Description

OCTOBER 2015

Table of Contents

1

Regulatory Developments Under § 367

Affecting Transfers of Appreciated

Property to Foreign Corporations

5

Treasury Releases Guidance for

Contributions of Appreciated Property to

Partnerships with Related Foreign

Partners

8

Tax Court Decision in Altera Overturns

Important Transfer Pricing Regulations

9

Altera: How to Challenge Tax

Regulations on Administrative Law

Grounds

Regulatory Developments Under § 367 Affecting

Transfers of Appreciated Property to Foreign

Corporations

Thomas W. Giegerich and John T. Woodruff

INTRODUCTION

On September 14, the U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury) and the Internal

Revenue Service (IRS) released (1) proposed regulations under section 367 of the

Internal Revenue Code (the Code) effective (when finalized) retroactively to

transfers occurring on or after September 16 (the Proposed Section 367

Regulations), together with (2) temporary regulations under section 482, effective

immediately (applicable to tax years ending on or after September 14, 2015) (the

Temporary Section 482 Regulations).

Among other things, both sets of rules mark dramatic departures from existing guidance regarding cross-border transfers of intangibles. This article focuses on the Proposed Section 367 Regulations. SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANT CHANGES FROM PREVIOUS GUIDANCE The Proposed Section 367 Regulations:  Eliminate the foreign goodwill and going concern value exception under Treasury regulations section 1.367(d)-1T;  Limit the scope of property eligible for the active trade or business exception generally to certain tangible property and financial assets;  Allow taxpayers to apply section 367(d) (rather than 367(a)) to transfers of goodwill and going concern value to foreign corporations;  Provide that, in cases where an outbound transfer of property subject to section 367(a) constitutes a controlled transaction, the value of the property transferred is to be determined in accordance with the Temporary Section 482 Regulations; and Boston Brussels Chicago Dallas Düsseldorf Frankfurt Houston London Los Angeles Miami Milan Munich New York Orange County Paris Rome Seoul Silicon Valley Washington, D.C. Strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices (Shanghai) . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS  Eliminate the 20-year limitation on intangible property transferred under section 367(d). study, forecast, estimate, customer list or technical data; and (6) any similar item, in each case, which has substantial value BACKGROUND independent of the services of any individual. Section 367(a) Subject to various exceptions, section 367(a) provides that if, in connection with certain corporate non-recognition exchanges (described in sections 332, 351, 354, 356, or 361), a U.S. transferor transfers property to a foreign corporation (an outbound transfer), the transferee foreign corporation “will not be considered to be a corporation” with the effect that the corporate non-recognition rules are rendered inapplicable to the exchange and the U.S. transferor is required to recognize gain on the outbound transfer. Section 367(a)(3) method, program, system, procedure, campaign, survey, provides an exception for property transferred to a foreign corporation for use by the foreign corporation in the active conduct of a trade or business outside of the United States (the ATB Exception). However, the ATB Exception does not extend to certain types of property, including copyrights, inventory, accounts receivable, foreign currency and “intangible property” within the meaning of section 936(h)(3)(B), described below (936(h) Intangibles). Section 367(d) Section 367(d)(1) provides that, except as provided in regulations, if a U.S.

transferor transfers any 936(h) Intangibles to a foreign corporation in an exchange described in sections 351 or 361, the provisions of section 367(d) (and not section 367(a)) apply to the transfer. In general, under section 367(d), a U.S. transferor that transfers intangible property subject to its provisions is treated as having sold the property in exchange for a series of contingent payments that reasonably reflect the amounts that would have been received annually in the form of such payments over the useful life of the property (limited to 20 years under the current regulations). The amounts taken into account under section 367(d) must be commensurate with the Under longstanding Treasury regulations, the provisions of section 367(d) do not apply to foreign goodwill and going concern value—defined as the residual value of a business operation conducted outside of the United States after all other tangible and intangible assets have been identified and valued, and including the right to use a corporate name in a foreign country. The regulations are reflective of the sentiments of the legislature at the time of enactment of section 367(d).

Congress reasoned that “[g]oodwill and going concern value are generated by earning income, not by incurring deductions [and thus,] ordinarily, the transfer of these (or similar) intangibles does not result in avoidance of Federal income taxes.” RATIONALE FOR THE CHANGES Under the existing regulations, taxpayers have had two different positions available to them under sections 367(a) and (d) in claiming non-recognition treatment for outbound transfers of foreign goodwill and going concern value.  Goodwill and going concern value are not 936(h) Intangibles and therefore are not subject to section 367(d). Further, gain realized with respect to the outbound transfer of goodwill or going concern value is not recognized under the general rule of section 367(a) because the goodwill or going concern value is eligible for the ATB Exception; or  Even if goodwill and going concern value are considered 936(h) Intangibles the foreign goodwill exception applies. Under this scenario, taxpayers can take the position that section 367(a) does not apply to foreign goodwill or going concern value because section 367(d) provides that section 367(d) overrides section 367(a) with respect to 936(h) Intangibles. income attributable to the intangible. The preamble to the Proposed Section 367 Regulations sets forth the rationale of the Treasury and IRS for the changes 936(h) Intangibles encompass any: (1) patent, invention, formula, process, design, pattern or know-how; (2) copyright, proposed, stating that “in the context of outbound transfers, certain taxpayers attempt to avoid recognizing gain or income attributable to high-value intangible property by asserting that literary, musical or artistic composition; (3) trademark, trade name or brand name; (4) franchise, license or contract; (5) 2 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 an inappropriately large share (in many cases, the majority) of . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS the value of the property transferred is foreign goodwill or items in respect of which a U.S. transferor elects to apply going concern value that is eligible for favorable treatment under section 367.” According to the preamble, certain section 367(d) (in lieu of applying section 367(a)). Accordingly, under the proposed regulations, upon an taxpayers seek to minimize the value of property constituting 936(h) Intangibles and to maximize the value of property that may be transferred without triggering current tax, asserting a outbound transfer of foreign goodwill or going concern value, a U.S. transferor will be subject to either current gain recognition under section 367(a)(1) or the tax treatment provided under broad interpretation of the meaning of foreign goodwill and going concern value. In certain cases, the preamble states, taxpayers purport to transfer significant foreign goodwill or section 367(d). going concern value “when a large share of that value was associated with a business operated primarily by employees in the United States .

. . where the business simply earned income remotely from foreign customers.” Consequently, despite the belief expressed in the legislative history that the transfer to a foreign corporation of foreign goodwill or going concern value developed by a foreign branch was unlikely to result in abuse of the U.S.

tax system, the preamble concludes, the foreign goodwill exception has turned out to be “inconsistent with the policies of section 367 and sound tax administration and [IRS and Treasury] therefore will amend the regulations under section 367 [accordingly].” DESCRIPTION OF SIGNIFICANT CHANGES Elimination of ATB Exception for Intangible Property The Proposed Section 367 Regulations provide an exclusive list of property eligible for the ATB Exception. Under the new approach, property that is not enumerated as “eligible property”—in particular, intangible property—cannot qualify for the ATB Exception regardless of whether the property would otherwise be considered transferred for use in the active conduct of a trade or business outside of the United States. This change is meant to eliminate one of the taxpayerfavorable consequences of a finding that various items (e.g., Application of Temporary Section 482 Regulations In addition, the Proposed Section 367 Regulations provide that, in cases where an outbound transfer of property subject to section 367(a) constitutes a controlled transaction, the value of the property transferred is to be determined in accordance with the Temporary Section 482 Regulations. The Temporary Section 482 Regulations require in general that:  Compensation for related party transfers must account for all “value provided” (without defining this concept or discussing case law and other authorities to the contrary, such as Veritas), regardless of transactional characterization;  Aggregation principles should be applied to transfers that are economically interrelated and should take into account any value attributable to synergies among the transferred items, even items that are subject to differing tax treatment under the Code and regulations, under the rationale that an aggregate analysis of transactions may provide the most reliable measure of an arm's length result in these circumstances (notwithstanding the Tax Court’s conclusion in Veritas that the IRS’s aggregation approach was actually less reliable than the taxpayer’s separate valuations); and  Determinations of appropriate pricing should take into account realistic alternatives for economically equivalent transactions. goodwill) do not constitute 936(h) Intangibles.

