Description

Consultation Paper

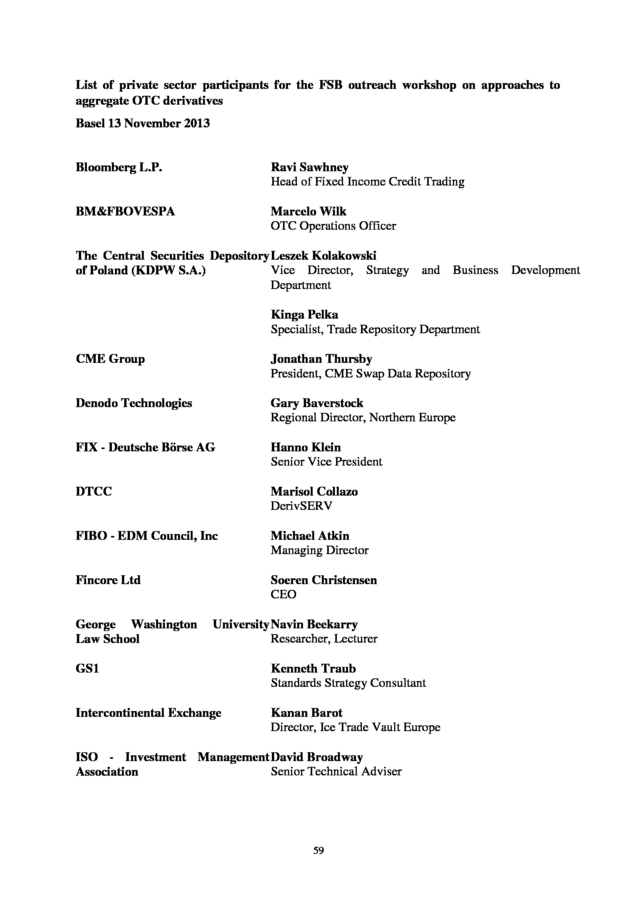

Feasibility study on approaches

to aggregate OTC derivatives data

4 February 2014

.

. Preface

Feasibility study on approaches to aggregate

OTC derivatives trade repository data

Public consultation paper

G20 Leaders agreed, as part of their commitments regarding OTC derivatives reforms, that all

OTC derivatives contracts should be reported to trade repositories (TRs). The FSB was

requested to assess whether implementation of these reforms is sufficient to improve

transparency in the derivatives markets, mitigate systemic risk, and protect against market

abuse.

A good deal of progress has been made in establishing the market infrastructure to support the

commitment that all contracts be reported to TRs. However, the data will be reported to

multiple TRs located in a number of jurisdictions. The FSB therefore requested further study

of how to ensure that the data reported to TRs can be effectively used by authorities, including

to identify and mitigate systemic risk, and in particular through enabling the availability of the

data in aggregated form.

The FSB, in consultation with the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems (CPSS) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), will then make a decision on whether to initiate work to develop a global aggregation mechanism and, if so, according to which type of aggregation model and which additional policy actions may be needed to address obstacles. The attached public consultation paper responds to the request by the FSB for a feasibility study that sets out and analyses the various options for aggregating OTC derivatives TR data. The draft has been prepared by a study group set up by the FSB and composed of experts from member organisations of CPSS and IOSCO and other organisations with roles in macroprudential and microprudential surveillance and supervision. The paper discusses the key requirements and challenges involved in the aggregation of TR data, and proposes criteria for assessing different aggregation models. Following this public consultation and further analysis by the study group, a finalised version of the report, including recommendations, will be submitted to the FSB in May 2014 for approval and published thereafter. The public consultation paper examines the three broad types of model for an aggregation mechanism: a physically centralised model; a logically centralised model; and the collection and aggregation by authorities themselves of raw data from TRs. Within these three broad types of model, a variety of detailed alternatives exist that would provide differing levels of sophistication of service.

These alternatives would need to be examined further in the final report in May and in any follow-on work that may be commissioned to take forward one of models following this feasibility study. i . The study is focusing on the feasibility of options for data aggregation in the current regulatory and technological environment and given the existing (and planned) global configuration and functionality of TRs. The aggregation options are being considered on the basis that they would complement, rather than replace, the existing operations of TRs and authorities’ existing direct access to TR data. The paper analyses the key factors and challenges associated with the three models, taking into account the range of needs of authorities for aggregated data across TRs and focusing on those considerations that are most relevant to the potential choice of model. It divides these considerations into two types: • legal considerations, including those relating to submission of data to the aggregation mechanism, access to the mechanism, and governance of the mechanism: and • data and technology considerations, including those related to data standardisation and harmonisation, data quality, information security, and other technological considerations. Based on this analysis, the paper proposes a set of criteria to be used in order to provide a common and systematic structure for the assessment of the options in the final report. The paper does not at this stage propose draft conclusions or recommendations for the final report. The FSB wishes to have feedback via this public consultation process on these considerations and criteria before proceeding to the assessment itself.

The feedback received will inform the further analysis by the FSB study group regarding the aggregation solutions, the constraints, and the methodology to be followed for the assessment. The FSB invites comments in particular on the following questions: 1. Does the analysis of the legal considerations for each option cover the key issues? Are there additional legal considerations - or possible approaches that would mitigate the considerations - that should be taken into account? 2. Does the analysis of the data and technology considerations cover the key issues? Are there additional data and technology considerations - or possible approaches that would mitigate those considerations - that should be taken into account? 3.

Is the list of criteria to assess the aggregation options appropriate? 4. Are there any other broad models than the three outlined in the report that should be considered? 5. The report discusses aggregation options from the point of view of the uses authorities have for aggregated TR data.

Are there also uses that the market or wider public would have for data from such an aggregation mechanism that should be taken into account? Responses should be sent by Friday 28 February 2014 to fsb@bis.org with “AFSG comment” in the e-mail title. Responses will be published on the FSB’s website unless respondents expressly request otherwise. ii . Table of Contents Page Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1 – Objectives, Scope and Approach ............................................................................ 5 1.1 Objective of the Study ................................................................................................

5 1.2 Scope of the Study...................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Aggregation Models Analysed ................................................................................... 5 1.4 Preparation of the Study .............................................................................................

8 1.5 Definition of Data Aggregation.................................................................................. 8 1.6 Assumptions ............................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 2 – Stocktake of Existing Trade Repositories ..............................................................

9 2.1 TR reporting implementation and current use of data................................................ 9 2.2 Available data fields and data gaps .......................................................................... 11 2.3 Data standards and format ........................................................................................

11 2.4 Legal and privacy issues .......................................................................................... 12 Chapter 3 – Authorities’ Requirements for Aggregated OTC Derivatives Data ..................... 12 3.1 3.1 Data Needs .........................................................................................................

12 3.2 Aggregation Minimum Prerequisites ....................................................................... 14 3.3 Further aggregation requirements ............................................................................ 17 Chapter 4 – Legal Considerations ............................................................................................

19 4.1 Types of existing legal obstacles to submit/collect data from local trade repositories into an aggregation mechanism ............................................................................................ 21 4.2 Legal challenges to access to TR data ...................................................................... 23 4.3 Legal considerations for the governance of the system ...........................................

24 Chapter 5 – Data & Technology Considerations ..................................................................... 29 5.1 The Impact of the Aggregation Option on Data and Technology ............................ 29 5.2 Data aggregation and reporting framework .............................................................

30 5.3 Data reporting ........................................................................................................... 30 5.4 Principles of data management to facilitate proper data aggregation ...................... 31 5.5 Principles of data management regarding the underlying data ................................

