Description

JANUARY 2016

Table of Contents

4

New Partnership Audit Rules Impact

Both Existing and New Partnership and

LLC Operating Agreements

7

International Tax Disputes: A Ray of

Hope

9

The UK as a Tax-Efficient Holding

Company Jurisdiction

11

The Italian Patent Box and Its (Non-)

Compliance with OECD

Recommendations

Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of

2015—the Year-End Legislation f/k/a Extenders

Philip D. Morrison

Just in time for Christmas, Congress passed, with bipartisan support, and the

President signed, the “Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015” (PATH Act

or Act). The Act was part of an omnibus $1.1 trillion federal government funding bill.

Formerly known as the “extenders” bill, the PATH Act makes permanent several

perennially extended temporary tax provisions, extends some such provisions

through 2019, and extends the remainder through 2016. It also makes various tax

administrative/enforcement changes and makes important changes in the real estate

area related to REITs and to foreign investment in U.S.

real estate. A few tax provisions were also added to the omnibus funding bill outside the PATH Act. With the exception of a provision dealing with the issuance of Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs), a provision preventing the shifting of losses from a tax-indifferent (e.g., foreign) person to a U.S. taxpayer and a REIT provision described below, there were only minor revenue raisers in the package.

While the more important extenders and changes are summarized below, many narrow, miscellaneous provisions that were extended or made permanent are not discussed. A potentially important side effect of the PATH Act is how it changes the revenue baseline for future tax reform efforts. By making several expensive extenders permanent, it permanently reduces the 10-year revenue baseline against which future tax reform bills must be measured. Thus, in general, it should provide modestly greater flexibility in achieving revenue-neutral tax reform.

For example, a reform proposal to reduce the amount of the R&E credit now would raise revenue (rather than reduce it were the R&E credit still only temporary); the resulting revenue could be used for rate reduction. Boston Brussels Chicago Dallas Düsseldorf Frankfurt Houston London Los Angeles Miami Milan Munich New York Orange County Paris Rome Seoul Silicon Valley Washington, D.C. Strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices (Shanghai) . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS TAX PROVISIONS IN OMNIBUS BILL  Cadillac Tax: The bill provides for a two-year delay (from 2018 to 2020) in the excise tax enacted as part of Obamacare that is imposed on expensive employersponsored health plans (the Cadillac tax).  Health Insurance Provider Fee: The bill provides a oneyear moratorium on the Obamacare annual fee on health insurance providers.  Wind Energy: The bill extends (and extends the tapering of) the production tax credit and investment tax credit for wind energy facilities—from 80 percent to 60 percent to 40 percent, expiring after 2019 (as opposed to 2014).  Solar Energy: The bill extends (and extends the tapering of) the investment credit for solar energy installations. The phase out begins for projects begun in 2020 and the credit expires in 2022 (rather than 2016).  Internet Access Tax: The bill provides a one year extension of the ban on internet access taxes. PERMANENT EXTENDERS  Research Credit: The section 41 credit for research and experimentation is made permanent. Additionally, eligible small businesses (under $50 million gross receipts) may claim the credit against AMT. Even smaller businesses (under $5 million gross receipts) may claim the credit against employer FICA liability, subject to certain limits.  Subpart F Active Financing Income: The exclusion under section 954(h) is made permanent.

Thus, income derived in the active conduct of banking, financing, or similar businesses will continue to be excluded from the definition of foreign personal holding company income under Subpart F.  15-year cost recovery: The 15-year, straight-line cost recovery under section 168 for qualified leasehold improvements, qualified restaurant buildings and improvements, and qualified retail improvement property is made permanent.  Section 179: The increased expensing limitations under section 179 are made permanent. For 2014, the maximum amount a taxpayer could expense was $500,000 of the 2 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments cost of qualifying property placed in service in that year. That amount was reduced by the amount by which property placed in service in that year exceeded $2 million. Those amounts are made effective for 2015 under the Act and are indexed for inflation for 2016 and thereafter.

The Act also makes permanent the special rules that allow expensing for computer software and qualified real property, allows HVAC equipment placed in service after 2015 to qualify, and eliminates the $250,000 cap with respect to qualified real property.  RICs: The Act permanently extends the provisions allowing for pass-through to foreign investors of the character of interest-related dividends and short-term capital gain dividends from regulated investment companies. It also makes permanent the exclusion of regulated investment companies (RICs) from withholding under FIRPTA.  Small Business Stock: The 100 percent exclusion and exception from AMT for gains on the disposition of certain small business stock is made permanent. Among other requirements, the stock must not be owned by a corporation, must be acquired at original issue, and must be held for at least five years.  Child Tax Credit: The $1,000 child tax credit is refundable to the extent it exceeds the taxpayer’s tax liability limited by a formula.

The formula is 15 percent of earned income in excess of a threshold. The Act permanently sets the threshold at $3,000, rather than allowing it to return to $10,000 (indexed for inflation).  Secondary Education: The American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC) is made permanent. The $2,500 AOTC, a credit for up to four years of post-secondary education expenses, is phased out for higher incomes.  Earned Income Tax Credit: The Act makes permanent the recent temporary increases in the amount and income phase-out range of the EITC.  Employer-provided Transportation Benefits: The Act permanently extends the increased maximum monthly exclusion amount for mass transit passes and van pool .

FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS benefits to match the exclusion for qualified parking the adjusted basis of qualified property in 2018 and 30 benefits. percent in 2019. The Act revises the rules for interaction between bonus depreciation and the AMT and the rules  State and Local Sales Tax Deduction: The Act permanently extends the option to claim an itemized deduction for state and local sales taxes in lieu of an itemized deduction for state and local income taxes. A taxpayer may either deduct the actual amount of sales tax paid or, alternatively, deduct an amount prescribed by the IRS.  Charitable Contributions: The Act reinstates and makes permanent the increased percentage limits and extended carryforward for qualified conservation contributions for post-2014 contributions. The Act also makes permanent the ability to exclude from gross income qualified charitable contributions from IRAs, as well as other minor charitable contribution extenders. EXTENSIONS THROUGH 2019  New Markets Tax Credit: Section 45D provides a credit for certain investments in a qualified “community development entity” (entities providing investment capital for low-income persons or communities that are certified).

The Act extends the credit for five years, through 2019, and extends the carryforward for unused credits through 2024.  Work Opportunity Tax Credit: Section 51 and 52 provide a complex set of rules to calculate and claim a credit for certain first-year wages paid to new employees who are members of one of nine targeted groups. The targeted groups include certain veterans, ex-felons, certain disabled persons, and various other disadvantaged groups. The employer’s deduction for wages is reduced by the amount of the credit.

The Act extends the credit through 2019 and expands it to cover qualified long-term unemployment recipients.  Bonus Depreciation: Prior law allowed an additional first- dealing with orchards, groves and vineyards.  Look-through for Payments Between Related CFCs: Under section 954(c)(6), which sunset at the end of 2014, dividends, interest, rents and royalties received or accrued by a controlled foreign corporation “CFC” from a related CFC were not treated as foreign personal holding company income to the extent attributable or properly allocable to income of the payor that was neither subpart F income nor treated as effectively connected income of a US trade or business. The Act extends for five years the application of this rule, to taxable years of a CFC beginning before January 1, 2020, and to taxable years of U.S. shareholders of a CFC with or within which such CFC’s taxable year ends. EXTENSIONS THROUGH 2016 Among the 30 provisions extended through 2016 are:  Exclusion from gross income for discharge of indebtedness on principal residence;  Treatment of mortgage insurance premiums as qualified residence interest;  Above-the-line deduction for qualified tuition;  Classification of certain racehorses as three-year property;  Seven-year recovery period for motorsports entertainment complexes;  Deduction with respect to income attributable to domestic production activities in Puerto Rico;  Empowerment Zone tax incentives;  Moratorium of the Obamacare medical device excise tax; year depreciation deduction equal to 50 percent of the adjusted basis of qualified property placed in service prior to January 1, 2015.

