Description

Future of the Internet Initiative White Paper

Internet Fragmentation:

An Overview

January 2016

. Future of the Internet Initiative White Paper

Internet Fragmentation: An Overview

William J. Drake

Vinton G. Cerf

Wolfgang Kleinwächter

January 2016

. Contents

Preface

Executive Summary

Introduction

1. The Nature of Internet Fragmentation

The Open Internet

Working Definitions

The Variability of Fragmentation

2. Technical Fragmentation

Addressing

Interconnecting the Network of Networks

The Domain Name System

Security

3. Governmental Fragmentation

National Sovereignty and Cyberspace

Content and Censorship

E-Commerce and Trade

National Security

Privacy and Data Protection

Data Localization

Cybersovereignty

4.

Commercial Fragmentation Peering and Standardization Network Neutrality Walled Gardens Geo-Localization and Geo-Blocking Intellectual Property 5. Conclusions About the Authors Acknowledgements Endnotes 1 3 7 10 10 13 15 20 20 22 24 29 31 31 33 35 37 39 41 45 49 49 50 52 55 56 58 64 66 67 The views expressed in this White Paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the World Economic Forum or its Members and Partners. White Papers are submitted to the World Economic Forum as contributions to its insight areas and interactions, and the Forum makes the final decision on the publication of the White Paper.

White Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and further debate. . 1 Preface The World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2015 in Davos-Klosters included a session entitled, Keeping "Worldwide" in the Web. Participants discussed a number of challenges facing the open global Internet, which has become a key driver of global wealth creation, socio-cultural enrichment and human empowerment in recent decades. Among the top concerns raised was the emerging fragmentation of the Internet along multiple lines due to developments in the technical, governmental and commercial realms. In the months to follow, it became clear that while this fragmentation was of growing concern to many close observers of and participants in the global Internet ecosystem, there was no widespread consensus as to its nature and scope. As such, with the launch of the World Economic Forum’s multi-year Future of the Internet Initiative (FII), Internet fragmentation stood out as one of the priority topics meriting exploration in the context of the FII’s Governance on the Internet project. To facilitate the discussion, the Forum invited William J.

Drake, who had been a discussion leader at the Annual Meeting session, to organize a small team of experts that could produce a background paper on the subject. This team included Vinton Cerf, widely regarded as a “father of the Internet”, and Wolfgang Kleinwächter, a leading figure in global Internet governance institutions. The team’s mandate was to contribute to the emergence of a common baseline understanding of Internet fragmentation by undertaking a horizontal mapping of the issues and dynamics involved.

That is, its intended value-added would be in presenting a big picture overview of a range of examples illustrating the trend towards fragmentation, rather than in offering finely detailed portraits of any of them. From the outset of the process, the World Economic Forum engaged a number of interested participants in the FII’s Core Community, as well as a group of external experts. The research in progress was discussed both at meetings held in Geneva and New York and on conference calls to engage in dialogue and gather feedback, and over a dozen written replies to the draft version were received as well. All these inputs were taken into consideration by the team of authors.

Ultimately though, the views expressed in the paper are solely those of the authors working in their individual capacities, and not necessarily those of their respective organizations, or of the World Economic Forum itself or its Members or Partners. I would like to thank the authors for their intellectual leadership in developing this analysis, which is an important, new resource for everyone concerned about the evolution of the Internet. I would also like to express appreciation to the informal multistakeholder group of experts who reviewed earlier drafts and provided comments to the authors. The Forum particularly wishes to recognize the leadership and support of the trustees and partners of the Global Challenge Initiative on the Future of the Internet, of which this .

2 workstream is a part, as well as the Initiative's Co-Heads, Mark Spelman and Alex Wong, and its Director, Danil Kerimi. As a first-cut overview of the fragmentation landscape, this paper will help to set a foundation for further analyses and action-oriented dialogues among FII participants and within the international community at large. It was commissioned for the explicit purpose of providing a more informed basis for the identification and prioritization by all stakeholders of potential areas of collaboration, including the definition of good practices or policy models that can serve as a constructive example for others. A first step down this path will be taken with the Annual Meeting 2016 session on Internet without Borders. As the title of this session suggests, the Forum’s engagement in this issue area is guided by a conviction that keeping the Internet as open and interoperable as possible is essential if we are to sustain and expand its capacities to promote global well-being in the years ahead. Richard Samans Member of the Managing Board Geneva, January 2016 . 3 Executive Summary A growing number of thought leaders have expressed concerns over the past two years that the Internet is in some danger of splintering or breaking up into loosely coupled islands of connectivity. A number of potentially troubling trends driven by technological developments, government policies and commercial practices have been rippling across the Internet’s layers, from the underlying infrastructures up to the applications, content and transactions it conveys. But there does not appear to be a clearly defined, widely shared understanding of what the term, fragmentation, does and does not entail. The growth of these concerns does not indicate a pending cataclysm. The Internet remains stable and generally open and secure in its foundations, and it is morphing and incorporating new capabilities that open up extraordinary new horizons, from the Internet of Things and services to the spread of block chain technology and beyond.

Moreover, the increasing synergies between the Internet and revolutionary changes in other technological and social arenas are leading us into a new era of global development that can be seen as constituting a fourth industrial revolution. But there are challenges accumulating which, if left unattended, could chip away to varying degrees at the Internet’s enormous capacity to facilitate human progress. We need to take stock of these, and to begin a more structured dialogue about their nature, scope and distributed collective management. The purpose of this document is to contribute to the emergence of a common baseline understanding of Internet fragmentation.

It maps the landscape of some of the key trends and practices that have been variously described as constituting Internet fragmentation and highlights 28 examples. A distinction is made between cases of technical, governmental and commercial fragmentation. The technical cases generally can be said to involve fragmentation “of” the Internet, or its underlying physical and logical infrastructures.

The governmental and commercial cases often more directly involve fragmentation “on” the Internet, or the transactions and cyberspace it conveys, although they also can involve the infrastructure as well. With the examples cited placed in these three conjoined baskets, we can get a holistic overview of their nature and scope and more readily engage in the sort of dialogue and cooperation that is needed. Section 1: The Nature of Internet Fragmentation The open Internet provides a baseline approach from which fragmentation departs and against which it can be assessed. Particularly important are the notions of global reach with integrity; a unified, global and properly governed root and naming/numbering system; interoperability; universal accessibility; the reusability of capabilities; and permissionless innovation. .

4 The conventional four-layer technical model of the Internet can analytically supplemented by the addition of a fifth content and transactions layer. Working definitions are proposed for three forms of fragmentation: Technical Fragmentation: conditions in the underlying infrastructure that impede the ability of systems to fully interoperate and exchange data packets and of the Internet to function consistently at all end points. Governmental Fragmentation: Government policies and actions that constrain or prevent certain uses of the Internet to create, distribute, or access information resources. Commercial Fragmentation: Business practices that constrain or prevent certain uses of the Internet to create, distribute, or access information resources. In each case, fragmentation may vary greatly according to a number of dimensions or attributes. The paper highlights four in particular: • • • • Occurrence: whether a type of fragmentation exists or is a potential Intentionality: whether fragmentation is the result of deliberate action or an unintended consequence Impact: whether fragmentation is deep, structural and configurative of large swaths of activity or even the Internet as a whole, or rather more shallow, malleable and applicable to a narrowly bounded set of processes, transactions and actors Character: whether fragmentation is generally positive, negative, or neutral Section 2: Technical Fragmentation When the Internet concept was first articulated, a guiding vision was that every device on the Internet should be able to exchange packets with any other device. Universal connectivity was assumed to be a primary benefit. But there are a variety of ways in which the original concept has been eroded through a complex evolutionary process that has unfolded slowly but is gathering pockets of steam in the contemporary era. Four issue-areas are reviewed, including Internet addressing, interconnection, naming and security.