31 5.6 Principles of data management regarding the technological arrangements ............. 38 1 . Chapter 6 – Assessment of Data Aggregation Options ............................................................ 40 Chapter 7 – Concluding Assessment ........................................................................................ 42 Appendix 1: Feasibility study on approaches to aggregate OTC derivatives data .................. 43 Appendix 2: Summary of the outreach workshop ...................................................................

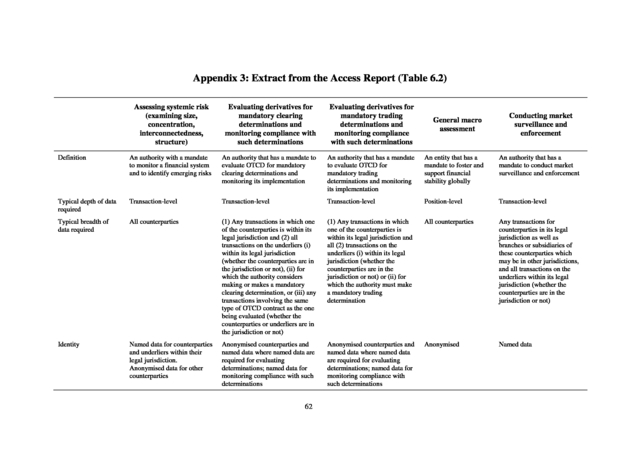

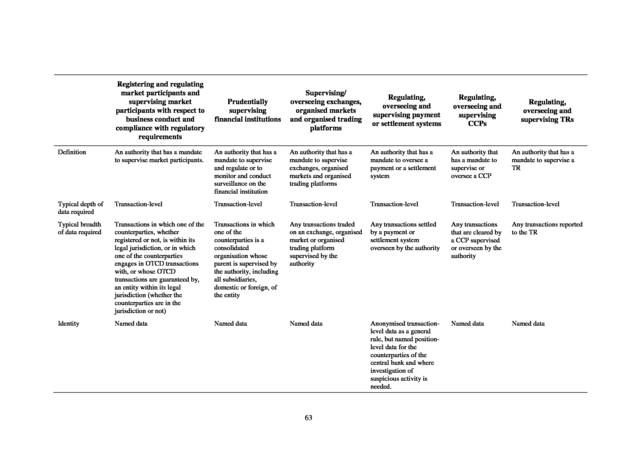

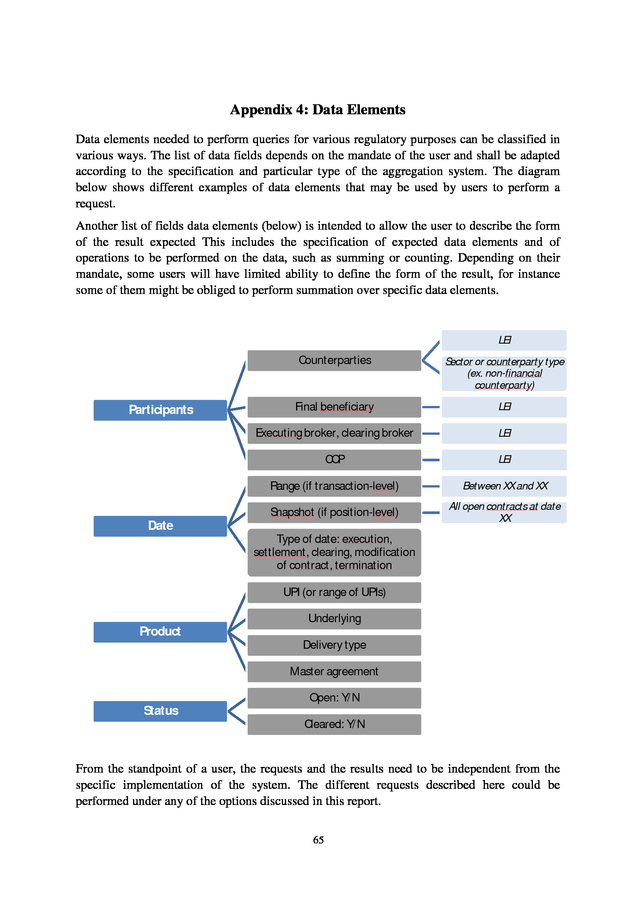

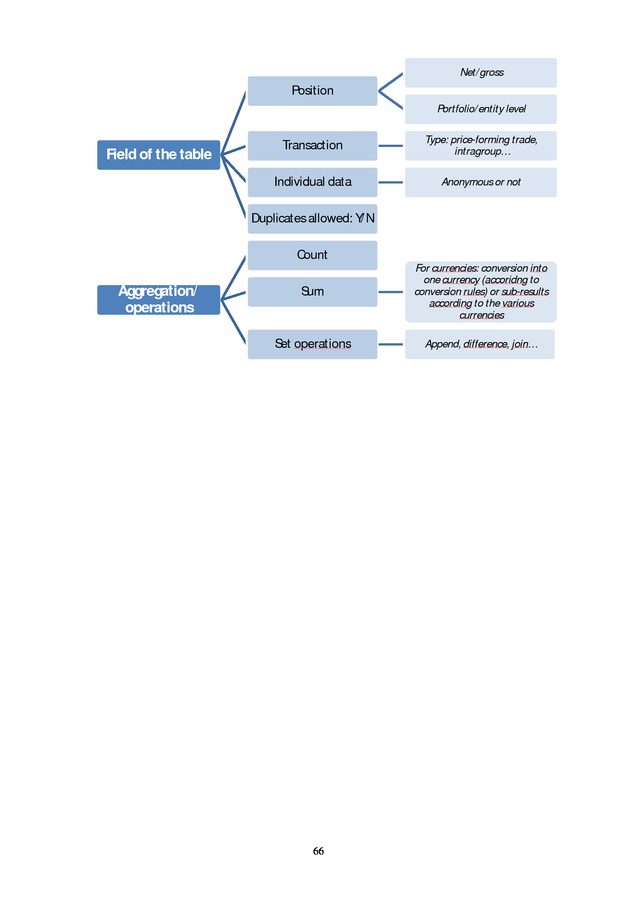

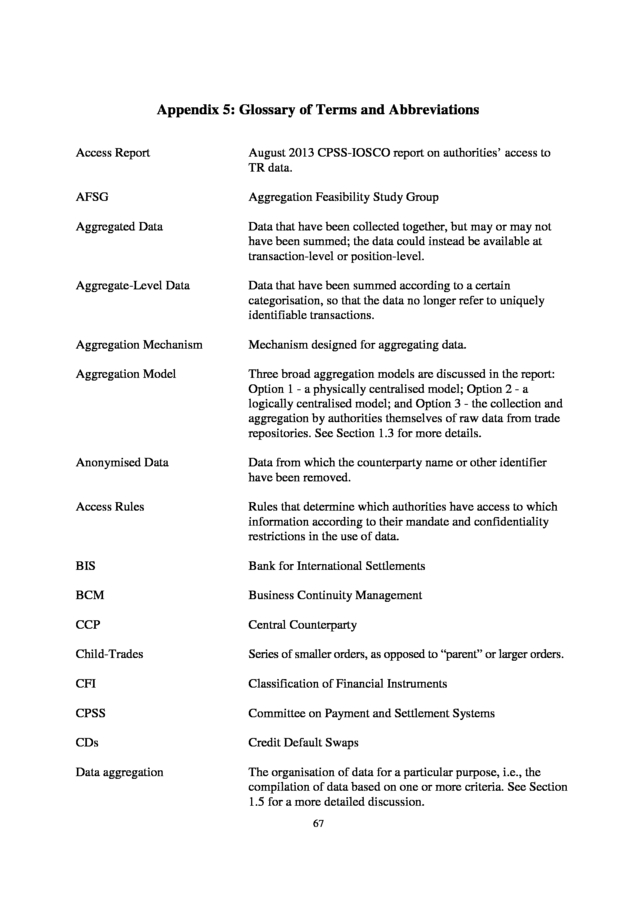

51 Appendix 3: Extract from the Access Report (Table 6.2) ....................................................... 62 Appendix 4: Data Elements ..................................................................................................... 65 Appendix 5: Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations ................................................................

