Description

Synthetic merger could be the

right elective for higher ed

Edward Kleinguetl, Managing Director, National Transaction Integration Team, Transaction Advisory Services

Jennifer Neill, Director, Transaction Advisory Services

Mary Foster, Managing Director, Higher Education

Larry Ladd, Director, Higher Education

The warning bell that 2016 and 2017 will witness increasing closures of four-year private

colleges has been rung by Moody’s. This warning signals the need for heightened

scrutiny of financial sustainability while there is still time for boards and management to

correct the course.

In this heightened competitive environment,

consolidations, mergers and affiliations are now

gaining attention within higher education. On the

corporate front, merger activity has been robust

for the past two years; it has enabled companies

to take advantage of greater scale to lower costs,

increase flexibility, drive innovation and maintain a

competitive advantage. Universities can reap the same

benefits as their corporate counterparts, as well as

increase their differentiation in the marketplace and

avoid closure.

However, to achieve these benefits, colleges and universities must confront the core obstacle — preservation of identity and value. The fear of losing brand identity, sense of unique mission, academic independence and value of alumni’s degrees represents some of the unique concerns of higher education stakeholders, who are alumni, donors, tenured faculty and students, along with the board of trustees — fiduciaries entrusted to ensure mission achievement and financial sustainability. The fear is not unfounded: In a typical merger, an institution can indeed lose control of its identity and cease to exist in its current form. . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed But in many cases, some form of merger is potentially the only way for a college or university to perpetuate its mission, especially for tuition-dependent private institutions confronted with maintaining sufficient net tuition revenue. At a more strategic level, online learning technologies and advancements in cognitive sciences are driving changes in teaching pedagogies that require investments in technology, human capital and facilities. These investments — along with those necessary in student life, student outcomes and new programs — present significant financial challenges and will eventually become competitive barriers to sustained success. Institutions with a limited revenue base will face difficult choices to remain relevant and financially sustainable.

Consider the case of Virginia’s private Sweet Briar College, where the discussion of a merger never came to fruition. The college abruptly announced in spring 2015 that it was closing due to longtime financial challenges that couldn’t be met by cutting salaries and retirement benefits. While this decision to close has since been reversed, the college is still trying to determine an independent path forward. In the for-profit sector of higher education, mergers are not as rare, and they are becoming more common in the public sector in the face of enrollment challenges and higher operating costs.

In the nonprofit higher education sector, we are seeing gradual acceptance and growth in that activity. We believe that a different type of merger option is especially attractive, allowing a university to participate in the tremendous opportunities of shared services while maintaining its identity and mission. Although it is difficult for an institution’s management, faculty and board to see beyond the concerns associated with a typical merger, there are positive aspects to seeking an affiliation partner to garner the benefits of a merger while maintaining institutional identity. The path forward for many institutions may well be a synthetic merger. A different type of merger offers attractive opportunities Synthetic mergers exist in the corporate world, but their potential benefits have been recognized only occasionally in higher education. The synthetic merger model means that to the public, each institution retains its distinct identity, faculty, student population and unique cultural elements, along with its endowments and funding structures.

Behind the scenes, the back-office and support operations are combined to the fullest extent possible, gaining sustainability through economies of scale to reduce costs, expand academic offerings and leverage the leading practices of each institution. These benefits are realized with no change to distinguished and familiar names, and no loss of foundational and endowment support. The participants remain outwardly separate even after their operational integration is complete. An example of a synthetic merger on the corporate side is the consolidation of Air France and the Netherlands’ KLM airline. National brand identities are intact, yet behind the scenes, all systems and support services are fully integrated.

The economies of scale are completely leveraged, even as the two distinct brands are maintained in the market. . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed Consider a hypothetical case University A (UA) is a single-campus private university in the northeastern United States focused predominantly on engineering, design, and commerce. UA is interested in acquiring University B (UB), another single-campus private university located in the same city. UB has a national arts reputation, offering degrees in visual and performing arts, media, design and writing. UA’s leadership feels that broadening its curriculum and footprint would serve the institution well.

UB is perceived to have substantial program assets, so joining forces would better position both institutions for future success. Based on its initial analysis, UA believes annualized operating cost savings can be realized by combining the two institutions. In addition, UA wants to develop an innovative curriculum by following a trend in other engineering and design schools — enhancing traditional science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) curriculums by adding an arts component (science, technology, engineering, arts and math, or STEAM). The prevailing belief at UA is that an arts dimension would increase creativity in more traditional engineering and scientific curriculums, and provide a more innovative learning environment. There are several challenges to be addressed in the merger.

