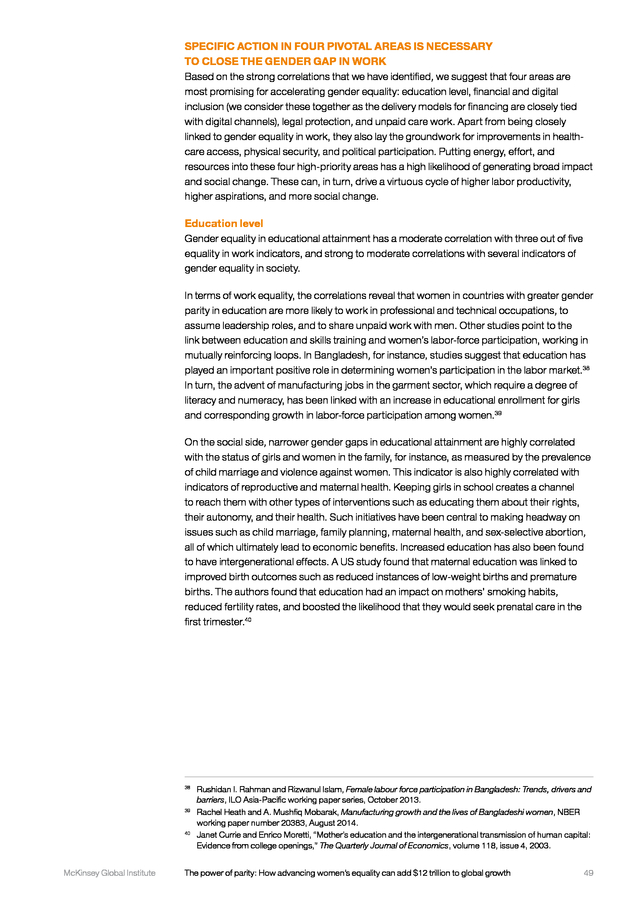

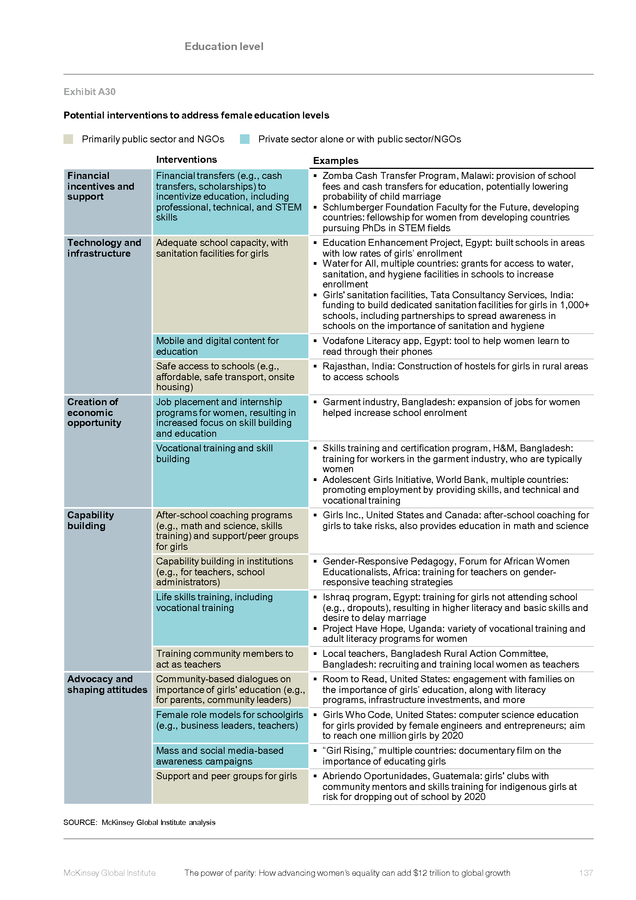

Color coding based on actual, not rounded, values. SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis McKinsey Global Institute The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth 11 . ƒƒ Education level. Gender equality in educational attainment has a moderate or strong correlation with three out of five work equality indicators and several indicators of gender equality in society. Women who enjoy parity in education are more likely to share unpaid work with men more equitably, to work in professional and technical occupations, and to assume leadership roles. Narrower gender gaps in educational attainment are strongly correlated with the status of girls and women in the family, measured by the prevalence of child marriage and violence against women.

Higher education and skills training raise women’s labor participation. Keeping girls in school for longer provides a space to help educate them about their rights and their health, and helps to make headway on child marriage, family planning, maternal health, and sex-selective abortion. ~50% OF 4.4B people offline are women ƒƒ Financial and digital inclusion. Gender parity in access to the Internet and mobile phones, and parity in access to financial services each show moderate correlations with multiple indicators of work equality.

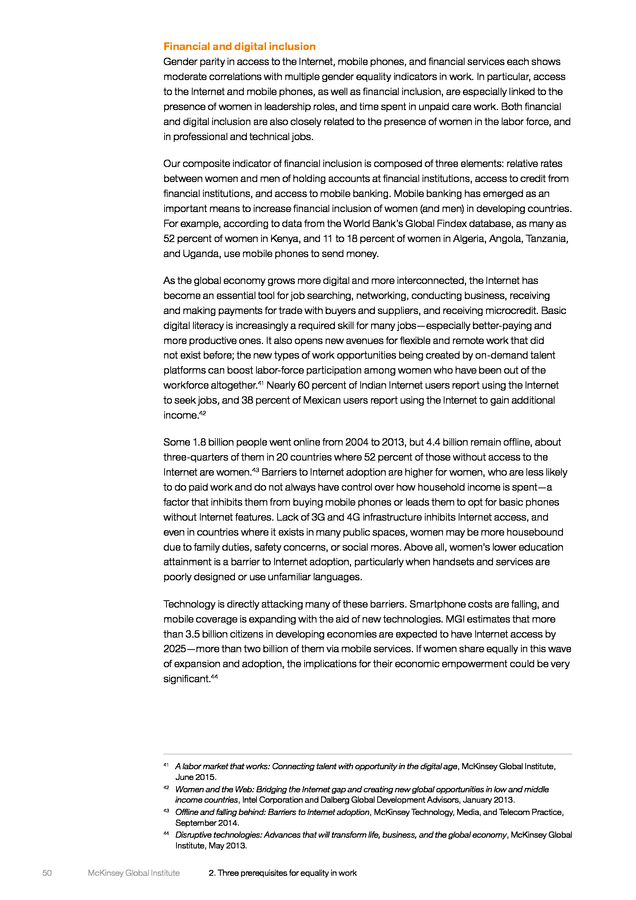

In particular, access to the Internet and mobile phones and financial inclusion are especially linked to the presence of women in leadership roles and time spent in unpaid care work. As the global economy becomes more digital and more interconnected, the Internet has evolved into an essential tool for job searching, networking, conducting business, receiving and making payments for trade with buyers and suppliers, and receiving microcredit. Yet, based on an MGI study, some 4.4 billion people, 52 percent of them women, are offline.

MGI estimates that more than 3.5 billion citizens in developing economies are expected to have Internet access by 2025, more than two billion of them via mobile services. If women were to share equally in this wave of expansion and adoption, the implications for their work equality could be very significant.13 ƒƒ Legal protection. Legal provisions outlining and guaranteeing the rights of women as full members of society show a moderate correlation with four out of five work equality indicators and several indicators of gender equality in society, including violence against women, child marriage, unmet need for family planning, and education.

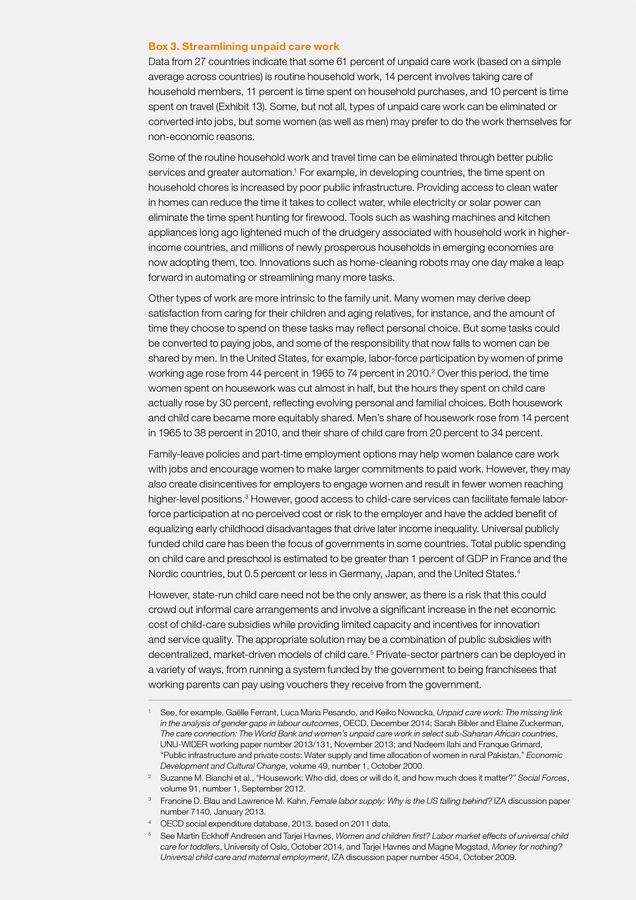

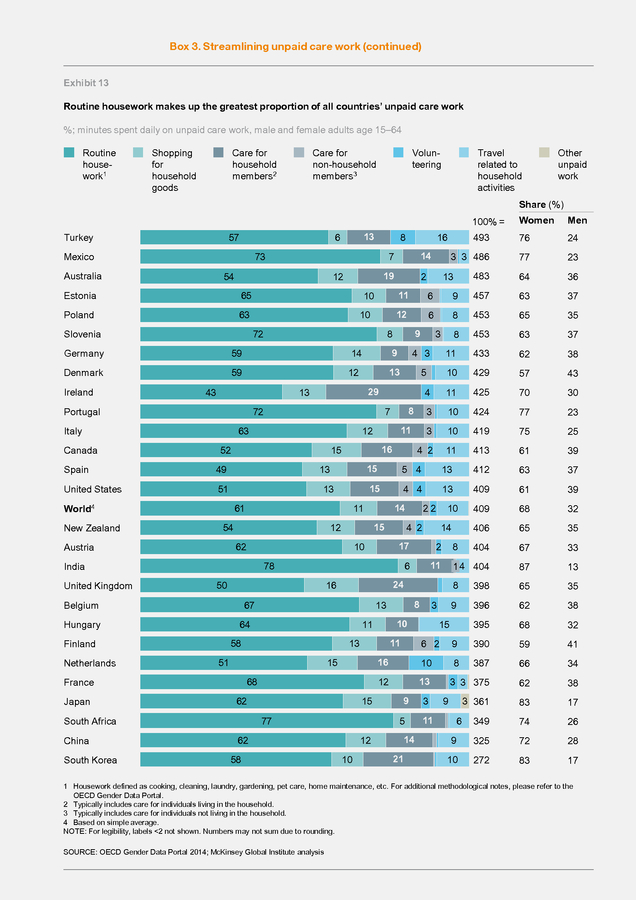

Other researchers have also highlighted the link between equality in legal provisions and the increased labor-force participation rate of women.14 ~61% of unpaid care work is routine household chores ƒƒ Unpaid care work. The share of women engaged in unpaid work relative to men has a high correlation with female labor-force participation rates and a moderate correlation with their chances of assuming leadership positions and participating in professional and technical jobs. Unpaid work by women also shows strong to moderate correlation with education levels, financial and digital inclusion, and legal protection.

