Description

DECEMBER 2015

IRS Updates Administrative

Appeals Process for Cases

Docketed in Tax Court

By Jean A. Pawlow and Joshua Ellenberg

In Notice 2015-72, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS)

provided a proposed revenue procedure to update Rev. Proc.

87-24, 1987-1 C.B. 720, which describes the procedures for

handling docketed cases in furtherance of the IRS Office of

Appeals’ mission to resolve tax controversies without litigation

in a manner that is fair and impartial to both the government

and the taxpayer.

If finalized, this proposed revenue procedure would supersede Rev. Proc. 87-24. The IRS noted that since the 1987 issuance of Rev.

Proc. 8724, the IRS has been reorganized several times, the volume of litigation in the Tax Court has increased, and the IRS has adopted new policies and procedures to more efficiently manage its workload. Therefore, the notice states, the old revenue procedure should be updated to more accurately reflect the procedures utilized in managing the flow of docketed cases between the Office of Appeals (Appeals) and the Office of Chief Counsel (Counsel), and also to ensure that docketed cases are handled consistently throughout the For example, the updated Rev.

Proc. stresses that, except in rare circumstances, Counsel will refer docketed cases to Appeals for settlement consideration. Under the old Rev. Proc., it was not entirely clear that Counsel was required to refer docketed cases back to Appeals.

Although in practice Counsel often did refer docketed cases to Appeals, the language of the new Rev. Proc. should give more leverage to taxpayers arguing for a referral back to Appeals. Rev.

Proc. 87-24 also explicitly states that for cases involving deficiencies over $10,000, Appeals must promptly return the case to Counsel when no progress is being made towards settling the case. The proposed update omits this statement, perhaps indicating a willingness to give Appeals more leeway in deciding when to send a case back to Counsel. Further, the proposed Rev.

Proc. addresses the frequent occurrence of cases in which Appeals is forced to issue a notice of deficiency or make a determination without having fully considered the issues because of an impending expiration of the statute of limitations on assessment. The notice states that if Appeals requests that the case be returned to it for full consideration once docketed, it will be treated as if Appeals did not issue the notice of deficiency or make the determination. United States. An additional, somewhat puzzling, revision in the updated Rev. Proc.

is sure to be a source of many comments. The notice Although the notice asserts that the proposed update “is not intended to materially modify the current practice of referring explains that those “rare circumstances” in which Counsel will not refer docketed cases for settlement include instances where an “issue has been designated for litigation by Counsel” docketed cases to Appeals for settlement currently utilized in the vast majority of cases,” it does in fact contain some significant changes from Rev. Proc.

87-24. and where “Division Counsel or a higher level Counsel official determines that referral is not in the interest of sound tax administration.” This provision seems to contradict Rev. Proc. 87-24, which only allowed Counsel to make such a decision in Boston Brussels Chicago Dallas Düsseldorf Frankfurt Houston London Los Angeles Miami Milan Munich New York Orange County Paris Rome Seoul Silicon Valley Washington, D.C. Strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices (Shanghai) . FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY consultation with Appeals. The IRS will go through a long AD Investment process, with input from Appeals and opportunities for the taxpayer to argue against designation, before it designates an In AD Investment, the Tax Court left many tax practitioners issue for litigation, but ultimately IRS chief counsel has final say on whether to designate the case for litigation. If the proposed Rev. Proc.

in fact intends to take Appeals—an surprised and dismayed when it held that taxpayers asserting good-faith defenses to accuracy-related penalties had waived the attorney-client privilege by putting their independent organization—out of this process and give sole discretion to the IRS in deciding when to refer cases to Appeals, taxpayers should be concerned. state of mind at issue. The case involved two partnerships engaging in what the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) described as Son-of-Boss tax shelter transactions designed Another change in the proposed Rev. Proc., however, should be quite welcome to taxpayers.

In an effort to preserve Appeals’ independence, the notice clarifies that even in docketed cases Appeals may exclude Counsel from settlement conferences with the taxpayer if, after considering the views of both Counsel and the taxpayer, Appeals determines Counsel’s participation in the settlement conference will not further settlement of the case. The proposed Rev. Proc.

also addresses the coordination between Appeals and Counsel when a taxpayer raises an issue for the first time while the docketed case is with Appeals for settlement consideration. Lastly, the proposed Rev. Proc. removes the prior exclusion for cases governed by rulings by the National Office in employee plans and exempt organizations to reflect recent organization changes in the Tax Exempt and Government Entities Division. Tax Court Order Reaffirms that State of Mind Defense Waives AttorneyClient Privilege By Jean A.

Pawlow and Joshua Ellenberg In Eaton Corp. v. Commissioner, No.

5576-12 (2015), Special Trial Judge Daniel A. Guy, Jr. reinforced the U.S. Tax Court’s controversial opinion from AD Investment 2000 Fund LLC v.

Commissioner, 142 T.C. 248 (2014), which held that a taxpayer implicitly waives its attorneyclient privilege simply by asserting a reasonable belief to create artificial tax losses. Based on these transactions, the IRS adjusted partnership items and determined that various section 6662 accuracy-related penalties should apply to any resulting underpayments of tax. The partnerships defended against the penalties by claiming two commonly pled affirmative defenses under section 6664: the reasonable belief defense and the reasonable cause/good faith defense.

Although the taxpayers had received six opinion letters regarding the transaction from the law firm Brown & Wood LLP, they did not claim that their “reasonable belief” and “good faith” centered on that professional advice. Instead, they stated that they had relied on their own self-determination, and thus they claimed that those tax opinions were not relevant to their defenses and should therefore be protected by the attorney-client privilege. In an opinion by Judge James S. Halpern that stunned the tax bar, the Tax Court held that the taxpayers had implicitly waived the attorney-client privilege by raising the reasonable belief defense.

Judge Halpern wrote that the taxpayers’ defense “placed the partnerships’ legal knowledge, understanding, and beliefs into contention, and those are topics upon which the opinions may bear.” He further opined that if the partnerships had relied on the legal knowledge of their lawyers in forming their reasonable and good faith belief that the tax treatment of the items in question was more likely than not the proper treatment, then “it is only fair that respondent be allowed to inquire into the bases of that person’s knowledge, understanding, and beliefs including the opinions (if considered).” Thus, Judge Halpern ordered production of the once privileged documents. defense to accuracy-related penalties. Eaton Corp. Many tax lawyers were cautiously optimistic that the Tax Court’s ruling would be limited to the area of tax shelters, 2 Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 . FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY where courts may be less inclined to allow the attorney- Investment. In the meantime, taxpayers should weigh their client privilege. These hopes were dashed by the order in Eaton Corp., which revolved around the IRS’s motion to options and closely evaluate alternatives before invoking a 6664 state of mind defense to an accuracy-related penalty. compel the production of certain documents held by the taxpayer. These documents comprised internal e-mails, memos and data compilations exchanged between the taxpayer and the taxpayer’s legal counsel at Mayer Brown LLP, and tax practitioners at PricewaterhouseCoopers and KPMG.