First and foremost is the brand value associated with each institution. UA is regionally but not nationally known. UB has a national reputation and high brand equity.

Thus, there is a compelling reason to retain the UB identity. Another important challenge involves endowments. The endowments cannot be combined, nor can the merger be perceived by either institution’s donors, faculty or alumni as a diminution of their institution’s quality and reputation.

However, the merger could provide significant economic benefits to both. A synthetic merger could solve the quandary. In our hypothetical case, UA and UB will retain their individual identities and associated endowments. Each will maintain its organizational structure, similar to two semiautonomous divisions.

They will determine governance models for the individual institutions and the overarching entity. All activities will be considered; for example, each will retain its own alumni association, and marketing and recruitment programs. UA wants its curriculum to migrate from the traditional STEM to UB’s trending STEAM. At the end of the integration planning process, a changeover to the STEAM curriculum won’t be complete, but the institutions will have a timeline, milestones and actions to sustain the process beyond 100 days after closing.

Subteams will decide about crossregistration, and address registration and system issues (e.g., how courses appear in the catalog). A logistics subteam will evaluate such activities as intercampus bus transportation. Looking ahead, UA is interested in acquiring other institutions. By leveraging the planning process for the merger with UB, UA will create an integration playbook of the transaction’s lessons, with an initial framework of which functions will remain separate, which will be combined, which are subject to a hybrid approach, and how leading practices will be identified.

UA will also establish a true shared-services platform, so future acquisitions will again gain economies of scale and identify appropriate billing/charging systems for discrete services. . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed General M&A principles apply While there are considerable differences between synthetic and typical mergers, the core M&A process remains the same. Perform upfront due diligence: • Financial • Tax • IT • Curriculum • Faculty Develop an integration plan with commonalities, separations and hybrids As in all transactions, the first 100 days post-closing represent the time when organizations are most receptive to change. The pre-closing period is all about building momentum — use that time to develop an effective integration plan that informs an integration model. This model guides the implementation phase, which begins at closing and kicks off the first 100 days. Pre-closing Integration plan • Academic standing • Funding/endowments Integration • Extracurricular activities • Alumni/donors • Facilities/infrastructures Sound and thorough due diligence led by a thoughtful adviser will support the business case and provide foundational information for an integration plan (see timeline). A current affiliation with ‘much to gain’ Two New York institutions are joining forces, collaborating on shared academic offerings, research and funding while retaining separate identities. The president of one school and the dean of the other have issued their optimistic outlook: “It is clear to us that our students and faculties have much to gain from a stronger affiliation between our two schools.1” 1 Albany Law School.

“A Joint Letter from Dean Ouellette and University of Albany President Jones” (press release), May 29, 2015. Post-closing Implementation phase/first 100 days In the development of an integration plan, every functional component of the two institutions is analyzed. The going-in assumption is that certain functional areas (e.g., student billing) will be combined, while other areas will remain separate (e.g., awarding degrees and granting tenure). In addition, the approach for certain functions, such as fundraising, will be further analyzed during the implementation process as the trade-offs between synergies and unique strengths are assessed.

There are three options in the going-forward state: combine, keep separate or create a hybrid. . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed Common platforms can align systems such as registration, websites, electronic blackboards and collaboration sites. While separate sites are maintained for each institution, commonality allows a single IT department to support both. For example, the online enrollment sites would be distinct, yet the underlying platform would be the same. Students would continue to enroll in an individual institution, but a single IT platform would reduce the demand for IT resources. Myriad functions can be brought together into single departments with common support.

These functions can include facilities, real estate, accounting, payroll processing, accounts payable, receivables, tax compliance, treasury, risk management, legal services and procurement. Common support can also extend to vendor contracts, such as food service, security and landscaping. Hybrid sharing can be particularly appropriate in HR. Even if employees remain with separate institutions, processes should be compared to identify best practices. Each institution would hire faculty and grant tenure, but benefit plans could be common and salary bands for noneducator employees could be compared for possible matching.

Associated policies and procedures would be similar or common. Finally, there is the interesting concept of an innovative joint curriculum. While it takes years to fully achieve, the first steps are best set in place during integration planning in order to take advantage of the initial momentum. A dedicated development team is essential, and subteams, such as logistics and crossregistration, can be added as needed.

