Description

A LABOR MARKET THAT WORKS:

CONNECTING TALENT WITH

OPPORTUNITY IN THE

DIGITAL AGE

JUNE 2015

HIGHLIGHTS

29

Better, faster matching

41

Economic impact

57

Talent management

for companies

. In the 25 years since its founding, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) has sought to develop

a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. As the business and economics

research arm of McKinsey & Company, MGI aims to provide leaders in the commercial,

public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and

policy decisions.

MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the

analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro”

methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad

macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports

have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries.

Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth, natural resources, labor markets, the evolution of global financial markets, the economic impact of technology and innovation, and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed global flows; the economies of Brazil, Mexico, Nigeria, and Japan; China’s digital transformation; India’s path from poverty to empowerment; affordable housing; the effects of global debt; and the economics of tackling obesity. MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company directors: Richard Dobbs, James Manyika, and Jonathan Woetzel. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, and Jaana Remes serve as MGI partners. Project teams are led by the MGI partners and a group of senior fellows, and include consultants from McKinsey & Company’s offices around the world. These teams draw on McKinsey & Company’s global network of partners and industry and management experts. In addition, leading economists, including Nobel laureates, act as research advisers. The partners of McKinsey & Company fund MGI’s research; it is not commissioned by any business, government, or other institution.

For further information about MGI and to download reports, please visit www.mckinsey.com/mgi. Copyright © McKinsey & Company 2015 . A LABOR MARKET THAT WORKS: CONNECTING TALENT WITH OPPORTUNITY IN THE DIGITAL AGE JUNE 2015 James Manyika | San Francisco Susan Lund | Washington, DC Kelsey Robinson | San Francisco John Valentino | Silicon Valley Richard Dobbs | London . PREFACE In advanced and emerging economies alike, individuals are struggling to find work and build careers that make use of their skills and capabilities. The strains in global labor markets have been worsening for decades, and the challenges have been magnified in the aftermath of the global recession. In many countries, concerns about employment have been exacerbated by long-term trends of stagnant wage growth and automation. But at the same time, there has been a constant refrain from employers about the difficulties of finding talent with the right skills.

The growing use of online talent platforms may begin to address these problems—and even to swing the pendulum slightly in favor of workers by empowering them with broader choices, more mobility, and more flexibility. These tools are fundamentally altering the way individuals go about searching for work and the way many employers approach hiring. The power of a digital platform is not always apparent until it reaches a certain critical mass. Online talent platforms appear to be approaching exactly that sort of tipping point. As these platforms rapidly expand the size of their user networks and the volume of data they can synthesize, the cumulative benefits are growing larger.

We believe there is potential for online talent platforms to create real macroeconomic impact in the years ahead—and as these technologies continue to evolve, they may change the world of work in ways that we can only begin to imagine today. This research aims to build a deeper understanding of how these platforms can affect labor markets, although it does not attempt to address the many broader issues affecting employment prospects, including wage stagnation, automation, and aggregate demand. This project builds on a body of previous McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) research studies on labor markets, including The world at work: Jobs, pay, and skills for 3.5 billion people; Help wanted: The future of work in advanced economies; and An economy that works: Job creation and America’s future. It also continues our efforts to analyze the economic impact of the Internet and new digital technologies, which has formed the basis of recent MGI reports on topics such as big data, open data, social technologies, and the Internet of Things. This research was led by James Manyika, an MGI director based in San Francisco, and Susan Lund, an MGI partner based in Washington, DC.

The project team, led by John Valentino and Kelsey Robinson, included Malte Bedürftig, Kathy Gerlach, Liz Kuenstner, and Amber Yang. Richard Dobbs, an MGI director based in London; Jacques Bughin, a McKinsey director based in Brussels; and Michael Chui, an MGI partner based in San Francisco, supplied valuable feedback and insight. Lisa Renaud and Peter Gumbel provided editorial support.

Many thanks go to our colleagues in operations, production, and external relations, including Marisa Carder, Matt Cooke, Vanessa Gotthainer, Deadra Henderson, Julie Philpot, and Rebeca Robboy. Numerous insights and challenges from our academic advisers enriched this report. We extend sincere thanks to Martin N. Baily, the Bernard L. Schwartz Chair in Economic Policy Development at the Brookings Institution; Erik Brynjolfsson, the Schussel Family Professor of Management Science, professor of information technology, and director of the MIT .

Center for Digital Business at the MIT Sloan School of Management; Michael Spence, Nobel laureate and William R. Berkley Professor in Economics and Business at NYU Stern School of Business; and Laura Tyson, S. K. and Angela Chan professor of Global Management at Haas School of Management, University of California at Berkeley. This project benefited immensely from the expertise of McKinsey colleagues around the world, including members of the Firm’s High Tech Practice, the Organization Practice, and MGI.

We thank Bruce Fecheyr-Lippens, Bryan Hancock, Paige Harazin-Masi, Jordan Jaffee, Jocelene Kwan, Meredith Lapointe, Xiujun Lillian Li, Anu Madgavkar, Sree Ramaswamy, and Bill Schaninger. This independent MGI initiative is based on our own research, the experience of our McKinsey colleagues more broadly, and McKinsey’s Technology, Media & Telecom Practice and its collaboration with LinkedIn, which included data and insights from Reid Hoffman, Allen Blue, Jeff Weiner, Laura Dholakia, Brian Rumao, Pablo Chavez, Hani Durzy, Erin Hosilyk, Giovanni Iachello, Andrew Kritzer, Igor Perisic, James Raybould, Christine Schmidt, Dan Shapero, and Boyu Zhang. In addition, this project benefited from input provided by other industry and academic researchers as well as data from Burning Glass. We thank Jonathan Hall of Uber; Gad Levanon of The Conference Board; Michael Mandel of the Progressive Policy Institute; Max Simkoff of Evolv; and Hal Varian of Google.

In addition, we are grateful to Zoë Baird, Philip D. Zelikow, and others at the Markle Foundation’s Rework America initiative (of which we have been a part). We appreciate their insights regarding employment and skills in the digital age. This report contributes to MGI’s mission to help business and policy leaders understand the forces transforming the global economy, identify strategic locations, and prepare for the next wave of growth. As with all MGI research, this work is independent and has not been commissioned or sponsored in any way by any business, government, or other institution. We welcome your comments on the research at MGI@mckinsey.com. Richard Dobbs Director, McKinsey Global Institute London James Manyika Director, McKinsey Global Institute San Francisco Jonathan Woetzel Director, McKinsey Global Institute Shanghai June 2015 .

© ??? Images Getty . CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS In brief 29 Executive summary Page 1 1. The disconnect between workers and work Page 17 2. Online talent platforms transform the job market Page 29 Benefits for workers 3. The economic potential of online talent platforms Page 41 41 4.

Talent management for companies Page 57 5. Capturing the opportunity Page 73 Bibliography Page 81 Benefits for the broader economy 57 Benefits for companies A complete technical appendix describing the methodology and data sources used in this research and a separate appendix of country insights are available at www.mckinsey.com/mgi. . IN BRIEF A LABOR MARKET THAT WORKS: CONNECTING TALENT WITH OPPORTUNITY IN THE DIGITAL AGE Labor markets around the world have not kept pace with rapid shifts in the global economy, and their inefficiencies take a heavy toll. Millions of people cannot find work, yet sectors from technology to health care cannot find people to fill open positions. Many who do work feel overqualified or underutilized. Online talent platforms can ease a number of these dysfunctions by more effectively connecting individuals with work opportunities. They include websites (such as Monster.com and LinkedIn) that aggregate individual resumes with job postings from traditional employers as well as the rapidly growing number of digital marketplaces for services, such as Uber and Upwork.

Even if these platforms touch only a fraction of the global workforce, they can generate significant benefits for economies and for individuals. While their growth and adoption has been dramatic, they are still evolving in terms of capabilities and potential. ƒƒ In countries around the world, 30 to 45 percent of the working-age population is unemployed, inactive in the workforce, or working only part-time. In the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, India, Brazil, and China, this amounts to 850 million people. ƒƒ Online talent platforms serve as clearinghouses that can inject new momentum into job markets.

By 2025, we calculate they could add $2.7 trillion, or 2.0 percent, to global GDP and increase employment by 72 million full-time-equivalent positions. ƒƒ Up to 540 million individuals could benefit from online talent platforms by 2025. As many as 230 million could shorten search times between jobs, reducing the duration of unemployment, while 200 million who are inactive or working part-time could work additional hours through freelance platforms. As many as 60 million people could find work that more closely suits their skills or preferences, and another 50 million could shift from informal to formal employment. ƒƒ Countries with persistently high unemployment and low participation, such as South Africa, Spain, and Greece, would potentially benefit most.

Among advanced economies, the United States stands to realize significant gains because of the relative fluidity of its job market. By contrast, the relative potential is lower in Japan and China due to low unemployment and other barriers that limit adoption. ƒƒ Online talent platforms create transparency around the demand for skills, enabling young people to make more informed educational choices. This can create an opportunity to improve the allocation of some $89 billion in annual spending on tertiary education in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, India, Brazil, and China. ƒƒ Companies can use online talent platforms to identify and recruit candidates—and then to motivate them and help them become more productive once they start work.

We calculate that adoption could increase output by up to 9 percent and reduce costs related to talent and human resources by as much as 7 percent. Capturing this potential will require expanded broadband access, updated labor market regulations, systems for delivering worker benefits, and clearer data ownership and privacy rules. There is also an enormous opportunity to harness the data being gathered by these platforms to produce insights into the demand for specific skills and occupations as well as the career outcomes associated with particular educational institutions and programs. More accurate and predictive modeling could help individuals make more informed decisions about education, training, and career paths. .

A labor market that works: Connecting talent with opportunity in the digital age 63% 30-50% of the working-age 40% population is inactive, unemployed, or working part-time... 40% 24% .br .us .de .cn ...yet large shares of employers say they can’t fill positions Online talent platforms: . Match people . Help ï¬rms hire and . Create marketplaces .

Reveal trends in the manage talent and jobs for freelance work demand for skills Potential impact by 2025 $2.7 trillion 540 million 275 bps in annual global GDP (equivalent to the GDP of the United Kingdom) individuals around the world could benefit average improvement in company profit margins The long-term opportunity: Harnessing data to inform education and career choices 101010101001010010110 10101001011001010010110 10101010100101010010110 01010101010001010010110 10101010101101010010110 101010101001010010110 10101001011001010010110 10101010100101010010110 01010101010001010010110 10101010101101010010110 . © Getty Images . EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Technology and globalization have created a more dynamic and fast-paced business environment, but the way economies connect most individuals with work has been slow to respond. Millions are unable to find jobs, even as companies report that they cannot find the people they need. Meanwhile, a significant proportion of workers feel overqualified or disengaged in their current roles. These issues translate into costly wasted potential for the global economy.

But more importantly, they represent hundreds of millions of people coping with unemployment, underemployment, stagnant wages, and discouragement. Labor markets are ripe for transformation, and it is finally arriving—in the form of digital platforms, the very same technologies that have reshaped the business and consumer environment in areas such as e-commerce. Online talent platforms are marketplaces and tools that can connect individuals to the right work opportunities. The sheer size of their user networks expands the pool of possibilities, and their powerful search capabilities and algorithms filter those possibilities in an efficient and personalized way. These platforms are rapidly evolving in scope and will continue to do so in the years ahead. $2.7T potential increase in annual global GDP Some, such as Monster.com and LinkedIn, match job seekers and traditional employers. These platforms help individuals showcase their skills, availability, and other traits to a wider set of potential employers; they also equip them with better information about opportunities and career paths.

Others match customers with contingent workers who are available to perform specific tasks or services, in specific times and places. These may involve freelancers with esoteric skills performing knowledge work or individuals with no credentials driving passengers or doing household chores. Freelancing is not a new concept; many professionals, from editors to accountants, have traditionally chosen to operate on a selfemployed, project basis.

