North America Renewable Energy Brief: Can Community Solar Bring Renewable Energy to the Masses? - March 29, 2016

CohnReznick

Description

Page 1

North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016

NORTH AMERICA

R E N E WA B L E E N E R G Y B R I E F

CAN COMMUNITY SOLAR BRING RENEWABLE

ENERGY TO THE MASSES? – MARCH 2016

. Page 2

North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016

IN FOCUS: CAN COMMUNITY SOLAR BRING RENEWABLE ENERGY TO THE MASSES?

The huge market potential

Financing challenges and considerations

The utility viewpoint

The interplay with rooftop solar

Welcome to the fourth edition of North America Renewable Energy Brief. This issue of

the publication is focused on the emerging community energy sector. We examine

the market potential for community solar, which states will likely see the most projects,

how community solar projects might be financed, whether utilities view this market

as an opportunity or a threat, and whether community energy competes with, or is

complementary to, rooftop solar.

We hope you find this newsletter thought provoking and insightful. As always, we

welcome your feedback.

Sincerely,

Anton Cohen and Tim Kemper

Rob Sternthal

Co-National Directors, Renewable Energy Industry

CohnReznick LLP

President

CohnReznick Capital Markets Securities LLC

WHAT IS COMMUNITY SOLAR?

Community solar is a relatively new phenomenon

so a definition is a good place to start.

Also referred to as shared renewables, community renewables, or even solar ‘gardens’, community solar is an energy procurement model that allows private companies, institutions and individuals to aggregate their electricity load to purchase clean energy on behalf of those who wish to participate. The model offers an alternative to rooftop solar for both individuals and businesses wishing to benefit from the stable pricing and green credentials that renewable energy affords but can’t because their rooftops are not suitable for solar panels or they are renters. Community solar works in partnership with local utilities, which continue to deliver power, maintain the grid, and may provide consolidated billing and other customer services. However, the customers pay a community solar project instead of the utilities and receive credits on their electricity bills for the power procured. Community solar projects can be developed and owned by utilities or other third parties. Customers can either pay upfront for a portion of the project’s output or for a portion of a project’s capacity. Further, customers can either pay an entire amount up front or pay periodically, such as monthly. .

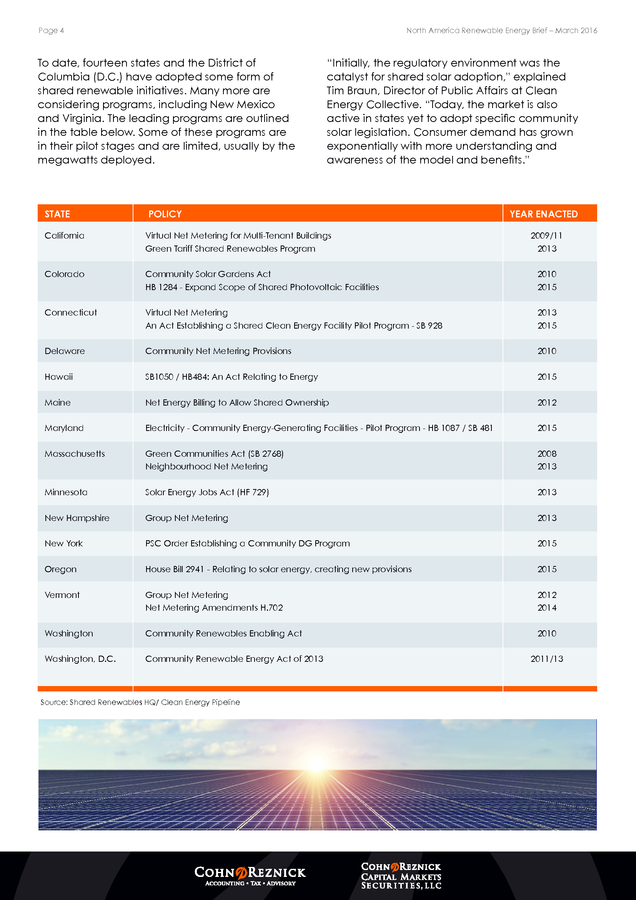

Page 3 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 ENABLING LEGISLATION CREATES HUGE GROWTH POTENTIAL The market potential for community solar is huge. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates community solar could represent 32%-49% of the distributed PV market by 2020. This equates to cumulative 5.5-11.0 GW of capacity projected to be brought online between 2015 and 2020, or between $8.2 billion and $16.3 billion of cumulative investment1. As shown in the graph below, it is unlikely that more than 1 GW of community solar projects will be brought online this year or next. But in 2020, potentially, more than 4GW of community solar projects could be installed. 1 David Feldman, Anna M.