The documents were generated in support of the U.S. Tax Court Upholds Favorable Definition of Insurance By Elizabeth Erickson, Kristen E. Hazel and Justin Jesse taxpayer’s negotiation of an advanced pricing agreement (APA) with the IRS. On September 21, 2015, the U.S.

Tax Court released its decision in R.V.I. Guaranty Co. v.

Commissioner (RVI), 145 T.C. No. 9, and ruled that the taxpayer’s residual value Special Trial Judge Daniel A.

Guy, Jr. first rejected the insurance contracts constituted insurance for U.S. federal income tax purposes.

As a result, the taxpayer was able to more closely match premium inclusions with loss deductions. IRS’s argument that these documents weren’t at all privileged. Finding that the documents under review were prepared because of the prospect of litigation and that the communications in question were intended to be confidential, the court concluded that the documents were theoretically protected from discovery based on the attorney-client and tax practitioner privileges, as well as under the work product doctrine. Next, the judge turned to the question of whether the taxpayer had implicitly waived those privileges by asserting the reasonable cause/good faith defense. The taxpayer tried to differentiate its facts from those of AD Investment by arguing that the AD Investment court had only properly analyzed the reasonable belief defense and not the reasonable cause/good faith defense that was being utilized in the taxpayer’s case. Here, however, the judge agreed with the IRS that AD Investment was controlling, concluding that the taxpayer’s “reasonable cause/good faith defense puts into contention the subjective intent and state of mind of those who acted for [the taxpayer] and [taxpayer]’s good-faith efforts to comply with the tax law.” Thus, the judge stated, “it would be unfair to deprive [the IRS] of knowledge of the legal and tax advice that [taxpayer] received in the course of requesting and negotiating the APA.” Accordingly, the court held that by raising the reasonable cause/good faith defense, the taxpayer had waived its right to proclaim the documents privileged. Conclusion It is disheartening that the protections offered by the attorney client privilege are eroding.

It remains to be seen whether and to what extent the full Tax Court will continue to apply AD This case represents a third victory for taxpayers with respect to the definition of insurance for tax purposes, following RentA-Center v. Commmissioner, 142 T.C. 1 (2014), and Securitas Holdings, Inc.

v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo.

2014-225. Background R.V.I. Guaranty Co. Ltd.

(RVIG), is a Bermuda corporation registered and regulated as an insurance company under the Bermuda Insurance Act of 1978. As an electing domestic taxpayer under Internal Revenue Code (Code) § 953(d), RVIG is the common parent of an affiliated group of corporations that includes R.V.I. American Insurance Company (RVIA), a property and casualty insurance company domiciled in Connecticut.

RVIG and RVIA are together referred to as the “taxpayer.” During the years at issue, the taxpayer sold residual value insurance. Residual value insurance policies are generally offered to leasing companies, manufacturers and financial institutions, and cover assets such as passenger vehicles, commercial real estate and commercial equipment. The policies operate to protect the insured against the risk that the value of the insured asset at the end of the lease term will be lower than the expected value. For example, an insured may be a vehicle leasing company.

In setting the periodic lease payments, the insured must estimate the residual value of the vehicles on termination of the lease. A residual value insurer covers against the risk that the actual value of the vehicles upon termination of the lease will be lower than the expected value. Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 3 . FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY During RVIG’s 2006 audit, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) The IRS countered with three experts who concluded that the concluded that the policies were not “insurance” for U.S. federal income tax purposes, based largely on the IRS’s policies covered a speculative risk, much like a stock investment. While the IRS’s experts acknowledged that the determination that the policyholders were purchasing protection against investment or business risk rather than insurance risk. The IRS assessed a deficiency of more than risks were distributed, they also concluded that the risks were highly correlated, thus challenging the notion that the aggregate risk was truly distributed. $55 million, and the taxpayer timely petitioned the Tax Court for redetermination of this deficiency. U.S. Federal Tax Definition of Insurance The fundamental issue addressed by the Tax Court was whether the residual value insurance contracts protected the insured against an investment risk or an insurance risk. Neither the Code nor the Treasury Regulations define the term “insurance,” but over the years a body of law has developed, and the following guiding principles have emerged:  Insurance involves both risk shifting and risk distribution. The risk of loss must shift from the insured to the insurer, and the insurer must pool multiple risks of multiple insureds in order to diversify its exposure; this is known as the “law of large numbers.” After admitting to a methodological error, the IRS’s experts seemingly conceded that the taxpayer had a significant risk of loss.

Nevertheless, the experts concluded that the policies were not typical insurance policies, i.e., not insurance in the commonly accepted sense, because they did not insure against a fortuitous event and the insurer did not face any timing risk. The Tax Court dispensed with the IRS’s contentions regarding risk shifting and risk distribution by concluding that the taxpayer’s actual loss experience demonstrated that it bore a significant risk of loss (thus, risk had been shifted) and that there was meaningful risk distribution. There were more than two million separate risk units of varying types (passenger vehicles, real estate properties and commercial equipment), and the risk units were distributed over varying lease terms.  The transaction must constitute insurance in its commonly accepted sense. While the court acknowledged that the risks could be correlated to, for example, a recession, the court noted that the diversification achieved within the asset pool and lease  Especially relevant to the R.V.I. decision, the risk transferred must be an “insurance risk.” terms mitigated any systemic risk.

