Germany, The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Data Protection 2016, 3rd Edition – April 2016

Hunton & Williams

Description

ICLG

The International Comparative Legal Guide to:

Data Protection 2016

3rd Edition

A practical cross-border insight into data protection law

Published by Global Legal Group, with contributions from:

Affärsadvokaterna i Sverige AB

Bagus Enrico & Partners

Cuatrecasas, Gonçalves Pereira

Deloitte Albania Sh.p.k.

Dittmar & Indrenius

ECIJA ABOGADOS

Eversheds SA

Gilbert + Tobin

GRATA International Law Firm

Hamdan AlShamsi Lawyers & Legal Consultants

Herbst Kinsky Rechtsanwälte GmbH

Hogan Lovells BSTL, S.C.

Hunton & Williams

Lee and Li, Attorneys-at-Law

Matheson

Mori Hamada & Matsumoto

Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP

Pachiu & Associates

Pestalozzi

Rossi Asociados

Subramaniam & Associates (SNA)

Wigley & Company

Wikborg, Rein & Co. Advokatfirma DA

. The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Data Protection 2016

General Chapter:

1

Contributing Editor

Bridget Treacy,

Hunton & Williams

Sales Director

Florjan Osmani

Account Directors

Oliver Smith, Rory Smith

Sales Support Manager

Toni Hayward

Sub Editor

Hannah Yip

Preparing for Change: Europe’s Data Protection Reforms Now a Reality –

Bridget Treacy, Hunton & Williams

1

Country Question and Answer Chapters:

2

Albania

Deloitte Albania Sh.p.k.: Sabina Lalaj & Ened Topi

3

Australia

Gilbert + Tobin: Peter Leonard & Althea Carbon

4

Austria

Herbst Kinsky Rechtsanwälte GmbH: Dr. Sonja Hebenstreit &

Dr. Isabel Funk-Leisch

30

5

Belgium

Hunton & Williams: Wim Nauwelaerts & David Dumont

41

6

Canada

Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP: Adam Kardash & Bridget McIlveen

50

7

15

7

Chile

Rossi Asociados: Claudia Rossi

60

Senior Editor

Rachel Williams

8

China

Hunton & Williams: Manuel E. Maisog & Judy Li

67

Chief Operating Officer

Dror Levy

9

Finland

Dittmar & Indrenius: Jukka Lång & Iiris Keino

74

Group Consulting Editor

Alan Falach

10 France

Hunton & Williams: Claire François

83

11 Germany

Hunton & Williams: Anna Pateraki

92

12 India

Subramaniam & Associates (SNA): Hari Subramaniam &

Aditi Subramaniam

104

13 Indonesia

Bagus Enrico & Partners: Enrico Iskandar & Bimo Harimahesa

116

14 Ireland

Matheson: Anne-Marie Bohan & Andreas Carney

123

15 Japan

Mori Hamada & Matsumoto: Akira Marumo & Hiromi Hayashi

135

16 Kazakhstan

GRATA International Law Firm: Leila Makhmetova & Saule Akhmetova

146

17 Mexico

Hogan Lovells BSTL, S.C.: Mario Jorge Yáñez V.

& Federico de Noriega Olea 155 18 New Zealand Wigley & Company: Michael Wigley 19 Norway Wikborg, Rein & Co. Advokatfirma DA: Dr. Rolf Riisnæs & Dr.

Emily M. Weitzenboeck 171 20 Portugal Cuatrecasas, Gonçalves Pereira: Leonor Chastre 182 21 Romania Pachiu & Associates: Mihaela Cracea & Ioana Iovanesc 193 22 Russia GRATA International Law Firm: Yana Dianova, LL.M. 204 23 South Africa Eversheds SA: Tanya Waksman 217 24 Spain ECIJA ABOGADOS: Carlos Pérez Sanz & Lorena Gallego-Nicasio Peláez 225 25 Sweden Affärsadvokaterna i Sverige AB: Mattias Lindberg 235 26 Switzerland Pestalozzi: Clara-Ann Gordon & Phillip Schmidt 244 27 Taiwan Lee and Li, Attorneys-at-Law: Ken-Ying Tseng & Rebecca Hsiao 254 28 United Arab Emirates Hamdan AlShamsi Lawyers & Legal Consultants: Dr. Ghandy Abuhawash 263 29 United Kingdom Hunton & Williams: Bridget Treacy & Stephanie Iyayi 271 30 USA Hunton & Williams: Aaron P.

Simpson & Chris D. Hydak 280 Group Publisher Richard Firth Published by Global Legal Group Ltd. 59 Tanner Street London SE1 3PL, UK Tel: +44 20 7367 0720 Fax: +44 20 7407 5255 Email: info@glgroup.co.uk URL: www.glgroup.co.uk GLG Cover Design F&F Studio Design GLG Cover Image Source iStockphoto Printed by Ashford Colour Press Ltd. April 2016 Copyright © 2016 Global Legal Group Ltd. All rights reserved No photocopying ISBN 978-1-910083-93-2 ISSN 2054-3786 Strategic Partners 164 Further copies of this book and others in the series can be ordered from the publisher. Please call +44 20 7367 0720 Disclaimer This publication is for general information purposes only.

It does not purport to provide comprehensive full legal or other advice. Global Legal Group Ltd. and the contributors accept no responsibility for losses that may arise from reliance upon information contained in this publication. This publication is intended to give an indication of legal issues upon which you may need advice. Full legal advice should be taken from a qualified professional when dealing with specific situations. WWW.ICLG.CO.UK .

Chapter 11 Germany Hunton & Williams Anna Pateraki 2 Definitions 1 Relevant Legislation and Competent Authorities 2.1 1.1 The principal data protection legislation is the Federal Data Protection Act (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz) (the “FDPA”), which was last amended in 2009 and implements into German law the requirements of the EU Data Protection Directive (95/46/EC) (the “Data Protection Directive”). Where no other law is referred to, references in the following responses to “sections” are references to sections of the FDPA. 1.2 Please provide the key definitions used in the relevant legislation: â– “Personal Data” “Personal data” means any information concerning the personal or material circumstances of an identified or identifiable natural person. â– “Sensitive Personal Data” More commonly known as “special categories of personal data”, which refers to information on racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, health or sex life. â– “Processing” “Processing” means the recording, alteration, transfer, blocking and erasure of personal data. Specifically, irrespective of the procedures applied: What is the principal data protection legislation? Is there any other general legislation that impacts data protection? The 16 German federal states have state-level data protection laws. These laws only apply to the public sector in the relevant state. 1.3 1. “recording” means the entry, recording or preservation of personal data on a storage medium in order that they can be further processed or used; Is there any sector specific legislation that impacts data protection? 2. “alteration” means the modification of the substance of recorded personal data; The Telecommunications Act (Telekommunikationsgesetz) contains sector specific data protection provisions that apply to telecommunications services providers such as internet access providers. The Telemedia Act (Telemediengesetz) also contains sector specific data protection provisions that apply to telemedia service providers such as website providers. Specific rules for online marketing (email, SMS, MMS) are set out in the Unfair Competition Act (Gesetz gegen den unlauteren Wettbewerb). 3. “transfer” means the disclosure of personal data recorded or obtained by data processing to a third party either a) through transfer of the data to a third party, or b) by the third party inspecting or retrieving data available for inspection or retrieval; 4. “blocking” means the identification of recorded personal data in order to restrict their further processing or use; and 5. “erasure” means the deletion of recorded personal data. What is the relevant data protection regulatory authority(ies)? There are 17 state data protection authorities which oversee and enforce private and public sector data protection compliance of entities established in their state. The federal data protection commissioner (Bundesdatenschutzbeauftragter) oversees and enforces data protection compliance within the federal public sector (e.g., federal ministries) as well as certain parts of the postal services and telecommunications services providers’ activities. 92 WWW.ICLG.CO.UK “Data Controller” 1.4 â– “Data controller” means any person or body which collects, processes or uses personal data on his, her or its own behalf, or which commissions others to do the same. â– “Data Processor” The FDPA uses the term “data processor” without explicitly defining it.