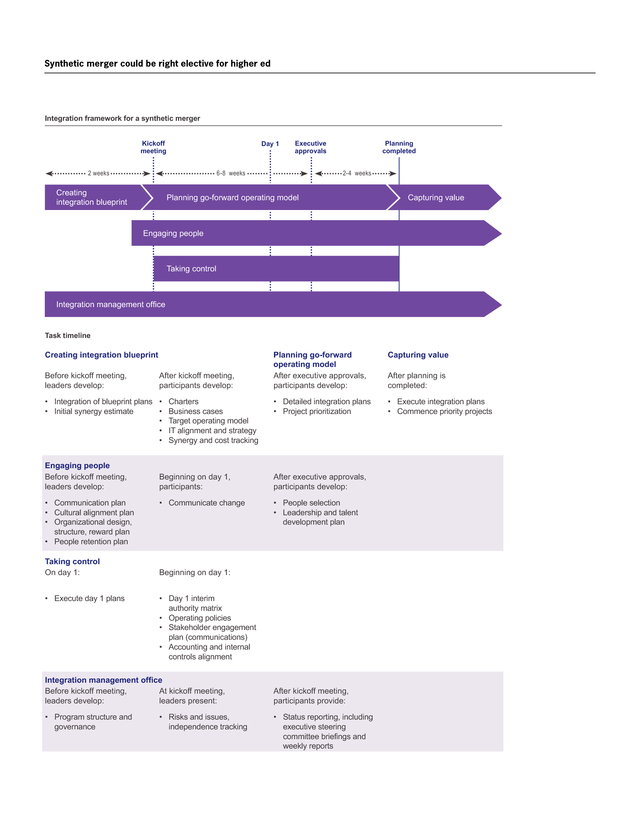

A curriculum initiative must be included as part of the overall integration plan — not independent of it — because the implementation horizon will likely extend beyond the planning phase. This framework can guide you in planning and implementing a synthetic merger. Optimal progression of perspectives • • • • Before the kickoff meeting: “I understand where the value drivers are.” After the kickoff meeting: “I am ready for day 1.” After executive approvals: “I know what will change.” After planning completed: “I can see benefits flowing both to the bottom line and to our students/faculty/institution.” . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed Integration framework for a synthetic merger Kickoff meeting Day 1 2 weeks 6-8 weeks Creating integration blueprint Planning completed Executive approvals 2-4 weeks Planning go-forward operating model Capturing value Engaging people Taking control Integration management ofï¬ce Task timeline Creating integration blueprint Before kickoff meeting, leaders develop: After kickoff meeting, participants develop: • Integration of blueprint plans • Charters • Initial synergy estimate • Business cases • Target operating model • IT alignment and strategy • Synergy and cost tracking Engaging people Before kickoff meeting, leaders develop: • Communication plan • Cultural alignment plan • Organizational design, structure, reward plan • People retention plan Taking control On day 1: • Execute day 1 plans Capturing value • Detailed integration plans • Project prioritization • Execute integration plans • Commence priority projects Beginning on day 1, participants: After executive approvals, participants develop: • Communicate change • People selection • Leadership and talent development plan Beginning on day 1: • Day 1 interim authority matrix • Operating policies • Stakeholder engagement plan (communications) • Accounting and internal controls alignment Integration management ofï¬ce Before kickoff meeting, At kickoff meeting, leaders develop: leaders present: • Program structure and governance Planning go-forward operating model After executive approvals, participants develop: • Risks and issues, independence tracking After kickoff meeting, participants provide: • Status reporting, including executive steering committee briefings and weekly reports After planning is completed: . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed Determine equitable cost sharing A crucial element of successful integration is ensuring that costs are allocated to the appropriate institution. With institutions operating as separate entities but sharing functional support, choose a mechanism for allocating costs to each. Options include a fixed monthly allocation, a variable allocation based on factors such as student enrollment or the number of employees, and direct allocation (e.g., pass-through of third-party costs, such as legal fees). The allocation method should be representative of the underlying cost to provide the services and reasonably easy to calculate on a monthly basis. Economies of scale should result in cost savings. For example, developmental time saved in employee hours will add up as course catalogs and policy manuals are developed just once, with the only difference being the institutional identity. Combining vendor contracts such as security, food service and landscaping should also accrue savings due to greater purchasing leverage. Synthetic mergers offer valuable benefits for preserving your institution’s future.