67 Appendix 6: Members of Workshop ....................................................................................... 70 Appendix 7: List of References ............................................................................................... 73 2 .

Executive Summary This section will contain a summarised version of the entire report targeted for a quick and comprehensive read [to be added after consultation]. Introduction G20 Leaders agreed, as part of their commitments regarding OTC derivatives reforms, that all OTC derivatives contracts should be reported to trade repositories (TRs). The FSB was requested to assess whether implementation of these reforms is sufficient to improve transparency in the derivatives markets, mitigate systemic risk, and protect against market abuse. A good deal of progress has been made in establishing the TR infrastructure to support the commitment that all contracts be reported. Currently, multiple TRs operate, or are undergoing approval processes to do so, in a number of different jurisdictions. The requirements for trade reporting differ across jurisdictions.

The result is that TR data are fragmented across many locations, stored in a variety of formats, and subject to many different rules for authorities’ access. The data in these TRs will need to be aggregated in various ways if authorities are to obtain a comprehensive and accurate view of the global OTC derivatives markets and to meet the original financial stability objectives of the G20 in calling for comprehensive use of TRs. The FSB, CPSS and IOSCO have identified the need for further study of how to ensure that the data reported to TRs can be effectively used by authorities, including to identify and mitigate systemic risk, and in particular through enabling the availability of the data in aggregated form. The FSB set up a group - the Aggregation Feasibility Study Group (AFSG) to study the feasibility of several options to produce and share the types of global aggregated TR data that authorities need to fulfil their mandates and to monitor financial stability, taking into account legal and technical issues.

The FSB’s terms of reference for the study are attached as Appendix 1. This draft report takes as a starting point existing international guidance and recommendations relating to TRs, including those contained in the January 2012 CPSSIOSCO report on OTC derivatives data reporting and aggregation requirements (“Data Report”) and the August 2013 CPSS-IOSCO report on authorities’ access to TR data (“Access Report”). It has also made use of the semi-annual FSB progress reports on the implementation of OTC derivatives market reforms, including on the implementation of comprehensive trade reporting requirements. Structure of the Report The report is structured as follows. Chapter 1 lays down the objectives, scope and approach followed by the feasibility study. Chapter 2 makes a brief stock-take of the current status of TR implementation, including the current and planned global configuration of TRs, in order to provide background on the scale and scope of the aggregation challenges. 3 . Chapter 3 summarises the different types of requirements of authorities for aggregated OTC derivatives data, focusing in particular on the minimum pre-requisites for aggregation in order that the data are useable by authorities to fulfil their various mandates. Chapter 4 describes the legal and policy considerations, concerning submission of and access to data and governance of the aggregation mechanism, that are relevant to the choice of aggregation model. Chapter 5 discusses the data and technology considerations associated with meeting authorities’ requirements for aggregated data under the different choices of model. Chapter 6 presents the criteria for the assessment of the options derived from the discussion in Chapters 3, 4 and 5, and (to be drafted for the final version of the report following public consultation) the assessment of the pros and cons of the different aggregation options against those criteria. Chapter 7 (to be drafted for the final version of the report following the public consultation) will conclude with the overall recommendations of the study, as well as pointing to policy areas that might need further attention from the FSB, standard setters or jurisdictions, and areas where further study may be needed. This consultative draft report has been prepared by the AFSG and approved for publication by the FSB. The FSB invites comments on the analysis contained in this consultative report and in particular on the following points: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Does the analysis of the legal considerations for each option cover the key issues? Are there additional legal considerations - or possible approaches that would mitigate the considerations - that should be taken into account? Does the analysis of the data and technology considerations cover the key issues? Are there additional data and technology considerations - or possible approaches that would mitigate those considerations - that should be taken into account? Is the list of criteria to assess the aggregation options appropriate? Are there any other broad models than the three outlined in the report that should be considered? The report discusses aggregation options from the point of view of the uses authorities have for aggregated TR data. Are there also uses that the market or wider public would have for data from such an aggregation mechanism that should be taken into account? Responses should be sent by Friday 28 February 2014 to fsb@bis.org with “AFSG comment” in the e-mail title. Responses will be published on the FSB’s website unless respondents expressly request otherwise. The feedback received will be taken into account in the finalised version of the report, which will be provided to the FSB in May 2014 and subsequently published by the FSB. 4 .

1. Chapter 1 – Objectives, Scope and Approach 1.1 Objective of the Study The goal of this feasibility study is to set out and analyse the various broad options for aggregating TR data for use by authorities in effectively meeting their respective mandates. The FSB, in consultation with CPSS and IOSCO, will then make a decision on whether to initiate work to develop a global aggregation mechanism and, if so, according to which type of aggregation model and which additional policy actions may be needed to address obstacles. The report is structured so that the final version in May will provide the relevant information for senior policy-makers to be able to make the above decisions, and to inform both senior policy-makers and the public about the analysis supporting that information. 1.2 Scope of the Study For each option, the final version of the report will: • set out the key steps necessary to develop and implement the option, • review the associated legal and technical issues, and • provide a description of the strengths and weaknesses of the option, taking into account the types of aggregated data that authorities may require and the uses to which authorities might put the data. The study is intentionally high-level in approach, comparing the effectiveness of the broad types of options that could be used in meeting the G20 goal that authorities are able to have a global view of the OTC derivatives markets. It does not attempt to analyse the specific technological choices of hardware and software, or define the specific legal and governance requirements. At this early stage of the analysis of the options, with so many elements of the scope and scale of the exercise still undefined, it is not possible to estimate the costs of the different options. The report includes instead a qualitative analysis of the relative complexity of the different options.

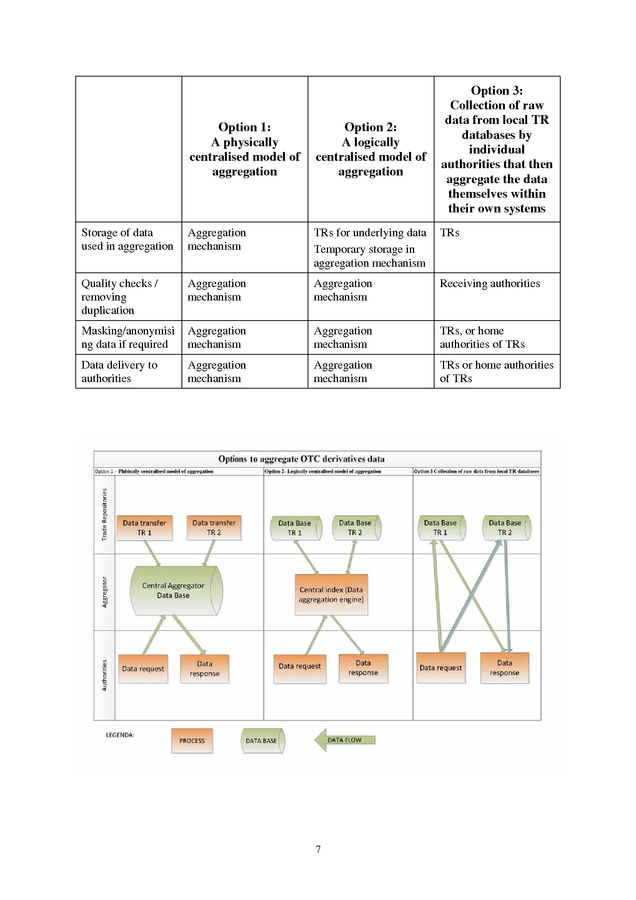

More detailed work on such issues is expected to take place in any follow-on work that may be commissioned by policy-makers. 1.3 Aggregation Models Analysed The main options for aggregating TR data explored by this study are: Option 1. A physically centralised model of aggregation. This model would feature a central database where required transaction and (if needed and available) position and collateral data would be collected from TRs and stored on a regular basis.

