Description

CFO Insights

Eyeing China—and its currency—

with caution

Changing dynamics in China’s currency policy and market

dynamics are adding to uncertainty in the direction of

the renminbi (RMB). Moreover, the recent turbulence in

China’s equity markets and the government-led creditexpansion effort there are topics CFOs of multinational

companies (MNCs) operating in China are watching

closely—and worrying about.

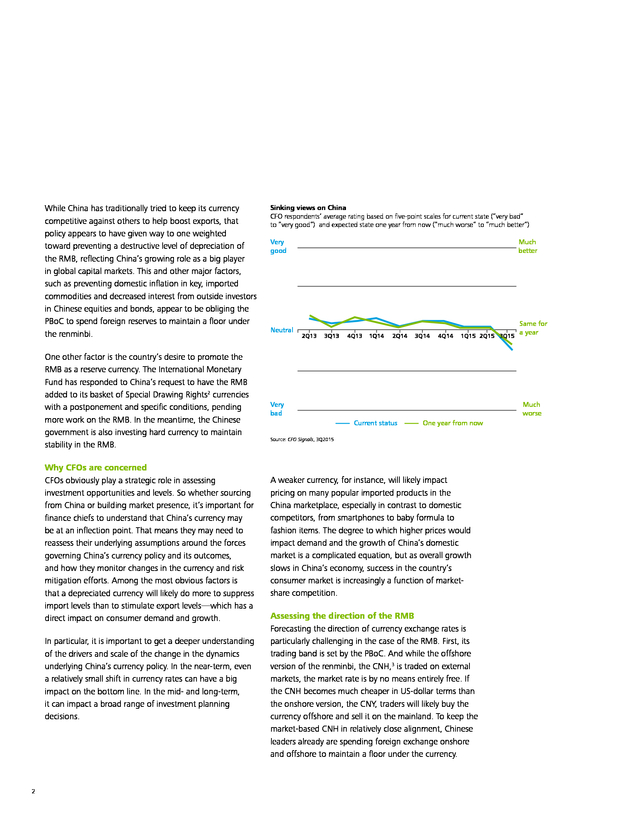

In the most recent CFO Signals™ survey, in fact, only

4% of finance chiefs viewed the Chinese economy as

good compared with 23% in Q2 (see chart: Sinking

views on China). And, on the one hand, much more

than in any other quarter, CFOs voiced strong concerns

about the impact on North America of slowing Chinese

growth—concerns that dampened their corporate growth

expectations in some cases.1

On the other hand, the domestic and global impact

of China’s slowdown may have outcomes, not entirely

negative, for both Chinese and non-Chinese MNCs, as

well as for emerging and industrialized economies. For

example, many of the “playing field” issues that have

challenged MNCs in Mainland China and in facing Chinese

competition for acquisitions and market share in third

countries may level off.

There is also the potential for new growth opportunities in Asia and beyond, as market forces lead China to settle into a more sustainable growth pattern, commodity prices stabilize, China’s massive enterprises are perforce put on a more commercially oriented reform path, and the Chinese currency evolves toward a more stable instrument for global trade and investment. Searching for stability In 2005, China announced the RMB would trade within a band against a basket of major currencies. Recently, however, as the US dollar (USD) has gained strength against other major currencies, most notably the euro, the RMB has risen with it, impacting China’s export competitiveness in Europe and some emerging markets, as well as the price of many goods imported into China. In response, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) devalued the currency in a surprise move in August, shaking world markets in the process, initially with a 1.6% move in the administrative trading band. But market pressures kicked in, and authorities have subsequently been trying to stabilize the currency at a rate of about 6.4 RMB to the dollar.