Thus, even if the item falls outside the scope of section 367(d) and instead Together is subject to section 367(a), it no longer will be eligible for the ATB Exception to taxability under section 367(a)(1). characterization of transactions essentially irrelevant to transfer pricing, leaving the IRS more or less free to apply pure (and often questionable) economic theory in making pricing Elective Application of Section 367(d) A U.S. transferor that concludes that goodwill and going determinations. concern value are not 936(h) Intangibles may elect to apply section 367(d) to such property. This change is accomplished by revising the definition of "intangible property" to include In light of the elevation of aggregation principles in the Temporary Section 482 Regulations, the Proposed Section both property described in section 936(h)(3)(B) and other these changes are meant to render the 367 Regulations eliminate the statement in Treasury regulations section 1.367(a)-1T(b)(3)(i) providing that "the gain Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 3 .

FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS required to be recognized . . . shall in no event exceed the under section 482 to deal with inappropriate allocations of gain that would have been recognized on a taxable sale of those items of property if sold individually and without value.

Therefore, outright elimination of the foreign goodwill and going concern value exception seems unnecessary to offsetting individual losses against individual gains." The Treasury and IRS apparently were concerned that taxpayers may have interpreted the wording "if sold individually" as deal with the identified cases of perceived abuse. inconsistent with the use of aggregation principles. Elimination of 20-Year Useful Life Finally, the Proposed Section 367 Regulations eliminate the existing rule under Treasury regulations section 1.367(d)1T(c)(3) that limits the useful life of intangible property to 20 years, on the basis that the limitation can result in less than all of the income attributable to an item of intangible property being taken into account by the U.S. transferor. The Proposed Section 367 Regulations instead provide that the useful life of intangible property is the entire period during which the exploitation of the intangible property is reasonably anticipated to occur, as of the time of transfer.

This new rule may prove challenging to comply with and may be overreaching in light of recent cases such as Veritas (rejecting an IRS perpetual useful life theory). For example, in certain circumstances this new rule would encompass future research and development activities that expand upon existing intangible property transferred under section 367(d). CONCLUSION The Proposed Section 367 Regulations upend longstanding rules such as the foreign goodwill and going concern value exception and the 20-year limitation on the useful life of transferred intangible property. The elimination of the foreign goodwill and going concern value exception seems overly broad in light of the reasons articulated in the preamble to the Proposed Section 367 Regulations.

For example, while the preamble offers as a rationale cases where a large share of purported foreign goodwill and going concern value is associated with a business operated primarily by employees in the United States, this rationale is inapposite in cases where the foreign branch in fact conducted most or all of its activities outside the United States. Moreover, the concern expressed in the preamble about taxpayers overstating the value attributable to foreign goodwill and going concern value in order to reduce the value attributed to other assets that may be subject to gain recognition under section 367 should be addressable by the IRS using the tools already at its disposal 4 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 Finally, given the longstanding status of the foreign goodwill and going concern value exception and Congress’ express finding that the transfer to a foreign corporation of foreign goodwill or going concern value developed by a foreign branch is unlikely to result in abuse of the U.S. tax system, it is surprising that Treasury and IRS would choose to promulgate a proposed regulation overturning this exception that calls for an immediate effective date. As dramatic as these developments are, the companion Temporary Section 482 Regulations—presented as “clarifications” notwithstanding Veritas and other authorities to the contrary—are also very impactful, given their focus on compensating all “value provided,” aggregating economically interrelated transfers (including any value attributable to synergies) and determining alternative transactions. pricing based on realistic In a broader sense, the Proposed Section 367 Regulations should be viewed in light of Treasury’s continuing battle against inversions, regulatory limitations recently imposed on the valuation of transfers to cost-sharing arrangements and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting and Business Restructurings initiatives.

As Congress has been unable to achieve consensus on corporate tax reform and rate reduction, taxpayers have increased incentives to move business functions abroad, whether through inversion and related planning or through transferring assets and future income streams abroad, where rates are lower and U.S. taxes can be deferred. Meanwhile, the IRS has had limited success contesting taxpayers’ valuations for intangible transfers in court as demonstrated by cases such as Veritas.

The Proposed Section 367 Regulations in conjunction with the Temporary Section 482 Regulations are but the most recent salvo in this ongoing battle over so-called “income shifting”. Having failed to implement its policy positions through litigation under the existing law and guidance and through other policy initiatives, the IRS now is amending its core regulations governing outbound transfers. While this is surely a more . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS proper means of effecting Treasury’s policy positions than is The rules set forth in Notice 2015-54 are effective for transfers litigation, the breadth of these regulations and their uneasy footing in the statute and legislative history may leave them occurring on or after August 6, 2015 (and to transfers occurring before that date resulting from entity classification open to challenge in some respects (particularly in the wake of the Altera case [discussed elsewhere in this newsletter], invalidating part of the cost-sharing regulations based on the elections filed on or after August 6, 2015). IRS’s inadequate attempt to defend its regulations as being sufficiently grounded in the law). Treasury Releases Guidance for Contributions of Appreciated Property to Partnerships with Related Foreign Partners Paul Dau, Kristen E. Hazel, Elizabeth P. Lewis and Sandra McGill On August 6, 2015, 18 years after Congress authorized regulations under section 721(c) of the Internal Revenue Code (Code), the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) released Notice 2015-54 announcing that they intend to issue regulations under sections 721(c), 482 and 6662 addressing certain controlled transactions involving U.S. persons that transfer appreciated property to a partnership with foreign related partners.

The section 721(c) rules are intended to ensure that the U.S. The notice applies to the transfer of any appreciated property by a U.S. person to any partnership,existing or newly formed, domestic or foreign, if a related foreign person is a direct or indirect partner in the partnership and the U.S. transferor and one or more related persons (domestic or foreign) own more than 50 percent of the interests in partnership capital, profits, deductions or losses. BACKGROUND Prior to their repeal as part of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (the 1997 Act), sections 1491 through 1494 imposed an excise tax on certain transfers of appreciated property by a U.S. person to a foreign partnership.

These rules conceptually corresponded to the section 367 rules governing outbound transfers of appreciated property by a U.S. person to a foreign corporation. Section 367 can operate to call off the nonrecognition rules of section 351(a) and 368 in connection with such transfers under certain circumstances.

Further, in the case of transfers of certain intangible property, section 367(d) can re-characterize a contribution of intangible property to a corporation as a sale in exchange for payments contingent on the productivity, use or disposition of the intangible property, transferor takes income or gain attributable to the contributed appreciated property into account either immediately or periodically. Treasury and IRS also intend to issue regulations and require the contributor to include annually, over the shorter of the life of the asset or twenty years, an amount reflecting the amounts that would have been received over the under sections 482 and 6662 to ensure appropriate valuation of such transactions. life of the asset (or immediately on disposition of the asset). [However, see related article on recently published proposed regulations under section 367.] OVERVIEW Notice 2015-54 closes a gap that has existed with respect to outbound transfers of appreciated property to partnerships as compared to outbound transfers of appreciated property to corporations. Under the notice, the general non-recognition rule of section 721(a) will be called off with respect to contributions of built-in gain property (section 721(c) property) by a U.S.

transferor to a controlled partnership having foreign related persons as partners (directly or indirectly) unless the partnership applies rules that operate to prevent the U.S. transferor from shifting the built-in gain to related foreign persons. Following the repeal of sections 1491 through 1494, contributions of property by a U.S. person to a foreign partnership could be made on a tax-free basis—there was no longer an excise tax and the general non-recognition rules remained in force. Such contributions remained subject to the partnership tax rules applicable generally to contributions of built-in gain (or built-in loss) property (“section 704(c) property”).