Within these categories, 12 kinds of fragmentation of varying degrees of significance are identified: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Network Address Translation IPv4 and IPv6 incompatibility and the dual-stack requirement Routing corruption Firewall protections Virtual private network isolation and blocking . 5 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. TOR “onion space” and the “dark web” Internationalized Domain Name technical errors Blocking of new gTLDs Private name servers and the split-horizon DNS Segmented Wi-Fi services in hotels, restaurants, etc. Possibility of significant alternate DNS roots Certificate authorities producing false certificates Section 3: Governmental Fragmentation The most common imagery of “governmental fragmentation” is of the global public Internet being divided into digitally bordered “national Internets”. Movement in the direction of national segmentation could entail, inter alia, establishing barriers that impede Internet technical functions, or block the flow of information and e-commerce over the infrastructure. Pressure and trends in this direction do exist, as do counter-pressures. Six issue-areas are reviewed, including: content and censorship; e-commerce and trade; national security; privacy and data protection; data localization; and fragmentation as an overarching national strategy. Within these categories, 10 kinds of fragmentation of varying degrees of significance are identified: 1. Filtering and blocking websites, social networks or other resources offering undesired contents 2.

Attacks on information resources offering undesired contents 3. Digital protectionism blocking users’ access to and use of key platforms and tools for electronic commerce 4. Centralizing and terminating international interconnection 5.

Attacks on national networks and key assets 6. Local data processing and/or retention requirements 7. Architectural or routing changes to keep data flows within a territory 8.

Prohibitions on the transborder movement of certain categories of data 9. Strategies to construct “national Internet segments” or “cybersovereignty” 10. International frameworks intended to legitimize restrictive practices Section 4: Commercial Fragmentation A variety of critics have charged that certain commercial practices by technology companies also may contribute to Internet fragmentation.

The nature of the alleged fragmentation often pertains to the organization of specific markets and digital spaces and the experiences of users that choose to participate in them, but sometimes it can impact the technical infrastructure and operational environments for everyone. Whether or not one considers commercial practices as meriting the same level of concern as, say, data localization is of course a matter of perspective. Certainly there are significant concerns from the perspectives of many Internet users, activists and competing providers in global markets.

As such, the issues are on the table in . 6 the growing global dialogue about fragmentation, and they are therefore discussed here. Five issue-areas are reviewed, including: peering and standardization; network neutrality; walled gardens; geo-localization and geo-blocking; and infrastructure-related intellectual property protection. Within these categories, 10 kinds of fragmentation of varying degrees of significance are identified: 1. Potential changes in interconnection agreements 2. Potential proprietary technical standards impeding interoperability in the IoT 3.

Blocking, throttling, or other discriminatory departures from network neutrality 4. Walled gardens 5. Geo-blocking of content 6.

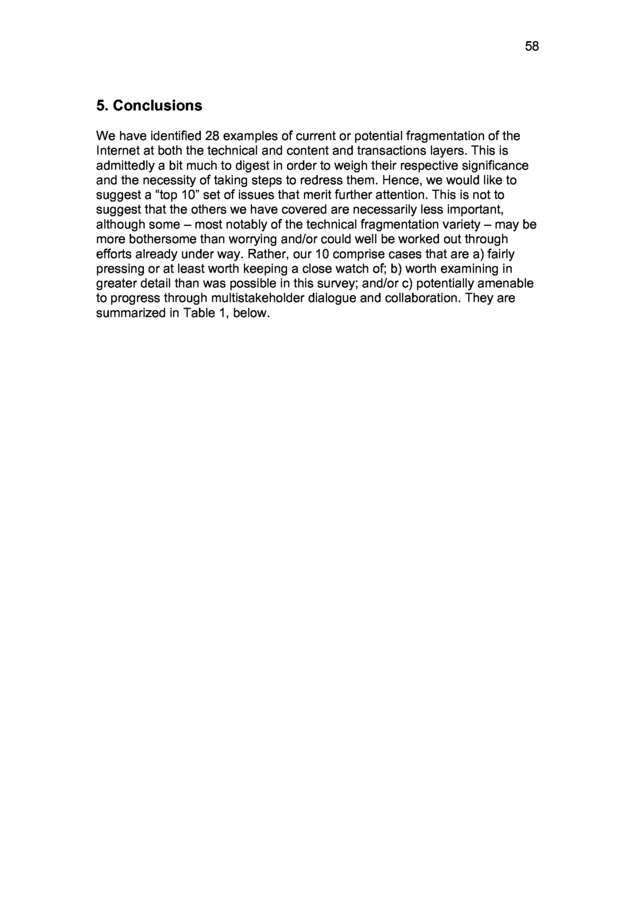

Potential use of naming and numbering to block content for the purpose of intellectual property protection Section 5: Conclusions Drawing on the survey of fragmentation examples, a “top 10” set of cases is suggested that are a) fairly pressing or at least worth keeping a close watch of; b) worth examining in greater detail than was possible in this paper; and/or c) potentially amenable to progress through multistakeholder dialogue and collaboration. These are: • Sustained delays or failure to move from IPv4 to IPv6 • Widespread blocking of new gTLDs • Significant alternate root systems • Filtering and blocking due to content • Digital protectionism • Local data processing and/or retention requirements • Prohibitions on the transborder movement of certain categories of data • Strategies for “national Internet segments” or “cybersovereignty” • Walled gardens • Geo-blocking Taking into account these 10 cases and the preceding discussion, six sets of challenges stand out as being both pressing and particularly amenable to productive analysis and multi-stakeholder dialogue and cooperation: • Fragmentation as Strategy • Data Localization • Digital Protectionism • Access via Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs) • Walled Gardens • Information Sharing . 7 Introduction Internet fragmentation has become a rather hot topic of late. A growing number of thought leaders in government, the private sector, the Internet technical community, civil society and academia have expressed concerns over the past two years that the Internet is in some danger of splintering or breaking up into loosely coupled islands of connectivity. Usually these statements have not been elaborated on at any length, and have offered by way of illustration just a few strains or flash points of tension. Nevertheless, the concern has been picked up and repeated by enough media outlets and mentioned in enough global Internet discussions to transition from a murmur to a near-meme. The most widely noted catalyst for this emerging discourse has been the June 2013 revelations by Edward Snowden regarding mass surveillance.

In the wake of his disclosures, numerous governments began to openly discuss or actively pursue the localization of certain types of data and communication flows within their territorial jurisdictions. But in reality, as significant as these developments have been, they really are only the tip of the iceberg. For some time now, a number of potentially troubling trends driven by technological developments, government policies and commercial practices have been rippling across the Internet’s layers, from the underlying infrastructures up to the applications, content and transactions it conveys. Some of these are of recent vintage, but others are the result of longer-term processes of evolution. The diversity of these trends means that different actors seem to experience and visualize fragmentation differently.

In consequence, there does not appear to be a clearly defined, widely shared understanding of what the term does and does not entail. In a sense, we may be encountering a virtual variant on Miles’s law of bureaucratic policy-making, i.e. “Where you stand depends on where you sit.” For some in the Internet technical community, fragmentation seems to refer in the first instance to such possibilities as multiple and incompatible root zone files and associated naming and numbering systems; suboptimal changes in the routing architecture; the spread of incompatible technical standards; an increasingly problematic transition from IPv4 to IPv6; and so forth. In contrast, for some in the business community, the term seems to refer more to variations in national policies that add to the cost of or even block commercial transactions, and especially to new policies and practices that interfere with the transborder flow of data, cloud services, globalized value chains, the industrial Internet, and so on. For many in civil society, fragmentation seems to refer instead to the spread of government censorship, blocking, filtering and other access limitations, as well as to proprietary platforms and business models that in some measure impede end users’ abilities to freely create, distribute and access information.