To do so, China spent $94 billion in reserves in August, and those levels are down about $400 billion from their peak a year ago. Moreover, estimates are that anywhere between RMB 2 trillion and RMB 4 trillion in new credit may be needed to stabilize the A-share market, increasing China’s already mammoth money supply. In this issue of CFO Insights, we’ll look at how the China currency crisis has evolved, as well as steps CFOs can take to monitor the RMB’s direction and to help mitigate the effect of a significant shift. 1 . While China has traditionally tried to keep its currency competitive against others to help boost exports, that policy appears to have given way to one weighted toward preventing a destructive level of depreciation of the RMB, reflecting China’s growing role as a big player in global capital markets. This and other major factors, such as preventing domestic inflation in key, imported commodities and decreased interest from outside investors in Chinese equities and bonds, appear to be obliging the PBoC to spend foreign reserves to maintain a floor under the renminbi. One other factor is the country’s desire to promote the RMB as a reserve currency. The International Monetary Fund has responded to China’s request to have the RMB added to its basket of Special Drawing Rights2 currencies with a postponement and specific conditions, pending more work on the RMB. In the meantime, the Chinese government is also investing hard currency to maintain stability in the RMB. Why CFOs are concerned CFOs obviously play a strategic role in assessing investment opportunities and levels.

So whether sourcing from China or building market presence, it’s important for finance chiefs to understand that China’s currency may be at an inflection point. That means they may need to reassess their underlying assumptions around the forces governing China’s currency policy and its outcomes, and how they monitor changes in the currency and risk mitigation efforts. Among the most obvious factors is that a depreciated currency will likely do more to suppress import levels than to stimulate export levels—which has a direct impact on consumer demand and growth. In particular, it is important to get a deeper understanding of the drivers and scale of the change in the dynamics underlying China’s currency policy.

In the near-term, even a relatively small shift in currency rates can have a big impact on the bottom line. In the mid- and long-term, it can impact a broad range of investment planning decisions. 2 Sinking views on China CFO respondents’ average rating based on five-point scales for current state (“very bad” to “very good”) and expected state one year from now (“much worse” to “much better”) Very good Neutral Much better 2Q13 3Q13 4Q13 1Q14 2Q14 3Q14 4Q14 1Q15 2Q15 3Q15 Very bad Same for a year Much worse Current status One year from now Source: CFO Signals, 3Q2015 A weaker currency, for instance, will likely impact pricing on many popular imported products in the China marketplace, especially in contrast to domestic competitors, from smartphones to baby formula to fashion items. The degree to which higher prices would impact demand and the growth of China’s domestic market is a complicated equation, but as overall growth slows in China’s economy, success in the country’s consumer market is increasingly a function of marketshare competition. Assessing the direction of the RMB Forecasting the direction of currency exchange rates is particularly challenging in the case of the RMB.

First, its trading band is set by the PBoC. And while the offshore version of the renminbi, the CNH,3 is traded on external markets, the market rate is by no means entirely free. If the CNH becomes much cheaper in US-dollar terms than the onshore version, the CNY, traders will likely buy the currency offshore and sell it on the mainland.

To keep the market-based CNH in relatively close alignment, Chinese leaders already are spending foreign exchange onshore and offshore to maintain a floor under the currency. . Some of the factors influencing authorities in China that oversee the exchange value of the currency, include the following: • The RMB has become an expensive currency compared with the euro, making it very difficult to maintain any level of exports to Europe; • Other countries in Southeast Asia and Latin America are much more competitive now on a currency basis; • Since the onset of volatility in the A-share market, analysts have noted China’s shrinking position in US Treasuries, a steady monthly decline in foreign-exchange reserves, and a high level of capital leaving China; • The PBoC may have less than US$1 trillion of immediate liquidity to support the A-share market and the currency even though China’s foreign-exchange reserves are still huge—in the US$3.5 trillion range.4 But China has a difficult balancing act in terms of how much it is willing to spend to keep the RMB strong. Such an action in and of itself could weaken global sentiment on the RMB and the government-supported institutions that are players in the intervention. For example, China’s large state-owned enterprise brokerages, which have just increased their pledges to buy and support A-shares, are seeing their own share values hammered. Still, it’s important that MNCs understand the general direction of the currency over the next 12 to 18 months. There are various indicators that, if monitored together, can be viewed as a planning tool. One is the actual currency-trading levels in both Hong Kong and Mainland China.