The closest to a formal definition is section 11 (1), sentence 1 which reads: “If other bodies collect, process or use personal data on behalf of the controller, the controller shall be responsible for compliance with the provisions of this Act and other data protection provisions.” â– “Data Subject” “Data subject” means an identified or identifiable natural person. © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 . Hunton & Williams Germany Other key definitions – please specify (e.g., “Pseudonymous Data”, “Direct Personal Data”, “Indirect Personal Data”) purpose if it passes the balancing of interests test, the personal data are publicly available, it is required to safeguard a third party’s lawful interests, it is required to guard against dangers to the state or public, or it is for research purposes which clearly outweigh the data subject’s legitimate interests. â– “Pseudonymous Data” “Pseudonymous data” is not defined. However, “pseudonymising” means replacing the data subject’s name and other identifying features with another identifier in order to make it impossible or extremely difficult to identify the data subject. Personal data can be processed on the basis of section 32 (employment purposes) only if this is necessary for hiring decisions or, after hiring, for carrying out or terminating the employment contract. Employees’ personal data may be processed to detect crimes only if there is a documented reason to believe the data subject has committed a crime while employed and the processing is necessary to investigate the crime following a balancing of interests test. â– Data minimisation Section 3a sets out the principles of data minimisation and data economy. The section states that as little personal data as possible should be collected, processed and used, and data processing systems should be chosen and organised accordingly. Further, personal data should be anonymised or pseudonymised if and when the purpose for which they are processed allows it and provided that the effort involved here is not disproportionate. â– Proportionality The proportionality principle is reflected throughout the FDPA.

It is used both where particular operations vis-à-vis personal data are concerned (e.g., when personal data should be anonymised (section 3a)) as well as in the form of the balancing of interests test to determine whether a particular legal basis applies (e.g., section 28). â– “Direct Personal Data” “Direct personal data” is not defined. â– “Indirect Personal Data” “Indirect personal data” is not defined. â– “Anonymising” “Anonymising” means the alteration of personal data so that information concerning personal or material circumstances cannot be attributed to an identified or identifiable natural person, or so that such an attempt at attribution would require a disproportionate amount of time, expense and effort. 3 Key Principles 3.1 What are the key principles that apply to the processing of personal data? â– Transparency There are two transparency requirements enshrined in the FDPA. The first is set out in section 4 (2). This section states that personal data must be collected directly from the data subject and they may only be collected without the data subject’s involvement if it is legally required or if, broadly, the processing purpose necessitates an indirect collection and this indirect collection passes the balancing of interests test. â– Retention The second transparency requirement is that the data subject be informed about the collection and processing of personal data relating to him or her. Section 35 (2) No.

3 states that personal data that are processed for the data controller’s own purposes must be deleted when they are no longer required for the purpose for which they are stored. If personal data are stored for commercial transfer purposes, their continued storage must be evaluated every three or four years to determine whether they are still needed. â– Other key principles – please specify Germany â– There are no other key principles in particular. Where personal data are collected from the data subject, section 4 (3) requires that, if the data subject is not already aware of it, the data controller inform him/her/it as to: (i) the identity of the controller; (ii) the purposes of collection, processing or use; and (iii) the categories of recipients, if the data subject has no expectation that his/her/its data will be transferred to such recipients in the particular case. Where personal data are stored without the data subject’s knowledge, section 33 (1) requires that the data subject be informed of the type of data, the purpose of the collection, processing or use, the identity of the data controller and the categories of recipients, if the data subject has no expectation that his/her/its data will be transferred to such recipients in the particular case. 4 Individual Rights 4.1 What are the key rights that individuals have in relation to the processing of their personal data? â– Access to data The data subject’s right of access is mainly set out in section 34 and concerns access to information about: (1) recorded data relating to them, including information relating to the source of the data; (2) the recipients or categories of recipients to which the data are transferred; and (3) the purpose of recording the data. Data subjects have to be specific about the type of personal data about which information is to be given. Where the personal data are stored for commercial transfer purposes, the data subject must be provided with information about the personal data’s source and recipients, even where such details are not recorded.

The latter information can be withheld, though, if the interest in safeguarding trade secrets outweighs the data subject’s interest in being provided with the information. â– Lawful basis for processing Section 4 (1) states that the collection, processing and use of personal data is only lawful if the FDPA or another law permits or requires it, or if the data subject has consented. The main legal bases set out in the FDPA are: section 28 (data collection and storage for own commercial purposes); section 32 (data collection, processing and use for employment purposes); section 4 (1) and 4a (consent); and section 29 (commercial data collection and storage for transfer purposes). â– Purpose limitation Where personal data is processed on the basis of section 28 (data collection and storage for own commercial purposes), the purpose of the data processing and use must be determined at the time of collection. Section 28 (2) permits a change of More detailed provisions apply where scoring (e.g., credit scores calculated by credit reference agencies) and commercial data transfers are concerned. Information should be provided in writing and free of charge, unless any of the exemptions set out in section 34 apply. ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London WWW.ICLG.CO.UK 93 . Hunton & Williams Correction and deletion The data subject’s rights of correction, deletion and blocking are codified in section 35. Personal data must be corrected if they are inaccurate. They can be deleted at any time unless certain exemptions apply and they must be deleted if: (a) their storage would be unlawful; (b) they concern racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, health or sex life, or criminal or administrative offences the accuracy of which the data controller cannot prove; (c) they are processed for own purposes and they are no longer required for the purpose for which they are stored; or (d) they are processed for commercial transfer purposes and their retention is no longer required. Germany â– In certain circumstances, personal data must be blocked instead of deleted. â– Objection to processing The data subject’s general right to object to the processing of his/her/its personal data is set out in section 35 (5). This section states that personal data must not be collected, processed or used if the data subject has objected and if an evaluation of the data subject’s specific personal circumstances shows that his/her/its legitimate interests outweigh the data controller’s legitimate interests in collecting, processing or using his/her/ its personal data. Section 28 (4) of the FDPA states that if the data subject has objected to the processing of his/her/its personal data for marketing purposes or for the purposes of market or opinion research, then the personal data must not be processed or used for these purposes. Nonetheless, a notification is always required if personal data are processed: (a) for commercial transfer purposes (e.g., for addressselling businesses); (b) for anonymised commercial transfer purposes; or (c) for market and opinion research purposes. 5.2 Section 7 (1) of the Unfair Competition Act states that sending advertisements to a recipient who clearly does not wish to receive advertisements is unlawful. In an online context, section 15 (3) of the Telemedia Act states that telemedia service providers may only use pseudonymised usage profiles for marketing purposes if the user has not objected.

The user must be specifically informed about his/her right to object. â– 5.3 The FDPA does not formalise a complaints procedure. However, it is common for data subjects to contact the relevant data protection authority and for the data protection authority to then investigate the complaint. â– Other key rights – please specify There are no other key rights in particular. Who must register with/notify the relevant data protection authority(ies)? (E.g., local legal entities, foreign legal entities subject to the relevant data protection legislation, representative or branch offices of foreign legal entities subject to the relevant data protection legislation.) All entities to whom German data protection law applies and who cannot avail themselves of either of the exceptions to the general duty to notify must file notifications with the relevant data protection authority. This may include foreign legal entities as well as their German representative or branch offices. Whether German data protection law applies is determined under section 1. 5.4 Complaint to relevant data protection authority(ies) On what basis are registrations/notifications made? (E.g., per legal entity, per processing purpose, per data category, per system or database.) Each automated processing operation is covered by the notification obligation where this applies. Objection to marketing of personal data, in practice such notification is the exception rather than the rule. The reason is that the general notification requirement does not apply if the data controller has appointed a Data Protection Officer who has the obligation to maintain data protection inventories.

