Description

October 2015

Overview of SPACs and Latest

Trends

Joel L. Rubinstein

expenses associated with the IPO—the most significant

component of which is the underwriting discounts and

commissions—the SPAC’s sponsors typically purchase

warrants from the SPAC, for a purchase price equal to their

fair market value, in a private placement that closes

concurrently with the closing of the IPO.

A number of recent successful business combination

transactions involving special-purpose acquisition companies

(SPACs) led by prominent sponsors have driven a resurgence

Until the closing of the IPO, the SPAC cannot hold substantive

in the SPAC IPO market and an evolution in some SPAC

terms. In this article, we provide an overview of SPACs and

discuss the latest trends in SPAC structures and terms.

discussions with a business combination target. Upon the

closing of the IPO, the SPAC’s securities generally are listed

on the Nasdaq Capital Market.

Nasdaq has special listing SPAC Basics requiments for a SPAC, including, among others, that its initial business combination must be with one or more businesses SPACs are blank-check companies formed by sponsors who believe that their experience and reputations will allow them to identify and complete a business combination transaction with a target company that will ultimately be a successful public company. In their initial public offerings (IPOs), SPACs generally offer units, each comprised of one share of common stock and a warrant to purchase common stock. The SPAC’s sponsors typically own 20 percent of the SPAC’s outstanding common stock upon completion of the IPO, comprised of the founder shares they acquired for nominal consideration when they formed the SPAC. An amount equal to 100 percent of the gross proceeds of the IPO raised from public investors is placed into a trust account administered by a third-party trustee.

The IPO proceeds may not be released from the trust account until the closing of the business combination or the redemption of public shares if the SPAC is un-able to complete a business combination within a specified timeframe, as discussed below. In order for the SPAC to be able to pay having an aggregate fair market value of at least 80 percent of the value of the SPAC’s trust account, and that it must complete a business combination within 36 months from the effective date of its IPO registration statement, or such shorter time as specified in its registration statement. Nasdaq listing rules also require that the SPAC have at least 300 round lot shareholders (i.e., holders of at least 100 shares) upon listing, and maintain at least 300 public shareholders after listing. Following the IPO, the SPAC begins to search for a target business.

Under the terms of the SPAC’s organizational documents, if the SPAC is un-able to complete a business combination with a target business within a specified timeframe, typically 24 months from the closing of the IPO, it must return all money in the trust account to the SPAC’s public stockholders, and the founder shares and warrants will be worthless. In addition, at the time of a business combination, the SPAC must prepare and circulate to its shareholders a document containing information concerning the transaction and the target company, including audited Boston Brussels Chicago Dallas Düsseldorf Frankfurt Houston London Los Angeles Miami Milan Munich New York Orange County Paris Rome Seoul Silicon Valley Washington, D.C. Strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices (Shanghai) . INSIDE M&A historical financial statements and pro forma financial the trust account by placing an amount equal to 105 percent or information. This document typically is in the form of a proxy statement, which also is filed with the U.S. Securities and more of the gross proceeds of the offering into the trust account, so that investors whose shares are redeemed receive Exchange Commission (SEC) and is subject to SEC review. Most significantly, at the time of a business combination, each of the SPAC’s public shareholders is given the a return on their investment. This additional cash comes from the investment the sponsors make in the private placement that occurs concurrently with the IPO, which, in this case, is for opportunity to redeem its shares for a pro rata portion of the amount in the trust account, which is generally equal to the amount they paid in the IPO for their units.

If the target shares of common stock, and not warrants. SIZE OF OFFERING AND DUAL CLASS STRUCTURE is affiliated with the SPAC’s sponsors, the SPAC generally is required to obtain a fairness opinion as to the consideration being paid in the transaction. The amount that a SPAC will raise in its IPO is the subject of much discussion when the SPAC is being formed. A general rule of thumb is that the SPAC should raise about one-quarter Once a business combination is completed, the post-closing company continues to be listed on Nasdaq, subject to meeting Nasdaq’s initial listing requirements, or it can apply to list on a different stock exchange. The founder shares are generally locked up for a one-year period following the business combination, often subject to earlier release if the trading price of the company’s stock reaches certain thresholds. Latest Structures and Trends SPAC SECURITIES Most SPACs offer units in their IPO, each comprised of one share and one warrant.

Until recently, most SPAC warrants were exercisable for a full share of common stock. In recent SPACs—depending on the size of the SPAC; the prominence and track record of the sponsors; and the particular investment bank leading the offering—the warrant may be exercisable for a full share of common stock, one-half of one share of common stock or even a one-third of one share of common stock. In any case, the warrants are almost always struck “out of the money,” so that if the per-unit offering price in the IPO is $10, the warrants often have an exercise price of $11.50 per full share.

In addition, the trading price which triggers the company’s right to call the warrants for redemption historically was often $17.50 with a full warrant. Many SPACs that offer less than a full warrant have increased the trading price threshold to $24 to provide additional value. In addition, some SPACs have decided to offer just common stock in their IPOs. In order to compensate investors for the absence of a warrant, the sponsors of such SPACs “overfund” 2 Inside M&A | October 2015 of the expected enterprise value of its business combination target in order to minimize the effect of the dilution resulting from the founder shares and warrants at the time of a business combination. However, it is of course un-certain at the time of the IPO what the enterprise value of the target actually will be given that a target cannot have been identified at the outset. If it turns out that more capital is needed to be raised by the SPAC at the time of the business combination in order to complete the transaction, this may come from the sale by the SPAC of additional equity or equity-linked securities, which would dilute the percentage ownership of the sponsors represented by their founder shares below 20 percent.

In order to maintain that percentage at 20 percent, some SPACs have recently implemented a dual-class structure, in which the founder shares are a separate class of stock that is convertible upon the closing of the business combination into that number of shares of the same class held by the public equal to 20 percent of the outstanding shares after giving effect to the sale of additional equity or equity-linked securities. WARRANT PROTECTION LANGUAGE As noted above, the warrants (including both the public and private placement warrants) represent potential dilution to the shareholders of the post-business combination company. The significance of that potential dilution in any given transaction is generally the subject of discussion between the SPAC and the target, and depends on the number of shares underlying the warrants as compared to the total number of outstanding shares upon completion of the business combination, as well as the terms of the warrant . INSIDE M&A (which are struck “out of the money” and are callable by the company only if the trading price of the stock appreciates meaningfully). In some recent business combination transactions, the SPAC has sought warrantholder approval of a proposal to amend the terms of the warrants so that the warrants are mandatorily exchanged at the closing of the business combination for cash and/or stock, or has conducted a tender offer for the warrants to exchange them for cash and/or stock. As a result of these proposals, which in a number of cases have been successful, some potential investors in newer SPAC IPOs have insisted on including terms that limit the ability of the SPAC to amend the warrants in such a manner unless certain conditions are met. TERM OF THE SPAC Many SPACs historically have had their terms set at a specific number of months (e.g., 18 or 21 months) with an automatic extension for an additional number of months (e.g., an additional three or six months) if the SPAC has entered into a non-binding letter of intent prior to the initial expiration date. Given the relatively low bar of a non-binding letter of intent for an extension, some recent SPACs have eliminated the initial expiration date, and just have a flat 24-month (or more or less) term. REQUIREMENTS FOR REDEMPTIONS Creative Business Combination Structures Allow SPACs to Successfully Compete With Non-SPAC Bidders Heidi J. Steele Certain structural features of special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) that offer benefits to their public investors often put SPACs at a competitive dis-advantage when they are among multiple bidders for a target company.