Moreover, the court observed that many insurers face systemically correlated risks. The taxpayer’s business model was not materially different Against that framework, and notwithstanding the fact that than the business model of those insurers. commercial insurance companies have offered residual value insurance for more than 80 years, the IRS concluded that the contracts protected the insureds against investment risk and Investment or Insurance Risk thus were not insurance for tax purposes. The court then rejected the IRS’s contention that the policies covered an uninsurable “investment risk.” The court Trial considered first whether the contracts were insurance in the commonly understood sense of the word. At trial, the taxpayer’s experts concluded that the policies covered an insurance risk, much like mortgage guaranty It framed its analysis by considering five factors: insurance. The taxpayer’s experts also concluded that the risks were distributed in the same way as any other property and casualty carrier, that the taxpayer was subject to  Whether the insurer was organized and operated as an insurance company by the states in which it conducted underwriting risk and that the risk was transferred. business (taxpayer was)  Whether the insurer was adequately capitalized (taxpayer was) 4 Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 . FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY  Whether the insurance policies were valid and binding (taxpayer’s contracts were) nature of the risk itself. The court declined to accept the narrow definition of risk offered by the IRS and instead looked to the more practical guidance offered by the taxpayer.  Whether the premiums were reasonable in relation to the risk of loss (premiums were negotiated at arm’s length between taxpayer and its insureds)  Whether premiums were duly paid and loss claims were duly satisfied (when losses occurred, insureds filed claims and taxpayer paid those claims) The insured simply has to shift to the insurer the risk from a “hazard,” a “specific contingency,” or some “direct or indirect economic loss.” The residual value insurance contracts offered by the taxpayer did just that. The insured shifted to the taxpayer the risk that the covered property would decline in value. The types of events that resulted in a loss under the policies closely Even though the taxpayer readily met the five requirements, resembled the losses under, for example, mortgage guaranty insurance—a product long accepted as insurance. the IRS concluded that the policies did not qualify as insurance because they differed from policies with which most people are familiar.

The IRS noted that the policies did not pay on the Having concluded that the policies had the hallmark features occurrence of a “fortuitous event,” such as a car crash. Rather, the policies paid, if at all, at the end of the lease term, which was not random or fortuitous. The court, however, held that of insurance (risk shifting, risk distribution, commonly accepted notions of insurance, and insurance risk) the court determined that the policies were insurance for U.S.

federal income tax purposes. losses under the policies were caused by fortuitous events outside the control of the taxpayer. The fact that a loss must persist to the end of the term of the lease does not make the Waiting for Relief from Retroactivity events that cause the loss (e.g., recession, interest rate spikes, bank failures) any less fortuitous, the court stated. Thus, the Tax Court concluded that the contracts were Retroactivity is an endemic problem in the state tax world. The insurance in the commonly accepted sense. The court next considered whether the contracts covered insurance risk.

The court acknowledged that there was little guidance with respect to the difference between “insurance risk” and “investment risk.” The court determined that the policies involved insurance risk from the taxpayer’s perspective. The taxpayer’s business model depended upon more than investment returns; its model depended on the ability of its underwriters to price the risks to derive a sufficient pool of premiums to cover the aggregate losses. This is the same pricing model used by insurance companies generally. The court also determined that the policies were insurance risk from the perspective of the insureds. The court first looked to state law and noted that New York and Connecticut had defined residual value policies as a form of “insurance” since 1989, and in 1991 the Washington Supreme Court had reached the same conclusion. By Mark Yopp past year has seen retroactive repeal of the Multistate Tax Compact (MTC) in Michigan, as well as significant retroactivity issues in New York, New Jersey and Virginia.

Relief appeared to be on the way until the Supreme Court of the United States denied certiorari in a Washington estate tax case, Hambleton v. Washington, on October 13, 2015. The Supreme Court’s decision came just two weeks after the Michigan Court of Appeals upheld a retroactive period of almost seven years. The Hambleton petition urged the Supreme Court to take the case in order to resolve the uncertainty of “how long is too long” when it comes to retroactive taxes, citing multiple examples of past and ongoing litigation in which lower courts have taken divergent approaches to the length of permissible retroactivity.

For example, the petition cited the ongoing litigation in Michigan over the MTC’s apportionment election. In July 2014, in International Business Machines Corp. v. Michigan Department of Treasury, the Michigan Supreme Court held that IBM could apportion its income using the so- The taxpayer’s regulators and external auditors uniformly called “MTC election,” which allowed a taxpayer to use a three-factor formula consisting of property, payroll and receipts to apportion income, rather than the state’s standard formula. reached the same conclusion. The court then scrutinized the 852 N.W.2d 865 (Mich.

2014). In September 2014, however, Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 5 . FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY the Michigan legislature retroactively repealed the MTC of those trust assets. In 2013, however, the election and effectively overturned the IBM decision. Fifty taxpayers challenged the retroactive repeal, and those cases Washington Legislature amended the estate tax statutes retroactively back to 2005, exposing their were consolidated. estates to nearly two million dollars of back taxes. On September 29, 2015, the Michigan Court of Appeals upheld the retroactive repeal of the MTC election in the In 2005, Washington State enacted an estate tax that was intended to operate on a standalone basis, separate from the consolidated cases. Gillette Commercial Operations N.

Am. & Subsidiaries v. Dep’t of Treasury, et al, Dkt.

No. 325258 (Mich. Ct. Claims, Sep.

29, 2015). While the case included several federal estate tax. In interpreting the new law, the Washington Department of Revenue issued regulations that the transfer of property from the petitioners’ husbands to the petitioners state and federal constitutional and statutory issues, this article will focus on the due process clause. through a Qualified Terminable Interest Property (QTIP) trust was not subject to the Washington estate tax.

The Department subsequently reversed its position and assessed tax. The due process clause (theoretically) prohibits retroactive Petitioners, along with other estates, challenged the Department’s position and won in Washington Supreme Court (In re Estate of Bracken, 290 P.3d 99 (Wash. 2012)). laws, because persons must be able to know what the law is, and retroactive law changes prevent a person from having that knowledge. The Supreme Court of the United States’ primary case regarding when due process prohibits a retroactive law is U.S.

v. Carlton, 512 U.S. 26 (1994).

In Carlton, the Supreme Court established a two-part test to determine whether the In 2013, the Washington legislature amended the estate tax to retroactively adopt the Department’s position, going back to 2005. The petitioners challenged this new law and again retroactive effect of a law is allowed under the due process clause. First, the legislature’s act must be neither arbitrary nor illegitimate.

Second, the legislature must act promptly and only fought to the Washington Supreme Court, which this time held in favor of the Department and concluded that the retroactive change satisfied the due process clause under a rational basis enact a “modest” period of retroactivity. standard. This chain of events is inherently unfair and, if allowed, potentially subjects taxpayers to new tax liabilities at any time. In Gillette, the Michigan Court of Appeals determined that a six-and-a-half-year period of retroactivity was modest. It is not clear why this length of time was deemed modest, but many other Michigan cases uphold laws with retroactive periods of similar length.