It also does not apply if only up to nine staff process personal data for the data controller’s own purposes on the basis of consent or for the purpose of the creation, performance of termination of a contractual or quasi-contractual relationship with the data subject. In addition to this general right to object, the FDPA contains more specific rights to object to certain types of processing. â– Germany What information must be included in the registration/ notification? (E.g., details of the notifying entity, affected categories of individuals, affected categories of personal data, processing purposes.) Where a notification must be filed, the content of the notification is prescribed in section 4e as: 5.1 In what circumstances is registration or notification required to the relevant data protection regulatory authority(ies)? (E.g., general notification requirement, notification required for specific processing activities.) Although there is a general requirement in section 4 to notify the relevant data protection authority of the automated processing 94 WWW.ICLG.CO.UK name or company name of the data controller; â– owners, management boards, managing directors or other company leaders appointed by law or by the company’s regulations, and the persons in charge of data processing; â– the data controller’s address; â– the purposes of the data collection, processing or use; â– a description of categories of data subjects and the data or categories of data relating to them; â– the recipients or categories of recipients to whom the data can be disclosed; â– standard retention periods for the data; â– intended transfers of the data to third countries; and â– 5 Registration Formalities and Prior Approval â– a general description allowing a preliminary assessment of whether the security measures implemented in accordance with section 9 are appropriate. © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 . Hunton & Williams What are the sanctions for failure to register/notify where required? The sanction for failure to register/notify where required is €50,000 (sections 43(3) and (1) No. 1). 5.6 What is the fee per registration (if applicable)? 6.2 The relevant entity may be fined up to €50,000 and the relevant data protection authority may order it to appoint a Data Protection Officer. 6.3 Generally, there is no notification fee. 5.7 How frequently must registrations/notifications be renewed (if applicable)? The notifications must be updated before the data processing is changed as well as before its termination (section 4e). 5.8 For what types of processing activities is prior approval required from the data protection regulator? Section 4d (5) requires that if automated processing operations are particularly risky for the rights and freedoms of the data subjects, then they must be analysed before any processing starts. This analysis or “prior checking” will be required especially where sensitive personal data are processed or where the processing is intended to evaluate the data subject’s personality, performance or behaviour. It is, however, not required where the processing is required by law, required for the creation, performance of termination of a contractual or quasi-contractual relationship with the data subject or where the data subject has consented. 5.9 Describe the procedure for obtaining prior approval, and the applicable timeframe. The data controller’s Data Protection Officer is responsible for carrying out the prior checking.

He/she must carry out the prior checking after having received an overview of the relevant processing operation from the data controller and can involve the relevant data protection authority as required (section 4d (6)). 6 Appointment of a Data Protection Officer What are the sanctions for failing to appoint a mandatory Data Protection Officer where required? What are the advantages of voluntarily appointing a Data Protection Officer (if applicable)? The majority of businesses in Germany will already have to appoint a DPO by law; therefore, voluntary appointments of DPOs are rare. 6.4 Please describe any specific qualifications for the Data Protection Officer required by law. The DPO must possess the necessary expertise and reliability in order to fulfil his/her responsibilities (section 4f (2)). The German data protection authorities issued more detailed guidance (dated November 4–5, 2010) on what level of qualification and expertise is typically expected.

According to this guidance, all DPOs should have: â– basic knowledge of the personality rights granted by the German Constitution to the customers and employees of the data controller; and â– comprehensive knowledge of the FDPA, including technical (e.g., data security measures) and organisational (e.g., concepts of availability, authenticity and integrity of data) rules. Additional areas of expertise will be required depending on the data controller’s size, industry sector, IT infrastructure and sensitivity of the personal data processed. Furthermore, the Data Protection Officer must be independent within the company and report directly to German management. 6.5 What are the responsibilities of the Data Protection Officer, as required by law or typical in practice? The DPO must work towards compliance with the FDPA and other data protection provisions (e.g., data protection provisions in the Telemedia Act). In particular, the FDPA requires the DPO to undertake the following tasks: Is the appointment of a Data Protection Officer mandatory or optional? There is a general requirement in section 4f (1) to appoint a Data Protection Officer (“DPO”). However, this general notification requirement does not apply if only nine members of staff or fewer process personal data regularly. Nonetheless, a DPO will always have to be appointed if the entity in question uses automated means to processes personal data that are subject to prior checking or for the purposes of commercial data transfer, anonymised commercial transfer or market or opinion research. â– Monitor how data processing software is used to process personal data and verify that the processing is compliant with relevant data protection provisions. â– Take appropriate measures to educate and train individuals processing personal data about the provisions of the FDPA and other relevant data protection provisions. â– If the company is not required to notify its processing to the DPA, the DPO must provide the public data processing inventory to those who request it.

The company must provide the DPO with the data inventory. â– Where a prior checking is required, the DPO is responsible for carrying it out. 6.6 6.1 Germany 5.5 Germany Must the appointment of a Data Protection Officer be registered/notified to the relevant data protection authority(ies)? No, this is not the case. ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London WWW.ICLG.CO.UK 95 . Hunton & Williams 7 Marketing and Cookies Germany 7.1 Please describe any legislative restrictions on the sending of marketing communications by post, telephone, email, or SMS text message. (E.g., requirement to obtain prior opt-in consent or to provide a simple and free means of opt-out.) The Unfair Competition Act generally requires the recipient’s consent if marketing messages are sent to him/her by phone, SMS, fax or email. However, there are exceptions. As regards email, for example, section 7(3) of the Unfair Competition Act allows marketing emails to be sent without the recipient’s consent (therefore opt-out is sufficient) where the following conditions are met cumulatively: â– the company obtained the recipient’s email address from the recipient in connection with the sale of a good or a service; â– the company uses the email address to advertise directly for similar and own goods or services; â– at the time the email address is collected as well as each time it is used, the recipient is informed clearly and unambiguously that he/she can object to such use at any time without incurring transmission costs which exceed the basic transmission tariffs. 7.6 For certain types of marketing activities (e.g., marketing list data), more detailed regulations apply (e.g., section 28 (3)). 7.2 Is the relevant data protection authority(ies) active in enforcement of breaches of marketing restrictions? Yes.

Enforcement action, as well as litigation concerning breaches of marketing restrictions, is frequent in Germany. 7.3 Are companies required to screen against any “do not contact” list or registry? There is no obligation to screen against “do not contact” lists as explicit consent is required in most cases. 7.7 What are the maximum penalties for sending marketing communications in breach of applicable restrictions? Breaches of the Unfair Competition Act’s marketing restrictions can result in fines of up to €300,000 (section 20 (2) of the Unfair Competition Act). 7.5 What types of cookies require explicit opt-in consent, as mandated by law or binding guidance issued by the relevant data protection authority(ies)? There are currently conflicting interpretations of the applicable law. The German government’s position is that only those cookies that are strictly necessary for the user to receive telemedia services (e.g., to view a website) can be used without the user’s prior opt-in consent. The German government’s position is outlined in a communication to the European Commission (COCOM11-20) dated October 4, 2011 and relies on section 15 (1) of the Telemedia Act. The German data protection authorities, however, issued a resolution dated February 5, 2015 in which they request the German government to implement the requirement of the e-Privacy Directive (Article 5 (3)) for opt-in consent for cookies. 96 WWW.ICLG.CO.UK To date, has the relevant data protection authority(ies) taken any enforcement action in relation to cookies? The Bavarian Data Protection Authority (“DPA”) has analysed various web analytics tools in detail and made recommendations on how such tools can be used in a compliant manner. Cookies and opt-out methods played a central role in these analyses. 7.8 What are the maximum penalties for breaches of applicable cookie restrictions? Breaches of the relevant provisions of the FDPA could result in fines of up to €300,000. Breaches of the relevant provisions of the Telemedia Act could result in fines of up to €50,000. 8 Restrictions on International Data Transfers 8.1 Please describe any restrictions on the transfer of personal data abroad? International transfers of personal data subject to German law must pass a two-stage test.