The facility housing the database would provide services to report aggregated data to authorities, drawing on the stored underlying transaction, position and collateral details. In order to do so, the facility would perform functions such as data quality checks, removing duplications, and masking or anonymising data as needed. Reports and underlying data would be available to authorities as needed and permitted according to a separate database of individual authorities’ access rights. Option 2.

A logically centralised model of aggregation. This model would feature federated (physically decentralised) data collection and storage of the same types of data as in Option 1. It would not physically collect or store data from TRs (other than temporary local caching 5 . where necessary in the aggregation process). Instead it would rely on a central logical catalogue/index to identify the location of data resident in the TRs, which would assist individual authorities in obtaining data of interest to them. In this model, the underlying data would remain in local TR databases and be aggregated via logical centralisation by the aggregation mechanism, being retrieved on an “as needed” basis at the time the aggregation program is run. 1 Either Option 1 or Option 2 could be implemented with varying degrees of sophistication or service levels, ranging from basic delivery of data in response to each request to - at its most sophisticated – providing additional services beyond basic delivery of data, such as performing quality checks/removing duplications, masking/anonymising data according to the mandate/authorisation of the requester, and aggregating data. The less ambitious versions of Options 1 and 2 would be less complex to implement but would not deliver the full range of services and meet the full range of uses of data that authorities seek in order to meet their mandates.

The final version of this report in May will include an evaluation of the extent to which less ambitious versions of each option could meet the range of user requirements. Option 3. Collection of raw data from local TR databases by individual authorities that then aggregate the data themselves within their own systems. Under this option, there would be no central database or catalogue/index.

All the functions of access rights verification, quality checks, etc., would be performed by the requesting authority and the responding authorities or TRs on a case-by-case basis. Access would be granted based on the rules and legislation applicable to each individual TR. (Option 3 represents the current situation for authorities wishing to aggregate data.

As noted later in this report, truly global and comprehensive data aggregation is not possible under current arrangements as no individual authority or body has comprehensive access to all data in all TRs. Under Option 3, authorities could expand their cross-border access to data from current levels by concluding additional international agreements, but the absence of a centralised aggregation mechanism would seem to preclude the provision of some forms of aggregated data, notably anonymised counterparty-level data.) In this report, the term “aggregation model” is used to refer to any one of the three options above. The term “aggregation mechanism” refers to mechanisms modelled on Option 1 and Option 2 as described above. The table below summarises the division of roles under the different aggregation models in performing the main tasks involved in aggregation, and the accompanying diagram provides a visual representation. 1 Within Option 2, data normalisation and reconciliation can be performed at a centralised or at a decentralised level.

Such sub-options do not fundamentally impact the following analysis and discussion. 6 . Option 3: Collection of raw data from local TR databases by individual authorities that then aggregate the data themselves within their own systems Option 1: A physically centralised model of aggregation Option 2: A logically centralised model of aggregation Storage of data used in aggregation Aggregation mechanism TRs for underlying data Temporary storage in aggregation mechanism TRs Quality checks / removing duplication Aggregation mechanism Aggregation mechanism Receiving authorities Masking/anonymisi ng data if required Aggregation mechanism Aggregation mechanism TRs, or home authorities of TRs Data delivery to authorities Aggregation mechanism Aggregation mechanism TRs or home authorities of TRs 7 . 1.4 Preparation of the Study The design of the study, including the diverse expertise within the AFSG, public consultation on the draft report, publication of the final report, is intended to ensure that the policy-makers have the benefit of a wide range of input before deciding upon the next steps, including which option to pursue. In preparing the draft the AFSG has used a variety of sources, including: • a survey of authorities in FSB member jurisdictions to gather additional information on the OTC derivatives data currently reported to TRs and accessed by authorities, as well as the status of their data aggregation capabilities on both local and global levels; • a workshop to discuss technical and legal issues in relation to the implementation of the alternative options, bringing together members of the AFSG and experts in the data, IT and legal issues involved, from inside and outside the financial industry (see Appendix 2); • existing reports and studies (see full list of references in Appendix 6). 1.5 Definition of Data Aggregation This report uses the Data Report definition of data aggregation “as the organisation of data for a particular purpose, i.e., the compilation of data based on one or more criteria”. Data aggregation may or may not involve logical or mathematical operations such as summing, filtering and comparing. As noted in the Access Report, authorities (depending on their mandates) may require access to aggregated data: • at three levels of depth: 1. Transaction-level (data specific to uniquely identified market participants and transactions) 2. Position-level (gross or netted open positions specific to a uniquely identified participant or pair of participants) 3. Aggregate-level (summed data according to various categories, e.g. by product, maturity, currency, geographical region, type of counterparty, underlier, that are not specific to any uniquely identifiable participant or transaction) • according to a certain level of breadth (in terms of scope of participants and products/underliers) • and according to a certain level of identity (named versus anonymous). 2 An important distinction in terminology therefore exists between the terms “aggregated data” and “aggregate-level data”.

“Aggregated data” are data that have been collected together, but may or may not have been summed; the data could instead be available at transaction-level or position-level. This process of collecting the data together is referred to as “data aggregation”. 2 More detail on the concepts of depth, breadth and identity is available in the Access Report. 8 . “Aggregate-level” data, on the other hand, are data that have been summed according to a certain categorisation so that the data no longer refer to uniquely identifiable transactions. Different authorities (or the same authority at different times) will require access at different levels of depth, breadth and identity for different purposes. The aggregation mechanism will need to be flexible enough to provide authorities with the level of access that they require and are entitled to for these different purposes. Chapter 3 discusses these data needs and how they affect aggregation requirements in more detail. 1.6 Assumptions The study focuses on the feasibility of options for data aggregation in the current regulatory and technological environment and given the existing (and planned) global configuration of TRs. In particular, the study is based on the following assumptions: • that comprehensive reporting of OTC derivatives trades is achieved in the major jurisdictions, in accordance with the G20 commitment, • that TRs operate under their existing functionality and data collection practices, • that the aggregation option being considered would complement, rather than replace, the existing operations of TRs and authorities’ existing direct access to TR data. The study does not set out to propose changes to the data reported to TRs or the data held by TRs unless those changes are necessary or desirable to achieve aggregation.

However, where needed, the study highlights any regulatory or other actions that might be needed in order to enable an option to be implemented or to improve its effectiveness. It notes where relevant improvements in market practices or infrastructure (e.g. introduction of a global Unique Product Identifier (UPI) or Unique Transaction Identifier (UTI)) that would assist the aggregation process, and it recognises where relevant that the aggregation option chosen may have impacts on TRs, market participants, related data providers, authorities and other stakeholders. 2. Chapter 2 – Stocktake of Existing Trade Repositories 2.1 TR reporting implementation and current use of data As indicated in the FSB’s sixth progress report on the implementation of OTC derivatives market reforms, 3 22 TRs in 11 jurisdictions are, or have announced that they will be, operational.

