Description

A WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY

FOR EUROPE

JUNE 2015

DETAILED ANALYSIS

. In the 25 years since its founding, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) has

sought to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy.

As the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, MGI

aims to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the

facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions.

MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management,

employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business

leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic

industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces

affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have

covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses

on six themes: productivity and growth, natural resources, labour markets,

the evolution of global financial markets, the economic impact of technology

and innovation, and urbanisation.

Recent reports have assessed global flows; the economies of Brazil, Mexico, Nigeria, and Japan; China’s digital transformation; India’s path from poverty to empowerment; affordable housing; the economics of tackling obesity; and prospects for global GDP growth over the next 50 years. MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company directors: Richard Dobbs, James Manyika, and Jonathan Woetzel. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, and Jaana Remes serve as MGI partners. Project teams are led by the MGI partners and a group of senior fellows, and include consultants from McKinsey & Company’s offices around the world.

These teams draw on McKinsey & Company’s global network of partners and industry and management experts. In addition, leading economists, including Nobel laureates, act as research advisers. The partners of McKinsey & Company fund MGI’s research; it is not commissioned by any business, government, or other institution. For further information about MGI and to download reports, please visit www.mckinsey.com/mgi. McKinsey in Europe McKinsey & Company is a global management consulting firm, deeply committed to helping institutions achieve lasting success. McKinsey opened its first offices in Europe in 1959 as the region’s economy began to recover from World War II.

The Firm played an active role in that economic rebirth, working with leading business organisations, as well as governments, nonprofits, and cultural institutions. With offices in 37 cities across Europe, today we serve clients across a wide range of industries and business areas, as well as in the social and public sectors. Copyright © McKinsey & Company 2015 . A WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY FOR EUROPE JUNE 2015 Eric Labaye | Paris Sven Smit | Amsterdam Eckart Windhagen | Frankfurt Richard Dobbs | London Jan Mischke | Zurich Matt Stone | London . PREFACE Seven years on from the global recession, the European economic recovery remains sluggish, and talk persists of countries exiting the Eurozone. Yet Europe has fundamental strengths on which to build. The question is how to use those strengths as a platform for a return to robust growth. In this report, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), which has studied productivity and growth in 30 industries in more than 20 countries over the past 25 years, has examined European growth from three angles. First, the research looked at the supply side and productivity of the European economy, discussing 11 competitiveness growth drivers that together would constitute a sweeping programme of structural reform.

Second, MGI has drawn on previous analysis on debt and deleveraging to examine the current shortage of aggregate demand in Europe and to highlight various options for stimulating investment and job creation. Third, MGI conducted a survey and conjoint analysis of 16,000 Europeans in eight countries during August 2014 to ascertain their aspirations and priorities. This research was led by Eric Labaye, a director of McKinsey and chairman of MGI based in Paris; Sven Smit, a McKinsey director based in Amsterdam; Eckart Windhagen, a McKinsey director based in Frankfurt; Richard Dobbs, a director of McKinsey and MGI based in London; and Jan Mischke, an MGI senior fellow based in Zurich. Matt Stone led the project team.

The team comprised Paraic Behan, Josef Ekman, Asher Ellerman, Sebastian Farquhar, Alec Guzov, Jakob Hensing, Anna Orthofer, Juliane Parys, Björn Saß, Anne-Marie Schoonbeek, Nigel Smith, Charlotte van Dixhoorn, and Ollie Wilson. We would like to acknowledge the helpful support and input of MGI colleagues Jonathan Ablett, Timothy Beacom, Ivo Eman, Lucia Fiorito, Jan Grabowiecki, Karen Jones, Priyanka Kamra, Krzysztof Kwiatkowski, Arshiya Nagi, Aditi Ramdorai, Vivien Singer, and Amber Yang. We are grateful to the academic advisers who helped shape this research and provided challenge and insights and guidance: Martin N. Baily, Bernard L. Schwartz Chair in Economic Policy Development and senior fellow and director of the Business and Public Policy Initiative at the Brookings Institution; Richard N. Cooper, Maurits C.

Boas Professor of International Economics at Harvard University; Howard Davies, chairman of Phoenix Group; Hans-Helmut Kotz, visiting professor of economics at Harvard University and senior fellow at the Center for Financial Studies; and Lord Adair Turner, senior fellow at the Institute for New Economic Thinking. In addition to MGI’s advisers, we benefitted hugely from insights and feedback provided by Bruno Bezard, general director, French Treasury; Laurence Boone, special advisor for International, European Economic and Financial affairs, French Presidency; Michael Bosnjak of the GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, associate professor at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano; Horace “Woody” Brock, president of Strategic Economic Decisions; Marco Buti, director-general for economic and financial affairs at the European Commission; Raffaele della Croce, lead manager, Long-Term Investment Project, at the OECD; Ian Davis, chairman of Rolls-Royce Group PLC; Klaus Günter Deutsch, head of the department of research, industrial and economic policy, Bundesverband Deutscher Industrie e.V.; José Manuel González-Páramo, member of the Board of Directors, BBVA; Yoram Gutgeld, member of the chamber of deputies and economic advisor to the prime minister, Italy; Thomas Heilmann, Senator for Justice and Consumer Protection, Berlin; Kalin Anev Janse, secretary general of the European Stability Mechanism; Ton Kuijlen, emeritus professor of methodology at Tilburg University; Pascal Lamy, president emeritus of the Jacques Delors Institute and former director general of the World Trade . Organisation; Jean Hervé Lorenzi, founder and chairman of the Cercle des économistes; Catherine L. Mann, OECD chief economist and head of the economics department; Giles Merritt, founder and secretary-general of Friends of Europe; Rudolf Minsch, chief economist of Economiesuisse; Peter Mooslechner, executive director, Oesterreichische Nationalbank; Ewald Nowotny, governor, Oesterreichische Nationalbank; Jean PisanyFerry, commissioner general for Policy Planning, Office of the French Prime Minister; Baudouin Regout, policy officer, secretariat general, European Commission; André Sapir, senior fellow at Bruegel; Gerhard Schwarz, director of Avenir Suisse; Jean Tirole, chairman of the Toulouse School of Economics and a Nobel laureate in economics; Claire Waysand, chief of staff for the Minister of Finance and Budget, France; Axel Weber, chairman, UBS; and Thomas Wieser, chair of the Eurogroup Working Group of the European Council. We also had the great honour of testing and refining our thinking in further confidential discussions with many policy makers and officials affiliated with governments and central banks throughout Europe and with European institutions. We thank them all deeply for their time. We would like to thank many McKinsey colleagues for their input and industry expertise, including Konrad Bauer, Cornelius Baur, Alejandro Beltran de Miguel, Kalle Bengtsson, Kirsten Best-Werbunat, Beril Beten, Marco Bianchini, Daniel Boniecki, Bogdan Buleandra, Christian Casal, Adam Chrzanowski, Miklos Dietz, Catarina Eklöf-Sohlström, Nicklas Garemo, Anna Granskog, Philipp Härle, Antony Hawkins, Matthias Heuser, Vivian Hunt, Alain Imbert, Andrew Jordan, Stijn Kooij, Peter Lambert, Sebastien Leger, Frank Mattern, Jean-Christophe Mieszala, Jorge Omeñaca, Jakob Österberg, Occo Roelofsen, Matt Rogers, Jimmy Sarakatsannis, Luuk Speksnijder, Leonardo Totaro, Thomas Vahlenkamp, Cornelius Walter, Peter de Wit, and Louise Young. MGI’s operations team provided crucial support for this research. We would like to thank MGI senior editor Janet Bush; Matt Cooke, Rebeca Robboy, Vanessa Gotthainer, Rachel Grant, Damaris O’Hanlon, and Vanessa Ratcliffe in external communications and media relations; Julie Philpot, editorial production manager; Marisa Carder, graphics specialist; and Deadra Henderson, manager of personnel and administration. We are grateful for all of the input we have received, but the final report is ours and any errors are our own. This report contributes to MGI’s mission to help business and policy leaders understand the forces transforming the global economy, identify strategic locations, and prepare for the next wave of long-term growth.

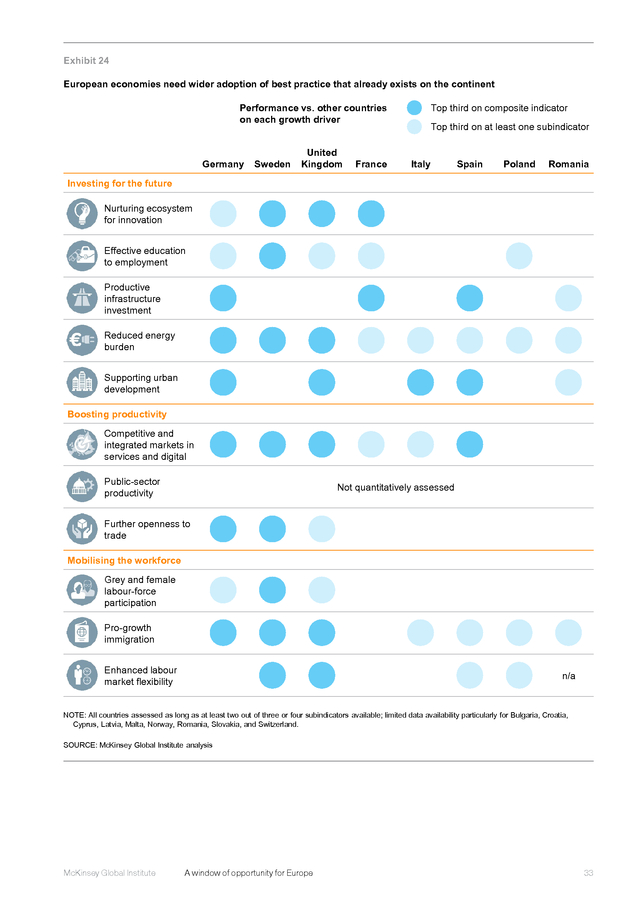

As with all MGI research, this work is independent and has not been commissioned or sponsored in any way by any business, government, or other institution, although it has benefitted from the input and collaborations that we have mentioned. We welcome your emailed comments on the research at MGI@mckinsey.com. Richard Dobbs Director, McKinsey Global Institute London James Manyika Director, McKinsey Global Institute San Francisco Jonathan Woetzel Director, McKinsey Global Institute Shanghai June 2015 . Chapter photo Contents: Construction sky © Getty Images . CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS In brief 1 1. Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal Page 1 Europe’s recent performance has been lacklustre Page 6 But Europe has a foundation of strength and a window of opportunity for renewal Page 10 Europeans in eight countries say they would make tough trade-offs to achieve their high aspirations Page 18 Platform for renewal 29 There is reason to believe that Europe can grow faster with competitiveness reform and investment and job creation in tandem Page 25 2. Reform—much of it national—can deliver growth Page 29 1. Nurturing ecosystem for innovation Page 38 2.

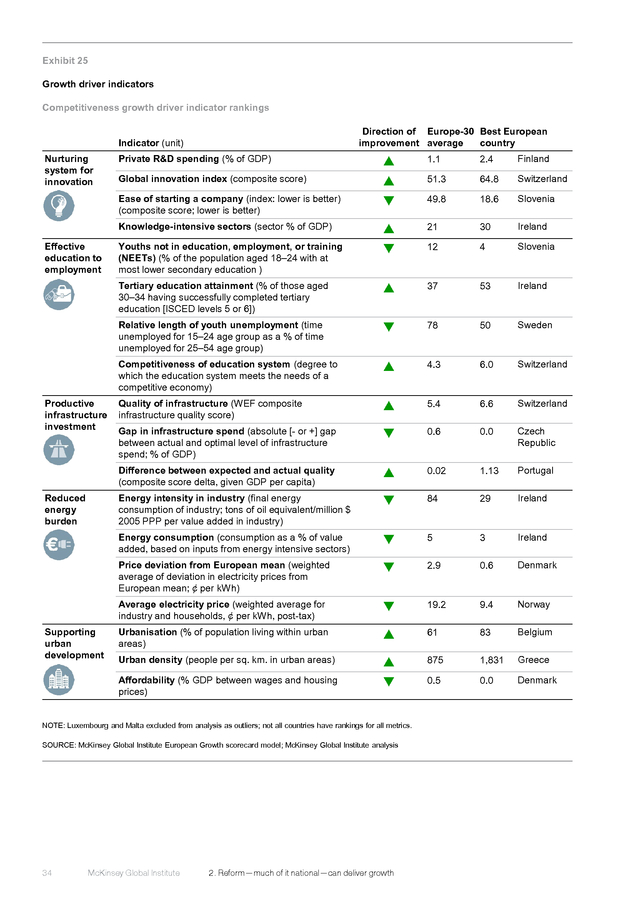

Effective education to employment Page 51 Boosting competition 143 3. Productive infrastructure investment Page 59 4. Reduced energy burden Page 68 5.

Supporting urban development Page 79 6. Competitive and integrated markets in services and digital Page 89 Stimulating demand 7. Public-sector productivity Page 101 8.

Further openness to trade Page 109 9. Grey and female labour-force participation Page 117 10. Pro-growth immigration Page 125 11.