The first stage is whether there is a legal basis for transferring the personal data to a third party since there is no privilege for sharing data within a group of companies. The second stage is whether the personal data will be afforded an adequate level of protection in the country to which they are transferred (section 4b) or whether an exception applies (section 4c). 8.2 7.4 For what types of cookies is implied consent acceptable, under relevant national legislation or binding guidance issued by the relevant data protection authority(ies)? Please refer to the answer above. The position is currently not settled in Germany. the recipient has not objected to such use; and â– Germany Please describe the mechanisms companies typically utilise to transfer personal data abroad in compliance with applicable transfer restrictions. Following the invalidation of Safe Harbour by the European Court of Justice (October 6, 2015), companies still use EU Standard Contractual Clauses to transfer personal data to countries outside the EEA.

For international transfers within a corporate group, Binding Corporate Rules are becoming increasingly common. 8.3 Do transfers of personal data abroad require registration/notification or prior approval from the relevant data protection authority(ies)? Describe which mechanisms require approval or notification, what those steps involve, and how long they take. No. However, the German data protection authorities have the power to authorise individual transfers on an ad hoc basis, where other legal grounds for international data transfer do not apply (section 4c (2)). However, at the time of writing, the German data protection authorities have suspended granting new authorisations for data transfers to the U.S.

(see the German data protection authorities’ position paper dated October 26, 2016). © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 . 9 Whistle-blower Hotlines 9.1 What is the permitted scope of corporate whistleblower hotlines under applicable law or binding guidance issued by the relevant data protection authority(ies)? (E.g., restrictions on the scope of issues that may be reported, the persons who may submit a report, the persons whom a report may concern.) The German data protection authorities have issued formal guidance on the scope of whistle-blowing hotlines (see the data protection authorities’ April 2007 working paper). According to the guidance, the following matters are within the permitted scope: â– any conduct which constitutes a crime and affects the interests of the business. This includes, for example, fraud and fraudulent accounting, corruption, financial crimes, and illegal insider dealing; â– any conduct in breach of human rights. This includes, for example, the use of child labour; and â– any conduct in breach of environmental protection rules. It may also include substantial, serious breaches of lawful and clear company policies but this has to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. The data protection authorities also recommend that companies review whether it is possible to restrict the scope of persons who may submit reports.

They recognise, however, that this requires a case-by-case evaluation. 9.2 Is anonymous reporting strictly prohibited, or strongly discouraged, under applicable law or binding guidance issued by the relevant data protection authority(ies)? If so, how do companies typically address this issue? According to the German data protection authorities’ guidance, anonymous reporting is strongly discouraged. It is recommended that whistle-blowers are informed that their identity will be treated confidentially and that whistle-blowers are not disadvantaged as a result of filing a report. 9.3 Do corporate whistle-blower hotlines require separate registration/notification or prior approval from the relevant data protection authority(ies)? Please explain the process, how long it typically takes, and any available exemptions. Where a company has appointed a Data Protection Officer, there is no requirement to make a notification to the relevant data protection authority. However, it is likely that the Data Protection Officer has to conduct a formal prior check before the whistle-blowing system is deployed.

The length of this prior checking depends on the complexity of the whistle-blowing system and can range from days to months. The Data Protection Officer will also have to update the processing inventories. 9.4 Do corporate whistle-blower hotlines require a separate privacy notice? There is no general requirement to have a separate notice for a whistle-blower hotline. Where works council agreements have been made within the employer’s organisation regarding whistle-blowing Germany which also cover data protection issues, the regulators require the employer to make the content of those agreements easily available to all employees, including new hires.

As the information that needs to be provided to individuals about the whistle-blower hotline is rather specific (e g., description of the procedure for submitting and handling reports, possible consequences of unfounded reports), in practice companies tend to implement a separate privacy notice for their whistle-blower hotline. 9.5 To what extent do works councils/trade unions/ employee representatives need to be notified or consulted? Germany Hunton & Williams Where a works council exists within an organisation, it has to be informed and consulted for any issue related to the implementation of technical means intended to monitor the activities of employees. Regulators advise that companies which plan to implement whistleblowing hotlines better ensure the agreement of their works council in a timely fashion. In practice, companies tend to engage into negotiations with their works councils before implementing whistleblowing hotlines. 10 CCTV and Employee Monitoring 10.1 Does the use of CCTV require separate registration/ notification or prior approval from the relevant data protection authority(ies)? Where a company has appointed a DPO, there is no requirement to make a notification to the relevant data protection authority. However, it is likely that the Data Protection Officer has to conduct a formal prior check before the CCTV system is deployed. The DPO will also have to update the processing inventories. Section 6b regulates in detail how publicly accessible premises may be monitored via CCTV, and the data protection authorities have issued guidelines on CCTV implementation. 10.2 What types of employee monitoring are permitted (if any), and in what circumstances? Employee monitoring is only permitted in very limited circumstances since the relevant legal basis (section 32) is a specific provision for employee data processing.

For example, data controllers may process personal data of employees if it is necessary to discover crimes but only if: (a) there are documented factual indications which support the suspicion that the employee has committed a crime in the course of the employment relationship; (b) the processing of personal data is necessary to discover the crime; and (c) the protected privacy interests of the employee do not take precedence. Permanent monitoring of employees via CCTV is usually not permitted and companies have been fined for doing so. Sporadic monitoring for quality and training purposes (e.g., listening in on customer calls) may be lawful provided it is not excessive and the relevant legal requirements (e.g., notice) are met. 10.3 Is consent or notice required? Describe how employers typically obtain consent or provide notice. In an employment context, data protection authorities consider that consent is not a valid legal basis for the processing of personal data since employees are rarely free to give or withhold consent ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London WWW.ICLG.CO.UK 97 . Hunton & Williams Germany demanded by the employer. Therefore, the employer needs to ensure that any monitoring of employees that involves the processing of personal data is covered by section 32. In addition to the legal basis, the employer must provide advance and sufficiently detailed notice of any employee monitoring. Where the employer has a works council, a works council agreement will usually be required to legitimise the employee monitoring. Employees must then be made aware of these works council agreements, which is usually done via email or another type of prominent notice. 10.4 To what extent do works councils/trade unions/ employee representatives need to be notified or consulted? Section 87 Nos. 1 and 6 of the Works Constitution Act (Betriebsverfassungsgesetz) requires that the works council must be informed about, and agree to, all measures that concern how the employees’ behaviour is regulated and whenever technical means to monitor the employees’ behaviour and performance are to be introduced.