It is not anticipated that TRs will be located in all jurisdictions but rather that regulatory frameworks will, in some instances, facilitate reporting of market participants’ transactions to foreign-domiciled TRs that are recognised, registered or licensed locally. At present, the practical availability of TRs is quite uneven among FSB member jurisdictions, with very few TRs authorised to operate in multiple jurisdictions and some jurisdictions requiring that domestic reporting be limited only to TRs run by domestic authorities or operators. In some jurisdictions, firms are only permitted to meet their reporting obligations 3 See FSB sixth progress report on implementation http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_130902b.pdf. 9 of OTC derivatives market reforms: .

by reporting to TRs that have been appropriately authorised (or alternatively granted an exemption from being authorised) in the jurisdiction in which the TR is offering services. In these jurisdictions, therefore, participants cannot meet their reporting obligations until relevant TRs have been authorised, recognised, or granted an exemption from a registration or licensing regime. In any given jurisdiction, the number of local TRs eligible for reporting ranges from zero to 11, and overseas TRs from zero to eight. The pace of implementation of TR reporting shows some differences across jurisdictions. In several jurisdictions there is some form of phased implementation, whether by asset classes or by market participant categories (largest financial participants/below threshold, regulated/end user).

By end-2014, a significant number of jurisdictions will have mandatory TR reporting in place for all asset classes. Other jurisdictions are either expected to have mandatory TR reporting in place by 2015 or have not yet set a date for all asset classes. The scope of implementation presents some differences. For instance, while financial institutions are subject to reporting in all jurisdictions, in some jurisdictions non-financial institutions may not be subject to mandatory reporting or some thresholds may be in place.

In some jurisdictions, transactions have to be conducted and booked locally in order to be subject to reporting, while in other jurisdictions transactions conducted locally but not booked locally or not conducted locally but booked locally are also subject to reporting. In some jurisdictions two-sided reporting is required while other jurisdictions have opted for one-sided reporting. In all but one jurisdiction, 4 reporting has to be made to TRs, with reporting to authorities being only a fall-back option when there is no TR in place. The time limit for reporting may also vary across jurisdictions from reporting on the same day, up to T+30, with most jurisdictions applying a reporting limit under T+3. In most jurisdictions where TR reporting requirements are in place, authorities typically have access to the data held in the TRs as consistent with their mandates. However in some jurisdictions, only a subset of authorities has regulatory access based on the current regulation in place.

In other jurisdictions, where TR reporting requirements are not yet in place, access is provided on a voluntary basis. These differences reflect the different pace of TR legislation implementation across jurisdictions. Authorities usually receive the data based on a specific format according to their respective mandate (with the format differing across authorities) while in some jurisdictions authorities have continuous online access to TRs. Most authorities have access to data based on several mandates (such as financial stability assessment, micro-prudential supervision, and market conduct surveillance). Even once reporting requirements are in place in all jurisdictions, no single authority or body will have a truly global view of the OTC derivatives market, even on an anonymised or aggregate-level basis, unless a global aggregation mechanism is developed. 4 In that jurisdiction, reporting to either the TR or authorities is allowed. 10 .

2.2 Available data fields and data gaps The review of data collected by TRs demonstrates that there are strong commonalities on data fields collected across jurisdictions for a number of key economic terms of contracts such as start dates, description of the payment streams of each counterparty, value, option information needed to model value, and execution information such as execution venue name and type. However, some differences in approach remain, including (but not limited to): • the main difference relates to the market value of transactions and collateral or margining information that are mandated for reporting in some jurisdictions, while they are not in other jurisdictions, • the distinction between standardised and bespoke contracts is reported only in one jurisdiction, • execution information is widely reported except the information on whether a trade is price-forming, which is collected only in a few jurisdictions, • clearing information is not widely reported with the name of the CCP being collected only in a few jurisdictions. In some jurisdictions, transactions once cleared must be reported as being modified transactions, while in other jurisdictions, the clearing results in the required reporting of both the termination of the initial transaction and the initiation of new ones. While transaction, product and legal entity identifiers are widely used, it seems that transaction and product identifiers may depend on different taxonomies which would require further details to ensure unicity (for transaction identifiers) and to check for consistency (for product identifiers) before aggregation. 2.3 Data standards and format The review of data standards and formats utilised by the different TRs in collection and storage of OTC derivatives data demonstrated different approaches that were chosen by various jurisdictions and TRs in addressing the G20 reporting requirement implementation. When it comes to the development and maintenance of reporting data standards, different jurisdictions follow different approaches. While a number of jurisdictions provide specific layouts of the fields and files, some do it for all OTC derivatives asset classes while others have different treatment for different asset class products. On the other extreme, a number of jurisdictions have not implemented data standards for TR data at all.

In some cases, jurisdictions have chosen this approach intentionally by relying on relevant internationally accepted communication procedures and standards, while in other cases standards and harmonisation work is being undertaken but is not yet complete. In this context, some jurisdictions suggest the use of an UPI approach as a uniform product data standard for OTC derivatives data reporting in their rules. However, there is currently no internationally accepted UPI standard.

Among jurisdictions that have prescribed standards, they mostly cover credit, currency, equity and interest rate OTC derivatives although the coverage varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Very few jurisdictions have developed data standards for commodity derivatives, particularly the identification of the underlier (and not only the derivative itself, for which the UPI may suffice). 11 . While some do standards development and maintenance on the regulatory level, others outsource that either to TRs or industry associations or similar body. Some authorities use a hybrid model of the above approaches. A number of authorities indicated that they use some proprietary data items such as Reference Entity Database (RED) Codes 5 in their reporting requirements. However, it was noted that the proprietary licensed data standards seem to be used only for reporting of credit derivatives. The application of tagging standards also varies significantly among jurisdictions yet, in general, only a minority of authorities decided to implement data tagging standards for the OTC derivatives reporting. 2.4 Legal and privacy issues As previously pointed out in the FSB progress reports on the implementation of OTC derivatives market reforms, some jurisdictions have privacy laws, blocking statues and other laws that might prevent firms from reporting counterparty information and foreign authorities from reaching the necessary data from TRs. Some of the jurisdictions will address the issues by changing/enacting new legislations, while others continue to work through possible solutions. In most jurisdictions, TRs are permitted to disclose confidential information only to entities that are specified in law or regulation, and generally these entities include only authorities.

In such cases, access to TR data may be provided to third country authorities only if certain conditions are met, including, for example, the conclusion of an international agreement or Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). In several jurisdictions, a local TR may directly transmit data only to national or local authorities. In some of these jurisdictions, foreign authorities may be granted indirect access to the data via national or local authorities, provided certain conditions are met, including, for example, MoUs between national/local and foreign authorities. 3. Chapter 3 – Authorities’ Requirements for Aggregated OTC Derivatives Data 3.1 3.1 Data Needs Both the Data Report and the Access Report broadly outline the potential data needs of authorities and provide guidance for minimum data reporting and access to TRs.

The Data Report also discusses the importance of legal entity identifiers and a product classification system and makes general recommendations on how to achieve adequate aggregation. The Access Report focuses on the access requirements of authorities under different mandates and the procedures that facilitate authorities’ access to TR data. In order to categorise the diverse needs of authorities for aggregated data across TRs, this feasibility study follows the functional approach employed in the Access Report. This approach maps data needs to individual mandates of an authority and their particular objective 5 Unique alphanumeric codes assigned to all reference entities and reference obligations, which are used to confirm trades on trade matching and clearing platforms. 12 .