For key considerations in exploring a synthetic merger, see “When 1 plus 1 is greater than 2” in Grant Thornton LLP’s State of Higher Education in 2015 report (see www.grantthornton.com/highered2015). Contacts Ed Kleinguetl Managing Director National Transaction Integration Team, Transaction Advisory Services T +1 832 476 3760 E ed.kleinguetl@us.gt.com Jennifer Neill Director Transaction Advisory Services T +1 678 515 2325 E jennifer.neill@us.gt.com Mary Foster Managing Director Higher Education T +1 212 542 9610 E mary.foster@us.gt.com Larry Ladd Director Higher Education T +1 617 848 4801 E larry.ladd@us.gt.com This content is not intended to answer specific questions or suggest suitability of action in a particular case. For additional information about the issues discussed, contact a Grant Thornton LLP professional. Connect with us grantthornton.com @grantthorntonus linkd.in/grantthorntonus “Grant Thornton” refers to Grant Thornton LLP, the U.S. member firm of Grant Thornton International Ltd (GTIL), and/or refers to the brand under which the GTIL member firms provide audit, tax and advisory services to their clients, as the context requires.

GTIL and each of its member firms are separate legal entities and are not a worldwide partnership. GTIL does not provide services to clients. Services are delivered by the member firms in their respective countries.

GTIL and its member firms are not agents of, and do not obligate, one another and are not liable for one another’s acts or omissions. In the United States, visit grantthornton.com for details. © 2015 Grant Thornton LLP  |  All rights reserved  |  U.S. member firm of Grant Thornton International Ltd .

However, to achieve these benefits, colleges and universities must confront the core obstacle — preservation of identity and value. The fear of losing brand identity, sense of unique mission, academic independence and value of alumni’s degrees represents some of the unique concerns of higher education stakeholders, who are alumni, donors, tenured faculty and students, along with the board of trustees — fiduciaries entrusted to ensure mission achievement and financial sustainability. The fear is not unfounded: In a typical merger, an institution can indeed lose control of its identity and cease to exist in its current form. . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed But in many cases, some form of merger is potentially the only way for a college or university to perpetuate its mission, especially for tuition-dependent private institutions confronted with maintaining sufficient net tuition revenue. At a more strategic level, online learning technologies and advancements in cognitive sciences are driving changes in teaching pedagogies that require investments in technology, human capital and facilities. These investments — along with those necessary in student life, student outcomes and new programs — present significant financial challenges and will eventually become competitive barriers to sustained success. Institutions with a limited revenue base will face difficult choices to remain relevant and financially sustainable.

Consider the case of Virginia’s private Sweet Briar College, where the discussion of a merger never came to fruition. The college abruptly announced in spring 2015 that it was closing due to longtime financial challenges that couldn’t be met by cutting salaries and retirement benefits. While this decision to close has since been reversed, the college is still trying to determine an independent path forward. In the for-profit sector of higher education, mergers are not as rare, and they are becoming more common in the public sector in the face of enrollment challenges and higher operating costs.

In the nonprofit higher education sector, we are seeing gradual acceptance and growth in that activity. We believe that a different type of merger option is especially attractive, allowing a university to participate in the tremendous opportunities of shared services while maintaining its identity and mission. Although it is difficult for an institution’s management, faculty and board to see beyond the concerns associated with a typical merger, there are positive aspects to seeking an affiliation partner to garner the benefits of a merger while maintaining institutional identity. The path forward for many institutions may well be a synthetic merger. A different type of merger offers attractive opportunities Synthetic mergers exist in the corporate world, but their potential benefits have been recognized only occasionally in higher education. The synthetic merger model means that to the public, each institution retains its distinct identity, faculty, student population and unique cultural elements, along with its endowments and funding structures.

Behind the scenes, the back-office and support operations are combined to the fullest extent possible, gaining sustainability through economies of scale to reduce costs, expand academic offerings and leverage the leading practices of each institution. These benefits are realized with no change to distinguished and familiar names, and no loss of foundational and endowment support. The participants remain outwardly separate even after their operational integration is complete. An example of a synthetic merger on the corporate side is the consolidation of Air France and the Netherlands’ KLM airline. National brand identities are intact, yet behind the scenes, all systems and support services are fully integrated.

The economies of scale are completely leveraged, even as the two distinct brands are maintained in the market. . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed Consider a hypothetical case University A (UA) is a single-campus private university in the northeastern United States focused predominantly on engineering, design, and commerce. UA is interested in acquiring University B (UB), another single-campus private university located in the same city. UB has a national arts reputation, offering degrees in visual and performing arts, media, design and writing. UA’s leadership feels that broadening its curriculum and footprint would serve the institution well.