Enhanced labour-market flexibility Page 132 3. How Europe can reignite investment and job creation Page 143 Successful reform requires productive investment and demand for jobs—and vice versa Page 144 A gap in aggregate demand persists in all domestic sectors of the economy, leaving Europe to rely on net exports Page 145 Europe has several options for igniting investment and job creation Page 161 4. Europe can overcome barriers to action Page 193 Three-quarters of competitiveness growth drivers can happen nationally with European action to boost investment and job creation Page 195 There are ways to unlock European action on investment and job creation despite governance, moral hazard, and distributional issues Page 198 Europeans are willing to play their part in their region’s economic renaissance Page 199 Appendix Page 203 Bibliography Page 229 .

IN BRIEF A WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY FOR EUROPE Europe’s growth since the start of the financial crisis has been sluggish, and the continent faces some difficult long-term challenges on demographics and debt levels. But new MGI research finds that, thanks to a convergence of low oil prices, a favourable exchange rate, and quantitative easing (QE), Europe has a window of opportunity to undertake ambitious reforms, stimulate job creation and investment, and unlock new economic dynamism.1 ƒƒ It may be tempting for some observers to write off Europe. That would be a mistake. The continent has a foundation of strength on which to take action.

It remains a world leader on key indicators of social and economic progress. And respondents polled in an MGI survey and conjoint analysis of 16,000 Europeans in eight countries had high aspirations and expressed willingness to make tough trade-offs to achieve them. ƒƒ Three areas of reform with 11 growth drivers—many of which policy makers already implement in some form—can help deliver on European aspirations. They entail investing for the future (for example, nurturing innovation and reducing the energy burden), boosting productivity (for example, competitive and integrated markets in services and digital and more openness to trade), and mobilising the workforce (for example, increasing grey and female labour-force participation and enhancing labourmarket flexibility). ƒƒ Three-quarters of the impact of growth drivers can be obtained at the national level.

Best practice on every key dimension of the economy can be found somewhere in Europe. The challenge is to emulate that best practice and adopt it more widely. ƒƒ Scope for structural reform is limited while investment and job creation are weak. Corporations are piling up cash despite low interest rates, households have cut investment since the bubble, and governments have adopted austerity policies. While every sector is acting rationally, collectively they are causing weak demand that means output is still 15 percent below pre-crisis trends. ƒƒ Europe has several options for reigniting investment and job creation despite its complex institutional setup. Measures to unlock financing and quantitative easing can help but are insufficient on their own.

Fiscal stimulus is not easy to implement at scale in Europe. New ideas need to be explored, including accounting for public investment as assets depreciate rather than during capital formation, and carefully adjusting taxation and wage structures. ƒƒ By scaling up and speeding up reform mostly at the national level and stimulating investment and job creation at the European level in lockstep, Europe could close its output gap, return to a sustained growth rate of 2 to 3 percent over the next ten years, unleash investment of €250 billion to €550 billion a year, and create more than 20 million new jobs. This requires trust and the right governance structures that avoid moral hazard, bundle tight package deals, or lift investment programmes to the European level. We define Europe in this report as the EU-28 plus Norway and Switzerland. 1 . A window of opportunity for Europe €2.2 trillion a year needed to meet European aspirations by 2025 Europeans seen willing to make trade-offs— e.g., more working hours and/or less social protection—for higher incomes and better education, health care, security, and living environment Pro-growth immigration Grey and female labour-force participation M o B an oo d 11 growth drivers In ve Nurturing ecosystem for innovation he ng t lisi bi rkforce wo kets mar ing tivity st oduc pr Enhanced labour-market flexibilty Public-sector productivity Competitive and integrated markets in services and digital Further openness to trade s ti g n Effective education to employment fo r t h e f u t u re Productive infrastructure investment Act within current governance structure where possible (e.g., QE) Test potential for a post-Maastricht governance system to enable bolder action Look at new solutions like balance sheet accounting and unleashing household spend Supporting urban development Increasing competitiveness Implementing European best practice in three key areas can deliver growth aspirations 75% can be achieved by national governments Reduced energy burden Reigniting investment and job creation Action needed to kick-start growth 15% BELOW Europe’s output is well below its pre-crisis trend Growth potential If Europe undertakes reform on the supply side AND boosts investment and job creation—moving beyond crisis management and establishing the vision, trust, and governance to act at speed and scale—2–3% sustained GDP growth is possible 2–3 growth % . Chapter photo Chapter 1: Family on steps © Getty Images Alamy . 1. EUROPE HAS A PLATFORM FOR AMBITIOUS RENEWAL A number of forces have converged over the past year to provide Europe with a window of opportunity to accelerate reform and stimulate job creation and investment that has arguably not been available since the global financial crisis began in 2008. The sudden and largely unexpected drop in oil prices, a favourable euro exchange rate, the ECB’s announcement of a QE programme, and an improving business climate all suggest that 2015 is likely to be a strong year for GDP growth (Exhibit 1). This offers a promising backdrop for an ambitious programme of renewal. Exhibit 1 Strong 2015 growth projections create a window of opportunity for Europe to commit to reform, investment, and job creation for the longer term Estimated drivers of 2015 GDP growth for Europe-30 % 1.7–1.8 0.3 0.3 ~0.9 Baseline growth 0.2 Fiscal impact of QE Depreciation of euro Decreased oil prices Projected growth, 2015 NOTE: Baseline growth rate obtained when removing buoying factors: implies weak demand/slow reform In line with 2009– 13 average of ~0.9%.

Quantitative easing (QE): assumes primary economic benefit comes from increased accrued remittances via the European Central Bank, estimated up to a maximum impact of 0.2 percent of GDP. Depreciation: based on European Commission projections in early 2015; likely to interact with QE. Oil: calculated from shift in net exports after multiplier impact.

Projected growth: based on early 2015 European Commission projections. SOURCE: IMF; European Commission; McKinsey Global Institute analysis Europe's GDP shrank by 0.1% 2007–13 It is important that Europe not interpret these improving conditions as evidence that no further action is needed to improve the competitiveness of the economy and boost investment and job creation. Its leaders need to seize the moment because this precious window may soon close. Many of these trends are temporary or could reverse.

Although recent trends have led to a cautious return to a degree of optimism about Europe’s economic prospects, the fact remains that the continent’s recovery thus far has been sluggish, and considerable challenges clearly lie ahead. Europe has clearly underperformed on its long-term growth potential since the global financial crisis, with GDP shrinking marginally by 0.1 percent between 2007 and 2013. Per capita GDP in purchasing power parity terms has only just returned to its pre-crisis peak for the continent as a whole. .

Some warn that Europe could be headed towards a deflationary spiral similar to the one Japan suffered in the 1990s. Longer term, there is apprehension that ageing will further sap the European economy’s strength and put even more pressure on governments’ finances. The prime working-age population in Europe is projected to shrink by 4 percent, or 14 million people, in the period to 2030, and by 12 percent, or 42 million people, to 2050 (there are a few exceptions to this broad trend, such as the United Kingdom). Furthermore, there are political challenges. Europeans’ trust in their governments is at very low levels, according to the Edelman Trust Barometer.1 There are worryingly high debt levels in many countries, and the stability of the Eurozone is a continuing concern. MGI’s analysis suggests that action on a broad front to mobilise the continent’s workforce and boost its productivity—with lagging European economies closing half the gap with the continent’s top-quartile performers on these two measures—could boost GDP growth to 2.1 percent a year and per capita GDP growth to 1.8 percent a year on average, with significant difference among countries. There is apprehension that ageing will further sap the European economy’s strength. Achieving a stronger society and economy will require significant resources and therefore an improvement from the lacklustre GDP growth of recent years (see Box 1, “Why GDP growth matters”).

Europe has had a tepid recovery so far. Combined with demographic headwinds and a slowdown in productivity growth since the 1990s, the European Commission estimates that annual real GDP growth will be 1.5 percent to 2025. Europe has the potential to do better than that. 1 2 2015 Edelman trust barometer, Edelman, January 2015. McKinsey Global Institute 1.

Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal . Box 1. Why GDP growth matters The debate on growth today is contentious and wide-ranging, from whether GDP is the right measure to use, to how growth can be sustainable and inclusive. We agree that GDP has serious shortcomings as a measure of growth, and we support the search for alternative measures of economic and social progress. We also acknowledge legitimate questions about how to make growth sustainable and inclusive.

However, such discussions should not distract attention from the strong empirical relationship between GDP growth and key societal goals. Growth is closely linked to employment and therefore has a direct impact on the economic livelihood of citizens. It also generates resources that can be invested to improve societal outcomes and deliver on the broader aspirations voiced in the MGI survey and conjoint analysis.

It helps societies address critical challenges such as managing public debt or, indeed, combatting environmental degradation. In fact, the link between real per capita growth and unemployment is almost mechanical. Unless growth is entirely driven by increasing labour productivity, it necessarily involves more hours worked and therefore leads to demand for more workers. For example, an analysis of European unemployment data since the 1980s shows that periods of strong growth in real per capita GDP have almost uniformly been ones when there have also been considerable reductions in unemployment. Unemployment across Europe fell continuously in the late 1980s when the rate of real per capita GDP growth consistently exceeded 2 percent per year.

As soon as real per capita GDP growth fell below this rate in the early 1990s, unemployment surged. Similar patterns occurred in subsequent years, Unemployment fell sharply in the late 1990s and mid-2000s, periods during which real per capita GDP was growing strongly. A common charge against GDP growth as a primary aim for economic policy is that it involves damaging environmental externalities. This is a multifaceted and complex issue.

An analysis of the evolution of energy consumption in advanced economies since 1970 appears to offer support for the “environmental Kuznets curve” hypothesis, which suggests that there is an inverse U-shaped relationship between economic development and environmental degradation.1 This hypothesis posits that the impact of growth on the environment decreases as economies develop and shift away from manufacturing towards services. Historically, growth in real per capita GDP in high-income economies increasingly uncouples from energy consumption. European countries including Germany, France, and the United Kingdom have reduced energy consumption while increasing real output per head (Exhibit 2).

Most European countries have reduced per capita carbon emissions since the early 2000s even while their economies were growing at a significant rate. 1 McKinsey Global Institute See, for example, Theodore Panayotou, Economic growth and the environment, presented at the spring seminar of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe in Geneva, March 3, 2003. One criticism of the environmental Kuznets curve, which is, however, not contradictory to the argument outlined here, is that the inverse U-shaped relationship may not hold any longer because countries at earlier stages of development are increasingly able to mitigate the environmental impact of growth through technology. See David I.

Stern, “The rise and fall of the environmental Kuznets curve”, World Development, volume 32, issue 8, August 2004. A window of opportunity for Europe 3 . Box 1. Why GDP growth matters (continued) Exhibit 2 Beyond a level of around $30,000, per capita GDP is largely decoupled from energy consumption Per capita energy consumption, 1970–2008 Million British thermal units (BTU) per person 250 United States 200 Australia 150 Germany France 100 Historical range for energy consumption evolution United Kingdom 50 China Japan South Korea India 0 0 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 25,000 30,000 35,000 40,000 45,000 Per capita GDP Real 2005 $ per person at purchasing power parity SOURCE: International Energy Agency; IHS; McKinsey Global Institute analysis 4 McKinsey Global Institute 1. Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal . In the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, Europe lost 6 percent of real per capita GDP in purchasing power parity terms. Real per capita GDP did not return to its pre-crisis peak until the beginning of 2015 (Exhibit 3). The path to recovery has also been uneven. It is evident that Southern European countries such as Greece and Spain will require several more years to reach their pre-crisis peaks in real per capita GDP. Surging unemployment levels have been a particularly difficult challenge in Europe.

More than five million jobs were lost across the continent between 2008 and 2013, especially in manufacturing, construction, and other industrial sectors. Exhibit 3 Europe lost 6 percent of output per head during the crisis and has only just recovered Purchasing power parity–adjusted per capita GDP1 Index: 1.00 = 1Q08 1.06 United States 1.04 1.02 1.00 Europe-302 0.98 -6% 0.96 0.94 0.92 0.90 2005 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 Expected return to pre-crisis peak Gap to pre-crisis peak, 4Q143 % Europe-30 Southern Europe 2015 ~0 ~2019 -10.4 Nordics ~2015 -1.5 United Kingdom and Ireland 2015 ~0 2014 2.2 Baltics 2011 2.9 Continental Europe Central and Eastern Europe 7.3 3.6 United States 2011 2013 1 Quarterly GDP data from Eurostat converted to 2005 purchasing power parity (PPP) in dollars using 2005 PPP from the IMF; European countries’ per capita GDP weighted with respective year population. 2 EU-28 countries plus Switzerland and Norway. 3 2014Q4 or Q3 compared with the corresponding quarter with the highest value before the financial crisis SOURCE: Eurostat; IMF; United Nations Population Division; McKinsey Global Institute analysis McKinsey Global Institute A window of opportunity for Europe 5 . Europe’s recent performance has been lacklustre Given current primary fiscal balances, interest rates, and projected real GDP growth, the ratio of government debt to GDP will continue to grow from already high levels in many European countries, including Belgium, Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom. This is a source of concern since high debt levels have historically been a drag on growth and increased the risk of financial crises that can spark another set of deep economic recessions.2 However, similarly to Japan, most major European economies will require significant fiscal adjustment before public-sector deleveraging can begin (Exhibit 4). Exhibit 4 European economies require significant fiscal adjustment to start public-sector deleveraging Primary balance—current and required1 % Primary balance, 2014 Country Spain Primary balance to start deleveraging -2.3 Japan Fiscal adjustment required ï‚¢ – Percentage points 4.9 2.6 -5.4 4.1 -1.3 Portugal 0.1 France 3.7 -2.3 2.5 0.2 Italy 1.7 United Kingdom -2.7 Finland Netherlands Belgium 1.3 Ireland 1.1 0.1 0.1 -1.0 0.8 0.7 -0.8 0.2 0.4 -0.2 Greece n/a 1.4 Germany 1.9 1.9 -0.3 -1.0 United States 3.6 -0.8 -1.6 3.6 0.0 2.7 2.1 n/a n/a 1 Based on consensus GDP forecast, current inflation, 2Q14 government level of debt to GDP, and estimated 2014 effective interest rate. SOURCE: McKinsey Country Debt database; IMF; IHS; EIU; Oxford Economics; OECD; McKinsey Global Growth Model; McKinsey Global Institute analysis 2 6 Debt and (not much) deleveraging, McKinsey Global Institute, February 2015. McKinsey Global Institute 1. Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal . Other major trends appear worrying for Europe’s future, too. Youth unemployment remains stubbornly high, hovering just under the 20 percent mark across the EU. Unless this problem is tackled, there is a risk of rising popular unrest. Meanwhile, the risk of populist parties gaining power and calling for the dissolution of the EU has grown.