Brockway, Elaine Ulrich, and Robert Margolis, Shared Solar: Current Landscape, Market Potential, and the Impact of Federal Securities Regulation, (April 2015), www.nrel.gov/docs/fy15osti/63892.pdf p.v Estimated market potential of onsite and shared solar distributed PV capacity 10 Annual US PV Demand (GW) 9 8 7 6 5 Shared Solar GW (Historic) 4 Shared Solar GW (High) 3 Shared Solar GW (Low) 2 Distributed PV Market 1 0 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Source: National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) The rapid rate of community solar development that followed the implementation of enabling legislation highlights its potential. Take the state of Minnesota as an example. Minnesota passed the Solar Energy Jobs Act in 2013, a key piece of enabling legislation that made community solar commercially viable.

At the time, only 14 MW of community solar had been installed state-wide. As Karen Gados, Business Development Manager at SunShare explains, development activity skyrocketed following the legislation. “Within the first week of the community solar program opening, the state received over 400 applications for approximately 458 MW of capacity,” she said. “To date, they have received 2 GW.” What is driving community solar growth? Without doubt, the most important factor is the establishment of enabling legislation that allows projects to sell power to multiple offtakers - residents, municipalities, or businesses (so-called third-party PPAs). The legislation may also allow customers of community solar projects to receive monetary or electricity credits to offset their electricity bills.

The type of legislation that enables crediting depends on the dynamics of the market. It could include a specific community solar program or virtual net metering. Also, these offsets may be at wholesale or retail rates, or somewhere in between. .

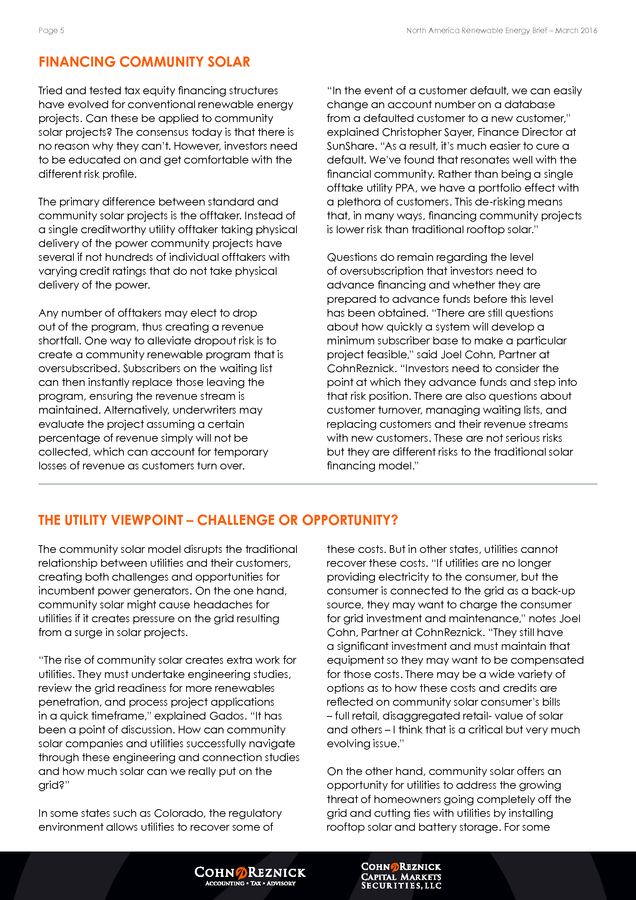

Page 4 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 To date, fourteen states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) have adopted some form of shared renewable initiatives. Many more are considering programs, including New Mexico and Virginia. The leading programs are outlined in the table below. Some of these programs are in their pilot stages and are limited, usually by the megawatts deployed. STATE “Initially, the regulatory environment was the catalyst for shared solar adoption,” explained Tim Braun, Director of Public Affairs at Clean Energy Collective.

“Today, the market is also active in states yet to adopt specific community solar legislation. Consumer demand has grown exponentially with more understanding and awareness of the model and benefits.” POLICY YEAR ENACTED California Virtual Net Metering for Multi-Tenant Buildings Green Tariff Shared Renewables Program Colorado Community Solar Gardens Act HB 1284 - Expand Scope of Shared Photovoltaic Facilities 2010 2015 Connecticut Virtual Net Metering An Act Establishing a Shared Clean Energy Facility Pilot Program - SB 928 2013 2015 Delaware Community Net Metering Provisions 2010 Hawaii SB1050 / HB484: An Act Relating to Energy 2015 Maine Net Energy Billing to Allow Shared Ownership 2012 Maryland Electricity - Community Energy-Generating Facilities - Pilot Program - HB 1087 / SB 481 2015 Massachusetts Green Communities Act (SB 2768) Neighbourhood Net Metering 2008 2013 Minnesota Solar Energy Jobs Act (HF 729) 2013 New Hampshire Group Net Metering 2013 New York PSC Order Establishing a Community DG Program 2015 Oregon House Bill 2941 - Relating to solar energy, creating new provisions 2015 Vermont Group Net Metering Net Metering Amendments H.702 2012 2014 Washington Community Renewables Enabling Act 2010 Washington, D.C. Community Renewable Energy Act of 2013 Source: Shared Renewables HQ/ Clean Energy Pipeline 2009/11 2013 2011/13 . Page 5 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 FINANCING COMMUNITY SOLAR Tried and tested tax equity financing structures have evolved for conventional renewable energy projects. Can these be applied to community solar projects? The consensus today is that there is no reason why they can’t. However, investors need to be educated on and get comfortable with the different risk profile. The primary difference between standard and community solar projects is the offtaker. Instead of a single creditworthy utility offtaker taking physical delivery of the power community projects have several if not hundreds of individual offtakers with varying credit ratings that do not take physical delivery of the power. Any number of offtakers may elect to drop out of the program, thus creating a revenue shortfall.