Mechanically, the section 704(c) rules operate, over time and subject to limitations, to cause the contributing partner to recognize gain (or loss) with respect to the contributed property. Section 704(c) allocations must be made Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 5 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS using a reasonable method. However, the consequences of have resulted in any deferral or shift in the burden of selecting among the available methods are highly factdependent; depending on the choices made, the amount and taxation. timing of income inclusion will vary; and the use of certain available methods can affect a shift in tax burden as between the contributing partner and the non-contributing partners. Perhaps recognizing this, as well as the lack of symmetry between the rules applicable to outbound transfers to partnerships and those applicable to outbound transfers to corporate entities, Congress authorized Treasury to promulgate regulations to override the partnership nonrecognition rule and to instead impose tax on gain realized on the transfer of property to a partnership (domestic or foreign) if the gain, when recognized, would be includible in the gross income of a person other than a U.S. person. Congress also authorized Treasury to promulgate regulations applying section 367(d) principles to transfers of intangible property to a partnership. Notice 2015-54 initiates the implementation of this regulatory authority.

In addition, the notice further develops the section 482 principles applicable to contributions of property to a partnership. NOTICE 2015-54 Notice 2015-54 provides that the non-recognition rule generally applicable to contributions of property to partnerships is not applicable in the case of a transfer to a “section 721(c) partnership” unless the partnership applies the Gain Deferral Method (described below) with respect to built-in gain property contributed to it by U.S. persons (section 721(c) property). There are five requirements under the Gain Deferral Method:  First, the section 721(c) partnership is required to adopt the remedial allocation method for built-in gain with respect to section 721(c) property. The remedial method, which causes the contributing partner to recognize income in the same amount and at the same time as would occur had the contribution not been made, generally operates to eliminate any potential for shifting the tax burden associated with contributed property away from the contributing partner. The use of the remedial method is mandated even in instances where use of an alternative method would not 6 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015  Second, as long as there is any remaining built-in gain with respect to section 721(c) property, the section 721(c) partnership is required to allocate all items of section 704(b) income, gain, loss and deduction with respect to the section 721(c) property in the same proportion.

It seems clear that the rule was intended to prevent partners from unravelling the impact of remedial allocations through special allocations that might otherwise be respected. That is, to the extent the partnership has section 721(c) property, there will no longer be any ability to “specially” allocate income and loss among the partners with respect to that property. Otherwise, the notice provides little guidance with respect to interpretation of this mandate.

For example, it is not clear how this rule would apply to preferred partnership interests when the allocation scheme is designed to protect preferred capital.  Third, if the section 721(c) partnership is a foreign partnership, a U.S. transferor must comply with the reporting requirements imposed under sections 6038, 6038B, and 6046A. Form 8865 (Return of U.S.

Persons With Respect to Certain Foreign Partnerships) will be modified to include information with respect to contributions of section 721(c) property to section 721(c) partnerships.  Fourth, subject to certain exceptions, the U.S. transferor will recognize built-in gain with respect to section 721(c) property on the occurrence of an acceleration event (any transaction that would reduce the amount of remaining built-in gain that the U.S. transferor would recognize, a distribution of the built-in gain property to a person other than the U.S.

transferor, or a failure to satisfy the requirements for applying the Gain Deferral Method).  Fifth, the Gain Deferral Method must be adopted for all section 721(c) property subsequently contributed to the section 721(c) partnership by the U.S. transferor and all other U.S. transferors that are related persons until the earlier of (i) the date that no built-in gain remains with respect to any section 721(c) property to which the Gain Deferral Method first applied or (ii) the date that is 60 months after the date of the initial contribution of section 721(c) property to which the Gain Deferral Method first applied. .

FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS Treasury and IRS intend to issue regulations imposing an widening the scope of the buy-in requirement relative to prior additional requirement under the Gain Deferral Method that U.S. transferors (and, in certain cases, the section 721(c) versions of those regulations. partnership) must extend the limitations period with respect to all items related to the contributed built-in gain property through the close of the eighth full taxable year following the year of the contribution. These regulations will not require the limitations-period extension for taxable years that end before the date such regulations are published and will be effective for transfers and controlled transactions occurring on or after the date such regulations are published. The limitations period regulations together with the 60-month rule above appear intended to coordinate the new rules applicable to partnerships with the gain recognition agreement rules applicable to certain outbound transfers to corporate entities. Notice 2015-54 also addresses Treasury and IRS concerns that partnership interests received in consideration for contributed property may be incorrectly valued, reducing the amount of income or gain allocated to U.S.

partners. The IRS has broad authority under section 482 to adjust the allocation of income among parties to a controlled transaction so as to properly reflect the economics of the transaction. The notice states, however, that the IRS faces administrative difficulties when making adjustments years after a controlled transaction has occurred, because taxpayers have better access to information about their businesses and risk profiles than the IRS does. The Treasury and IRS intend to address this perceived disadvantage by augmenting current cost-sharing regulations under section 482.

While the contours of the regulations are The regulations also will provide that, in the event of a trigger based on a significant divergence of the actual returns from projected returns for controlled transactions involving a partnership, the IRS may make periodic adjustments to the result of such transaction under a method based on Treasury regulations section 1.482-7(i)(6)(v), as appropriately adjusted, as well as any necessary corresponding adjustments to section 704(b) or section 704(c) allocations. These regulations will be effective for transfers and controlled transactions occurring on or after the date of publication of the regulations. The notice points out, however, that adjustments in a current year can be scrutinized on the basis of prior year controlled transactions notwithstanding the fact that the prior year is closed. The Treasury and IRS also are considering issuing regulations under section 1.6662-6(d) requiring additional documentation for certain controlled transactions involving partnerships. These regulations may require, for example, documentation of projected returns for property contributed to a partnership (as well as attributable to related controlled transactions) and of projected partnership allocations, including projected remedial allocations, for a specified number of years. CONCLUSION Notice 2015-54 is a significant development with broad application. The rules apply to any contribution of built-in gain property (whether intangible property or not) to any controlled not described, the Treasury and IRS intend to provide guidance pertaining to the evaluation of the arm’s length partnership, new or existing, domestic or foreign, if that partnership has related foreign partners.

As a result, the sweep of the notice goes beyond the types of transactions that amount charged with respect to controlled transactions involving partnerships. The rules are expected to follow Treasury regulations section 1.482-7(g) which provides concerned Treasury and IRS (viz., outbound transfers of appreciated property to partnerships with foreign partners where the gain on the appreciated property can be shifted to guidance with respect to the arm’s length charge applicable to “platform contributions” (i.e., the buy-in charge for the contribution by a party of a resource, capability or right to the the foreign partners). For example, the rules may apply to partnership merger transactions where an “assets over” transaction structure is utilized.