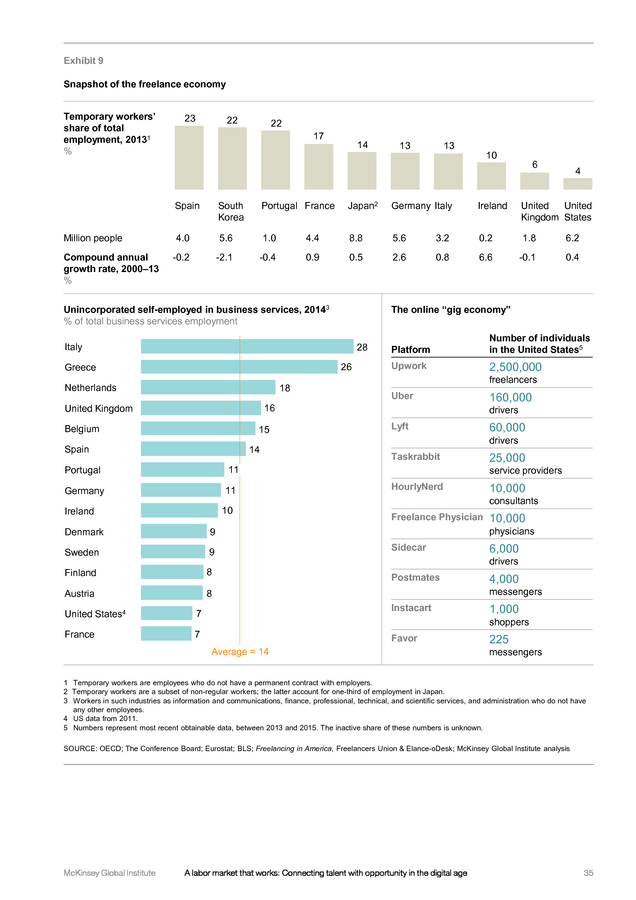

Even today contingent workers account for only a small fraction of the overall labor force in advanced economies. But new online marketplaces that facilitate transactions in a wide range of services are growing rapidly, giving rise to what some have called the “gig economy.”1 Online talent platforms have already attracted hundreds of millions of users around the world. As they grow in scale, they are becoming faster and more effective clearinghouses that can inject momentum and transparency into job markets while drawing in new participants.

This research examines their potential to create economic impact by addressing some longstanding challenges in labor markets. By 2025, our supply-side analysis shows that online talent platforms could raise global GDP by up to $2.7 trillion and increase employment by 72 million full-time-equivalent positions. The actual number of individuals who stand to gain is much larger. In total, some 540 million people—a number equivalent to the entire population of the European Union—could find employment, increase the number of hours they work, or find jobs that are a better fit. Beyond their impact on individuals and the broader economy, talent platforms can help companies transform the way they hire, train, and manage their employees.

The early 1 We define the “gig economy” as contingent work that is transacted on a digital marketplace. This definition excludes ongoing part-time employment and freelance work that is not contracted on an online talent platform. . adopters are discovering that better-informed decisions about human capital produce better business results. In addition, talent platforms could improve signaling about the skills that are actually in demand across the economy. As this information shapes decisions about education and training, the entire skills mix of the economy could adjust more accurately over time. Online talent platforms will not sweep away all the roadblocks that impede the smooth functioning of labor markets. They cannot, for example, address weak aggregate demand or create better-quality jobs across the board.

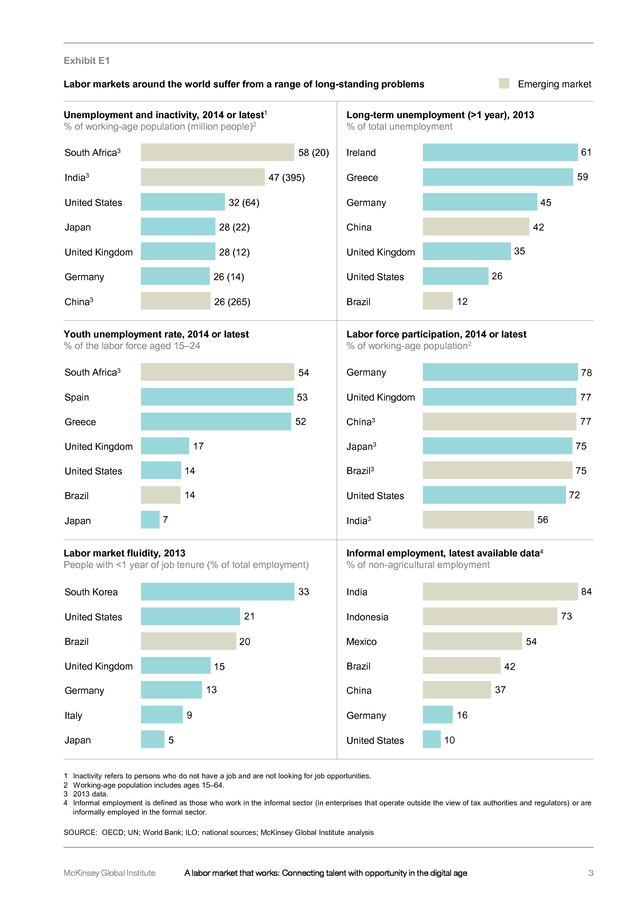

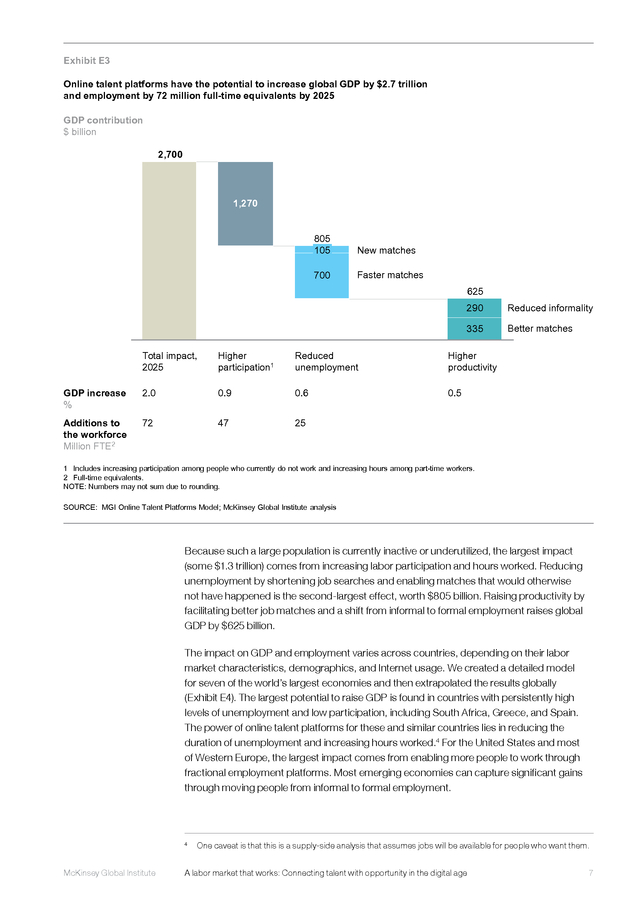

But they can make a much-needed difference in how well economies perform one of their most basic tasks: connecting individuals with productive and fulfilling work. There is a stubborn disconnect between people and jobs Labor markets around the world suffer from a range of inefficiencies that pose hurdles for individuals while lowering overall employment and productivity (Exhibit E1). The Great Recession exacerbated these issues, but they are not simply a reflection of the business cycle. In many countries, labor markets have been deteriorating for decades. First, there are growing problems matching jobs and workers.

The skills that many workers have may not match the opportunities at hand, information gaps may prevent qualified job seekers from ever learning about promising openings, or the right workers may be in the wrong geographies. While economists debate whether there is evidence of a skills gap for the aggregate economy (given that wages have not been rising), employers have no doubt that filling specific roles that require specific skills is often difficult. In a 2014 Manpower survey of 37,000 employers around the world, 36 percent said they could not find the talent they needed.

Shortages of software engineers and big data analysts often make the headlines, but a wide range of talent can be hard to find, including electricians, welders, commercial drivers, and health-care workers. 30-45% of the global working-age population is unemployed, inactive, or part-time At the same time, 30 to 45 percent of the working-age population in countries around the world goes underutilized—meaning they are unemployed, inactive, or working only parttime. This translates into some 850 million people in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, Brazil, China, and India alone. While some have opted out of the workforce by choice or prefer part-time employment, this number includes many millions who would like the means to raise their incomes.

Youth unemployment is an alarming aspect of this underutilization. Almost 75 million youth are officially unemployed, but hundreds of millions more are inactive (that is, not involved in education, employment, or training). Without a solid start to propel their careers forward, their economic prospects will be lower over their entire lifetimes. Even those who do have jobs may not be realizing their full potential.

Many college graduates, for example, hold jobs that do not require their degrees. Thirty-seven percent of global respondents to a recent survey of job seekers conducted by LinkedIn said their current job does not fully utilize their skills or provide enough challenge. Without real engagement, boredom and frustration set in, and productivity suffers. Low and declining labor market fluidity compounds the problem.

When people switch jobs voluntarily, they often find work that better suits them—and they typically garner higher wages in the process. But the rate of job changing is limited in most mature economies and has fallen sharply in the United States. A more rigid labor market also limits the opportunities available to the unemployed and to new entrants to the workforce. 2 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary .

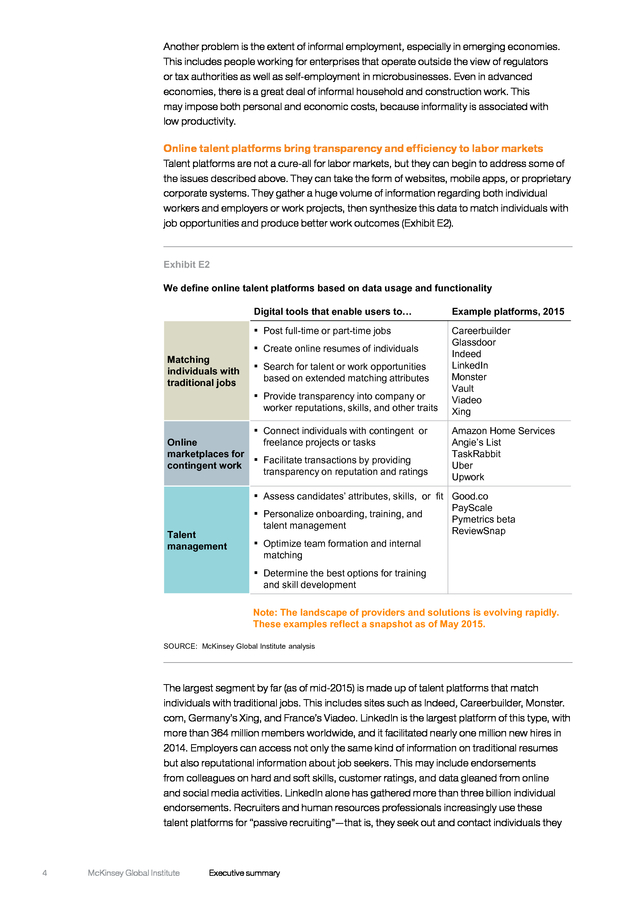

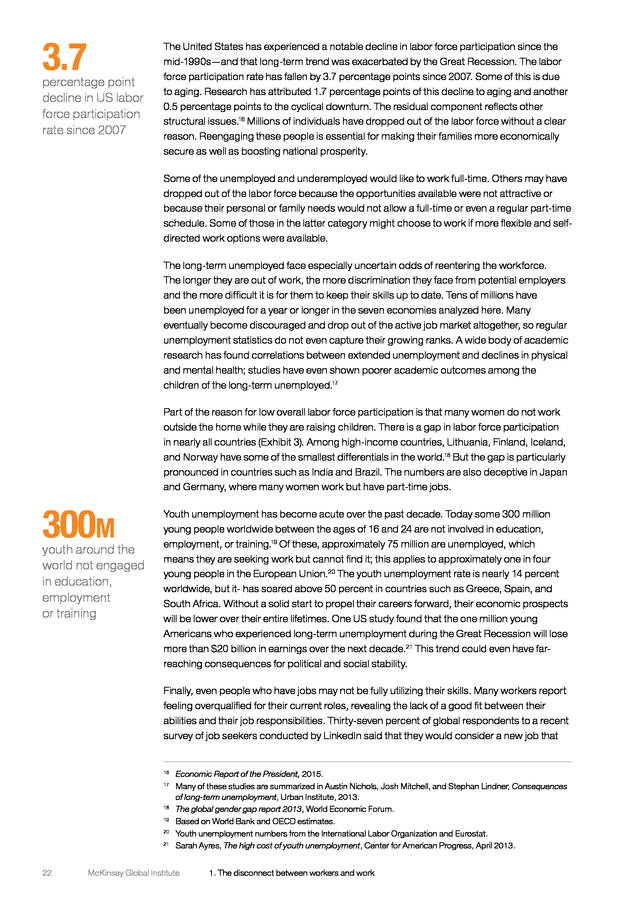

Exhibit E1 Labor markets around the world suffer from a range of long-standing problems Unemployment and inactivity, 2014 or latest1 % of working-age population (million people)2 Long-term unemployment (>1 year), 2013 % of total unemployment 58 (20) South Africa3 47 (395) India3 United States Emerging market 32 (64) 61 Ireland 59 Greece Germany Japan 28 (22) China United Kingdom 28 (12) 45 United Kingdom Germany 26 (14) 26 (265) 35 26 United States China3 42 Brazil Youth unemployment rate, 2014 or latest % of the labor force aged 15–24 12 Labor force participation, 2014 or latest % of working-age population2 South Africa3 54 Germany 78 Spain 53 United Kingdom 77 Greece 52 China3 77 17 United Kingdom Japan3 75 75 United States 14 Brazil3 Brazil 14 United States Japan 7 33 South Korea 21 United States Brazil 20 United Kingdom 15 13 Germany 9 Italy 1 2 3 4 56 India3 Labor market fluidity, 2013 People with <1 year of job tenure (% of total employment) Japan 72 5 Informal employment, latest available data4 % of non-agricultural employment 84 India 73 Indonesia Mexico 54 Brazil 42 37 China 16 Germany United States 10 Inactivity refers to persons who do not have a job and are not looking for job opportunities. Working-age population includes ages 15–64. 2013 data. Informal employment is defined as those who work in the informal sector (in enterprises that operate outside the view of tax authorities and regulators) or are informally employed in the formal sector. SOURCE: OECD; UN; World Bank; ILO; national sources; McKinsey Global Institute analysis McKinsey Global Institute A labor market that works: Connecting talent with opportunity in the digital age 3 . Another problem is the extent of informal employment, especially in emerging economies. This includes people working for enterprises that operate outside the view of regulators or tax authorities as well as self-employment in microbusinesses. Even in advanced economies, there is a great deal of informal household and construction work. This may impose both personal and economic costs, because informality is associated with low productivity. Online talent platforms bring transparency and efficiency to labor markets Talent platforms are not a cure-all for labor markets, but they can begin to address some of the issues described above. They can take the form of websites, mobile apps, or proprietary corporate systems.