UB is perceived to have substantial program assets, so joining forces would better position both institutions for future success. Based on its initial analysis, UA believes annualized operating cost savings can be realized by combining the two institutions. In addition, UA wants to develop an innovative curriculum by following a trend in other engineering and design schools — enhancing traditional science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) curriculums by adding an arts component (science, technology, engineering, arts and math, or STEAM). The prevailing belief at UA is that an arts dimension would increase creativity in more traditional engineering and scientific curriculums, and provide a more innovative learning environment. There are several challenges to be addressed in the merger.

First and foremost is the brand value associated with each institution. UA is regionally but not nationally known. UB has a national reputation and high brand equity.

Thus, there is a compelling reason to retain the UB identity. Another important challenge involves endowments. The endowments cannot be combined, nor can the merger be perceived by either institution’s donors, faculty or alumni as a diminution of their institution’s quality and reputation.

However, the merger could provide significant economic benefits to both. A synthetic merger could solve the quandary. In our hypothetical case, UA and UB will retain their individual identities and associated endowments. Each will maintain its organizational structure, similar to two semiautonomous divisions.

They will determine governance models for the individual institutions and the overarching entity. All activities will be considered; for example, each will retain its own alumni association, and marketing and recruitment programs. UA wants its curriculum to migrate from the traditional STEM to UB’s trending STEAM. At the end of the integration planning process, a changeover to the STEAM curriculum won’t be complete, but the institutions will have a timeline, milestones and actions to sustain the process beyond 100 days after closing.

Subteams will decide about crossregistration, and address registration and system issues (e.g., how courses appear in the catalog). A logistics subteam will evaluate such activities as intercampus bus transportation. Looking ahead, UA is interested in acquiring other institutions. By leveraging the planning process for the merger with UB, UA will create an integration playbook of the transaction’s lessons, with an initial framework of which functions will remain separate, which will be combined, which are subject to a hybrid approach, and how leading practices will be identified.

UA will also establish a true shared-services platform, so future acquisitions will again gain economies of scale and identify appropriate billing/charging systems for discrete services. . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed General M&A principles apply While there are considerable differences between synthetic and typical mergers, the core M&A process remains the same. Perform upfront due diligence: • Financial • Tax • IT • Curriculum • Faculty Develop an integration plan with commonalities, separations and hybrids As in all transactions, the first 100 days post-closing represent the time when organizations are most receptive to change. The pre-closing period is all about building momentum — use that time to develop an effective integration plan that informs an integration model. This model guides the implementation phase, which begins at closing and kicks off the first 100 days. Pre-closing Integration plan • Academic standing • Funding/endowments Integration • Extracurricular activities • Alumni/donors • Facilities/infrastructures Sound and thorough due diligence led by a thoughtful adviser will support the business case and provide foundational information for an integration plan (see timeline). A current affiliation with ‘much to gain’ Two New York institutions are joining forces, collaborating on shared academic offerings, research and funding while retaining separate identities. The president of one school and the dean of the other have issued their optimistic outlook: “It is clear to us that our students and faculties have much to gain from a stronger affiliation between our two schools.1” 1 Albany Law School.

“A Joint Letter from Dean Ouellette and University of Albany President Jones” (press release), May 29, 2015. Post-closing Implementation phase/first 100 days In the development of an integration plan, every functional component of the two institutions is analyzed. The going-in assumption is that certain functional areas (e.g., student billing) will be combined, while other areas will remain separate (e.g., awarding degrees and granting tenure). In addition, the approach for certain functions, such as fundraising, will be further analyzed during the implementation process as the trade-offs between synergies and unique strengths are assessed.

There are three options in the going-forward state: combine, keep separate or create a hybrid. . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed Common platforms can align systems such as registration, websites, electronic blackboards and collaboration sites. While separate sites are maintained for each institution, commonality allows a single IT department to support both. For example, the online enrollment sites would be distinct, yet the underlying platform would be the same. Students would continue to enroll in an individual institution, but a single IT platform would reduce the demand for IT resources. Myriad functions can be brought together into single departments with common support.

These functions can include facilities, real estate, accounting, payroll processing, accounts payable, receivables, tax compliance, treasury, risk management, legal services and procurement. Common support can also extend to vendor contracts, such as food service, security and landscaping. Hybrid sharing can be particularly appropriate in HR. Even if employees remain with separate institutions, processes should be compared to identify best practices. Each institution would hire faculty and grant tenure, but benefit plans could be common and salary bands for noneducator employees could be compared for possible matching.