One way to alleviate dropout risk is to create a community renewable program that is oversubscribed. Subscribers on the waiting list can then instantly replace those leaving the program, ensuring the revenue stream is maintained. Alternatively, underwriters may evaluate the project assuming a certain percentage of revenue simply will not be collected, which can account for temporary losses of revenue as customers turn over. “In the event of a customer default, we can easily change an account number on a database from a defaulted customer to a new customer,” explained Christopher Sayer, Finance Director at SunShare.

“As a result, it’s much easier to cure a default. We’ve found that resonates well with the financial community. Rather than being a single offtake utility PPA, we have a portfolio effect with a plethora of customers.

This de-risking means that, in many ways, financing community projects is lower risk than traditional rooftop solar.” Questions do remain regarding the level of oversubscription that investors need to advance financing and whether they are prepared to advance funds before this level has been obtained. “There are still questions about how quickly a system will develop a minimum subscriber base to make a particular project feasible,” said Joel Cohn, Partner at CohnReznick. “Investors need to consider the point at which they advance funds and step into that risk position.

There are also questions about customer turnover, managing waiting lists, and replacing customers and their revenue streams with new customers. These are not serious risks but they are different risks to the traditional solar financing model.” THE UTILITY VIEWPOINT – CHALLENGE OR OPPORTUNITY? The community solar model disrupts the traditional relationship between utilities and their customers, creating both challenges and opportunities for incumbent power generators. On the one hand, community solar might cause headaches for utilities if it creates pressure on the grid resulting from a surge in solar projects. “The rise of community solar creates extra work for utilities.

They must undertake engineering studies, review the grid readiness for more renewables penetration, and process project applications in a quick timeframe,” explained Gados. “It has been a point of discussion. How can community solar companies and utilities successfully navigate through these engineering and connection studies and how much solar can we really put on the grid?” In some states such as Colorado, the regulatory environment allows utilities to recover some of these costs.

But in other states, utilities cannot recover these costs. “If utilities are no longer providing electricity to the consumer, but the consumer is connected to the grid as a back-up source, they may want to charge the consumer for grid investment and maintenance,” notes Joel Cohn, Partner at CohnReznick. “They still have a significant investment and must maintain that equipment so they may want to be compensated for those costs.