This process usually takes several months. 10.5 Does employee monitoring require separate registration/notification or prior approval from the relevant data protection authority(ies)? Where a company has appointed a DPO, there is no requirement to make a notification to the relevant data protection authority. However, it is likely that the DPO has to conduct a formal prior checking before the employee monitoring measures are deployed. The DPO will also have to update the processing inventories. 11 Processing Data in the Cloud 11.1 Is it permitted to process personal data in the cloud? If so, what specific due diligence must be performed, under applicable law or binding guidance issued by the relevant data protection authority(ies)? Yes, personal data may be processed in the cloud provided all legal requirements are met. In their detailed guidance (dated September 26, 2011), the German data protection authorities identified five areas where specific due diligence by the data controller is required: â– the risk of re-identification of anonymised data; â– the data protection obligations of all parties involved in providing the cloud service (including sub-processors); â– the data controller’s continued ability to comply if a data subject exercises his/her/its rights of access, correction, deletion and blocking; â– the lawfulness of any international transfers of personal data in the context of the cloud services; and â– the presence and verification of appropriate technical and organisational security measures, particularly concerning deletion, data separation, transparency, data integrity, backups and audit functions. Germany 11.2 What specific contractual obligations must be imposed on a processor providing cloud-based services, under applicable law or binding guidance issued by the relevant data protection authority(ies)? The FDPA’s requirements for data processing agreements must be met. These are mainly set out in section 11 and include contractual provisions concerning: â– the subject and duration of the data processing; â– the extent, type and purpose of the intended collection, processing or use of data, the type of data and category of data subjects; â– the technical and organisational security measures to be implemented pursuant to section 9; â– the rectification, erasure and blocking of data; â– the processor’s obligations under section 11 (4), in particular as regards monitoring the data processing; â– any right to appoint sub-processors; â– the data controller’s rights to monitor and the data processor’s corresponding obligations to accept such monitoring and cooperate with the data controller; â– notification obligations where the data processor or its employees breach applicable data protection law or the contract; â– the extent of the data controller’s authority to issue instructions to the data processor; and â– the return of data storage media and the erasure of data recorded by the data processor at the end of the data processing. 12 Big Data and Analytics 12.1 Is the utilisation of big data and analytics permitted? If so, what due diligence is required, under applicable law or binding guidance issued by the relevant data protection authority(ies)? Yes, provided the processing involved in the analysis of the personal data is covered by a legal basis and the remaining provisions of the FDPA (e.g., regarding notice) are complied with. In practice, the Baden-Wurttemberg Data Protection Authority states in its 2013 report that the principles of data minimisation and data economy should be reflected in the design of big data platforms.

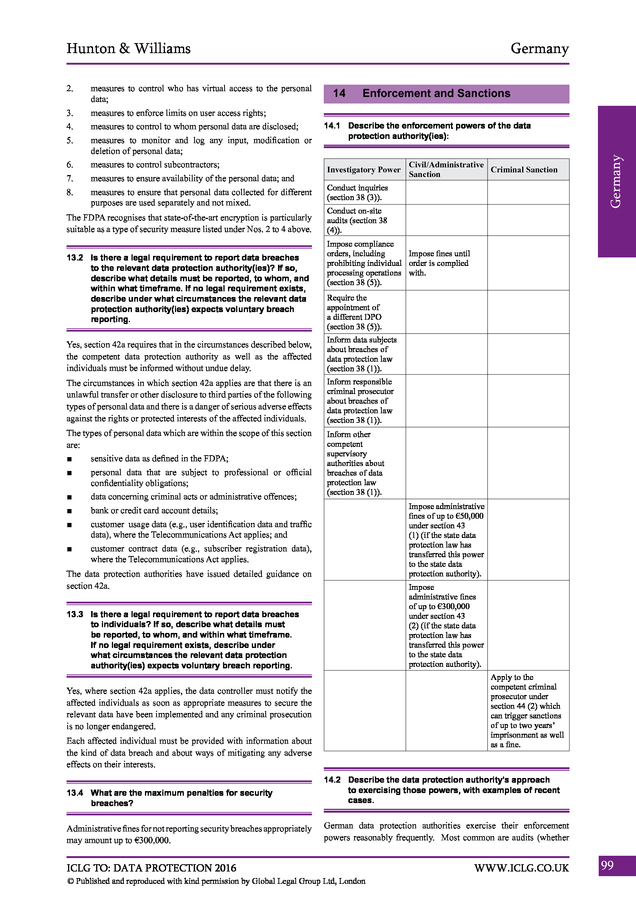

Where anonymisation and pseudonymisation are used, it should be ensured that the risk of re-identification is properly taken into account. 13 Data Security and Data Breach 13.1 What data security standards (e.g., encryption) are required, under applicable law or binding guidance issued by the relevant data protection authority(ies)? Section 9 and its annex set out the legally required data security measures that must be applied when personal data are processed, namely: 1. 98 WWW.ICLG.CO.UK measures to control who has physical access to the personal data; © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 . Hunton & Williams measures to control who has virtual access to the personal data; 3. measures to enforce limits on user access rights; 4. measures to control to whom personal data are disclosed; 5. measures to monitor and log any input, modification or deletion of personal data; 6. measures to control subcontractors; 7. measures to ensure availability of the personal data; and 8. measures to ensure that personal data collected for different purposes are used separately and not mixed. The FDPA recognises that state-of-the-art encryption is particularly suitable as a type of security measure listed under Nos. 2 to 4 above. 13.2 Is there a legal requirement to report data breaches to the relevant data protection authority(ies)? If so, describe what details must be reported, to whom, and within what timeframe. If no legal requirement exists, describe under what circumstances the relevant data protection authority(ies) expects voluntary breach reporting. 14 Enforcement and Sanctions 14.1 Describe the enforcement powers of the data protection authority(ies): Investigatory Power Civil/Administrative Criminal Sanction Sanction Conduct inquiries (section 38 (3)). Conduct on-site audits (section 38 (4)). Germany 2. Germany Impose compliance orders, including Impose fines until prohibiting individual order is complied processing operations with. (section 38 (5)). Require the appointment of a different DPO (section 38 (5)). Yes, section 42a requires that in the circumstances described below, the competent data protection authority as well as the affected individuals must be informed without undue delay. Inform data subjects about breaches of data protection law (section 38 (1)). The circumstances in which section 42a applies are that there is an unlawful transfer or other disclosure to third parties of the following types of personal data and there is a danger of serious adverse effects against the rights or protected interests of the affected individuals. Inform responsible criminal prosecutor about breaches of data protection law (section 38 (1)). The types of personal data which are within the scope of this section are: Inform other competent supervisory authorities about breaches of data protection law (section 38 (1)). â– sensitive data as defined in the FDPA; â– personal data that are subject to professional or official confidentiality obligations; â– data concerning criminal acts or administrative offences; â– bank or credit card account details; â– customer usage data (e.g., user identification data and traffic data), where the Telecommunications Act applies; and â– customer contract data (e.g., subscriber registration data), where the Telecommunications Act applies. Impose administrative fines of up to €50,000 under section 43 (1) (if the state data protection law has transferred this power to the state data protection authority). The data protection authorities have issued detailed guidance on section 42a. Impose administrative fines of up to €300,000 under section 43 (2) (if the state data protection law has transferred this power to the state data protection authority). 13.3 Is there a legal requirement to report data breaches to individuals? If so, describe what details must be reported, to whom, and within what timeframe. If no legal requirement exists, describe under what circumstances the relevant data protection authority(ies) expects voluntary breach reporting. Apply to the competent criminal prosecutor under section 44 (2) which can trigger sanctions of up to two years’ imprisonment as well as a fine. Yes, where section 42a applies, the data controller must notify the affected individuals as soon as appropriate measures to secure the relevant data have been implemented and any criminal prosecution is no longer endangered. Each affected individual must be provided with information about the kind of data breach and about ways of mitigating any adverse effects on their interests. 13.4 What are the maximum penalties for security breaches? 14.2 Describe the data protection authority’s approach to exercising those powers, with examples of recent cases. Administrative fines for not reporting security breaches appropriately may amount up to €300,000. German data protection authorities exercise their enforcement powers reasonably frequently. Most common are audits (whether ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London WWW.ICLG.CO.UK 99 .