Recent SPAC business combination transactions demonstrate, however, that careful structuring of a transaction to meet the needs of the target’s owners can overcome these structural challenges and level the playing field for SPACs in a competitive bidding process. SPAC Structure The hallmark feature of the SPAC structure is that the gross proceeds of the SPAC’s initial public offering (IPO) are placed into a trust account for the benefit of the SPAC’s public stockholders. The public stockholders have a right to receive their pro rata share of the trust account if they choose to redeem their common stock in connection with the SPAC’s intial business combination transaction, or if the SPAC is un- In the past, SPACs would require public shareholders to vote against the business combination transaction in order to redeem their shares. In recent SPACs, this requirement has able to complete an initial business combination within a specified period of time, generally 24 months from the closing of the IPO.

The cash in the trust account cannot be accessed been removed, so that a shareholder can redeem even if it votes in favor of the business combination transaction. Some SPACs still require shareholders to vote, either in favor or until the SPAC’s initial business combination is closed. Only a limited amount of additional cash is invested in the SPAC by its sponsors and held outside the trust account to pay the against the transaction, in order to redeem their shares. However, this requirement may make some investors reluctant to purchase shares in the open market after the SPAC’s expenses in connection with identifying, investigating, negotiating and closing its initial business combination transaction. announcement of a business combination transaction and after the record date for the shareholder vote on the transaction, because they would not obtain the ability to vote and, hence, redeem their shares. The Appeal of SPACs For the SPAC’s public investors, the trust account structure is intended to eliminate the downside risk of their investment.

If the SPAC fails to complete a business combination transaction within the specified time period, or if an investor redeems its shares in connection with the SPAC’s initial business combination transaction, the investor receives substantially all of its initial investment back. For target companies, a SPAC’s Inside M&A | October 2015 3 . INSIDE M&A public company status allows them to go public more quickly than the timing of a traditional public offering. It also provides a path to go public for companies whose stories may not be appreciated by public market investors. Perhaps more significantly, a business combination transaction with a SPAC provides a significant amount of flexibility for the target’s owners to receive a portion of their business combination consideration in cash and a portion in public company stock, which will allow them to participate in the future growth of the business. The SPAC Challenges While the SPAC structure provides public investors with safeguards to protect their investment, it also creates obstacles to closing a business combination. The redemption rights of SPAC stockholders and the short SPAC lifespan can SPAC Solutions Recently completed SPAC business combinations demonstrate how SPACs can be successfully utilized in the private equity dominated mergers-and-acquisitions (M&A) market.

To compete with private equity bidders’ access to cash, SPACs can enter into arrangements with third-party investors or the SPAC’s sponsors to “backstop” a specified amount of potential redemptions by public stockholders at the same price per share as the redemption price per share. These arrangements can guarantee cash certainty at closing and provide validation of the SPAC’s valuation of the business combination transaction, which in turn supports the trading price of the SPAC’s shares. These arrangements encourage targets to be more accepting of the timing and public disclosure requirements and the redemption process of SPAC bidders. create deal un-certainty and timing obstacles, making targets reluctant to sell to a SPAC. Targets often want at least some cash consideration or for a specified amount of cash to remain In addition, the attenuated timing to closing inherent in SPAC transactions for sellers who are seeking cash can be in the company for future growth—and always desire certainty of closing—but the ability of the SPAC stockholders to redeem addressed through these arrangements.

For example, the recent $500 million acquisition of Del Taco Holdings, Inc. by their shares can impact both. Even if SPAC business combination agreements include a minimum cash condition to protect a target from a closing if more redemptions than Levy Acquisition Corp.

included a novel two-step structure. In the first step, the SPAC’s sponsor and third-party investors made an upfront cash investment of $120 million in the equity expected occur, a SPAC generally cannot offer the deal protection of a breakup fee due to its lack of access to the trust account funds prior to closing a business combination. of Del Taco by purchasing stock from Del Taco stockholders and the company itself. The upfront investment provided stockholders with immediate liquidity for a portion of their Further, a large number of redemptions can put the post business combination’s public company status at risk due to a reduced market float that does not meet public company listing requirements.

The time it takes to close a SPAC business combination adds to these impediments, putting a SPAC at a dis-advantage against private equity funds and strategic buyers in a competitive bidding process. In a SPAC business combination transaction, the parties must file disclosure documents with the U.S. Securities and Exchange holdings and allowed Del Taco to re-finance its indebtedness—making its debt/equity ratio a more suitable investment for public investors.

In addition, at the time of entering into the agreement for the business combination transaction, the SPAC arranged for a $35 million private placement to take place at the closing of the business combination to provide additional cash and additional deal certainty. Moreover, because the price paid in both the step-one cash Commission (SEC), which include extensive information about the transaction and the target, including audited financial statements, pro forma financial information and other investment and the closing private placement was based on the proposed $500 million enterprise value for Del Taco in the business combination transaction, it demonstrated to the information that is typically disclosed in an IPO prospectus. The process of preparing and resolving SEC comments on these documents is time-consuming and expensive. Unless market and SPAC stockholders that third-party investors and the SPAC’s sponsor supported the proposed valuation of the transaction. The additional cash investments also helped these obstacles are addressed, some sellers may discount the bid of a SPAC and not enter into a sale process with a SPAC. support a SPAC common stock price at or in excess of the redemption price that SPAC stockholders would receive if they 4 Inside M&A | October 2015 .

INSIDE M&A redeemed their shares. The transaction was well-received by the public markets, with the SPAC’s common stock trading up to more than $5 above the per-share trust amount prior to the closing of the business combination transaction, resulting in nominal redemptions by public stockholders. SPAC Directors Cannot Take the Protection of the Business Judgment Rule for Granted Michael J. Dillon In Boulevard Acquisition Corp.’s recent acquisition of AgroFresh, a business of The Dow Chemical Company, more than two-thirds of the purchase price was paid with cash infused in the business combination in the form of a private placement completed concurrently with the closing, increased debt on the target and standby agreement under which the seller and an affiliate of sponsor agreement to provide up to $50 million in the event that the SPAC had insufficient cash to pay the full cash consideration. Similar to the Del Taco transaction, a significant portion of the cash infusion came from parties to the business combination, an affiliate of the sponsor and The Dow Chemical Company, which served as an endorsement of the business combination valuation to the market.