Based on analysis of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data, some 61 percent of unpaid care work is routine household work such as cooking, cleaning, collecting water and firewood, home maintenance, and gardening. Other types of work intrinsic to the family unit are caring for children and aging relatives. Such work may be done willingly and contribute to personal and family well-being.

However, some of it could be reduced or eliminated through improved infrastructure and automation, shared more equitably by male and female members of the household, or converted into paid jobs, including through state-funded or market-driven care services. It should be noted that some of these interventions would result in higher GDP to the extent that time saved by women is used for paid work. Beyond GDP, there could be other positive effects.

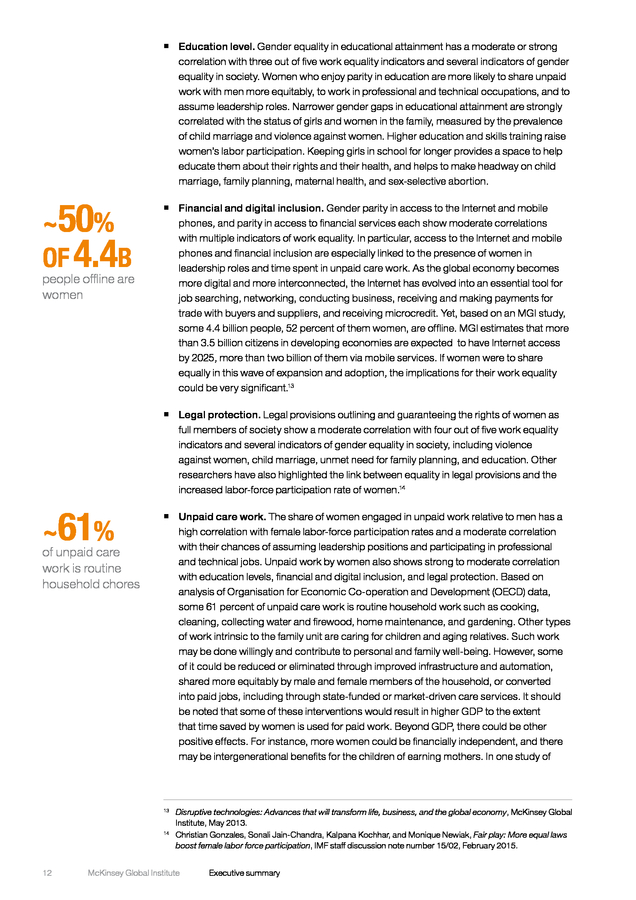

For instance, more women could be financially independent, and there may be intergenerational benefits for the children of earning mothers. In one study of Disruptive technologies: Advances that will transform life, business, and the global economy, McKinsey Global Institute, May 2013. 14 Christian Gonzales, Sonali Jain-Chandra, Kalpana Kochhar, and Monique Newiak, Fair play: More equal laws boost female labor force participation, IMF staff discussion note number 15/02, February 2015. 13 12 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary . 24 countries, daughters of working mothers were more likely to be employed, have higher earnings, and hold supervisory roles.15 To supplement the correlation analysis, MGI calculated a Gender Parity Score using the 15 indicators to measure how far each country is from full gender parity. The GPS weights each indicator equally and calculates an aggregate measure at the country level of how close women are to gender parity in each of the 95 countries, where a GPS of 1.00 indicates parity. We also calculate GPS for subgroups of indicators, specifically comparing GPS on work equality indicators with the GPS on indicators relating to equality in society. This enables what, to our knowledge, is the first comparison of the interplay between the economic and social dimensions of the gender gap. Broadly speaking, an increase in gender equality in society is linked with an increase in gender equality in work. While absolute scores on gender equality in society tend to be higher than those of gender equality in work for most countries, virtually no country has high gender equality in society and low equality in work (Exhibit E6). Exhibit E6 Gender equality in society is linked with gender equality in work Per capita GDP levels, 2014 purchasing-power-parity international dollar <5,000 5,000–10,000 10,000–15,000 15,000–25,000 25,000–50,000 >50,000 Gender Parity Score: Gender equality in work (parity = 1.00)1 0.8 0.7 Correlation coefficient (r) = 0.51 Group 2 Relatively high equality in work Example countries: Ethiopia, Nigeria, Thailand 0.6 0.5 Group 1 Relatively gender-equal on both dimensions Example countries: France, Germany, Norway 0.4 Group 3 Relatively low gender equality on both dimensions Example countries: Egypt, India, United Arab Emirates 0.3 0.2 0.40 0.45 0.50 0.55 0.60 0.65 0.70 0.75 0.80 0.85 0.90 Gender Parity Score: Gender equality in society (parity = 1.00)2 1 Labor-force participation rate, professional and technical jobs, perceived wage gap for similar work, leadership positions, unpaid care work. 2 Essential services and enablers of economic opportunity, legal protection and political voice, physical security and autonomy. SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis REPEATS as x14 Kathleen L.

McGinn, Mayra Ruiz Castro, and Elizabeth Long Lingo, Mums the word! Cross-national effects of maternal employment on gender inequalities at work and at home, Harvard Business School working paper 15-094, June 2015. 15 McKinsey Global Institute The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth 13 . Countries in Group 1 are relatively gender-equal on both dimensions, although even they have scope to improve their GPS on gender equality in society and in work. Countries in Group 2 have achieved relatively high gender equality in work, as women’s participation in the labor force is high. But many women in these economies are engaged in nearsubsistence agriculture or low-value-adding jobs, and may lack the wherewithal to rise beyond the initial rungs of the work ladder. Countries in Group 3 are characterized by low gender equality in both work and society.

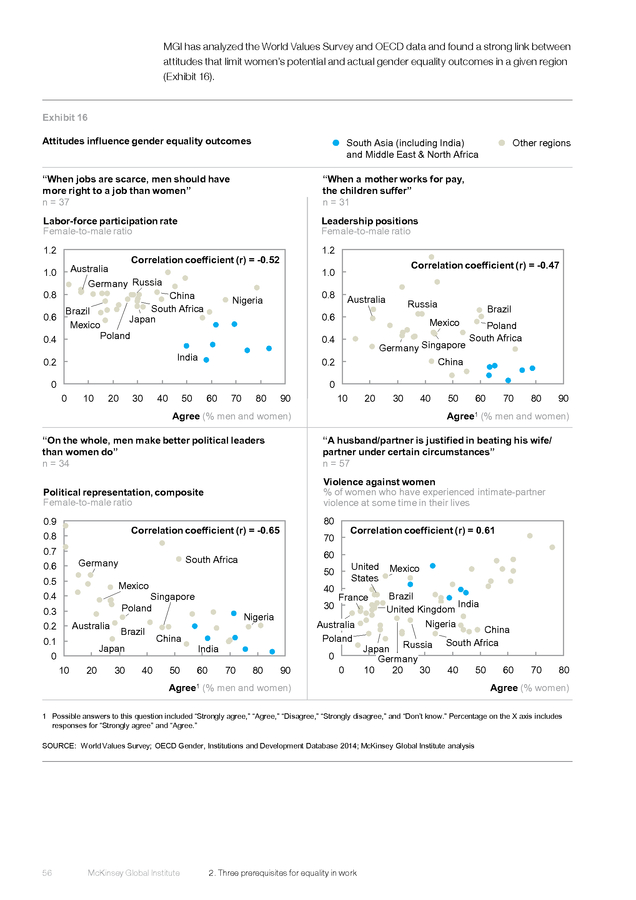

In many countries across these groups, a lack of skills and cultural norms could constrain the roles available to women. Shifts in deep-seated attitudes and beliefs would be necessary to address gender inequality at work Even relatively equal societies still have significant gender gaps. This reflects the fact that cultural attitudes play a strong role in influencing the status of women in society and in work. Attitudes among both men and women shape the level of gender parity considered appropriate or desirable within each society.

For example, demographic and health surveys find that women believe that arguing with their husbands, refusing to have sex, burning food, or going out without telling the husband are all justifiable reasons for domestic violence.16 MGI has analyzed the World Values Survey and data from the OECD and found a strong link between attitudes that limit women’s potential and the actual gender equality outcomes in a given region. For instance, the survey asked respondents, both men and women, whether they agreed with the following statements: “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women” and “When a mother works for pay, the children suffer.” We examined the responses against outcomes relating to equality in work and found strong correlations with both. More than half of the respondents in South Asia and MENA agreed with both statements—and these regions have some of the world’s lowest rates of women’s labor-force participation.

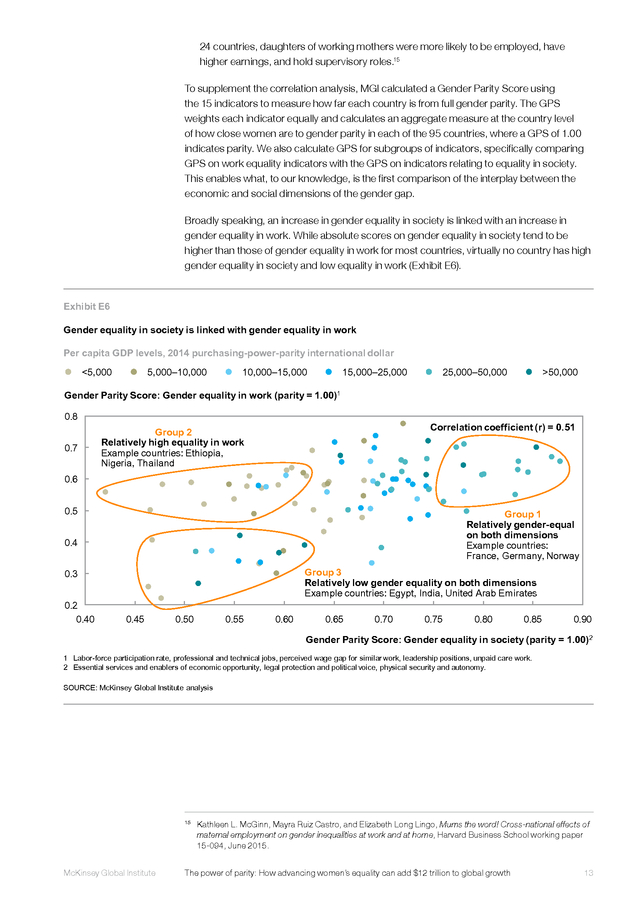

These beliefs persist even in a sizable proportion of respondents in developed countries. GPS lowest in South Asia (excluding India) at 0.44 and highest in North America and Oceania at 0.74 THE DISTANCE FROM GENDER PARITY VARIES FOR DIFFERENT COUNTRIES MGI’s GPS scoring system enables us to gauge the distance countries have traveled toward gender parity and therefore the size of the gap that individual countries would need to bridge to achieve parity. MGI calculated a GPS for each country and for each region, weighting country scores on the size of the female population in each country in a particular region, where a GPS of 1.00 indicates full parity. We also calculated GPS for individual dimensions of gender equality such as essential services and enablers of economic opportunity, and physical security and autonomy, as well as for groups of indicators in the categories of equality in work and equality in society. The world’s performance on closing the gender gap appears poor when MGI’s comprehensive lens of 15 indicators is used.