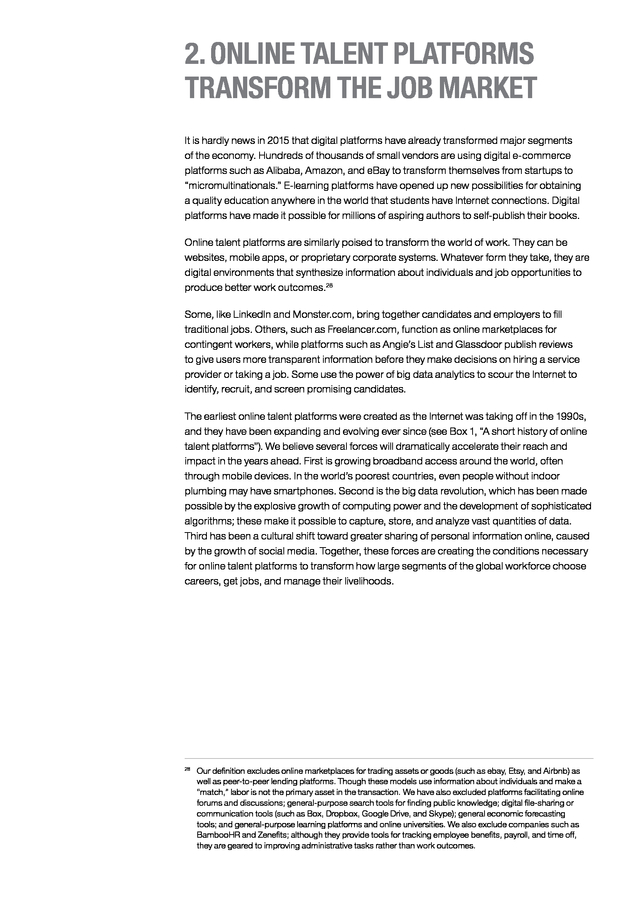

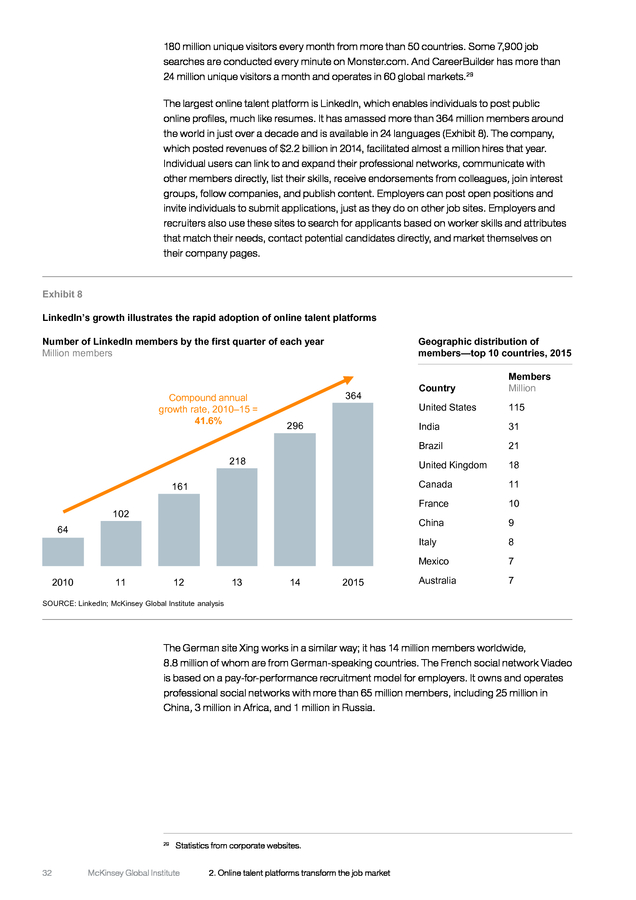

They gather a huge volume of information regarding both individual workers and employers or work projects, then synthesize this data to match individuals with job opportunities and produce better work outcomes (Exhibit E2). Exhibit E2 We define online talent platforms based on data usage and functionality Digital tools that enable users to… â–ª Post full-time or part-time jobs Matching individuals with traditional jobs Example platforms, 2015 Careerbuilder Glassdoor Indeed LinkedIn Monster Vault Viadeo Xing â–ª Create online resumes of individuals â–ª Search for talent or work opportunities based on extended matching attributes â–ª Provide transparency into company or worker reputations, skills, and other traits Online marketplaces for contingent work â–ª Connect individuals with contingent or freelance projects or tasks â–ª Facilitate transactions by providing transparency on reputation and ratings Amazon Home Services Angie’s List TaskRabbit Uber Upwork â–ª Assess candidates’ attributes, skills, or fit Good.co â–ª Personalize onboarding, training, and Talent management talent management â–ª Optimize team formation and internal PayScale Pymetrics beta ReviewSnap matching â–ª Determine the best options for training and skill development Note: The landscape of providers and solutions is evolving rapidly. These examples reflect a snapshot as of May 2015. SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis The largest segment by far (as of mid-2015) is made up of talent platforms that match individuals with traditional jobs. This includes sites such as Indeed, Careerbuilder, Monster. com, Germany’s Xing, and France’s Viadeo. LinkedIn is the largest platform of this type, with more than 364 million members worldwide, and it facilitated nearly one million new hires in 2014.

Employers can access not only the same kind of information on traditional resumes but also reputational information about job seekers. This may include endorsements from colleagues on hard and soft skills, customer ratings, and data gleaned from online and social media activities. LinkedIn alone has gathered more than three billion individual endorsements.

Recruiters and human resources professionals increasingly use these talent platforms for “passive recruiting”—that is, they seek out and contact individuals they 4 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary . want rather than placing an ad and waiting to see who responds. This trend favors highly specialized talent in fast-growing industries. Another category of online talent platforms connects contingent workers with specific tasks or assignments. Although the number of people employed on such platforms is small today (accounting for less than 1 percent of the US working-age population by our estimate), these are growing rapidly. Traditional employers and startups can use these platforms to call in specialists for an assignment on short notice.

Upwork (formerly Elance-oDesk), for example, has created online marketplaces connecting some four million businesses with more than nine million freelancers from 180 countries, performing tasks such as web development, graphic design, and marketing. Freelance platforms can improve the ability of these workers to market their skills more widely and find new clients. Some of these platforms are aimed at consumers rather than companies.

Individuals can turn to TaskRabbit and Amazon Home Services, among others, to hire someone nearby for errands or home repairs. A growing number of these platforms deliver one type of specialized service, such as Uber, Lyft, and Sidecar for taxi services and UrbanSitter and Care.com for child care. The quality of jobs being created through these on-demand service platforms is coming under increased scrutiny. For some workers, participation in contingent work may be their only option for getting by in a difficult labor market.

But there is growing evidence that many use them to supplement income from other jobs. The availability of more flexible and self-directed options can also boost participation among people who are out of the workforce altogether. Online talent platforms offer a number of other benefits to individual workers. The availability of comprehensive online job listings provides them with more options and a better understanding of the wages they can command on the open market.

Voluntary job changes are correlated with higher wages—so a more dynamic job market creates more opportunity for workers to move up the pay scale while moving into new roles.2 Talent platforms such as Glassdoor and Vault gather anonymous reviews and salary information provided by current and former employees of specific organizations; this offers individuals new visibility into what it would be like to work for a given company, increasing the odds that they will choose a work environment they will enjoy. Over time, new capabilities are emerging that have the potential to help a much wider range of people. Talent platforms are uniquely positioned to track the positions that employers are filling, the skills required, and career pathways that take people from education and entry-level positions into more fulfilling work. They can empower individuals—from high school students to workers seeking a mid-career change—with better information about educational investment and training. It is important to note that the individual platforms, companies, and functionalities described in this report represent a snapshot of where this fast-moving field stands in 2015.

These are early days, and as talent platforms evolve, they may grow tremendously in scope. Consider how digital platforms expanded in areas such as e-commerce. Amazon, for instance, started as an online bookseller but has introduced innovations and business lines that have sent ripple effects through multiple industries; few anticipated these developments in the company’s early years.

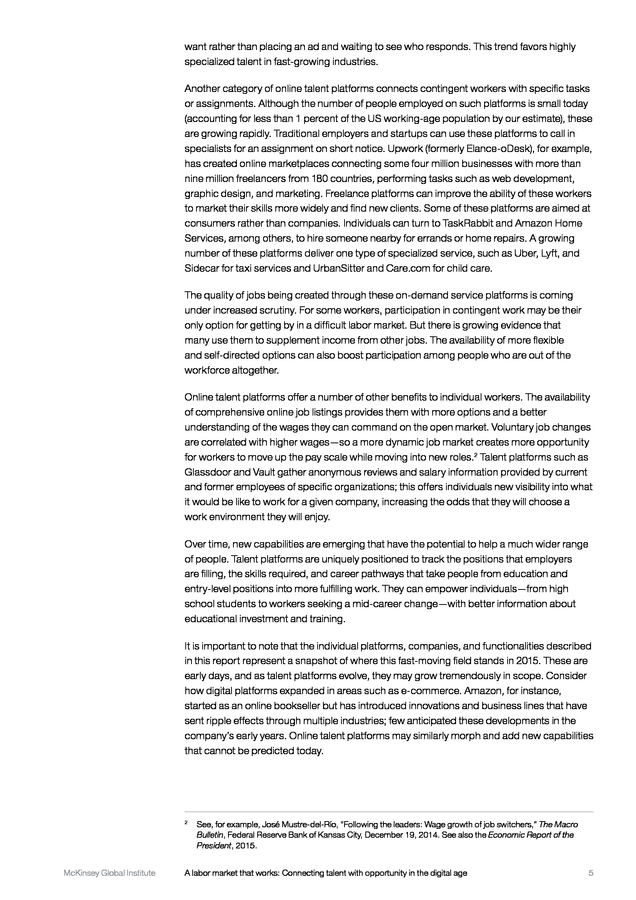

Online talent platforms may similarly morph and add new capabilities that cannot be predicted today. 2 McKinsey Global Institute See, for example, José Mustre-del-Río, “Following the leaders: Wage growth of job switchers,” The Macro Bulletin, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, December 19, 2014. See also the Economic Report of the President, 2015. A labor market that works: Connecting talent with opportunity in the digital age 5 . Online talent platforms can support economic growth and improve work outcomes for millions of individuals As these platforms continue to attract more participants and employers, their impact on the broader economy could be significant. We assess this potential at several levels: the direct impact on raising global GDP and employment; the indirect benefit from reducing spending on unemployment benefits and misallocations in education programs; and dynamic longterm benefits such as enhanced innovation and creative destruction. Contributing $2.7 trillion to global GDP annually by 2025 To calculate the potential effects on GDP and employment, we analyze three channels of impact: increasing labor force participation, reducing unemployment, and raising labor productivity. In each of these areas, we make projections based on early empirical evidence that has been scaled up using modest assumptions. Our projections look at 2025, when Internet penetration will be higher and talent platforms will have evolved to a substantial degree.