The AgroFresh transaction demonstrates how a business combination with a SPAC can be an alternative to the traditional spin-off transaction. These recent SPAC transactions demonstrate that SPACs can significantly increase deal certainty and their competitive position in bidding processes by utilizing one or more of the following:  An upfront cash investment to provide owners of the target immediate cash liquidity and validation that the equity value of the SPAC post-business combination is greater than the redemption price (thus discouraging redemptions)  Re-financing the post-business combination company to make it in line with debt/equity leverage ratios of public companies of similarly situated businesses  Obtaining additional support by means of a capital infusion or continued investment in the company by the sellers and/or sponsor to show confidence in the valuation of the business combination The strategic decisions made by directors of Delaware corporations are typically accorded the protection of the business judgment rule, which “is a presumption that in making a business decision, the directors of a corporation acted on an informed basis, in good faith and in the honest belief that the action taken was in the best interests of the company.” (Aronson v. Lewis, 473 A.2d 805 (Del. 1984)).

This presumption may be rebutted if, among other things, it is shown that the directors had a conflict of interest in making the decision or breached their fiduciary duties, in which case the burden shifts to the directors to defend the decision under the entire fairness standard. A recent decision by the New York State Supreme Court’s Commercial Division—in AP Services, LLP v. Lobell, et al., No.

651613/12—suggests that certain structural terms of special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) may make it more challenging for the business judgment rule to apply to decisions by SPAC directors to enter into agreements for business combination transactions. Background In June 2005, principals of a bioscience venture capital firm founded Paramount Acquisition Corp. (Paramount) as a SPAC, purchasing 2,125,000 shares of Paramount’s common stock (founder shares) for $0.01176 per share, or $25,000 in the aggregate. These principals also served as members of the board of directors of Paramount.

In October 2005, Paramount conducted its initial public offering (IPO), selling 9,775,000 units, each consisting of one share of common stock and two warrants, for a purchase price of $6 per unit, raising approximately $53 million in net proceeds after offering expenses. Approximately $52 million of the proceeds was placed into a trust account for the benefit of Paramount’s public stockholders. Following the IPO, pursuant to an agreement with the underwriters of the IPO, Paramount’s directors purchased approximately two million warrants in the open market for an aggregate purchase price of approximately $1.3 million. Inside M&A | October 2015 5 .

INSIDE M&A According to the IPO prospectus, Paramount’s purpose was to entered into forbearance agreements with its lenders and, effect a business combination transaction with an operating business in the health care industry. However, under according to the complaint in Lobell, the company admitted that the historical audited financial statements on which the Paramount’s certificate of incorporation, if a shareholderapproved acquisition of a health care entity failed to close by a “drop-dead” date [either April 27, 2007 (18 months after Business Combination Transaction was based were false. In violation of its loan covenants, and un-able to work out its debt, Chem Rx filed for bankruptcy in May 2010. The Paramount’s IPO) or October 27, 2007 (24 months after Paramount’s IPO) if Paramount had entered into a letter of intent by April 27, 2007, but the transaction had not closed by bankruptcy led to a distressed sale of Chem Rx and a Chapter 11 liquidation.

Following liquidation, the bankruptcy court established a litigation trust to prosecute claims for Chem Rx’s such date], Paramount would dissolve. In such an event, the IPO proceeds held in the trust account would be distributed in liquidation to Paramount’s public stockholders, and all of un-secured creditors. Paramount’s warrants (including those purchased by the directors) would expire worthless. In connection with the IPO, the directors waived their right to any liquidating distributions from the trust account with respect to their founder shares.

In addition, under the terms of Paramount’s certificate of incorporation, public stockholders would have the right to convert their public shares into a pro rata portion of the proceeds held in the trust account in connection with a business combination transaction if they voted against the Lobell is the litigation trust’s (i.e., the Plaintiff’s) suit against Paramount’s directors (the Directors), in which the Plaintiff alleged, inter alia, that the Directors breached their fiduciary duties of loyalty and care to Paramount by allowing Paramount to enter into the Business Combination Transaction, because, in approving the transaction, the Directors were self-interested or controlled by an interested director and, in their rush to approve the Business Combination Transaction, the Directors transaction. ignored key red flags that should have alerted them to the fact that Chem Rx's audited financial statements were untrustworthy. The Directors moved to dismiss Plaintiff’s On April 24, 2007, after having considered a number of business combination candidates, and after a different complaint, arguing, among other things, that their decision to approve the Business Combination Transaction should be protected by Delaware’s business judgment rule. potential transaction fell through, Paramount entered into a letter of intent for a business combination with Chem Rx, a long-term-care pharmacy, as well as letters of intent for two other potential business combinations, thereby extending the drop-dead date to October. On October 22, 2007, five days before the drop-dead date, Paramount acquired Chem Rx in a leveraged acquisition in which it used the cash remaining in its trust account after conversions plus approximately $160 million in debt financing and 2.5 million shares as the purchase price (the Business Combination Transaction).

In connection with the closing of the transaction, Paramount changed its Justice Marcy Friedman ruled on the motion in a June 19, 2015, decision/order (the Lobell Order), dismissing certain causes of action but denying the Directors’ motion with regard to the fiduciary breach claim. Specifically, the court rejected the Directors’ reliance on the business judgment rule in their argument for dismissal, holding that the Plaintiff alleged sufficient facts to plead a claim for breach of the duty of loyalty or a claim for breach of the duty of due care. An appeal of the Lobell Order filed by both parties remains pending in the First Department. name to Chem Rx Corporation. Analysis In April 2009, 18 months after the transaction closed, Chem Rx publicly announced that it was un-able to file its annual report for 2008, because it was in violation of certain financial covenants under its two principal credit facilities and, because of the un-certainty as to a resolution of the covenant violations, the proper accounting for the credit facility indebtedness was in doubt.

In May 2009, Chem Rx announced that it had 6 Inside M&A | October 2015 The court’s conclusion that the Plaintiff adequately pled a breach of the duty of loyalty was based on the alleged selfinterest of the majority of the Directors arising from their ownership of founder shares and warrants, which would have no value if Paramount did not close the Business Combination Transaction by the drop-dead date. This has implications for . INSIDE M&A many SPACs, because it is common for SPAC directors to flags, and that their failure to investigate in response to the red own similar founder shares or warrants. flags amounts to “gross negligence” and “intentional dereliction of their fiduciary duties.” The court acknowledged these One of the arguments the Directors made in their defense was allegations, and found that even where the SPAC’s certificate of incorporation exculpates the directors from ordinary negligence, a duty-of-care claim may be premised on gross that the Directors did not have the power to cause the acquisition to be made, because it was expressly subject to the affirmative vote of a supermajority of dis-interested stockholders. In its decision, the court acknowledged this argument in a footnote, but stated that the Defendants did not submit “legal authority addressing the impact on directors’ good faith decision-making of investor protections which may be adopted in connection with SPACS, including a requirement that a majority of IPO stockholders approve a business combination” and that the court expected this omission to be “addressed at a future stage of the litigation.” Notably, there are numerous Delaware court decisions holding that the legal effect of a fully informed stockholder vote of a transaction is that the business judgment rule applies and insulates the transaction from all attacks other than on the grounds of waste, even if a majority of the board approving the transaction was not dis-interested or independent. See In re KKR Financial Holdings LLC Shareholder Litigation, C.A. No. 9210-CB (Del.