By MGI’s Gender Parity Score based on 15 indicators, 12 countries (Bangladesh, Chad, Egypt, India, Iran, Mali, Niger, Oman, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Yemen) have closed less than 50 percent of the gender gap. The regional GPS is lowest—meaning that this region has the furthest to travel to achieve gender parity—in South Asia (excluding India) at 0.44, and highest in North America and Oceania at 0.74 (Exhibit E7). Sunita Kishor and Kiersten Johnson, Profiling domestic violence: A multi-country study, Measure DHS+, June 2004. 16 14 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary . Exhibit E7 Regions have distinct levels and patterns of gender equality Level of gender inequality Region Extremely high North America and Western Oceania Europe 0.74 0.71 High Eastern Europe and Central Asia 0.67 Aggregate GPS1 Gender equality in work Labor-force participation rate Essential services and enablers of economic opportunity Health-care2 and education level Legal protection and political voice Political representation Physical security and autonomy Violence against women 0.72 0.60 0.67 Medium East and Southeast Asia Latin (excluding America China) 0.64 0.62 0.54 0.58 Low China 0.50 0.84 0.67 0.71 0.82 0.93 0.91 0.91 0.89 0.87 0.93 0.65 0.50 0.59 0.32 0.35 0.49 0.17 0.81 0.87 0.90 0.67 0.78 0.81 0.93 0.45 0.89 0.28 0.48 0.44 0.30 0.30 0.32 0.34 0.51 0.78 0.75 0.69 0.89 0.81 0.81 0.24 0.20 0.11 0.15 0.73 0.70 0.63 0.56 0.56 0.78 0.93 0.48 0.34 0.57 0.79 0.95 India South Asia (excluding India) Middle East and SubSaharan North Africa Africa 0.61 0.82 0.96 GPS for indicator or set of indicators GPS 0.97 0.63 0.36 0.35 0.31 0.30 0.16 0.19 0.81 0.87 0.89 0.63 0.75 0.85 0.74 0.60 0.16 0.12 0.83 0.63 1 All GPS calculations are conducted using a sum of squares method with equal weighting across indicators. For all categories, color coding is in line with impact zones. Color coding for aggregate GPS is based on thresholds for majority of indicators. 2 Comprising unmet need for family planning and maternal mortality. NOTE: Numbers are rounded to two decimal places. Color coding is based on actual, not rounded, values. SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis McKinsey Global Institute The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth 15 .

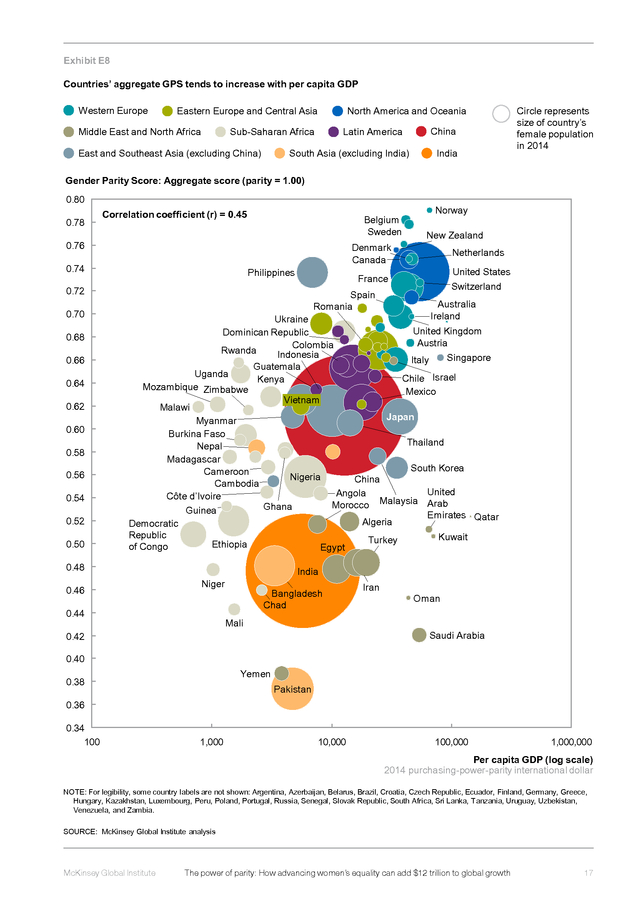

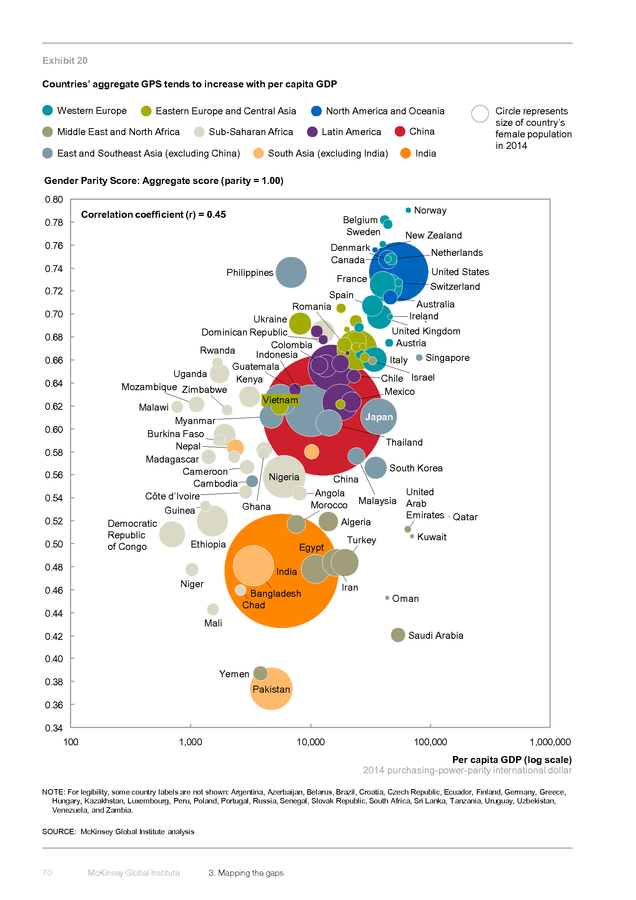

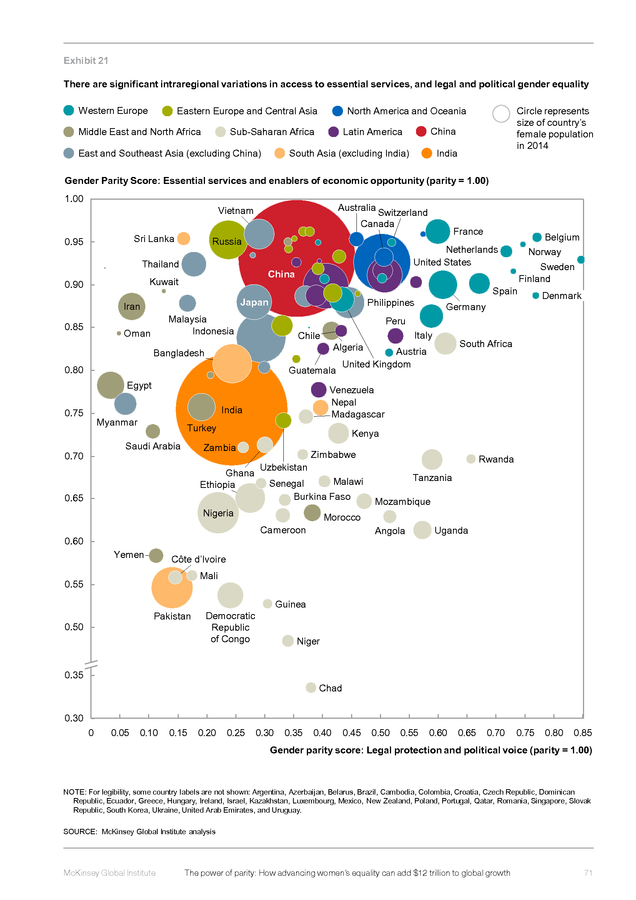

Some of the findings of the GPS analysis may be surprising. Women in South Asia (excluding India) have a higher per capita GDP of about $4,340 on a 2014 purchasing power parity basis than those in sub-Saharan Africa, whose average per capita GDP is $3,680, but they face higher gender inequality than women in sub-Saharan Africa. Chinese women have about the same access to essential services as women in developed economies, but have higher gender gaps in aspects of equality in work. Women in Western Europe and the North America and Oceania region are the closest to gender parity in all ten regions.