Hunton & Williams Germany by way of questionnaire or on-site inspection) as well as specific compliance orders. Where serious breaches occurred or orders are not complied with, German data protection authorities impose fines. Notable cases include a €1.1 million fine imposed on Deutsche Bahn for multiple breaches of the FDPA, as well as a €1.5 million fine imposed on the Lidl group for using private detectives and secret cameras in their German shops. Recent cases concerned Hamburg DPA’s €54,000 fine of Europcar for using GPS trackers in certain rental cars. 15 E-discovery / Disclosure to Foreign Law Enforcement Agencies 15.1 How do companies within your jurisdiction respond to foreign e-discovery requests, or requests for disclosure from foreign law enforcement agencies? In our experience, German companies tend to refer foreign public authorities to the relevant mutual legal assistance treaties so that disclosures of personal data are done in a manner compliant with German data protection law. Where e-discovery requests are concerned, German companies tend to pseudonymise or anonymise the relevant materials first, before they are transferred. 15.2 What guidance has the data protection authority(ies) issued? Where direct disclosure requests/orders by foreign public authorities are concerned, the German data protection authorities have stated that the relevant German authorities should be involved immediately so that the disclosure can be done in accordance with relevant mutual legal assistance treaties (see the Berlin Data Protection Authority’s statement dated November 14, 2008, as well as the German Federal Ministry of Justice’s letter to the Berlin Data Protection Authority dated January 31, 2007). As regards foreign e-discovery requests/orders, the German data protection authorities’ position is that in light of the Article 29 Working Party’s paper on this topic (WP 158) as well as the Hague Convention, there must not be a transfer of personal data abroad before proceedings have been issued (i.e., pre-trial). Once the proceedings are underway, though, personal data can be transferred in pseudonymised form and data such as individual names may be de-pseudonymised as required on a case-by-case basis (see section 11.3 of the Berlin Data Protection Authority’s 2009 report). 16 Trends and Developments 16.1 What enforcement trends have emerged during the previous 12 months? Describe any relevant case law. German courts and DPAs have been increasingly active during the last 12 months.

There have been a number of important cases in various areas which demonstrate that data protection compliance is taken very seriously by the German DPAs and the German courts. Below are a number of examples of recent case law and DPA proceedings. Further, there has been significant legislative activity. a) Case Law â– Applicable Law 100 On January 24, 2014, the Chamber Court of Berlin rejected Facebook’s appeal of an earlier judgment by the Regional WWW.ICLG.CO.UK Germany Court of Berlin in cases brought by a German consumer rights organisation. In particular, the court: (i) enjoined Facebook from, broadly, operating its “Find a Friend” functionality in a way that violates the German Unfair Competition Act; (ii) enjoined Facebook from using certain provisions in (1) its terms and conditions, and (2) privacy notices concerning advertisements, licensing, personal data relating to third parties and personal data collected through other websites; and (iii) mandated that Facebook provide users with more information about how their address data will be used by the “Find a Friend” functionality. Similar to an earlier case against Apple, the German consumer rights organisation successfully argued that German, not Irish, data protection law applied.

Although other German courts have not always accepted this line of reasoning, the court followed it here and, notably, held that a breach of data protection law may also constitute a breach of the Unfair Competition Act. This approach represents a new development in the data protection context. One of the conditions for consumer rights organisations to be able to commence legal proceedings is that there is a violation of the Unfair Competition Act. Therefore, recognising data protection law violations as violations of the Unfair Competition Act arguably makes it easier for consumer rights organisations to bring privacy-oriented cases.

It also can be seen as part of a wider trend to improve the ability of German consumer rights organisations to sue for breaches of data protection law. â– Web Analytics On February 18, 2014, the Frankfurt am Main Regional Court issued a ruling addressing the use of opt-out notices for web analytics tools. The case concerned Piwik web analytics software and its “AnonymizeIP” function. The court held that website users must be informed clearly about their right to object to the creation of pseudonymised usage profiles. This information must be provided when a user first visits the website (e.g., via a pop-up or highlighted/linked wording on the first page) and must be accessible at all times (e.g., via a privacy notice).

Although the website provider in question had enabled an “anonymising” function in Piwik, the court found that pseudonymised usage profiles were being created. To make that determination, the court drew on the Schleswig-Holstein Data Protection Authority (“DPA”)’s detailed analysis of Piwik, as well as the federal German DPA’s formal resolution on web analytics. Notably, the case was brought by a competitor of the website provider who argued that the website provider breached Germany’s Unfair Competition Act.

This case, along with the Bavarian DPA’s reports on Adobe Analytics and Google Analytics, illustrates that web analytics continue to be a “hot topic” in Germany. The case also represents a broader trend in Germany of treating violations of data protection law as breaches of unfair competition law. â– €1.3 million Fine for Violation of Data Protection Law On December 29, 2014, the Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information of the German state Rhineland-Palatinate issued a press release stating that it imposed a fine of €1,300,000 on the insurance group Debeka. According to the Commissioner, Debeka was fined due to its lack of internal controls and its violations of data protection law.

Debeka sales representatives allegedly bribed public sector employees during the eighties and nineties to obtain address data of employees who were on path to become civil servants. Debeka purportedly wanted this address data to market insurance contracts to these employees. The Commissioner asserted that the action against Debeka is intended to emphasise © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 .

that companies must handle personal data in a compliant manner. The fine was accepted by Debeka to avoid lengthy court proceedings. In addition to the monetary fine, the Commissioner imposed obligations on Debeka with respect to its data protection processes and procedures, including a requirement that Debeka’s employees obtain written consent from customers when they disclose their addresses. The insurance group also has appointed 26 Data Protection Officers.

The public prosecutor has initiated criminal proceedings against representatives of Debeka in this matter and those proceedings are ongoing. â– Fines for Inadequate Data Processing Agreement On August 20, 2015, the Bavarian DPA issued a press release stating that it imposed a significant fine on a data controller for failing to adequately specify the security controls protecting personal data in a data processing agreement with a data processor. The DPA stated in the press release that the data processing agreement did not contain sufficient information regarding the technical and organisational measures to protect the personal data. The press release noted that the agreement was not specific enough and merely repeated provisions mandated by law.

According to the German Federal Data Protection Act, data controllers must impose detailed data security measures on data processors in data processing agreements. The text of a data processing agreement must enable the data controller to assess whether or not the data processor is able to ensure the protection and security of the personal data. According to the DPA, the law provides some flexibility for companies to determine which contractual obligations are appropriate for a particular engagement.

The DPA stated that this choice may depend on the data security plan of the data processor and related data processing systems used. In all data processing agreements, however, the following controls must be specified: (1) physical admission control; (2) virtual access control; (3) access control; (4) transmission control; (5) input control; (6) assignment control; (7) availability control; and (8) separation control. â– Fines for Unlawful Transfer of Customer Data as Part of an Asset Deal On July 30, 2015, the Bavarian DPA issued a press release stating that it imposed a significant fine on both the seller and purchaser in an asset deal for unlawfully transferring customer personal data as part of the deal. In the press release, the DPA stated that customer data often have significant economic value to businesses, particularly with respect to delivering personalised advertising. If a company terminates its business, it may sell its valuable economic assets, including customer data, to another company as part of an asset deal.

In addition, insolvency administrators may try to sell the customer data maintained by the business during the insolvency process. According to the press release, the Bavarian DPA fined both the seller and the purchaser for unlawfully transferring email addresses of customers of an online shop. The exact fines were not announced, but the press release mentions that they were fined upwards of five figures. The DPA also stated that transferring customer email addresses, phone numbers, credit card information and purchase history requires prior customer consent or, alternatively, customers must be given prior notice about the intent to transfer such personal data so that they have an opportunity to object to the transfer.

Since the seller and the purchaser failed to obtain customer consent or give the customers an opportunity to object, the DPA found both companies in violation of German data Germany protection law. The DPA also pointed out that both seller and purchaser are “data controllers” and thus have broader responsibilities than data processors under German data protection law. In addition, the DPA stated that it will act similarly in future cases and will fine companies that sell customer data in a non-compliant manner during asset deals. b) Legislative Activity Further, there has been significant legislative activity in the area of enforcement of data protection law by Consumer Protection Organisations.