Ch. October 14, 2014). Thus, this defense should ultimately prevail if the Defendants can show that the disclosure included by Paramount in its proxy statement for the stockholder vote was sufficient to fully inform Paramount’s stockholders about the Business Combination Transaction, as well as that it did not constitute waste, which is a low bar to meet. In a related argument, the Defendants asserted that the ability of each public stockholder to choose to convert their shares into a pro rata portion of the trust account also supported the notion that the board decision had no operative effect and, therefore, that it could not constitute a breach of fiduciary duty.

Here, too, the Defendants did not cite legal authority, which they may seek to do in a future stage of the litigation. However, neither of these arguments was dispositive of the motion before the court, as the court’s focus was solely on the sufficiency of the pleading. Thus, the court’s conclusion that the Plaintiff adequately pled a breach of the duty of care puts a focus on the adequacy of the due diligence that SPACs undertake in connection with their business combination transactions. The Plaintiff claimed that negligence in failing to heed red flags. Key Takeaways The Lobell Order highlights the need for SPAC directors to make sure that management of the SPAC engages in thorough due diligence of a business combination target, and investigates any red flags before entering into a binding agreement to fulfill their duty of care.

Directors also should ensure that the disclosure document that the SPAC prepares and circulates to its shareholders is comprehensive and highlights not only the positive aspects of the target, but also any negatives. Thus, the shareholders can make an informed decision, and approve the transaction by a majority of disinterested shareholders (as a supermajority vote of public stockholders no longer is required under SPAC charters in order to approve a business combination). By taking these two steps—even if the directors own founder shares or warrants— their decisions may qualify for the protection of the business judgment rule.

SPACs may also consider appointing one or more directors who do not own any founder shares or warrants—and are not otherwise affiliated with the principal sponsor—to act as a special independent committee to approve the transaction, thereby obviating the need to rely on an informed decision by shareholders in order to qualify for the protection of the business judgment rule. McDERMOTT CORPORATE HIGHLIGHTS McDermott Expands in Dallas’ Uptown District to Accommodate Growing Practice Our recently opened Dallas office has relocated to more expansive space in the Uptown business district. Over the past six months, the office has added almost two dozen corporate, tax controversy, technology and outsourcing lawyers. the Directors "willfully ignored" and "closed their eyes" to red Inside M&A | October 2015 7 . INSIDE M&A EDITORS For more information, please contact your regular McDermott lawyer, or: Jake Townsend +1 312 984 3673 jtownsend@mwe.com Joel L. Rubinstein +1 212 547 5336 jrubinstein@mwe.com For more information about McDermott Will & Emery visit www.mwe.com IRS Circular 230 Disclosure: To comply with requirements imposed by the IRS, we inform you that any U.S. federal tax advice contained herein (including any attachments), unless specifically stated otherwise, is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for the purposes of (i) avoiding penalties under the Internal Revenue Code or (ii) promoting, marketing or recommending to another party any transaction or matter herein. The material in this publication may not be reproduced, in whole or part without acknowledgement of its source and copyright. Inside M&A is intended to provide information of general interest in a summary manner and should not be construed as individual legal advice.

Readers should consult with their McDermott Will & Emery lawyer or other professional counsel before acting on the information contained in this publication. ©2015 McDermott Will & Emery. The following legal entities are collectively referred to as “McDermott Will & Emery,” “McDermott” or “the Firm”: McDermott Will & Emery LLP, McDermott Will & Emery AARPI, McDermott Will & Emery Belgium LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Rechtsanwälte Steuerberater LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Studio Legale Associato and McDermott Will & Emery UK LLP. These entities coordinate their activities through service agreements.

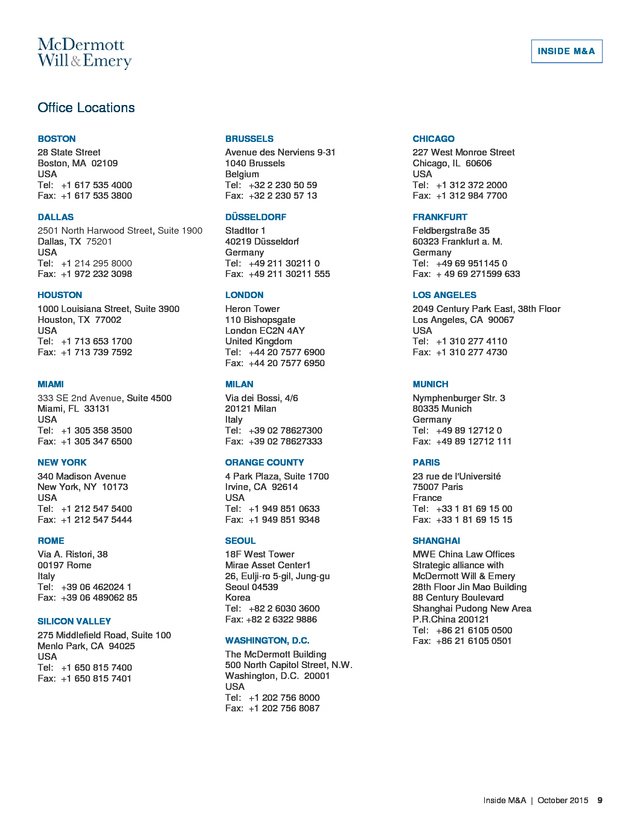

McDermott has a strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices, a separate law firm. This communication may be considered attorney advertising. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. 8 Inside M&A | October 2015 . INSIDE M&A Office Locations BOSTON BRUSSELS CHICAGO 28 State Street Boston, MA 02109 USA Tel: +1 617 535 4000 Fax: +1 617 535 3800 Avenue des Nerviens 9-31 1040 Brussels Belgium Tel: +32 2 230 50 59 Fax: +32 2 230 57 13 227 West Monroe Street Chicago, IL 60606 USA Tel: +1 312 372 2000 Fax: +1 312 984 7700 DALLAS DÜSSELDORF FRANKFURT 2501 North Harwood Street, Suite 1900 Dallas, TX 75201 USA Tel: +1 214 295 8000 Fax: +1 972 232 3098 Stadttor 1 40219 Düsseldorf Germany Tel: +49 211 30211 0 Fax: +49 211 30211 555 Feldbergstraße 35 60323 Frankfurt a. M. Germany Tel: +49 69 951145 0 Fax: + 49 69 271599 633 HOUSTON LONDON LOS ANGELES 1000 Louisiana Street, Suite 3900 Houston, TX 77002 USA Tel: +1 713 653 1700 Fax: +1 713 739 7592 Heron Tower 110 Bishopsgate London EC2N 4AY United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7577 6900 Fax: +44 20 7577 6950 2049 Century Park East, 38th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90067 USA Tel: +1 310 277 4110 Fax: +1 310 277 4730 MIAMI MILAN MUNICH 333 SE 2nd Avenue, Suite 4500 Miami, FL 33131 USA Tel: +1 305 358 3500 Fax: +1 305 347 6500 Via dei Bossi, 4/6 20121 Milan Italy Tel: +39 02 78627300 Fax: +39 02 78627333 Nymphenburger Str. 3 80335 Munich Germany Tel: +49 89 12712 0 Fax: +49 89 12712 111 NEW YORK ORANGE COUNTY PARIS 340 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10173 USA Tel: +1 212 547 5400 Fax: +1 212 547 5444 4 Park Plaza, Suite 1700 Irvine, CA 92614 USA Tel: +1 949 851 0633 Fax: +1 949 851 9348 23 rue de l'Université 75007 Paris France Tel: +33 1 81 69 15 00 Fax: +33 1 81 69 15 15 ROME SEOUL SHANGHAI Via A. Ristori, 38 00197 Rome Italy Tel: +39 06 462024 1 Fax: +39 06 489062 85 18F West Tower Mirae Asset Center1 26, Eulji-ro 5-gil, Jung-gu Seoul 04539 Korea Tel: +82 2 6030 3600 Fax: +82 2 6322 9886 MWE China Law Offices Strategic alliance with McDermott Will & Emery 28th Floor Jin Mao Building 88 Century Boulevard Shanghai Pudong New Area P.R.China 200121 Tel: +86 21 6105 0500 Fax: +86 21 6105 0501 SILICON VALLEY 275 Middlefield Road, Suite 100 Menlo Park, CA 94025 USA Tel: +1 650 815 7400 Fax: +1 650 815 7401 WASHINGTON, D.C. The McDermott Building 500 North Capitol Street, N.W. Washington, D.C.