The Act extends the bonus  Section 25C non-business energy property; depreciation provision for property acquired and placed in service during 2015 through 2019, but reduces the additional first year depreciation amount to 40 percent of  Various alternative energy and energy conservation  Incentives for biodiesel; and provisions. Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 3 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS PRINCIPAL REAL ESTATE-RELATED PROVISIONS  REIT Spin-offs: One of the largest of the very few revenue raisers in the Act is a provision restricting tax-free spinoffs involving Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITS). The provision provides that a spin-off involving a REIT will qualify as tax-free only if immediately after the transaction both the distributing and controlled corporations are REITs. The provision applies to distributions on or after December 7, 2015, unless a ruling request was submitted by that date.  Taxable REIT Subsidiaries: The current law limit of 25 percent on the value of REIT assets that may be stock of taxable REIT subsidiaries is lowered to 20 percent, effective for tax years beginning after 2017.  FIRPTA Exception for Certain Stock: The Act increases from 5 percent to 10 percent the maximum stock ownership a shareholder may hold in a publicly traded corporation to avoid having that stock treated as a U.S. real property interest when it is disposed of.  U.S. Real Property Interests Held by Foreign Pensions: The Act exempts the U.S.

real property interests held by foreign retirement and pension funds from FIRPTA withholding. TAX ADMINISTRATION AND ENFORCEMENT A variety of changes are implemented by the Act intended to reduce fraudulent claims of the EITC and other credits. In addition, the Act makes various relatively minor tax administration changes, many intended to deal with the IRS dealings with tax-exempt organizations. One such change permits section 501(c)(4) organizations to seek review in federal court of any revocation or denial of exempt status by the IRS.

Another makes modest technical corrections to the partnership audit rules enacted in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (discussed in the article that follows). Finally, the Act includes various provisions related to the Tax Court, including a provision stating that “the Tax Court is not an agency of, and shall be independent of, the executive branch,” and a provision specifying that the court use the general Federal Rules of Evidence (rather than the rules specific to the US District Court for the District of Columbia). 4 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 New Partnership Audit Rules Impact Both Existing and New Partnership and LLC Operating Agreements Thomas W. Giegerich, Gary C.

Karch, Kevin Spencer and Madeline Chiampou Tully On November 2, 2015, President Barack Obama signed the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (the Act) into law, instituting for tax years commencing after 2017 significant changes to the rules governing federal tax audits of entities that are treated as partnerships for U.S. federal income tax purposes. The new rules impose an entity-level liability for taxes on partnerships (and concomitantly, in the case of a general or limited partnership, the general partner) in respect of Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audit adjustments, absent election of an alternative regime described below under which the tax liability is imposed at the partner level.

The new rules constitute a significant change from existing law and will require clarification through guidance from the U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury). Certain small partnerships are eligible to elect out of the provisions altogether for a given taxable year, with the result that any adjustments to such a partnership’s items can be made only at the partner level. This election may be made only by partnerships with 100 or fewer partners, each of which is an individual, a C corporation, an S corporation or an estate of a deceased partner. Accordingly, for example, any partnership having another partnership as a partner is not eligible to elect out of the new audit regime. Under the new rules, in general, audit adjustment to items of partnership income, gain, loss, deduction or credit, and any partner’s distributive share thereof, are determined at the partnership level.

Subject to election of the alternative regime discussed below, the associated "imputed underpayment”— the tax deficiency arising from a partnership-level adjustment with respect to a partnership tax year (a reviewed year)—is calculated using the maximum statutory income tax rate and is assessed against and collected from the partnership in the year that such audit or any judicial review is completed (the . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS adjustment year). In addition, the partnership is directly liable by its actions in the audit. The IRS no longer will be required to for any related penalties and interest, calculated as if the partnership had been originally liable for the tax in the audited notify partners of partnership audit proceedings or adjustments, and partners will be bound by determinations year. made at the partnership level. It appears that partners neither will have rights to participate in partnership audits or related judicial proceedings, nor standing to bring a judicial action if The Act directs the Treasury to establish procedures under which the amount of the imputed underpayment may be modified in certain circumstances.

If one or more partners file tax returns for the reviewed year that take the audit adjustments into account and pay the associated taxes, the imputed underpayment amount should be determined without regard to the portion of the adjustments so taken into account. If the partnership demonstrates that a portion of the imputed underpayment is allocable to a partner that would not owe tax by reason of its status as a tax-exempt entity the procedures are to provide that the imputed underpayment is to be the partnership representative does not challenge an assessment. Partnerships challenging an assessment in a district court or the U.S. Court of Federal Claims will be required to deposit the entire amount of the partnership’s imputed liability (in contrast to existing rules that only require a deposit of the petitioning partner’s liability).

Also, the statute of limitations for adjustments will be calculated solely with reference to the date the partnership filed its return. As noted, the Act’s new partnership audit regime applies to tax determined without regard to that portion. The Act also directs that these procedures take into account reduced corporate, capital gain and qualified dividend rates as to the portion of returns filed for partnership taxable years beginning after December 31, 2017. The delayed effective date affords taxpayers time to consider the potential effects of the new any imputed underpayment allocable to a partner to which pertinent. rules on entities taxed as partnerships and their operative agreements and to evaluate options for addressing them. While the Act provides that a partnership may opt for the Act’s Under an alternative regime, if the partnership makes a timely amendments to the partnership audit rules to apply to any return of the partnership filed for taxable years beginning after the date of enactment of the Act, it is unlikely many election with respect to an imputed underpayment (a push-out election) and furnishes to each partner of the partnership for the reviewed year, and to the Treasury, a statement of the partner’s share of any adjustment to income, gain, loss, deduction or credit, the rules requiring partnership level assessment will not apply with respect to the underpayment and each affected partner will be required to take the adjustment into account on the partner’s individual tax return, and pay an increased tax, for the taxable year in which the partnerships will make such an election, at a minimum until such time as much needed Treasury guidance is produced. OPEN ISSUES Among the questions left unanswered for the moment are these: partner receives the adjusted information return.

Under this alternative, the reviewed year partners (rather than the 1. Are the elections such as the push-out election selfexecuting, or is there a need for an issuance of regulations partnership) are liable for any related penalties and interest, with deficiency interest calculated at an increased rate and running from the reviewed year. for such elections to be effective? The Act also institutes significant changes to procedural aspects of partnership audits. Among other things, the “tax matters partner” role under prior law is replaced with an has among its members a single-member limited liability company or a grantor trust? expanded “partnership representative” role.

The partnership representative, which is not required to be a partner, will have sole authority to act on behalf of the partnership in an audit small partnership exemption is unavailable): proceeding, and will bind both the partnership and the partners 2. Will the ability to elect out of these new rules under the small partnership exception be available if a partnership 3. In the absence of a push-out election (and assuming the A.

How do adjustments to income/deduction flow out to partners? Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 5 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS B. Since the associated tax will have been paid by the B. If the IRS appoints a partnership representative, does partnership already, by what mechanism do the partners avoid paying tax on the same income at the the appointee need to have some connection to the partnership? partner level? C. How do these rules work with items allocated by a partnership that are determined at the partner level? D.