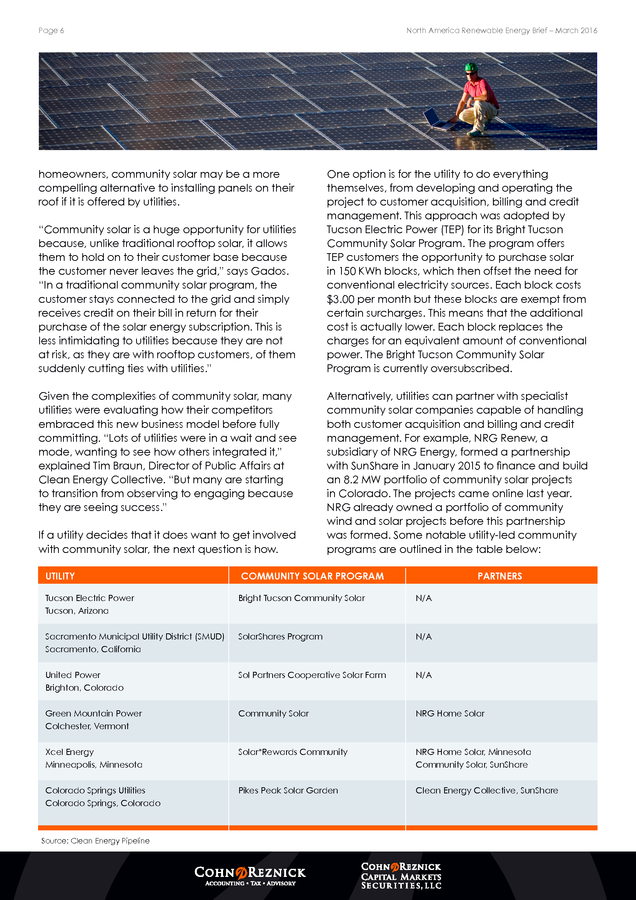

There may be a wide variety of options as to how these costs and credits are reflected on community solar consumer’s bills – full retail, disaggregated retail- value of solar and others – I think that is a critical but very much evolving issue.” On the other hand, community solar offers an opportunity for utilities to address the growing threat of homeowners going completely off the grid and cutting ties with utilities by installing rooftop solar and battery storage. For some . Page 6 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 homeowners, community solar may be a more compelling alternative to installing panels on their roof if it is offered by utilities. “Community solar is a huge opportunity for utilities because, unlike traditional rooftop solar, it allows them to hold on to their customer base because the customer never leaves the grid,” says Gados. “In a traditional community solar program, the customer stays connected to the grid and simply receives credit on their bill in return for their purchase of the solar energy subscription. This is less intimidating to utilities because they are not at risk, as they are with rooftop customers, of them suddenly cutting ties with utilities.” Given the complexities of community solar, many utilities were evaluating how their competitors embraced this new business model before fully committing. “Lots of utilities were in a wait and see mode, wanting to see how others integrated it,” explained Tim Braun, Director of Public Affairs at Clean Energy Collective. “But many are starting to transition from observing to engaging because they are seeing success.” If a utility decides that it does want to get involved with community solar, the next question is how. UTILITY One option is for the utility to do everything themselves, from developing and operating the project to customer acquisition, billing and credit management.

This approach was adopted by Tucson Electric Power (TEP) for its Bright Tucson Community Solar Program. The program offers TEP customers the opportunity to purchase solar in 150 KWh blocks, which then offset the need for conventional electricity sources. Each block costs $3.00 per month but these blocks are exempt from certain surcharges.

This means that the additional cost is actually lower. Each block replaces the charges for an equivalent amount of conventional power. The Bright Tucson Community Solar Program is currently oversubscribed. Alternatively, utilities can partner with specialist community solar companies capable of handling both customer acquisition and billing and credit management.

For example, NRG Renew, a subsidiary of NRG Energy, formed a partnership with SunShare in January 2015 to finance and build an 8.2 MW portfolio of community solar projects in Colorado. The projects came online last year. NRG already owned a portfolio of community wind and solar projects before this partnership was formed. Some notable utility-led community programs are outlined in the table below: COMMUNITY SOLAR PROGRAM PARTNERS Tucson Electric Power Tucson, Arizona Bright Tucson Community Solar N/A Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) Sacramento, California SolarShares Program N/A United Power Brighton, Colorado Sol Partners Cooperative Solar Farm N/A Green Mountain Power Colchester, Vermont Community Solar NRG Home Solar Xcel Energy Minneapolis, Minnesota Solar*Rewards Community NRG Home Solar, Minnesota Community Solar, SunShare Colorado Springs Utilities Colorado Springs, Colorado Pikes Peak Solar Garden Clean Energy Collective, SunShare Source: Clean Energy Pipeline .

Page 7 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 “Community solar is beginning to flourish. Financing partners are getting comfortable with it and it’s attractive because it de-risks the biggest issue with residential solar: non-payment. Most community solar projects are oversubscribed so someone else can step in and pay if this problem occurs. The more forward thinking utilities understand that community solar is their opportunity to work with their customer base in a proactive and efficient way.” Conor McKenna, Managing Director, CohnReznick Capital Markets Securities, LLC ROOFTOP SOLAR – FRIEND OR FOE? The US rooftop solar market is booming. The Solar Energy Industries Association estimates that, for the first time ever, more than 2 GW of residential solar was installed in 2015, significantly more than in 2014.

If rooftop and community solar are in competition, this growth might stunt the rise of community solar before it has taken off. On the flip side, a surge in community solar might slow the growth of rooftop solar. The industry professionals interviewed for this report believe that community and rooftop solar are often not in direct competition. This is primarily because rooftop solar is not logistically possible for such a large number of households. In fact, The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates that 49% of households in the US are currently unable to host a PV system (after excluding those that do not own their building and those without access to sufficient roof space.)2 Therefore, half of all households in the US do not have the choice of whether to install solar on their roof or sign up for a community solar program, but instead are limited to a choice between community solar and no solar at all. Even for households that can accommodate rooftop solar, community solar could be a more 2 appealing option because it is more flexible. “With rooftop solar, you have an agreement that offers financial savings but it’s also a rigid commitment,” said Sandy Roskes, Senior Vice President of New Ventures at Ethical Electric.

“You either need to buy the asset and hold it long-term or you need to enter into a long-term financial arrangement. In addition to community solar being an option for households that cannot accommodate rooftop solar, it also enables individuals to decide how much capital they want to commit, and for how long, in a way that rooftop can’t.” Some community solar companies consider the market opportunity to be so extensive that they do not target households with rooftops suitable for solar. “The 2015 NREL report on shared solar stated around half of people can’t participate in rooftop solar.

But we think it’s safe to say that anywhere between 50-80% of people can’t accommodate rooftop solar,” explained Gados. “Those are the folks that we are targeting. If we get a phone call from someone asking for solar on their rooftop we will usually refer them to someone at the local solar association.