20001 USA Tel: +1 202 756 8000 Fax: +1 202 756 8087 Inside M&A | October 2015 9 .

Nasdaq has special listing SPAC Basics requiments for a SPAC, including, among others, that its initial business combination must be with one or more businesses SPACs are blank-check companies formed by sponsors who believe that their experience and reputations will allow them to identify and complete a business combination transaction with a target company that will ultimately be a successful public company. In their initial public offerings (IPOs), SPACs generally offer units, each comprised of one share of common stock and a warrant to purchase common stock. The SPAC’s sponsors typically own 20 percent of the SPAC’s outstanding common stock upon completion of the IPO, comprised of the founder shares they acquired for nominal consideration when they formed the SPAC. An amount equal to 100 percent of the gross proceeds of the IPO raised from public investors is placed into a trust account administered by a third-party trustee.

The IPO proceeds may not be released from the trust account until the closing of the business combination or the redemption of public shares if the SPAC is un-able to complete a business combination within a specified timeframe, as discussed below. In order for the SPAC to be able to pay having an aggregate fair market value of at least 80 percent of the value of the SPAC’s trust account, and that it must complete a business combination within 36 months from the effective date of its IPO registration statement, or such shorter time as specified in its registration statement. Nasdaq listing rules also require that the SPAC have at least 300 round lot shareholders (i.e., holders of at least 100 shares) upon listing, and maintain at least 300 public shareholders after listing. Following the IPO, the SPAC begins to search for a target business.

Under the terms of the SPAC’s organizational documents, if the SPAC is un-able to complete a business combination with a target business within a specified timeframe, typically 24 months from the closing of the IPO, it must return all money in the trust account to the SPAC’s public stockholders, and the founder shares and warrants will be worthless. In addition, at the time of a business combination, the SPAC must prepare and circulate to its shareholders a document containing information concerning the transaction and the target company, including audited Boston Brussels Chicago Dallas Düsseldorf Frankfurt Houston London Los Angeles Miami Milan Munich New York Orange County Paris Rome Seoul Silicon Valley Washington, D.C. Strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices (Shanghai) . INSIDE M&A historical financial statements and pro forma financial the trust account by placing an amount equal to 105 percent or information. This document typically is in the form of a proxy statement, which also is filed with the U.S. Securities and more of the gross proceeds of the offering into the trust account, so that investors whose shares are redeemed receive Exchange Commission (SEC) and is subject to SEC review. Most significantly, at the time of a business combination, each of the SPAC’s public shareholders is given the a return on their investment. This additional cash comes from the investment the sponsors make in the private placement that occurs concurrently with the IPO, which, in this case, is for opportunity to redeem its shares for a pro rata portion of the amount in the trust account, which is generally equal to the amount they paid in the IPO for their units.

If the target shares of common stock, and not warrants. SIZE OF OFFERING AND DUAL CLASS STRUCTURE is affiliated with the SPAC’s sponsors, the SPAC generally is required to obtain a fairness opinion as to the consideration being paid in the transaction. The amount that a SPAC will raise in its IPO is the subject of much discussion when the SPAC is being formed. A general rule of thumb is that the SPAC should raise about one-quarter Once a business combination is completed, the post-closing company continues to be listed on Nasdaq, subject to meeting Nasdaq’s initial listing requirements, or it can apply to list on a different stock exchange. The founder shares are generally locked up for a one-year period following the business combination, often subject to earlier release if the trading price of the company’s stock reaches certain thresholds. Latest Structures and Trends SPAC SECURITIES Most SPACs offer units in their IPO, each comprised of one share and one warrant.

Until recently, most SPAC warrants were exercisable for a full share of common stock. In recent SPACs—depending on the size of the SPAC; the prominence and track record of the sponsors; and the particular investment bank leading the offering—the warrant may be exercisable for a full share of common stock, one-half of one share of common stock or even a one-third of one share of common stock. In any case, the warrants are almost always struck “out of the money,” so that if the per-unit offering price in the IPO is $10, the warrants often have an exercise price of $11.50 per full share.

In addition, the trading price which triggers the company’s right to call the warrants for redemption historically was often $17.50 with a full warrant. Many SPACs that offer less than a full warrant have increased the trading price threshold to $24 to provide additional value. In addition, some SPACs have decided to offer just common stock in their IPOs. In order to compensate investors for the absence of a warrant, the sponsors of such SPACs “overfund” 2 Inside M&A | October 2015 of the expected enterprise value of its business combination target in order to minimize the effect of the dilution resulting from the founder shares and warrants at the time of a business combination. However, it is of course un-certain at the time of the IPO what the enterprise value of the target actually will be given that a target cannot have been identified at the outset. If it turns out that more capital is needed to be raised by the SPAC at the time of the business combination in order to complete the transaction, this may come from the sale by the SPAC of additional equity or equity-linked securities, which would dilute the percentage ownership of the sponsors represented by their founder shares below 20 percent.

In order to maintain that percentage at 20 percent, some SPACs have recently implemented a dual-class structure, in which the founder shares are a separate class of stock that is convertible upon the closing of the business combination into that number of shares of the same class held by the public equal to 20 percent of the outstanding shares after giving effect to the sale of additional equity or equity-linked securities. WARRANT PROTECTION LANGUAGE As noted above, the warrants (including both the public and private placement warrants) represent potential dilution to the shareholders of the post-business combination company. The significance of that potential dilution in any given transaction is generally the subject of discussion between the SPAC and the target, and depends on the number of shares underlying the warrants as compared to the total number of outstanding shares upon completion of the business combination, as well as the terms of the warrant . INSIDE M&A (which are struck “out of the money” and are callable by the company only if the trading price of the stock appreciates meaningfully). In some recent business combination transactions, the SPAC has sought warrantholder approval of a proposal to amend the terms of the warrants so that the warrants are mandatorily exchanged at the closing of the business combination for cash and/or stock, or has conducted a tender offer for the warrants to exchange them for cash and/or stock. As a result of these proposals, which in a number of cases have been successful, some potential investors in newer SPAC IPOs have insisted on including terms that limit the ability of the SPAC to amend the warrants in such a manner unless certain conditions are met. TERM OF THE SPAC Many SPACs historically have had their terms set at a specific number of months (e.g., 18 or 21 months) with an automatic extension for an additional number of months (e.g., an additional three or six months) if the SPAC has entered into a non-binding letter of intent prior to the initial expiration date. Given the relatively low bar of a non-binding letter of intent for an extension, some recent SPACs have eliminated the initial expiration date, and just have a flat 24-month (or more or less) term. REQUIREMENTS FOR REDEMPTIONS Creative Business Combination Structures Allow SPACs to Successfully Compete With Non-SPAC Bidders Heidi J. Steele Certain structural features of special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) that offer benefits to their public investors often put SPACs at a competitive dis-advantage when they are among multiple bidders for a target company.