If there is an item of income flowing from an IRS adjustment to the partners, do the partners increase their outside basis in their partnership interests to reflect their shares of the income? E. How does the IRS prevent gamesmanship in instances where there are significant shifts in partnership interests between the reviewed year and the adjustment year? F. How are the rules intended to work in the case of a constructive partnership? What if the constructive tax partnership does not constitute a state law partnership? Since there is no juridical entity, is nobody liable for the taxes flowing from the IRS adjustments? If the constructive partnership is a state law partnership (and therefore a general partnership) is each partner liable for the totality of the tax? Can a push-out election be made on a protective basis (i.e., without conceding to the existence of a partnership) in order to avoid such an outcome? Who would make it? G.

Are partners ultimately liable under any circumstances for adjustments, where the partnership is insolvent or otherwise cannot satisfy the adjustments (for example, C. Presumably appointees by the IRS can refuse the appointment; what can we expect to be the IRS' backup plan? POTENTIAL CONTRACTUAL PROVISIONS TO TAKE THE NEW RULES INTO ACCOUNT Set forth below are suggestions for the inclusion of provisions in partnership agreements in light of the new law. No single set of provisions can fit all circumstances, and, of course, the desirability of some of these provisions will depend on the partner's frame of reference; the partnership representative is going to have different objectives than is a minority partner, for example.

Possible contractual provisions include the following: 1. Use the small partnership exception, if available, and notify all partners of its election. A. Consider restricting eligible new partners to those that do not undercut the availability of this exception. B.

Consider prohibiting transfers that would terminate eligibility for the exception. 2. If the small partnership exception is not available, require the push-out election, and place contractual obligations on partners related thereto. Require partners to execute an acknowledgement and agreement that sets forth the import of the election. under transferee liability principles)? 3.

In the absence of a small partnership exception or pushH. What will be the state income tax consequences of federal audit adjustments? 4. If a push-out election is made: A.

Can partners take their loss carryovers and other tax attributes into account in calculating the associated tax? B. What happens if one or more partners do not pay the associated tax? Does the partnership have a residual exposure? 5. As to the appointment of a partnership representative: A.

Is it possible to replace a partnership representative once an audit has commenced? out election, agree on the economic sharing of partnershiplevel tax payments. For example: A. Provide that partnership-level tax payments in an adjustment year will be economically borne in proportion to the partners’ income in the reviewed year, taking into account characteristics of a partner that reduce the payment. B.

State whether partners’ shares of tax payments will be collected from them by current payment or by offset against distributions. C. Provide that departed or reduced interest partners agree to make payments for their shares of tax payments that cannot be offset against distributions. 6 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS D. Permit a holdback of distributions in the event of should consider including provisions such as those identified pending or expected tax audits. above. Moreover, a determination will need to be made as to whether existing partnership and LLC operating agreements E. Provide for the allocation of tax amounts that cannot be recovered from departed or reduced interest partners. 4.

Provide that the existing governance mechanisms of the partnership (whether managing partner or member, management committee or board) control tax decisions and the appointment, replacement and direction of the partnership representative. Authorize or require the partnership representative, acting at the direction of the board or other governing authority, to do some or all of the should be amended in light of the new rules and, if so, how and with what implications (for example, in terms of required consents). In the context of mergers and acquisitions, potential purchasers of partnership interests are likely to require that the partnership commit to make the push-out election in the event of an audit.

In short, the new partnership audit rules were enacted into law with little fanfare, and seemingly in short order, but with considerable consequences to the business community for years to come. following: A. Notify all partners upon the commencement of an IRS audit. B. Inform partners of the progress of the audit and consult with the partners before taking positions in response to proposed adjustments. C.

Resolve IRS audits in its sole discretion. Alternatively, condition authority on a certain level of partner consent and exonerate the partnership representative and the board from liability if the partnership representative proceeds on the basis of such consent. D. Require partners to provide the partnership representative timely partner-level information to mitigate partnership level tax. E. Secure partners' agreement to file amended returns at the partnership representative's request. F.

Make all elections and other decisions called for under the new rules in the exercise of its sole discretion. Alternatively, require the partnership representative to seek authorization for each such decision and action before taking it (perhaps on the basis of majority rule). CONCLUSION As the foregoing list demonstrates, it is not too early for affected taxpayers to start turning their attention to the practical steps they should be considering to address the implications of the new rules. Certainly, drafters of new partnership agreements and LLC operating agreements International Tax Disputes: A Ray of Hope Cym H.

Lowell and Todd Welty Despite the anticipated tsunami of tax disputes generated by underlying tensions in international taxation, there is reason for hope that appropriate means are being developed to address them efficiently and effectively. Multinational enterprises (MNEs) should be addressing their existing international taxation planning structures in light of coming changes in international tax regimes. This process is likely to be supervised at the board of directors level, reflecting the seriousness of events on the horizon. There exists today the unfortunate circumstance that longstanding, increasingly out-of-date treaty-based mutual agreement procedures (MAP) and domestic resolution processes are being overwhelmed by both the complexity and sheer volume of international tax disputes they are meant to, but are ill-equipped to, handle. The underlying tensions include:  Disputes over historic residence versus source country treaty and transfer pricing (TP) models;  Revenue collection from international businesses for all countries;  Base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) measures;  Competition between countries for MNE tax bases; Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 7 .

FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS  The desire of developing/source countries to address their own perceived needs;  The United Nations (UN) Secretariat’s focus on dispute resolution; of, for example, the UN membership, would provide a solid foundation for predictability. The following elements will be key to developing a successful ITDRP:  The needs of international financing organisations;  The perspectives of civil societies, and  The need on the part of MNEs to: 1) adapt global effective tax rate planning to the existing and evolving tax regimes of various countries and 2) anticipate means of handling disputes to minimize incidences of double taxation. As a result, countries are likely to devote additional resources to tax base protection. Each country needs the ability to  A thorough understanding of the obstacles to be overcome (including observations about sovereignty, cost, independence of arbitrators, control of process, scope creep, confidentiality and transparency);  The identification of the parties’ common objectives  A study of the experience of successful alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms in other areas; efficiently challenge tax planning that it believes provides insufficient tax revenue, including situations involving so-called double non-taxation. Inefficient dispute resolution processes  An approach that deals with the obstacles to the use of slow down the ability to resolve such challenges.  A broad consensus for the proposed approach; and In addition, MNEs are likely to focus on effective tax rate planning to take maximum advantage of competing tax  Implementation of the approach by an institution that has broad experience in administering cases through dispute resolution mechanisms in other contexts. regimes to minimize taxation and dangers of double taxation. The unpredictable nature of the BEPS process provides stark encouragement for MNEs to take the most aggressive arbitration in tax disputes, e.g., transparency versus confidentiality; STEPS FORWARD approaches possible, exploiting differences in various tax regimes while monitoring developments in international taxation and dispute resolution processes. On 5 October, the OECD released its final deliverables with Threats to the predictability of the tax base raise serious issues to taxing jurisdictions and MNEs alike. The only realistic antidote may be to create a dependable and independent Through the adoption of this Report, countries have agreed treaty-based international tax dispute resolution process (ITDRP) designed to accommodate the needs of all stakeholders.

While there may be broad dissatisfaction with standard with respect to the resolution of treaty-related disputes, committed to its rapid implementation and agreed to ensure its effective implementation through the the status quo, there is ample guidance in related areas of dispute resolution to provide light at the end of this tunnel. establishment of a robust peer-based monitoring mechanism that will report regularly through the Committee on Fiscal Affairs to the G20. The minimum standard will: WIRTSCHAFTS UNIVERSITY, VIENNA, JANUARY 2015 In a January 2015 meeting at Wirtschafts University, the attendees, as a group, began a process of developing a consensus on a way forward for dispute resolution in the international tax world. For an ITDRP to be meaningful for MNEs and countries alike, it will need to be embraced by as large a body as possible.