We don’t view the rooftop industry as competition in any shape or form.” David Feldman, Anna M. Brockway, Elaine Ulrich, and Robert Margolis, Shared Solar: Current Landscape, Market Potential, and the Impact of Federal Securities Regulation, (April 2015), www.nrel.gov/docs/fy15osti/63892.pdf p.v . Page 8 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 WHAT DOES COHNREZNICK THINK? The community solar model is gathering momentum. The projections made by the NREL and the Department of Energy that were mentioned earlier make this abundantly clear. The question is, therefore, not whether this market will grow but by how much. And what will the impact be on incumbent players - notably the utilities and rooftop solar companies. The examples highlighted earlier demonstrate that forward thinking utilities can benefit hugely from engaging with community solar. Of course, careful consideration needs to be given to how projects are structured and the extent to which key aspects of the projects, such as customer acquisition and management, are outsourced to partners.

But if structured correctly, community solar should enable utilities to retain a healthy relationship with their customers. There is also the question of financing. Our view is that, ultimately, the structures that have been used for many years can be applied to community projects. Of course the risk profile is different. For a start, community projects rely on multiple virtual offtakers that, at any point, may choose to exit the program.

This risk could be minimized depending upon how the program is structured. But the unique features of community solar are also, in many ways, less risky to investors. Projects can manage waiting lists of customers, with any defaults being rectified fairly easily. As always, we recommend seeking professional advice to help navigate through these issues and welcome all conversation in response to this paper. About CohnReznick: CohnReznick LLP is one of the top accounting, tax, and advisory firms in the United States, combining the resources and technical expertise of a national firm with the hands-on, entrepreneurial approach that today’s dynamic business environment demands.

Headquartered in New York, NY, and with offices nationwide, CohnReznick serves a large number of diverse industries and offers specialized services for middle market and Fortune 1000 companies, private equity and financial services firms, government contractors, government agencies, and not-for-profit organizations. The Firm, with origins dating back to 1919, has more than 2,700 employees including nearly 300 partners and is a member of Nexia International, a global network of independent accountancy, tax, and business advisors. The Firm’s Renewable Energy Industry Practice helps clients navigate the industry’s nuanced business, regulatory, and financial issues. The Practice’s integrated service platform includes assurance and attestation, technical accounting consulting, tax and advisory structuring, and advisory (IPO readiness, YieldCo, valuation, transactional, capital markets) services.

The team includes more than 40 highly experienced professionals with deep industry credentials. About CohnReznick Capital Markets Securities (CRCMS): CRCMS offers a comprehensive financial advisory platform for the renewable energy and sustainability industries, including solutions for corporations that includes corporate financing, project financing and M&A advisory. The company represents financial institutions, infrastructure funds, strategic participants (IPPs and utilities) and the leading wind, solar, biomass and other alternative energy developers nationwide. CRCMS has successfully executed sale placements and asset sales for more than 896 MW of solar and 2,023 MW of wind projects, and more than $5 billion in tax equity investments. Contact our renewable energy team for more information: Anton Cohen Rob Sternthal Co-National Director, Renewable Energy Industry CohnReznick LLP 301-280-1822 anton.cohen@CohnReznick.com President, CohnReznick Capital Markets Securities LLC 917-472-1272 rob.sternthal@crcms.com Timothy Kemper Co-National Director, Renewable Energy Industry CohnReznick LLP 404-847-7764 timothy.kemper@CohnReznick.com cohnreznick.com cohnreznickcapmarkets.com CohnReznick is an independent member of Nexia International This has been prepared for information purposes and general guidance only and does not constitute professional advice.

You should not act upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is made as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this publication, and CohnReznick LLP, its members, employees and agents accept no liability, and disclaim all responsibility, for the consequences of you or anyone else acting, or refraining to act, in reliance on the information contained in this publication or for any decision based on it. .

Also referred to as shared renewables, community renewables, or even solar ‘gardens’, community solar is an energy procurement model that allows private companies, institutions and individuals to aggregate their electricity load to purchase clean energy on behalf of those who wish to participate. The model offers an alternative to rooftop solar for both individuals and businesses wishing to benefit from the stable pricing and green credentials that renewable energy affords but can’t because their rooftops are not suitable for solar panels or they are renters. Community solar works in partnership with local utilities, which continue to deliver power, maintain the grid, and may provide consolidated billing and other customer services. However, the customers pay a community solar project instead of the utilities and receive credits on their electricity bills for the power procured. Community solar projects can be developed and owned by utilities or other third parties. Customers can either pay upfront for a portion of the project’s output or for a portion of a project’s capacity. Further, customers can either pay an entire amount up front or pay periodically, such as monthly. .

Page 3 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 ENABLING LEGISLATION CREATES HUGE GROWTH POTENTIAL The market potential for community solar is huge. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates community solar could represent 32%-49% of the distributed PV market by 2020. This equates to cumulative 5.5-11.0 GW of capacity projected to be brought online between 2015 and 2020, or between $8.2 billion and $16.3 billion of cumulative investment1. As shown in the graph below, it is unlikely that more than 1 GW of community solar projects will be brought online this year or next. But in 2020, potentially, more than 4GW of community solar projects could be installed. 1 David Feldman, Anna M.