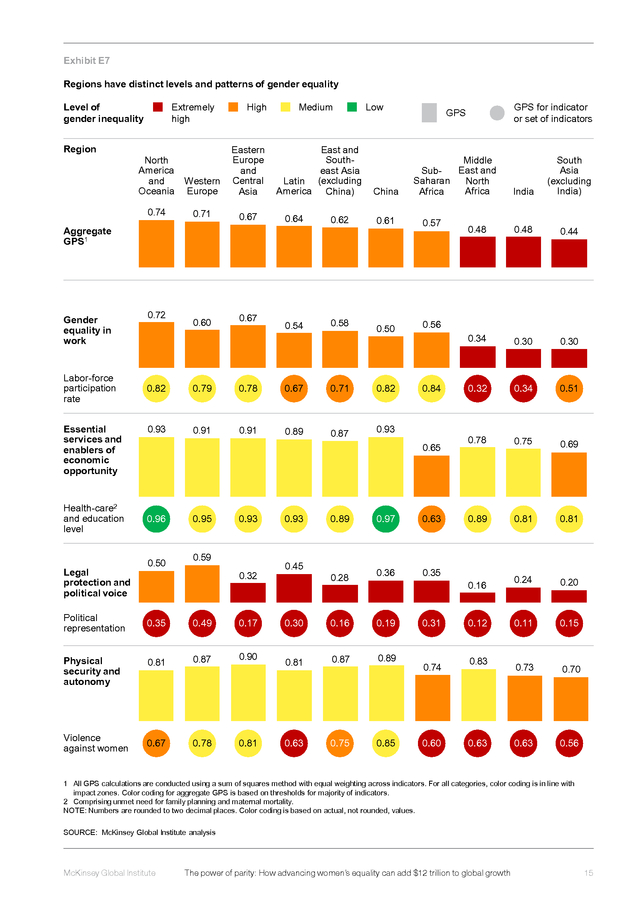

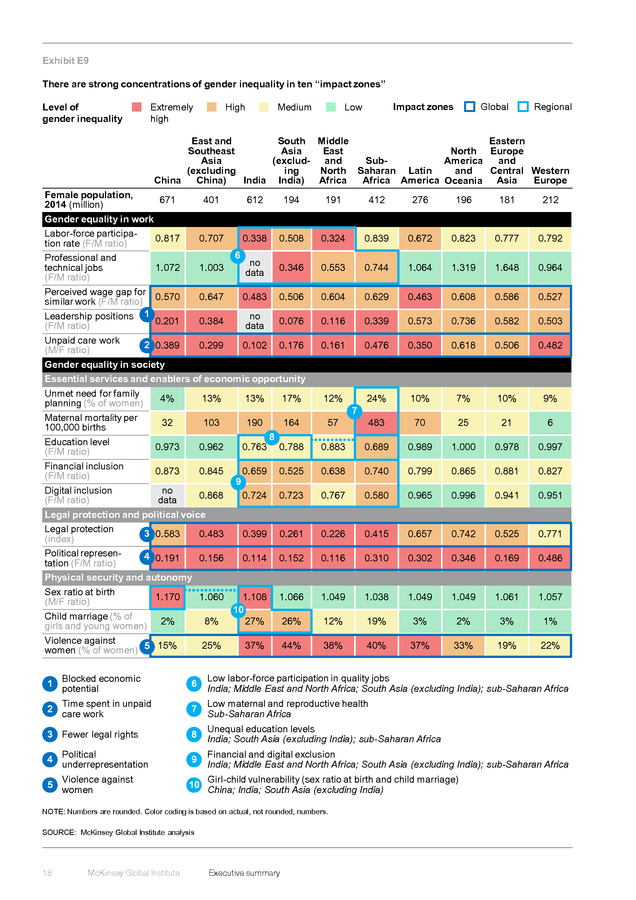

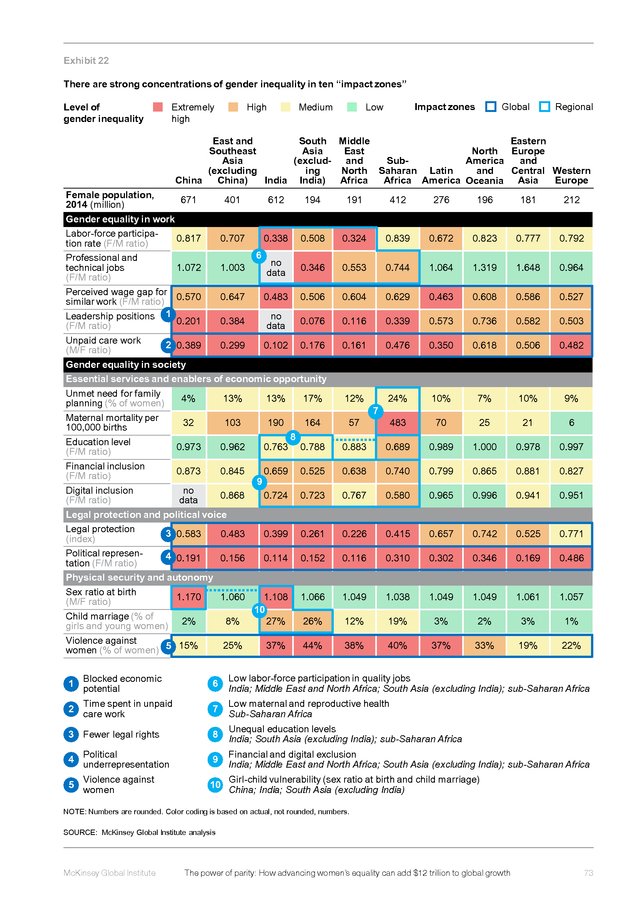

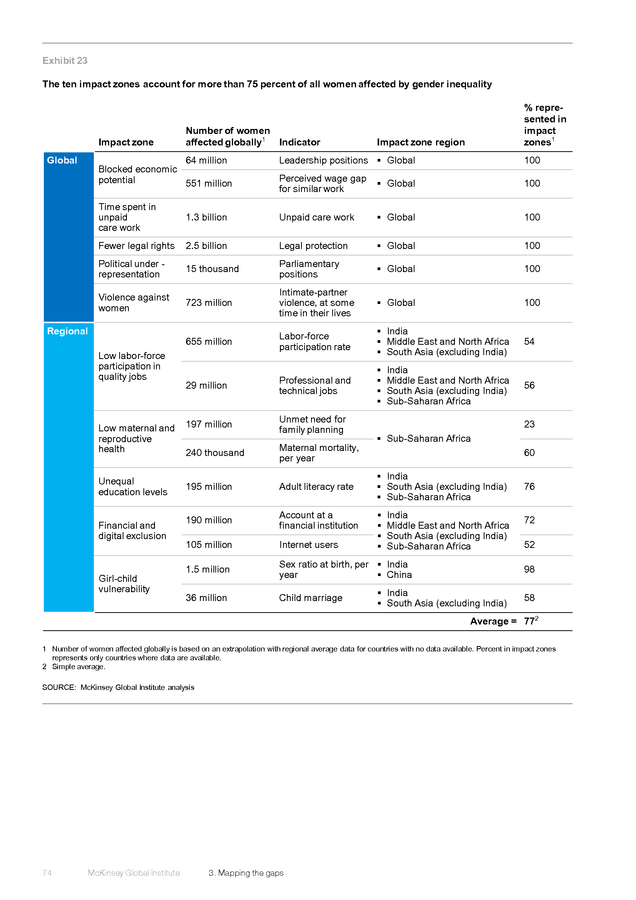

But women in Western Europe tend to have higher political participation and somewhat higher physical security, while women in North America tend to be more empowered on virtually all dimensions of work equality. While countries’ GPS tends to be largely in line with that of their region, economic, cultural, and political factors drive significant differences within regions (Exhibit E8). For instance, some countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Mali, and Niger) have significantly higher gaps on essential services and enablers of economic opportunity relative to other sub-Saharan African countries, including Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Rwanda, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Women in Austria, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, and the United Kingdom have lower political participation than those in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. TO HELP PRIORITIZE POTENTIAL ACTION, MGI HAS IDENTIFIED TEN “IMPACT ZONES” THAT ACCOUNT FOR MORE THAN 75 PERCENT OF THE GLOBAL GENDER GAP All forms of gender inequality need to be tackled, but, given the magnitude of the gap and limitations on resources, it is important for governments, foundations, and private-sector organizations to focus their efforts.