On December 18, 2015, the German Federal Parliament approved a draft law to improve the enforcement of data protection provisions that are focused on consumer protection. The new law will bring about a fundamental change in how German data protection law is enforced. The draft law enables consumer protection organisations, trade associations and certain other associations to enforce cease-and-desist letters and file interim injunctions in cases where companies violate the newly defined protective data protection provisions for consumers.

The draft law targets data processing practices for the following purposes: 1) advertising, marketing and opinion research; 2) operating credit agencies; 3) creating personality and usage profiles; 4) selling addresses; 5) other data trading activities; and 6) other similar commercial purposes. The draft law will also introduce a requirement that courts must grant the data protection authorities an opportunity to comment before issuing decisions. Germany Hunton & Williams 16.2 What “hot topics” are currently a focus for the data protection regulator? The German DPAs are very active in issuing guidance papers and addressing a variety of “hot topics” from their perspective. Use of Personal Data for Advertising Purposes For example, on December 10, 2013, a German data protection working group on advertising and address trading published new guidelines on the collection, processing and use of personal data for advertising purposes (the “Guidelines”). These new Guidelines cover, among other things, the following: the use of personal data for advertising purposes without the data subject’s consent (so-called “list-privilege”); consent in the context of advertising, including form (written, electronic, double opt-in) and content requirements; and the data subject’s rights with respect to advertising and the timeframes within which data controllers must respond to the exercise of such rights.

Both sets of guidelines represent a significant clarification of the data protection regulations that apply to advertising in Germany. They are relevant to all businesses with German advertising operations, regardless of target audience (business-to-business and business-to-consumer) or advertising channel (email, telephone, mail). Use of CCTV On March 10, 2014, the German Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information and all 16 German state data protection authorities responsible for the private sector issued guidelines on the use of closed-circuit television (“CCTV”) by private companies. The guidelines provide information regarding the conditions under which CCTV may be used and outline the requirements for legal compliance. Use of Apps On June 18, 2014, the German state data protection authorities responsible for the private sector (the Düsseldorfer Kreis) issued guidelines concerning the data protection requirements for app ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London WWW.ICLG.CO.UK 101 .

Hunton & Williams developers and app publishers. The Guidelines (33 pages) were prepared by the Bavarian DPA and cover requirements in Germany’s Telemedia Act as well as the Federal Data Protection Act. Germany â– At this time, the Position Paper discloses that the German DPAs will not issue new approvals for data transfers to the U.S. on the basis of BCRs or data export agreements. â– The Position Paper requests companies to immediately design their data transfer procedures in a way that considers data protection. Companies that would like to export data to the U.S.

or other third countries should also use as guidance the German DPAs’ March 2014 resolutions on “Human Rights and Electronic Communication” and the October 2014 guidelines on “Cloud Computing”. â– In light of the Safe Harbour Decision of the CJEU, the German DPAs call into question the lawfulness of data transfers to the U.S. on the basis of other transfer mechanisms, such as standard contractual clauses or Binding Corporate Rules (“BCRs”). The German DPAs indicate that consent for the transfer of personal data may be a sound legal basis under narrow conditions. In principle, however, the data transfer must not be massive or occur routinely or repeatedly, according to the Position Paper. â– â– To the extent that they become aware, the Position Paper indicates that the German DPAs will prohibit data transfers to the U.S.

that are solely based on Safe Harbour. With respect to the export of employee data and certain third party data, the German DPAs indicate that consent may only be a lawful legal basis in exceptional cases for a data transfer to the U.S. â– The German DPAs request that the legislators grant them a right to file an action in accordance with the CJEU judgment. â– When using their powers under Article 4 of the respective Commission Decisions on the standard contractual clauses of December 2004 (2004/915/EC) and February 2010 (2010/87/ EC) to assess data transfers, the Position Paper indicates that the German DPAs will rely on the principles formulated by the CJEU. In particular, the German DPAs will focus on Nos. 94 and 95 of the judgment, which address recipient countries that compromise the fundamental right of respect for private life and lack respect for the essence of the fundamental right to effective judicial protection. Germany Data Transfers and Safe Harbour On October 26, 2015, the German federal and state data protection authorities (the “German DPAs”) published a joint position paper on Safe Harbour and potential alternatives for transfers of data to the U.S. (the “Position Paper”). The Position Paper follows the ruling of the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) on Safe Harbour and contains 14 statements regarding the ruling, including the following key highlights: â– In the Position Paper, the German DPAs also call upon the European Commission to push for the creation of sufficiently far-reaching guarantees for the protection of privacy during its negotiations with the U.S., including such protections as the right to judicial remedy, data protection rights and the principle of proportionality.

Further, the German DPAs indicate that it is essential to promptly adjust the Commission Decisions on EU model clauses to the requirements of the CJEU decision. To this extent, the DPAs welcomed the deadline of January 31, 2016 set by the Article 29 Working Party. This article presents the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Hunton & Williams or its clients. The information presented is for general information and education purposes.

No legal advice is intended to be conveyed; readers should consult with legal counsel with respect to any legal advice they require related to the subject matter of the article. This article appeared in the 2016 edition of The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Data Protection published by Global Legal Group Ltd, London. www.iclg.co.uk 102 WWW.ICLG.CO.UK © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 . Hunton & Williams Germany Anna Pateraki Germany Hunton & Williams Park Atrium Rue des Colonies 11 1000 Brussels Belgium Tel: +32 2 643 58 28 Fax: +32 2 643 58 22 Email: apateraki@hunton.com URL: www.hunton.com Anna Pateraki has experience in advising multinational clients of all industry sectors on a broad range of EU data protection and cybersecurity matters, including German-related data protection issues. She has particular experience in developing strategies for international data transfers and regularly advises clients on issues such as data breach notification, cloud computing, smart grids, big data and e-discovery. Hunton & Williams’ Global Privacy and Cybersecurity practice is a leader in its field. It has been ranked by Computerworld for four consecutive years as the top law firm globally for privacy and data security. Chambers & Partners ranks Hunton & Williams as the top privacy and data security practice in its Chambers & Partners UK, Chambers Global and Chambers USA guides. The team of more than 25 privacy professionals, spanning three continents and five offices, is led by Lisa Sotto, who was named among the National Law Journal’s “100 Most Influential Lawyers”.

With lawyers qualified in six jurisdictions, the team includes internationally-recognised partners Bridget Treacy and Wim Nauwelaerts, former FBI cybersecurity counsel Paul Tiao, and former UK Information Commissioner Richard Thomas. In addition, the firm’s Centre for Information Policy Leadership, led by Bojana Bellamy, collaborates with industry leaders, consumer organisations and government agencies to develop innovative and pragmatic approaches to privacy and information security. ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London WWW.ICLG.CO.UK 103 . Other titles in the ICLG series include: â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– Alternative Investment Funds Aviation Law Business Crime Cartels & Leniency Class & Group Actions Competition Litigation Construction & Engineering Law Copyright Corporate Governance Corporate Immigration Corporate Recovery & Insolvency Corporate Tax Employment & Labour Law Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Environment & Climate Change Law Franchise Gambling Insurance & Reinsurance International Arbitration â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– â– Lending & Secured Finance Litigation & Dispute Resolution Merger Control Mergers & Acquisitions Mining Law Oil & Gas Regulation Outsourcing Patents Pharmaceutical Advertising Private Client Private Equity Product Liability Project Finance Public Procurement Real Estate Securitisation Shipping Law Telecoms, Media & Internet Trade Marks 59 Tanner Street, London SE1 3PL, United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7367 0720 / Fax: +44 20 7407 5255 Email: sales@glgroup.co.uk www.iclg.co.uk . .