Such political groupings gained significant shares of the vote in the 2014 EU elections. The stability of the euro and the future of the Eurozone remain subject to concern and conjecture. Greek deposit outflows reached €500 million a day at some points during early 2015.

At the time of writing, it is unclear whether Greece will continue to be a member of the Eurozone and the EU. On top of all of these factors, Europe is ageing, placing pressure on the pool of available labour. The European Commission expects that, by 2060, Germany’s population will shrink by one-fifth, and the number of Germans of working age from 54 million in 2010 to 36 million in 2060—lower than the total in France.3 Taking all of this together adds up to a dismal picture of Europe’s future. Without urgent reform, Europe could be on a dangerous path. Europe's real GDP grew only 1.1% per annum 2009–12 and 0.2% in 2013 Europe’s anaemic recovery was reflected in real GDP-growth rates.

Between 2009 and 2012, real GDP in Europe grew at a rate of only 1.1 percent per year. In 2013, real GDP growth even decelerated to 0.2 percent. This trajectory was significantly weaker than the rate observed in past European expansions and has also fallen short of post-crisis growth in other advanced economies.

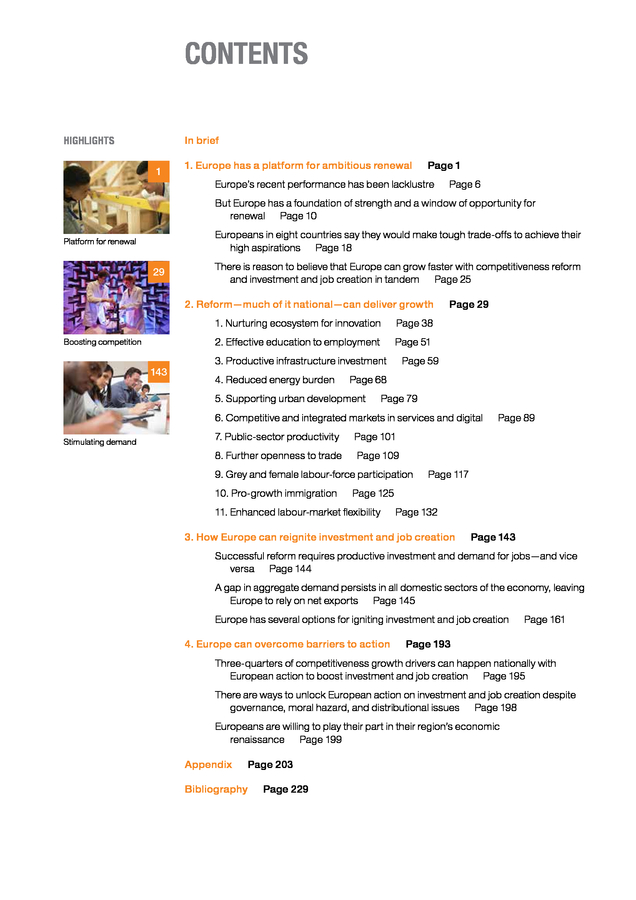

Many analysts and commentators even warn that, seven years on from the onset of the crisis, Europe still risks entering a deflationary spiral and a long period of stagnation as Japan has experienced since the crisis of the early 1990s.4 Taking a broader view of Europe’s GDP growth beyond the relatively narrow focus on the 2008 global financial crisis and its aftermath, we find that Europe’s growth performance has been declining since the 1990s (Exhibit 5). This reflects trends in the supply of labour (or total hours worked) and productivity, the two principal forces behind real GDP growth. From 1995 to 2000, a period when real GDP growth averaged 2.9 percent a year in Europe, 0.9 percentage points came from an increase in the total number of hours worked and the other two percentage points from increased output per hour worked, or labour productivity. Between 2000 and 2007, real GDP growth per annum dropped to 2.3 percent.

The hours worked component continued to contribute one percentage point, but growth in labour productivity declined to 1.3 percent per annum. Between 2007 and 2013, hours worked made a slightly negative contribution to growth, and the contribution of productivity growth also weakened sharply to only 0.2 percent per annum. This collapse partly reflected the impact of the financial crisis.

Considering only the post-crisis period between 2009 and 2013, annual productivity growth recovered to a rate of 1.2 percent, while the contribution of hours worked remained negative. However, the fact remains that Europe will need to improve its performance on both key drivers of GDP growth if that measure is to settle back into a more robust upward trajectory. Looking at hours worked, Europe faces a projected decline in the number of 15- to 64-yearolds from 340 million in 2013 to 326 million in 2030. In the period to 2050, Europe’s labour force is expected to shrink even more dramatically (Exhibit 6).

Our analysis finds that this trend could dampen real GDP growth by around 0.2 percent a year over the next ten years. To offset the impact of declining population growth on the labour pool and therefore real GDP growth, Europe should consider action to boost the participation of women and older workers and should consider shifts in immigration policy with an explicit view to boosting growth. The 2012 ageing report: Underlying assumptions and projection methodologies, European Commission, April 2011. 4 For an overview of the recent debate on “secular stagnation”, see Coen Teulings and Richard Baldwin, eds., Secular stagnation: Facts, causes and cures, Centre for Economic Policy Research, August 2014. 3 McKinsey Global Institute A window of opportunity for Europe 7 . Exhibit 5 Europe's growth performance has been declining since the 1990s Decomposition of annual growth performance % 1995–2000 2000–07 2007–13 Labour Labour productivity Real GDP Increasing overall population 2.0 2.9 -0.2 1.3 Europe-30 2.3 -0.4 -0.1 -0.2 4.3 Real per capita GDP -1.2 2.7 0.9 1.9 1.0 -0.3 0.2 2.5 United States -0.3 3.1 1.8 1.7 2.4 -0.9 1.5 0.7 1.1 1.0 -0.8 0.2 -0.1 0.9 0.8 -0.2 0.6 1.4 1.4 -0.1 1.3 0.1 Japan 0.1 0.2 -0.1 0 -0.4 0.5 SOURCE: Eurostat; World Bank World Development Indicators; McKinsey Global Growth Model; McKinsey Global Institute analysis 8 McKinsey Global Institute 1. Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal . Exhibit 6 Europe’s prime working-age population is in a steep long-term decline, dropping by a projected 42 million between 2013 and 2050 Europe-30 prime working-age population (15- to 64-year-olds), 1990, 2013, 2030, and 20501 Million Baltics Nordics United Kingdom and Ireland 326 15 340 5 17 40 4 44 326 17 4 45 298 18 Compound annual growth rate, 2013–50 % 3 -0.7 0.2 68 67 46 0.2 50 Central and Eastern Europe -0.8 69 -0.6 -0.3 61 Southern Europe 79 85 Continental Europe 120 123 117 111 1990 2013 2030 2050 81 1 Includes immigration. NOTE: Numbers may not sum due to rounding. SOURCE: United Nations Population Division; McKinsey Global Institute analysis Given the end of demographic tailwinds in Europe, the onus will be on productivity to drive growth. Even the recovery in productivity growth to 1.2 percent per annum between 2009 and 2013 leaves the rate of productivity growth relatively weak, suggesting room for improvement. Our analysis of long-term labour productivity growth in leading economies since 1800 finds a long-term average rate of productivity growth of 1.4 percent per annum (with large variations around that average) (Exhibit 7). Historically, every period of weakening productivity growth has been followed by a rebound to above-trend growth.

This was the case in the years after the Great Depression in the 1930s and the oil crisis in the 1970s, for instance. However, in the recovery from the global financial and economic crisis, this has not been the case. The rate of annual productivity-growth rate since 2009 has remained significantly weaker than in the late 1990s, when it was 2 percent a year on average. Europe is not alone in experiencing weakening productivity growth; a similar trend can be observed in other advanced economies.

For instance, US productivity growth was 2.5 percent a year from 1995 to 2000 but only 1.5 percent between 2009 and 2013. Nevertheless, Europe will have to find ways to reignite productivity growth in order to achieve a more promising economic outlook. McKinsey Global Institute A window of opportunity for Europe 9 . Exhibit 7 Productivity per worker has historically grown at 1.4 percent a year with significant variation around that average Growth of GDP1 per labour force worker,2 ten-year rolling growth3 % Productivity Period average Long-term average Second Industrial Revolution: electrical DC motors, telephone, typewriter, industrial capital formation 3.0 2.5 1.5 Deregulation and globalisation Roaring Twenties: mass production, especially automobiles Railroad, steam engine proliferation 2.0 Mass education, urbanisation Further electrification New economy 1.9 2.0 1.4 1.4 1.2 1.0 0.5 0.3 Great Depression 0.2 0 1800 10 20 30 40 50 Pre-railroad 60 70 80 90 1900 10 Rapid industrialisation 20 30 40 World Wars I and II 50 60 70 Postwar prosperity Bretton Woods 80 Oil crisis 90 00 2009 Great Moderation (deregulation) 1 Highest GDP per worker among group of companies shown; United Kingdom to 1879; United States from 1880. 2 Working-age population is very rough estimate derived from total population and life expectancy. Labour force derived from OECD and International Labour Organisation data from 1960 and assumed 58% before industrialisation (interpolation in between); 55% assumes 95% male participation and 15% female participation. We do not consider unemployment. 3 1939–45 and 1914–24 periods linearly interpolated; highest achieved GDP per worker kept constant during recessions/negative growth. SOURCE: Angus Maddison series; OECD; United Nations; Gapminder; McKinsey Global Institute analysis But Europe has a foundation of strength and a window of opportunity for renewal An ambitious programme of renewal is possible because Europe has fundamental strengths. It is one of the world’s largest economies, home to a huge, highly integrated domestic market of 500 million inhabitants.

It also is well connected to global flows and is home to half of the 20 most competitive economies in the world, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF). European economies remain world leaders on six dimensions of social progress and perform well on indicators of economic health. Indicators of economic health and societal wellbeing correlate strongly (Exhibit 8). While the causation between societal well-being and economic health is likely to run both ways, getting Europe’s economic house in order will be necessary to build a healthier society and meet Europeans’ ambitions. 10 McKinsey Global Institute 1.

Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal . Exhibit 8 Strong economic performance creates the foundation for improved societal outcomes Nordics Continental Europe United Kingdom and Ireland Southern Europe Baltics Central and Eastern Europe Societal well-being Z-score composite index, Europe-30 = 0 0.7 0.6 R-squared = 45% Denmark 0.5 0.4 Malta 0.3 Ireland 0.2 0.1 0 Cyprus Slovenia Sweden Germany Belgium Netherlands Finland Switzerland Luxembourg Austria France Spain Italy -0.1 United Kingdom Czech Republic -0.2 -0.3 Portugal -0.4 -0.5 -0.6 Norway Hungary Greece -0.7 Estonia Croatia Lithuania -0.8 Latvia Slovakia Poland -0.9 -1.0 Bulgaria -1.1 Romania -1.2 -1.3 -1.4 -1.3 -1.2 -1.1 -1.0 -0.9 -0.8 -0.7 -0.6 -0.5 -0.4 -0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 Economic health Z-score composite index, Europe-30 = 0 SOURCE: Eurostat; OECD; UNESCO; UNODC; World Bank, WEF; WHO; CIA; national statistical offices; McKinsey Global Institute analysis To measure economic health, we use a composite index comprising five elements: prosperity, inclusiveness, agility, resilience, and connectedness (see Exhibit 9 for details on the indicators included in this measure). Countries including Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland that score highly on economic health have also performed strongly on the six dimensions of societal well-being we have detailed. Conversely, societal well-being indicators are below the European average in many countries whose economic performance has been weaker, including Greece, Portugal, Romania, and Slovakia. McKinsey Global Institute A window of opportunity for Europe 11 . Exhibit 9 Europe’s economic performance is more varied than its social performance, but the continent still boasts best practice Performance on attributes relative to Europe-30 average Composite indicators; ranges of country-level z-scores1 United States Europe-30 Countries with top indicator scores2 Population >1 million European average Norway Prosperity -1.1 Switzerland 1.2 United States Norway Inclusiveness -1.2 Switzerland 1.3 Japan Economic health United States -1.3 Agility 1.9 Japan Sweden Czech Republic -1.4 Resilience 1.0 Sweden Australia Connect-2.4 edness Germany 0.7 United States United Kingdom 1 Measurement of the number of standard deviations away from the mean. The selection of subindicators and metrics, of course, influences country scores; not all countries have rankings for all metrics. 2 Comparison among Europe-30 countries, Australia, Canada, Japan, South Korea, and the United States. SOURCE: Eurostat; OECD; UNESCO; UNODC; World Bank; WEF; WHO; CIA; national statistical offices; McKinsey Global Institute analysis On each of the five elements of economic health, it is only on inclusiveness that Europe, on average, outperforms the United States. Performance across the continent varies widely. For example, per capita GDP at purchasing power parity in Switzerland is more than three times that of Bulgaria. Productivity per hour in Norway is more than 12 times that of Romania.