Some people even . 8 argue that socio-cultural trends like the increasing linguistic diversity of cyberspace contributes to fragmentation. In short, many people seem to construe fragmentation in ways that reflect their respective experiences and priorities. This situation is not unexpected, given the number and variety of emerging data points suggesting trends towards fragmentation. Nor is it unprecedented; after all, many other core issues involved in Internet governance and policy today remain contested. Consider for example the ongoing debates about the precise meaning of terms like network neutrality, cybersecurity, or the global public interest.

Without shared definitions or at least bounded understandings of what is or is not encompassed by such terms, it can be very difficult to assess emerging trends and the costs and benefits that may be involved, or to evaluate the potential solutions. So we are in a quandary. There is a growing sense in many quarters that this extraordinary technology that has been a critically important source of new wealth creation, economic opportunity, socio-political development and personal empowerment is experiencing serious new strains and even dangers. This is not to say that some sort of cataclysm is anticipated; the Internet remains stable and generally open and secure in its foundations, and it is morphing and incorporating new capabilities that open up extraordinary new horizons, from the Internet of Things and services to the spread of block chain technology and beyond.

Moreover, the increasing synergies between the Internet and revolutionary changes in other technological and social arenas are leading us into a new era of global development that can be seen as constituting a fourth industrial revolution.1 But it is to say that there are challenges accumulating which, if left unattended, could chip away to varying degrees at the Internet’s enormous capacity to facilitate human progress. We need to take stock of these challenges, and to begin a more structured dialogue about their nature, scope and distributed collective management. No centralized or global intergovernmental response is possible or desirable, given the decentralized character of the Internet that is one of its chief virtues. Effective solutions can only be found through inclusive multistakeholder dialogue and cooperation that is informed by shared understandings of the challenges and the stakes. Accordingly, the purpose of this paper is to contribute to the emergence of a common baseline understanding of Internet fragmentation. We map the landscape of some of the key trends and practices that have been variously described as constituting Internet fragmentation and highlight 28 examples. We distinguish between cases of technical, governmental and commercial fragmentation.

The technical cases generally can be said to involve fragmentation “of” the Internet, or its underlying physical and logical infrastructures. The governmental and commercial cases often more directly involve fragmentation “on” the Internet, or the transactions and cyberspace it . 9 conveys, although they also can involve the infrastructure as well. With the examples cited placed in these three conjoined baskets, we can get a holistic overview of their nature and scope and more readily engage in the sort of dialogue and cooperation that is needed. It should be noted that while the authors all have strongly held views about the importance of promoting a secure, stable and integrated Internet consistent with the values of open economies and societies as well as fundamental human rights and freedoms, this paper is not intended to argue a strong authorial viewpoint or to offer policy recommendations. Instead, our modest objective is to facilitate discussion among World Economic Forum participants and others in the global community that may have varying viewpoints in the hope that they will work towards the identification of shared priorities and responses. The paper is organized as follows. Section 1, The Nature of Internet Fragmentation, sets out our approach to the subject.

Section 2, Technical Fragmentation, surveys actual or potential sites of fragmentation in the underlying technological environment that can affect the Internet’s functioning. Section 3, Governmental Fragmentation, considers the evolving tensions between the territorial sovereign state and the transnational Internet and how these have translated into a complex interplay between fragmentation and harmonization in national policies. Section 4, Commercial Fragmentation, turns to the controversies around certain industry practices that some actors view as constituting forms of fragmentation. Finally, Section 5, Conclusions, pulls back from the issue survey to offer some observations and options for further work. .

10 1. The Nature of Internet Fragmentation We begin our inquiry by proceeding in three steps. First, we consider the baseline from which fragmentation is a departure – the open global public Internet. Second, we suggest “working definitions” of technical, governmental and commercial fragmentation that we believe are sufficient to facilitate structured and productive conversation.

Finally, we take note of some of the ways in which instances of fragmentation vary from one another, sometimes considerably. The Open Internet A useful starting point is to consider what we mean by an unfragmented Internet. What is the baseline from which fragmentation departs and against which it can be assessed? From a technical standpoint, the original shared vision guiding the Internet’s development was that every device on the Internet should be able to exchange data packets with any other device that was willing to receive them. Universal connectivity among the willing was the default assumption, and it could be achieved across a network of interconnected networks if the equipment designed by different providers built in interoperability. This means the ability to transfer and make usable data between systems and applications, and it is achieved via the deployment of common technical standards and protocols.2 Such interoperability needs to be to be seamlessly coherent on an end-to-end basis.

It also needs to be consistent, so that a user’s action yields the same response irrespective of the location or service provider involved. Hence, as one leading expert has concluded, from an engineering standpoint, “Fragmentation … encompasses the appearance of diverse pressures in the networked environment that lead to diverse outcomes that are no longer coherent or consistent.”3 These core features of universal connectivity and interoperability between consenting devices, and the same action yielding the same result each time, are fundamental from a design standpoint. Actions or conditions that impair this seamless functioning can thus be said constitute technical fragmentation. But at the same time, this narrow technical definition may be a bit limiting.

It does not by itself capture how people use and experience the technology in order to construct digital social formations and engage in information, communication and commercial transactions, or the sorts of political and economic forces that may impede their abilities to do so. In this context, it is useful to recast the notion of an unfragmented Internet in terms of the “open” Internet. . 11 But what is an open Internet? Here again we can step into a lacuna regarding a foundational and valued principle of Internet discourse, design and policy. Over the years, the term “openness” has been paired with many core elements of the information and communication technology environment – open access, open source, open standards, open architecture, open network, open decision processes, and so on – but sometimes fine grained differences of perspective impede the formation of consensus on clear shared meanings. Often people simply answer the question by listing properties of the Internet that they find desirable, although admittedly this is not necessarily the most systematic or neutral approach. A human rights lawyer, a trade economist and a network engineer might each give the term a special shade of meaning based on their respective priorities and experiences. We cannot attempt to delve deeply into this long-standing question in this paper. For present purposes, it is sufficient to fall back on the approach of listing properties that seem from our vantage points to be integral to a robust conception of “openness“. In its document on “Internet invariants”, the Internet Society has offered a list that is an attractive baseline and is worth quoting at length, in Box 1. Box 1: The Internet Society’s “Internet Invariants” Global reach, integrity: Any endpoint of the Internet can address any other endpoint, and the information received at one endpoint is as intended by the sender, wherever the receiver connects to the Internet.

Implicit in this is the requirement of global, managed addressing and naming services. General purpose: The Internet is capable of supporting a wide range of demands for its use. While some networks within it may be optimized for certain traffic patterns or expected uses, the technology does not place inherent limitations on the applications or services that make use of it. Supports innovation without requiring permission (by anyone): Any person or organization can set up a new service, that abides by the existing standards and best practices, and make it available to the rest of the Internet, without requiring special permission. The best example of this is the World Wide Web – which was created by a researcher in Switzerland, who made his software available for others to run, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Or, consider Facebook – if there was a business approval board for new Internet services, would it have correctly assessed Facebook’s potential and given it a green light? . 12 Accessible – it’s possible to connect to it, build new parts of it and study it overall: Anyone can “get on” the Internet – not just to consume content from others, but also to contribute content on existing services, put up a server (Internet node) and attach new networks. Based on interoperability and mutual agreement: The key to enabling inter-networking is to define the context for interoperation – through open standards for the technologies, and mutual agreements between operators of autonomous pieces of the Internet. Collaboration: Overall, a spirit of collaboration is required – beyond the initial basis of interoperation and bi-lateral agreements, the best solutions to new issues that arise stem from willing collaboration between stakeholders. These are sometimes competitive business interests, and sometimes different stakeholders altogether (e.g. technology and policy). Technology – reusable building blocks: Technologies have been built and deployed on the Internet for one purpose, only to be used at a later date to support some other important function. This isn’t possible with vertically integrated, closed solutions.