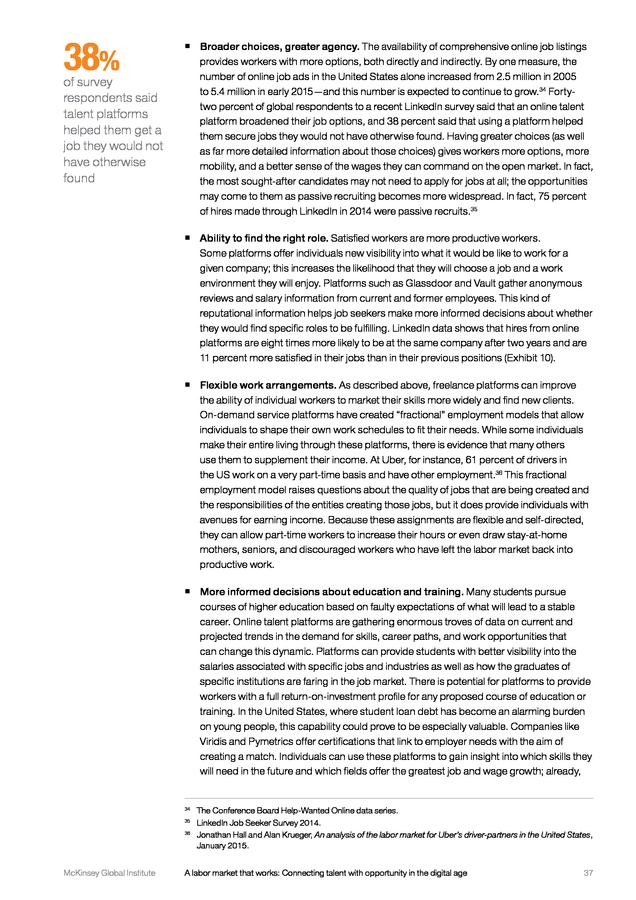

It is also important to note that our model also assumes that economies will have fully recovered from the Great Recession, with no slack in aggregate demand or the labor market; this implies there are jobs available for anyone who wants to work. ƒƒ Increasing labor force participation and hours worked among part-time employees. There is evidence from around the world that some people would work more hours if they could. A US survey, for example, reports that three-quarters of stayat-home mothers would be likely to work if they had flexible options.3 A 2015 global survey by LinkedIn found that almost 40 percent of respondents who work part-time would increase their hours for a proportionate pay increase.

The flexible employment model created by new digital marketplaces for contingent work can appeal to people who do not want traditional full-time positions—and if even a small fraction of inactive youth and adults use these platforms to work a few hours per week, the economic impact would be huge. ƒƒ Reducing unemployment. With their powerful search capabilities and sophisticated screening algorithms, online talent platforms can speed the hiring process and cut the time individuals spend searching between jobs. By aggregating data on candidates and job openings across entire countries or regions, they may address some geographic mismatches and enable matches that otherwise would not have been made.

People who have felt trapped in stagnant local economies can gain insight into the opportunities they could realize by moving even a few hundred miles. This dynamic could be especially important for workers across Europe, where employment prospects differ radically from country to country. ƒƒ Raising labor productivity. Online talent platforms help put the right people in the right jobs, thereby increasing their productivity along with their job satisfaction.

There are also large productivity gains to be captured from drawing people who are engaged in informal work into formal employment, especially in emerging economies. Both of these effects could increase output per worker, raising global GDP. The model results show that by 2025, even with conservative assumptions, online talent platforms could increase global GDP by $2.7 trillion annually—an impact that is equivalent to the entire GDP of the United Kingdom (Exhibit E3). This would represent an increase of 2.0 percent over current projections for world GDP in that year. Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times/CBS News poll of 1,002 non-employed US adults, December 2014. 3 6 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary .

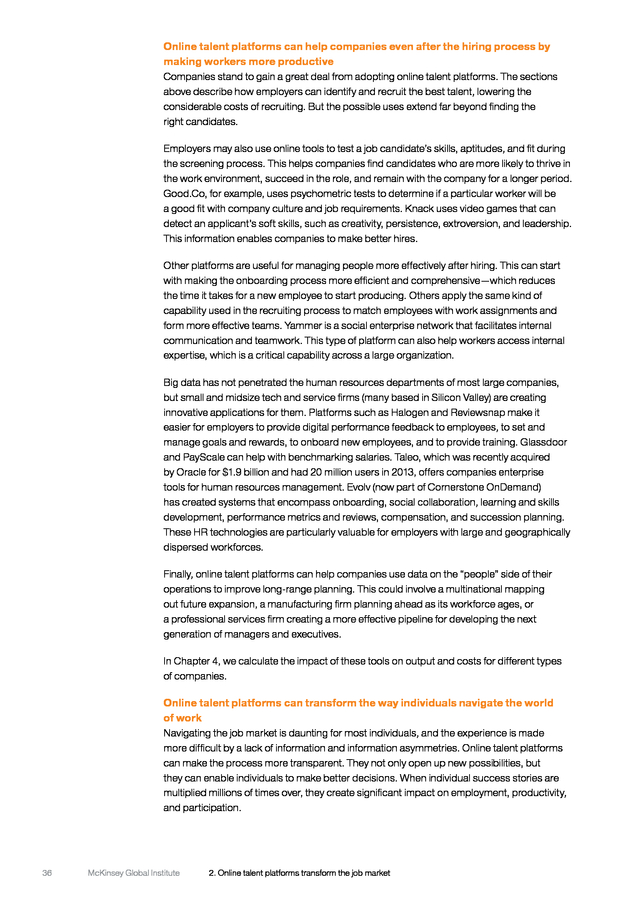

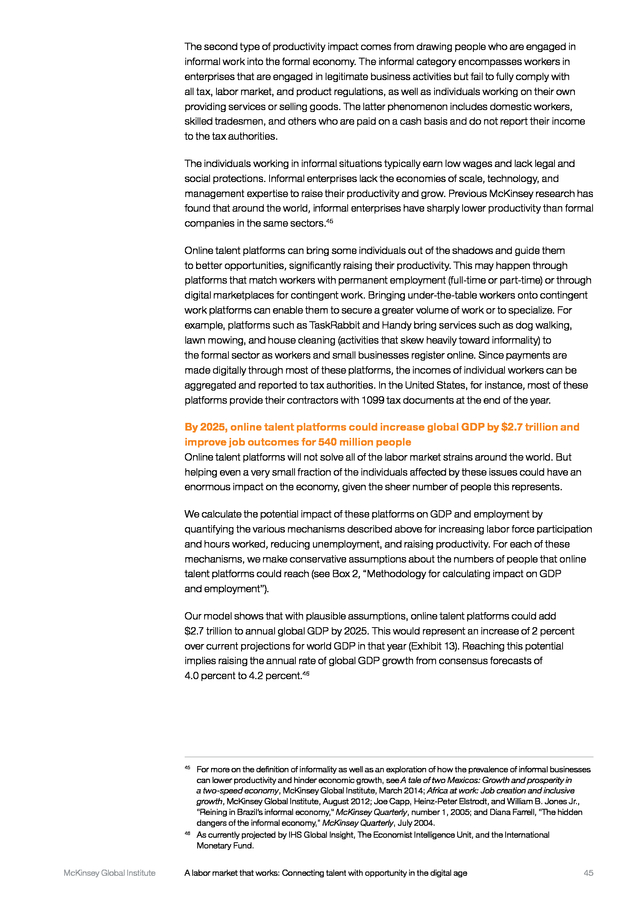

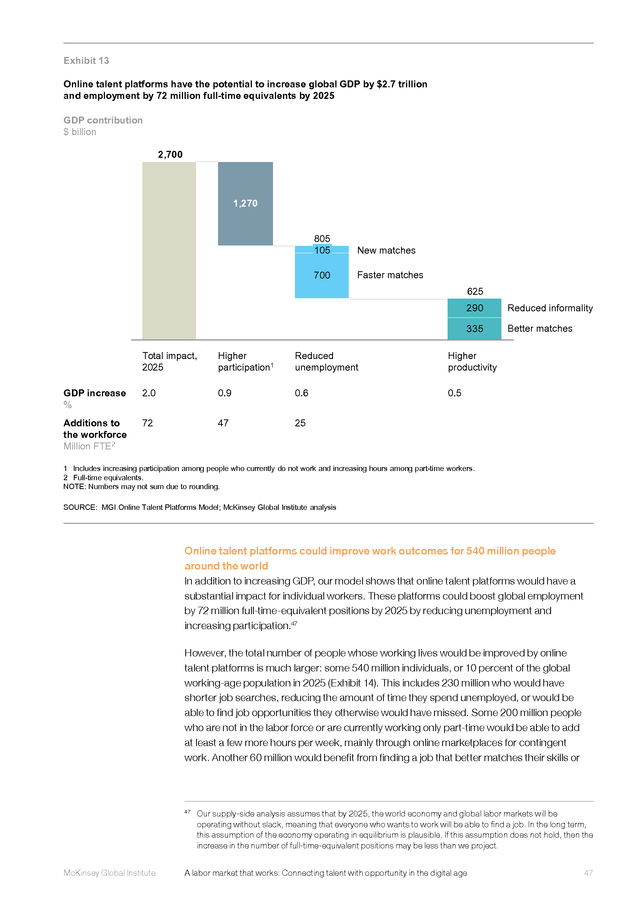

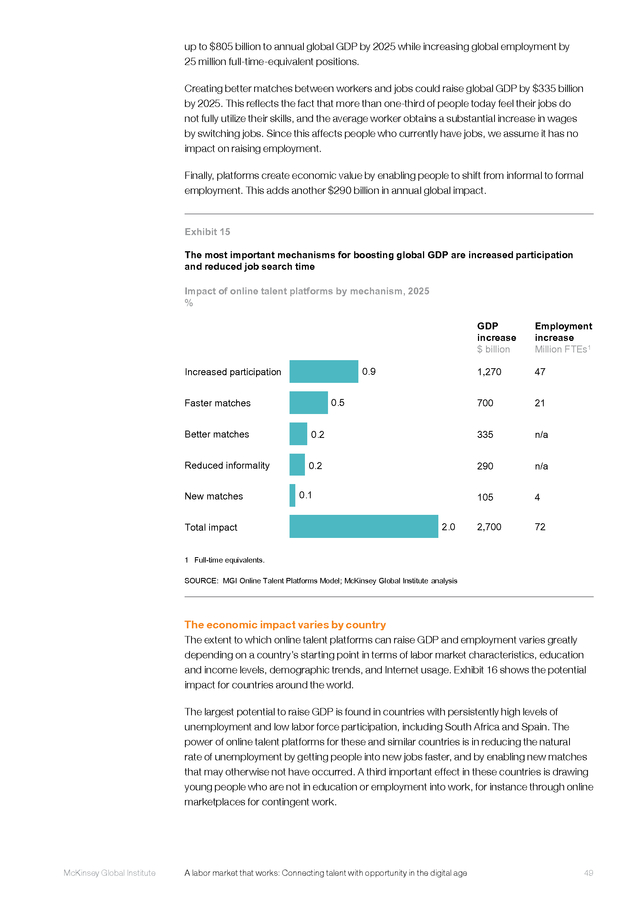

Exhibit E3 Online talent platforms have the potential to increase global GDP by $2.7 trillion and employment by 72 million full-time equivalents by 2025 GDP contribution $ billion 2,700 1,270 805 105 New matches 700 Faster matches 625 290 Reduced informality 335 Better matches Total impact, 2025 Higher participation1 Reduced unemployment Higher productivity GDP increase % 2.0 0.9 0.6 0.5 Additions to the workforce Million FTE2 72 47 25 1 Includes increasing participation among people who currently do not work and increasing hours among part-time workers. 2 Full-time equivalents. NOTE: Numbers may not sum due to rounding. SOURCE: MGI Online Talent Platforms Model; McKinsey Global Institute analysis Because such a large population is currently inactive or underutilized, the largest impact (some $1.3 trillion) comes from increasing labor participation and hours worked. Reducing unemployment by shortening job searches and enabling matches that would otherwise not have happened is the second-largest effect, worth $805 billion. Raising productivity by facilitating better job matches and a shift from informal to formal employment raises global GDP by $625 billion. The impact on GDP and employment varies across countries, depending on their labor market characteristics, demographics, and Internet usage. We created a detailed model for seven of the world’s largest economies and then extrapolated the results globally (Exhibit E4).