Debt-to-GDP ratios in Europe’s public and private sectors range from 109 percent in Latvia to almost 450 percent in Ireland. Nevertheless, it is promising that at least one individual European economy represents best practice on each of the five dimensions. Norway and Switzerland are leaders on prosperity and inclusiveness, Sweden on agility, the Czech Republic and Sweden on resilience, and Germany and the United Kingdom on connectedness. If all European countries were to match the performance of the front-runners on each dimension, a much more robust continental economy would be created.

Furthermore, some European economies have made progress in the past few years on crucial structural policies needed to underpin future growth (Exhibit 10). This gives cause for optimism that such efforts can—as they must— continue at an accelerated pace.5 5 12 Economic policy reforms 2015: Going for growth, OECD, 2015. McKinsey Global Institute 1. Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal .

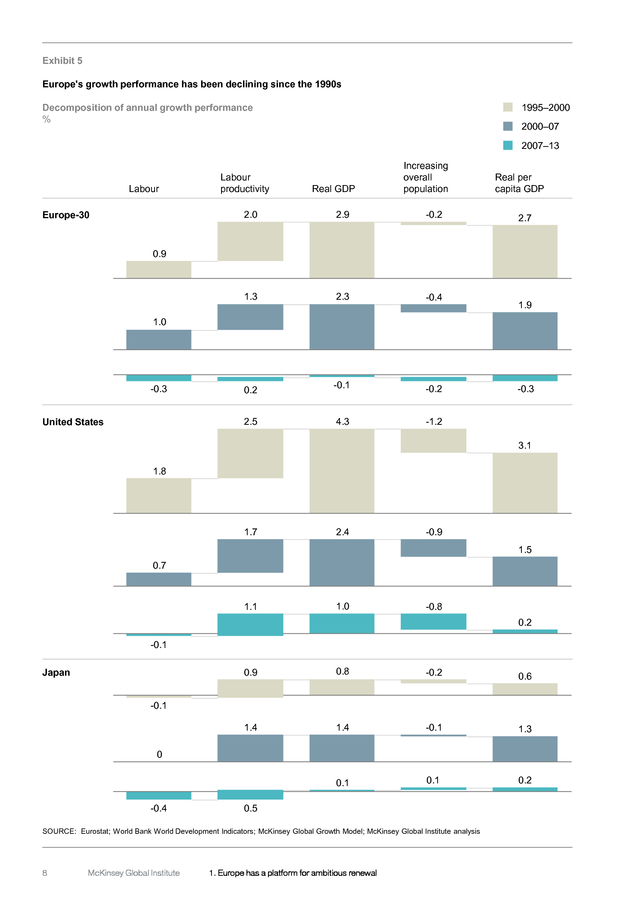

Exhibit 10 Economic progress indicators Economic health indicator rankings Indicator (unit) Prosperity Direction of Europe-30 improvement average Best practice ï° 147,975 379,550 Switzerland ï° 47.1 86.6 Norway ï° -821 2,611 Poland Employment to working-age population (ratio of those employed to overall working-age population) ï° 0.51 0.66 Norway Gini, post-tax, post-pensions (distribution of family income; Gini index – measure of inequality) ï± 0.31 0.23 Norway Ratio of highest to lowest income decile ï± 9.4 5.3 Czech Republic Wage share of GDP (adjusted wage share, % of GDP) ï° 56 69 Switzerland Entrepreneurship index (index of development of entrepreneurship) ï° 57 74 Sweden Patents per million capita (per year) ï° 48 164 Switzerland R&D expenditure (R&D spending, % of GDP) ï° 1.8 3.6 Finland Debt-to-GDP ratio (overall debt as % of GDP; excluding debt from financial corporations) ï± 245 109 Latvia Financial rating (composite financial rating of multiple economic indexes and credit agency scores) ï° 77.8 99.5 Switzerland Performing loans (non-performing loans, % of total bank loans) ï° 92 100 Finland Dependency ratio increase (percentage point change in ratio of the size of the over-65 population to 15- to 64-year-old population, 2014–35) ï± 15 5% Latvia Sectoral concentration (Herfindahl index: methodology to assess sectoral diversification) ï± 0.06 0.05 Czech Republic MGI connectedness index: goods ï± 18 3 Germany MGI connectedness index: services ï± 18 1 Ireland MGI connectedness index: finances ï± 33 7 Germany MGI connectedness index: people ï± 24 5 Germany MGI connectedness index: data Connectedness (global ranking: lower absolute figure is better) 62,858 Per capita GDP growth (change in GDP per capita, 2008–13, constant 2011 $) Resilience 33,747 Productivity per hour (real output [measured in deflated GDP] per hour of labour input, $) Agility ï° Net wealth per capita (net wealth per adult: assets less liabilities, $) Inclusiveness Per capita GDP (constant 2011 $, at purchasing power parity) ï± 11 1 Netherlands Norway NOTE: Luxembourg and Malta excluded from analysis as outliers, not all countries have rankings for all metrics. SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute European Growth scorecard model; McKinsey Global Institute analysis McKinsey Global Institute A window of opportunity for Europe 13 . Germany 1ST in world on global connections While the current debate on the European economy tends to focus on the negative, it is important not to gloss over the continent’s genuine economic strengths. Europe is one the world’s largest economies, accounting for 24 percent of global GDP in 2012, ahead of the United States at 22 percent.6 The process of European economic integration has created a single market of more than 500 million inhabitants with a largely free flow of goods and capital across the European Economic Area. European nations are not only closely connected with one another, but also more connected into global flows than many other parts of the world, including emerging and rapidly growing markets such as China, India, and Brazil. On MGI’s Connectedness Index, Germany is ranked first in the world, with the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and France ranked fifth to seventh, respectively (Exhibit 11).7 Exhibit 11 Europe is one of the world’s largest economies and is more connected to global cross-border flows than other major economies Share of nominal world GDP at market exchange rates, 2012 100% = $73.6 trillion Rest of world 22 26 North America1 India 3 Russia 3 Brazil 3 Japan 8 24 11 China Europe-30 MGI Connectedness Index, 20122 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 … 21 25 27 30 43 Germany Hong Kong, China United States Singapore United Kingdom Netherlands France Canada Russia Italy Belgium Spain Switzerland Ireland Sweden … Japan China Mexico India Brazil 1 Canada, Mexico, and the United States. 2 Global flows in a digital age: How trade, finance, people, and data connect the world economy, McKinsey Global Institute, April 2014. SOURCE: World Bank; McKinsey Global Institute analysis North America—Canada, Mexico, and the United States—accounts for 27 percent of global GDP. Global flows in a digital age: How trade, finance, people, and data connect the world economy, McKinsey Global Institute, April 2014. 6 7 14 McKinsey Global Institute 1.

Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal . According to the WEF, ten of the 20 most competitive economies in the world are located in Europe, with Switzerland topping the global ranking.8 The continent is also home to many world-class companies, including 142 Fortune 500 companies as of 2014, more than the 128 based in the United States. Particular strengths can be found in knowledgeintensive industries.9 Twenty-nine of the world’s most innovative companies in 2014 listed by Forbes magazine are headquartered in Europe.10 Europe retains major trade surpluses in knowledge-intensive manufacturing and services (2.8 percent and 1.4 percent of GDP, respectively, for the EU-15 in 2012). Combined with the right policies and priorities, these achievements can be the bedrock for a more robust future economic performance. There is scope to improve all five dimensions of economic health. The key indicator of whether those improvements are made will be GDP growth.11 Europeans enjoy a high quality of life The quality of life in European societies is very high.

Out of six widely recognised measures of social progress—health care, education, the living environment, public safety, social protection, and work-life balance—Europe scores on average higher than the United States on four (Exhibit 12). The views expressed by the Europeans surveyed on what it takes to have a better life are broadly similar to those of citizens of other advanced economies, according to online responses received on the website of the OECD’s Better Life Index.12 Like people in Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and the United States, Europeans tend to place emphasis on overall life satisfaction, health, and education. These are dimensions on which many European countries perform strongly. <3% of employees in Denmark, Netherlands, and Norway work >50 hours a week However, there is a great deal of variation within Europe on these social metrics (Exhibit 13). Some countries outperform other nations around the world by a considerable margin; others underperform. For example, Norway ranks in the top three of a peer group of advanced economies on education, public safety, and work-life balance.13 Denmark, the Netherlands, and Norway are the top performers on work-life balance.

In these three countries, people devote 15.6 to 16.1 hours a week to leisure and personal care, and less than 3 percent of all employees work more than 50 hours per week. In our set of countries and chosen set of metrics, Spain is Europe’s leading performer on health care and Germany is Europe’s leader on education. The high degree of variation in performance within Europe on these six quality-of-life indicators and the presence of world-leading examples on each of the six send an important message. Europe may have experienced several years of difficult economic conditions since the global financial crisis in 2007 and global recession in 2008, but it still boasts a high quality of life overall and is home to world leaders on different measures of social progress. Europe can look within its borders for the solution to the future. The global competitiveness report 2014–15, World Economic Forum, September 2914. Knowledge-intensive goods and services are those that have a high R&D component or utilise highly skilled labor. 10 “The world’s most innovative companies”, Forbes, August 2014. 11 We fully acknowledge the many measurement challenges and conceptual shortcomings associated with GDP and welcome the many initiatives under way to refine and broaden the measurement of growth.

For further discussion, see Global growth: Can productivity save the day in an aging world? McKinsey Global Institute, January 2015. 12 Better Life Index, OECD, 2014. 13 Comparisons include the Europe-30 plus Australia, Canada, Japan, South Korea, and the United States. 8 9 McKinsey Global Institute A window of opportunity for Europe 15 . Exhibit 12 Despite recent challenges, Europe remains a world leader on various indicators of social progress Performance on attributes relative to Europe-30 average Composite indicators; ranges of country-level z-scores1 United States Europe-30 Countries with top indicator scores2 Population >1 million European average Spain Health care 1.2 -1.5 Australia Switzerland Germany Education -1.2 0.8 Finland Norway Sweden Living environment -1.7 Finland 1.1 Portugal Societal well-being Norway Public safety -1.4 Austria 1.1 Switzerland Social protection Work-life balance Ireland Germany 1.1 -2.0 Austria Denmark -1.4 1.6 Netherlands Norway 1 Measurement of the number of standard deviations away from the mean. The selection of subindicators and metrics, of course, influences country scores; not all countries have rankings for all metrics. 2 Comparison among Europe-30 countries, Australia, Canada, Japan, South Korea, and the United States. SOURCE: Eurostat; OECD; UNESCO; UNODC; World Bank; WEF; WHO; CIA; national statistical offices; McKinsey Global Institute analysis 16 McKinsey Global Institute 1. Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal . Exhibit 13 Social-progress indicators Societal well-being indicator rankings Indicator (unit) Health Life expectancy at birth (years) Direction of Europe-30 improvement average Best practice ï° 80 83 Italy Healthy life expectancy at birth (healthy life expectancy at birth [years] ÷ life expectancy at birth [years], % of total) ï° 87.9 90.2 Cyprus Infant mortality rate (deaths per 1,000 births) ï± 3.8 1.6 Slovenia Self-reported good health (self-reported responses describing good or very good health, %) ï° 68 82 Switzerland Mortality from ischaemic heart disease (deaths per 1,000 population, age-adjusted) ï± 104 48 France ï° 498 529 Finland Preschool enrolment rate (% of children aged 3–5 enrolled in preschool/kindergarten) ï° 88 100 France Competitiveness of education system (degree to which the education system meets the needs of a competitive economy) ï° 4.30 6.0 Switzerland Matching of skills (indexed measure of over- or undereducation in workforce) ï± 0.97 0.63 Norway Vocational training attainment (25- to 64-year-olds attained upper-secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education, %) ï° 46 72 Czech Republic Carbon dioxide emissions per GDP unit (kilotonnes of CO2 emissions per € million GDP) ï± 0.36 0.09 Switzerland Particulates per cubic metre (PM10, country level [micrograms per cubic meter]) ï± 27.9 15.8 Finland Housing quality (composite based on dwelling quality, housing expenditure, and rooms per person) ï° 100.4 102.2 Norway UNESCO cultural heritage sites (sites per 100,000 sq km land area) ï° 10.2 32.8 Belgium Non-congestion rate (ratio of average to free-flow speed, scores averaged across three speed limit zones) ï° 0.90 0.93 Czech Republic Homicide rate (intentional homicides per 100,000 people) ï± 1.1 0.6 Austria Rule of law (index score on perceived quality) ï° 3.7 4.5 Norway Political stability (index score on perceived quality) ï° 3.1 3.9 Switzerland ï± 12 3 Estonia ï° 55 91 Austria Social protection expenditure (total public social expenditure as % of GDP) ï° 28 35 Denmark Redistribution (observed delta between pre-tax/pensions Gini and post-tax/pensions Gini coefficients) ï° 0.19 0.27 Ireland Average time worked (hours worked per year per person employed) ï± 1,638 1,380 Netherlands Employees working long hours (% of employees working more than 50 hours per week) ï± 7 1 Netherlands Time devoted to leisure and personal care (hours per week) ï° 15.1 16.1 Denmark Education Average PISA score (maths, science, reading) Living environment Public safety Social Vulnerable employment (% of total employment) protection Unemployment benefits (coverage of contributory and non-contributory schemes, %) Work-life balance NOTE: Luxembourg and Malta excluded from analysis as outliers; not all countries have rankings for all metrics. SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute European Growth scorecard model; McKinsey Global Institute analysis McKinsey Global Institute A window of opportunity for Europe 17 . Europeans in eight countries say they would make tough trade-offs to achieve their high aspirations While Europe is already a world leader on many dimensions of social progress, and Europeans generally enjoy an enviable quality of life even in comparison with citizens of other high-income countries and regions, they are not content merely to preserve these accomplishments. People in eight countries surveyed by MGI express a desire for an even better deal and are willing to make tough trade-offs to secure one. This is a key theme that emerges from a conjoint survey of 16,000 respondents in eight European countries, conducted by the McKinsey Global Institute in August 2014. The survey asked respondents to reflect on aspirations and priorities for their societies over the next ten years.14 While we acknowledge that what people say in response to survey questions may not entirely reflect the way they would vote when presented with actual policy options, we believe that the results offer an indication of attitudes across eight European countries that may be useful intelligence for decision makers. MGI’s survey asked respondents to make tangible trade-offs in order to secure an even higher quality of life (see Box 2, “Conjoint-survey methodology”, and the appendix for a detailed description of the survey and the methodology used, as well as the limitations). The survey found that individuals express broad agreement that even greater effort and resources should be invested in specific areas. 14 MGI conducted a survey among 2,000 participants each in France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Romania, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Respondents were asked to choose between sets of conjoint scenarios that trade off a desire to have more or less of different attributes of societal aspirations in a cost- or GDPbalanced way.