In addition, the rules may cost-sharing arrangement if it is reasonably anticipated to contribute to the development of the cost-shared intangibles). The “platform contribution” concept is a relatively new one reach the deemed contribution transactions resulting upon a technical termination of an existing partnership. The notice applies immediately to contributions occurring on or after under the cost-sharing regulations and has the effect of August 6, 2015 (the date of issuance of the Notice) and even, in certain cases, before August 6, 2015 (if resulting from an Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 7 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS entity classification election filed on or after August 6, 2015). that third parties share such costs. The opinion concludes that Taxpayers therefore should consider carefully the application of these rules whenever structuring a transaction, whether the regulation “lacks a basis in fact.” among affiliates or with third parties, involving a partnership with foreign related parties. In other words, according to the full Tax Court, the IRS cannot Notice 2015-54’s extension of recent changes to the issue a valid transfer pricing regulation under the arm’s length standard that attempts to interpret how related parties “should behave” if there is no empirical evidence that unrelated parties regulations governing cost sharing arrangements to partnership transactions is also significant. These recent changes were controversial and extension into the partnership actually behave in that fashion. (In Altera there was ample evidence that unrelated parties did not charge each other for the costs of stock-based compensation.) Even though the arena will merit attention by affected taxpayers. words “arm’s length standard” do not appear in section 482, U.S.

courts and the U.S. Treasury Department’s comments on treaties (noted in Altera) have long said that the statute Finally, taxpayers should be aware that the notice gives some sense of how the IRS might examine transactions structured well before the notice was released. Tax Court Decision in Altera Overturns Important Transfer Pricing Regulations incorporates this standard, thereby limiting the IRS’s ability to reallocate among affiliates. The IRS argued in Altera that consistency of the cost-sharing regulations with the arm’s length standard is not relevant because the cost-sharing regulations are part of an “elective” regulatory regime for cost sharing. The Tax Court dismissed On July 27, 2015, the U.S.

Tax Court issued a stunning rebuke the IRS attempt to recharacterize the relevant provisions as “elective,” noting that in the regulatory process the IRS rejected taxpayer suggestions to make the requirement a true to the IRS by invalidating the part of the Internal Revenue Services’ (IRS) cost-sharing regulations under section 482 of the Internal Revenue Code that says taxpayers have to take safe harbor. (There are other parts of the pricing regulations that taxpayers can truly elect and that Altera should not disturb.) Steven P. Hannes into account, among other costs, the costs of stock-based compensation.

The Altera decision should also support the many taxpayers who have questioned the separate section 482 regulatory requirement that cost-based transfer pricing (e.g., cost-plus pricing for services) must include the cost of stock-based compensation. Taxpayers with cost-sharing agreements or other transfer pricing that previously took into account such stock-based compensation costs should consider amending their returns and filing claims for refunds for open years. Taxpayers who followed the approach sustained in Altera may want to review their tax provisions. The opinion, reviewed by the full Tax Court, is important for transfer pricing beyond cost sharing and stock-based compensation costs. The Tax Court held that, as an interpretation of the “arm’s length standard,” the regulation is invalid because there is no empirical basis for the proposition 8 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 The Tax Court decision may comfort those taxpayers already challenging in court the validity of other provisions of the section 482 regulations that “overreach” (e.g., 3M’s pending challenge to the “foreign legal requirements” provision in the regulations). The holding of the court in Altera has relevance to ongoing debates about whether certain Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) proposals coming from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), such as those asserting that “control” over certain activities is a prerequisite for a related party to claim intangibles profits (or losses), could be adopted administratively in the United States.

Altera lends support to those who believe the IRS and Treasury could not adopt these proposals as valid regulatory interpretations of the arm’s length standard of section 482; instead adoption could only occur through a statutory amendment by Congress. . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS If the government does not acquiesce in Altera, and does not remove the stock-based compensation provisions from the section 482 regulations, then taxpayers will have choices. Those who benefit from including the costs of stock-based compensation in the contexts of cost sharing and transfer pricing, such as a foreign company with significant stockbased compensation costs that provides services or goods to a U.S. affiliate, can continue to rely on the regulations. Those taxpayers who, like Altera, do not benefit from including such costs now have a significant case upon which to rely. Unfortunately, it would not be surprising if the government appeals Altera even though sound tax policy and administrative considerations would argue that it should accept the decision and move on to other issues. However, given the record on this issue, the government will likely have an uphill battle should it appeal. In conclusion, one might speculate whether Altera could mark the beginning of the end of the last 20 years of frequent theory-based (not fact-based) approaches in regulations as to how related parties should behave with respect to their transfer pricing.

Even before the issuance of the 1994 regulations, as well as since, the IRS has lost cases in court that were based on theories IRS developed in litigation (essentially all the cases it has litigated). It became apparent to the IRS a few years ago that facts, not theories, convince judges (at least under the current statute) and IRS decided to change its approach to transfer pricing litigation. The IRS has stated that it is focusing on improving its track record in court in part by doing a better job of mastering the facts in litigating a case. Recently, IRS gave its first response to the question whether Altera will cause IRS and Treasury to reexamine and revise the theory-based parts of pricing regulations. As discussed in another article in this edition of our newsletter, on September 14, 2015, IRS issued temporary regulations under 482 (involving transfer pricing issues not at issue in Altera) that, unfortunately, indicate that the IRS still is prepared to issue theory-based transfer pricing rules.

The preamble to temporary return 482 regulations does not mention Altera by name or explain why the IRS believes it appropriate to issue another theory-based pricing regulation not supported by empirical data. Altera: How to Challenge Tax Regulations on Administrative Law Grounds Roger J. Jones, Andrew R. Roberson and Lowell D.

Yoder The U.S. Tax Court’s opinion in Altera, discussed in the preceding article, provides a thorough analysis of how to challenge tax regulations on administrative law grounds. In Altera, the U.S. Tax Court invalidated regulations under section 482 requiring participants in qualified cost-sharing agreements (CSAs) to include stock-based compensation costs in the cost pool to comply with the arm’s-length standard.

The discussion below summarizes the history of those regulations and focuses primarily on the court’s holding and the implications of that holding with respect to administrative law issues. BACKGROUND In 2005, the Tax Court held in Xilinx Inc. v. Commissioner, 125 T.C.

37 (2005), that, under cost-sharing regulations promulgated in 1995, controlled entities entering into CSAs need not share stock-based compensation costs because parties operating at arm’s-length would not do so. The Ninth Circuit affirmed, holding that the all costs requirement should be construed as not applying to stock-based compensation because the regulations should be interpreted to accomplish the statutory purpose of grounding the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) allocation authority in the principle of “parity between taxpayers in uncontrolled transactions and taxpayers in controlled transactions,” and the U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury) technical explanation of the income tax convention between the United States and Ireland confirmed that the commensurate-with-income standard was meant to work consistently with the arm’s-length standard. While the dispute in Xilinx was ongoing, but before the Tax Court’s opinion was issued, the IRS and Treasury proposed amendments in 2002 to the 1995 cost-sharing regulations purporting to clarify that stock-based compensation must be taken into account in determining operating expenses under Treasury regulations section 1.482-7(d)(1), to provide rules for measuring stock-based compensation costs, and to include express provisions to coordinate the cost sharing rules of Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 9 .

FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS Treasury regulations section 1.482-7 with the arm’s-length invalid because it violated the APA. Although similar APA standard of Treasury regulatiosn section 1.482-1. Several parties submitted written comments to Treasury, and four challenges to tax regulations have been raised in the past, (most notably in basis overstatement cases culminating in the individuals spoke at a public hearing. Many of the commentators informed Treasury that they knew of no transactions between unrelated parties, including any cost- Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Home Concrete & Supply, LLC, 132 S.Ct.

1836 (2012)), courts had not addressed in detail the specific arguments raised by Altera. sharing arrangement, service agreement, or other contract, that required one party to pay or reimburse the other party for amounts attributable to stock-based compensation. Additionally, several commentators identified arm’s-length agreements in which stock-based compensation was not shared or reimbursed. The APA establishes several administrative law requirements for the promulgation of rules and regulations by government agencies. For example, agencies generally must provide the public with notice of, and the opportunity to comment on, proposed regulations that are intended to carry the force of law (i.e., “substantive rules”), and the agency must consider any Despite the comments, the IRS and Treasury issued final rules in 2003 explicitly requiring parties to CSAs to share stockbased compensation costs. The final rule also added comments before promulgating final regulations.