And, operational restrictions on the generalized functionality of technologies as originally designed have an impact on their viability as building blocks for future solutions. There are no permanent favourites: While some technologies, companies and regions have flourished, their continued success depends on continued relevance and utility, not strictly some favoured status. AltaVista emerged as the pre-eminent search service in the 1990’s, but has long-since been forgotten. Good ideas are overtaken by better ideas; to hold on to one technology or remove competition from operators is to stand in the way of the Internet’s natural evolution.4 These are all essential aspects of the open Internet environment, and a number of them speak directly to what fragmentation in a broader useroriented and socio-politically attuned sense of the word entails.

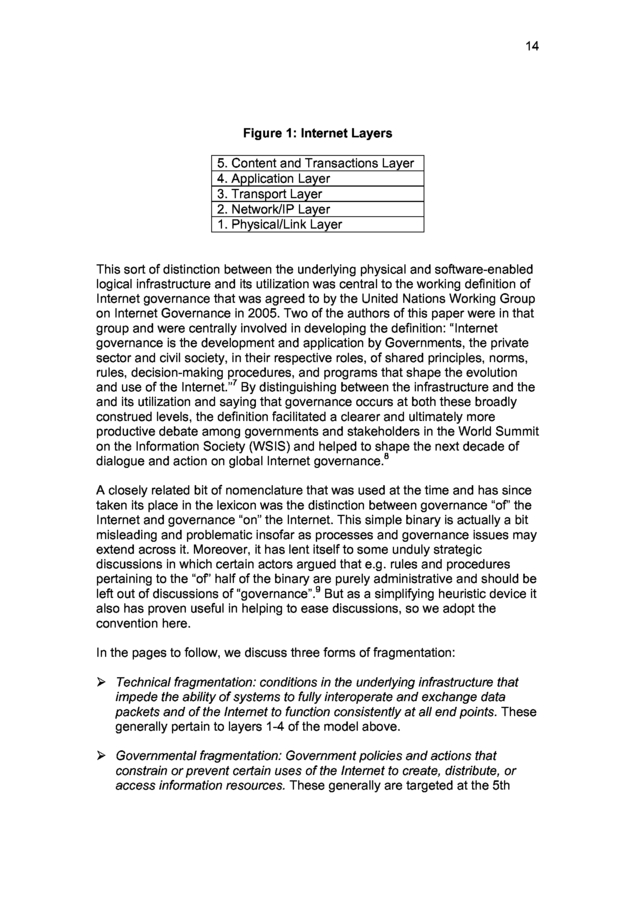

Of particular interest here are the notions of global reach with integrity; a unified, global and properly governed root and naming/numbering system; interoperability; universal accessibility; the reusability of capabilities; and permissionless innovation. An Internet in which any endpoint could not address any other . 13 willing endpoint and have reliably consistent results; and in which digital resources could not be redeployed to an endless variety of user-defined purposes, including the creation of new applications and services, without needing the permission of an intervening authority – this would be a rather fragmented Internet. It would be one that is robbed of what one leading expert calls “generativity”, or the “system's capacity to produce unanticipated change through unfiltered contributions from broad and varied audiences”.5 An open Internet allows creative users to draw on common resources and add to, recombine and customize them in order to design global e-commerce processes and organize value chains, mobilize human rights campaigns, create new products, or socially network with fellow cute cat lovers. Constraints on such usage, in the form of government policies and commercial practices, can cause fragmentation just as much as a technical misfire resulting in inconsistent results. Working Definitions Putting users and their freedoms at the centre of the discussion implies the need for an optic that is wider than just whether the infrastructure effectively connects willing devices anywhere and functions consistently each time at each end. The standard engineering description of the Internet is as a four layered stack of functionalities. The lowest is the physical or hardware link layer over which packets are carried, such as Ethernet, Wireless Wi-Fi, dedicated optical telecommunications circuits, or satellite links.

Moving up the stack, the network or Internet layer is where the Internet protocol (IP) carries packets from a source to a destination, using the routing protocols to determine the paths taken by the packets. Moving further up, the transport layer comprises protocols for various kinds of data transport, such as sequenced and assure delivery of data using the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), or the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) for real-time but not necessarily sequenced or guaranteed delivery. Each IP packet carries an indication of which protocol is to be used to handle the contents or payload of each Internet packet.

Finally, at the top one finds the applications layer where utility protocols such as File Transport Protocol (FTP), Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), Simple Mail Transport Protocol (SMTP), and many others reside. Social analysts often add on top of these four technology layers what they variously call a content, social, or transactional layer to capture the substantive information exchanged and the interactions and behaviours involved.6 In discussing how the Internet is actually used and how that usage may be impeded, the addition of this fifth nominal layer is helpful. The concept could be seen as very roughly analogous to the distinction in traditional telecommunications between network carriage and its content (although in the Internet’s case this is actually too binary a parallel for reasons that need not detain us). Accordingly, in this study we shall refer to a fifth “content and transactions” layer; the resulting scheme is depicted in Figure 1. .

14 Figure 1: Internet Layers 5. Content and Transactions Layer 4. Application Layer 3. Transport Layer 2.

Network/IP Layer 1. Physical/Link Layer This sort of distinction between the underlying physical and software-enabled logical infrastructure and its utilization was central to the working definition of Internet governance that was agreed to by the United Nations Working Group on Internet Governance in 2005. Two of the authors of this paper were in that group and were centrally involved in developing the definition: “Internet governance is the development and application by Governments, the private sector and civil society, in their respective roles, of shared principles, norms, rules, decision-making procedures, and programs that shape the evolution and use of the Internet.”7 By distinguishing between the infrastructure and the and its utilization and saying that governance occurs at both these broadly construed levels, the definition facilitated a clearer and ultimately more productive debate among governments and stakeholders in the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) and helped to shape the next decade of dialogue and action on global Internet governance.8 A closely related bit of nomenclature that was used at the time and has since taken its place in the lexicon was the distinction between governance “of” the Internet and governance “on” the Internet.

This simple binary is actually a bit misleading and problematic insofar as processes and governance issues may extend across it. Moreover, it has lent itself to some unduly strategic discussions in which certain actors argued that e.g. rules and procedures pertaining to the “of” half of the binary are purely administrative and should be left out of discussions of “governance”.9 But as a simplifying heuristic device it also has proven useful in helping to ease discussions, so we adopt the convention here. In the pages to follow, we discuss three forms of fragmentation: Ø Technical fragmentation: conditions in the underlying infrastructure that impede the ability of systems to fully interoperate and exchange data packets and of the Internet to function consistently at all end points.

These generally pertain to layers 1-4 of the model above. Ø Governmental fragmentation: Government policies and actions that constrain or prevent certain uses of the Internet to create, distribute, or access information resources. These generally are targeted at the 5th . 15 layer in our model, but they may involve actions taken at the lower technical layers as well. Ø Commercial fragmentation: Business practices that constrain or prevent certain uses of the Internet to create, distribute or access information resources. These generally are targeted at the 5th layer in our model, but they may involve actions taken at the lower technical layers as well. We should note that some other observers refer to social or cultural forms of fragmentation. In this paper we do not treat the existence of different cultures, languages, social preferences, and so on as sources of fragmentation. They are simply sources of difference.