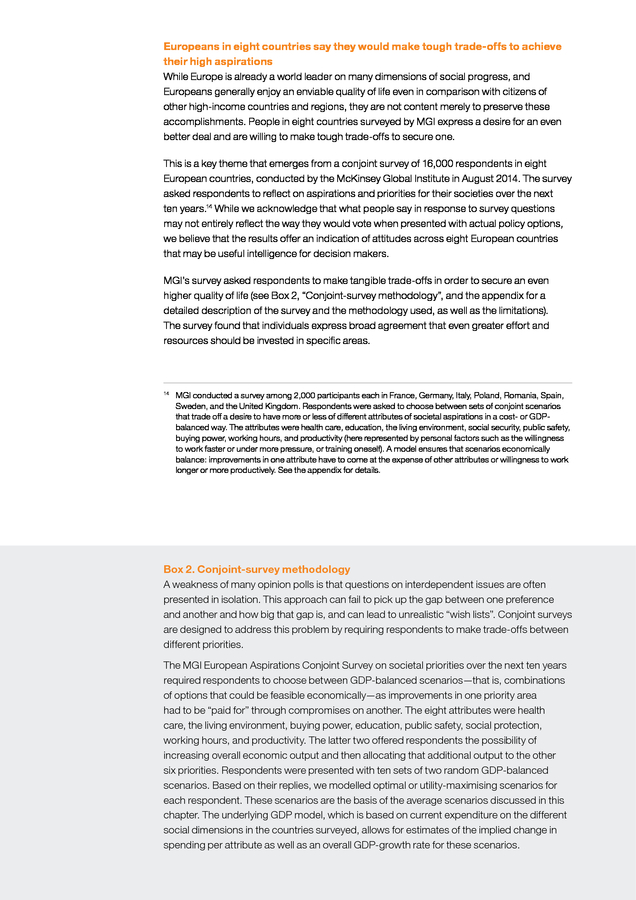

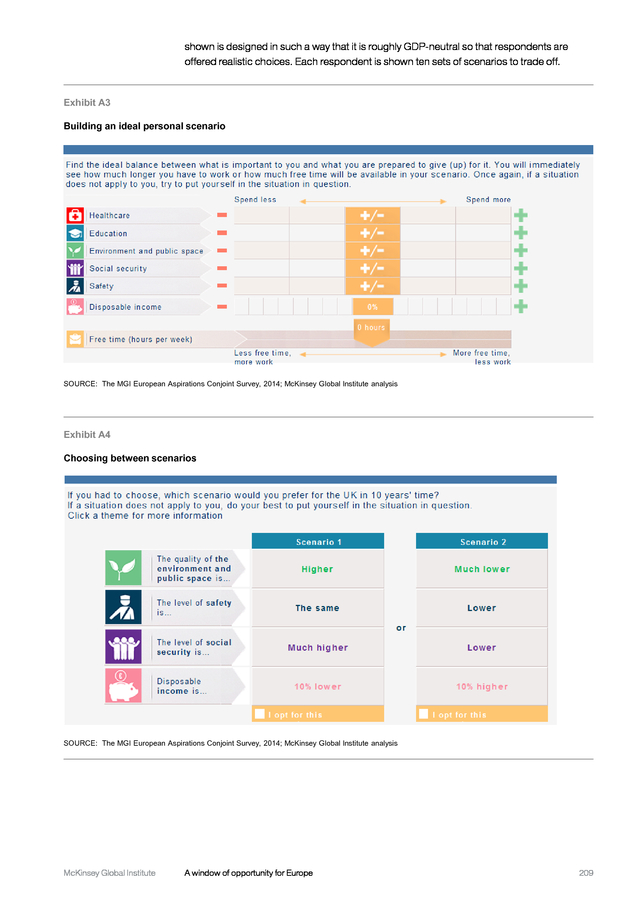

The attributes were health care, education, the living environment, social security, public safety, buying power, working hours, and productivity (here represented by personal factors such as the willingness to work faster or under more pressure, or training oneself). A model ensures that scenarios economically balance: improvements in one attribute have to come at the expense of other attributes or willingness to work longer or more productively. See the appendix for details. Box 2.

Conjoint-survey methodology A weakness of many opinion polls is that questions on interdependent issues are often presented in isolation. This approach can fail to pick up the gap between one preference and another and how big that gap is, and can lead to unrealistic “wish lists”. Conjoint surveys are designed to address this problem by requiring respondents to make trade-offs between different priorities. The MGI European Aspirations Conjoint Survey on societal priorities over the next ten years required respondents to choose between GDP-balanced scenarios—that is, combinations of options that could be feasible economically—as improvements in one priority area had to be “paid for” through compromises on another.

The eight attributes were health care, the living environment, buying power, education, public safety, social protection, working hours, and productivity. The latter two offered respondents the possibility of increasing overall economic output and then allocating that additional output to the other six priorities. Respondents were presented with ten sets of two random GDP-balanced scenarios.

Based on their replies, we modelled optimal or utility-maximising scenarios for each respondent. These scenarios are the basis of the average scenarios discussed in this chapter. The underlying GDP model, which is based on current expenditure on the different social dimensions in the countries surveyed, allows for estimates of the implied change in spending per attribute as well as an overall GDP-growth rate for these scenarios. 18 McKinsey Global Institute 1.

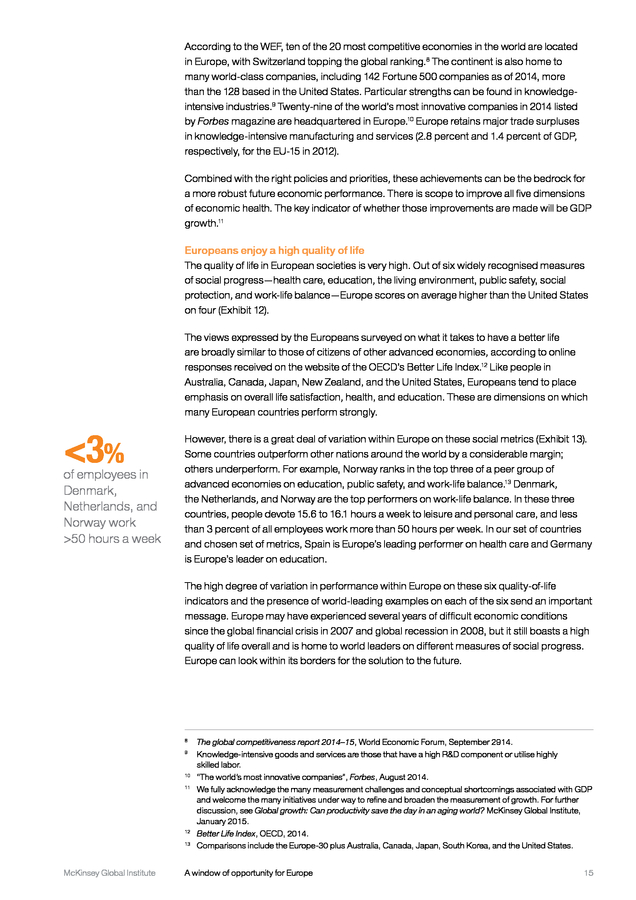

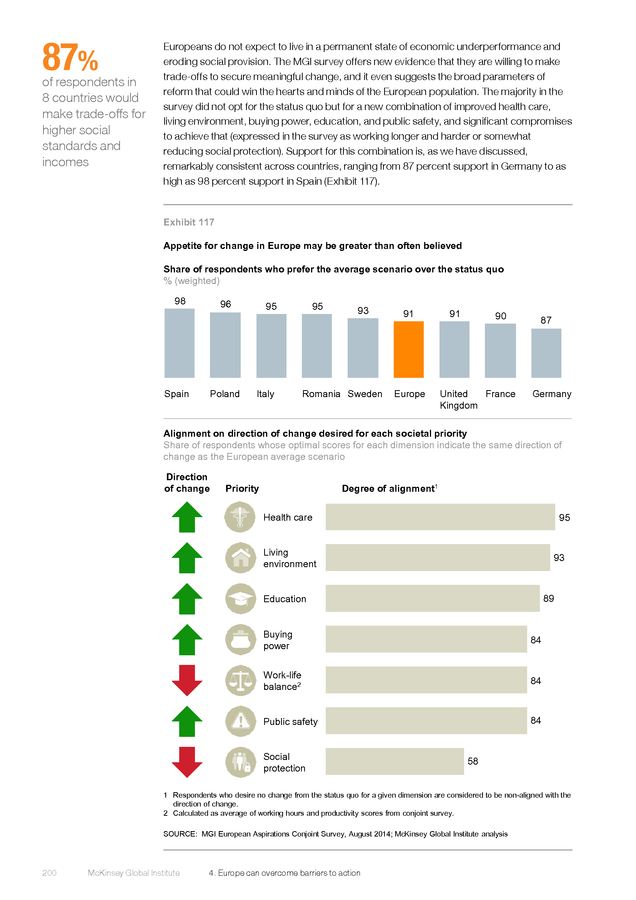

Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal . Respondents across countries, age groups, and levels of income and educational attainment express a common desire for additional investment in health care, the living environment, education, and public safety in the period to 2025, and at the same time say they want to increase their disposable income. The survey suggests that, on average, respondents would prioritise improvements in health care, the living environment, education, and public safety, and they would be willing to “pay” for these improvements by deprioritising their work-life balance and social protection (Exhibit 14). Those surveyed say that, to achieve improvements in these key social measures and rising incomes, they would be prepared to work longer—in the order of 1.8 hours a week (0.5 hours to three hours depending on the country)—and more productively, and to accept a reallocation of spending away from social-protection programmes. Specifically, the survey shows that 84 percent of respondents say that they would be willing to compromise on their work-life balance as long as this led to improved societal outcomes and higher individual incomes—the opposite of the image of a “lazy European”. It is important to note that, although respondents say they are prepared to invest additional effort to achieve improvements in their priorities for society as a whole, they also express a wish to see growth in their individual incomes—captured in the survey by “buying power”. To realise improvements in health, the living environment, education, public safety, and buying power, additional resources of €2.2 trillion a year would be required by 2025, equivalent to 15 percent of Europe’s current GDP. The survey shows that 84 % of respondents say that they would be willing to compromise on their worklife balance as long as this led to improved societal outcomes and higher individual incomes. 96% of respondents want improved health care 93% of respondents want improved living environment McKinsey Global Institute Respondents’ aspirations and commitments are broadly shared across Europe The priority the Europeans we surveyed give to improvements in the different dimensions of social progress is remarkably consistent.

While our survey does not adjust for cultural biases, it is notable that people in all eight countries agree on the areas where they would like to see improvements, namely health care, the living environment, education, and public safety. They all want their incomes to rise, too (Exhibit 15). There is very little variation in the ranking of these priorities among different age groups, educational levels, employment status, and income levels.