Take the level of RMB versus Hong Kong dollars (HKD) held in retail bank accounts in Hong Kong. If you live in Hong Kong, you can choose to keep money in your bank account in RMB or in HKD, which is a USD surrogate. Other important indicators are the relative level of RMB trade settlement versus USD trade settlement, forward pricing of the RMB on various futures markets, the arbitrage difference between the CNH and CNY, and the reported changes in China’s US Treasury holdings and foreign-exchange levels. Mitigating currency risks Given this fluid and changing environment, now may be a good time to perform a thorough review of how currency is managed at your company.

Specifically: • Companies with substantial renminbi holdings might think through how they can offset the risk of significant currency-rate swings with investment mechanisms or lending mechanisms and related hedging strategies. For example, in some cases, trading regulations allow companies to take a short position in RMB against a long position in other currencies outside China. Other steps, such as currency hedging with instruments like currency forwards, have become more expensive, so CFOs have to balance the value of those strategies against the rising cost. • Where RMB can be converted to other currencies, it may be prudent to reduce exposure. Companies might also revisit how they can hedge by looking at how they conduct their business.

For example, CFOs can look at how they can align more of their costs to be domestic costs, in what currencies their cross-border transactions are contracted, and how they can do financing within the marketplace in which they are operating. • In terms of contracts and cross-border trading, some MNCs are more protected against currency changes than others. For example, some elements of a contract might be denominated in RMB and some in USD. Sometimes a transaction might be settled on China’s mainland or settled offshore with a trading company that has the rights to take it into the mainland and do the transaction. At present, Chinese bankers have noted that the appetite for exchange requests from RMB into USD is at a multi-year high.

That provides additional leverage for those who have US dollars to spend in transaction settlements. 3 . • CFOs may want to review the terms and conditions of contracts and cross-border agreements so that they can be prepared for any potential exposure to shifts in the renminbi. The history of gradual exchange-rate shifts in the range of 2% to 6%, which were typical of the l, Global Research Director, CFO Program, Deloitte LLP; P RMB from 2005 until a few months ago, were more easily managed. But the recent rate of change can have significant bottom-line impact given the large size of the businesses many MNCs have built in China. A useful first step may be to model the financial impact of shifts of this size or larger in a much more compressed time frame. Even with slowing growth, China’s domestic market is still growing faster relative to other large markets, which, along with its sheer size, is a big reason companies are willing to take on the challenges and the learning curve required to succeed in that marketplace.

Still, recent shifts in the RMB are important indicators of the potential size of changes that may lie ahead. It is important for CFOs to consider taking stock of their RMB currency holdings, monitoring their currency risks in China on an ongoing basis, and exploring ways to decrease or deploy RMB assets they may be holding in the Chinese mainland. Contacts Ken DeWoskin Independent Senior Advisor, Chinese Services Group Deloitte LLP kedewoskin@deloitte.com George Warnock Partner; Americas Leader, Chinese Services Group Deloitte Services LP gwarnock@deloitte.com Deloitte CFO Insights are developed with the guidance of Dr. Ajit Kambil, Global Research Director, CFO Program, Deloitte LLP; and Lori Calabro, Senior Manager, CFO Education & Events, Deloitte LLP. About Deloitte’s CFO Program The CFO Program brings together a multidisciplinary team of Deloitte leaders and subject matter specialists to help CFOs stay ahead in the face of growing challenges and demands.

The Program harnesses our organization’s broad capabilities to deliver forward thinking and fresh insights for every stage of a CFO’s career – helping CFOs manage the aders and subject matter specialists to help CFOs stay ahead in the face of growing challenges and demands. The Program harnessestheir roles, tackle their company’s complexities of our Endnotes sights for every stage of a CFO’s career – helping CFOs manage the complexities of their roles, tackle their company’s most compelling most compelling challenges, and adapt to strategic 1 CFO Signals, 3Q2015, US CFO Program, Deloitte LLP. 2 shifts in the market. The Special Drawing Rights is an international reserve asset, created by the t: International Monetary Fund in 1969 to supplement its member countries’ official reserves. Its value is based on a basket of four key international currencies, and SDRs can be exchanged for freely usable currencies.