Outside of Carlton, which approved a Although disappointing, the Supreme Court of the United States’ denial of certiorari in Hambleton is not surprising. The Supreme Court has declined previous opportunities to review retroactive period of one year, the Supreme Court has given little guidance on the definition of “modest.” retroactive state tax impositions (see, e.g., Miller v. Johnson Controls, Inc., 296 S.W.3d 392 (Ky.

2009), cert. denied, 560 U.S. 935 (2010)).

The Gillette case will continue up the chain Taxpayers were sorely disappointed when Hambleton was in Michigan and likely will be appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, regardless of who prevails in the denied certiorari, because it is hard to imagine a more sympathetic situation for a due process retroactivity challenge to a state tax. The Hambleton case involved two widows’ estates. As stated in the petition: Michigan Supreme Court.

As explained in the Hambleton certiorari petition and the supporting amicus briefs, the Supreme Court needs to revisit the retroactivity issue and act Helen Hambleton died in 2006, and Jessie Macbride as a check as states continue to aggressively seek ways to raise additional revenue. died in 2007. Each was the passive lifetime beneficiary of a trust established in her deceased husband’s estate, and neither possessed a power under the trust instrument to dispose of the trust assets. Under the Washington estate tax law at the time of their deaths, the tax did not apply to the value 6 Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 .

FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY McDERMOTT TAX CONTROVERSY HIGHLIGHT EDITOR U.S. News & Best Lawyers Names McDermott “Tax Law Firm of the Year” and Awards Firm Top Rankings in More than 20 National Practices For more information, please contact your regular McDermott lawyer, or: McDermott Will & Emery LLP has been selected as “Tax Law Firm of the Year” in the 2016 “Best Law Firms” survey published by U.S. News Media Group and Best Lawyers. This is the second time in four years that the Firm has received this prestigious recognition. Additionally, McDermott received 31 national rankings and 98 regional rankings this year. Jean A.

Pawlow Co-Chair, Tax Controversy Practice +1 202 756 8297 (DC) +1 650 815 7558 (CA) jpawlow@mwe.com For more information about McDermott Will & Emery visit www.mwe.com The material in this publication may not be reproduced, in whole or part without acknowledgement of its source and copyright. Focus on Tax Controversy is intended to provide information of general interest in a summary manner and should not be construed as individual legal advice. Readers should consult with their McDermott Will & Emery lawyer or other professional counsel before acting on the information contained in this publication. ©2015 McDermott Will & Emery.

The following legal entities are collectively referred to as “McDermott Will & Emery,” “McDermott” or “the Firm”: McDermott Will & Emery LLP, McDermott Will & Emery AARPI, McDermott Will & Emery Belgium LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Rechtsanwälte Steuerberater LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Studio Legale Associato and McDermott Will & Emery UK LLP. These entities coordinate their activities through service agreements. McDermott has a strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices, a separate law firm. This communication may be considered attorney advertising.

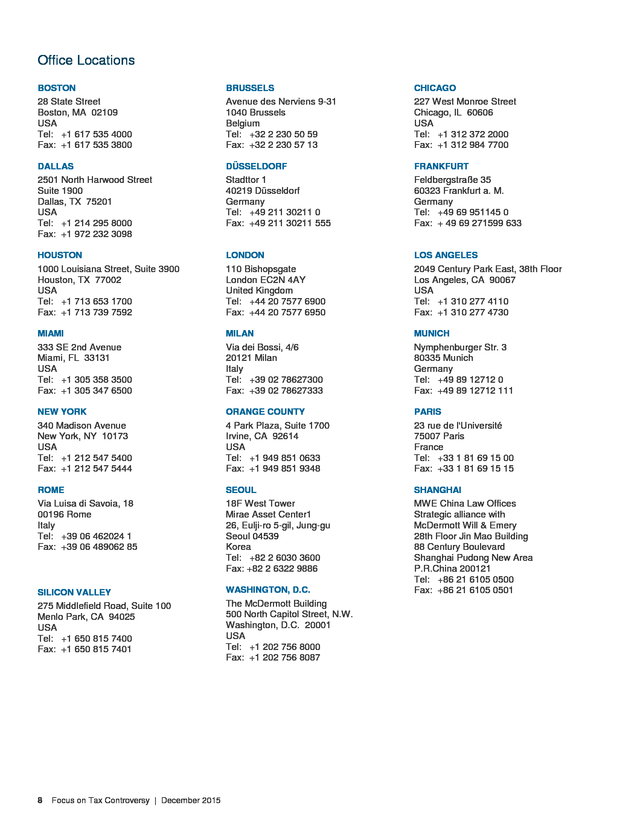

Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 7 . Office Locations BOSTON BRUSSELS CHICAGO 28 State Street Boston, MA 02109 USA Tel: +1 617 535 4000 Fax: +1 617 535 3800 Avenue des Nerviens 9-31 1040 Brussels Belgium Tel: +32 2 230 50 59 Fax: +32 2 230 57 13 227 West Monroe Street Chicago, IL 60606 USA Tel: +1 312 372 2000 Fax: +1 312 984 7700 DALLAS DÜSSELDORF FRANKFURT 2501 North Harwood Street Suite 1900 Dallas, TX 75201 USA Tel: +1 214 295 8000 Fax: +1 972 232 3098 Stadttor 1 40219 Düsseldorf Germany Tel: +49 211 30211 0 Fax: +49 211 30211 555 Feldbergstraße 35 60323 Frankfurt a. M. Germany Tel: +49 69 951145 0 Fax: + 49 69 271599 633 HOUSTON LONDON LOS ANGELES 1000 Louisiana Street, Suite 3900 Houston, TX 77002 USA Tel: +1 713 653 1700 Fax: +1 713 739 7592 110 Bishopsgate London EC2N 4AY United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7577 6900 Fax: +44 20 7577 6950 2049 Century Park East, 38th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90067 USA Tel: +1 310 277 4110 Fax: +1 310 277 4730 MIAMI MILAN MUNICH 333 SE 2nd Avenue Miami, FL 33131 USA Tel: +1 305 358 3500 Fax: +1 305 347 6500 Via dei Bossi, 4/6 20121 Milan Italy Tel: +39 02 78627300 Fax: +39 02 78627333 Nymphenburger Str. 3 80335 Munich Germany Tel: +49 89 12712 0 Fax: +49 89 12712 111 NEW YORK ORANGE COUNTY PARIS 340 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10173 USA Tel: +1 212 547 5400 Fax: +1 212 547 5444 4 Park Plaza, Suite 1700 Irvine, CA 92614 USA Tel: +1 949 851 0633 Fax: +1 949 851 9348 23 rue de l'Université 75007 Paris France Tel: +33 1 81 69 15 00 Fax: +33 1 81 69 15 15 ROME SEOUL SHANGHAI Via Luisa di Savoia, 18 00196 Rome Italy Tel: +39 06 462024 1 Fax: +39 06 489062 85 18F West Tower Mirae Asset Center1 26, Eulji-ro 5-gil, Jung-gu Seoul 04539 Korea Tel: +82 2 6030 3600 Fax: +82 2 6322 9886 SILICON VALLEY WASHINGTON, D.C. MWE China Law Offices Strategic alliance with McDermott Will & Emery 28th Floor Jin Mao Building 88 Century Boulevard Shanghai Pudong New Area P.R.China 200121 Tel: +86 21 6105 0500 Fax: +86 21 6105 0501 275 Middlefield Road, Suite 100 Menlo Park, CA 94025 USA Tel: +1 650 815 7400 Fax: +1 650 815 7401 The McDermott Building 500 North Capitol Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 USA Tel: +1 202 756 8000 Fax: +1 202 756 8087 8 Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 .