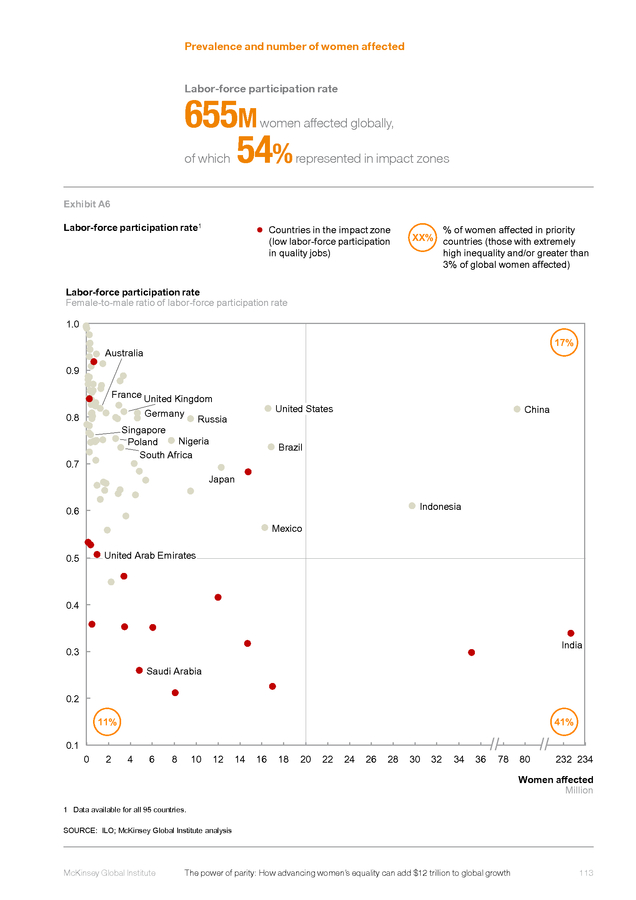

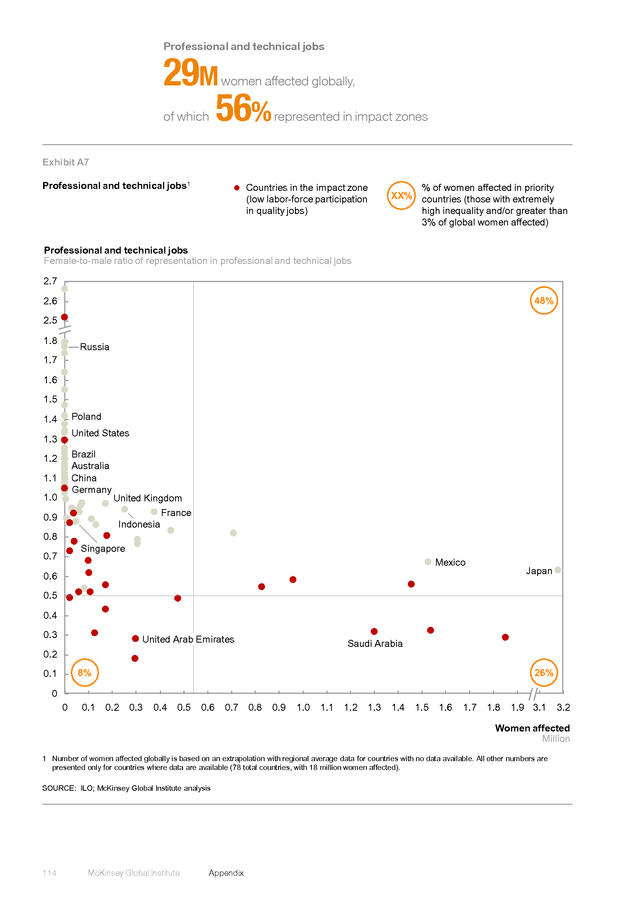

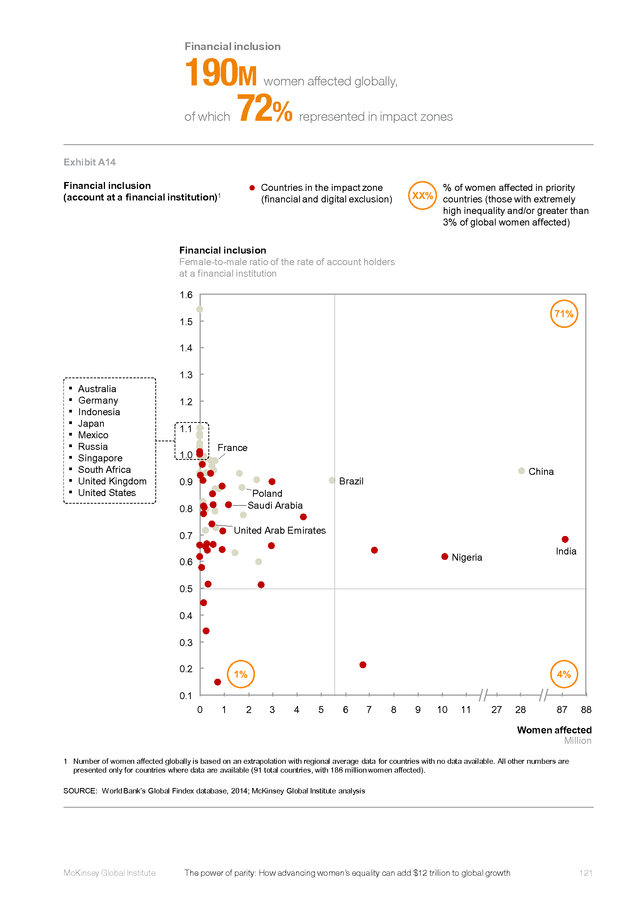

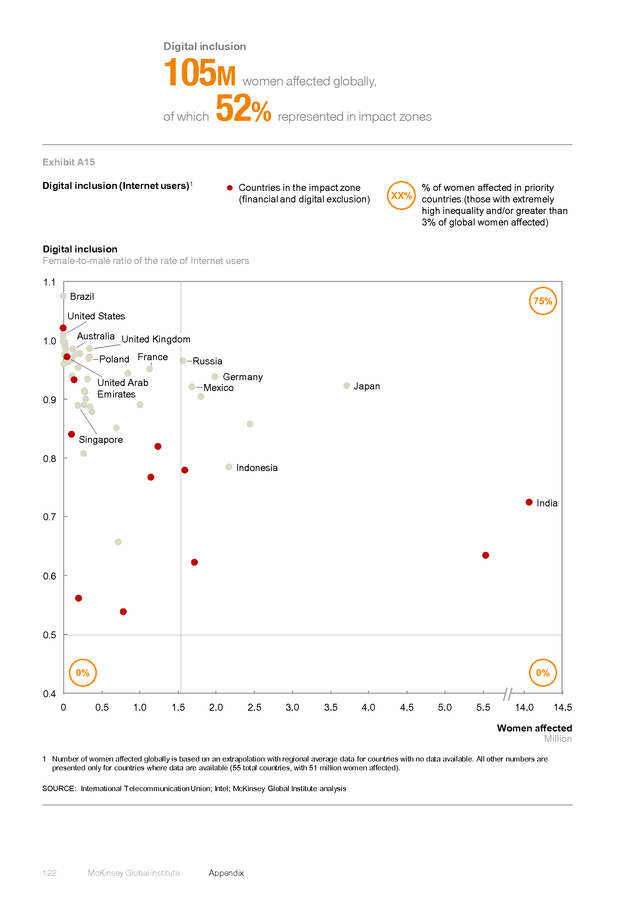

In order to help them do so, MGI has identified ten “impact zones,” which reflect both the seriousness of a type of gender inequality and its geographic concentration (Exhibit E9).17 The global impact zones are blocked economic potential; time spent in unpaid care work; fewer legal rights; political underrepresentation; and violence against women. The regional impact zones are low labor-force participation in quality jobs; low maternal and reproductive health; unequal education levels; financial and digital exclusion; and girl-child vulnerability. Effective action in these zones alone would move more than 75 percent of women affected by gender inequality globally closer to parity. It could help as many as 76 percent of women affected by adult literacy gaps, 72 percent of those with unequal access to financial inclusion, 60 percent of those affected by maternal mortality issues, 58 percent of those affected by child marriage, and 54 percent of women disadvantaged by unequal labor-force participation rates. Regional numbers for gender equality indicators typically represent weighted averages based on 2014 female population data available from the UN.

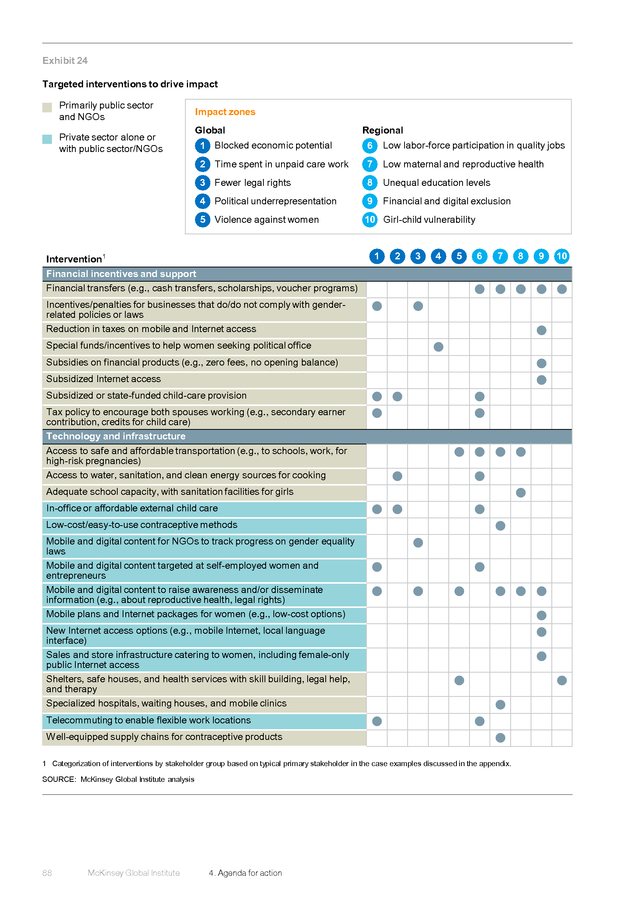

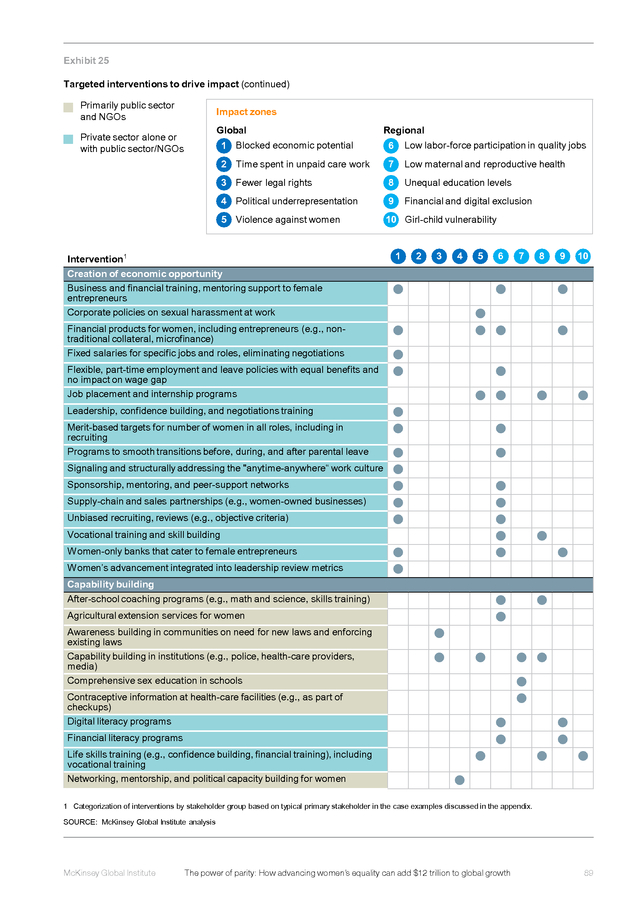

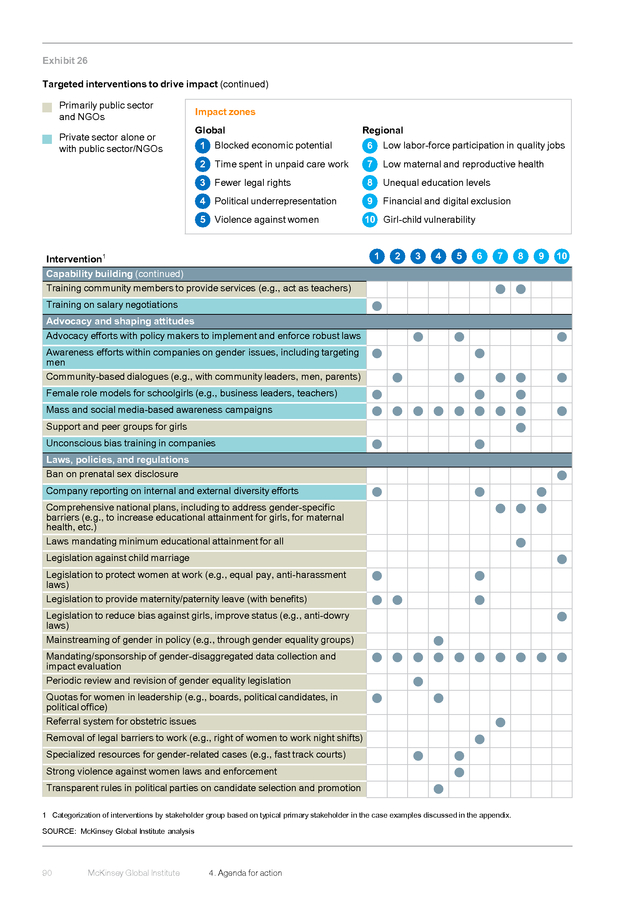

Per capita GDP is based on data from the IMF and represents values in 2014 international dollars adjusted for purchasing power parity. 17 16 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary . Exhibit E8 Countries’ aggregate GPS tends to increase with per capita GDP Western Europe Eastern Europe and Central Asia Middle East and North Africa North America and Oceania Sub-Saharan Africa East and Southeast Asia (excluding China) Latin America South Asia (excluding India) China India Circle represents size of country’s female population in 2014 Gender Parity Score: Aggregate score (parity = 1.00) 0.80 0.78 Correlation coefficient (r) = 0.45 Belgium Sweden 0.76 0.74 Denmark Canada Philippines 0.68 0.66 0.64 0.62 0.60 0.58 0.56 0.54 0.52 0.50 New Zealand Netherlands United States Switzerland France 0.72 0.70 Norway Spain Romania Australia Ireland Ukraine United Kingdom Dominican Republic Austria Colombia Rwanda Indonesia Singapore Italy Guatemala Uganda Chile Israel Kenya Mozambique Zimbabwe Mexico Vietnam Malawi Japan Myanmar Burkina Faso Thailand Nepal Madagascar South Korea Cameroon Nigeria China Cambodia United Angola Côte d’Ivoire Morocco Malaysia Arab Ghana Guinea Emirates Qatar Algeria Democratic Republic Kuwait Turkey Ethiopia of Congo Egypt 0.48 0.46 India Niger 0.44 Bangladesh Chad Mali Iran Oman Saudi Arabia 0.42 0.40 Yemen 0.38 Pakistan 0.36 0.34 100 1,000 10,000 100,000 1,000,000 Per capita GDP (log scale) 2014 purchasing-power-parity international dollar NOTE: For legibility, some country labels are not shown: Argentina, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Brazil, Croatia, Czech Republic, Ecuador, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Luxembourg, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Senegal, Slovak Republic, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, and Zambia. SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis McKinsey Global Institute The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth 17 . Exhibit E9 There are strong concentrations of gender inequality in ten “impact zones” Level of gender inequality Extremely high High Medium Impact zones Low Global Regional Eastern East and South Middle Southeast Asia East North Europe and Asia (exclud- and America Suband Central Western (excluding ing North Saharan Latin Africa America Oceania Asia Europe China China) India India) Africa Female population, 671 401 612 194 2014 (million) Gender equality in work Labor-force participa0.817 0.707 0.338 0.508 tion rate (F/M ratio) 6 Professional and no technical jobs 1.072 1.003 0.346 data (F/M ratio) Perceived wage gap for 0.647 0.483 0.506 similar work (F/M ratio) 0.570 Leadership positions 1 no 0.201 0.384 0.076 (F/M ratio) data Unpaid care work 2 0.389 0.299 0.102 0.176 (M/F ratio) Gender equality in society Essential services and enablers of economic opportunity Unmet need for family 4% 13% 13% 17% planning (% of women) Maternal mortality per 32 103 190 164 100,000 births 8 Education level 0.973 0.962 0.763 0.788 (F/M ratio) Financial inclusion 0.873 0.845 0.659 0.525 (F/M ratio) 9 Digital inclusion no 0.868 0.724 0.723 (F/M ratio) data Legal protection and political voice Legal protection 3 0.583 0.483 0.399 0.261 (index) Political represen4 0.191 0.156 0.114 0.152 tation (F/M ratio) Physical security and autonomy Sex ratio at birth 1.170 1.060 1.108 1.066 (M/F ratio) 10 Child marriage (% of 8% 27% 26% girls and young women) 2% Violence against 25% 37% 44% women (% of women) 5 15% 191 412 276 196 181 212 0.324 0.839 0.672 0.823 0.777 0.792 0.553 0.744 1.064 1.319 1.648 0.964 0.604 0.629 0.463 0.608 0.586 0.527 0.116 0.339 0.573 0.736 0.582 0.503 0.161 0.476 0.350 0.618 0.506 0.482 24% 10% 7% 10% 9% 483 70 25 21 6 0.883 0.689 0.989 1.000 0.978 0.997 0.638 0.740 0.799 0.865 0.881 0.827 0.767 0.580 0.965 0.996 0.941 0.951 0.226 0.415 0.657 0.742 0.525 0.771 0.116 0.310 0.302 0.346 0.169 0.486 1.049 1.038 1.049 1.049 1.061 1.057 12% 19% 3% 2% 3% 1% 38% 40% 37% 33% 19% 22% 12% 57 7 1 Blocked economic potential 6 Low labor-force participation in quality jobs India; Middle East and North Africa; South Asia (excluding India); sub-Saharan Africa 2 Time spent in unpaid care work 7 Low maternal and reproductive health Sub-Saharan Africa 8 Unequal education levels India; South Asia (excluding India); sub-Saharan Africa 3 Fewer legal rights 4 Political underrepresentation 9 Financial and digital exclusion India; Middle East and North Africa; South Asia (excluding India); sub-Saharan Africa 5 Violence against women 10 Girl-child vulnerability (sex ratio at birth and child marriage) China; India; South Asia (excluding India) NOTE: Numbers are rounded. Color coding is based on actual, not rounded, numbers. SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis 18 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary . SIX TYPES OF INTERVENTION—WITH THE PRIVATE SECTOR PLAYING AN ACTIVE ROLE—ARE NECESSARY TO BRIDGE THE GENDER GAP Across the ten impact zones, MGI identified 75 interventions and more than 150 case examples around the world that have been used to narrow gender gaps, and conducted a meta-analysis of research available. We conclude that these interventions offer promising avenues to explore. It is not possible to assess the impact of all individual interventions for many reasons. Rigorous gender-disaggregated data and impact evaluations are not available for many initiatives.