Associated policies and procedures would be similar or common. Finally, there is the interesting concept of an innovative joint curriculum. While it takes years to fully achieve, the first steps are best set in place during integration planning in order to take advantage of the initial momentum. A dedicated development team is essential, and subteams, such as logistics and crossregistration, can be added as needed.

A curriculum initiative must be included as part of the overall integration plan — not independent of it — because the implementation horizon will likely extend beyond the planning phase. This framework can guide you in planning and implementing a synthetic merger. Optimal progression of perspectives • • • • Before the kickoff meeting: “I understand where the value drivers are.” After the kickoff meeting: “I am ready for day 1.” After executive approvals: “I know what will change.” After planning completed: “I can see benefits flowing both to the bottom line and to our students/faculty/institution.” . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed Integration framework for a synthetic merger Kickoff meeting Day 1 2 weeks 6-8 weeks Creating integration blueprint Planning completed Executive approvals 2-4 weeks Planning go-forward operating model Capturing value Engaging people Taking control Integration management ofï¬ce Task timeline Creating integration blueprint Before kickoff meeting, leaders develop: After kickoff meeting, participants develop: • Integration of blueprint plans • Charters • Initial synergy estimate • Business cases • Target operating model • IT alignment and strategy • Synergy and cost tracking Engaging people Before kickoff meeting, leaders develop: • Communication plan • Cultural alignment plan • Organizational design, structure, reward plan • People retention plan Taking control On day 1: • Execute day 1 plans Capturing value • Detailed integration plans • Project prioritization • Execute integration plans • Commence priority projects Beginning on day 1, participants: After executive approvals, participants develop: • Communicate change • People selection • Leadership and talent development plan Beginning on day 1: • Day 1 interim authority matrix • Operating policies • Stakeholder engagement plan (communications) • Accounting and internal controls alignment Integration management ofï¬ce Before kickoff meeting, At kickoff meeting, leaders develop: leaders present: • Program structure and governance Planning go-forward operating model After executive approvals, participants develop: • Risks and issues, independence tracking After kickoff meeting, participants provide: • Status reporting, including executive steering committee briefings and weekly reports After planning is completed: . Synthetic merger could be right elective for higher ed Determine equitable cost sharing A crucial element of successful integration is ensuring that costs are allocated to the appropriate institution. With institutions operating as separate entities but sharing functional support, choose a mechanism for allocating costs to each. Options include a fixed monthly allocation, a variable allocation based on factors such as student enrollment or the number of employees, and direct allocation (e.g., pass-through of third-party costs, such as legal fees). The allocation method should be representative of the underlying cost to provide the services and reasonably easy to calculate on a monthly basis. Economies of scale should result in cost savings. For example, developmental time saved in employee hours will add up as course catalogs and policy manuals are developed just once, with the only difference being the institutional identity. Combining vendor contracts such as security, food service and landscaping should also accrue savings due to greater purchasing leverage. Synthetic mergers offer valuable benefits for preserving your institution’s future.

For key considerations in exploring a synthetic merger, see “When 1 plus 1 is greater than 2” in Grant Thornton LLP’s State of Higher Education in 2015 report (see www.grantthornton.com/highered2015). Contacts Ed Kleinguetl Managing Director National Transaction Integration Team, Transaction Advisory Services T +1 832 476 3760 E ed.kleinguetl@us.gt.com Jennifer Neill Director Transaction Advisory Services T +1 678 515 2325 E jennifer.neill@us.gt.com Mary Foster Managing Director Higher Education T +1 212 542 9610 E mary.foster@us.gt.com Larry Ladd Director Higher Education T +1 617 848 4801 E larry.ladd@us.gt.com This content is not intended to answer specific questions or suggest suitability of action in a particular case. For additional information about the issues discussed, contact a Grant Thornton LLP professional. Connect with us grantthornton.com @grantthorntonus linkd.in/grantthorntonus “Grant Thornton” refers to Grant Thornton LLP, the U.S. member firm of Grant Thornton International Ltd (GTIL), and/or refers to the brand under which the GTIL member firms provide audit, tax and advisory services to their clients, as the context requires.

GTIL and each of its member firms are separate legal entities and are not a worldwide partnership. GTIL does not provide services to clients. Services are delivered by the member firms in their respective countries.

GTIL and its member firms are not agents of, and do not obligate, one another and are not liable for one another’s acts or omissions. In the United States, visit grantthornton.com for details. © 2015 Grant Thornton LLP  |  All rights reserved  |  U.S. member firm of Grant Thornton International Ltd .