They may be relevant if, for example, cultural sensibilities lead a government to undertake an action that is fragmentary, but we do not view them as independently causal of fragmentation. In addition, in addressing the roles of governments, we do not attempt to separately delve into what some call “legal fragmentation” due to the existence of different national legal systems.10 The arguments for or against treating legal differences in this manner are best left to those in the legal profession. Again, ours are working definitions proposed to facilitate discussion, and they may be fine-tuned or thoroughly rethought as the emerging dialogue on fragmentation unfolds. But for now they seem to approximately meet some key criteria for such definitions.

These include: adequacy, or being “good enough’ to capture the main meanings that seem to be in play when people discuss fragmentation; generalizability, or applicability across a broad range of current and potential conditions; conciseness, in that they do not appear to include nonessential terminological verbiage; and neutrality, in that they are not intrinsically normative. It should be emphasized that while in the pages to follow we discuss the three types sequentially on a stand-alone basis, this is a convenience intended to reduce narrative complexity. In many cases, the driving considerations at work pertain to the content accessed and transactions undertaken by users, rather than by a desire to alter the infrastructure per se. For example, governments typically are focused on what happens at the top 5th layer of content and transactions rather than on how the lower layers operate.

Even so, the pursuit of remedies to perceived problems in Internet usage often does lead them to take actions that directly or indirectly impact the underlying infrastructure. In some cases, the same may be said of commercial fragmentation. Here as elsewhere, the nominal boundary between fragmentation “of” and fragmentation “on” the Internet can be blurred. The Variability of Fragmentation As our trichotomy of technical, governmental and commercial fragmentation indicates, fragmentation is not singular in its sources or forms.

But the . 16 complexity of the matter does not end there. Within and across the three categories there can be a great deal of variation in its character. Indeed, one could devise a long list of attributes according to which any given instance of fragmentation may vary. To make the discussion more manageable, we highlight just four dimensions of variation that are applicable to our categories and the universe of examples we present in subsequent sections of the paper. Occurrence The first and most fundamental consideration is whether a given form of fragmentation exists.

This is not an entirely straightforward question; fragmentation is not always a simple binary condition that is either present or not present. There can be gradations with different values along a continuum. In some cases those values can be precisely quantified (e.g. the number of websites or other information resources to which access is fully blocked), but in others the best we can do is to devise ordinal measures. Similarly, there can be variations in duration.

Fragmentation may be a shortterm phenomenon that is rectified fairly quickly, as with recovery from some disabling cyberattacks, or it can be sustained as a long-term condition. In time sensitive situations, even short-term fragmentation can be very damaging to users or transactions. In general though, presumably we should be most concerned with sustained fragmentation with recursive consequences. A final issue here is that fragmentation does not need to be currently present to be of concern.

That is, in many of the instances that people cite when worrying about the matter and that we discuss in the sections to follow, what is at stake is the emergence of tendencies and pressures that could give rise to something significant in the future. As in any policy arena, we need not wait for a problem to become full blown and wreaking havoc for awareness and action to be well advised. Intentionality Fragmentation may be the unintended by-product of decisions and actions guided by unrelated objectives. A number of instances of technical fragmentation are of this character.

People who deploy or fail to deploy a particular technology in addressing a localized operational challenge may not be setting out to fragment the Internet. Nevertheless, their actions, especially if replicated by others, could come to have broader effects. Divergences between individually rational choices and systemically suboptimal consequences are a standard feature of collective actions problems generally and the same logic can apply to the openness or fragmentation of the Internet. .

17 Alternatively, fragmentation may be intentional. The character of these intentions obviously matters quite a bit. On the one hand, organizations, communities and individuals may seek to separate themselves somewhat from the open public Internet for entirely defensible reasons. Installing a firewall to limit access and communication to only authorized and consenting parties and to protect resources from unwanted interference is a benign act of self-separation.

On the other hand, actors such as some governments may seek to shape, constrain or fully block the activity of others who have not consented to this. Imposing limitations on others is a malign act of forced separation. Both unintentional and intentional fragmentation can be problematic, but the best approach to remediation may vary accordingly.

In some cases awareness raising, dialogue and coordination may be sufficient, but in others negotiations and even the application of pressure may be called for. Impact Fragmentation may be deep, structural and configurative of large swaths of activity or even the Internet as a whole. Consider, for example, the implications if significant categories of data flows were to be widely blocked around the world, or if an alternative root system with its own address and name space were to be established with the backing of powerful governments or organizations. The scope of the processes, transactions and actors impacted by such breakage would be substantial.

But fragmentation also can be more shallow, malleable and applicable to a narrowly bounded set of processes, transactions and actors. The impact could be significant for some people but go unnoticed by others. As with the other dimensions just mentioned, it can be difficult to measure the intensity of fragmentation and say with certainty exactly where on the continuum a given instance lays. Even so, in considering examples, we should be mindful that fragmentations are not all created equal in terms of magnitude and import.

Indeed, a number of the examples we discuss are relatively low-impact or low-intensity matters – bothersome and concerning enough to engineers and operators that attention to them is merited, but not so significant that they endanger the fundamental integrity, openness and utility of the Internet. In contrast, some other examples we cover are higherimpact and arguably in need of concerted responses. Character Finally, irrespective of the strength of impact, duration, and so on, fragmentation also can vary along a continuum of, for lack of better words, “good” to “bad”. This is an admittedly squishy and difficult to measure attribute, but it captures something important because the tenor of the debate could easily lead one to believe that fragmentation is always and everywhere a bad thing.

But of course, organizations, communities and individuals choose . 18 all the time not to be perfectly reachable from all other end points. The widespread prevalence of firewalls, encryption and other security and privacy tools that allow users to carefully mediate their boundaries and decide which data they welcome to flow across these indicates that fragmentation also can be benevolent and valued. Of course, whether something is viewed as good or bad can depend on norms and value judgments; a human rights defender may regard the dark web as a relatively safe place to communicate and thus a good sort of fragmentation, while a law enforcement or intelligence person may regard it differently. Indeed, people can even have different views about whether significant, structural fragmentation is necessarily a bad thing. Most notably, Columbia University economist Eli Noam has elicited much debate with a short but suggestive broadside against those who argue that fragmentation is inherently bad; see the selection in Box 2. Box 2: A Contrarian View Instead of mourning about the passing of uniformity, we should embrace the emergence of diversity. We must get used to the idea that the standardized Internet is the past but not the future.

And that the future is a federated Internet, not a uniform one. I used to think that this was regrettable but unavoidable. Even that upsets many people: how can one doubt the integrity of the one Internet that has served us so well? Now, I want to go one step further to argue that it is not regrettable at all.

It is actually a good thing. The single Internet was a good system in the past but not in the future …. A technical centrifugalism is inevitable. It is especially inevitable if it becomes readily possible to interoperate among different Internet flavours.

To provide such interoperability across non-uniform protocols are intermediaries that supply ‘bridging as a service’. These intermediaries are likely to be some of the emerging cloud computing providers … Most will be private, but some will be public and governmental. The ITU [International Telecommunication Union], too, could initiate such a cloud …. The emergence of such a system of interconnected private Internet arrangements does not negate a public Internet. On the contrary, the two arrangements supplement each other.