Recent SPAC business combination transactions demonstrate, however, that careful structuring of a transaction to meet the needs of the target’s owners can overcome these structural challenges and level the playing field for SPACs in a competitive bidding process. SPAC Structure The hallmark feature of the SPAC structure is that the gross proceeds of the SPAC’s initial public offering (IPO) are placed into a trust account for the benefit of the SPAC’s public stockholders. The public stockholders have a right to receive their pro rata share of the trust account if they choose to redeem their common stock in connection with the SPAC’s intial business combination transaction, or if the SPAC is un- In the past, SPACs would require public shareholders to vote against the business combination transaction in order to redeem their shares. In recent SPACs, this requirement has able to complete an initial business combination within a specified period of time, generally 24 months from the closing of the IPO.

The cash in the trust account cannot be accessed been removed, so that a shareholder can redeem even if it votes in favor of the business combination transaction. Some SPACs still require shareholders to vote, either in favor or until the SPAC’s initial business combination is closed. Only a limited amount of additional cash is invested in the SPAC by its sponsors and held outside the trust account to pay the against the transaction, in order to redeem their shares. However, this requirement may make some investors reluctant to purchase shares in the open market after the SPAC’s expenses in connection with identifying, investigating, negotiating and closing its initial business combination transaction. announcement of a business combination transaction and after the record date for the shareholder vote on the transaction, because they would not obtain the ability to vote and, hence, redeem their shares. The Appeal of SPACs For the SPAC’s public investors, the trust account structure is intended to eliminate the downside risk of their investment.

If the SPAC fails to complete a business combination transaction within the specified time period, or if an investor redeems its shares in connection with the SPAC’s initial business combination transaction, the investor receives substantially all of its initial investment back. For target companies, a SPAC’s Inside M&A | October 2015 3 . INSIDE M&A public company status allows them to go public more quickly than the timing of a traditional public offering. It also provides a path to go public for companies whose stories may not be appreciated by public market investors. Perhaps more significantly, a business combination transaction with a SPAC provides a significant amount of flexibility for the target’s owners to receive a portion of their business combination consideration in cash and a portion in public company stock, which will allow them to participate in the future growth of the business. The SPAC Challenges While the SPAC structure provides public investors with safeguards to protect their investment, it also creates obstacles to closing a business combination. The redemption rights of SPAC stockholders and the short SPAC lifespan can SPAC Solutions Recently completed SPAC business combinations demonstrate how SPACs can be successfully utilized in the private equity dominated mergers-and-acquisitions (M&A) market.

To compete with private equity bidders’ access to cash, SPACs can enter into arrangements with third-party investors or the SPAC’s sponsors to “backstop” a specified amount of potential redemptions by public stockholders at the same price per share as the redemption price per share. These arrangements can guarantee cash certainty at closing and provide validation of the SPAC’s valuation of the business combination transaction, which in turn supports the trading price of the SPAC’s shares. These arrangements encourage targets to be more accepting of the timing and public disclosure requirements and the redemption process of SPAC bidders. create deal un-certainty and timing obstacles, making targets reluctant to sell to a SPAC. Targets often want at least some cash consideration or for a specified amount of cash to remain In addition, the attenuated timing to closing inherent in SPAC transactions for sellers who are seeking cash can be in the company for future growth—and always desire certainty of closing—but the ability of the SPAC stockholders to redeem addressed through these arrangements.

For example, the recent $500 million acquisition of Del Taco Holdings, Inc. by their shares can impact both. Even if SPAC business combination agreements include a minimum cash condition to protect a target from a closing if more redemptions than Levy Acquisition Corp.

included a novel two-step structure. In the first step, the SPAC’s sponsor and third-party investors made an upfront cash investment of $120 million in the equity expected occur, a SPAC generally cannot offer the deal protection of a breakup fee due to its lack of access to the trust account funds prior to closing a business combination. of Del Taco by purchasing stock from Del Taco stockholders and the company itself. The upfront investment provided stockholders with immediate liquidity for a portion of their Further, a large number of redemptions can put the post business combination’s public company status at risk due to a reduced market float that does not meet public company listing requirements.

The time it takes to close a SPAC business combination adds to these impediments, putting a SPAC at a dis-advantage against private equity funds and strategic buyers in a competitive bidding process. In a SPAC business combination transaction, the parties must file disclosure documents with the U.S. Securities and Exchange holdings and allowed Del Taco to re-finance its indebtedness—making its debt/equity ratio a more suitable investment for public investors.

In addition, at the time of entering into the agreement for the business combination transaction, the SPAC arranged for a $35 million private placement to take place at the closing of the business combination to provide additional cash and additional deal certainty. Moreover, because the price paid in both the step-one cash Commission (SEC), which include extensive information about the transaction and the target, including audited financial statements, pro forma financial information and other investment and the closing private placement was based on the proposed $500 million enterprise value for Del Taco in the business combination transaction, it demonstrated to the information that is typically disclosed in an IPO prospectus. The process of preparing and resolving SEC comments on these documents is time-consuming and expensive. Unless market and SPAC stockholders that third-party investors and the SPAC’s sponsor supported the proposed valuation of the transaction. The additional cash investments also helped these obstacles are addressed, some sellers may discount the bid of a SPAC and not enter into a sale process with a SPAC. support a SPAC common stock price at or in excess of the redemption price that SPAC stockholders would receive if they 4 Inside M&A | October 2015 .

INSIDE M&A redeemed their shares. The transaction was well-received by the public markets, with the SPAC’s common stock trading up to more than $5 above the per-share trust amount prior to the closing of the business combination transaction, resulting in nominal redemptions by public stockholders. SPAC Directors Cannot Take the Protection of the Business Judgment Rule for Granted Michael J. Dillon In Boulevard Acquisition Corp.’s recent acquisition of AgroFresh, a business of The Dow Chemical Company, more than two-thirds of the purchase price was paid with cash infused in the business combination in the form of a private placement completed concurrently with the closing, increased debt on the target and standby agreement under which the seller and an affiliate of sponsor agreement to provide up to $50 million in the event that the SPAC had insufficient cash to pay the full cash consideration. Similar to the Del Taco transaction, a significant portion of the cash infusion came from parties to the business combination, an affiliate of the sponsor and The Dow Chemical Company, which served as an endorsement of the business combination valuation to the market.