In each of these key social areas, more than 80 percent of all respondents expressed a common desire for improved outcomes, with almost unanimous agreement that improvements should be made with respect to health care and the living environment (96 percent and 93 percent agreement, respectively). A window of opportunity for Europe 19 . Exhibit 14 European survey respondents want improvements to measures of societal well-being and buying power— and are ready to make trade-offs to achieve them Results of MGI European Aspirations Conjoint Survey Aspirations and trade-offs of respondents in eight European countries to 2025 based on GDP-balanced conjoint analysis1 Conjoint survey responses, n = 16,000 Relative strength of preferences for different social outcomes Much less Less Same More Much more Health care Living environment Buying power Education Public safety Work-life balance2 Social protection Allocation of resources in respondents' preferred scenario Additional spend and income generation Living environment Public safety Health care 1.8 hours per week per worker—a commitment broadly shared by those in full-time, part-time, or no employment3 Education Buying power Additional spend and income Productivity increase Working longer (extra hours) Working more productively Spending reallocation from social protection to other priorities 91% of respondents would prefer this scenario over the status quo 1 Averaged GDP- and demographic-weighted optimal levels for each respondent. 2 Calculated as average of working hours and productivity scores from conjoint survey. 3 Calculated based on choices of all respondents irrespective of current employment status; current full-time employees would choose to work 1.6 hours longer on average. There is a significant spread among countries. SOURCE: MGI European Aspirations Conjoint Survey, August 2014 (N = 16,000); McKinsey Global Institute analysis 20 McKinsey Global Institute 1. Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal . Exhibit 15 Countries are aligned on most priorities, although opinion differs on the trade-off between work-life balance and social protection Desired change from status quo for country-specific “average” scenarios1 Weighted average deviation from status quo Germany Sweden United Kingdom France Italy Spain 26 24 Poland Romania Health care Living environment Buying power Education Public safety Work-life balance Social protection Purchasing power parity–adjusted real per capita GDP, 2012 € thousand 34 33 29 29 19 12 1 The “average” scenario takes averaged GDP- and demographic-weighted optimal levels for each respondent. SOURCE: MGI European Aspirations Conjoint Survey, August 2014; McKinsey Global Institute analysis The survey also revealed a shared readiness to work longer and more productively across geographies—and not only among those currently deprived of opportunities to work because of the economic environment. However, there is some variation among respondents on how to achieve this shift (Exhibit 16). For example, the survey found that Polish respondents expressed a preference for generating additional output mainly through significant productivity improvements but increasing their working hours by only a relatively modest 1.1 weekly hours per worker. In contrast, French respondents as a group said that they would be willing to work as much as 2.0 more hours a week while slightly decreasing productivity.

It is in Spain and Italy that respondents appear most willing to make large compromises on both aspects of their work-life balance for societal improvements and their incomes. The survey results show that, on average, Spanish respondents would accept working an extra 2.7 hours per week and working much more productively. On average, Italian respondents say that they would be prepared to work 2.5 additional hours a week and much more productively.

At first glance, these results may appear to reflect that fact that Spain and Italy have been facing particularly difficult economic conditions. However, the results also largely hold for Spanish and Italian respondents who are in fulltime employment. McKinsey Global Institute A window of opportunity for Europe 21 . Exhibit 16 Readiness to work longer and more productively to improve societal outcomes is common to most countries with some variations Extra hours worked Number Productivity increase Relative preference Less More Much more 2.7 Spain Italy 2.5 Romania 2.0 1.1 Poland 1.6 Germany 1.3 United Kingdom France Same 1.8 Europe Sweden AVERAGE SCENARIO 0.5 2.0 SOURCE: MGI European Aspirations Conjoint Survey, August 2014; McKinsey Global Institute analysis 72% of respondents would work longer In practice, any commitment among Europeans to compromise on their work-life balance could be achieved in several ways. Reducing holidays, delaying retirement, or bringing unemployed people into work could have a similar impact to extending the working week by 1.8 hours. The survey found that, if they were personally required to work more, the top choice of 54 percent of respondents in full-time employment would be to work more hours each week; 23 percent of this group would choose to forfeit holidays or delay retirement. In all eight countries surveyed, working more hours per week was the top choice among respondents, although that preference was more prevalent in some countries than in others. For instance, 64 percent of respondents in France indicated that they would prefer to work more hours per week compared with only 44 percent of respondents in the United Kingdom, where 35 percent of respondents chose later retirement as their preferred option. Many respondents expressed willingness to work longer hours not solely as a necessary trade-off to achieve better social outcomes but also as an intrinsically positive choice if doing so would increase their disposable income.

The survey asked separate questions about how long respondents were currently working and how long they would be willing to work if compensated accordingly. The survey found that 72 percent of respondents currently employed opted for increased working hours. This was true for workers currently in part-time employment who would like to find full-time positions and for those who already work full time and would like to increase their hours moderately in order to earn more (Exhibit 17).

In contrast, 17 percent of respondents currently employed would like to reduce their working hours even at the expense of lower earnings, mostly among those in full-time employment who aspire to part-time work. 22 McKinsey Global Institute 1. Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal . Exhibit 17 Many survey respondents currently working would be willing to increase their hours moderately if they were compensated for doing so Maximum willingness to work1 Hours per week Weighted group size >100 90–99 80–89 Readiness to further increase full-time working hours Desire to move into full-time employment 70–79 60–69 50–59 40–49 30–39 Interest in part-time employment 20–29 10–19 <10 <10 10–19 20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 60–69 70–79 Current working hours2 Hours per week 1 Question: On average, how many hours a week do you spend on your work? 2 Question: Imagine you can work as many hours a week as you like and your net income increases accordingly; what is the maximum number of hours you would work in this case? SOURCE: MGI European Aspirations Conjoint Survey, August 2014; McKinsey Global Institute analysis The willingness to work more productively is more difficult to measure precisely than an increase in hours worked. While many productivity-enhancing measures can be nearly invisible to a worker, the commitments made in the conjoint survey refer to improvements that workers could influence directly. These include improved effort, greater ambition at work, and extra training. One piece of evidence corroborating these commitments is the considerable support among respondents for performance-based salaries.

The survey found that 64 percent of respondents believe that salaries in general should reflect performance “more” or “a lot more” than they currently do. Moreover, more than seven out of ten respondents would be prepared to make part or even all of their salary performancebased. Only 16 percent of respondents indicated that they already had a performancebased salary, suggesting that there is significant scope to improve the alignment of incentives with performance in a way that positively resonates with employees. Although the survey findings on working longer and more productively are broadly consistent among respondents, there is considerable disagreement on the degree to which people would want to compromise on social protection.

The survey finds that 84 percent of respondents said that, in their personal optimal scenario, they would be willing to trim their work-life balance in exchange for improvements on other priorities. There is modest variation in the strength of this commitment, according to the survey. However, only 58 percent of respondents expressed a preference for reducing the resources devoted to McKinsey Global Institute A window of opportunity for Europe 23 .

social protection. On this aspect of the survey, there are large differences among countries. For instance, 93 percent of British respondents said that they would accept cuts in social protection, but only 46 percent of those from Poland, 25 percent from Italy, and 24 percent from Spain felt the same way. The average Spanish respondent would like to increase social protection as well as invest more in the other social priorities while making considerable compromises on the work-life balance. In contrast, on average, respondents from France, Sweden, and the United Kingdom say they would be prepared to make relatively small changes to work-life balance and instead opt to cover more than half of the additional resources required through the reallocation of spending on social protection (Exhibit 18). Exhibit 18 The degree to which survey respondents are ready to compromise on social protection varies among countries Relative magnitude of compromises in country-specific average scenarios1 % of total incremental resources required for preferred outcomes Working longer and harder Reallocation away from social protection Increase in social protection spending desired Spain 100 Italy 100 31 69 Germany United Kingdom France 11 89 Romania Sweden 4 96 Poland Decrease in social protection spending desired 35 65 Europe 56 44 41 35 59 65 1 Calculated based on conjoint analysis results and country-specific GDP models. SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis 1/5 of survey respondents would make large compromises on work-life balance for increased social protection 24 A cluster analysis gives us more insight into these differences of opinion on social protection (Exhibit 19).

This analysis reveals five broad groups. Of these, one cluster would like to increase spending on social protection by making even larger compromises in the worklife balance; this group comprises roughly one-fifth of all respondents, more than half of whom are from Spain and Italy. A second cluster, with only 12 percent of respondents, does not favour cuts to social protection but would “pay” for maintaining current protection by forgoing individual income rather than working longer and harder; respondents from Sweden are most prominent in this cluster, accounting for one-third of respondents. The other three clusters all agree that spending on social protection should be reduced significantly, but they differ on the ambition of their aspirations for the other priorities and the extent of their readiness to compromise on their work-life balance.

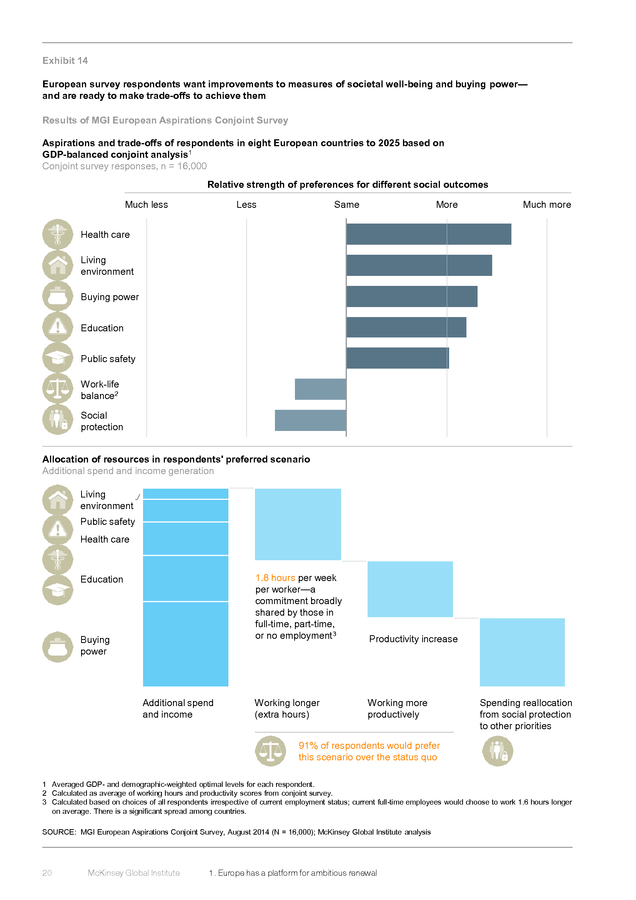

These diverse McKinsey Global Institute 1. Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal . attitudes on social protection come from people of all ages, educational attainment, and employment status. Exhibit 19 The survey results show some variation in attitudes towards social protection spending Desired change from status quo in cluster-specific “average” scenarios1 Cluster I II III IV V Cluster size (%) 25.0 12.3 26.8 21.8 14.1 Characteristic Highest willingness to trade away social protection while preserving worklife balance Low emphasis on buying power, wish to preserve social protection Willing to make moderate compromises for moderate improvements Highest willingness to trade away worklife balance to improve all other priorities including social security Less aspirational on societal priorities, wish to preserve work-life balance Health care Living environment Buying power Education Public safety Work-life balance2 Social protection 1 For cluster-specific average scenarios. 2 Calculated as average of working hours and productivity scores from conjoint survey. SOURCE: MGI European Aspirations Conjoint Survey, August 2014; McKinsey Global Institute analysis There is reason to believe that Europe can grow faster with competitiveness reform and investment and job creation in tandem Current forecasts suggest that there is an expectation that Europe will improve on its postcrisis performance. The average of mid-2014 projections from the Economist Intelligence Unit, IHS, and the Conference Board for real GDP growth between 2013 and 2025 yields a forecast of 1.7 percent per annum—despite the EIU’s projected decline of 0.4 percent in the working-age population. The European Commission takes a slightly more pessimistic view, forecasting growth of 1.5 percent per annum, assuming a slight uptick in annual labour supply growth by 0.1 percent and a productivity-growth boost of 1.4 percent per annum. Europe has an opportunity to grow faster by catching up with best practice. To grasp the potential, consider a scenario in which all countries were to close half of the gap to topquartile European performance on labour productivity and labour-force mobilisation; that is, the share of the working-age population that is active in the labour force) in the period to McKinsey Global Institute A window of opportunity for Europe 25 .

2025. In this scenario, real GDP growth could accelerate to 2.1 percent a year—or more if Europe adopts the kind of growth-enhancing reforms discussed in this report—and real per capita GDP growth to 1.7 percent a year (Exhibit 20). Exhibit 20 Catching up with best practice within Europe could deliver a step change in GDP growth above post-crisis rates and recent forecasts Real GDP Per capita real GDP Comments/assumptions GDP growth per annum, % Catching up with best practice Catching up to top-quartile performance1 Post-crisis GDPgrowth rate 2009–13 performance1 Baseline forecasts 2013–25 2.1 1.7 0.9 0.6 Average external forecasts EU Commission forecast1 Growth rate achieved if: â–ª All countries closed 50% of the gap to top-quartile performance on productivity and labour-force mobilisation to 2025 â–ª Top-quartile productivity performers in 2012 improved productivity at a rate of 1.4% per annum to 2025 â–ª Top-quartile performers on labour-force mobilisation maintained constant mobilisation levels â–ª 1.7 European real GDP performance between 2009 and 2013 â–ª Simple average of forecast 2013–25 from Economist Intelligence Unit, IHS, and Conference Board for Europe-30 â–ª European Commission forecast for EU-27 plus Norway 1.3 1.5 1.2 1 Per capita GDP growth calculated by applying UN population growth forecast. SOURCE: Eurostat; European Commission; United Nations; EIU; IHS; Conference Board; McKinsey Global Growth Model; McKinsey Global Institute analysis While the European economy remains so fragile and GDP growth so weak, a growth rate of 2 percent or above may seem unrealistic. We believe that achieving such a growth rate is possible, although it will require the right institutional enablers. Other advanced economies face demographic challenges similar to Europe’s but are expected to achieve real growth rates of more than 2 percent a year because their productivity is growing strongly.