If private Internet arrangements are too restrictive, costly or discriminatory, the public system provides a safety valve, and vice versa. This will prevent such a system from becoming a walled garden of walled gardens, which would be unacceptable.11 . 19 This is, to be sure, a controversial view. But it raises a range of interesting questions about the overall evolution of the Internet as it becomes ever more ubiquitous and embedded in complex and diverse social orders; under what conditions might which forms of fragmentation be benevolent or pernicious; whether fragmentation is sometimes an inevitability to be managed and adapted to as best we can or is instead always a function of short-sighted decisions that should be questioned and remediated; and so on. Conclusion In this section we have sketched out our general analytical orientation to the problem of Internet fragmentation and proposed for working purposes three basic definitions that cover the universe of current and potential cases we have considered. In the next three sections we map out that universe. . 20 2. Technical Fragmentation When the Internet concept was first articulated, a guiding vision was that every device on the Internet should be able to exchange packets with any other device. Universal connectivity was assumed to be a primary benefit. One could not know when such connectivity might prove useful and to exclude any seemed self-defeating. It was further assumed, however, that no device could or should be compelled to engage in communication and that a recipient of a packet could reject or ignore it or impose certain requirements on any further communication. There are a variety of ways in which the original concept of a fully connected Internet has been eroded over the course of the Internet’s over 30 years of operation.

Technical fragmentation of the underlying physical and logical infrastructure is a complex evolutionary process that has unfolded slowly but is gathering pockets of steam in the contemporary era. Some of it has been intentional and motivated by operational and other concerns, and some of it has been the unintended by-product of actions taken with other objective in mind. Moreover, the means by which such fragmentation has been achieved also varies in technical terms.

To capture these realities, in this section we survey some key trends with respect to addressing, interconnection, naming and security in the Internet. Addressing The original design of the Internet used 32 bit numerical identifiers, analogous to telephone numbers, to designate end points on the Internet. Unlike the telephone numbering plan, however, IP addresses were not nationally-based. Their structure was related to the way in which the networks of the Internet were connected. Each network was made up of a collection of IP addresses associated with an autonomous system number.

An endpoint on a given autonomous system or network could be anywhere on the globe, but endpoints of a particular autonomous system are all interconnected through that network. The IP suite went through four major design iterations and the final form for the IP addressing was called IPv4. The 32 bit addresses were represented as four decimal values separated by periods such as 27.2.18.155. Each field has a value ranging from 0 to 255 (i.e.

values that can be expressed in eight binary bits). This address format allowed for up to 4.3 billion possible terminations on the Internet. This so-called dotted notation does not reflect any hierarchical structure – it is merely a convenient way to express a 32 bit number. Coordination of the numbering system is one of the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) functions.

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) currently performs the IANA functions, on . 21 behalf of the US government, through a contract with the National Telecommunications and Information Administration.12 ICANN allocates blocks of numbers to the five Regional Internet Registries (RIRs), which are non-profit corporations that administer and register the IP address space numbers within their regions.13 The global multistakeholder community is currently hard at work on a plan to transition the US government’s stewardship of the IANA functions to a newly independent and accountable ICANN, hopefully in 2016. As the Internet was deployed commercially, it became apparent that there might not be enough numbers to serve all the possible terminations on the growing Internet. This realization triggered two developments. The first was the creation of private numbering plans that allowed for local use of IP addresses that could not be routed through the public Internet. Three distinct private address spaces allowed for networks of up to 256 devices, 32,384 and 16 million devices respectively.

In order to allow local devices to communicate with other devices on the public Internet, these private addresses have to be translated into addresses that are routable in the public Internet. This is the second development associated with IP address limitations. The process is called Network Address Translation (NAT) and it has become widely used to allow many local devices to share a single, public IP address. There is economic incentive for Internet service providers (ISPs) to implement this mechanism so as to maximize the number of subscribers whose devices can be serviced. This process introduces the possibility of a kind of fragmentation in the Internet because the private addresses are isolated from the rest of the Internet unless they pass through a so-called NAT box (that could be part of a router).

In some cases, this isolation may, in fact, be an attractive feature of the NAT mechanism, in addition to the fact that a subscriber who is using private IP addresses does not have to renumber all his or her devices when changing to a new ISP since the NAT process takes care of the mapping into publicly routable addresses when needed. Recognizing the potential depletion of the IPv4 address space, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) that develops international standards for the Internet introduced a new address format called IPv6. This packet format allows for a 128 bit address space, sufficient to label 340 trillion trillion trillion endpoints in the public Internet. The expansion of address space comes with a price, however, because the two formats, IPv4 and IPv6, are not compatible.

It is necessary to run the IPs in parallel in what is called dualstack mode. At present, only about 4% of the Internet is servicing IPv6 usage. There have been signs of late of growing momentum in IPv6 adoption, but clearly there is still a long way to go.14 To make matters worse, most of the RIRs that assign IP address space to ISPs and other end users have essentially exhausted their supplies of IPv4 addresses and have only IPv6 address space to assign. . 22 A market for IPv4 address space has developed but this can only postpone the inevitable need for more addresses. Even the use of NAT will not really prove adequate to serve the enormous anticipated needs of the Internet of Things. In addition, new computer chipsets and cloud computing environments allow for many virtual machines to operate on a single chip, leading to the need for multiple addresses to distinguish among the virtual systems. The fragmentation risk is that the transition to IPv6 will continue to lag and result in IPv4 and IPv6 Internets that do not interwork. ISPs are being encouraged to implement both IPv4 and IPv6 services and end device makers are being encouraged to implement dual-stack IPv4 and IPv6.

It remains to be seen whether these remedies will keep the Internet fully connected, with IPv6 being the eventual address format of choice in the longer term. There are other special addresses ranges for multicasting, that is, sending packets to more than one recipient at a time. One variation on this is the socalled Anycast mechanism that allows computers in many physical locations in the Internet to receive traffic destined for a particular address and respond to it. This is in use in the Domain Name System (DNS), discussed below. Interconnecting the Network of Networks The routing of traffic in the Internet is accomplished by means of routing protocols used by routers to share information about the topology of the connections among the myriad networks that make up the Internet.

An autonomous system is a set of networks and routers that form a connected whole. The Internet is made up of many such autonomous systems. The routers of any particular system use one of several possible interior gateway protocols to establish the connectivity of the system.

Each router within an autonomous system maintains a table of information that allows it to determine the next hop for a packet in a path through the routers of the system until it reaches its destination in that system or arrives at what is called a border router or gateway to the next autonomous system along the packet’s path to the ultimate destination. The topology of the global network of autonomous systems (i.e. the Internet) is maintained through the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) that allows the ensemble of border routers to determine how to route packets. There is a good deal of trust involved in this system and it is possible to inject false information into the routing system to cause packets to flow along paths not expected by the originator.

Each autonomous system’s border routers announce the Internet addresses that can be reached within that system and the BGP protocol allows all the border routers to form a global routing table. Although a good deal of attention is paid by the operators of the networks of the Internet to the possibility that false or incorrect information may be . 23 inserted into the global routing table, it is still technically possible for deliberate or accidental corruption of the routing data to occur. Traffic can be routed into so-called black holes, for example, or along paths that allow surveillance. Technical means have been proposed to defend against such occurrences but they have not yet matured into use. The operators of networks of the Internet determine on their own with which other networks they will interconnect and on what terms and conditions. There are several forms of interconnection.

One form is called peering, in which a pair of networks connect directly with each other or through an Internet Exchange Point (IXP). It is typical that network peering is settlement free in the sense that the parties do not charge each other for carrying traffic, having concluded that they are receiving comparable value as a consequence of the mutual carriage. In a peering relationship, each ISP carries the other’s traffic but only to subscribers of the carrying ISP, not to the ISP’s other peers. There is a second alternative connection method called transit in which one network pays the other to carry its traffic into the rest of the Internet.

This is a typical outcome when a smaller ISP chooses to pay for service to all points of the Internet rather than building additional resources to establish sufficient peering connections to reach all of the Internet. The transit ISP delivers the received traffic to its customers and to all its peers. In practice, many ISPs make use of both methods.