If finalized, this proposed revenue procedure would supersede Rev. Proc. 87-24. The IRS noted that since the 1987 issuance of Rev.

Proc. 8724, the IRS has been reorganized several times, the volume of litigation in the Tax Court has increased, and the IRS has adopted new policies and procedures to more efficiently manage its workload. Therefore, the notice states, the old revenue procedure should be updated to more accurately reflect the procedures utilized in managing the flow of docketed cases between the Office of Appeals (Appeals) and the Office of Chief Counsel (Counsel), and also to ensure that docketed cases are handled consistently throughout the For example, the updated Rev.

Proc. stresses that, except in rare circumstances, Counsel will refer docketed cases to Appeals for settlement consideration. Under the old Rev. Proc., it was not entirely clear that Counsel was required to refer docketed cases back to Appeals.

Although in practice Counsel often did refer docketed cases to Appeals, the language of the new Rev. Proc. should give more leverage to taxpayers arguing for a referral back to Appeals. Rev.

Proc. 87-24 also explicitly states that for cases involving deficiencies over $10,000, Appeals must promptly return the case to Counsel when no progress is being made towards settling the case. The proposed update omits this statement, perhaps indicating a willingness to give Appeals more leeway in deciding when to send a case back to Counsel. Further, the proposed Rev.

Proc. addresses the frequent occurrence of cases in which Appeals is forced to issue a notice of deficiency or make a determination without having fully considered the issues because of an impending expiration of the statute of limitations on assessment. The notice states that if Appeals requests that the case be returned to it for full consideration once docketed, it will be treated as if Appeals did not issue the notice of deficiency or make the determination. United States. An additional, somewhat puzzling, revision in the updated Rev. Proc.

is sure to be a source of many comments. The notice Although the notice asserts that the proposed update “is not intended to materially modify the current practice of referring explains that those “rare circumstances” in which Counsel will not refer docketed cases for settlement include instances where an “issue has been designated for litigation by Counsel” docketed cases to Appeals for settlement currently utilized in the vast majority of cases,” it does in fact contain some significant changes from Rev. Proc.

87-24. and where “Division Counsel or a higher level Counsel official determines that referral is not in the interest of sound tax administration.” This provision seems to contradict Rev. Proc. 87-24, which only allowed Counsel to make such a decision in Boston Brussels Chicago Dallas Düsseldorf Frankfurt Houston London Los Angeles Miami Milan Munich New York Orange County Paris Rome Seoul Silicon Valley Washington, D.C. Strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices (Shanghai) . FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY consultation with Appeals. The IRS will go through a long AD Investment process, with input from Appeals and opportunities for the taxpayer to argue against designation, before it designates an In AD Investment, the Tax Court left many tax practitioners issue for litigation, but ultimately IRS chief counsel has final say on whether to designate the case for litigation. If the proposed Rev. Proc.

in fact intends to take Appeals—an surprised and dismayed when it held that taxpayers asserting good-faith defenses to accuracy-related penalties had waived the attorney-client privilege by putting their independent organization—out of this process and give sole discretion to the IRS in deciding when to refer cases to Appeals, taxpayers should be concerned. state of mind at issue. The case involved two partnerships engaging in what the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) described as Son-of-Boss tax shelter transactions designed Another change in the proposed Rev. Proc., however, should be quite welcome to taxpayers.

In an effort to preserve Appeals’ independence, the notice clarifies that even in docketed cases Appeals may exclude Counsel from settlement conferences with the taxpayer if, after considering the views of both Counsel and the taxpayer, Appeals determines Counsel’s participation in the settlement conference will not further settlement of the case. The proposed Rev. Proc.

also addresses the coordination between Appeals and Counsel when a taxpayer raises an issue for the first time while the docketed case is with Appeals for settlement consideration. Lastly, the proposed Rev. Proc. removes the prior exclusion for cases governed by rulings by the National Office in employee plans and exempt organizations to reflect recent organization changes in the Tax Exempt and Government Entities Division. Tax Court Order Reaffirms that State of Mind Defense Waives AttorneyClient Privilege By Jean A.

Pawlow and Joshua Ellenberg In Eaton Corp. v. Commissioner, No.

5576-12 (2015), Special Trial Judge Daniel A. Guy, Jr. reinforced the U.S. Tax Court’s controversial opinion from AD Investment 2000 Fund LLC v.

Commissioner, 142 T.C. 248 (2014), which held that a taxpayer implicitly waives its attorneyclient privilege simply by asserting a reasonable belief to create artificial tax losses. Based on these transactions, the IRS adjusted partnership items and determined that various section 6662 accuracy-related penalties should apply to any resulting underpayments of tax. The partnerships defended against the penalties by claiming two commonly pled affirmative defenses under section 6664: the reasonable belief defense and the reasonable cause/good faith defense.

Although the taxpayers had received six opinion letters regarding the transaction from the law firm Brown & Wood LLP, they did not claim that their “reasonable belief” and “good faith” centered on that professional advice. Instead, they stated that they had relied on their own self-determination, and thus they claimed that those tax opinions were not relevant to their defenses and should therefore be protected by the attorney-client privilege. In an opinion by Judge James S. Halpern that stunned the tax bar, the Tax Court held that the taxpayers had implicitly waived the attorney-client privilege by raising the reasonable belief defense.