International Monetary Fund, For more information about Deloitte’s CFO Program, visit SDR Fact Sheet: http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/sdr.htm. y means of this publication, rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice or services. This 3 CNH basis “offshore” version action that may affect Mainland China, mostly or should it be used as a is the for any decision or of RMB, traded outsideyour business. Before making any decision or takingat: www.deloitte.com/us/thecfoprogram. our website any action that may in responsible CNY is the sustained version of China’s relies on this publication. Deloitte shall not be Hong Kong.for any loss “onshore” by any person whocurrency, traded within Mainland China.

The CNH is also used as a quasi-legal tender in Hong Kong and in some S.E. Asian and Central Asian centers. http://www.wsj.com/articles/china-august-forex-reserves-down-by-93-9-billionas-pboc-intervenes-1441614856. 4 Follow us @deloittecfo This publication contains general information only and is based on the experiences and research of Deloitte practitioners. Deloitte is not, by means of this publication, rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice or services. This publication is not a substitute for such professional advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business.

Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified professional advisor. Deloitte shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person who relies on this publication. About Deloitte Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, a UK private company limited by guarantee (“DTTL”), its network of member firms, and their related entities. DTTL and each of its member firms are legally separate and independent entities.

DTTL (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) does not provide services to clients. Please see www.deloitte.com/about for a detailed description of DTTL and its member firms. Please see www.deloitte.com/us/about for a detailed description of the legal structure of Deloitte LLP and its subsidiaries.

Certain services may not be available to attest clients under the rules and regulations of public accounting. Copyright© 2015 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved. Member of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited. 4 .

There is also the potential for new growth opportunities in Asia and beyond, as market forces lead China to settle into a more sustainable growth pattern, commodity prices stabilize, China’s massive enterprises are perforce put on a more commercially oriented reform path, and the Chinese currency evolves toward a more stable instrument for global trade and investment. Searching for stability In 2005, China announced the RMB would trade within a band against a basket of major currencies. Recently, however, as the US dollar (USD) has gained strength against other major currencies, most notably the euro, the RMB has risen with it, impacting China’s export competitiveness in Europe and some emerging markets, as well as the price of many goods imported into China. In response, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) devalued the currency in a surprise move in August, shaking world markets in the process, initially with a 1.6% move in the administrative trading band. But market pressures kicked in, and authorities have subsequently been trying to stabilize the currency at a rate of about 6.4 RMB to the dollar.

To do so, China spent $94 billion in reserves in August, and those levels are down about $400 billion from their peak a year ago. Moreover, estimates are that anywhere between RMB 2 trillion and RMB 4 trillion in new credit may be needed to stabilize the A-share market, increasing China’s already mammoth money supply. In this issue of CFO Insights, we’ll look at how the China currency crisis has evolved, as well as steps CFOs can take to monitor the RMB’s direction and to help mitigate the effect of a significant shift. 1 . While China has traditionally tried to keep its currency competitive against others to help boost exports, that policy appears to have given way to one weighted toward preventing a destructive level of depreciation of the RMB, reflecting China’s growing role as a big player in global capital markets. This and other major factors, such as preventing domestic inflation in key, imported commodities and decreased interest from outside investors in Chinese equities and bonds, appear to be obliging the PBoC to spend foreign reserves to maintain a floor under the renminbi. One other factor is the country’s desire to promote the RMB as a reserve currency. The International Monetary Fund has responded to China’s request to have the RMB added to its basket of Special Drawing Rights2 currencies with a postponement and specific conditions, pending more work on the RMB. In the meantime, the Chinese government is also investing hard currency to maintain stability in the RMB. Why CFOs are concerned CFOs obviously play a strategic role in assessing investment opportunities and levels.

So whether sourcing from China or building market presence, it’s important for finance chiefs to understand that China’s currency may be at an inflection point. That means they may need to reassess their underlying assumptions around the forces governing China’s currency policy and its outcomes, and how they monitor changes in the currency and risk mitigation efforts. Among the most obvious factors is that a depreciated currency will likely do more to suppress import levels than to stimulate export levels—which has a direct impact on consumer demand and growth. In particular, it is important to get a deeper understanding of the drivers and scale of the change in the dynamics underlying China’s currency policy.