There is also a hybrid form of interconnection called paid peering in which the operators agree to carry each other’s traffic to their respective customers but one ISP pays the other. To date the system of private interconnection contracts among ISPs has ensured the provision of an integrated global public Internet. It is important to ensure that this is preserved even if the incentives to some operators begin to change in ways that could lead to increased costs and fragmentation; we return to this question in Section 4 of this paper. As the Internet became a commercial service and was adopted by the private sector, legitimate interest in protecting computing assets from access by the “outside world” led to the design and implementation of firewalls that could filter traffic at the packet level. Certain protocols could be blocked, port numbers filtered, and even certain source or destination IP address ranges might be allowed or disallowed.

This kind of filtering can be implemented in routers and in edge devices including personal computers. As the Internet of Things (IoT) becomes more prominent, considerable attention may be paid to white listing and strong authentication to protect devices, their controls and their information from unauthorized access. Experience with firewalls has shown them to be insufficient for protection. One can physically walk past a firewall, bringing an infected laptop or memory stick into an enterprise and spread viruses and worms among the computers that are part of the internal enterprise network. Firewalls are, however, a .

24 useful complement to other methods of protection. It seems fair to say that this is a positive form of fragmentation intended to protect enterprise or personal resources from unwanted connections. The IPs allow for a virtual private network (VPN) service in which an ISP allows a customer to tunnel through its part of the Internet to a destination network. The VPN customer receives an IP address that makes it look as if it is part of the destination network connected through a typically encrypted tunnel through a part of the public Internet. Users of VPNs isolate themselves from the global Internet and behave as if they are part of the target network. Corporations with private networks connected to the Internet often use VPN tunnelling to support their employees who need to access corporate assets without exposing these to connection by general users of the Internet.

It might be argued that this capability represents a form of fragmentation. What is perhaps more of concern is that some national jurisdictions are blocking the use of the VPN protocols to prevent users from protecting their traffic from surveillance. In actual fact, VPNs are losing some favour since a compromised laptop or desktop computer with a VPN connection to a corporate network may become the avenue for reaching the assets of the corporate network.

Other means of end/end encryption and authentication are gaining favour. In a variation on the VPN, there is the so-called TOR network or “onion space” that allows users to route traffic randomly through a network of forwarding nodes partly to obscure the originator of the traffic and to obscure the intended destination of the traffic to surveillance until it reaches its last hop. Typically, the traffic is encrypted for privacy until it reaches its destination. Ironically, TOR was originally developed by the US Naval Research Laboratory for use by the intelligence community for exfiltration of information and was later made openly available.

It is widely employed by human rights activists and others with legitimate reasons to avoid government surveillance. But it also is the home of a “dark web” of illegal activities and thus poses challenges to law enforcement and intelligence operations.15 This well illustrates the double-edged sword of the technologies of the Internet. The Domain Name System For flexibility, the protocols above the TCP/IP layer make use of domain names rather than numerical IP addresses to refer to sources and sinks of Internet traffic. Example.com is a domain name whose top-level domain is “com” and whose second-level domain is “example”.

Domain names are essentially synonymous with the notion of a logical end point on the Internet: a client, server or edge computing device of some kind. Before higher-level protocols can make use of the lower-level protocols such as TCP or UDP, they must use the DNS to translate from the domain name form to a numerical IP address form. These applications perform a domain name .

25 lookup using a system of resolvers and name servers that form the hierarchical DNS. The top-level information of the DNS is called the root zone and it points to the name servers for the top-level domains (TLDs) of the Internet, of which there are now on the order of 1,200. They include the familiar “.com”, “.net” and “.org” and country codes such as “.us”, “.fr” and “.jp” and now hundreds of new top-level domains including “.restaurant”, “.pharmacy” and “.capetown”.16 In addition to being easier to remember, domain names have the property that then can be translated into one or more IP addresses, and those addresses can be changed without changing the domain name. This means that persistent references can be made to a destination domain name even if the IP address of the destination in the Internet changes. If a website chooses to locate a server at a new IP address, it does not have to change its domain name.

Rather, the name server for that domain name only has to respond with a new IP address when the name lookup occurs. Originally there were only 13 root servers on the Internet that pointed to the TLD name servers but since that time, using the Anycast routing system, hundreds of root servers populate the Internet today. In the beginning, domain names were expressed in Latin characters, letters A-Z, digits 0-9 and the hyphen. Upper and lower case was ignored for purposes of looking up domain names and translating them into IP addresses. As the Internet expansion continued, it was recognized that a broader range of scripts were needed to allow expression of domain names in Cyrillic, Greek, Chinese, Korean, Hebrew, Hindi, Urdu and many other languages. The IETF developed new standards for incorporating the Unicode character set into the DNS so that domain names could be expressed in many different scripts. Internationalized Domain Names (IDNs) could lead to some forms of fragmentation, depending on how uniformly the processing of domain names is done across the Internet.

Depending on the software used, there can be variations and failures to successfully look up domain names in the so-called IDN format. Efforts continue to implement this processing in a uniform fashion to minimize unintended fragmentation of the system. In its original formulation circa 1984, the DNS used a handful of generic toplevel domain names (gTLD): .com, .net, .org, .edu, .gov, .mil and .int. A special TLD included .arpa to assist in a transition from the original ARPANET naming scheme to the DNS.

Subsequently, two-letter codes created by the United Nations Statistics organization for countries and areas of economic interest were adopted as country code top-level domain names (ccTLD). There were on the order of 200 such codes, such as .us, .fr, .tk, .jp, .za, .ar (United States, France, Turkey, Japan, South Africa and Argentina, respectively). . 26 ICANN added additional gTLDs between 2000 and 2011, and in 2012 launched the new gTLD Programme. In the first round of the programme it received 1,930 applications, and as of December 2015, it had approved and delegated 853 of these into the root zone file. Another 480 applications are proceeding through the process, 560 have been withdrawn, and 37 have not been approved or are otherwise not proceeding.17 The expansion of the TLD space provides a broad range of choices for users to register second-level domain names such as abc.xyz and opens up many new opportunities for commerce, speech and community building. But it does raise an exceptionally wide range of issues that stakeholders and governments have laboured intensively to sort out, and among these involve new possibilities for fragmentation. A commonly heard criticism of the program that is sometimes framed in these terms has been that proliferation will lead to user uncertainty as to which domain names are authoritatively associated with which organizations or company brands.

It also raises questions about in which TLDs a corporation should register to avoid such confusion. To make matters more complex, trademarks can belong to more than one organization while domain names must be unique. Which Berlin is associated with .berlin? Is apple.com the same company as apple.coop? Users may end up at destinations that are not the ones they are expecting.

Together with the spread of IDNs, this may increase the likelihood that users will rely on search engines rather than names to find the resources they seek, as well as the importance of finding ways to validate destinations. Probably people may disagree as to whether all this counts as a sort of experiential fragmentation or simply confusion amidst complexity. More clearly a matter of fragmentation is that there is a possibility that the proliferation of new gTLDs will lead to increased blocking within the DNS. Already in 2011, many governments greeted ICANN’s approval of the .xxx gTLD for pornography with announcements that they would simply block the entire domain. As more character strings are entered into the root zone file that some governments deem to be risky, sensitive, or contrary to their laws, more national blocking could ensue.

Indeed, during the debates leading to the launch of the New gTLD Program, some governments and others argued for simply refusing approval to (some observers said censoring) certain strings on the grounds that widespread blocking was contrary to an open Internet and could even be technically destabilizing. The technical community generally has disagreed with the latter argument, although at least some eyebrows were raised in October 2015 by VeriSign’s quarterly filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission. The company noted that, “In view of our role as the Root Zone Maintainer, and as a root server operator, we face increased risks should ICANN’s delegation of these new gTLDs, which represent unprecedented changes to the root zone in volume and frequency, cause security and stability problems within the . 27 DNS and/or for parties who rely on the DNS. Such risks include potential instability of the DNS including potential fragmentation of the DNS should ICANN’s delegations create sufficient instability, and potential claims based on our role in the root zone provisioning and delegation process.”18 This legal prudence notwithstanding, it is unclear that instability will ensue, but there may be more gTLD blocking and hence more fragmentation in the DNS. Another concern relates to the interfaces and possible collisions between public and private names. The DNS design was intended to respond with the same information no matter where the lookup originated. This is an important uniformity principal that is worth preserving to achieve a level of uniformity in the behaviour of the global Internet.