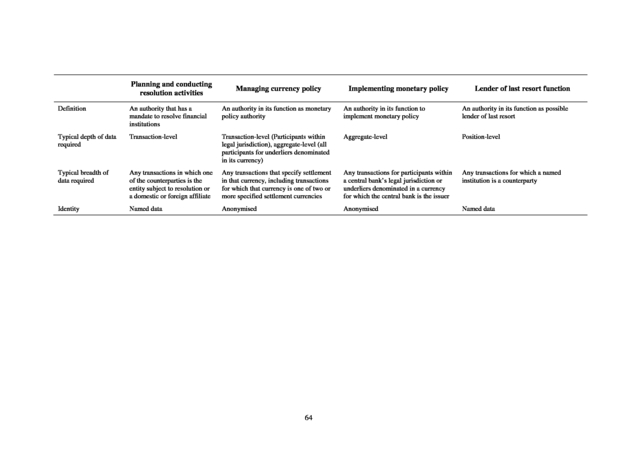

rather than to a type of authority. These mandates may evolve over time. They include (but are not limited to): • Assessing systemic risk, • Performing general macro assessments, • Conducting market surveillance and enforcement, • Supervising market participants, • Regulating, supervising or overseeing trading venues and financial market infrastructures (FMIs), • Planning and conducting resolution activities, • Implementing currency and monetary policy, and lender of last resort, • Conducting research to support the above functions. Appendix 3 describes these mandates as defined in the Access Report. Each mandate has different data needs. The mandates differ considerably in their requirements for data aggregation.

For example, authorities conducting market surveillance and enforcement generally need only data from market participants and infrastructures in their legal jurisdiction. They are frequently also supervisors of the TR where their market participants report, potentially giving them greater access and control of data. In contrast, other mandates would require access to a certain depth and breadth of data across participants and underliers which would not lend itself to a narrow jurisdictional view.

For instance, authorities who assess systemic risk or perform general macro assessments have the need, according to the Access Report, not only for data on counterparties within their jurisdiction but also for anonymised data on counterparties outside their jurisdiction. These data are needed to assess global vulnerabilities and spill-overs between markets. Obtaining these data in a usable format requires the collection of data from many trade repositories in a consistent format with duplicates removed and identifying information masked, as described below.

It also requires the creation of aggregate-level data on exposures. Prudential supervisors similarly need data going beyond their market in order to assess the exposures of firms at a globally consolidated level. 6 For these mandates, a global aggregation solution is essential for providing adequate transparency to the official sector concerning the OTC derivatives market.

Currently, no authority has a complete overview of the risks in OTC derivatives markets or is able to examine the global network of OTC derivatives transactions in depth. The complex set of needs of various authorities calls for an aggregation mechanism providing flexibility and fitted for evolutionary requests as financial markets and products evolve. It is also equally important for such a mechanism to be evolutionary in nature in order to respond 6 Prudential supervisors would need the following aggregated data to assess the soundness of entities operating in multiple jurisdictions: Counterparty exposures to assess the counterparty credit risk; Data on net position, valuation and collateral to assess the market risk of each portfolio of OTC derivative instruments; Data on periodic contractual cash flows in OTC derivatives to be used for assessing overall liquidity risk of the entity. 13 . to evolving needs for aggregated data by authorities. It appears that a key factor differentiating these aggregated data relates to whether they refer to named data or not. To provide authorities with the aggregated data consistent with the Access Report, various types of data aggregation will be necessary to complement the data that authorities may directly access from TRs. Some of the most important processes that are essential for aggregating TR data are described in the following sections. 3.2 Aggregation Minimum Prerequisites The following steps are core to any aggregation of OTC derivatives data for all types of mandates. These steps would apply regardless of the aggregation model used.

Box 1 illustrates the various aggregation steps through some example uses of TR data by authorities with particular mandates. Chapter 5 further expands on technical implementation of these steps. a) User Requirements for Data Harmonisation TR data originate from a wide range of market participants submitting data in a variety of formats over numerous communications channels. TRs themselves have different interpretations of terminologies, reporting specifications and data formats depending on the rules in their jurisdictions and their own choices.

TR data must therefore be transformed into a common and consistent form for use in analysis on an aggregated level. This would be easier if the same interpretations and data standards are implemented across TRs. Where data standards and interpretations are different, harmonising the data is more difficult and perhaps in some cases impossible. Some important examples of necessary harmonisation are: • Need for a consistent interpretation of terminologies (e.g., transaction, position, UPI, whether the quantity of a transaction or of a position is expressed in the number of contracts or their value, etc.), • The standard and format for expressing the terms of a transaction (such as the transaction price, quantity, relevant dates, and terms specific to certain types of securities such as rates, coupons, haircuts, value of the underlying, etc.) and whether a transaction is a price-forming trade, • The identification of trades that are submitted for clearing and the child-trades created as a result.

In some jurisdictions transactions once cleared must be reported as being modified transactions, while in other jurisdictions, the clearing results in the required reporting of both the termination of the initial transaction and the initiation of the new ones (“alpha-beta-trade” issue). b) User Requirements for Concatenation Data necessary for fulfilling authorities’ mandates may be held in several individual TRs in different locations. This is the result of competitive forces as well as regulatory requirements in various jurisdictions. Data are, therefore, physically and logically fragmented.

The current landscape is described in Chapter 2. In order to analyse data, each authority will need, directly or indirectly, legal access and technical connections to each TR containing relevant data. Certain analyses can be 14 . accomplished with partially fragmented data sets. For example, the mandates “Registering and regulating market participants” and “Supervising market participants with respect to business conduct and compliance with regulatory requirements” can be accomplished with data only from the (potentially small) number of TRs where specific market participants report. In contrast, the mandate “Assessing systemic risk” requires data from essentially all TRs and therefore needs a great deal of concatenation. One challenge is how an authority can know which TR holds data relevant to its mandate, given the proliferation of TRs and the various reporting requirements in different jurisdictions. c) User Requirements for Data Cleaning In the numerous stages of data reporting and processing 7 from the origin of the trade, submission to the TR, aggregation, and up to the analysis by the authority, errors could be introduced in the data.

While TRs are required to produce clean data, it might still be necessary for the data to be checked for errors and corrected wherever possible before the aggregation mechanism is capable of delivering meaningful results. d) User Requirements for Removal of Duplicates An important issue inherent in OTC derivatives data is the problem of duplicate transaction records, or “double counting”. Duplicate records could potentially be collected and stored in several TRs. Duplicates might result from the concatenation of data from different TRs. Each party to a given contract might report the event (any “flow event” such as a new trade, an amendment, assignment, etc.) to two (or more) different TRs in the same or different jurisdictions.

For example, Party A might report an event to a TR located in jurisdiction A and Party B might report the same event to a TR located in jurisdiction B. If data from the TR A and the TR B are combined into a single dataset, a record for this single event will appear in the dataset twice. This double-reporting may have been done to comply with local regulations; alternatively, it may have resulted from voluntary reporting practices. For instance, when a transaction is made on an electronic trading venue with an associated TR, the transaction might automatically flow into the venue’s TR, but the counterparty might also choose to report it to another TR so that it can gain a comprehensive view of its transactions through that utility. It is challenging to eliminate duplicate transactions particularly when combining two different datasets, and even more so in the absence of data harmonisation and standardisation.

If the two datasets are simply concatenated, the combined dataset would include duplicate transactions and any measures of exposure or other sums would be biased. If a global system of UTIs were in place, these could be used to match and eliminate the duplicates. If there is no effective UTI, the authority then has the following options: • 7 If the dataset is named or partially anonymised, the analyst (or aggregation mechanism in Options 1 and 2) could develop an approach to eliminate likely duplicates assuming some accepted degree of error (for example, the user could Processing refers to all steps incurred by data along the trade lifecycle, including the amendments to the contract, that in some jurisdictions have to be reported to the TR and thus increase the probability of errors to be introduced in the data. 15 .

define duplicate events as those with the same counterparties, same contract terms, and same transaction date and times). • If the dataset is fully anonymised, i.e., no counterparty information is provided, there is no solution to remove the duplicates. e) User Requirements for Anonymisation Under certain mandates, authorities only have rights to obtain anonymised data and may be legally prevented from obtaining named data. Other mandates additionally necessarily require access to named data, at least for participants and/or underliers located in their respective jurisdictions. There are two ways to anonymise named transaction data: • Records can be fully anonymised, where the counterparty name or public identifier (such as Legal Entity Identifier (LEI)) is redacted. This type of anonymisation is simple and can be performed on different datasets of raw transaction events prior to concatenation.