The US economy, for instance, is expected to grow in real terms at an annual rate of 2.4 percent (1.6 percent per capita) despite modest 0.2 percent projected growth in the working-age population.15 South Korea’s economy is expected to expand by 2.9 percent a year in real terms (2.5 percent per capita) despite an expected contraction of 0.5 percent in its workingage population. To deliver on citizens’ aspirations, European leaders need to work together to develop a comprehensive programme of reform (largely at the national level) and investment and job creation (enabled by pan-European action). Only this combination will overcome inertia and get Europe’s growth engine motoring again (Exhibit 21). GDP growth is based on a simple average of forecasts by the Economist Intelligence Unit, IHS, and Conference Board; population growth is based on a projection from the UN Population Division. 15 26 McKinsey Global Institute 1. Europe has a platform for ambitious renewal .

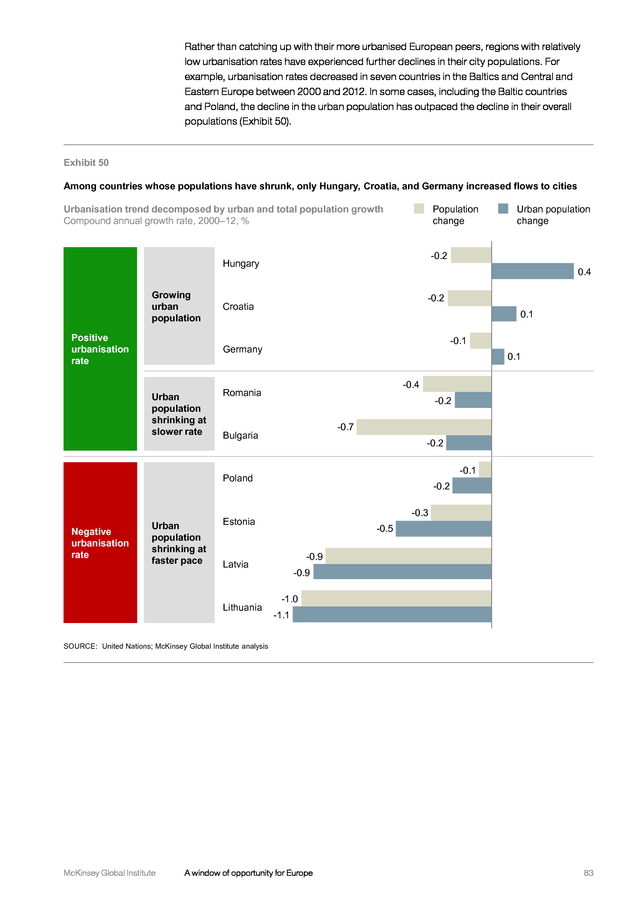

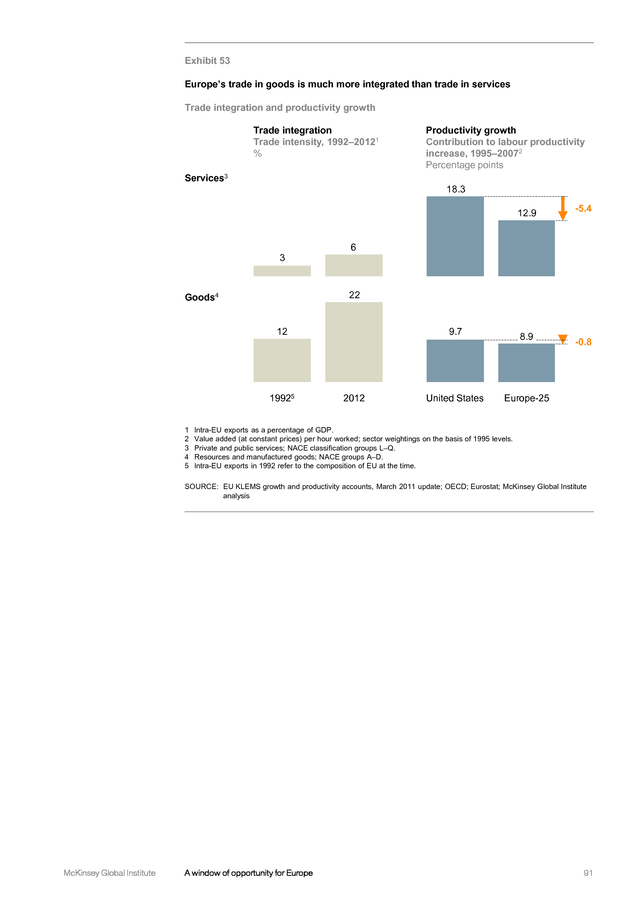

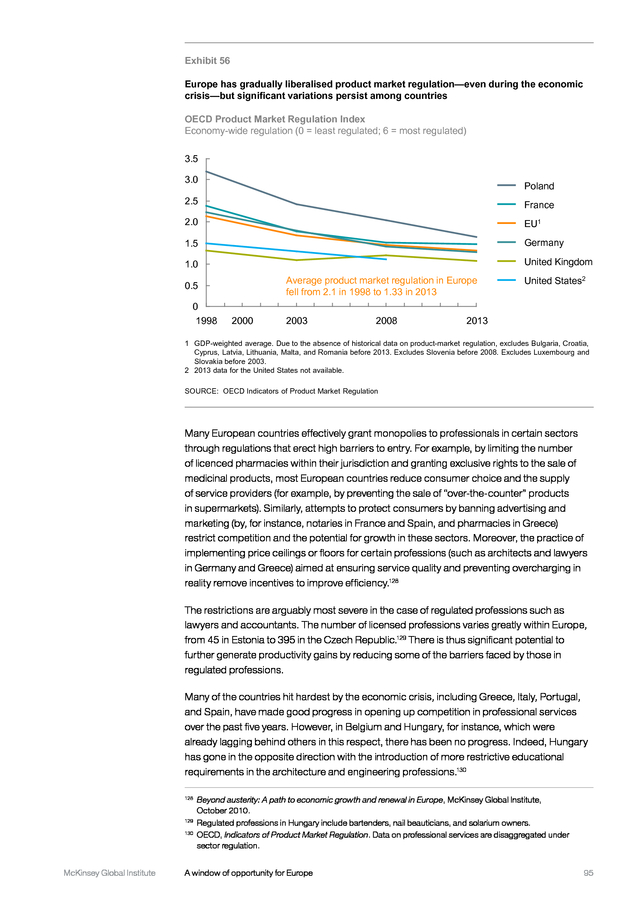

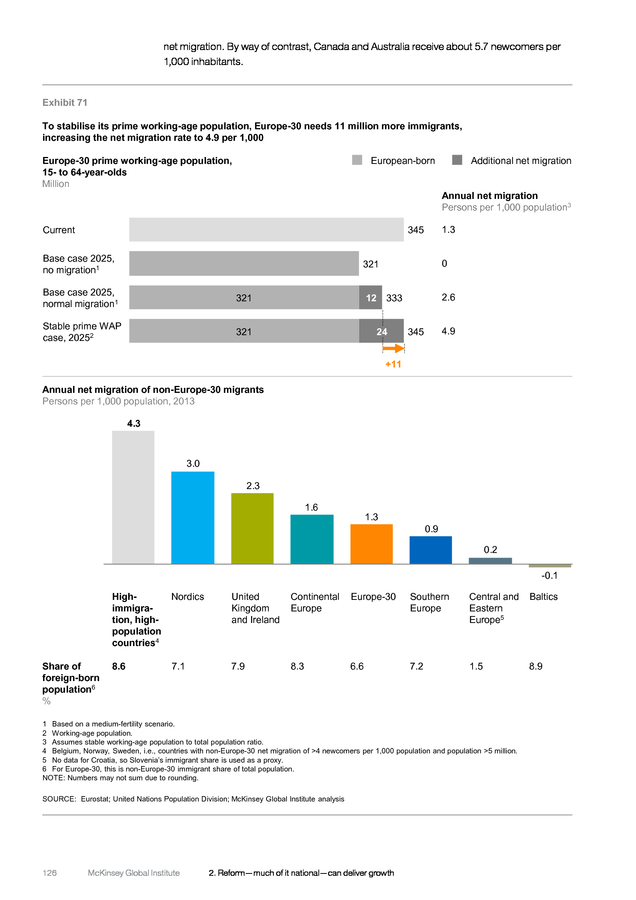

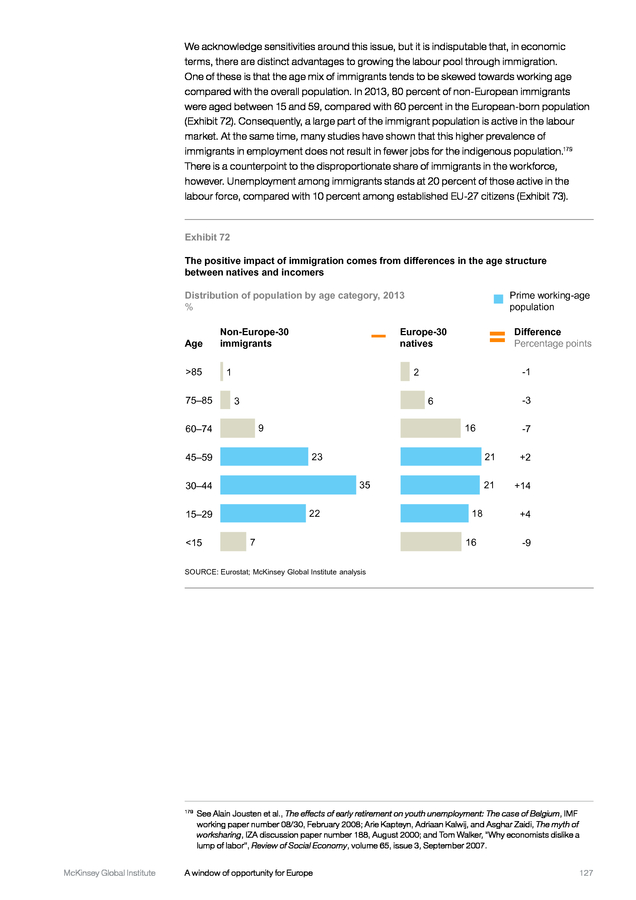

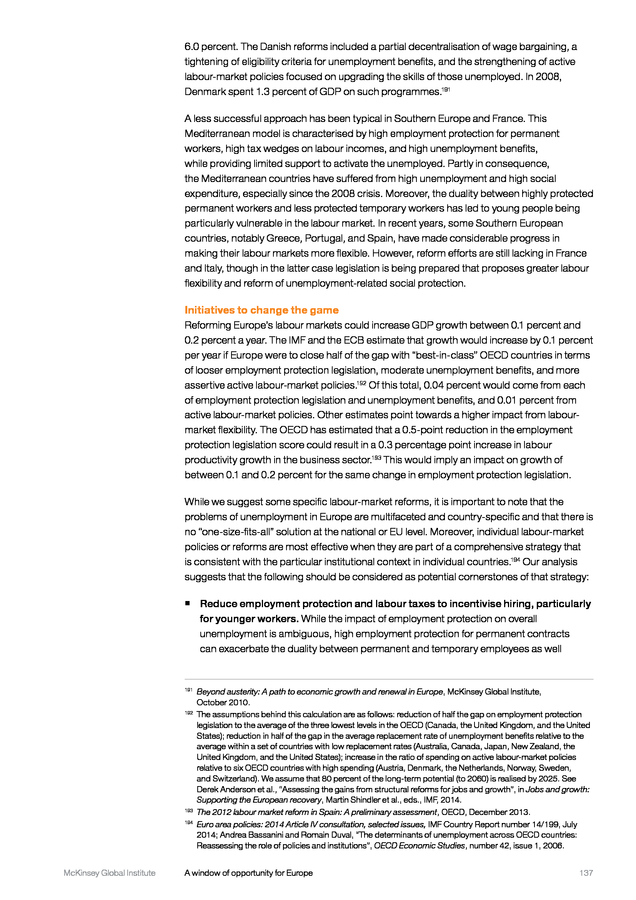

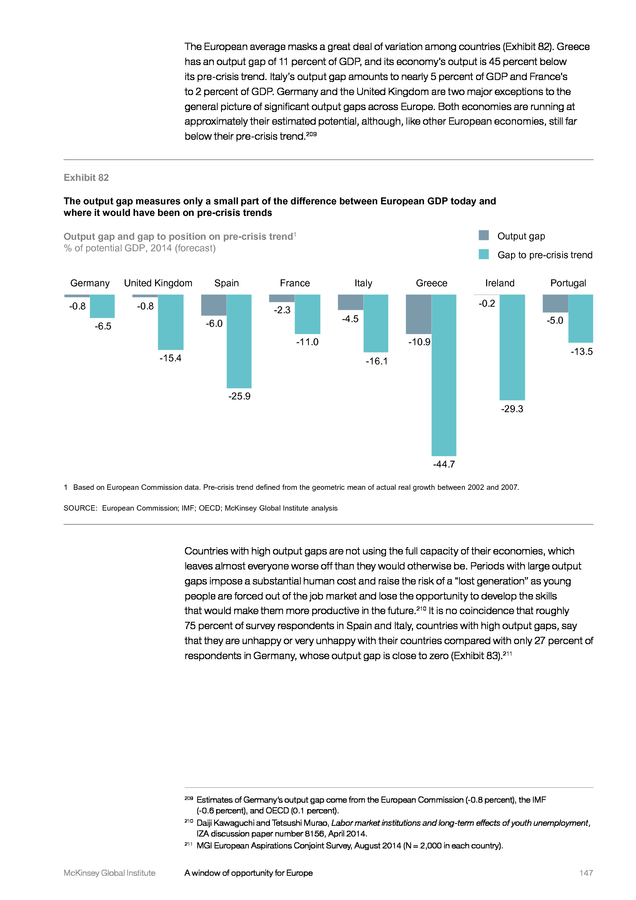

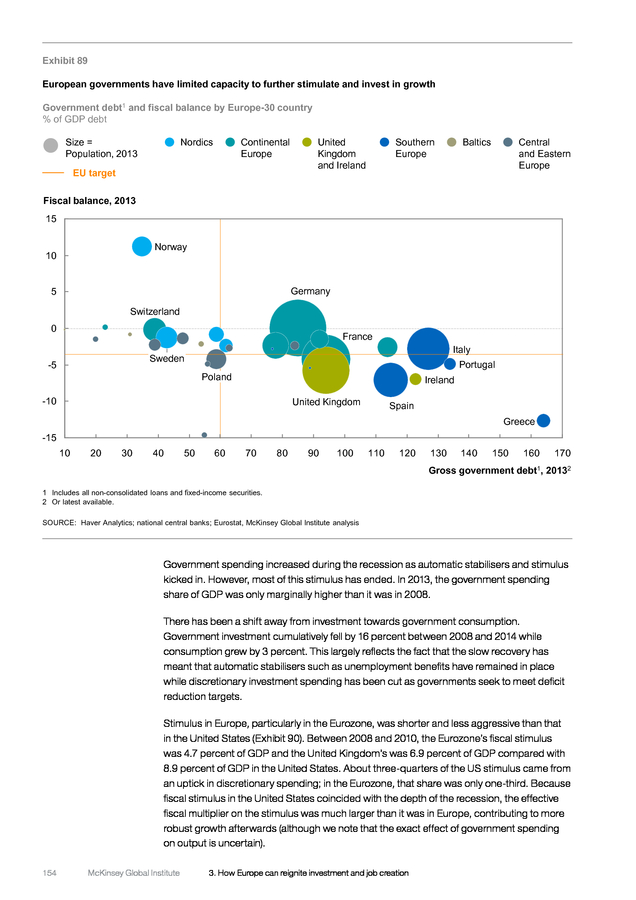