Judge Halpern wrote that the taxpayers’ defense “placed the partnerships’ legal knowledge, understanding, and beliefs into contention, and those are topics upon which the opinions may bear.” He further opined that if the partnerships had relied on the legal knowledge of their lawyers in forming their reasonable and good faith belief that the tax treatment of the items in question was more likely than not the proper treatment, then “it is only fair that respondent be allowed to inquire into the bases of that person’s knowledge, understanding, and beliefs including the opinions (if considered).” Thus, Judge Halpern ordered production of the once privileged documents. defense to accuracy-related penalties. Eaton Corp. Many tax lawyers were cautiously optimistic that the Tax Court’s ruling would be limited to the area of tax shelters, 2 Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 . FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY where courts may be less inclined to allow the attorney- Investment. In the meantime, taxpayers should weigh their client privilege. These hopes were dashed by the order in Eaton Corp., which revolved around the IRS’s motion to options and closely evaluate alternatives before invoking a 6664 state of mind defense to an accuracy-related penalty. compel the production of certain documents held by the taxpayer. These documents comprised internal e-mails, memos and data compilations exchanged between the taxpayer and the taxpayer’s legal counsel at Mayer Brown LLP, and tax practitioners at PricewaterhouseCoopers and KPMG.

The documents were generated in support of the U.S. Tax Court Upholds Favorable Definition of Insurance By Elizabeth Erickson, Kristen E. Hazel and Justin Jesse taxpayer’s negotiation of an advanced pricing agreement (APA) with the IRS. On September 21, 2015, the U.S.

Tax Court released its decision in R.V.I. Guaranty Co. v.

Commissioner (RVI), 145 T.C. No. 9, and ruled that the taxpayer’s residual value Special Trial Judge Daniel A.

Guy, Jr. first rejected the insurance contracts constituted insurance for U.S. federal income tax purposes.

As a result, the taxpayer was able to more closely match premium inclusions with loss deductions. IRS’s argument that these documents weren’t at all privileged. Finding that the documents under review were prepared because of the prospect of litigation and that the communications in question were intended to be confidential, the court concluded that the documents were theoretically protected from discovery based on the attorney-client and tax practitioner privileges, as well as under the work product doctrine. Next, the judge turned to the question of whether the taxpayer had implicitly waived those privileges by asserting the reasonable cause/good faith defense. The taxpayer tried to differentiate its facts from those of AD Investment by arguing that the AD Investment court had only properly analyzed the reasonable belief defense and not the reasonable cause/good faith defense that was being utilized in the taxpayer’s case. Here, however, the judge agreed with the IRS that AD Investment was controlling, concluding that the taxpayer’s “reasonable cause/good faith defense puts into contention the subjective intent and state of mind of those who acted for [the taxpayer] and [taxpayer]’s good-faith efforts to comply with the tax law.” Thus, the judge stated, “it would be unfair to deprive [the IRS] of knowledge of the legal and tax advice that [taxpayer] received in the course of requesting and negotiating the APA.” Accordingly, the court held that by raising the reasonable cause/good faith defense, the taxpayer had waived its right to proclaim the documents privileged. Conclusion It is disheartening that the protections offered by the attorney client privilege are eroding.

It remains to be seen whether and to what extent the full Tax Court will continue to apply AD This case represents a third victory for taxpayers with respect to the definition of insurance for tax purposes, following RentA-Center v. Commmissioner, 142 T.C. 1 (2014), and Securitas Holdings, Inc.

v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo.

2014-225. Background R.V.I. Guaranty Co. Ltd.

(RVIG), is a Bermuda corporation registered and regulated as an insurance company under the Bermuda Insurance Act of 1978. As an electing domestic taxpayer under Internal Revenue Code (Code) § 953(d), RVIG is the common parent of an affiliated group of corporations that includes R.V.I. American Insurance Company (RVIA), a property and casualty insurance company domiciled in Connecticut.

RVIG and RVIA are together referred to as the “taxpayer.” During the years at issue, the taxpayer sold residual value insurance. Residual value insurance policies are generally offered to leasing companies, manufacturers and financial institutions, and cover assets such as passenger vehicles, commercial real estate and commercial equipment. The policies operate to protect the insured against the risk that the value of the insured asset at the end of the lease term will be lower than the expected value. For example, an insured may be a vehicle leasing company.

In setting the periodic lease payments, the insured must estimate the residual value of the vehicles on termination of the lease. A residual value insurer covers against the risk that the actual value of the vehicles upon termination of the lease will be lower than the expected value. Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 3 . FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY During RVIG’s 2006 audit, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) The IRS countered with three experts who concluded that the concluded that the policies were not “insurance” for U.S. federal income tax purposes, based largely on the IRS’s policies covered a speculative risk, much like a stock investment. While the IRS’s experts acknowledged that the determination that the policyholders were purchasing protection against investment or business risk rather than insurance risk. The IRS assessed a deficiency of more than risks were distributed, they also concluded that the risks were highly correlated, thus challenging the notion that the aggregate risk was truly distributed. $55 million, and the taxpayer timely petitioned the Tax Court for redetermination of this deficiency. U.S. Federal Tax Definition of Insurance The fundamental issue addressed by the Tax Court was whether the residual value insurance contracts protected the insured against an investment risk or an insurance risk. Neither the Code nor the Treasury Regulations define the term “insurance,” but over the years a body of law has developed, and the following guiding principles have emerged:  Insurance involves both risk shifting and risk distribution. The risk of loss must shift from the insured to the insurer, and the insurer must pool multiple risks of multiple insureds in order to diversify its exposure; this is known as the “law of large numbers.” After admitting to a methodological error, the IRS’s experts seemingly conceded that the taxpayer had a significant risk of loss.

Nevertheless, the experts concluded that the policies were not typical insurance policies, i.e., not insurance in the commonly accepted sense, because they did not insure against a fortuitous event and the insurer did not face any timing risk. The Tax Court dispensed with the IRS’s contentions regarding risk shifting and risk distribution by concluding that the taxpayer’s actual loss experience demonstrated that it bore a significant risk of loss (thus, risk had been shifted) and that there was meaningful risk distribution. There were more than two million separate risk units of varying types (passenger vehicles, real estate properties and commercial equipment), and the risk units were distributed over varying lease terms.  The transaction must constitute insurance in its commonly accepted sense. While the court acknowledged that the risks could be correlated to, for example, a recession, the court noted that the diversification achieved within the asset pool and lease  Especially relevant to the R.V.I. decision, the risk transferred must be an “insurance risk.” terms mitigated any systemic risk.