The AgroFresh transaction demonstrates how a business combination with a SPAC can be an alternative to the traditional spin-off transaction. These recent SPAC transactions demonstrate that SPACs can significantly increase deal certainty and their competitive position in bidding processes by utilizing one or more of the following:  An upfront cash investment to provide owners of the target immediate cash liquidity and validation that the equity value of the SPAC post-business combination is greater than the redemption price (thus discouraging redemptions)  Re-financing the post-business combination company to make it in line with debt/equity leverage ratios of public companies of similarly situated businesses  Obtaining additional support by means of a capital infusion or continued investment in the company by the sellers and/or sponsor to show confidence in the valuation of the business combination The strategic decisions made by directors of Delaware corporations are typically accorded the protection of the business judgment rule, which “is a presumption that in making a business decision, the directors of a corporation acted on an informed basis, in good faith and in the honest belief that the action taken was in the best interests of the company.” (Aronson v. Lewis, 473 A.2d 805 (Del. 1984)).

This presumption may be rebutted if, among other things, it is shown that the directors had a conflict of interest in making the decision or breached their fiduciary duties, in which case the burden shifts to the directors to defend the decision under the entire fairness standard. A recent decision by the New York State Supreme Court’s Commercial Division—in AP Services, LLP v. Lobell, et al., No.

651613/12—suggests that certain structural terms of special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) may make it more challenging for the business judgment rule to apply to decisions by SPAC directors to enter into agreements for business combination transactions. Background In June 2005, principals of a bioscience venture capital firm founded Paramount Acquisition Corp. (Paramount) as a SPAC, purchasing 2,125,000 shares of Paramount’s common stock (founder shares) for $0.01176 per share, or $25,000 in the aggregate. These principals also served as members of the board of directors of Paramount.

In October 2005, Paramount conducted its initial public offering (IPO), selling 9,775,000 units, each consisting of one share of common stock and two warrants, for a purchase price of $6 per unit, raising approximately $53 million in net proceeds after offering expenses. Approximately $52 million of the proceeds was placed into a trust account for the benefit of Paramount’s public stockholders. Following the IPO, pursuant to an agreement with the underwriters of the IPO, Paramount’s directors purchased approximately two million warrants in the open market for an aggregate purchase price of approximately $1.3 million. Inside M&A | October 2015 5 .

INSIDE M&A According to the IPO prospectus, Paramount’s purpose was to entered into forbearance agreements with its lenders and, effect a business combination transaction with an operating business in the health care industry. However, under according to the complaint in Lobell, the company admitted that the historical audited financial statements on which the Paramount’s certificate of incorporation, if a shareholderapproved acquisition of a health care entity failed to close by a “drop-dead” date [either April 27, 2007 (18 months after Business Combination Transaction was based were false. In violation of its loan covenants, and un-able to work out its debt, Chem Rx filed for bankruptcy in May 2010. The Paramount’s IPO) or October 27, 2007 (24 months after Paramount’s IPO) if Paramount had entered into a letter of intent by April 27, 2007, but the transaction had not closed by bankruptcy led to a distressed sale of Chem Rx and a Chapter 11 liquidation.

Following liquidation, the bankruptcy court established a litigation trust to prosecute claims for Chem Rx’s such date], Paramount would dissolve. In such an event, the IPO proceeds held in the trust account would be distributed in liquidation to Paramount’s public stockholders, and all of un-secured creditors. Paramount’s warrants (including those purchased by the directors) would expire worthless. In connection with the IPO, the directors waived their right to any liquidating distributions from the trust account with respect to their founder shares.

In addition, under the terms of Paramount’s certificate of incorporation, public stockholders would have the right to convert their public shares into a pro rata portion of the proceeds held in the trust account in connection with a business combination transaction if they voted against the Lobell is the litigation trust’s (i.e., the Plaintiff’s) suit against Paramount’s directors (the Directors), in which the Plaintiff alleged, inter alia, that the Directors breached their fiduciary duties of loyalty and care to Paramount by allowing Paramount to enter into the Business Combination Transaction, because, in approving the transaction, the Directors were self-interested or controlled by an interested director and, in their rush to approve the Business Combination Transaction, the Directors transaction. ignored key red flags that should have alerted them to the fact that Chem Rx's audited financial statements were untrustworthy. The Directors moved to dismiss Plaintiff’s On April 24, 2007, after having considered a number of business combination candidates, and after a different complaint, arguing, among other things, that their decision to approve the Business Combination Transaction should be protected by Delaware’s business judgment rule. potential transaction fell through, Paramount entered into a letter of intent for a business combination with Chem Rx, a long-term-care pharmacy, as well as letters of intent for two other potential business combinations, thereby extending the drop-dead date to October. On October 22, 2007, five days before the drop-dead date, Paramount acquired Chem Rx in a leveraged acquisition in which it used the cash remaining in its trust account after conversions plus approximately $160 million in debt financing and 2.5 million shares as the purchase price (the Business Combination Transaction).

In connection with the closing of the transaction, Paramount changed its Justice Marcy Friedman ruled on the motion in a June 19, 2015, decision/order (the Lobell Order), dismissing certain causes of action but denying the Directors’ motion with regard to the fiduciary breach claim. Specifically, the court rejected the Directors’ reliance on the business judgment rule in their argument for dismissal, holding that the Plaintiff alleged sufficient facts to plead a claim for breach of the duty of loyalty or a claim for breach of the duty of due care. An appeal of the Lobell Order filed by both parties remains pending in the First Department. name to Chem Rx Corporation. Analysis In April 2009, 18 months after the transaction closed, Chem Rx publicly announced that it was un-able to file its annual report for 2008, because it was in violation of certain financial covenants under its two principal credit facilities and, because of the un-certainty as to a resolution of the covenant violations, the proper accounting for the credit facility indebtedness was in doubt.

In May 2009, Chem Rx announced that it had 6 Inside M&A | October 2015 The court’s conclusion that the Plaintiff adequately pled a breach of the duty of loyalty was based on the alleged selfinterest of the majority of the Directors arising from their ownership of founder shares and warrants, which would have no value if Paramount did not close the Business Combination Transaction by the drop-dead date. This has implications for . INSIDE M&A many SPACs, because it is common for SPAC directors to flags, and that their failure to investigate in response to the red own similar founder shares or warrants. flags amounts to “gross negligence” and “intentional dereliction of their fiduciary duties.” The court acknowledged these One of the arguments the Directors made in their defense was allegations, and found that even where the SPAC’s certificate of incorporation exculpates the directors from ordinary negligence, a duty-of-care claim may be premised on gross that the Directors did not have the power to cause the acquisition to be made, because it was expressly subject to the affirmative vote of a supermajority of dis-interested stockholders. In its decision, the court acknowledged this argument in a footnote, but stated that the Defendants did not submit “legal authority addressing the impact on directors’ good faith decision-making of investor protections which may be adopted in connection with SPACS, including a requirement that a majority of IPO stockholders approve a business combination” and that the court expected this omission to be “addressed at a future stage of the litigation.” Notably, there are numerous Delaware court decisions holding that the legal effect of a fully informed stockholder vote of a transaction is that the business judgment rule applies and insulates the transaction from all attacks other than on the grounds of waste, even if a majority of the board approving the transaction was not dis-interested or independent. See In re KKR Financial Holdings LLC Shareholder Litigation, C.A. No. 9210-CB (Del.