Brockway, Elaine Ulrich, and Robert Margolis, Shared Solar: Current Landscape, Market Potential, and the Impact of Federal Securities Regulation, (April 2015), www.nrel.gov/docs/fy15osti/63892.pdf p.v Estimated market potential of onsite and shared solar distributed PV capacity 10 Annual US PV Demand (GW) 9 8 7 6 5 Shared Solar GW (Historic) 4 Shared Solar GW (High) 3 Shared Solar GW (Low) 2 Distributed PV Market 1 0 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Source: National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) The rapid rate of community solar development that followed the implementation of enabling legislation highlights its potential. Take the state of Minnesota as an example. Minnesota passed the Solar Energy Jobs Act in 2013, a key piece of enabling legislation that made community solar commercially viable.

At the time, only 14 MW of community solar had been installed state-wide. As Karen Gados, Business Development Manager at SunShare explains, development activity skyrocketed following the legislation. “Within the first week of the community solar program opening, the state received over 400 applications for approximately 458 MW of capacity,” she said. “To date, they have received 2 GW.” What is driving community solar growth? Without doubt, the most important factor is the establishment of enabling legislation that allows projects to sell power to multiple offtakers - residents, municipalities, or businesses (so-called third-party PPAs). The legislation may also allow customers of community solar projects to receive monetary or electricity credits to offset their electricity bills.

The type of legislation that enables crediting depends on the dynamics of the market. It could include a specific community solar program or virtual net metering. Also, these offsets may be at wholesale or retail rates, or somewhere in between. .

Page 4 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 To date, fourteen states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) have adopted some form of shared renewable initiatives. Many more are considering programs, including New Mexico and Virginia. The leading programs are outlined in the table below. Some of these programs are in their pilot stages and are limited, usually by the megawatts deployed. STATE “Initially, the regulatory environment was the catalyst for shared solar adoption,” explained Tim Braun, Director of Public Affairs at Clean Energy Collective.

“Today, the market is also active in states yet to adopt specific community solar legislation. Consumer demand has grown exponentially with more understanding and awareness of the model and benefits.” POLICY YEAR ENACTED California Virtual Net Metering for Multi-Tenant Buildings Green Tariff Shared Renewables Program Colorado Community Solar Gardens Act HB 1284 - Expand Scope of Shared Photovoltaic Facilities 2010 2015 Connecticut Virtual Net Metering An Act Establishing a Shared Clean Energy Facility Pilot Program - SB 928 2013 2015 Delaware Community Net Metering Provisions 2010 Hawaii SB1050 / HB484: An Act Relating to Energy 2015 Maine Net Energy Billing to Allow Shared Ownership 2012 Maryland Electricity - Community Energy-Generating Facilities - Pilot Program - HB 1087 / SB 481 2015 Massachusetts Green Communities Act (SB 2768) Neighbourhood Net Metering 2008 2013 Minnesota Solar Energy Jobs Act (HF 729) 2013 New Hampshire Group Net Metering 2013 New York PSC Order Establishing a Community DG Program 2015 Oregon House Bill 2941 - Relating to solar energy, creating new provisions 2015 Vermont Group Net Metering Net Metering Amendments H.702 2012 2014 Washington Community Renewables Enabling Act 2010 Washington, D.C. Community Renewable Energy Act of 2013 Source: Shared Renewables HQ/ Clean Energy Pipeline 2009/11 2013 2011/13 . Page 5 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 FINANCING COMMUNITY SOLAR Tried and tested tax equity financing structures have evolved for conventional renewable energy projects. Can these be applied to community solar projects? The consensus today is that there is no reason why they can’t. However, investors need to be educated on and get comfortable with the different risk profile. The primary difference between standard and community solar projects is the offtaker. Instead of a single creditworthy utility offtaker taking physical delivery of the power community projects have several if not hundreds of individual offtakers with varying credit ratings that do not take physical delivery of the power. Any number of offtakers may elect to drop out of the program, thus creating a revenue shortfall.

One way to alleviate dropout risk is to create a community renewable program that is oversubscribed. Subscribers on the waiting list can then instantly replace those leaving the program, ensuring the revenue stream is maintained. Alternatively, underwriters may evaluate the project assuming a certain percentage of revenue simply will not be collected, which can account for temporary losses of revenue as customers turn over. “In the event of a customer default, we can easily change an account number on a database from a defaulted customer to a new customer,” explained Christopher Sayer, Finance Director at SunShare.

“As a result, it’s much easier to cure a default. We’ve found that resonates well with the financial community. Rather than being a single offtake utility PPA, we have a portfolio effect with a plethora of customers.

This de-risking means that, in many ways, financing community projects is lower risk than traditional rooftop solar.” Questions do remain regarding the level of oversubscription that investors need to advance financing and whether they are prepared to advance funds before this level has been obtained. “There are still questions about how quickly a system will develop a minimum subscriber base to make a particular project feasible,” said Joel Cohn, Partner at CohnReznick. “Investors need to consider the point at which they advance funds and step into that risk position.