However, this requirement does not apply to interpretive rules or when the agency determines, and explains in detail, that good cause regulations providing that CSAs produce an arm’s-length result only if the parties’ costs are determined in accordance with the final rule. Treasury’s files underlying the final rules did not exists for not providing notice and the opportunity for comment. The APA also requires that a court set aside agency action that is “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or contain any expert opinions, empirical data, articles, papers or surveys supporting a determination that the amounts attributable to stock-based compensation must be included in otherwise not in accordance with law.” In Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Association of the United States v.

State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co, 463 U.S. 29 (1983), the the cost pool of CSAs to achieve an arm’s-length result. There was also no evidence that Treasury had searched any database that could have contained agreements between Supreme Court explained that an agency must have “engaged in reasoned decisionmaking,” which means “the agency must examine the relevant data and articulate a satisfactory unrelated parties relating to joint undertakings or the provision of services, nor that Treasury was aware of any written contract between unrelated parties that required one party to explanation for its action including a ‘rational connection between the facts found and the choice made.’” Finally, the APA contains a harmless error rule reflecting the notion that if pay or reimburse the other party for amounts attributable to stock-based compensation.

Nor was there any evidence of any actual transaction between unrelated parties in which one the agency’s mistake did not affect the outcome or prejudice the petitioning party, the agency action can be upheld despite the mistake. In Mayo Found. for Med.

Educ. & Research v. party paid or reimbursed the other party for amounts attributable to stock-based compensation. The preamble United States, 562 U.S.

44, 57 (2011), the Supreme Court made clear that the APA applies to tax rules and regulations. responded to certain comments, but did not justify the final rule on the basis of any modification or abandonment of the arm’slength standard. The preamble also concluded that the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) did not apply to the regulations. ALTERA In Altera, Altera filed a petition with the Tax Court challenging the IRS’s allocation of income in accordance with the 2003 cost-sharing regulations. Altera argued that the final rule requiring participants in CSAs to share stock-based compensation costs to achieve an arm’s-length result was 10 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 In Altera, a unanimous Tax Court found that Treasury failed to engage in reasoned decision-making as required under the APA and State Farm.

Specifically, the court concluded that, in failing to rationally connect the choice it made with the facts, Treasury had engaged in arbitrary and capricious decisionmaking. Treasury had failed to engage in material fact finding or to follow evidence-gathering procedures and the regulatory record lacked any evidence to support the result set forth in the 2003 regulations. Treasury had failed to respond to significant comments when it issued the 2003 regulations and its conclusion that the 2003 regulations were consistent with .

FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS the arm’s-length standard in fact was contrary to all of the continue to rely on provisions like the applicable-federal-rate- evidence before it. Accordingly, the court ruled that the 2003 regulations were invalid. In doing so, the Tax Court provided a based safe harbor for intercompany interest, even though the results of the safe harbor undoubtedly depart from an arm’s-length result in many cases. The arm’s-length standard that the Tax Court discussed in Altera limits the authority of the IRS to issue thorough analysis of the application of administrative law principles to Treasury regulations.

In particular, the court made the following determinations:  Treasury regulations issued pursuant to section 7805(a) are legislative regulations because the IRS intends them to “carry the force of law”; thus, Treasury is required to follow the APA’s notice and comment requirements absent satisfaction of the good cause exception.  Tax regulations must be the product of reasoned decisionmaking; thus, they must have a basis in fact, there must be a rational connection between the facts found and the choice made, significant comments must be responded to, and the final rule may not be contrary to the evidence presented before the final rule is issued.  The harmless error exception requires at least a reasonable showing by Treasury that it had sufficient alternative reasons for adopting the final rule (at the time the rule was adopted and not in hindsight) in light of its mistake. PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS A practical question is what is the impact of Altera? Obviously, the opinion is a victory for taxpayers disputing the 2003 regulations dealing with stock-based compensation, and affected taxpayers now will have to consider whether to amend their cost-sharing agreements going forward to reflect Altera, as well as whether and when “clawback” provisions of existing agreements might be triggered. But the impact of the case and its limits on the IRS’s rulemaking authority also could be felt more broadly in the transfer pricing area, as taxpayers may challenge other current (and possibly future) regulation provisions that might not be adequately grounded in the arm’slength standard. It should be noted, however, that all provisions of the transfer pricing regulations remain binding on the IRS regardless of whether such provisions comport with general arm’s-length principles. The Tax Court’s opinion in Xilinx, as well as other Tax Court cases, treats IRS published guidance as concessions by the IRS on an issue given that taxpayers rely on such positions in planning their transactions.

For example, taxpayers clearly can transfer pricing regulations; the IRS cannot impose regulatory requirements under section 482 that violate that standard. Even more broadly, the impact of the decision may be felt throughout the tax law, because the decision potentially calls into question the promulgation process for many tax regulations that are currently on the books. Treasury has historically taken the position (incorrectly, as Altera demonstrates) that regulations issued pursuant to section 7805(a) are not covered by the APA and many tax regulations lack an extensive discussion of the justification of the rules as envisioned by State Farm. Taxpayers challenging regulations may want to review regulatory history to determine whether, under Altera, Treasury failed to engage in reasoned decision-making.

In this regard, Altera, in conjunction with Dominion Resources, Inc. v. U.S., 681 F.3d 1313 (2012), where the U.S.

Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit applied the arbitrary and capricious standard to invalidate Treasury regulations section 1.263A-11(e)(1)(ii)(B) on the ground that Treasury failed to provide an explanation of the reasons behind the regulation, provides an excellent roadmap for undertaking the analysis. Finally, it remains to be seen whether the analysis in Altera may strengthen arguments against the IRS’s reliance on temporary regulations (particularly those issued before 1989 that have never been finalized) and situations where the IRS applies final regulations retroactively. It should be noted that Microsoft, which is currently involved in a summons enforcement action with the government in the District Court for the Western District of Washington, recently filed a notice of supplemental authority arguing to that court that Altera is relevant to Microsoft’s argument that it will make a substantial preliminary showing that enforcing the summonses would be an abuse of the court’s process, in part by showing that the IRS violated the APA in promulgating the temporary regulation at issue in that case. Altera’s successful motion for partial summary judgment did not dispose of all issues in the case; thus, the Tax Court has not issued a decision from which the IRS can appeal the case. Once the remaining issues are resolved and a decision is entered, the IRS will need to decide whether to appeal the case (presumably to the Ninth Circuit).

It is impossible to predict what the circuit court would decide, but it bears noting that the Ninth Circuit affirmed the Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 11 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS Tax Court’s decision in Xilinx and the Tax Court in Altera cited extensively to Supreme Court and Ninth Circuit precedent (as well as case law from the D.C. Circuit, which hears the majority of administrative law issues) to support its holding that the regulation was invalid. EDITORS Altera is a significant case, both in the specific context of transfer Partner-in-Charge, New York Tax Practice +1 212 547 5335 tgiegerich@mwe.com pricing and in the general context of the validity of tax regulations. Taxpayers that have followed the 2003 regulations should consider whether to change their transfer pricing practices going forward and whether to file protective refund claims for prior open years. Additionally, as noted above, taxpayers with clawback provisions should consider whether the clawback obligation has been triggered. Taxpayers outside the specific context of the 2003 regulations should also consider the requirements of the APA, including the notice-and-comment procedures, when evaluating whether to take a position that is contrary to a Treasury regulation. For more information, please contact your regular McDermott lawyer, or: Thomas W.

Giegerich Blake D. Rubin Partner-in-Charge, Washington, D.C. Tax Practice +1 202 756 8424 bdrubin@mwe.com For more information about McDermott Will & Emery visit www.mwe.com The material in this publication may not be reproduced, in whole or part without acknowledgement of its source and copyright.

Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments is intended to provide information of general interest in a summary manner and should not be construed as individual legal advice. Readers should consult with their McDermott Will & Emery lawyer or other professional counsel before acting on the information contained in this publication. ©2015 McDermott Will & Emery. The following legal entities are collectively referred to as “McDermott Will & Emery,” “McDermott” or “the Firm”: McDermott Will & Emery LLP, McDermott Will & Emery AARPI, McDermott Will & Emery Belgium LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Rechtsanwälte Steuerberater LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Studio Legale Associato and McDermott Will & Emery UK LLP.

These entities coordinate their activities through service agreements. McDermott has a strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices, a separate law firm. This communication may be considered attorney advertising. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. 12 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 .

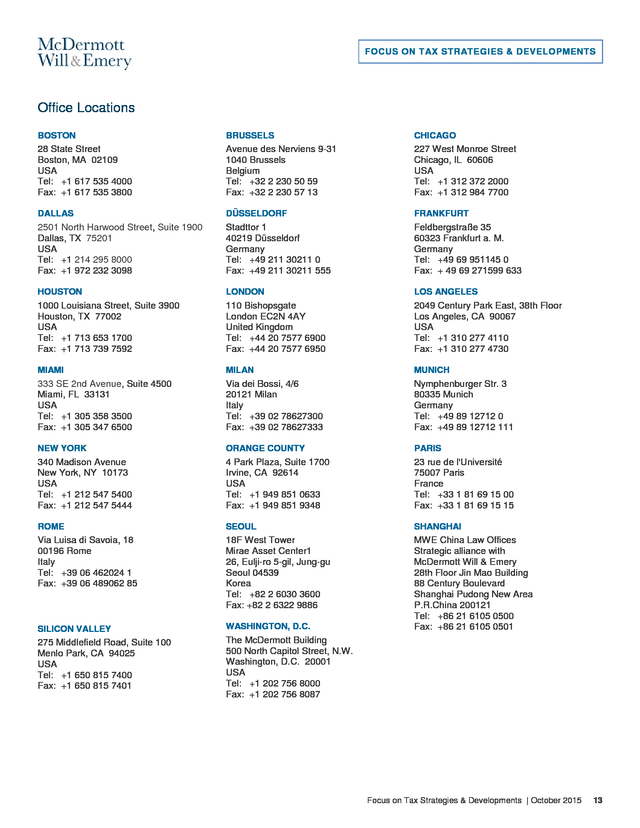

FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS Office Locations BOSTON BRUSSELS CHICAGO 28 State Street Boston, MA 02109 USA Tel: +1 617 535 4000 Fax: +1 617 535 3800 Avenue des Nerviens 9-31 1040 Brussels Belgium Tel: +32 2 230 50 59 Fax: +32 2 230 57 13 227 West Monroe Street Chicago, IL 60606 USA Tel: +1 312 372 2000 Fax: +1 312 984 7700 DALLAS DÜSSELDORF FRANKFURT 2501 North Harwood Street, Suite 1900 Dallas, TX 75201 USA Tel: +1 214 295 8000 Fax: +1 972 232 3098 Stadttor 1 40219 Düsseldorf Germany Tel: +49 211 30211 0 Fax: +49 211 30211 555 Feldbergstraße 35 60323 Frankfurt a. M. Germany Tel: +49 69 951145 0 Fax: + 49 69 271599 633 HOUSTON LONDON LOS ANGELES 1000 Louisiana Street, Suite 3900 Houston, TX 77002 USA Tel: +1 713 653 1700 Fax: +1 713 739 7592 110 Bishopsgate London EC2N 4AY United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7577 6900 Fax: +44 20 7577 6950 2049 Century Park East, 38th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90067 USA Tel: +1 310 277 4110 Fax: +1 310 277 4730 MIAMI MILAN MUNICH 333 SE 2nd Avenue, Suite 4500 Miami, FL 33131 USA Tel: +1 305 358 3500 Fax: +1 305 347 6500 Via dei Bossi, 4/6 20121 Milan Italy Tel: +39 02 78627300 Fax: +39 02 78627333 Nymphenburger Str. 3 80335 Munich Germany Tel: +49 89 12712 0 Fax: +49 89 12712 111 NEW YORK ORANGE COUNTY PARIS 340 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10173 USA Tel: +1 212 547 5400 Fax: +1 212 547 5444 4 Park Plaza, Suite 1700 Irvine, CA 92614 USA Tel: +1 949 851 0633 Fax: +1 949 851 9348 23 rue de l'Université 75007 Paris France Tel: +33 1 81 69 15 00 Fax: +33 1 81 69 15 15 ROME SEOUL SHANGHAI Via Luisa di Savoia, 18 00196 Rome Italy Tel: +39 06 462024 1 Fax: +39 06 489062 85 18F West Tower Mirae Asset Center1 26, Eulji-ro 5-gil, Jung-gu Seoul 04539 Korea Tel: +82 2 6030 3600 Fax: +82 2 6322 9886 SILICON VALLEY WASHINGTON, D.C. MWE China Law Offices Strategic alliance with McDermott Will & Emery 28th Floor Jin Mao Building 88 Century Boulevard Shanghai Pudong New Area P.R.China 200121 Tel: +86 21 6105 0500 Fax: +86 21 6105 0501 275 Middlefield Road, Suite 100 Menlo Park, CA 94025 USA Tel: +1 650 815 7400 Fax: +1 650 815 7401 The McDermott Building 500 North Capitol Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 USA Tel: +1 202 756 8000 Fax: +1 202 756 8087 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 13 .

Among other things, both sets of rules mark dramatic departures from existing guidance regarding cross-border transfers of intangibles. This article focuses on the Proposed Section 367 Regulations. SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANT CHANGES FROM PREVIOUS GUIDANCE The Proposed Section 367 Regulations:  Eliminate the foreign goodwill and going concern value exception under Treasury regulations section 1.367(d)-1T;  Limit the scope of property eligible for the active trade or business exception generally to certain tangible property and financial assets;  Allow taxpayers to apply section 367(d) (rather than 367(a)) to transfers of goodwill and going concern value to foreign corporations;  Provide that, in cases where an outbound transfer of property subject to section 367(a) constitutes a controlled transaction, the value of the property transferred is to be determined in accordance with the Temporary Section 482 Regulations; and Boston Brussels Chicago Dallas Düsseldorf Frankfurt Houston London Los Angeles Miami Milan Munich New York Orange County Paris Rome Seoul Silicon Valley Washington, D.C. Strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices (Shanghai) . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS  Eliminate the 20-year limitation on intangible property transferred under section 367(d). study, forecast, estimate, customer list or technical data; and (6) any similar item, in each case, which has substantial value BACKGROUND independent of the services of any individual. Section 367(a) Subject to various exceptions, section 367(a) provides that if, in connection with certain corporate non-recognition exchanges (described in sections 332, 351, 354, 356, or 361), a U.S. transferor transfers property to a foreign corporation (an outbound transfer), the transferee foreign corporation “will not be considered to be a corporation” with the effect that the corporate non-recognition rules are rendered inapplicable to the exchange and the U.S. transferor is required to recognize gain on the outbound transfer. Section 367(a)(3) method, program, system, procedure, campaign, survey, provides an exception for property transferred to a foreign corporation for use by the foreign corporation in the active conduct of a trade or business outside of the United States (the ATB Exception). However, the ATB Exception does not extend to certain types of property, including copyrights, inventory, accounts receivable, foreign currency and “intangible property” within the meaning of section 936(h)(3)(B), described below (936(h) Intangibles). Section 367(d) Section 367(d)(1) provides that, except as provided in regulations, if a U.S.

transferor transfers any 936(h) Intangibles to a foreign corporation in an exchange described in sections 351 or 361, the provisions of section 367(d) (and not section 367(a)) apply to the transfer. In general, under section 367(d), a U.S. transferor that transfers intangible property subject to its provisions is treated as having sold the property in exchange for a series of contingent payments that reasonably reflect the amounts that would have been received annually in the form of such payments over the useful life of the property (limited to 20 years under the current regulations). The amounts taken into account under section 367(d) must be commensurate with the Under longstanding Treasury regulations, the provisions of section 367(d) do not apply to foreign goodwill and going concern value—defined as the residual value of a business operation conducted outside of the United States after all other tangible and intangible assets have been identified and valued, and including the right to use a corporate name in a foreign country. The regulations are reflective of the sentiments of the legislature at the time of enactment of section 367(d).