For example, TR A and TR B can themselves remove counterparty names from their respective datasets before sending to a user third party to combine. It has to be highlighted that once raw transaction event data are fully anonymised, the derivation of position data or other summing by counterparty is not possible. Also it has to be emphasised that, as mentioned above, removing duplicates from fully anonymised data would be impossible. In particular, full anonymisation implies also the removal of UTIs from the data because they are based on codes that identify participants. • Alternatively, records can be partially anonymised, or masked, where counterparties are given unique identifiers that are used consistently across the entire dataset.

For example, TR A could assign the identifier “1234” to Market Participant X and “5678” to Market Participant Y. Partial anonymisation could be performed by a single party, i.e., the aggregation mechanism, to perform the masking on a given dataset. In this case, if TR B assigns the identifier “ABCD” to Market Participant X, a user third party could not know it is the same entity as “1234”.

Partial anonymisation could also be performed locally in TRs, based on a set of agreed-upon and consistent anonymisation rules and translation data. Partial anonymisation allows a user to construct positions or otherwise sum up raw events by unique counterparty, without knowing the actual identity of that counterparty. This is crucial for many types of network and systemic analysis as well as for netting gross bilateral positions. While partial anonymisation is an appropriate step for providing authorities with some needed aggregated data, it remains that some mandates additionally necessarily require named aggregated data. The above approaches are possible assuming that the dataset is comprised of raw transaction event data.

If transaction flow events are summed up into positions or otherwise aggregated, it is impossible to eliminate double counting because the building blocks going into each position calculation are not known. f) User Requirements for Providing Timely Data Authorities have a need for both regular requests and ad hoc requests. Routine requests would typically come at daily, monthly or quarterly intervals (or other pre-defined regular intervals). In some cases, rapid responses to ad hoc requests will be essential, in particular under stress 16 . conditions. In general, the data should be available within a short time lag. While in some cases almost real time data is necessary, a timeliness of up to three business days (T+3), which happens to be the maximal time lag for reporting in almost all jurisdictions, would be enough for most of the mandates. Because some jurisdictions do not require real-time reporting, aggregation exercises that require data from those jurisdictions can only be done at an appropriate delay after the event. Attempting aggregation earlier would lead to incorrect results. 3.3 Further aggregation requirements The following steps would be needed for certain types of analysis but are not essential for all mandates. a) User Requirements for Calculation of Positions Several mandates require information on the positions of market participants: the sum of the open transactions for a particular product and participant at a particular point in time. This will require tools to identify the transactions to be summed.

In particular: • The participant identifiers (LEI) are required to accumulate accurate position data across TRs. The LEI with hierarchy (for consolidation purpose) is also needed for some mandates at least in a second step when the fully fledged LEI is in place. • Product identifiers (ideally UPIs, and any other instrument identifier available) are needed to do accurate product-level analysis. Different analyses require different levels of product identification granularity. • ID of underlying (e.g.

reference entity identifier, reference obligation and restructuring information in case of credit derivatives, reference entity identifier for equity derivatives, benchmark rate in the case of interest rate swaps and cross currency swaps) are required to conduct various analyses (for instance, to measure total exposure in a given reference entity, or to value the trades for any analyses where market values, rather than notional amounts, are aggregated and where the TR does not collect those market values). b) User Requirements for Calculation of Exposures The current exposure of a derivative portfolio — defined as the cost of replacing the portfolio in current market conditions net of any collateral backing it — is an important measure of risk that is of interest to authorities. Calculating exposures requires not only position data, but also data on valuations, collateral (e.g., amount and composition of applied collateral) and netting sets. Such information includes external bilateral portfolios between pairs of market participants and portfolios of centrally cleared transactions (particularly important for including collateral information).

An ID of collateral pool and netting set would be necessary to connect multiple trades to their common collateral pool and netting sets. This data will not be available in all TRs due to differences in regulatory requirements. Any aggregation solution should, however, take into account the requirements to calculate exposures where possible and to incorporate more complete data in the future.

There is also a need for authorities to be able to calculate exposures combining aggregated OTC derivatives data with data on exchange-traded products or cash instruments (bonds, equities, etc.). 17 . Box 1: Illustrations of data aggregation requirements This box illustrates the various aggregation requirements described above through some example of data uses of by authorities with particular mandates. Other uses by authorities with different mandates frequently encounter several of these issues. Business conduct supervision. The first example relates to an authority with a mandate for supervising participants with respect to business conduct (see Annex 4 for data such an authority may have access to). This regulator suspects that a bank in its jurisdiction has traded on private information obtained during a loan renegotiation with a debtor by buying credit default swaps (CDS) that offer protection against potential losses due to the default of that debtor.

Hence, the regulator wants to know the net amount of credit protection on the debtor bought by the bank over the past few days. An aggregation mechanism would allow the authority to have a broader picture in order to detect violations. As the relevant CDS transaction event records may reside in a number of different TRs, they must first be brought together. Essentially these transaction records must be extracted from their respective TRs and concatenated.

This could be done easily if each TR used the same data fields (with the same meaning/interpretation) and formats. Two particularly important data fields in this application are those containing the identities of the bank counterparty and the debtor referenced in the CDS contracts. These could be accurately searched if all TRs used the universal set of unique LEIs.

8 As transaction events may have been reported to more than one TR, the regulator would want any duplicate records to be eliminated. If all TRs applied a UTI for each of the trades that they store, this could be done simply by eliminating any records from across TRs with duplicate UTIs. Armed with a comprehensive and comparable list of duplicate-free transaction event records, the regulator could finally compute the net credit protection bought by the bank on its debtor over the past few days. It should do this by summing purchases of credit protection and subtracting any sales of credit protection.

Only ‘price-forming’ trades should be included in this calculation. 9 Calculating positions. A second example of data uses illustrates the aggregation requirement of calculating positions.

It concerns a central bank with a financial stability mandate with a need to check whether any systemically-important firms in its jurisdiction have large OTC derivatives positions. Suppose that such authority wanted to know the size of CDS positions referencing a particular country’s sovereign debt sold by Bank A (including all its subsidiaries), located in its jurisdiction. The transaction records that comprise this position potentially reside in a number of different TRs, so the authority would need the relevant trade records to be extracted and concatenated as in the first example. In this case, relevant contracts are any that end up with Bank A as the protection seller.

This includes all contracts originally sold by Bank A but which have not yet matured or otherwise terminated. It also includes any contracts that 8 In addition, if the regulator asked authorities in other jurisdictions to search for any trades conducted by legal affiliates of the bank, it would be a simple matter to find their LEIs given the LEI of the bank once the hierarchy is in place within the LEI system. 9 Non-price-forming trades, such as those arising from compression cycles and central clearing, would not affect the bank’s positions against the potential default of the debtor. They only affect the counterparties to these positions. 18 .

were reassigned from the original seller of protection to Bank A. In both of these cases, the latest information about the trade contract would be needed, so any partial terminations or notional amount increases would also have to be extracted from the TR. After harmonising data standards and removing any duplicate transaction records, again as in the first example, the position of Bank A referencing that country’s sovereign debt could finally be computed as the sum of outstanding transaction event records. Expanding this second example brings in the aggregation requirement of anonymisation. Say the authority learned that Bank A had sold a large volume of credit protection on the sovereign debt of the country mentioned above. It might then want to know the overall degree to which market participants relied on Bank A for the supply of this insurance. Simple measures of market share require a comparison of the volume of protection sold by the bank with the overall level of protection sold by all market participants.