& Federico de Noriega Olea 155 18 New Zealand Wigley & Company: Michael Wigley 19 Norway Wikborg, Rein & Co. Advokatfirma DA: Dr. Rolf Riisnæs & Dr.

Emily M. Weitzenboeck 171 20 Portugal Cuatrecasas, Gonçalves Pereira: Leonor Chastre 182 21 Romania Pachiu & Associates: Mihaela Cracea & Ioana Iovanesc 193 22 Russia GRATA International Law Firm: Yana Dianova, LL.M. 204 23 South Africa Eversheds SA: Tanya Waksman 217 24 Spain ECIJA ABOGADOS: Carlos Pérez Sanz & Lorena Gallego-Nicasio Peláez 225 25 Sweden Affärsadvokaterna i Sverige AB: Mattias Lindberg 235 26 Switzerland Pestalozzi: Clara-Ann Gordon & Phillip Schmidt 244 27 Taiwan Lee and Li, Attorneys-at-Law: Ken-Ying Tseng & Rebecca Hsiao 254 28 United Arab Emirates Hamdan AlShamsi Lawyers & Legal Consultants: Dr. Ghandy Abuhawash 263 29 United Kingdom Hunton & Williams: Bridget Treacy & Stephanie Iyayi 271 30 USA Hunton & Williams: Aaron P.

Simpson & Chris D. Hydak 280 Group Publisher Richard Firth Published by Global Legal Group Ltd. 59 Tanner Street London SE1 3PL, UK Tel: +44 20 7367 0720 Fax: +44 20 7407 5255 Email: info@glgroup.co.uk URL: www.glgroup.co.uk GLG Cover Design F&F Studio Design GLG Cover Image Source iStockphoto Printed by Ashford Colour Press Ltd. April 2016 Copyright © 2016 Global Legal Group Ltd. All rights reserved No photocopying ISBN 978-1-910083-93-2 ISSN 2054-3786 Strategic Partners 164 Further copies of this book and others in the series can be ordered from the publisher. Please call +44 20 7367 0720 Disclaimer This publication is for general information purposes only.

It does not purport to provide comprehensive full legal or other advice. Global Legal Group Ltd. and the contributors accept no responsibility for losses that may arise from reliance upon information contained in this publication. This publication is intended to give an indication of legal issues upon which you may need advice. Full legal advice should be taken from a qualified professional when dealing with specific situations. WWW.ICLG.CO.UK .

Chapter 11 Germany Hunton & Williams Anna Pateraki 2 Definitions 1 Relevant Legislation and Competent Authorities 2.1 1.1 The principal data protection legislation is the Federal Data Protection Act (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz) (the “FDPA”), which was last amended in 2009 and implements into German law the requirements of the EU Data Protection Directive (95/46/EC) (the “Data Protection Directive”). Where no other law is referred to, references in the following responses to “sections” are references to sections of the FDPA. 1.2 Please provide the key definitions used in the relevant legislation: â– “Personal Data” “Personal data” means any information concerning the personal or material circumstances of an identified or identifiable natural person. â– “Sensitive Personal Data” More commonly known as “special categories of personal data”, which refers to information on racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, health or sex life. â– “Processing” “Processing” means the recording, alteration, transfer, blocking and erasure of personal data. Specifically, irrespective of the procedures applied: What is the principal data protection legislation? Is there any other general legislation that impacts data protection? The 16 German federal states have state-level data protection laws. These laws only apply to the public sector in the relevant state. 1.3 1. “recording” means the entry, recording or preservation of personal data on a storage medium in order that they can be further processed or used; Is there any sector specific legislation that impacts data protection? 2. “alteration” means the modification of the substance of recorded personal data; The Telecommunications Act (Telekommunikationsgesetz) contains sector specific data protection provisions that apply to telecommunications services providers such as internet access providers. The Telemedia Act (Telemediengesetz) also contains sector specific data protection provisions that apply to telemedia service providers such as website providers. Specific rules for online marketing (email, SMS, MMS) are set out in the Unfair Competition Act (Gesetz gegen den unlauteren Wettbewerb). 3. “transfer” means the disclosure of personal data recorded or obtained by data processing to a third party either a) through transfer of the data to a third party, or b) by the third party inspecting or retrieving data available for inspection or retrieval; 4. “blocking” means the identification of recorded personal data in order to restrict their further processing or use; and 5. “erasure” means the deletion of recorded personal data. What is the relevant data protection regulatory authority(ies)? There are 17 state data protection authorities which oversee and enforce private and public sector data protection compliance of entities established in their state. The federal data protection commissioner (Bundesdatenschutzbeauftragter) oversees and enforces data protection compliance within the federal public sector (e.g., federal ministries) as well as certain parts of the postal services and telecommunications services providers’ activities. 92 WWW.ICLG.CO.UK “Data Controller” 1.4 â– “Data controller” means any person or body which collects, processes or uses personal data on his, her or its own behalf, or which commissions others to do the same. â– “Data Processor” The FDPA uses the term “data processor” without explicitly defining it.

The closest to a formal definition is section 11 (1), sentence 1 which reads: “If other bodies collect, process or use personal data on behalf of the controller, the controller shall be responsible for compliance with the provisions of this Act and other data protection provisions.” â– “Data Subject” “Data subject” means an identified or identifiable natural person. © Published and reproduced with kind permission by Global Legal Group Ltd, London ICLG TO: DATA PROTECTION 2016 . Hunton & Williams Germany Other key definitions – please specify (e.g., “Pseudonymous Data”, “Direct Personal Data”, “Indirect Personal Data”) purpose if it passes the balancing of interests test, the personal data are publicly available, it is required to safeguard a third party’s lawful interests, it is required to guard against dangers to the state or public, or it is for research purposes which clearly outweigh the data subject’s legitimate interests. â– “Pseudonymous Data” “Pseudonymous data” is not defined. However, “pseudonymising” means replacing the data subject’s name and other identifying features with another identifier in order to make it impossible or extremely difficult to identify the data subject. Personal data can be processed on the basis of section 32 (employment purposes) only if this is necessary for hiring decisions or, after hiring, for carrying out or terminating the employment contract. Employees’ personal data may be processed to detect crimes only if there is a documented reason to believe the data subject has committed a crime while employed and the processing is necessary to investigate the crime following a balancing of interests test. â– Data minimisation Section 3a sets out the principles of data minimisation and data economy. The section states that as little personal data as possible should be collected, processed and used, and data processing systems should be chosen and organised accordingly. Further, personal data should be anonymised or pseudonymised if and when the purpose for which they are processed allows it and provided that the effort involved here is not disproportionate. â– Proportionality The proportionality principle is reflected throughout the FDPA.

It is used both where particular operations vis-à-vis personal data are concerned (e.g., when personal data should be anonymised (section 3a)) as well as in the form of the balancing of interests test to determine whether a particular legal basis applies (e.g., section 28). â– “Direct Personal Data” “Direct personal data” is not defined. â– “Indirect Personal Data” “Indirect personal data” is not defined. â– “Anonymising” “Anonymising” means the alteration of personal data so that information concerning personal or material circumstances cannot be attributed to an identified or identifiable natural person, or so that such an attempt at attribution would require a disproportionate amount of time, expense and effort. 3 Key Principles 3.1 What are the key principles that apply to the processing of personal data? â– Transparency There are two transparency requirements enshrined in the FDPA. The first is set out in section 4 (2). This section states that personal data must be collected directly from the data subject and they may only be collected without the data subject’s involvement if it is legally required or if, broadly, the processing purpose necessitates an indirect collection and this indirect collection passes the balancing of interests test. â– Retention The second transparency requirement is that the data subject be informed about the collection and processing of personal data relating to him or her. Section 35 (2) No.