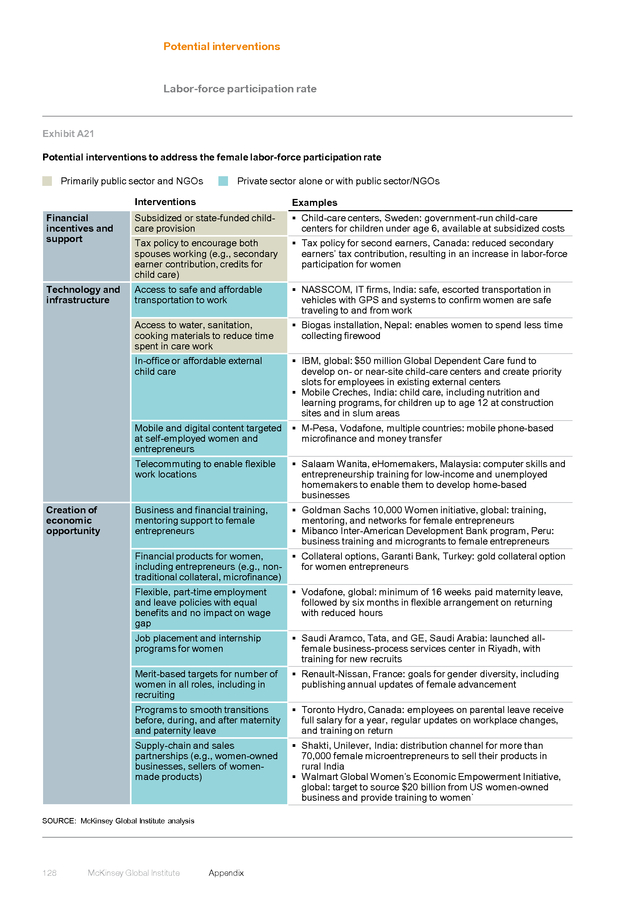

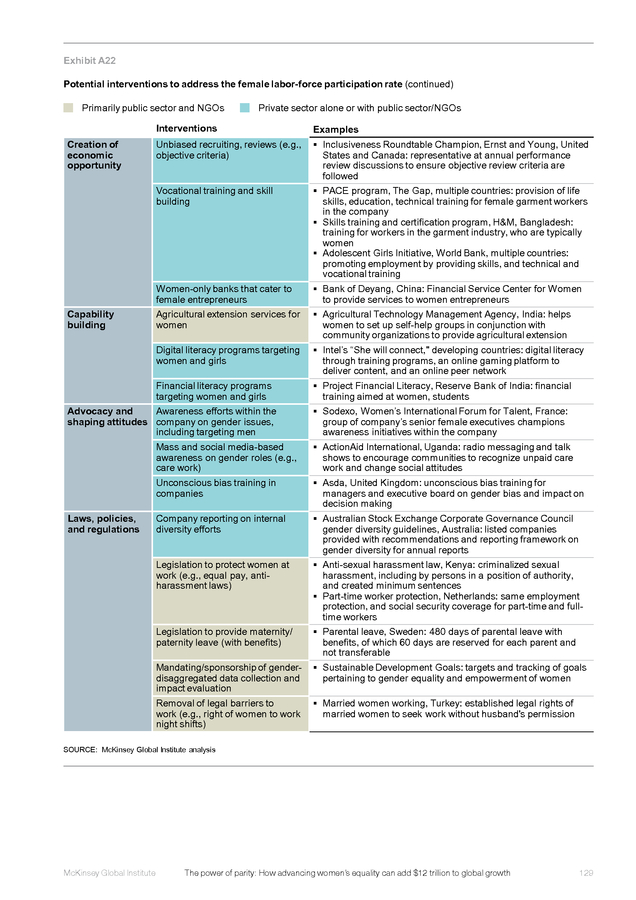

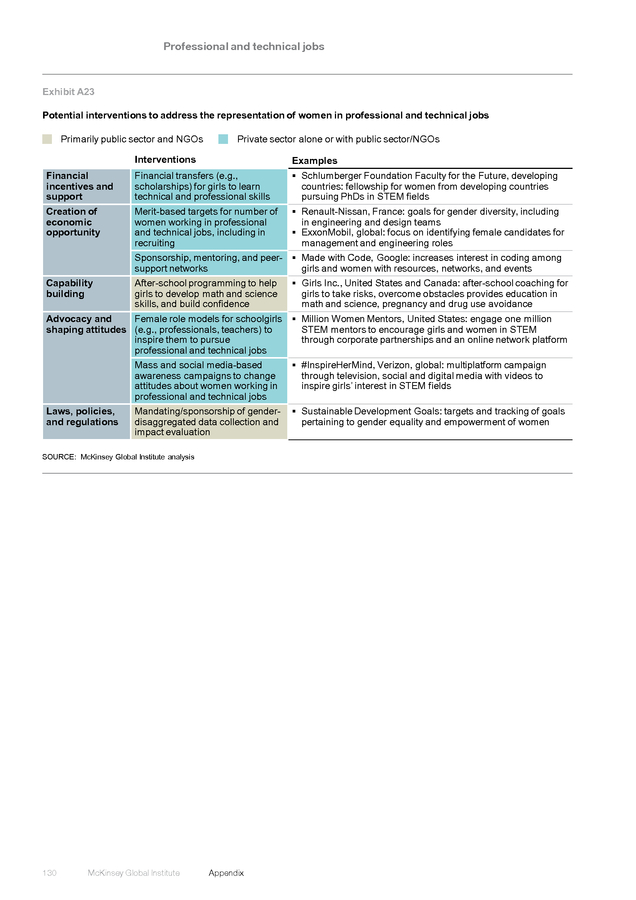

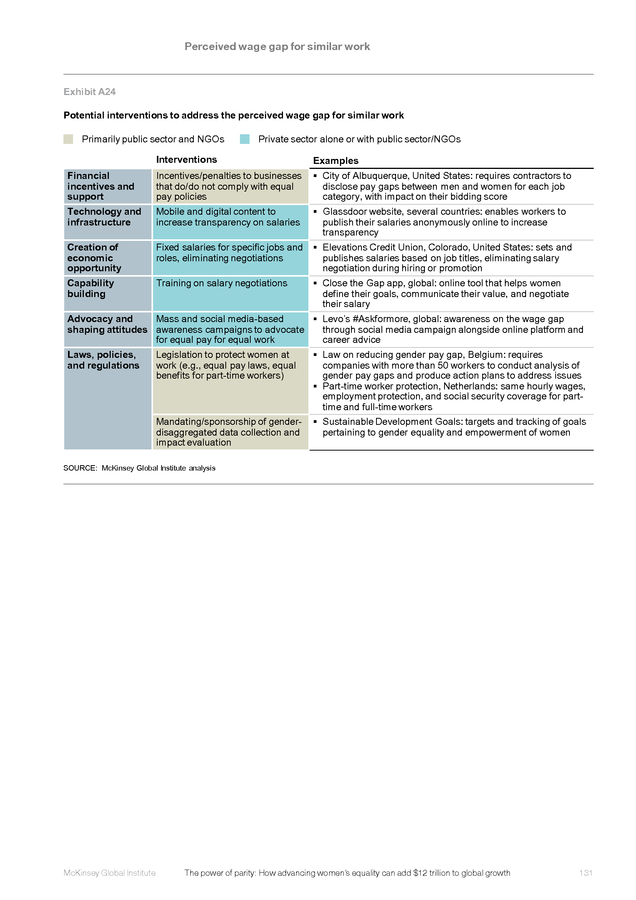

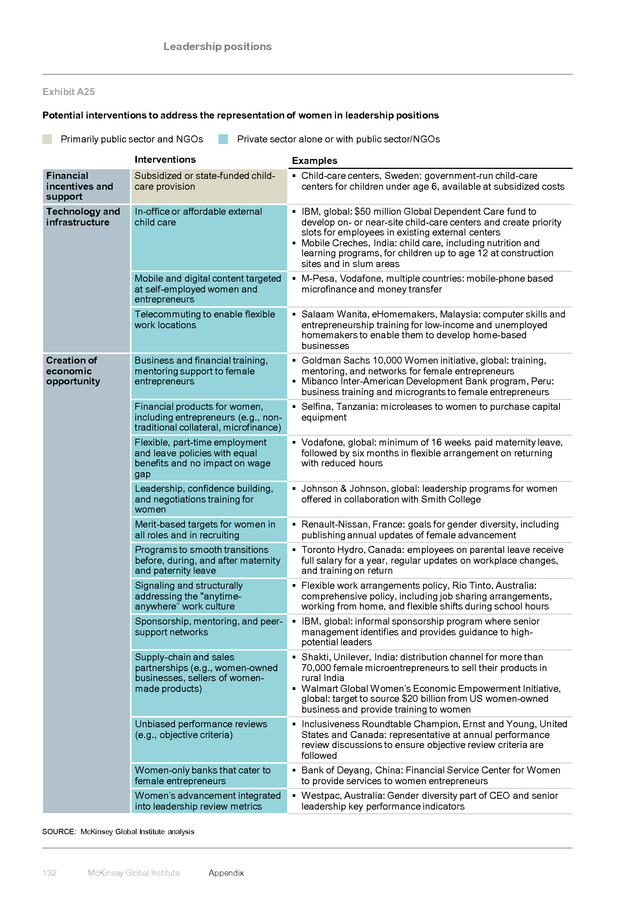

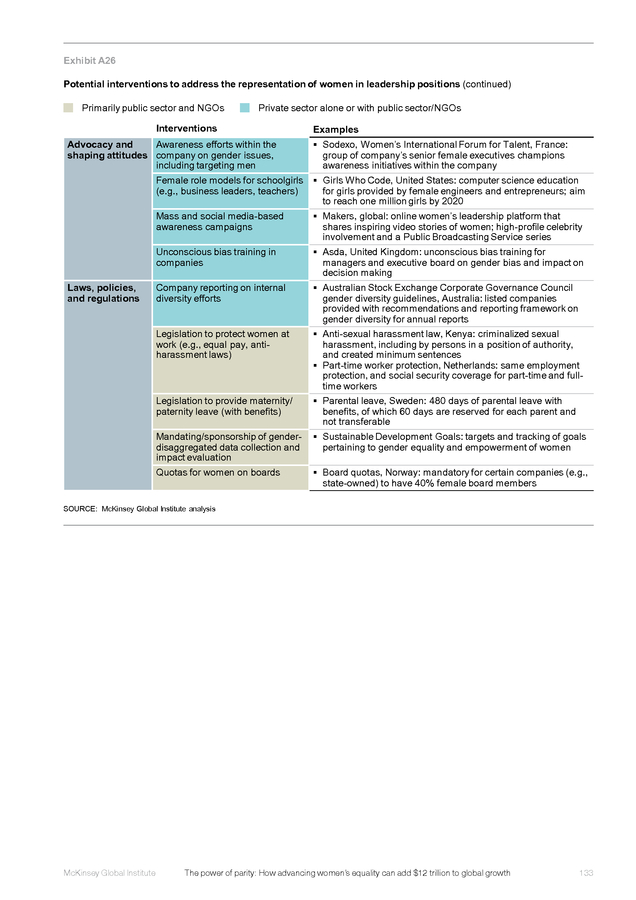

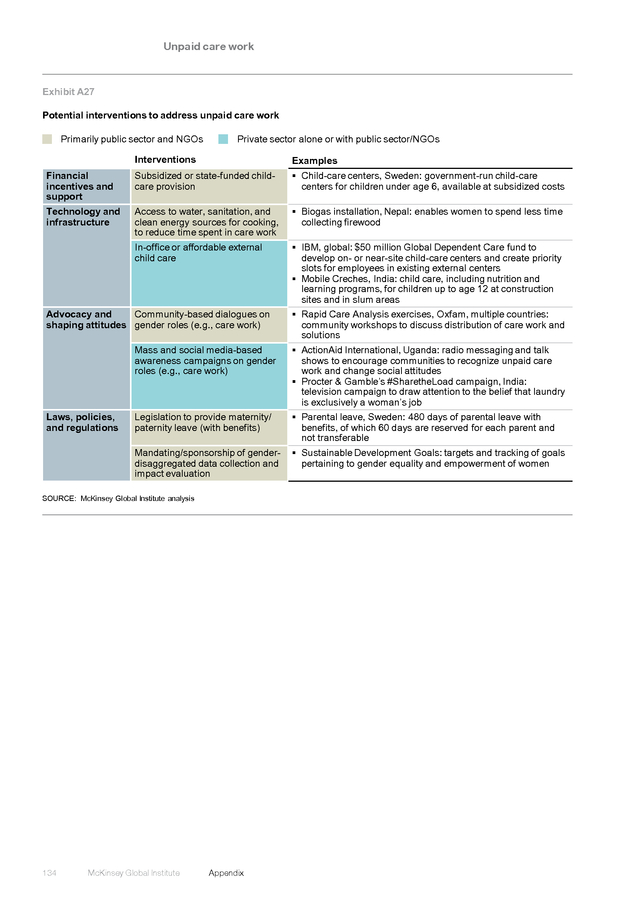

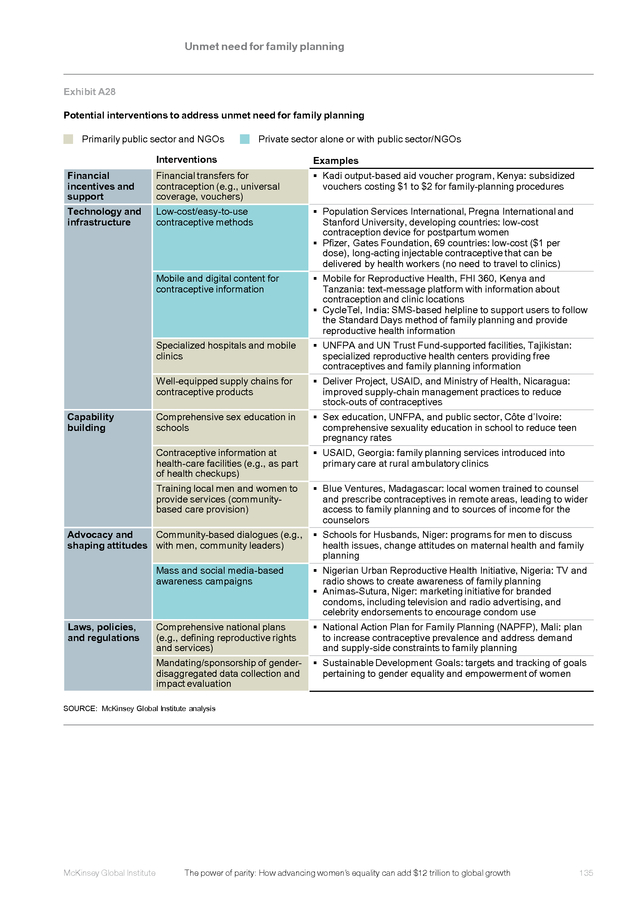

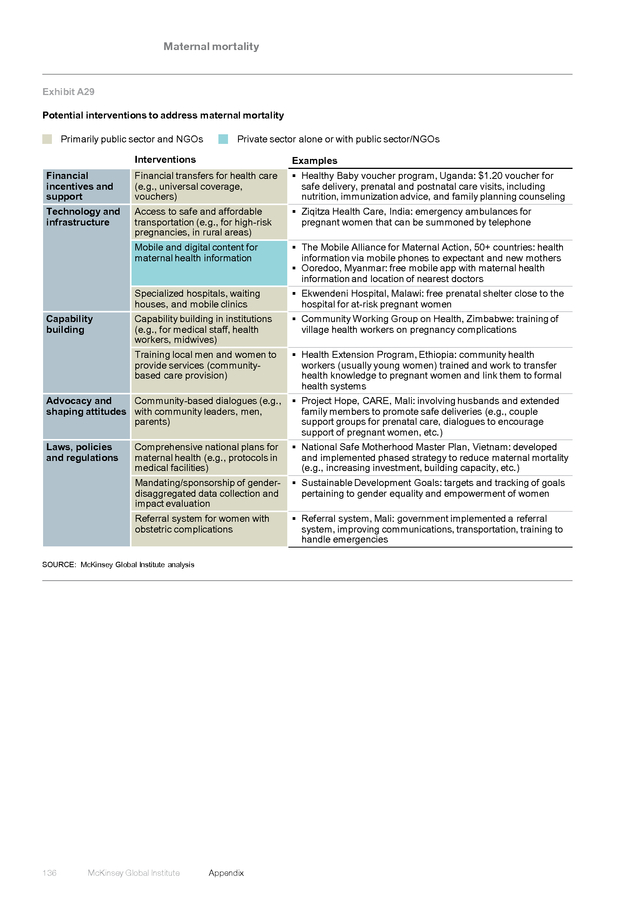

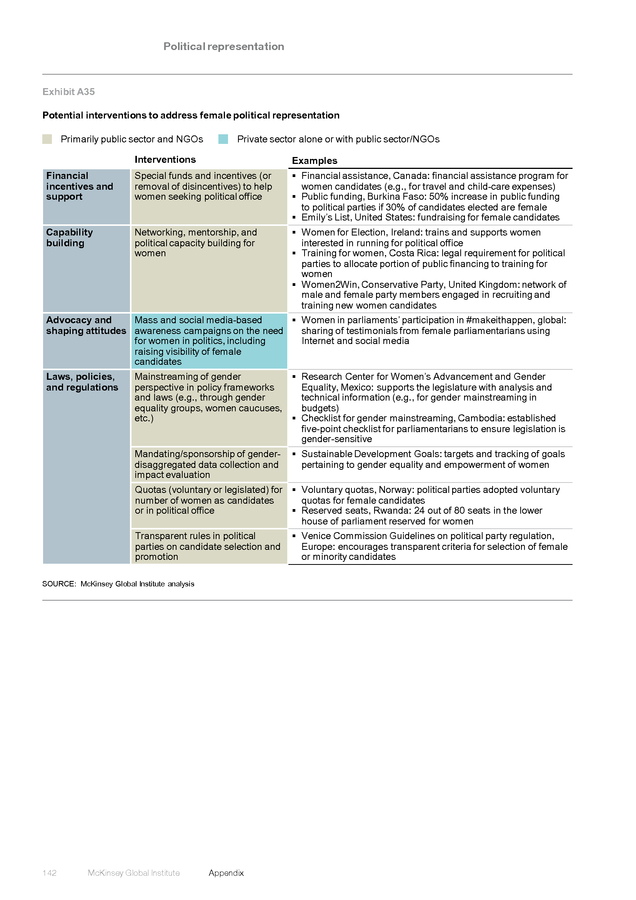

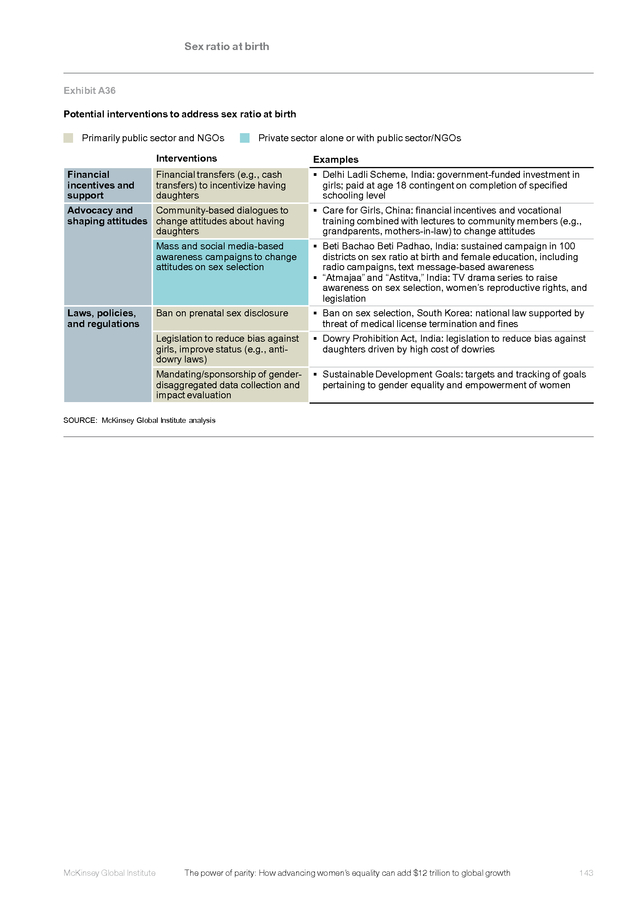

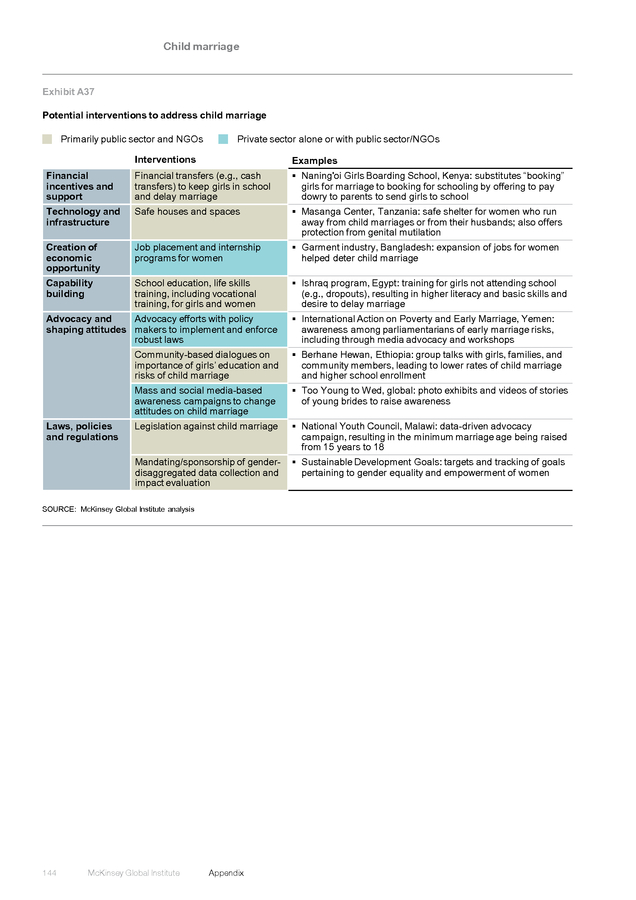

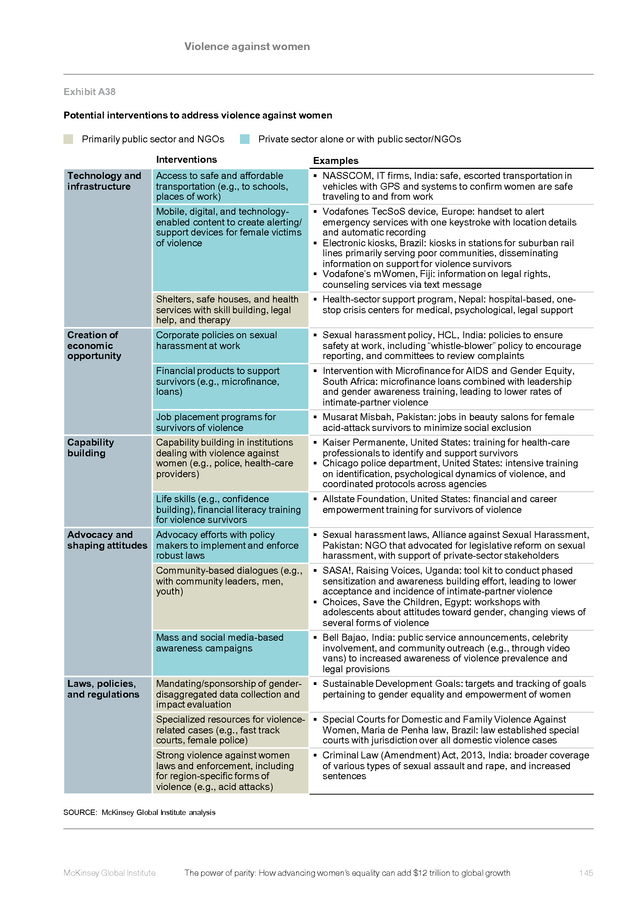

In many instances, the time scales involved before results can be discerned are long, and initiatives are often interrelated, complementing each other, and it is therefore not possible to disentangle the effects of one from another. We did not prioritize interventions because their impact can vary greatly depending on a country’s stage of development and culture. More analysis is required in order to tailor interventions to individual social contexts. We have grouped them into six promising types of intervention that stakeholders could explore to address gender gaps both in work and in society.

We believe these six offer a useful set of potential tools and approaches for tackling the ten impact zones. However, we do not believe that any single intervention is likely to have an impact on gender equality at a national level but rather that a comprehensive and sustained portfolio of initiatives will be required. ƒƒ Financial incentives and support. Financial mechanisms such as cash transfers targeting girls can help to incentivize behavioral changes within families and communities.