Moreover, the court observed that many insurers face systemically correlated risks. The taxpayer’s business model was not materially different Against that framework, and notwithstanding the fact that than the business model of those insurers. commercial insurance companies have offered residual value insurance for more than 80 years, the IRS concluded that the contracts protected the insureds against investment risk and Investment or Insurance Risk thus were not insurance for tax purposes. The court then rejected the IRS’s contention that the policies covered an uninsurable “investment risk.” The court Trial considered first whether the contracts were insurance in the commonly understood sense of the word. At trial, the taxpayer’s experts concluded that the policies covered an insurance risk, much like mortgage guaranty It framed its analysis by considering five factors: insurance. The taxpayer’s experts also concluded that the risks were distributed in the same way as any other property and casualty carrier, that the taxpayer was subject to  Whether the insurer was organized and operated as an insurance company by the states in which it conducted underwriting risk and that the risk was transferred. business (taxpayer was)  Whether the insurer was adequately capitalized (taxpayer was) 4 Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 . FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY  Whether the insurance policies were valid and binding (taxpayer’s contracts were) nature of the risk itself. The court declined to accept the narrow definition of risk offered by the IRS and instead looked to the more practical guidance offered by the taxpayer.  Whether the premiums were reasonable in relation to the risk of loss (premiums were negotiated at arm’s length between taxpayer and its insureds)  Whether premiums were duly paid and loss claims were duly satisfied (when losses occurred, insureds filed claims and taxpayer paid those claims) The insured simply has to shift to the insurer the risk from a “hazard,” a “specific contingency,” or some “direct or indirect economic loss.” The residual value insurance contracts offered by the taxpayer did just that. The insured shifted to the taxpayer the risk that the covered property would decline in value. The types of events that resulted in a loss under the policies closely Even though the taxpayer readily met the five requirements, resembled the losses under, for example, mortgage guaranty insurance—a product long accepted as insurance. the IRS concluded that the policies did not qualify as insurance because they differed from policies with which most people are familiar.

The IRS noted that the policies did not pay on the Having concluded that the policies had the hallmark features occurrence of a “fortuitous event,” such as a car crash. Rather, the policies paid, if at all, at the end of the lease term, which was not random or fortuitous. The court, however, held that of insurance (risk shifting, risk distribution, commonly accepted notions of insurance, and insurance risk) the court determined that the policies were insurance for U.S.

federal income tax purposes. losses under the policies were caused by fortuitous events outside the control of the taxpayer. The fact that a loss must persist to the end of the term of the lease does not make the Waiting for Relief from Retroactivity events that cause the loss (e.g., recession, interest rate spikes, bank failures) any less fortuitous, the court stated. Thus, the Tax Court concluded that the contracts were Retroactivity is an endemic problem in the state tax world. The insurance in the commonly accepted sense. The court next considered whether the contracts covered insurance risk.

The court acknowledged that there was little guidance with respect to the difference between “insurance risk” and “investment risk.” The court determined that the policies involved insurance risk from the taxpayer’s perspective. The taxpayer’s business model depended upon more than investment returns; its model depended on the ability of its underwriters to price the risks to derive a sufficient pool of premiums to cover the aggregate losses. This is the same pricing model used by insurance companies generally. The court also determined that the policies were insurance risk from the perspective of the insureds. The court first looked to state law and noted that New York and Connecticut had defined residual value policies as a form of “insurance” since 1989, and in 1991 the Washington Supreme Court had reached the same conclusion. By Mark Yopp past year has seen retroactive repeal of the Multistate Tax Compact (MTC) in Michigan, as well as significant retroactivity issues in New York, New Jersey and Virginia.

Relief appeared to be on the way until the Supreme Court of the United States denied certiorari in a Washington estate tax case, Hambleton v. Washington, on October 13, 2015. The Supreme Court’s decision came just two weeks after the Michigan Court of Appeals upheld a retroactive period of almost seven years. The Hambleton petition urged the Supreme Court to take the case in order to resolve the uncertainty of “how long is too long” when it comes to retroactive taxes, citing multiple examples of past and ongoing litigation in which lower courts have taken divergent approaches to the length of permissible retroactivity.

For example, the petition cited the ongoing litigation in Michigan over the MTC’s apportionment election. In July 2014, in International Business Machines Corp. v. Michigan Department of Treasury, the Michigan Supreme Court held that IBM could apportion its income using the so- The taxpayer’s regulators and external auditors uniformly called “MTC election,” which allowed a taxpayer to use a three-factor formula consisting of property, payroll and receipts to apportion income, rather than the state’s standard formula. reached the same conclusion. The court then scrutinized the 852 N.W.2d 865 (Mich.

2014). In September 2014, however, Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 5 . FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY the Michigan legislature retroactively repealed the MTC of those trust assets. In 2013, however, the election and effectively overturned the IBM decision. Fifty taxpayers challenged the retroactive repeal, and those cases Washington Legislature amended the estate tax statutes retroactively back to 2005, exposing their were consolidated. estates to nearly two million dollars of back taxes. On September 29, 2015, the Michigan Court of Appeals upheld the retroactive repeal of the MTC election in the In 2005, Washington State enacted an estate tax that was intended to operate on a standalone basis, separate from the consolidated cases. Gillette Commercial Operations N.

Am. & Subsidiaries v. Dep’t of Treasury, et al, Dkt.

No. 325258 (Mich. Ct. Claims, Sep.

29, 2015). While the case included several federal estate tax. In interpreting the new law, the Washington Department of Revenue issued regulations that the transfer of property from the petitioners’ husbands to the petitioners state and federal constitutional and statutory issues, this article will focus on the due process clause. through a Qualified Terminable Interest Property (QTIP) trust was not subject to the Washington estate tax.

The Department subsequently reversed its position and assessed tax. The due process clause (theoretically) prohibits retroactive Petitioners, along with other estates, challenged the Department’s position and won in Washington Supreme Court (In re Estate of Bracken, 290 P.3d 99 (Wash. 2012)). laws, because persons must be able to know what the law is, and retroactive law changes prevent a person from having that knowledge. The Supreme Court of the United States’ primary case regarding when due process prohibits a retroactive law is U.S.

v. Carlton, 512 U.S. 26 (1994).

In Carlton, the Supreme Court established a two-part test to determine whether the In 2013, the Washington legislature amended the estate tax to retroactively adopt the Department’s position, going back to 2005. The petitioners challenged this new law and again retroactive effect of a law is allowed under the due process clause. First, the legislature’s act must be neither arbitrary nor illegitimate.