Ch. October 14, 2014). Thus, this defense should ultimately prevail if the Defendants can show that the disclosure included by Paramount in its proxy statement for the stockholder vote was sufficient to fully inform Paramount’s stockholders about the Business Combination Transaction, as well as that it did not constitute waste, which is a low bar to meet. In a related argument, the Defendants asserted that the ability of each public stockholder to choose to convert their shares into a pro rata portion of the trust account also supported the notion that the board decision had no operative effect and, therefore, that it could not constitute a breach of fiduciary duty.

Here, too, the Defendants did not cite legal authority, which they may seek to do in a future stage of the litigation. However, neither of these arguments was dispositive of the motion before the court, as the court’s focus was solely on the sufficiency of the pleading. Thus, the court’s conclusion that the Plaintiff adequately pled a breach of the duty of care puts a focus on the adequacy of the due diligence that SPACs undertake in connection with their business combination transactions. The Plaintiff claimed that negligence in failing to heed red flags. Key Takeaways The Lobell Order highlights the need for SPAC directors to make sure that management of the SPAC engages in thorough due diligence of a business combination target, and investigates any red flags before entering into a binding agreement to fulfill their duty of care.

Directors also should ensure that the disclosure document that the SPAC prepares and circulates to its shareholders is comprehensive and highlights not only the positive aspects of the target, but also any negatives. Thus, the shareholders can make an informed decision, and approve the transaction by a majority of disinterested shareholders (as a supermajority vote of public stockholders no longer is required under SPAC charters in order to approve a business combination). By taking these two steps—even if the directors own founder shares or warrants— their decisions may qualify for the protection of the business judgment rule.

SPACs may also consider appointing one or more directors who do not own any founder shares or warrants—and are not otherwise affiliated with the principal sponsor—to act as a special independent committee to approve the transaction, thereby obviating the need to rely on an informed decision by shareholders in order to qualify for the protection of the business judgment rule. McDERMOTT CORPORATE HIGHLIGHTS McDermott Expands in Dallas’ Uptown District to Accommodate Growing Practice Our recently opened Dallas office has relocated to more expansive space in the Uptown business district. Over the past six months, the office has added almost two dozen corporate, tax controversy, technology and outsourcing lawyers. the Directors "willfully ignored" and "closed their eyes" to red Inside M&A | October 2015 7 . INSIDE M&A EDITORS For more information, please contact your regular McDermott lawyer, or: Jake Townsend +1 312 984 3673 jtownsend@mwe.com Joel L. Rubinstein +1 212 547 5336 jrubinstein@mwe.com For more information about McDermott Will & Emery visit www.mwe.com IRS Circular 230 Disclosure: To comply with requirements imposed by the IRS, we inform you that any U.S. federal tax advice contained herein (including any attachments), unless specifically stated otherwise, is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for the purposes of (i) avoiding penalties under the Internal Revenue Code or (ii) promoting, marketing or recommending to another party any transaction or matter herein. The material in this publication may not be reproduced, in whole or part without acknowledgement of its source and copyright. Inside M&A is intended to provide information of general interest in a summary manner and should not be construed as individual legal advice.

Readers should consult with their McDermott Will & Emery lawyer or other professional counsel before acting on the information contained in this publication. ©2015 McDermott Will & Emery. The following legal entities are collectively referred to as “McDermott Will & Emery,” “McDermott” or “the Firm”: McDermott Will & Emery LLP, McDermott Will & Emery AARPI, McDermott Will & Emery Belgium LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Rechtsanwälte Steuerberater LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Studio Legale Associato and McDermott Will & Emery UK LLP. These entities coordinate their activities through service agreements.

McDermott has a strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices, a separate law firm. This communication may be considered attorney advertising. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. 8 Inside M&A | October 2015 . INSIDE M&A Office Locations BOSTON BRUSSELS CHICAGO 28 State Street Boston, MA 02109 USA Tel: +1 617 535 4000 Fax: +1 617 535 3800 Avenue des Nerviens 9-31 1040 Brussels Belgium Tel: +32 2 230 50 59 Fax: +32 2 230 57 13 227 West Monroe Street Chicago, IL 60606 USA Tel: +1 312 372 2000 Fax: +1 312 984 7700 DALLAS DÜSSELDORF FRANKFURT 2501 North Harwood Street, Suite 1900 Dallas, TX 75201 USA Tel: +1 214 295 8000 Fax: +1 972 232 3098 Stadttor 1 40219 Düsseldorf Germany Tel: +49 211 30211 0 Fax: +49 211 30211 555 Feldbergstraße 35 60323 Frankfurt a. M. Germany Tel: +49 69 951145 0 Fax: + 49 69 271599 633 HOUSTON LONDON LOS ANGELES 1000 Louisiana Street, Suite 3900 Houston, TX 77002 USA Tel: +1 713 653 1700 Fax: +1 713 739 7592 Heron Tower 110 Bishopsgate London EC2N 4AY United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7577 6900 Fax: +44 20 7577 6950 2049 Century Park East, 38th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90067 USA Tel: +1 310 277 4110 Fax: +1 310 277 4730 MIAMI MILAN MUNICH 333 SE 2nd Avenue, Suite 4500 Miami, FL 33131 USA Tel: +1 305 358 3500 Fax: +1 305 347 6500 Via dei Bossi, 4/6 20121 Milan Italy Tel: +39 02 78627300 Fax: +39 02 78627333 Nymphenburger Str. 3 80335 Munich Germany Tel: +49 89 12712 0 Fax: +49 89 12712 111 NEW YORK ORANGE COUNTY PARIS 340 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10173 USA Tel: +1 212 547 5400 Fax: +1 212 547 5444 4 Park Plaza, Suite 1700 Irvine, CA 92614 USA Tel: +1 949 851 0633 Fax: +1 949 851 9348 23 rue de l'Université 75007 Paris France Tel: +33 1 81 69 15 00 Fax: +33 1 81 69 15 15 ROME SEOUL SHANGHAI Via A. Ristori, 38 00197 Rome Italy Tel: +39 06 462024 1 Fax: +39 06 489062 85 18F West Tower Mirae Asset Center1 26, Eulji-ro 5-gil, Jung-gu Seoul 04539 Korea Tel: +82 2 6030 3600 Fax: +82 2 6322 9886 MWE China Law Offices Strategic alliance with McDermott Will & Emery 28th Floor Jin Mao Building 88 Century Boulevard Shanghai Pudong New Area P.R.China 200121 Tel: +86 21 6105 0500 Fax: +86 21 6105 0501 SILICON VALLEY 275 Middlefield Road, Suite 100 Menlo Park, CA 94025 USA Tel: +1 650 815 7400 Fax: +1 650 815 7401 WASHINGTON, D.C. The McDermott Building 500 North Capitol Street, N.W. Washington, D.C.

20001 USA Tel: +1 202 756 8000 Fax: +1 202 756 8087 Inside M&A | October 2015 9 .