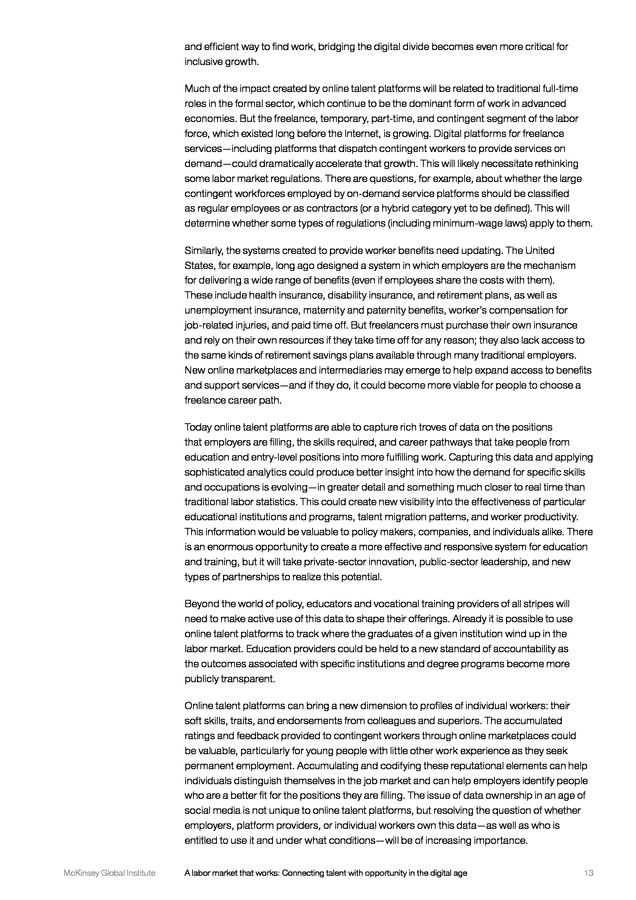

The largest potential to raise GDP is found in countries with persistently high levels of unemployment and low participation, including South Africa, Greece, and Spain. The power of online talent platforms for these and similar countries lies in reducing the duration of unemployment and increasing hours worked.4 For the United States and most of Western Europe, the largest impact comes from enabling more people to work through fractional employment platforms. Most emerging economies can capture significant gains through moving people from informal to formal employment. 4 McKinsey Global Institute One caveat is that this is a supply-side analysis that assumes jobs will be available for people who want them. A labor market that works: Connecting talent with opportunity in the digital age 7 . Exhibit E4 The potential impact of online talent platforms varies across countries GDP Economies Advanced >0.9% 0.5–0.9% <0.4% Employment Share of GDP (%) GDP Increased participation % Faster matches New matches Better matches Reduced informality >3% 2–3% <2% Employment GDP $ % of em- 1,000 billion ployees people Spain 3.3 0.8 1.7 0.4 0.2 0.2 58 4.4 748 Greece 3.2 0.9 1.5 0.4 0.2 0.2 10 4.3 161 Portugal 2.5 0.8 1.0 0.3 0.1 0.2 7 3.2 140 Italy 2.5 1.0 0.9 0.2 0.2 0.2 52 3.1 734 United States1 2.3 1.1 0.6 0.1 0.4 0.1 512 2.7 4,091 France 2.3 1.1 0.7 0.1 0.3 0.1 64 2.9 784 Belgium 2.2 1.1 0.5 0.1 0.3 0.2 12 2.7 120 Sweden 2.1 0.9 0.6 0.1 0.4 0.1 11 2.5 119 Finland 2.1 1.0 0.5 0.1 0.3 0.1 5 2.5 61 Denmark 2.1 0.9 0.5 0.1 0.4 0.1 6 2.4 67 Canada 2.0 1.0 0.5 0.1 0.4 0.1 41 2.4 436 United Kingdom1 2.0 0.9 0.5 0.1 0.4 0.1 68 2.4 766 Australia 1.9 1.0 0.4 0.1 0.4 0.1 28 2.2 271 Germany1 1.7 0.8 0.4 0.1 0.4 0.1 70 1.9 708 Switzerland 1.7 0.9 0.3 0.1 0.4 0.1 8 1.9 98 Singapore 1.7 1.0 0.2 0.0 0.3 0.1 9 1.9 67 South Korea 1.6 0.9 0.2 0.0 0.4 0.1 39 1.8 416 Netherlands 1.6 0.7 0.3 0.0 0.4 0.1 14 1.8 147 Austria 1.5 0.8 0.3 0.0 0.3 0.1 7 1.7 70 Japan1 1.5 0.7 0.2 0.0 0.4 0.1 78 1.6 906 South Africa 3.9 1.1 2.1 0.1 0.2 0.4 20 5.0 861 Colombia 3.1 0.9 1.4 0.2 0.1 0.5 25 3.7 946 Philippines 2.7 0.9 0.9 0.1 0.2 0.6 22 2.9 1,359 Egypt 2.7 1.4 0.5 0.1 0.2 0.4 21 3.2 945 Russia 2.5 0.9 0.7 0.1 0.2 0.6 82 2.5 1,605 Hungary 2.5 1.0 0.8 0.2 0.2 0.4 7 2.9 110 Nigeria 2.5 1.3 0.3 0.1 0.2 0.7 20 2.6 1,889 Turkey 2.5 1.3 0.4 0.1 0.3 0.4 41 2.8 799 Brazil1 2.4 0.8 0.8 0.1 0.1 0.6 69 2.6 2,686 Peru 2.3 0.8 0.5 0.1 0.2 0.8 12 2.0 320 Chile 2.3 0.9 0.8 0.1 0.2 0.3 12 2.8 210 Mexico 2.3 1.0 0.6 0.1 0.1 0.4 60 2.6 1,349 Poland 2.2 0.9 0.6 0.1 0.4 0.2 27 2.5 353 Indonesia 2.2 0.9 0.8 0.1 0.1 0.3 57 2.7 3,538 Kenya 2.2 1.1 0.4 0.1 0.2 0.4 3 2.4 536 Saudi Arabia 2.1 1.3 0.2 0.1 0.3 0.2 32 2.5 276 Czech Republic 1.9 0.8 0.4 0.1 0.4 0.1 7 2.1 103 Emerging Malaysia 1.9 1.1 0.1 0.0 0.2 0.5 16 2.0 286 India1 1.9 1.2 0.2 0.0 0.2 0.3 222 2.2 11,343 Thailand 1.8 0.8 0.1 0.0 0.1 0.8 20 1.3 511 China1 1.5 0.7 0.4 0.0 0.1 0.2 485 1.7 12,868 1 Detailed results and insights are available for these countries. NOTE: Numbers may not sum due to rounding. SOURCE: MGI Online Talent Platforms Model; McKinsey Global Institute analysis 8 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary . Improving work outcomes for some 540 million people Our model shows that online talent platforms could increase global employment by 72 million full-time-equivalent positions (or 2.4 percent) by 2025. The number of individuals who could reduce job search time, add hours, or find better jobs is much larger, however. In total, some 540 million people around the world—roughly 10 percent of the global workingage population—could benefit from online talent platforms by 2025 (Exhibit E5). This number is equivalent to the entire population of the European Union. This includes 230 million who would have shorter job searches, reducing the amount of time they spend unemployed, or who would find job opportunities they otherwise would have missed.

Some 200 million people who are not in the labor force or are currently working part-time could add at least a few more hours per week through contingent work platforms. Another 60 million could find jobs that better match their skills or preferences. And 50 million people in informal employment could find formal-sector jobs that give them better prospects for stability and growth. Exhibit E5 By 2025, online talent platforms could benefit some 540 million people, or 10 percent of the working-age population Million people, 2025 Number of beneficiaries by impact mechanism % of the working-age population1 540 Reduced informality 1 Better matches 60 1 Higher participation 200 4 % of the working-age population1 10 50 Number of beneficiaries by country China 92 India 77 United States 41 21 Brazil 9.1 8.1 18.5 14.2 Japan 230 5 11.2 United Kingdom 7 16.1 Germany Reduced job search time 8 6 12.5 The total number of people who could potentially benefit far exceeds the 72 million full-time equivalent jobs created. The 540 million figure includes people who will experience faster job searches, people who are already employed but find better jobs, people who add hours on freelance platforms, and people who move into the formal sector. 1 Ages 15–64. NOTE: Numbers may not sum due to rounding. SOURCE: MGI Online Talent Platforms Model; McKinsey Global Institute analysis Thus far, most users of the online talent platforms focusing on traditional jobs have been educated and skilled professionals. They have also been the biggest beneficiaries, as many are already receiving job offers through passive recruiting and watching as employers bid up their salaries.

While these platforms are expanding into a broader range of occupations, sectors, and geographies, workers who lack credentials or distinctive skills have not migrated onto these sites to the same degree. But as job searching becomes more digitized McKinsey Global Institute A labor market that works: Connecting talent with opportunity in the digital age 9 . for everyone, less skilled workers may similarly benefit. However, it is also possible that employers will be able to replace them more easily and at lower cost, squeezing their wages. Showcasing new dimensions of profiles of individual workers, such as their soft skills, traits, and endorsements from colleagues and superiors, will be important. This may allow workers without credentials to highlight traits that set them apart, such as work ethic, creativity, and customer service. Reducing public spending on unemployment and making education spending more effective By reducing the number of unemployed people and the length of time spent searching for a job, online talent platforms could reduce the demand for unemployment benefits as well as public-sector job-placement, training, and subsidy programs. They can improve the way these programs function by applying better data, new approaches, and new technologies— as well as reducing the overall need for the government to act as an intermediary between the unemployed and the job market.

They can also improve data sharing and coordination between agencies at various levels of government as well as creating a basis for partnerships involving private-sector employers and education providers. 9% reduction in public spending on labor market programs We estimate that spending on labor market programs could be lowered by as much as 9 percent—or $18 billion annually—as online talent platforms cut the length of time people are out of work in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan alone. These savings could then be reinvested in other productive uses, which would also add to GDP growth over the long term, although we have not calculated this effect. Similarly, considerable public and personal resources go into educating people who end up not working or do not use their training in their jobs. While labor market outcomes are not the sole purpose of higher education, the underemployment and unemployment of people with tertiary degrees suggests considerable misallocation.

In the United States, for example, more than one-quarter of workers holding bachelor’s or advanced degrees earn less than the median annual wage for two-year associate degree holders. Similarly, one-third of those with associate degrees earn less than the median wage for high school graduates. By examining the number of bachelor’s degree-holders who are underemployed today, we estimate that some $89 billion (14 percent) in annual education spending in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, Brazil, India, and China does not lead to successful labor market outcomes. Online talent platforms are becoming repositories of vast data sets that can illuminate trends in the demand for specific skills, and this capability can help young people make more informed decisions about training and career paths. Better information can improve the allocation of funding for education and training that improves career prospects for more individuals, raising their lifetime earning potential. Long-term dynamic benefits Online talent platforms could create important positive dynamics for economies over the long term.

We do not attempt to quantify these, but they could prove to be as significant as any of the measured effects discussed above. They could, for example, make it easier for highly talented individuals to find one another, offering new possibilities for collaboration and innovation. While this possibility cannot be predicted, it is worth remembering that chance encounters in Silicon Valley produced some of the greatest technological innovations of our generation. The impact on individual companies (discussed in greater detail below but excluded from our GDP calculation) could similarly ripple through entire economies. As leading companies adopt online talent platforms, they are likely to attract higher-performing employees and 10 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary .

boost results. As they do, they will win out over less competitive companies, supporting the process of creative destruction that generates long-term improvements in productivity and living standards. Finally, by enabling a more detailed understanding of the demand for particular skills and better educational and training choices, online talent platforms could shift the entire mix of skills over the long term, increasing human capital and economic vitality. The process of reaching equilibrium in supply and demand can take years, however—and in the meantime, the availability of new fractional employment options may help to cushion the effects of this adjustment for some workers. Online talent platforms can revolutionize the way organizations attract, retain, and develop talent In a more digitally connected and knowledge-based economy, companies increasingly create value from ideas, innovation, research, and expertise. Finding the right talent matters and drives results.