Acceptance by a unanimous action respect to BEPS, including Action 14. The following is an extract from the report (authors’ emphasis): to important changes in their approach to dispute resolution, in particular by having developed a minimum Ensure that treaty obligations related to the mutual agreement procedure are fully implemented in good faith and that MAP cases are resolved in a timely manner; Ensure the implementation of administrative processes that promote the prevention and timely resolution of treatyrelated disputes; and Ensure that taxpayers can access the MAP when eligible. 8 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS The minimum standard is complemented by a set of best A variety of concerns have, however, been raised for any type practices. The monitoring of the implementation of the minimum standard will be carried out pursuant to detailed of ADR for international tax purposes, including: terms of reference and an assessment methodology to be developed in the context of the OECD/G20 BEPS Project in 2016. In addition . .

. the following countries have declared  How to control the costs their commitment to provide for mandatory binding MAP arbitration in their bilateral tax treaties as a mechanism to guarantee that treaty-related disputes will be resolved within a specified timeframe: . .

. . This represents a major step forward as together these countries were involved in more than 90 percent of outstanding MAP cases at the end of 2013, as reported to the OECD.  Transparency, confidentiality and secrecy  Enforceability  Sovereignty  Inexperience of developing countries, independence of arbitrators and their selection within an arbitral institution  Procedural models for tax treaty arbitration  Parallelism in domestic remedies and due process An initial review of Action 14 suggests that it is intended to outline a normal OECD approach of model treaty guidelines  Arbitrability of taxes and monitoring.

Of course, this is the only option the OECD has in the absence of a capacity to actually administer a process on a global basis. Whether or not an OECD-led UN COMMITTEE process will be acceptable to a broad range of developing countries is an issue yet to be addressed. A paper on ITDRP was then released on October 8, 2015, by the Secretariat of the UN Commission of Experts in International Taxation (the UN Committee). It broadly reviewed all issues pertinent to the evolution of an effective tax dispute resolution process. When the OECD final Action 14 comments are read in conjunction with the UN Secretariat paper, it appears there is a natural link.

The OECD paper establishes a framework for ITDRP within the treaty MAP process, including eventual guidelines and monitoring. The UN paper seems to take over at this point by framing the need for a neutral administrator. What remains is the need for the development of an organization with broad experience in non-tax areas of dispute resolution to actually facilitate and administer a process. At the October 2015 meeting of the UN Committee in Geneva, there was broad, near unanimous support for the formation of a subcommittee to address ways of achieving ITDRP within the framework of the MAP provisions of global treaty networks. This is, frankly, a rather amazing evolution, as it reflects the coordinated efforts of developed and developing countries both within and outside the membership of the OECD to focus on this critical issue for all stakeholders in the international taxation world. The UK as a Tax-Efficient Holding Company Jurisdiction Matthew Herrington The UK is an attractive holding company jurisdiction for multinational groups looking to establish both interim UK holding companies within their existing groups, and holding companies for the group as a whole. ICC DISPUTE RESOLUTION The Taxation Commission of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), which has almost 100 years of experience in While there is no specific UK tax code for holding companies, the attractiveness of the United Kingdom as a holding all types of state-to-state, commercial, investment and other forms of dispute resolution, has made enhanced taxation dispute resolution mechanisms a priority for the global company regime is largely attributable to the recent overhaul of the country’s approach to the taxation of foreign profits and a low headline rate of corporate income tax. business community, working in cooperation with the OECD and UN. Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 9 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS The specific aspects of the UK tax code that make the United  A relatively extensive system for obtaining non-statutory Kingdom an attractive regime for a holding company include: and statutory clearances, as well as the facility to negotiate advance pricing agreements and advance thin  A low headline rate of corporate income tax (20 percent) capitalisation agreements for transfer pricing purposes; and that is projected to fall to 19 percent in 2017 and to 18 percent in 2020;  A territorial system of corporate taxation that involves an exemption for profits of foreign permanent establishments. In addition, a disposal of shares in a UK holding company by an offshore shareholder will not generally be subject to UK tax;  A common system for the taxation of domestic and foreign-source dividends. Most dividends received by a UK holding company will not be subject to corporation tax, regardless of their source;  A domestic participation exemption for capital gains realised on the disposal of substantial shareholdings in trading companies (or holding companies of trading groups) that have been held for at least 12 months;  The absence of UK withholding tax on outbound dividends, which applies regardless of the jurisdiction of residence of the recipient. There is no requirement for the recipient to be the beneficial owner in order for the withholding tax exemption to apply;  The availability of an extensive network of double taxation treaties to reduce UK withholding tax on interest and royalties;  A generous regime for tax relief on interest payments. In general, the United Kingdom gives relief for tax purposes in line with the accounting treatment of the interest, for example, on an accruals basis over the life of the loan;  Membership in the European Union, which brings the benefit of access to legislation such as the ParentSubsidiary Directive and the Interest and Royalties Directive;  A new controlled foreign company code that supports the general approach to territoriality (by focusing only on profits that have been artificially diverted from the United Kingdom) and enables a UK holding company to locate a group finance subsidiary offshore and be taxed at an effective rate of only 5 percent on interest income notionally attributed to the United Kingdom; 10 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016  The existence of a wide range of targeted incentives aimed at encouraging and supporting growth in certain sectors, including the UK patent box regime and regimes that support research and development. The UK tax authorities are also generally oriented to be helpful, with customer relationship managers for large businesses, a generally good understanding of multinational business and support for inward investment into the United Kingdom. The potential downsides of locating a holding company in the United Kingdom include:  The potential for exit charges on certain assets and shares leaving the UK tax net.

In practice, however, this can often be addressed by relying on a relief, such as the domestic participation exemption for share sales;  The sale of shares in a UK company still attracts a charge to transfer taxes (stamp duty and stamp duty reserve tax) at the rate of 0.5 percent of the consideration given by the purchaser of the shares;  The United Kingdom is currently consulting on the implementation of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) recommendations on restricting interest deductibility in line with a fixed earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization ratio (or a fixed group ratio). There are also several existing domestic rules that can restrict interest deductibility such as transfer pricing, “purpose” rules, the worldwide debt cap, the antiarbitrage rules and the distributions regime;  UK tax legislation is long and complex, and contains a number of anti-avoidance rules (including a domestic General Anti-Abuse Rule) that always have to be considered even in relation to entirely commercial arrangements; and  The United Kingdom has recently introduced a new “diverted profits tax” under Action 7 of the OECD’s BEPS Project, which is intended to counter diversion of profits . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS from the United Kingdom through aggressive tax planning in many other EU countries. The Italian regime is relevant for techniques. both Corporate Income Tax (IRES, at 27.5 percent) and the Regional Tax on Productive Activities (IRAP, ordinary rate at Overall however, the United Kingdom is a very attractive holding company jurisdiction and has a highly competitive tax package to offer as an “onshore” prospect. The Italian Patent Box and Its (Non-) Compliance with OECD Recommendations Carlo Maria Paolella and Federico Bortolameazzi The Italian Patent Box regime largely complies with the OECD recommendations to prevent base erosion and profit shifting. Its non-compliant features offer a brief window of opportunity for companies able to take swift advantage of its wide range of qualifying intangible assets. 3.9 percent). The enactment of this regime took place while the OECD was developing the Report on Action 5 and delivering interim discussion drafts. As a result, the Italian Patent Box is already widely aligned with the principles defined by the OECD. The Italian Patent Box is a very attractive regime. It provides a 50 percent exemption (30 percent in 2015, 40 percent in 2016) on income derived from the exploitation of a wide range of qualifying intangible assets, after the application of a specific ratio based on the costs borne for the development, acquisition, enhancement and maintenance of those intangibles.