Congress reasoned that “[g]oodwill and going concern value are generated by earning income, not by incurring deductions [and thus,] ordinarily, the transfer of these (or similar) intangibles does not result in avoidance of Federal income taxes.” RATIONALE FOR THE CHANGES Under the existing regulations, taxpayers have had two different positions available to them under sections 367(a) and (d) in claiming non-recognition treatment for outbound transfers of foreign goodwill and going concern value.  Goodwill and going concern value are not 936(h) Intangibles and therefore are not subject to section 367(d). Further, gain realized with respect to the outbound transfer of goodwill or going concern value is not recognized under the general rule of section 367(a) because the goodwill or going concern value is eligible for the ATB Exception; or  Even if goodwill and going concern value are considered 936(h) Intangibles the foreign goodwill exception applies. Under this scenario, taxpayers can take the position that section 367(a) does not apply to foreign goodwill or going concern value because section 367(d) provides that section 367(d) overrides section 367(a) with respect to 936(h) Intangibles. income attributable to the intangible. The preamble to the Proposed Section 367 Regulations sets forth the rationale of the Treasury and IRS for the changes 936(h) Intangibles encompass any: (1) patent, invention, formula, process, design, pattern or know-how; (2) copyright, proposed, stating that “in the context of outbound transfers, certain taxpayers attempt to avoid recognizing gain or income attributable to high-value intangible property by asserting that literary, musical or artistic composition; (3) trademark, trade name or brand name; (4) franchise, license or contract; (5) 2 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 an inappropriately large share (in many cases, the majority) of . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS the value of the property transferred is foreign goodwill or items in respect of which a U.S. transferor elects to apply going concern value that is eligible for favorable treatment under section 367.” According to the preamble, certain section 367(d) (in lieu of applying section 367(a)). Accordingly, under the proposed regulations, upon an taxpayers seek to minimize the value of property constituting 936(h) Intangibles and to maximize the value of property that may be transferred without triggering current tax, asserting a outbound transfer of foreign goodwill or going concern value, a U.S. transferor will be subject to either current gain recognition under section 367(a)(1) or the tax treatment provided under broad interpretation of the meaning of foreign goodwill and going concern value. In certain cases, the preamble states, taxpayers purport to transfer significant foreign goodwill or section 367(d). going concern value “when a large share of that value was associated with a business operated primarily by employees in the United States .

. . where the business simply earned income remotely from foreign customers.” Consequently, despite the belief expressed in the legislative history that the transfer to a foreign corporation of foreign goodwill or going concern value developed by a foreign branch was unlikely to result in abuse of the U.S.

tax system, the preamble concludes, the foreign goodwill exception has turned out to be “inconsistent with the policies of section 367 and sound tax administration and [IRS and Treasury] therefore will amend the regulations under section 367 [accordingly].” DESCRIPTION OF SIGNIFICANT CHANGES Elimination of ATB Exception for Intangible Property The Proposed Section 367 Regulations provide an exclusive list of property eligible for the ATB Exception. Under the new approach, property that is not enumerated as “eligible property”—in particular, intangible property—cannot qualify for the ATB Exception regardless of whether the property would otherwise be considered transferred for use in the active conduct of a trade or business outside of the United States. This change is meant to eliminate one of the taxpayerfavorable consequences of a finding that various items (e.g., Application of Temporary Section 482 Regulations In addition, the Proposed Section 367 Regulations provide that, in cases where an outbound transfer of property subject to section 367(a) constitutes a controlled transaction, the value of the property transferred is to be determined in accordance with the Temporary Section 482 Regulations. The Temporary Section 482 Regulations require in general that:  Compensation for related party transfers must account for all “value provided” (without defining this concept or discussing case law and other authorities to the contrary, such as Veritas), regardless of transactional characterization;  Aggregation principles should be applied to transfers that are economically interrelated and should take into account any value attributable to synergies among the transferred items, even items that are subject to differing tax treatment under the Code and regulations, under the rationale that an aggregate analysis of transactions may provide the most reliable measure of an arm's length result in these circumstances (notwithstanding the Tax Court’s conclusion in Veritas that the IRS’s aggregation approach was actually less reliable than the taxpayer’s separate valuations); and  Determinations of appropriate pricing should take into account realistic alternatives for economically equivalent transactions. goodwill) do not constitute 936(h) Intangibles.

Thus, even if the item falls outside the scope of section 367(d) and instead Together is subject to section 367(a), it no longer will be eligible for the ATB Exception to taxability under section 367(a)(1). characterization of transactions essentially irrelevant to transfer pricing, leaving the IRS more or less free to apply pure (and often questionable) economic theory in making pricing Elective Application of Section 367(d) A U.S. transferor that concludes that goodwill and going determinations. concern value are not 936(h) Intangibles may elect to apply section 367(d) to such property. This change is accomplished by revising the definition of "intangible property" to include In light of the elevation of aggregation principles in the Temporary Section 482 Regulations, the Proposed Section both property described in section 936(h)(3)(B) and other these changes are meant to render the 367 Regulations eliminate the statement in Treasury regulations section 1.367(a)-1T(b)(3)(i) providing that "the gain Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 3 .

FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS required to be recognized . . . shall in no event exceed the under section 482 to deal with inappropriate allocations of gain that would have been recognized on a taxable sale of those items of property if sold individually and without value.

Therefore, outright elimination of the foreign goodwill and going concern value exception seems unnecessary to offsetting individual losses against individual gains." The Treasury and IRS apparently were concerned that taxpayers may have interpreted the wording "if sold individually" as deal with the identified cases of perceived abuse. inconsistent with the use of aggregation principles. Elimination of 20-Year Useful Life Finally, the Proposed Section 367 Regulations eliminate the existing rule under Treasury regulations section 1.367(d)1T(c)(3) that limits the useful life of intangible property to 20 years, on the basis that the limitation can result in less than all of the income attributable to an item of intangible property being taken into account by the U.S. transferor. The Proposed Section 367 Regulations instead provide that the useful life of intangible property is the entire period during which the exploitation of the intangible property is reasonably anticipated to occur, as of the time of transfer.

This new rule may prove challenging to comply with and may be overreaching in light of recent cases such as Veritas (rejecting an IRS perpetual useful life theory). For example, in certain circumstances this new rule would encompass future research and development activities that expand upon existing intangible property transferred under section 367(d). CONCLUSION The Proposed Section 367 Regulations upend longstanding rules such as the foreign goodwill and going concern value exception and the 20-year limitation on the useful life of transferred intangible property. The elimination of the foreign goodwill and going concern value exception seems overly broad in light of the reasons articulated in the preamble to the Proposed Section 367 Regulations.