This principal has already been altered by the use of internal corporate name servers that resolve to addresses, e.g. inside a corporate network and which are not reachable from outside a corporate boundary. This is sometimes referred to as split-horizon DNS and is useful for protecting access of corporate resources from outside the corporation network. There are also cases in which a lookup produces different results depending on the source IP address of the lookup.

For example, looking up Google.com may actually resolve to the IP address of Google.fr or Google.za depending on the source IP address of the DNS lookup. More generally, “What was a relatively uniform common public space is now being fenced into a number of realms, many of which are private.”19 There is another form of fragmentation that arises in the context paid access to Wi-Fe services in hotels, restaurants, etc. The user wishing to use the WiFi service typically tries to open a web page somewhere on the Internet.

The DNS lookup that follows is intercepted by the local router/resolver and a false response is returned that takes the user to a website that requests the user to log in or at least make a payment before access to the Internet will be permitted. For all practical purposes, the mechanics of this are like hijacking arbitrary domain names. One solution to this problem is the development of a protocol specific to the authorization and validation process for access to the local service rather than coercing the DNS lookup. Preservation of a common root zone and common TLD space across the Internet has been an important unifying principal.

Assuring that the information returned from a DNS lookup has been a high priority for protocol development and a method for achieving this uses digital signatures to bind the domain name to its associated IP address(es). The so-called domain name system security extensions (DNSSEC) standard is designed to allow the responses to domain name lookups to be checked for integrity and rejected if digital signatures do not match the expectations of the party doing the lookup. DNSSEC is already in use in the Internet and, in particular, the root zone with its references to all top-level domains is being signed for integrity. This could allow any domain name resolver to cache a copy of the root zone and be .

28 assured that the data has not been altered, and to reduce dependence on the existing system of Anycast root servers. We return below to DNSSEC and the use of cryptography. There is nothing in the Internet design that inhibits the creation of alternative ways to map identifiers into IP addresses. There have been experimental attempts to create alternate roots so as to allow users to choose different mappings of domain names to IP addresses or new identifiers spaces to be mapped into IP addresses. These generally have not succeeded, in part because they either required browser plug-ins to get to the right server or changes in the recursive resolvers to achieve the same objective.

Alternate domain name roots create a prima facie hazard since the same names may map to different IP addresses and thus different servers. Users may land on a server that is only pretending to be the legitimate destination. A variation of this hazard has arisen in a current project called YETI that plans to import the root zone of the DNS that is managed by ICANN, strip the digital signature from the zone and re-sign with a YETI key.20 While its proponents assert that it is not intended to provide an alternate root, it does, in effect, do exactly that. Once in place, it is possible for local resolvers to be configured to refer to the YETI name server rather than to the ICANN servers and all entries in the YETI root zone would appear to be valid if the YETI signing key is accepted.

Although its ostensible purpose is to explore limits to root server performance and functionality, it has to potential to introduce an alternate root. More generally, if ever leading governments or intergovernmental organizations were to implement an alternate root – a possibility that was sometimes raised in the highly charged geopolitical context of the WSIS negotiations – the results could be a game changer. Indeed, the establishment of an alternate root that has significant government backing arguably would be the mother of all fragmentations. There have been other identifier spaces developed that map into IP addresses such as the Digital Object Architecture developed by the Corporation for National Research Initiatives.21 Digital objects such as books, movies, music and other digitized content are assigned a unique and permanent identifier that can be looked up and mapped to an IP address where the object may be found. The importance of this work lies in the permanence of the identifier space.

In the DNS, if domain name registrations are not renews, the domain names may no longer resolve and references to digital objects (e.g. web pages) using these domain names may no longer resolve. . 29 Security For security and access control, it was thought in the original conception of the Internet that devices that wished to communicate only with known and authorized correspondents would make use of shared cryptographic keys as a means of validating legitimate correspondents. If the contents of received packets could be correctly decrypted, this was prima facie evidence that the sending party had legitimacy since the sharing of keys implied it. Of course, if a key has been obtained by stealth, bribery or cryptanalysis, this assumption would be incorrect. Although public key cryptography had been the subject of a spectacular 1976 IEEE article, at the time the early IPs were being defined in 1973-1978, this concept had not developed sufficiently for implementation to become part of the basic Internet security design.22 Since that time, public key cryptography has come into its own and is an important element for implementing confidentiality and authenticity in Internet-based exchanges. In fact, the notion of certificates and certificate authorities has evolved, using public key digital signatures, to allow correspondents to authenticate one another by confirming that a particular domain name, for example, is verifiably bound to a particular IP address or that a particular public key is verifiably associated with a particular domain name.

The World Wide Web hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP) added a security feature to become HTTPS. Its use invoked an exchange resulting in a shared symmetric key for cryptography and could also involve certificated validation by either party of the other’s identity. A certificate authority can issue a certificate that typically associates a public cryptographic key with an identifier (e.g. a domain name).

The certificate is signed with the private key of the certificate authority that matches the authority’s known public key. The recipient of the certificate can check the signature using the public key of the certificate authority. If it trusts the certificate authority and its signature, then it can use the public key in the certificate to authenticate the site associated with key. The IETF that develops technical standards for and implements the software and hardware mechanisms of the Internet develops various means to resist fragmentation.

To prevent alteration of the DNS mapping of domain name to IP address, which would results in serious fragmentation, they have developed DNSSECs. In this system, the association of the domain name and its IP addresses is digitally signed in the records of the DNS. A signed lookup can be requested to assure that the information has not been undetectably altered since the holder of the domain name put it in place.

DNSSEC reduces the risk of fragmentation by compromised domain name resolvers.23 With regard to routing, there also is a proposal that is not yet widely adopted and still needs technical refinement to protect the information distributed by the BGP from being corrupted by false announcements. . 30 Finally, the use of Certificate Authorities to authenticate the binding of domain names and public keys has been shown to be at risk either by penetration of a Certificate Authority by technical means leading to the production of false certificates or by corrupting a Certificate Authority to produce them. Assuming widespread use of DNSSEC in the DNS, a new proposal from the IETF called DANE would lodge public keys in the appropriate zone files of the DNS, limiting the ability for an abuser to produce corrupt certificates. In general, there is a trend towards the use of end-to-end cryptography to increase confidentiality and integrity of information exchanged through the Internet and the use of certificates and digital signatures to authenticate actors and the information they exchange. For example, a new proposal for protecting the privacy of domain name lookups is under consideration that would encrypt the domain name lookup itself. These practices are essential if widespread surveillance, deep packet inspection and other sources of privacy erosion are to be reduced. Conclusion In this section we have highlighted 12 kinds of technical fragmentation: 1.

Network Address Translation 2. IPv4 and IPv6 incompatibility and the dual-stack requirement 3. Routing corruption 4.

Firewall protections 5. Virtual private network isolation and blocking 6. TOR “onion space” and the “dark web” 7.

Internationalized Domain Name technical errors 8. Blocking of new gTLDs 9. Private name servers and the split-horizon DNS 10.

Segmented Wi-Fi services in hotels, restaurants, etc. 11. Possibility of significant alternate DNS roots 12. Certificate authorities producing false certificates .