In the near-term, even a relatively small shift in currency rates can have a big impact on the bottom line. In the mid- and long-term, it can impact a broad range of investment planning decisions. 2 Sinking views on China CFO respondents’ average rating based on five-point scales for current state (“very bad” to “very good”) and expected state one year from now (“much worse” to “much better”) Very good Neutral Much better 2Q13 3Q13 4Q13 1Q14 2Q14 3Q14 4Q14 1Q15 2Q15 3Q15 Very bad Same for a year Much worse Current status One year from now Source: CFO Signals, 3Q2015 A weaker currency, for instance, will likely impact pricing on many popular imported products in the China marketplace, especially in contrast to domestic competitors, from smartphones to baby formula to fashion items. The degree to which higher prices would impact demand and the growth of China’s domestic market is a complicated equation, but as overall growth slows in China’s economy, success in the country’s consumer market is increasingly a function of marketshare competition. Assessing the direction of the RMB Forecasting the direction of currency exchange rates is particularly challenging in the case of the RMB.

First, its trading band is set by the PBoC. And while the offshore version of the renminbi, the CNH,3 is traded on external markets, the market rate is by no means entirely free. If the CNH becomes much cheaper in US-dollar terms than the onshore version, the CNY, traders will likely buy the currency offshore and sell it on the mainland.

To keep the market-based CNH in relatively close alignment, Chinese leaders already are spending foreign exchange onshore and offshore to maintain a floor under the currency. . Some of the factors influencing authorities in China that oversee the exchange value of the currency, include the following: • The RMB has become an expensive currency compared with the euro, making it very difficult to maintain any level of exports to Europe; • Other countries in Southeast Asia and Latin America are much more competitive now on a currency basis; • Since the onset of volatility in the A-share market, analysts have noted China’s shrinking position in US Treasuries, a steady monthly decline in foreign-exchange reserves, and a high level of capital leaving China; • The PBoC may have less than US$1 trillion of immediate liquidity to support the A-share market and the currency even though China’s foreign-exchange reserves are still huge—in the US$3.5 trillion range.4 But China has a difficult balancing act in terms of how much it is willing to spend to keep the RMB strong. Such an action in and of itself could weaken global sentiment on the RMB and the government-supported institutions that are players in the intervention. For example, China’s large state-owned enterprise brokerages, which have just increased their pledges to buy and support A-shares, are seeing their own share values hammered. Still, it’s important that MNCs understand the general direction of the currency over the next 12 to 18 months. There are various indicators that, if monitored together, can be viewed as a planning tool. One is the actual currency-trading levels in both Hong Kong and Mainland China.

Take the level of RMB versus Hong Kong dollars (HKD) held in retail bank accounts in Hong Kong. If you live in Hong Kong, you can choose to keep money in your bank account in RMB or in HKD, which is a USD surrogate. Other important indicators are the relative level of RMB trade settlement versus USD trade settlement, forward pricing of the RMB on various futures markets, the arbitrage difference between the CNH and CNY, and the reported changes in China’s US Treasury holdings and foreign-exchange levels. Mitigating currency risks Given this fluid and changing environment, now may be a good time to perform a thorough review of how currency is managed at your company.

Specifically: • Companies with substantial renminbi holdings might think through how they can offset the risk of significant currency-rate swings with investment mechanisms or lending mechanisms and related hedging strategies. For example, in some cases, trading regulations allow companies to take a short position in RMB against a long position in other currencies outside China. Other steps, such as currency hedging with instruments like currency forwards, have become more expensive, so CFOs have to balance the value of those strategies against the rising cost. • Where RMB can be converted to other currencies, it may be prudent to reduce exposure. Companies might also revisit how they can hedge by looking at how they conduct their business.

For example, CFOs can look at how they can align more of their costs to be domestic costs, in what currencies their cross-border transactions are contracted, and how they can do financing within the marketplace in which they are operating. • In terms of contracts and cross-border trading, some MNCs are more protected against currency changes than others. For example, some elements of a contract might be denominated in RMB and some in USD. Sometimes a transaction might be settled on China’s mainland or settled offshore with a trading company that has the rights to take it into the mainland and do the transaction. At present, Chinese bankers have noted that the appetite for exchange requests from RMB into USD is at a multi-year high.