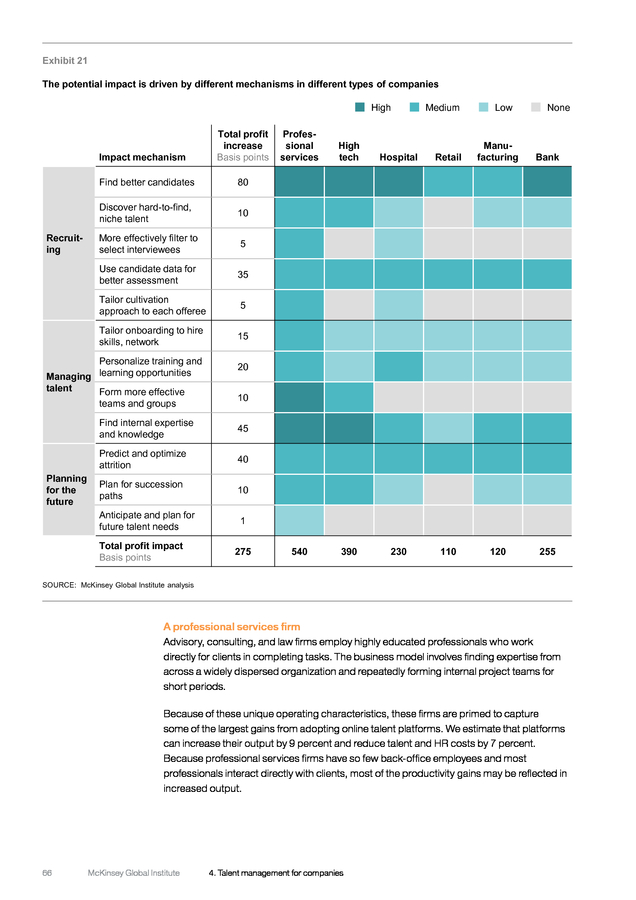

But organizations often struggle to land the right candidates, draw the best performance out of their workforces, and develop the leadership they need to meet their strategic goals. Today leading companies are adopting online talent platforms as they realize that human capital management can produce significant returns on investment. To date, the clearest value of these platforms has been in harnessing the power of search technology for hiring, including new tools for passive recruiting, social recruiting, and applicant screening. But platforms are now available to improve the full spectrum of talent management, from onboarding and compensation to engagement, team formation, and performance feedback. 275BPS average improvement in company profit margins By modeling sample organizations in a range of industries with diverse workforce mixes, operating models, and financial characteristics, we estimate that online talent platforms can increase a company’s output by up to 9 percent and lower costs related to talent and human resources by up to 7 percent (Exhibit E6).5 Companies with a large share of highly skilled workers have significant opportunities to improve recruiting and personalize various aspects of talent management, including training, incentives, and career paths.

Conversely, online talent platforms can also benefit companies with large low-skilled workforces and high attrition rates through better screening and assessment of job candidates. Online talent platforms have the greatest potential for high-tech and professional services firms, both of which depend on specialized, expensive, and hard-to-find talent. These firms can also benefit from applying online talent platforms internally to make it easier for their employees to find expertise across geographically dispersed organizations and to form more compatible and productive teams. Hospitals stand to gain from the ability to attract better talent and hard-to-find specialists and from staffing more compatible teams of nurses and doctors.

Retailers and banks would benefit mainly from better screening and assessment of candidates to find those who will provide better customer service and are less likely to quit what have traditionally been high-churn positions. Online talent platforms could provide large benefits to small businesses that lack dedicated HR departments. Organizations face substantial challenges in making the shift to online talent platforms, however. Many still lack integrated systems for managing their current workforces, let alone for identifying potential recruits or engaging in long-term planning.

The companies at the leading edge of these trends are cultivating real analytic and social media skills in their HR We model results for six representative companies: a professional services firm, a high-tech firm, a hospital, a retail chain, a manufacturer, and a retail bank. 5 McKinsey Global Institute A labor market that works: Connecting talent with opportunity in the digital age 11 . departments. They are also creating more personalized work environments with interactive tools embedded into everyday processes to support business priorities. Exhibit E6 Online talent platforms can increase output by up to 9 percent and reduce costs by up to 7 percent Incremental impact of online talent platforms Model company Revenues $ billion Employees Cost reduction2 % Output increase1 % Professional services 2.5 5,000 Technology 11.1 10,000 Hospital 0.5 2,000 Retail 2.8 15,000 3 Manufacturing 2.4 10,000 3 31.7 100,000 Bank 9 7 7 540 4 390 4 230 6 5 110 4 120 2 6 5 Profit impact Basis points 5 255 275 1 Includes productivity gains in front- and middle-office workers, which can translate into revenue or other increased output opportunities. 2 Includes productivity effect in middle- and back-office workers, and savings in recruiting, interviewing time, training, onboarding, and attrition costs. Note: Numbers may not sum due to rounding. SOURCE: BLS; company annual reports; McKinsey Global Institute analysis Companies will need to prepare for a whole new phase in the war for talent now that workers have publicly visible profiles. Competitors can more easily lure away valued employees (and even entire teams). The labor market fluidity enabled by online talent platforms is a positive dynamic for individuals and the broader economy, but companies may face increased costs due to higher turnover.

This makes it more important than ever for companies to create a compelling value proposition for their workforce. Those that do are likely to be net beneficiaries of the digitization of talent markets. Just as they carefully manage their consumer brands, companies now have to be conscious of managing their reputations as employers. Online talent platforms pose new questions, opportunities, and challenges for the long term Policy makers should have significant incentives to enable the growth of online talent platforms, given their potential to increase economic dynamism, raise employment, and improve public spending on unemployment programs and education.

To capture these benefits, they will need to address a number of complex issues. The first is ensuring that all citizens have affordable broadband access. As of mid-2014, less than half of China’s population and less than 20 percent of India’s population were online, for example. In the United States, which has one of the highest Internet penetration rates in the world, some 50 million people remain offline.

As talent platforms become the most accepted 12 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary . and efficient way to find work, bridging the digital divide becomes even more critical for inclusive growth. Much of the impact created by online talent platforms will be related to traditional full-time roles in the formal sector, which continue to be the dominant form of work in advanced economies. But the freelance, temporary, part-time, and contingent segment of the labor force, which existed long before the Internet, is growing. Digital platforms for freelance services—including platforms that dispatch contingent workers to provide services on demand—could dramatically accelerate that growth. This will likely necessitate rethinking some labor market regulations.

There are questions, for example, about whether the large contingent workforces employed by on-demand service platforms should be classified as regular employees or as contractors (or a hybrid category yet to be defined). This will determine whether some types of regulations (including minimum-wage laws) apply to them. Similarly, the systems created to provide worker benefits need updating. The United States, for example, long ago designed a system in which employers are the mechanism for delivering a wide range of benefits (even if employees share the costs with them). These include health insurance, disability insurance, and retirement plans, as well as unemployment insurance, maternity and paternity benefits, worker’s compensation for job-related injuries, and paid time off.

But freelancers must purchase their own insurance and rely on their own resources if they take time off for any reason; they also lack access to the same kinds of retirement savings plans available through many traditional employers. New online marketplaces and intermediaries may emerge to help expand access to benefits and support services—and if they do, it could become more viable for people to choose a freelance career path. Today online talent platforms are able to capture rich troves of data on the positions that employers are filling, the skills required, and career pathways that take people from education and entry-level positions into more fulfilling work. Capturing this data and applying sophisticated analytics could produce better insight into how the demand for specific skills and occupations is evolving—in greater detail and something much closer to real time than traditional labor statistics. This could create new visibility into the effectiveness of particular educational institutions and programs, talent migration patterns, and worker productivity. This information would be valuable to policy makers, companies, and individuals alike.

There is an enormous opportunity to create a more effective and responsive system for education and training, but it will take private-sector innovation, public-sector leadership, and new types of partnerships to realize this potential. Beyond the world of policy, educators and vocational training providers of all stripes will need to make active use of this data to shape their offerings. Already it is possible to use online talent platforms to track where the graduates of a given institution wind up in the labor market. Education providers could be held to a new standard of accountability as the outcomes associated with specific institutions and degree programs become more publicly transparent. Online talent platforms can bring a new dimension to profiles of individual workers: their soft skills, traits, and endorsements from colleagues and superiors.

The accumulated ratings and feedback provided to contingent workers through online marketplaces could be valuable, particularly for young people with little other work experience as they seek permanent employment. Accumulating and codifying these reputational elements can help individuals distinguish themselves in the job market and can help employers identify people who are a better fit for the positions they are filling. The issue of data ownership in an age of social media is not unique to online talent platforms, but resolving the question of whether employers, platform providers, or individual workers own this data—as well as who is entitled to use it and under what conditions—will be of increasing importance. McKinsey Global Institute A labor market that works: Connecting talent with opportunity in the digital age 13 .

For an ever-broader segment of the workforce, from students to retirees, individuals will have an opportunity to take more active control of their careers. This starts with building a personal online presence and network. As data collection and analysis become more sophisticated, users will have to be mindful that every online interaction can affect their professional reputation. Talent platforms can offer users a great deal of insight, but it is up to individuals to act on that information and use it to plot their long-term career paths. They will have greater agency, and in the future, they may feel less trapped in stagnant local economies as they can more easily learn about openings in other locations and options for long-distance collaboration. ••• The strains in labor markets did not develop overnight, and they arose from multifaceted causes.

In an age of automation, technology is often blamed for these issues. But it could prove to be part of the solution, too. Online platforms are already fundamentally altering the way individuals go about searching for work and the way employers approach hiring and talent development.

While most early adopters have been professionals, these platforms are beginning to draw in a wider range of talent and spreading to new industries and geographies. These are early days in their evolution, but as these platforms rapidly expand, the cumulative benefits are growing. Capturing their full potential will require a thoughtful policy framework, private-sector investment and innovation, and—perhaps most important—a whole new level of adaptability on the part of individual workers. 14 McKinsey Global Institute Executive summary .

© Getty Images . © Getty Images . 1. THE DISCONNECT BETWEEN WORKERS AND WORK College graduates in nearly any advanced economy in the 1970s could choose to travel a predictable career path: spot an ad for an entry-level job in the local newspaper, enter a company’s training program, move on to better-paying positions at regular intervals, and retire to enjoy a comfortable lifestyle decades later. Previous recessions brought spikes in unemployment, but layoffs tended to be cyclical; workers were called back or found new positions without being thrown out of work for extended periods. Over the last 20 years, those dynamics have changed. New technologies, the falling costs of communication and transportation, and the opening of markets around the world enabled companies to create a global footprint.

Layoffs in advanced economies went from cyclical to permanent, forcing midcareer workers to scramble to find new lines of work. “Jobless recoveries” became the norm, at least in the United States and many countries across Europe.6 850M individuals in seven major economies who are unemployed, inactive, or part-time Today workers around the world face a much more daunting job market. The worst global recession since the Great Depression still casts a long shadow, but deeper structural changes have been building for decades.

Youth unemployment is soaring in countries across Southern and Central Europe; in Spain, for example, more than half of young people lack jobs, and even college graduates struggle to find work. In the United States, students are entering the job market with a mountain of debt, but some find that employers place little value on their degrees. Many of China’s new university graduates are not landing the highpaying white-collar jobs they expected.

Around the world, millions of young people are stuck in low-skill jobs that leave them frustrated and feeling that they could be accomplishing so much more. This is only one snapshot of labor market dysfunction from a much larger picture that spans countries and demographic groups. Companies and industries are being rapidly transformed by the powerful currents of globalization and technology, and the skills they need are changing. But even as the business environment has grown more dynamic and fast-paced over the past two decades, the process of educating and training individuals and then connecting them with the world of work has not evolved to the same degree.

The ability of labor markets to match willing workers with rewarding job opportunities has been breaking down for many years in advanced economies, and new mechanisms are not taking root quickly enough as workforce needs grow more complex in emerging economies. This disconnect is a market failure that touches millions of lives. Looking at just seven of the world’s major economies (the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, China, India, and Brazil), we find that some 120 million people are unemployed or working part-time involuntarily, and 730 million people of working age are not participating in the labor force. A recent survey conducted by LinkedIn found that even 37 percent of those who do have jobs report feeling overqualified for their current roles. 6 For more discussion of these trends, see Global employment trends 2012: Risk of a jobless recovery? International Labour Organization, 2014; The world at work: Jobs, pay, and skills for 3.5 billion people, McKinsey Global Institute, June 2012; and An economy that works: Job creation and America’s future, McKinsey Global Institute, June 2011. .

For individuals, the real-world consequences of this disconnect can include economic insecurity and poverty, deteriorating health, and a lack of fulfillment and pride in what they do every day. On the other side of the equation, companies say they often cannot fill open positions that require specific skills. They may wind up hiring employees who are not the right fit—and are less productive, less innovative, and plagued by morale issues as a result. In some industries, the inability to find the right talent is a constraint on growth. When these stories multiply, they erode productivity across the broader economy, deepen inequality, and fray the social fabric. 36% of global employers say they cannot find the talent they need Labor markets are ripe for positive disruption.