The incentive is determined according to a proscribed formula (see box). Many countries have implemented specific IP regimes through their domestic tax legislation that provide a tax benefit for income derived from intangible assets such as patents and designs. Although these regimes generally are regarded positively as tools to incentivize research and innovation, they also have been criticized on the basis they are designed by Furthermore, the Patent Box grants a full exemption from taxation for capital gains arising from the sale of the qualifying many countries in a way that generates harmful tax competition between tax jurisdictions. intangible assets. The sole condition is that 90 percent of the consideration obtained from the sale is re-invested in the maintenance, enhancement or development of other qualifying As a result, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and intangible assets. Development (OECD) has explicitly addressed these regimes in the context of the implementation of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Action Plan.

The BEPS Action Plan has The Patent Box regime is optional and requires a five year irrevocable opt-in. been developed with the support of the G20 in order to tackle international tax avoidance by enterprises with a broad international consensus. The “Report on Action 5, Countering harmful tax practices more effectively, taking into account transparency and substance,” delivered on October 5, 2015, defined the SCOPE OF APPLICATION In theory, any taxpayer carrying out a business activity in Italy, either as a tax resident or through a permanent establishment located in the country, is eligible for the regime. The sole requirement is, however, a substantial one: the taxpayer must features of IP regimes that can be regarded as non-harmful. be undertaking a qualifying research activity that leads to the creation of a qualifying IP asset. If only non-qualifying research is carried out, or no qualifying IP is obtained, no benefit is At the end of 2014, the Italian Parliament approved the Budget Law for 2015 which, inter alia, introduced for the first time in granted. Italy a Patent Box tax regime, similar to those already in place Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 11 .

FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS The true strength of the regime resides in the wide range of More complex calculations are required when the IP is intangibles that qualify: exploited internally. The use of transfer pricing methods is required to provide a reliable calculation of the portion of  Industrial patents, biotech inventions, utility models, patents income internally generated that can be attributed to the IP. In these circumstances, the determination of the eligible income has to be granted through an advance ruling by the Italian for plant varieties and designs for semiconductors;  Business, commercial, industrial, and scientific information and know-how that can be held as secret and the protection of which can be legally enforced;  Formulas and processes;  Legally protected designs and models;  Software protected by copyright; and  Trademarks, including collective trademarks, either registered or in the process of registration. Agency of Revenue, which can be fairly time consuming. It is likely that the agency will see an increase in requests for rulings under the new regime, which will undoubtedly slow the process further.

For this reason, while the tax benefit can only be taken after the ruling is granted, the benefit will be retroactive to the fiscal year in which the ruling request is filed. This is why filing during 2015 was recommended for companies wishing to fully exploit the benefits of the Patent Box. CALCULATING THE COSTS In compliance with the guidelines developed by the OECD, it is necessary to apply a formula to the identified IP income. The formula considers all the costs borne in order to acquire, develop or maintain the IP in order to reduce (or rule out) the tax incentive when the taxpayer bears the following nonqualifying costs (tainted costs) related to the intangible asset:  Research and development costs outsourced to companies or other entities belonging to the same group of the taxpayer.  Costs of acquiring the intangible from related or unrelated third parties. The formula is as follows: NON-COMPLIANT FEATURES It is the broad scope of the eligible intangibles that makes the Italian Patent Box non-compliant with the OECD principles. The OECD has explicitly stated that marketing intangibles cannot qualify for IP regimes, but the Italian Patent Box includes trademarks. Furthermore, the OECD Report has stated that intangibles, other than patents and copyrighted software, can be eligible only:  To smaller taxpayers (basically, small-and medium-sized enterprises, with €50 million overall turnover and €7.5 million of turnover attributable to the intangible);  If the relevant intangible is certified by a public agency (other than the tax administration); and  The denominator includes all the costs incurred by the taxpayer for the purpose of acquiring, developing and maintaining the relevant IP.  If the relevant intangible is non-obvious, useful and novel.  The numerator includes the same kind of costs included within the denominator, but the tainted costs are computed only up to an amount equal to 30 percent of the other be included in a fully compliant regime. qualifying costs. INCOME DERIVED FROM THE IP ASSET The calculation of the income that can be imputed to the IP can be relatively simple when the intangible is licensed to third parties, since the royalty paid to the IP holder by the licensee constitutes the primary item to be considered. 12 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 The last requirement also gives rise to the question of whether or not even designs and models, other than utility models, can The OECD has, however, also defined some transitional rules (and some anti-avoidance rules) in order to allow EU Member States to amend their domestic legislation in accordance with these principles. The OECD has stated that non-compliant regimes must be repealed by June 30, 2021.

It has also declared a ban on “new entrants” to existing non-compliant regimes, stating that no . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS new opt-ins are allowed after June 30, 2016. As a consequence, taxpayers currently have a one-off, brief opportunity to benefit from the Italian Patent Box in relation to their trademarks, know-how (for large enterprises) and possibly even models. If they are willing to take this opportunity, they must opt-in by June 30, 2016. EDITOR For more information, please contact your regular McDermott lawyer, or: Thomas W. Giegerich Partner-in-Charge, New York Tax Practice +1 212 547 5335 tgiegerich@mwe.com For more information about McDermott Will & Emery visit www.mwe.com The material in this publication may not be reproduced, in whole or part without acknowledgement of its source and copyright.

Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments is intended to provide information of general interest in a summary manner and should not be construed as individual legal advice. Readers should consult with their McDermott Will & Emery lawyer or other professional counsel before acting on the information contained in this publication. ©2016 McDermott Will & Emery. The following legal entities are collectively referred to as “McDermott Will & Emery,” “McDermott” or “the Firm”: McDermott Will & Emery LLP, McDermott Will & Emery AARPI, McDermott Will & Emery Belgium LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Rechtsanwälte Steuerberater LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Studio Legale Associato and McDermott Will & Emery UK LLP.

These entities coordinate their activities through service agreements. McDermott has a strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices, a separate law firm. This communication may be considered attorney advertising. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 13 .