For example, while the preamble offers as a rationale cases where a large share of purported foreign goodwill and going concern value is associated with a business operated primarily by employees in the United States, this rationale is inapposite in cases where the foreign branch in fact conducted most or all of its activities outside the United States. Moreover, the concern expressed in the preamble about taxpayers overstating the value attributable to foreign goodwill and going concern value in order to reduce the value attributed to other assets that may be subject to gain recognition under section 367 should be addressable by the IRS using the tools already at its disposal 4 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 Finally, given the longstanding status of the foreign goodwill and going concern value exception and Congress’ express finding that the transfer to a foreign corporation of foreign goodwill or going concern value developed by a foreign branch is unlikely to result in abuse of the U.S. tax system, it is surprising that Treasury and IRS would choose to promulgate a proposed regulation overturning this exception that calls for an immediate effective date. As dramatic as these developments are, the companion Temporary Section 482 Regulations—presented as “clarifications” notwithstanding Veritas and other authorities to the contrary—are also very impactful, given their focus on compensating all “value provided,” aggregating economically interrelated transfers (including any value attributable to synergies) and determining alternative transactions. pricing based on realistic In a broader sense, the Proposed Section 367 Regulations should be viewed in light of Treasury’s continuing battle against inversions, regulatory limitations recently imposed on the valuation of transfers to cost-sharing arrangements and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting and Business Restructurings initiatives.

As Congress has been unable to achieve consensus on corporate tax reform and rate reduction, taxpayers have increased incentives to move business functions abroad, whether through inversion and related planning or through transferring assets and future income streams abroad, where rates are lower and U.S. taxes can be deferred. Meanwhile, the IRS has had limited success contesting taxpayers’ valuations for intangible transfers in court as demonstrated by cases such as Veritas.

The Proposed Section 367 Regulations in conjunction with the Temporary Section 482 Regulations are but the most recent salvo in this ongoing battle over so-called “income shifting”. Having failed to implement its policy positions through litigation under the existing law and guidance and through other policy initiatives, the IRS now is amending its core regulations governing outbound transfers. While this is surely a more . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS proper means of effecting Treasury’s policy positions than is The rules set forth in Notice 2015-54 are effective for transfers litigation, the breadth of these regulations and their uneasy footing in the statute and legislative history may leave them occurring on or after August 6, 2015 (and to transfers occurring before that date resulting from entity classification open to challenge in some respects (particularly in the wake of the Altera case [discussed elsewhere in this newsletter], invalidating part of the cost-sharing regulations based on the elections filed on or after August 6, 2015). IRS’s inadequate attempt to defend its regulations as being sufficiently grounded in the law). Treasury Releases Guidance for Contributions of Appreciated Property to Partnerships with Related Foreign Partners Paul Dau, Kristen E. Hazel, Elizabeth P. Lewis and Sandra McGill On August 6, 2015, 18 years after Congress authorized regulations under section 721(c) of the Internal Revenue Code (Code), the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) released Notice 2015-54 announcing that they intend to issue regulations under sections 721(c), 482 and 6662 addressing certain controlled transactions involving U.S. persons that transfer appreciated property to a partnership with foreign related partners.

The section 721(c) rules are intended to ensure that the U.S. The notice applies to the transfer of any appreciated property by a U.S. person to any partnership,existing or newly formed, domestic or foreign, if a related foreign person is a direct or indirect partner in the partnership and the U.S. transferor and one or more related persons (domestic or foreign) own more than 50 percent of the interests in partnership capital, profits, deductions or losses. BACKGROUND Prior to their repeal as part of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (the 1997 Act), sections 1491 through 1494 imposed an excise tax on certain transfers of appreciated property by a U.S. person to a foreign partnership.

These rules conceptually corresponded to the section 367 rules governing outbound transfers of appreciated property by a U.S. person to a foreign corporation. Section 367 can operate to call off the nonrecognition rules of section 351(a) and 368 in connection with such transfers under certain circumstances.

Further, in the case of transfers of certain intangible property, section 367(d) can re-characterize a contribution of intangible property to a corporation as a sale in exchange for payments contingent on the productivity, use or disposition of the intangible property, transferor takes income or gain attributable to the contributed appreciated property into account either immediately or periodically. Treasury and IRS also intend to issue regulations and require the contributor to include annually, over the shorter of the life of the asset or twenty years, an amount reflecting the amounts that would have been received over the under sections 482 and 6662 to ensure appropriate valuation of such transactions. life of the asset (or immediately on disposition of the asset). [However, see related article on recently published proposed regulations under section 367.] OVERVIEW Notice 2015-54 closes a gap that has existed with respect to outbound transfers of appreciated property to partnerships as compared to outbound transfers of appreciated property to corporations. Under the notice, the general non-recognition rule of section 721(a) will be called off with respect to contributions of built-in gain property (section 721(c) property) by a U.S.

transferor to a controlled partnership having foreign related persons as partners (directly or indirectly) unless the partnership applies rules that operate to prevent the U.S. transferor from shifting the built-in gain to related foreign persons. Following the repeal of sections 1491 through 1494, contributions of property by a U.S. person to a foreign partnership could be made on a tax-free basis—there was no longer an excise tax and the general non-recognition rules remained in force. Such contributions remained subject to the partnership tax rules applicable generally to contributions of built-in gain (or built-in loss) property (“section 704(c) property”).

Mechanically, the section 704(c) rules operate, over time and subject to limitations, to cause the contributing partner to recognize gain (or loss) with respect to the contributed property. Section 704(c) allocations must be made Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015 5 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS using a reasonable method. However, the consequences of have resulted in any deferral or shift in the burden of selecting among the available methods are highly factdependent; depending on the choices made, the amount and taxation. timing of income inclusion will vary; and the use of certain available methods can affect a shift in tax burden as between the contributing partner and the non-contributing partners. Perhaps recognizing this, as well as the lack of symmetry between the rules applicable to outbound transfers to partnerships and those applicable to outbound transfers to corporate entities, Congress authorized Treasury to promulgate regulations to override the partnership nonrecognition rule and to instead impose tax on gain realized on the transfer of property to a partnership (domestic or foreign) if the gain, when recognized, would be includible in the gross income of a person other than a U.S. person. Congress also authorized Treasury to promulgate regulations applying section 367(d) principles to transfers of intangible property to a partnership. Notice 2015-54 initiates the implementation of this regulatory authority.

In addition, the notice further develops the section 482 principles applicable to contributions of property to a partnership. NOTICE 2015-54 Notice 2015-54 provides that the non-recognition rule generally applicable to contributions of property to partnerships is not applicable in the case of a transfer to a “section 721(c) partnership” unless the partnership applies the Gain Deferral Method (described below) with respect to built-in gain property contributed to it by U.S. persons (section 721(c) property). There are five requirements under the Gain Deferral Method:  First, the section 721(c) partnership is required to adopt the remedial allocation method for built-in gain with respect to section 721(c) property. The remedial method, which causes the contributing partner to recognize income in the same amount and at the same time as would occur had the contribution not been made, generally operates to eliminate any potential for shifting the tax burden associated with contributed property away from the contributing partner. The use of the remedial method is mandated even in instances where use of an alternative method would not 6 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | October 2015  Second, as long as there is any remaining built-in gain with respect to section 721(c) property, the section 721(c) partnership is required to allocate all items of section 704(b) income, gain, loss and deduction with respect to the section 721(c) property in the same proportion.

It seems clear that the rule was intended to prevent partners from unravelling the impact of remedial allocations through special allocations that might otherwise be respected. That is, to the extent the partnership has section 721(c) property, there will no longer be any ability to “specially” allocate income and loss among the partners with respect to that property. Otherwise, the notice provides little guidance with respect to interpretation of this mandate.

For example, it is not clear how this rule would apply to preferred partnership interests when the allocation scheme is designed to protect preferred capital.  Third, if the section 721(c) partnership is a foreign partnership, a U.S. transferor must comply with the reporting requirements imposed under sections 6038, 6038B, and 6046A. Form 8865 (Return of U.S.

Persons With Respect to Certain Foreign Partnerships) will be modified to include information with respect to contributions of section 721(c) property to section 721(c) partnerships.  Fourth, subject to certain exceptions, the U.S. transferor will recognize built-in gain with respect to section 721(c) property on the occurrence of an acceleration event (any transaction that would reduce the amount of remaining built-in gain that the U.S. transferor would recognize, a distribution of the built-in gain property to a person other than the U.S.