Because of their unique ability to create transparency, aggregate data, and enable sophisticated searches, online talent platforms can advance that disruption. They are not a panacea by any means; this research assumes that they can address only a fraction of the biggest problems in today’s labor markets. But we project that they can change the outcome for 10 percent of the working-age population by reducing the time workers spend unemployed, connecting them with more fulfilling jobs, or helping them increase their income through flexible part-time arrangements—and that translates into new opportunities for some 540 million individuals. Labor markets around the world suffer from problems that lead to unrealized economic and individual potential Frictions and imbalances are apparent in labor markets around the world, albeit to varying degrees in different countries and sectors.

The Great Recession clearly worsened these strains, but they are not simply a product of the business cycle. In many countries, labor markets have been deteriorating for decades. All of these issues increase the hurdles for individual workers seeking fulfilling, productive work and waste human potential.

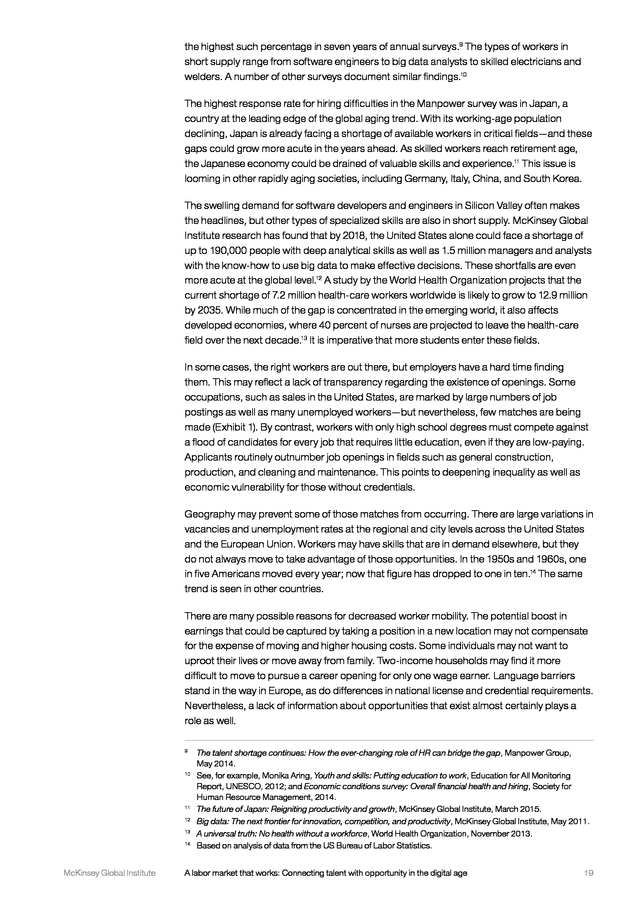

In most countries, these strains appear to be growing worse. Here we focus on four key issues that online talent platforms can partially address. Problems matching jobs and workers Many companies and workers seem to have trouble finding one another. The skills that many workers have may not match the vacancies at hand; information gaps may prevent qualified job seekers from ever learning about promising openings; and the right workers may be in the wrong geographies.

The Beveridge curve depicts the steady-state relationship between the unemployment rate and the vacancy rate over the course of a business cycle. It was relatively stable in the United States before the Great Recession, but the curve has shifted since 2009, with more vacancies for a given level of unemployment. This could reflect a decline in matching efficiency (although it could also simply reflect the impact of the recession). This trend has also been observed in other OECD countries, including the United Kingdom, Portugal, and Spain.7 Economists have been debating the existence of a broad-based “skills gap,” at least in the aggregate, given that wages have not been rising.8 But executives consistently report hiring difficulties for specific positions at their own firms and in particular industries and regions, indicating issues at the micro level.

Thirty-six percent of the 37,000 global employers surveyed by Manpower stated that they could not find the talent they needed in 2014— Bart Hobijn and AyÅŸegül Åžahin, Beveridge curve shifts across countries since the Great Recession, paper presented at the 13th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference of the International Monetary Fund, November 8–9, 2012. See also Peter Diamond and AyÅŸegül Åžahin, Shifts in the Beveridge curve, September 2014; and Sylvain Leduc and Zheng Liu, “Uncertainty and the slow labor market recovery,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter, July 2013. 8 For more on the debate over the skills gap, see Paul Krugman, “Jobs and skills and zombies,” The New York Times, March 30, 2014; Paul Osterman and Andrew Weaver, Why claims of skills shortages in manufacturing are overblown, Economic Policy Institute, March 2014; and James Bessen, “Employers aren’t just whining: The ‘skills gap’ is real,” Harvard Business Review, August 25, 2014. 7 18 McKinsey Global Institute 1. The disconnect between workers and work .

the highest such percentage in seven years of annual surveys.9 The types of workers in short supply range from software engineers to big data analysts to skilled electricians and welders. A number of other surveys document similar findings.10 The highest response rate for hiring difficulties in the Manpower survey was in Japan, a country at the leading edge of the global aging trend. With its working-age population declining, Japan is already facing a shortage of available workers in critical fields—and these gaps could grow more acute in the years ahead. As skilled workers reach retirement age, the Japanese economy could be drained of valuable skills and experience.11 This issue is looming in other rapidly aging societies, including Germany, Italy, China, and South Korea. The swelling demand for software developers and engineers in Silicon Valley often makes the headlines, but other types of specialized skills are also in short supply.

McKinsey Global Institute research has found that by 2018, the United States alone could face a shortage of up to 190,000 people with deep analytical skills as well as 1.5 million managers and analysts with the know-how to use big data to make effective decisions. These shortfalls are even more acute at the global level.12 A study by the World Health Organization projects that the current shortage of 7.2 million health-care workers worldwide is likely to grow to 12.9 million by 2035. While much of the gap is concentrated in the emerging world, it also affects developed economies, where 40 percent of nurses are projected to leave the health-care field over the next decade.13 It is imperative that more students enter these fields. In some cases, the right workers are out there, but employers have a hard time finding them.

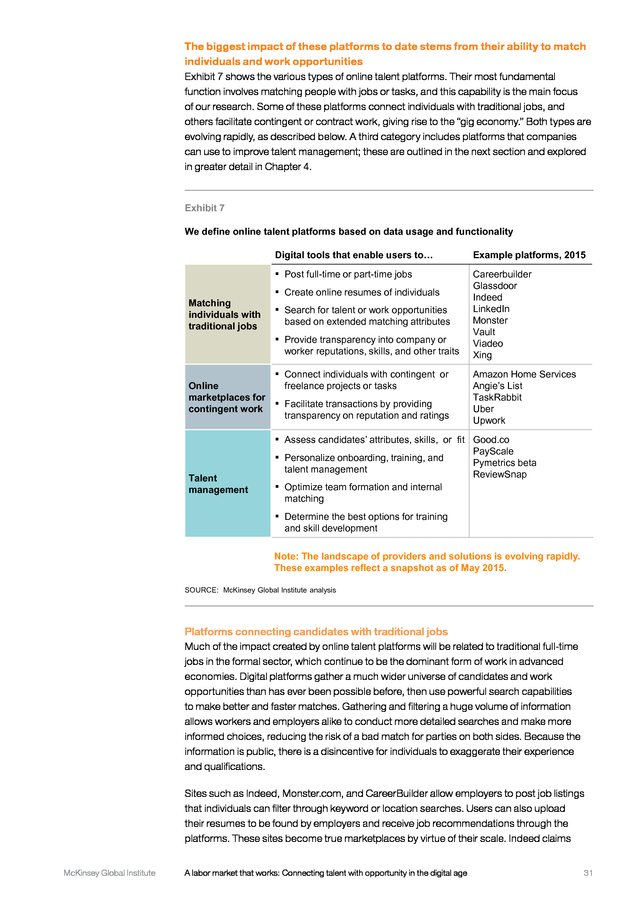

This may reflect a lack of transparency regarding the existence of openings. Some occupations, such as sales in the United States, are marked by large numbers of job postings as well as many unemployed workers—but nevertheless, few matches are being made (Exhibit 1). By contrast, workers with only high school degrees must compete against a flood of candidates for every job that requires little education, even if they are low-paying. Applicants routinely outnumber job openings in fields such as general construction, production, and cleaning and maintenance.

This points to deepening inequality as well as economic vulnerability for those without credentials. Geography may prevent some of those matches from occurring. There are large variations in vacancies and unemployment rates at the regional and city levels across the United States and the European Union. Workers may have skills that are in demand elsewhere, but they do not always move to take advantage of those opportunities.

In the 1950s and 1960s, one in five Americans moved every year; now that figure has dropped to one in ten.14 The same trend is seen in other countries. There are many possible reasons for decreased worker mobility. The potential boost in earnings that could be captured by taking a position in a new location may not compensate for the expense of moving and higher housing costs. Some individuals may not want to uproot their lives or move away from family.

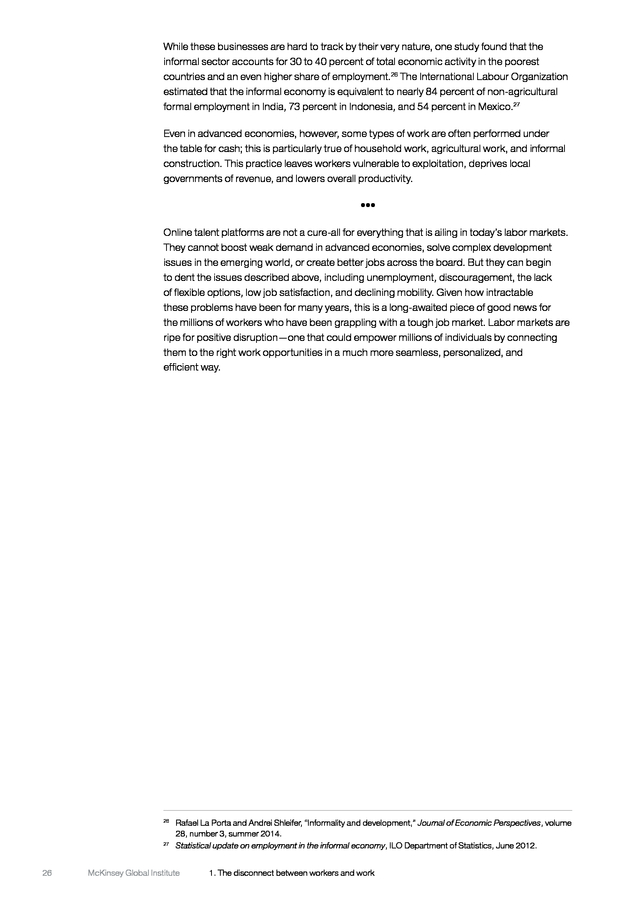

Two-income households may find it more difficult to move to pursue a career opening for only one wage earner. Language barriers stand in the way in Europe, as do differences in national license and credential requirements. Nevertheless, a lack of information about opportunities that exist almost certainly plays a role as well. The talent shortage continues: How the ever-changing role of HR can bridge the gap, Manpower Group, May 2014. 10 See, for example, Monika Aring, Youth and skills: Putting education to work, Education for All Monitoring Report, UNESCO, 2012; and Economic conditions survey: Overall financial health and hiring, Society for Human Resource Management, 2014. 11 The future of Japan: Reigniting productivity and growth, McKinsey Global Institute, March 2015. 12 Big data: The next frontier for innovation, competition, and productivity, McKinsey Global Institute, May 2011. 13 A universal truth: No health without a workforce, World Health Organization, November 2013. 14 Based on analysis of data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. 9 McKinsey Global Institute A labor market that works: Connecting talent with opportunity in the digital age 19 . Exhibit 1 Inefficient labor matching in the United States is evident from large numbers of both unemployed people and vacant positions in certain fields Ratio of number of unemployed people to job postings, 2014 More job postings Computer and mathematical 0.2 Health-care practitioners 0.5 Architecture and engineering 0.8 Natural and social science 1.0 Social services 1.5 Maintenance and repair 1.7 Arts, design, and entertainment 1.8 Food services Production Cleaning and maintenance More unemployment Construction and extraction 4.2 5.5 10.7 18.7 SOURCE: Burning Glass; BLS; McKinsey Global Institute analysis Poor utilization of human capital In all countries, large segments of the working-age population do not work. This manifests as high levels of unemployment, low labor force participation, and underemployment of part-time workers who wish to work full-time.15 In the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, Brazil, China, and India, we find 75 million people formally unemployed. But this number is only part of the story. In most countries, 30 to 45 percent of the workingage population is underutilized—that is, unemployed, inactive in the workforce, or working part-time. Across these seven economies alone, this translates into some 850 million people (Exhibit 2).