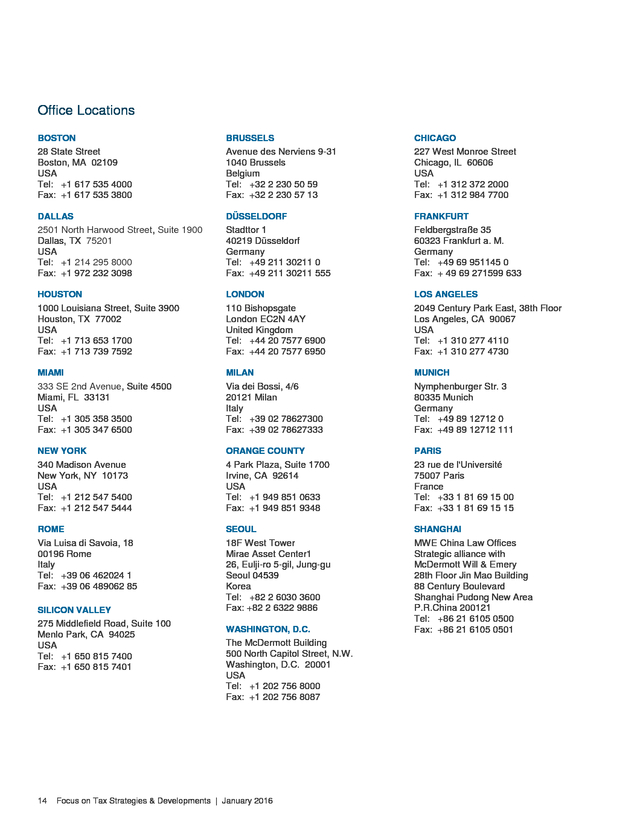

Office Locations BOSTON BRUSSELS CHICAGO 28 State Street Boston, MA 02109 USA Tel: +1 617 535 4000 Fax: +1 617 535 3800 Avenue des Nerviens 9-31 1040 Brussels Belgium Tel: +32 2 230 50 59 Fax: +32 2 230 57 13 227 West Monroe Street Chicago, IL 60606 USA Tel: +1 312 372 2000 Fax: +1 312 984 7700 DALLAS DÜSSELDORF FRANKFURT 2501 North Harwood Street, Suite 1900 Dallas, TX 75201 USA Tel: +1 214 295 8000 Fax: +1 972 232 3098 Stadttor 1 40219 Düsseldorf Germany Tel: +49 211 30211 0 Fax: +49 211 30211 555 Feldbergstraße 35 60323 Frankfurt a. M. Germany Tel: +49 69 951145 0 Fax: + 49 69 271599 633 HOUSTON LONDON LOS ANGELES 1000 Louisiana Street, Suite 3900 Houston, TX 77002 USA Tel: +1 713 653 1700 Fax: +1 713 739 7592 110 Bishopsgate London EC2N 4AY United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7577 6900 Fax: +44 20 7577 6950 2049 Century Park East, 38th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90067 USA Tel: +1 310 277 4110 Fax: +1 310 277 4730 MIAMI MILAN MUNICH 333 SE 2nd Avenue, Suite 4500 Miami, FL 33131 USA Tel: +1 305 358 3500 Fax: +1 305 347 6500 Via dei Bossi, 4/6 20121 Milan Italy Tel: +39 02 78627300 Fax: +39 02 78627333 Nymphenburger Str. 3 80335 Munich Germany Tel: +49 89 12712 0 Fax: +49 89 12712 111 NEW YORK ORANGE COUNTY PARIS 340 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10173 USA Tel: +1 212 547 5400 Fax: +1 212 547 5444 4 Park Plaza, Suite 1700 Irvine, CA 92614 USA Tel: +1 949 851 0633 Fax: +1 949 851 9348 23 rue de l'Université 75007 Paris France Tel: +33 1 81 69 15 00 Fax: +33 1 81 69 15 15 ROME SEOUL SHANGHAI Via Luisa di Savoia, 18 00196 Rome Italy Tel: +39 06 462024 1 Fax: +39 06 489062 85 18F West Tower Mirae Asset Center1 26, Eulji-ro 5-gil, Jung-gu Seoul 04539 Korea Tel: +82 2 6030 3600 Fax: +82 2 6322 9886 MWE China Law Offices Strategic alliance with McDermott Will & Emery 28th Floor Jin Mao Building 88 Century Boulevard Shanghai Pudong New Area P.R.China 200121 Tel: +86 21 6105 0500 Fax: +86 21 6105 0501 SILICON VALLEY 275 Middlefield Road, Suite 100 Menlo Park, CA 94025 USA Tel: +1 650 815 7400 Fax: +1 650 815 7401 14 WASHINGTON, D.C. The McDermott Building 500 North Capitol Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 USA Tel: +1 202 756 8000 Fax: +1 202 756 8087 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 .

real estate. A few tax provisions were also added to the omnibus funding bill outside the PATH Act. With the exception of a provision dealing with the issuance of Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs), a provision preventing the shifting of losses from a tax-indifferent (e.g., foreign) person to a U.S. taxpayer and a REIT provision described below, there were only minor revenue raisers in the package.

While the more important extenders and changes are summarized below, many narrow, miscellaneous provisions that were extended or made permanent are not discussed. A potentially important side effect of the PATH Act is how it changes the revenue baseline for future tax reform efforts. By making several expensive extenders permanent, it permanently reduces the 10-year revenue baseline against which future tax reform bills must be measured. Thus, in general, it should provide modestly greater flexibility in achieving revenue-neutral tax reform.

For example, a reform proposal to reduce the amount of the R&E credit now would raise revenue (rather than reduce it were the R&E credit still only temporary); the resulting revenue could be used for rate reduction. Boston Brussels Chicago Dallas Düsseldorf Frankfurt Houston London Los Angeles Miami Milan Munich New York Orange County Paris Rome Seoul Silicon Valley Washington, D.C. Strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices (Shanghai) . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS TAX PROVISIONS IN OMNIBUS BILL  Cadillac Tax: The bill provides for a two-year delay (from 2018 to 2020) in the excise tax enacted as part of Obamacare that is imposed on expensive employersponsored health plans (the Cadillac tax).  Health Insurance Provider Fee: The bill provides a oneyear moratorium on the Obamacare annual fee on health insurance providers.  Wind Energy: The bill extends (and extends the tapering of) the production tax credit and investment tax credit for wind energy facilities—from 80 percent to 60 percent to 40 percent, expiring after 2019 (as opposed to 2014).  Solar Energy: The bill extends (and extends the tapering of) the investment credit for solar energy installations. The phase out begins for projects begun in 2020 and the credit expires in 2022 (rather than 2016).  Internet Access Tax: The bill provides a one year extension of the ban on internet access taxes. PERMANENT EXTENDERS  Research Credit: The section 41 credit for research and experimentation is made permanent. Additionally, eligible small businesses (under $50 million gross receipts) may claim the credit against AMT. Even smaller businesses (under $5 million gross receipts) may claim the credit against employer FICA liability, subject to certain limits.  Subpart F Active Financing Income: The exclusion under section 954(h) is made permanent.

Thus, income derived in the active conduct of banking, financing, or similar businesses will continue to be excluded from the definition of foreign personal holding company income under Subpart F.  15-year cost recovery: The 15-year, straight-line cost recovery under section 168 for qualified leasehold improvements, qualified restaurant buildings and improvements, and qualified retail improvement property is made permanent.  Section 179: The increased expensing limitations under section 179 are made permanent. For 2014, the maximum amount a taxpayer could expense was $500,000 of the 2 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments cost of qualifying property placed in service in that year. That amount was reduced by the amount by which property placed in service in that year exceeded $2 million. Those amounts are made effective for 2015 under the Act and are indexed for inflation for 2016 and thereafter.

The Act also makes permanent the special rules that allow expensing for computer software and qualified real property, allows HVAC equipment placed in service after 2015 to qualify, and eliminates the $250,000 cap with respect to qualified real property.  RICs: The Act permanently extends the provisions allowing for pass-through to foreign investors of the character of interest-related dividends and short-term capital gain dividends from regulated investment companies. It also makes permanent the exclusion of regulated investment companies (RICs) from withholding under FIRPTA.  Small Business Stock: The 100 percent exclusion and exception from AMT for gains on the disposition of certain small business stock is made permanent. Among other requirements, the stock must not be owned by a corporation, must be acquired at original issue, and must be held for at least five years.  Child Tax Credit: The $1,000 child tax credit is refundable to the extent it exceeds the taxpayer’s tax liability limited by a formula.

The formula is 15 percent of earned income in excess of a threshold. The Act permanently sets the threshold at $3,000, rather than allowing it to return to $10,000 (indexed for inflation).  Secondary Education: The American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC) is made permanent. The $2,500 AOTC, a credit for up to four years of post-secondary education expenses, is phased out for higher incomes.  Earned Income Tax Credit: The Act makes permanent the recent temporary increases in the amount and income phase-out range of the EITC.  Employer-provided Transportation Benefits: The Act permanently extends the increased maximum monthly exclusion amount for mass transit passes and van pool .

FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS benefits to match the exclusion for qualified parking the adjusted basis of qualified property in 2018 and 30 benefits. percent in 2019. The Act revises the rules for interaction between bonus depreciation and the AMT and the rules  State and Local Sales Tax Deduction: The Act permanently extends the option to claim an itemized deduction for state and local sales taxes in lieu of an itemized deduction for state and local income taxes. A taxpayer may either deduct the actual amount of sales tax paid or, alternatively, deduct an amount prescribed by the IRS.  Charitable Contributions: The Act reinstates and makes permanent the increased percentage limits and extended carryforward for qualified conservation contributions for post-2014 contributions. The Act also makes permanent the ability to exclude from gross income qualified charitable contributions from IRAs, as well as other minor charitable contribution extenders. EXTENSIONS THROUGH 2019  New Markets Tax Credit: Section 45D provides a credit for certain investments in a qualified “community development entity” (entities providing investment capital for low-income persons or communities that are certified).

The Act extends the credit for five years, through 2019, and extends the carryforward for unused credits through 2024.  Work Opportunity Tax Credit: Section 51 and 52 provide a complex set of rules to calculate and claim a credit for certain first-year wages paid to new employees who are members of one of nine targeted groups. The targeted groups include certain veterans, ex-felons, certain disabled persons, and various other disadvantaged groups. The employer’s deduction for wages is reduced by the amount of the credit.

The Act extends the credit through 2019 and expands it to cover qualified long-term unemployment recipients.  Bonus Depreciation: Prior law allowed an additional first- dealing with orchards, groves and vineyards.  Look-through for Payments Between Related CFCs: Under section 954(c)(6), which sunset at the end of 2014, dividends, interest, rents and royalties received or accrued by a controlled foreign corporation “CFC” from a related CFC were not treated as foreign personal holding company income to the extent attributable or properly allocable to income of the payor that was neither subpart F income nor treated as effectively connected income of a US trade or business. The Act extends for five years the application of this rule, to taxable years of a CFC beginning before January 1, 2020, and to taxable years of U.S. shareholders of a CFC with or within which such CFC’s taxable year ends. EXTENSIONS THROUGH 2016 Among the 30 provisions extended through 2016 are:  Exclusion from gross income for discharge of indebtedness on principal residence;  Treatment of mortgage insurance premiums as qualified residence interest;  Above-the-line deduction for qualified tuition;  Classification of certain racehorses as three-year property;  Seven-year recovery period for motorsports entertainment complexes;  Deduction with respect to income attributable to domestic production activities in Puerto Rico;  Empowerment Zone tax incentives;  Moratorium of the Obamacare medical device excise tax; year depreciation deduction equal to 50 percent of the adjusted basis of qualified property placed in service prior to January 1, 2015.

The Act extends the bonus  Section 25C non-business energy property; depreciation provision for property acquired and placed in service during 2015 through 2019, but reduces the additional first year depreciation amount to 40 percent of  Various alternative energy and energy conservation  Incentives for biodiesel; and provisions. Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 3 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS PRINCIPAL REAL ESTATE-RELATED PROVISIONS  REIT Spin-offs: One of the largest of the very few revenue raisers in the Act is a provision restricting tax-free spinoffs involving Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITS). The provision provides that a spin-off involving a REIT will qualify as tax-free only if immediately after the transaction both the distributing and controlled corporations are REITs. The provision applies to distributions on or after December 7, 2015, unless a ruling request was submitted by that date.  Taxable REIT Subsidiaries: The current law limit of 25 percent on the value of REIT assets that may be stock of taxable REIT subsidiaries is lowered to 20 percent, effective for tax years beginning after 2017.  FIRPTA Exception for Certain Stock: The Act increases from 5 percent to 10 percent the maximum stock ownership a shareholder may hold in a publicly traded corporation to avoid having that stock treated as a U.S. real property interest when it is disposed of.  U.S. Real Property Interests Held by Foreign Pensions: The Act exempts the U.S.

real property interests held by foreign retirement and pension funds from FIRPTA withholding. TAX ADMINISTRATION AND ENFORCEMENT A variety of changes are implemented by the Act intended to reduce fraudulent claims of the EITC and other credits. In addition, the Act makes various relatively minor tax administration changes, many intended to deal with the IRS dealings with tax-exempt organizations. One such change permits section 501(c)(4) organizations to seek review in federal court of any revocation or denial of exempt status by the IRS.

Another makes modest technical corrections to the partnership audit rules enacted in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (discussed in the article that follows). Finally, the Act includes various provisions related to the Tax Court, including a provision stating that “the Tax Court is not an agency of, and shall be independent of, the executive branch,” and a provision specifying that the court use the general Federal Rules of Evidence (rather than the rules specific to the US District Court for the District of Columbia). 4 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 New Partnership Audit Rules Impact Both Existing and New Partnership and LLC Operating Agreements Thomas W. Giegerich, Gary C.

Karch, Kevin Spencer and Madeline Chiampou Tully On November 2, 2015, President Barack Obama signed the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (the Act) into law, instituting for tax years commencing after 2017 significant changes to the rules governing federal tax audits of entities that are treated as partnerships for U.S. federal income tax purposes. The new rules impose an entity-level liability for taxes on partnerships (and concomitantly, in the case of a general or limited partnership, the general partner) in respect of Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audit adjustments, absent election of an alternative regime described below under which the tax liability is imposed at the partner level.

The new rules constitute a significant change from existing law and will require clarification through guidance from the U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury). Certain small partnerships are eligible to elect out of the provisions altogether for a given taxable year, with the result that any adjustments to such a partnership’s items can be made only at the partner level. This election may be made only by partnerships with 100 or fewer partners, each of which is an individual, a C corporation, an S corporation or an estate of a deceased partner. Accordingly, for example, any partnership having another partnership as a partner is not eligible to elect out of the new audit regime. Under the new rules, in general, audit adjustment to items of partnership income, gain, loss, deduction or credit, and any partner’s distributive share thereof, are determined at the partnership level.

Subject to election of the alternative regime discussed below, the associated "imputed underpayment”— the tax deficiency arising from a partnership-level adjustment with respect to a partnership tax year (a reviewed year)—is calculated using the maximum statutory income tax rate and is assessed against and collected from the partnership in the year that such audit or any judicial review is completed (the . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS adjustment year). In addition, the partnership is directly liable by its actions in the audit. The IRS no longer will be required to for any related penalties and interest, calculated as if the partnership had been originally liable for the tax in the audited notify partners of partnership audit proceedings or adjustments, and partners will be bound by determinations year. made at the partnership level. It appears that partners neither will have rights to participate in partnership audits or related judicial proceedings, nor standing to bring a judicial action if The Act directs the Treasury to establish procedures under which the amount of the imputed underpayment may be modified in certain circumstances.

If one or more partners file tax returns for the reviewed year that take the audit adjustments into account and pay the associated taxes, the imputed underpayment amount should be determined without regard to the portion of the adjustments so taken into account. If the partnership demonstrates that a portion of the imputed underpayment is allocable to a partner that would not owe tax by reason of its status as a tax-exempt entity the procedures are to provide that the imputed underpayment is to be the partnership representative does not challenge an assessment. Partnerships challenging an assessment in a district court or the U.S. Court of Federal Claims will be required to deposit the entire amount of the partnership’s imputed liability (in contrast to existing rules that only require a deposit of the petitioning partner’s liability).