That provides additional leverage for those who have US dollars to spend in transaction settlements. 3 . • CFOs may want to review the terms and conditions of contracts and cross-border agreements so that they can be prepared for any potential exposure to shifts in the renminbi. The history of gradual exchange-rate shifts in the range of 2% to 6%, which were typical of the l, Global Research Director, CFO Program, Deloitte LLP; P RMB from 2005 until a few months ago, were more easily managed. But the recent rate of change can have significant bottom-line impact given the large size of the businesses many MNCs have built in China. A useful first step may be to model the financial impact of shifts of this size or larger in a much more compressed time frame. Even with slowing growth, China’s domestic market is still growing faster relative to other large markets, which, along with its sheer size, is a big reason companies are willing to take on the challenges and the learning curve required to succeed in that marketplace.

Still, recent shifts in the RMB are important indicators of the potential size of changes that may lie ahead. It is important for CFOs to consider taking stock of their RMB currency holdings, monitoring their currency risks in China on an ongoing basis, and exploring ways to decrease or deploy RMB assets they may be holding in the Chinese mainland. Contacts Ken DeWoskin Independent Senior Advisor, Chinese Services Group Deloitte LLP kedewoskin@deloitte.com George Warnock Partner; Americas Leader, Chinese Services Group Deloitte Services LP gwarnock@deloitte.com Deloitte CFO Insights are developed with the guidance of Dr. Ajit Kambil, Global Research Director, CFO Program, Deloitte LLP; and Lori Calabro, Senior Manager, CFO Education & Events, Deloitte LLP. About Deloitte’s CFO Program The CFO Program brings together a multidisciplinary team of Deloitte leaders and subject matter specialists to help CFOs stay ahead in the face of growing challenges and demands.

The Program harnesses our organization’s broad capabilities to deliver forward thinking and fresh insights for every stage of a CFO’s career – helping CFOs manage the aders and subject matter specialists to help CFOs stay ahead in the face of growing challenges and demands. The Program harnessestheir roles, tackle their company’s complexities of our Endnotes sights for every stage of a CFO’s career – helping CFOs manage the complexities of their roles, tackle their company’s most compelling most compelling challenges, and adapt to strategic 1 CFO Signals, 3Q2015, US CFO Program, Deloitte LLP. 2 shifts in the market. The Special Drawing Rights is an international reserve asset, created by the t: International Monetary Fund in 1969 to supplement its member countries’ official reserves. Its value is based on a basket of four key international currencies, and SDRs can be exchanged for freely usable currencies.

International Monetary Fund, For more information about Deloitte’s CFO Program, visit SDR Fact Sheet: http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/sdr.htm. y means of this publication, rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice or services. This 3 CNH basis “offshore” version action that may affect Mainland China, mostly or should it be used as a is the for any decision or of RMB, traded outsideyour business. Before making any decision or takingat: www.deloitte.com/us/thecfoprogram. our website any action that may in responsible CNY is the sustained version of China’s relies on this publication. Deloitte shall not be Hong Kong.for any loss “onshore” by any person whocurrency, traded within Mainland China.

The CNH is also used as a quasi-legal tender in Hong Kong and in some S.E. Asian and Central Asian centers. http://www.wsj.com/articles/china-august-forex-reserves-down-by-93-9-billionas-pboc-intervenes-1441614856. 4 Follow us @deloittecfo This publication contains general information only and is based on the experiences and research of Deloitte practitioners. Deloitte is not, by means of this publication, rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice or services. This publication is not a substitute for such professional advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business.

Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified professional advisor. Deloitte shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person who relies on this publication. About Deloitte Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, a UK private company limited by guarantee (“DTTL”), its network of member firms, and their related entities. DTTL and each of its member firms are legally separate and independent entities.

DTTL (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) does not provide services to clients. Please see www.deloitte.com/about for a detailed description of DTTL and its member firms. Please see www.deloitte.com/us/about for a detailed description of the legal structure of Deloitte LLP and its subsidiaries.

Certain services may not be available to attest clients under the rules and regulations of public accounting. Copyright© 2015 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved. Member of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited. 4 .