While some of them have no doubt opted out of the workforce or chosen parttime employment as a matter of personal preference, this number still represents millions of individuals who could raise their incomes while engaging in more productive, fulfilling work. 15 20 “Underemployment” is defined as the share of the workforce consisting of highly skilled workers in low-skill or low-paying jobs plus those in part-time roles who would like full-time employment. McKinsey Global Institute 1. The disconnect between workers and work . Exhibit 2 850 million people across seven countries are economically underutilized, accounting for 30 to 50 percent of the working-age population %; million people Working-age population (age 15–64) by status and country, 2013 834 100% = 1,010 202 139 78 54 41 28 25 25 23 24 5 3 4 5 13 13 60 59 23 Inactive 44 Unemployed1 4 4 6 Part-time2 Full-time 2 74 India Total number of 381 underutilized workers4 Million 70 62 54 Size of the inactive population by group, 2015 20 52 China United States Brazil Japan3 Germany United Kingdom 273 77 41 37 21 17 ~850 100% = 13 49 India 11 10 6 11 364 Women5 Men5 16 33 China 10 10 1 30 230 Inactive youth Students United States 11 22 6 21 39 1 57 Discouraged Retired Japan Germany United Kingdom 9 35 Brazil 6 1 23 16 19 6 2 7 16 15 24 35 0 20 52 1 22 1 53 1 24 5 17 12 47 10 1 Unemployed as defined here does not equal the unemployment rate because it is divided by the total population instead of the labor force. 2 Part-time employment data are not available for China, Brazil, and India. 3 For Japan we use non-regular employment provided by the “Employment status survey of Japan” as a proxy for part-time employment. 4 Inactive, unemployed, and part-time. 5 Excluding inactive youth, students, discouraged workers, and retired. NOTE: Numbers may not sum due to rounding. SOURCE: OECD; UN; World Bank; ILO; Eurostat; national sources; McKinsey Global Institute analysis McKinsey Global Institute A labor market that works: Connecting talent with opportunity in the digital age 21 . 3.7 percentage point decline in US labor force participation rate since 2007 The United States has experienced a notable decline in labor force participation since the mid-1990s—and that long-term trend was exacerbated by the Great Recession. The labor force participation rate has fallen by 3.7 percentage points since 2007. Some of this is due to aging. Research has attributed 1.7 percentage points of this decline to aging and another 0.5 percentage points to the cyclical downturn.

The residual component reflects other structural issues.16 Millions of individuals have dropped out of the labor force without a clear reason. Reengaging these people is essential for making their families more economically secure as well as boosting national prosperity. Some of the unemployed and underemployed would like to work full-time. Others may have dropped out of the labor force because the opportunities available were not attractive or because their personal or family needs would not allow a full-time or even a regular part-time schedule.

Some of those in the latter category might choose to work if more flexible and selfdirected work options were available. The long-term unemployed face especially uncertain odds of reentering the workforce. The longer they are out of work, the more discrimination they face from potential employers and the more difficult it is for them to keep their skills up to date. Tens of millions have been unemployed for a year or longer in the seven economies analyzed here. Many eventually become discouraged and drop out of the active job market altogether, so regular unemployment statistics do not even capture their growing ranks.

A wide body of academic research has found correlations between extended unemployment and declines in physical and mental health; studies have even shown poorer academic outcomes among the children of the long-term unemployed.17 Part of the reason for low overall labor force participation is that many women do not work outside the home while they are raising children. There is a gap in labor force participation in nearly all countries (Exhibit 3). Among high-income countries, Lithuania, Finland, Iceland, and Norway have some of the smallest differentials in the world.18 But the gap is particularly pronounced in countries such as India and Brazil.

The numbers are also deceptive in Japan and Germany, where many women work but have part-time jobs. 300M youth around the world not engaged in education, employment or training Youth unemployment has become acute over the past decade. Today some 300 million young people worldwide between the ages of 16 and 24 are not involved in education, employment, or training.19 Of these, approximately 75 million are unemployed, which means they are seeking work but cannot find it; this applies to approximately one in four young people in the European Union.20 The youth unemployment rate is nearly 14 percent worldwide, but it‑ has soared above 50 percent in countries such as Greece, Spain, and South Africa. Without a solid start to propel their careers forward, their economic prospects will be lower over their entire lifetimes.

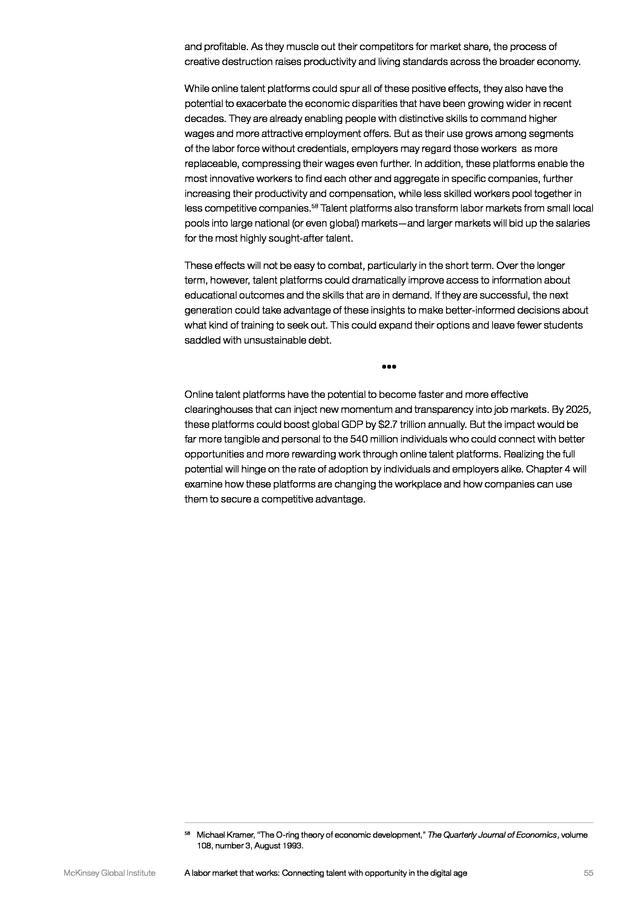

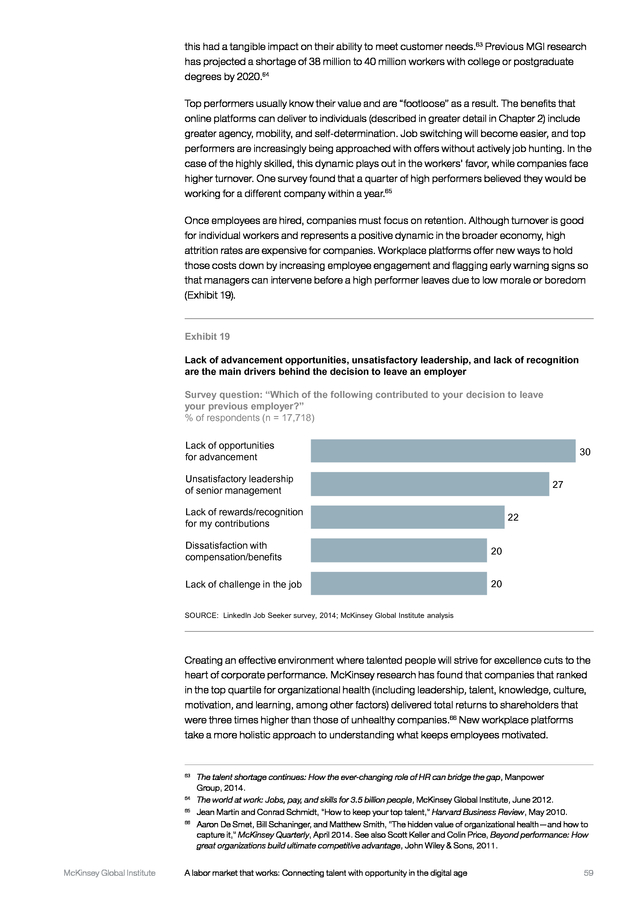

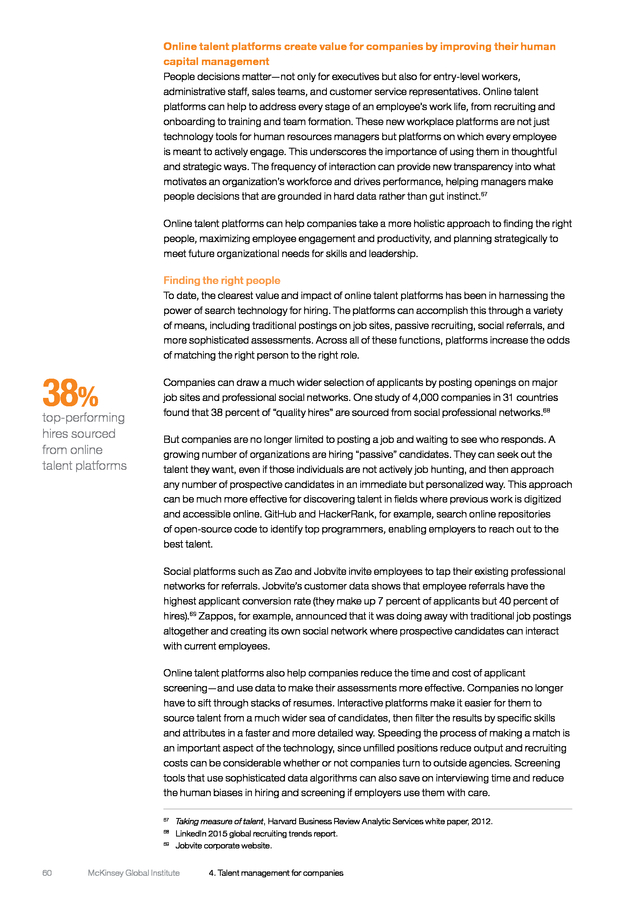

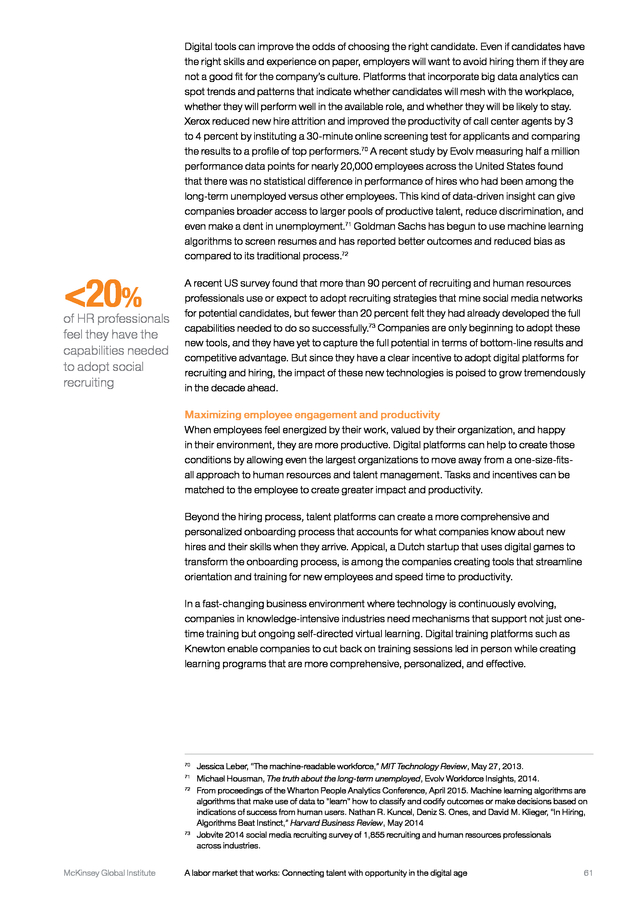

One US study found that the one million young Americans who experienced long-term unemployment during the Great Recession will lose more than $20 billion in earnings over the next decade.21 This trend could even have farreaching consequences for political and social stability. Finally, even people who have jobs may not be fully utilizing their skills. Many workers report feeling overqualified for their current roles, revealing the lack of a good fit between their abilities and their job responsibilities. Thirty-seven percent of global respondents to a recent survey of job seekers conducted by LinkedIn said that they would consider a new job that Economic Report of the President, 2015. Many of these studies are summarized in Austin Nichols, Josh Mitchell, and Stephan Lindner, Consequences of long-term unemployment, Urban Institute, 2013. 18 The global gender gap report 2013, World Economic Forum. 19 Based on World Bank and OECD estimates. 20 Youth unemployment numbers from the International Labor Organization and Eurostat. 21 Sarah Ayres, The high cost of youth unemployment, Center for American Progress, April 2013. 16 17 22 McKinsey Global Institute 1.