Also, the statute of limitations for adjustments will be calculated solely with reference to the date the partnership filed its return. As noted, the Act’s new partnership audit regime applies to tax determined without regard to that portion. The Act also directs that these procedures take into account reduced corporate, capital gain and qualified dividend rates as to the portion of returns filed for partnership taxable years beginning after December 31, 2017. The delayed effective date affords taxpayers time to consider the potential effects of the new any imputed underpayment allocable to a partner to which pertinent. rules on entities taxed as partnerships and their operative agreements and to evaluate options for addressing them. While the Act provides that a partnership may opt for the Act’s Under an alternative regime, if the partnership makes a timely amendments to the partnership audit rules to apply to any return of the partnership filed for taxable years beginning after the date of enactment of the Act, it is unlikely many election with respect to an imputed underpayment (a push-out election) and furnishes to each partner of the partnership for the reviewed year, and to the Treasury, a statement of the partner’s share of any adjustment to income, gain, loss, deduction or credit, the rules requiring partnership level assessment will not apply with respect to the underpayment and each affected partner will be required to take the adjustment into account on the partner’s individual tax return, and pay an increased tax, for the taxable year in which the partnerships will make such an election, at a minimum until such time as much needed Treasury guidance is produced. OPEN ISSUES Among the questions left unanswered for the moment are these: partner receives the adjusted information return.

Under this alternative, the reviewed year partners (rather than the 1. Are the elections such as the push-out election selfexecuting, or is there a need for an issuance of regulations partnership) are liable for any related penalties and interest, with deficiency interest calculated at an increased rate and running from the reviewed year. for such elections to be effective? The Act also institutes significant changes to procedural aspects of partnership audits. Among other things, the “tax matters partner” role under prior law is replaced with an has among its members a single-member limited liability company or a grantor trust? expanded “partnership representative” role.

The partnership representative, which is not required to be a partner, will have sole authority to act on behalf of the partnership in an audit small partnership exemption is unavailable): proceeding, and will bind both the partnership and the partners 2. Will the ability to elect out of these new rules under the small partnership exception be available if a partnership 3. In the absence of a push-out election (and assuming the A.

How do adjustments to income/deduction flow out to partners? Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 5 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS B. Since the associated tax will have been paid by the B. If the IRS appoints a partnership representative, does partnership already, by what mechanism do the partners avoid paying tax on the same income at the the appointee need to have some connection to the partnership? partner level? C. How do these rules work with items allocated by a partnership that are determined at the partner level? D.

If there is an item of income flowing from an IRS adjustment to the partners, do the partners increase their outside basis in their partnership interests to reflect their shares of the income? E. How does the IRS prevent gamesmanship in instances where there are significant shifts in partnership interests between the reviewed year and the adjustment year? F. How are the rules intended to work in the case of a constructive partnership? What if the constructive tax partnership does not constitute a state law partnership? Since there is no juridical entity, is nobody liable for the taxes flowing from the IRS adjustments? If the constructive partnership is a state law partnership (and therefore a general partnership) is each partner liable for the totality of the tax? Can a push-out election be made on a protective basis (i.e., without conceding to the existence of a partnership) in order to avoid such an outcome? Who would make it? G.

Are partners ultimately liable under any circumstances for adjustments, where the partnership is insolvent or otherwise cannot satisfy the adjustments (for example, C. Presumably appointees by the IRS can refuse the appointment; what can we expect to be the IRS' backup plan? POTENTIAL CONTRACTUAL PROVISIONS TO TAKE THE NEW RULES INTO ACCOUNT Set forth below are suggestions for the inclusion of provisions in partnership agreements in light of the new law. No single set of provisions can fit all circumstances, and, of course, the desirability of some of these provisions will depend on the partner's frame of reference; the partnership representative is going to have different objectives than is a minority partner, for example.

Possible contractual provisions include the following: 1. Use the small partnership exception, if available, and notify all partners of its election. A. Consider restricting eligible new partners to those that do not undercut the availability of this exception. B.

Consider prohibiting transfers that would terminate eligibility for the exception. 2. If the small partnership exception is not available, require the push-out election, and place contractual obligations on partners related thereto. Require partners to execute an acknowledgement and agreement that sets forth the import of the election. under transferee liability principles)? 3.

In the absence of a small partnership exception or pushH. What will be the state income tax consequences of federal audit adjustments? 4. If a push-out election is made: A.

Can partners take their loss carryovers and other tax attributes into account in calculating the associated tax? B. What happens if one or more partners do not pay the associated tax? Does the partnership have a residual exposure? 5. As to the appointment of a partnership representative: A.

Is it possible to replace a partnership representative once an audit has commenced? out election, agree on the economic sharing of partnershiplevel tax payments. For example: A. Provide that partnership-level tax payments in an adjustment year will be economically borne in proportion to the partners’ income in the reviewed year, taking into account characteristics of a partner that reduce the payment. B.

State whether partners’ shares of tax payments will be collected from them by current payment or by offset against distributions. C. Provide that departed or reduced interest partners agree to make payments for their shares of tax payments that cannot be offset against distributions. 6 Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 . FOCUS ON TAX STRATEGIES & DEVELOPMENTS D. Permit a holdback of distributions in the event of should consider including provisions such as those identified pending or expected tax audits. above. Moreover, a determination will need to be made as to whether existing partnership and LLC operating agreements E. Provide for the allocation of tax amounts that cannot be recovered from departed or reduced interest partners. 4.

Provide that the existing governance mechanisms of the partnership (whether managing partner or member, management committee or board) control tax decisions and the appointment, replacement and direction of the partnership representative. Authorize or require the partnership representative, acting at the direction of the board or other governing authority, to do some or all of the should be amended in light of the new rules and, if so, how and with what implications (for example, in terms of required consents). In the context of mergers and acquisitions, potential purchasers of partnership interests are likely to require that the partnership commit to make the push-out election in the event of an audit.

In short, the new partnership audit rules were enacted into law with little fanfare, and seemingly in short order, but with considerable consequences to the business community for years to come. following: A. Notify all partners upon the commencement of an IRS audit. B. Inform partners of the progress of the audit and consult with the partners before taking positions in response to proposed adjustments. C.

Resolve IRS audits in its sole discretion. Alternatively, condition authority on a certain level of partner consent and exonerate the partnership representative and the board from liability if the partnership representative proceeds on the basis of such consent. D. Require partners to provide the partnership representative timely partner-level information to mitigate partnership level tax. E. Secure partners' agreement to file amended returns at the partnership representative's request. F.

Make all elections and other decisions called for under the new rules in the exercise of its sole discretion. Alternatively, require the partnership representative to seek authorization for each such decision and action before taking it (perhaps on the basis of majority rule). CONCLUSION As the foregoing list demonstrates, it is not too early for affected taxpayers to start turning their attention to the practical steps they should be considering to address the implications of the new rules. Certainly, drafters of new partnership agreements and LLC operating agreements International Tax Disputes: A Ray of Hope Cym H.

Lowell and Todd Welty Despite the anticipated tsunami of tax disputes generated by underlying tensions in international taxation, there is reason for hope that appropriate means are being developed to address them efficiently and effectively. Multinational enterprises (MNEs) should be addressing their existing international taxation planning structures in light of coming changes in international tax regimes. This process is likely to be supervised at the board of directors level, reflecting the seriousness of events on the horizon. There exists today the unfortunate circumstance that longstanding, increasingly out-of-date treaty-based mutual agreement procedures (MAP) and domestic resolution processes are being overwhelmed by both the complexity and sheer volume of international tax disputes they are meant to, but are ill-equipped to, handle. The underlying tensions include:  Disputes over historic residence versus source country treaty and transfer pricing (TP) models;  Revenue collection from international businesses for all countries;  Base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) measures;  Competition between countries for MNE tax bases; Focus on Tax Strategies & Developments | January 2016 7 .