There are also questions about customer turnover, managing waiting lists, and replacing customers and their revenue streams with new customers. These are not serious risks but they are different risks to the traditional solar financing model.” THE UTILITY VIEWPOINT – CHALLENGE OR OPPORTUNITY? The community solar model disrupts the traditional relationship between utilities and their customers, creating both challenges and opportunities for incumbent power generators. On the one hand, community solar might cause headaches for utilities if it creates pressure on the grid resulting from a surge in solar projects. “The rise of community solar creates extra work for utilities.

They must undertake engineering studies, review the grid readiness for more renewables penetration, and process project applications in a quick timeframe,” explained Gados. “It has been a point of discussion. How can community solar companies and utilities successfully navigate through these engineering and connection studies and how much solar can we really put on the grid?” In some states such as Colorado, the regulatory environment allows utilities to recover some of these costs.

But in other states, utilities cannot recover these costs. “If utilities are no longer providing electricity to the consumer, but the consumer is connected to the grid as a back-up source, they may want to charge the consumer for grid investment and maintenance,” notes Joel Cohn, Partner at CohnReznick. “They still have a significant investment and must maintain that equipment so they may want to be compensated for those costs.

There may be a wide variety of options as to how these costs and credits are reflected on community solar consumer’s bills – full retail, disaggregated retail- value of solar and others – I think that is a critical but very much evolving issue.” On the other hand, community solar offers an opportunity for utilities to address the growing threat of homeowners going completely off the grid and cutting ties with utilities by installing rooftop solar and battery storage. For some . Page 6 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 homeowners, community solar may be a more compelling alternative to installing panels on their roof if it is offered by utilities. “Community solar is a huge opportunity for utilities because, unlike traditional rooftop solar, it allows them to hold on to their customer base because the customer never leaves the grid,” says Gados. “In a traditional community solar program, the customer stays connected to the grid and simply receives credit on their bill in return for their purchase of the solar energy subscription. This is less intimidating to utilities because they are not at risk, as they are with rooftop customers, of them suddenly cutting ties with utilities.” Given the complexities of community solar, many utilities were evaluating how their competitors embraced this new business model before fully committing. “Lots of utilities were in a wait and see mode, wanting to see how others integrated it,” explained Tim Braun, Director of Public Affairs at Clean Energy Collective. “But many are starting to transition from observing to engaging because they are seeing success.” If a utility decides that it does want to get involved with community solar, the next question is how. UTILITY One option is for the utility to do everything themselves, from developing and operating the project to customer acquisition, billing and credit management.

This approach was adopted by Tucson Electric Power (TEP) for its Bright Tucson Community Solar Program. The program offers TEP customers the opportunity to purchase solar in 150 KWh blocks, which then offset the need for conventional electricity sources. Each block costs $3.00 per month but these blocks are exempt from certain surcharges.

This means that the additional cost is actually lower. Each block replaces the charges for an equivalent amount of conventional power. The Bright Tucson Community Solar Program is currently oversubscribed. Alternatively, utilities can partner with specialist community solar companies capable of handling both customer acquisition and billing and credit management.

For example, NRG Renew, a subsidiary of NRG Energy, formed a partnership with SunShare in January 2015 to finance and build an 8.2 MW portfolio of community solar projects in Colorado. The projects came online last year. NRG already owned a portfolio of community wind and solar projects before this partnership was formed. Some notable utility-led community programs are outlined in the table below: COMMUNITY SOLAR PROGRAM PARTNERS Tucson Electric Power Tucson, Arizona Bright Tucson Community Solar N/A Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) Sacramento, California SolarShares Program N/A United Power Brighton, Colorado Sol Partners Cooperative Solar Farm N/A Green Mountain Power Colchester, Vermont Community Solar NRG Home Solar Xcel Energy Minneapolis, Minnesota Solar*Rewards Community NRG Home Solar, Minnesota Community Solar, SunShare Colorado Springs Utilities Colorado Springs, Colorado Pikes Peak Solar Garden Clean Energy Collective, SunShare Source: Clean Energy Pipeline .

Page 7 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 “Community solar is beginning to flourish. Financing partners are getting comfortable with it and it’s attractive because it de-risks the biggest issue with residential solar: non-payment. Most community solar projects are oversubscribed so someone else can step in and pay if this problem occurs. The more forward thinking utilities understand that community solar is their opportunity to work with their customer base in a proactive and efficient way.” Conor McKenna, Managing Director, CohnReznick Capital Markets Securities, LLC ROOFTOP SOLAR – FRIEND OR FOE? The US rooftop solar market is booming. The Solar Energy Industries Association estimates that, for the first time ever, more than 2 GW of residential solar was installed in 2015, significantly more than in 2014.