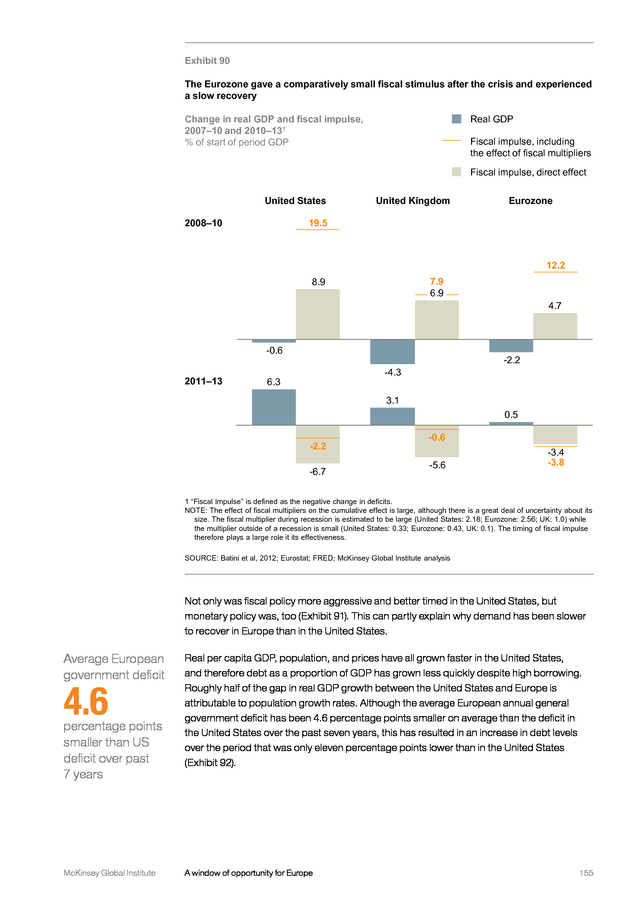

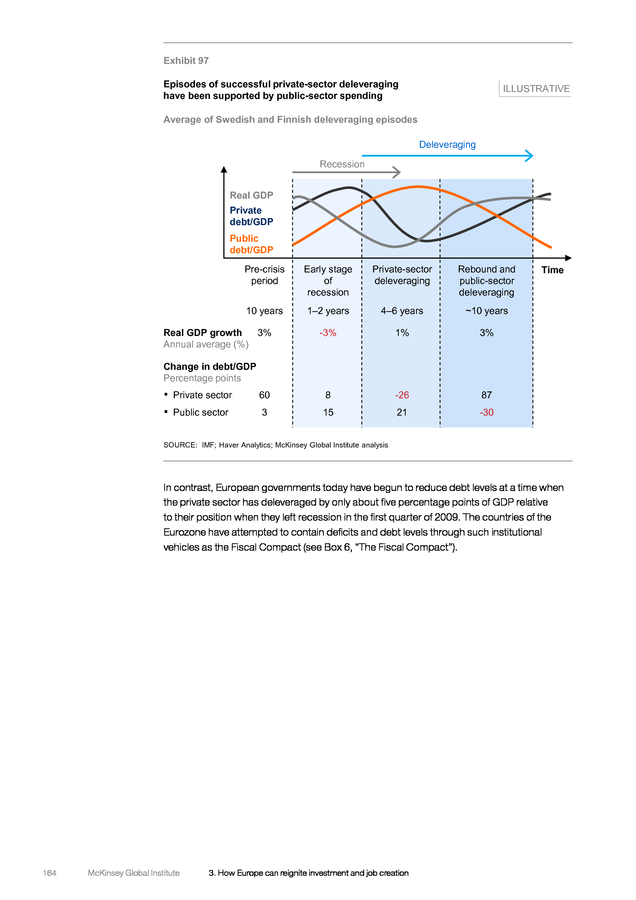

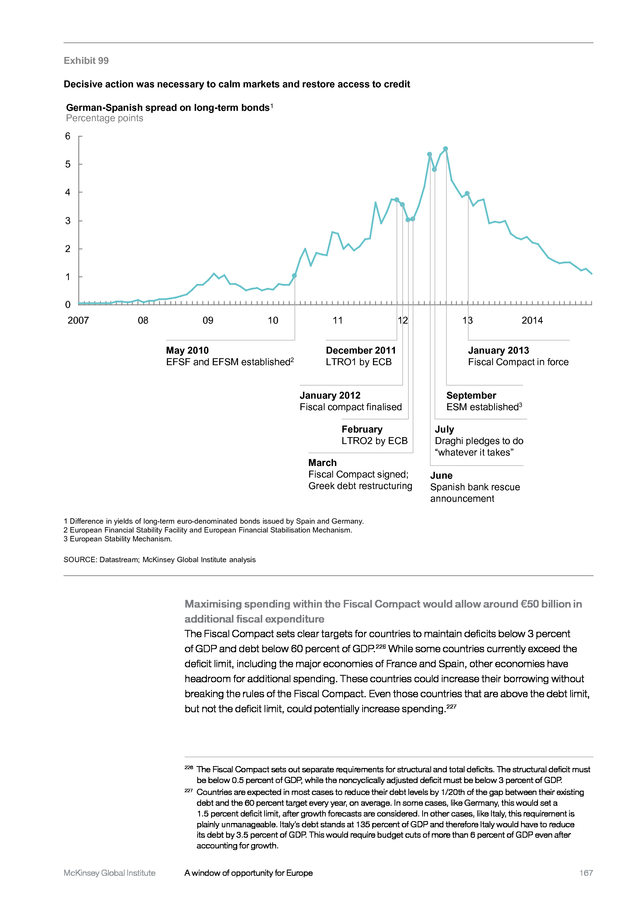

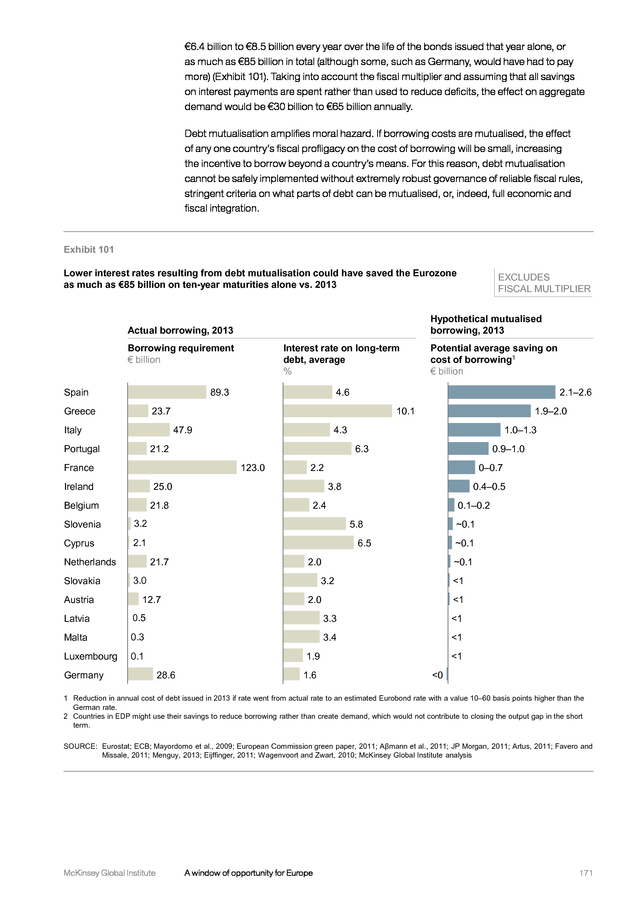

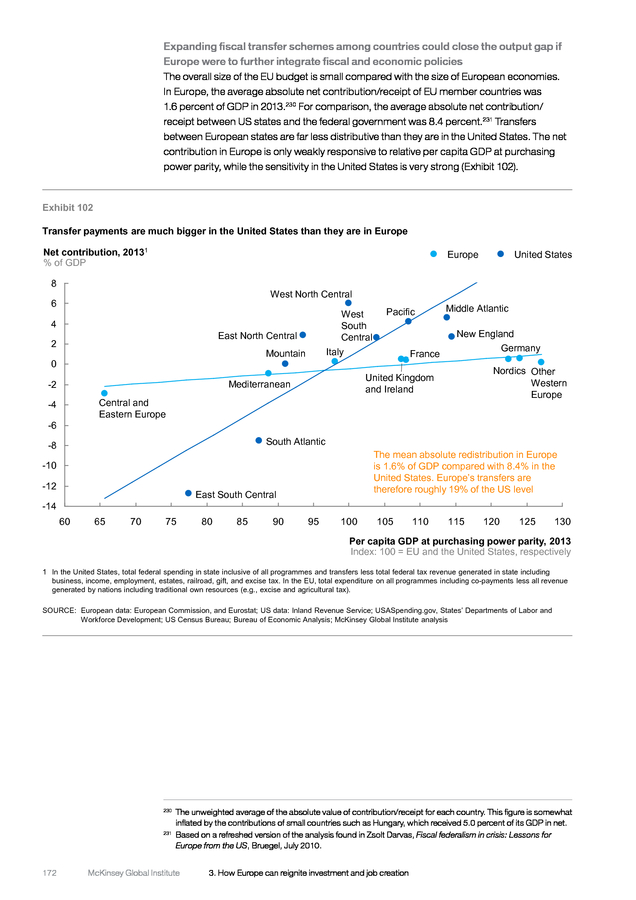

Exhibit 21 Europe will need to work in tandem on reform and support for job creation and investment Reform to boost competitiveness, mostly at national level (75% impact), supported at European level Investment and job creation enabled mostly at the European level SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis ••• There is no guarantee that Europe will achieve the rates of GDP growth that we believe are possible if the region is to embrace reform to boost competitiveness and acts to stimulate investment and job creation. By the same token, these rates are not the upper limits of what can be achieved. Europe has fundamental strengths on which to build, and European citizens express themselves willing to make tough trade-offs to achieve higher growth and incomes. If they are to meet the high aspirations suggested by the MGI survey, Europe’s leaders need to set out a programme that delivers a step change in growth compared with the continent’s recent economic performance and uses the fruits of growth to further strengthen European society and quality of life.