Morocco, for instance, implemented a program of cash transfers to families for educational spending that helped reduce dropout rates by about 75 percent and increased the rates of return to school of all children who had previously dropped out by about 80 percent.18 The Naning’oi Girls Boarding School project in Kenya substitutes the traditional practice of “booking” girls for marriage with booking them for school instead; in this program, the traditional dowry of livestock or gifts to the girl’s parents is given in exchange for her going to school rather than getting married.19 The removal of tax disincentives to both partners working can also help induce higher female labor-force participation. Canada reduced the tax contribution of the second earner in a family, and this resulted in an increase in labor-force participation for women.20 Universal publicly funded or subsidized child care has been the focus of governments in some countries. For instance, the Swedish government runs subsidized child-care centers for children below the age of six. More governments could offer such financial incentives and support, but companies can play a role too by, for instance, offering funding to school scholarship programs for girls and supporting movements in favor of the removal of tax disincentives to both partners working. ƒƒ Technology and infrastructure.

Investment in physical infrastructure, such as providing sanitation facilities for girls in schools, can reduce the gender gap in education. Egypt’s Education Enhancement program built schools in areas with low girls’ enrollment with the aim of increasing that enrollment. India’s IT and business-process outsourcing firms are providing safe transport for women employees using vehicles with tracking devices. Digital solutions such as mobile packages targeting women, apps designed for female entrepreneurs, and mobile-based emergency services for female victims of violence can reduce gender-based barriers in access to knowledge and opportunities, and provide support to women.