If rooftop and community solar are in competition, this growth might stunt the rise of community solar before it has taken off. On the flip side, a surge in community solar might slow the growth of rooftop solar. The industry professionals interviewed for this report believe that community and rooftop solar are often not in direct competition. This is primarily because rooftop solar is not logistically possible for such a large number of households. In fact, The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates that 49% of households in the US are currently unable to host a PV system (after excluding those that do not own their building and those without access to sufficient roof space.)2 Therefore, half of all households in the US do not have the choice of whether to install solar on their roof or sign up for a community solar program, but instead are limited to a choice between community solar and no solar at all. Even for households that can accommodate rooftop solar, community solar could be a more 2 appealing option because it is more flexible. “With rooftop solar, you have an agreement that offers financial savings but it’s also a rigid commitment,” said Sandy Roskes, Senior Vice President of New Ventures at Ethical Electric.

“You either need to buy the asset and hold it long-term or you need to enter into a long-term financial arrangement. In addition to community solar being an option for households that cannot accommodate rooftop solar, it also enables individuals to decide how much capital they want to commit, and for how long, in a way that rooftop can’t.” Some community solar companies consider the market opportunity to be so extensive that they do not target households with rooftops suitable for solar. “The 2015 NREL report on shared solar stated around half of people can’t participate in rooftop solar.

But we think it’s safe to say that anywhere between 50-80% of people can’t accommodate rooftop solar,” explained Gados. “Those are the folks that we are targeting. If we get a phone call from someone asking for solar on their rooftop we will usually refer them to someone at the local solar association.

We don’t view the rooftop industry as competition in any shape or form.” David Feldman, Anna M. Brockway, Elaine Ulrich, and Robert Margolis, Shared Solar: Current Landscape, Market Potential, and the Impact of Federal Securities Regulation, (April 2015), www.nrel.gov/docs/fy15osti/63892.pdf p.v . Page 8 North America Renewable Energy Brief – March 2016 WHAT DOES COHNREZNICK THINK? The community solar model is gathering momentum. The projections made by the NREL and the Department of Energy that were mentioned earlier make this abundantly clear. The question is, therefore, not whether this market will grow but by how much. And what will the impact be on incumbent players - notably the utilities and rooftop solar companies. The examples highlighted earlier demonstrate that forward thinking utilities can benefit hugely from engaging with community solar. Of course, careful consideration needs to be given to how projects are structured and the extent to which key aspects of the projects, such as customer acquisition and management, are outsourced to partners.

But if structured correctly, community solar should enable utilities to retain a healthy relationship with their customers. There is also the question of financing. Our view is that, ultimately, the structures that have been used for many years can be applied to community projects. Of course the risk profile is different. For a start, community projects rely on multiple virtual offtakers that, at any point, may choose to exit the program.

This risk could be minimized depending upon how the program is structured. But the unique features of community solar are also, in many ways, less risky to investors. Projects can manage waiting lists of customers, with any defaults being rectified fairly easily. As always, we recommend seeking professional advice to help navigate through these issues and welcome all conversation in response to this paper. About CohnReznick: CohnReznick LLP is one of the top accounting, tax, and advisory firms in the United States, combining the resources and technical expertise of a national firm with the hands-on, entrepreneurial approach that today’s dynamic business environment demands.

Headquartered in New York, NY, and with offices nationwide, CohnReznick serves a large number of diverse industries and offers specialized services for middle market and Fortune 1000 companies, private equity and financial services firms, government contractors, government agencies, and not-for-profit organizations. The Firm, with origins dating back to 1919, has more than 2,700 employees including nearly 300 partners and is a member of Nexia International, a global network of independent accountancy, tax, and business advisors. The Firm’s Renewable Energy Industry Practice helps clients navigate the industry’s nuanced business, regulatory, and financial issues. The Practice’s integrated service platform includes assurance and attestation, technical accounting consulting, tax and advisory structuring, and advisory (IPO readiness, YieldCo, valuation, transactional, capital markets) services.

The team includes more than 40 highly experienced professionals with deep industry credentials. About CohnReznick Capital Markets Securities (CRCMS): CRCMS offers a comprehensive financial advisory platform for the renewable energy and sustainability industries, including solutions for corporations that includes corporate financing, project financing and M&A advisory. The company represents financial institutions, infrastructure funds, strategic participants (IPPs and utilities) and the leading wind, solar, biomass and other alternative energy developers nationwide. CRCMS has successfully executed sale placements and asset sales for more than 896 MW of solar and 2,023 MW of wind projects, and more than $5 billion in tax equity investments. Contact our renewable energy team for more information: Anton Cohen Rob Sternthal Co-National Director, Renewable Energy Industry CohnReznick LLP 301-280-1822 anton.cohen@CohnReznick.com President, CohnReznick Capital Markets Securities LLC 917-472-1272 rob.sternthal@crcms.com Timothy Kemper Co-National Director, Renewable Energy Industry CohnReznick LLP 404-847-7764 timothy.kemper@CohnReznick.com cohnreznick.com cohnreznickcapmarkets.com CohnReznick is an independent member of Nexia International This has been prepared for information purposes and general guidance only and does not constitute professional advice.

You should not act upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is made as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this publication, and CohnReznick LLP, its members, employees and agents accept no liability, and disclaim all responsibility, for the consequences of you or anyone else acting, or refraining to act, in reliance on the information contained in this publication or for any decision based on it. .