Second, the legislature must act promptly and only fought to the Washington Supreme Court, which this time held in favor of the Department and concluded that the retroactive change satisfied the due process clause under a rational basis enact a “modest” period of retroactivity. standard. This chain of events is inherently unfair and, if allowed, potentially subjects taxpayers to new tax liabilities at any time. In Gillette, the Michigan Court of Appeals determined that a six-and-a-half-year period of retroactivity was modest. It is not clear why this length of time was deemed modest, but many other Michigan cases uphold laws with retroactive periods of similar length.

Outside of Carlton, which approved a Although disappointing, the Supreme Court of the United States’ denial of certiorari in Hambleton is not surprising. The Supreme Court has declined previous opportunities to review retroactive period of one year, the Supreme Court has given little guidance on the definition of “modest.” retroactive state tax impositions (see, e.g., Miller v. Johnson Controls, Inc., 296 S.W.3d 392 (Ky.

2009), cert. denied, 560 U.S. 935 (2010)).

The Gillette case will continue up the chain Taxpayers were sorely disappointed when Hambleton was in Michigan and likely will be appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, regardless of who prevails in the denied certiorari, because it is hard to imagine a more sympathetic situation for a due process retroactivity challenge to a state tax. The Hambleton case involved two widows’ estates. As stated in the petition: Michigan Supreme Court.

As explained in the Hambleton certiorari petition and the supporting amicus briefs, the Supreme Court needs to revisit the retroactivity issue and act Helen Hambleton died in 2006, and Jessie Macbride as a check as states continue to aggressively seek ways to raise additional revenue. died in 2007. Each was the passive lifetime beneficiary of a trust established in her deceased husband’s estate, and neither possessed a power under the trust instrument to dispose of the trust assets. Under the Washington estate tax law at the time of their deaths, the tax did not apply to the value 6 Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 .

FOCUS ON TAX CONTROVERSY McDERMOTT TAX CONTROVERSY HIGHLIGHT EDITOR U.S. News & Best Lawyers Names McDermott “Tax Law Firm of the Year” and Awards Firm Top Rankings in More than 20 National Practices For more information, please contact your regular McDermott lawyer, or: McDermott Will & Emery LLP has been selected as “Tax Law Firm of the Year” in the 2016 “Best Law Firms” survey published by U.S. News Media Group and Best Lawyers. This is the second time in four years that the Firm has received this prestigious recognition. Additionally, McDermott received 31 national rankings and 98 regional rankings this year. Jean A.

Pawlow Co-Chair, Tax Controversy Practice +1 202 756 8297 (DC) +1 650 815 7558 (CA) jpawlow@mwe.com For more information about McDermott Will & Emery visit www.mwe.com The material in this publication may not be reproduced, in whole or part without acknowledgement of its source and copyright. Focus on Tax Controversy is intended to provide information of general interest in a summary manner and should not be construed as individual legal advice. Readers should consult with their McDermott Will & Emery lawyer or other professional counsel before acting on the information contained in this publication. ©2015 McDermott Will & Emery.

The following legal entities are collectively referred to as “McDermott Will & Emery,” “McDermott” or “the Firm”: McDermott Will & Emery LLP, McDermott Will & Emery AARPI, McDermott Will & Emery Belgium LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Rechtsanwälte Steuerberater LLP, McDermott Will & Emery Studio Legale Associato and McDermott Will & Emery UK LLP. These entities coordinate their activities through service agreements. McDermott has a strategic alliance with MWE China Law Offices, a separate law firm. This communication may be considered attorney advertising.

Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 7 . Office Locations BOSTON BRUSSELS CHICAGO 28 State Street Boston, MA 02109 USA Tel: +1 617 535 4000 Fax: +1 617 535 3800 Avenue des Nerviens 9-31 1040 Brussels Belgium Tel: +32 2 230 50 59 Fax: +32 2 230 57 13 227 West Monroe Street Chicago, IL 60606 USA Tel: +1 312 372 2000 Fax: +1 312 984 7700 DALLAS DÜSSELDORF FRANKFURT 2501 North Harwood Street Suite 1900 Dallas, TX 75201 USA Tel: +1 214 295 8000 Fax: +1 972 232 3098 Stadttor 1 40219 Düsseldorf Germany Tel: +49 211 30211 0 Fax: +49 211 30211 555 Feldbergstraße 35 60323 Frankfurt a. M. Germany Tel: +49 69 951145 0 Fax: + 49 69 271599 633 HOUSTON LONDON LOS ANGELES 1000 Louisiana Street, Suite 3900 Houston, TX 77002 USA Tel: +1 713 653 1700 Fax: +1 713 739 7592 110 Bishopsgate London EC2N 4AY United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7577 6900 Fax: +44 20 7577 6950 2049 Century Park East, 38th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90067 USA Tel: +1 310 277 4110 Fax: +1 310 277 4730 MIAMI MILAN MUNICH 333 SE 2nd Avenue Miami, FL 33131 USA Tel: +1 305 358 3500 Fax: +1 305 347 6500 Via dei Bossi, 4/6 20121 Milan Italy Tel: +39 02 78627300 Fax: +39 02 78627333 Nymphenburger Str. 3 80335 Munich Germany Tel: +49 89 12712 0 Fax: +49 89 12712 111 NEW YORK ORANGE COUNTY PARIS 340 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10173 USA Tel: +1 212 547 5400 Fax: +1 212 547 5444 4 Park Plaza, Suite 1700 Irvine, CA 92614 USA Tel: +1 949 851 0633 Fax: +1 949 851 9348 23 rue de l'Université 75007 Paris France Tel: +33 1 81 69 15 00 Fax: +33 1 81 69 15 15 ROME SEOUL SHANGHAI Via Luisa di Savoia, 18 00196 Rome Italy Tel: +39 06 462024 1 Fax: +39 06 489062 85 18F West Tower Mirae Asset Center1 26, Eulji-ro 5-gil, Jung-gu Seoul 04539 Korea Tel: +82 2 6030 3600 Fax: +82 2 6322 9886 SILICON VALLEY WASHINGTON, D.C. MWE China Law Offices Strategic alliance with McDermott Will & Emery 28th Floor Jin Mao Building 88 Century Boulevard Shanghai Pudong New Area P.R.China 200121 Tel: +86 21 6105 0500 Fax: +86 21 6105 0501 275 Middlefield Road, Suite 100 Menlo Park, CA 94025 USA Tel: +1 650 815 7400 Fax: +1 650 815 7401 The McDermott Building 500 North Capitol Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 USA Tel: +1 202 756 8000 Fax: +1 202 756 8087 8 Focus on Tax Controversy | December 2015 .