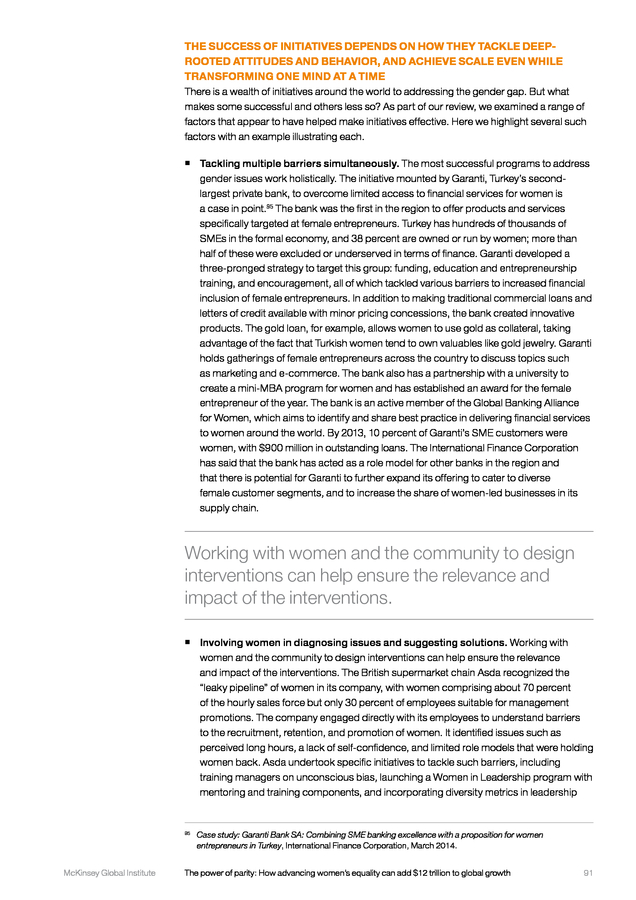

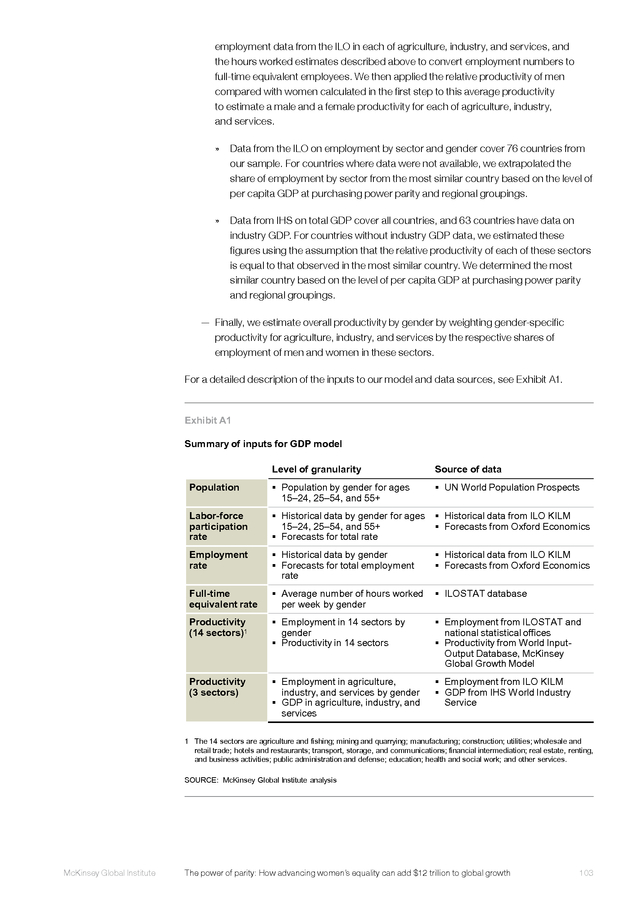

Examples of such solutions include Vodafone’s TecSoS handset that Najy Benhassine et al., Turning a shove into a nudge? A “labeled cash transfer” for education, NBER working paper number 19227, July 2013. 19 Saranga Jain and Kathleen Kurz, New insights on preventing child marriage: A global analysis of factors and programs, International Center for Research on Women, April 2007. 20 Evridiki Tsounta, Why are women working so much more in Canada? An international perspective, IMF working paper number 06/92, April 2006. 18 McKinsey Global Institute The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth 19 . alerts emergency services when a woman is subjected to violence; a single keystroke sends location details and triggers a recording of all activity near the device, information that can subsequently be used as evidence in court. Electronic kiosks in Brazil at stations on suburban rail lines that primarily serve poor communities disseminate information on support for violence survivors. Infrastructure that provides energy and water in homes, and affordable child-care centers can reduce time spend on unpaid work. ƒƒ Creation of economic opportunity. Opening up avenues for women to engage in productive work and entrepreneurship, and lowering barriers to their moving into positions of responsibility and leadership are areas where the private sector can play a particularly effective role.