More advanced statistical measures of network centrality take into account not only that many counterparties might rely directly on Bank A for credit protection, but that others might rely indirectly on Bank A having bought protection from a counterparty that in turn bought protection from Bank A. Computation of such measures requires data on all such links between counterparties as summarised in a matrix of bilateral positions, but the names of the protection buyers and sellers (other than Bank A) are not important. Hence, the names of these market participants could be partially anonymised before centrality is calculated. Calculating exposures.

Finally, further expanding this example illustrates the aggregation requirement of calculating exposures. Say the authority was concerned about the solvency of a financial institution in its jurisdiction and, given the centrality of Bank A as a seller of an important type of credit protection, wanted to know if Bank A was exposed to this institution through OTC derivatives. Computation of this exposure first requires data on all outstanding positions across various OTC derivative asset classes between Bank A and the institution of concern (i.e.

named data is required). As in the first example, the positions can be calculated, after data harmonisation and removing duplicates, by summing all open transaction between Bank A and the other entity. Then it requires these positions to be valued.

Some TRs will collect this valuation information, but others will not. Where it is not collected, derivatives positions may be valued using the prices of their underlying assets, which may be taken from a third-party database. This could be facilitated by the use both by TRs and third-party price providers of standard codes to identify underlying assets. In principle, any collateral posted against the market value of a bilateral derivatives portfolio should then be deducted from that market value to determine the exposure. However, not all TRs will collect this information and third-party sources of collateral data are much less readily available than for price data. 4. Chapter 4 – Legal Considerations TRs are mostly regulated at the national level by national laws, and TRs that operate on a cross-border basis may be subject to more than one regulatory regime.

10 10 The TR may be regulated in a jurisdiction other than its home jurisdiction, due to being registered, licensed or otherwise recognised or authorised in that jurisdiction, or conditionally exempt from registration requirements in that jurisdiction. 19 . Rules applicable to TRs usually concern the fields and formats for the information being reported (mandatory reporting), information being accessed (regulatory access) and organisational requirements. TRs are also usually subject to professional secrecy requirements, including relevant confidentiality/privacy/data protection laws. The feasibility of Options 1, 2 and 3 in the current legal environment depends on the compatibility of the steps needed to implement these different options with the existing rules applicable to TRs. Legal challenges in implementing the different options stem from different levels of applicable law within a jurisdiction (e.g. sectoral legislation and/or confidentiality law of general application) as well as from cross-border issues. This chapter analyses the legal considerations associated with the feasibility of the aggregation options described in Chapter 1 following three main dimensions: (i) the submission of the data to the global aggregation mechanism, (ii) access to the global aggregation mechanism, and (iii) the governance of the global aggregation mechanism.

For each component, the chapter presents legal considerations associated with the implementation of each option. The analysis focuses on the jurisdictions where TRs are established/registered/licensed 11, or will be in the short term, and pertains to the legal considerations applicable to data reported to TRs on a mandatory basis. 12 Last but not least, the analysis focuses on the feasibility of aggregating data held in TRs that are not “personal data” (i.e., data on natural persons 13). In the exceptional cases where personal data are stored in TRs, this study assumes that personal data would not be included in the aggregation mechanism because it would likely not be needed in order to satisfy authorities’ data requirements. Besides the reference material mentioned in Chapter 1, the analysis of this chapter has also been informed by the FSB fifth and sixth progress reports on the implementation of OTC derivatives reforms 14 which include descriptions of confidentiality issues related to the reporting of OTC derivatives into TRs.

The analysis also builds upon the discussion of the International Data Hub relating to global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) and the LEI global initiative. 11 Appendix D of the FSB’s sixth progress report on implementation of OTC derivatives reforms provides a list of TRs operating or expected to operate as of August 2013. The list of jurisdictions includes: Brazil, Canada, European Union, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Russia, Singapore and the United States. 12 There are two kinds of data reporting: mandatory reporting and voluntary reporting. The former is required by legislations and regulations, while the latter is reported without such requirements.

The ability to share data reported to TRs on a voluntary basis raises different legal issues which are out of scope of this study. 13 Personal data could be data about natural person counterparty to the trade, or data about a natural person that arranged the trade on behalf of counterparty. 14 http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_130415.pdf http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_130902b.pdf 20 . 4.1 Types of existing legal obstacles to submit/collect data from local trade repositories into an aggregation mechanism 4.1.1 Legal requirements applying specifically to the TR seeking to transmit data to the aggregation mechanism and regulating its capacity to share data In the existing regulatory environment, a TR seeking to transmit information to an aggregation mechanism – either to a physically centralised aggregation mechanism (Option 1) or a federated aggregation mechanism (Option 2) may face legal obstacles in its home jurisdiction, or in other jurisdictions in which the TR is regulated. In most jurisdictions legal requirements applying to TRs include limitations on the types of entities with which the TR may share data. These legal requirements may prevent local TRs from transmitting confidential information to an aggregation mechanism, depending on which entity operates the central aggregator, and which authorities have access to the aggregation mechanism. In several jurisdictions, TRs may transmit data only to national authorities, which would prevent the local TR from submitting data directly to an aggregation mechanism located outside the home jurisdiction. 15 In other jurisdictions, a local TR may share data with specified entities, or with entities of a specified kind (e.g., public entities such as authorities or regulators, and not private entities). In most jurisdictions, TRs are not permitted to disclose any confidential information to any person or entity other than authorities expressly authorised.

In some jurisdictions, the list of entities with access to TR data is defined by law 16. In others, the TRs’ supervisors may be authorised to designate the third-country entities entitled to access data held in local TRs. 17 In this context, the implementation of Option 1 and Option 2 (other than temporary local caching where necessary in the aggregation process), would require explicitly prescribing the aggregation mechanism (by law or by regulation) among the entities entitled to accessing local TR data.

This approach would require amending existing laws and/or regulation in several jurisdictions. In some jurisdictions, legal requirements include limitations on the purposes for which the local TR may share data with each type of entity. For example, some laws may restrict a local TR from sharing data with an entity that is a prudential regulator unless the data is required by the regulator for prudential supervision purposes. Unless it is possible under current law or regulation to designate or to include the aggregation mechanism as an entity entitled to access the data to the extent that the aggregation mechanism is fulfilling its mandate, TRs in such jurisdictions would not be allowed to share confidential information with the aggregation mechanism absent a change in law or regulation. Under Options 1 and 2, if the transmission of data from the individual TRs to the aggregation mechanism is performed on a routine basis, the TR may not know at the point of transmission which authorities will seek to access the data or for what purposes, and the TR therefore could 15 Brazil, India, Russia, Turkey 16 European Union 17 United States 21 .

not directly apply any access controls at its end. Where TRs are legally required to control access, they would be reliant on the aggregation mechanism to do so on their behalf. This outsourcing of controls might not be allowed in some jurisdictions without a change in law or regulation. If so, the issue would have to be addressed by the governance framework establishing the aggregation mechanism and regulating its access.

The governance issue including access rules is further discussed in Section 4.3. 4.1.2 Legal requirements of general application Privacy law, blocking statute and other laws A local TR may also be subject to legal requirements of general application such as privacy laws, data protection laws, blocking/secrecy laws and confidentiality requirements in the relevant jurisdiction, which are applicable to all the options. These legal requirements may prevent the TR from transmitting certain types of information to an aggregation mechanism under Options 1 and 2 absent a change in law or regulation. The legal requirements of general application that may prevent a TR or authority from transmitting data to the aggregation mechanism under Options 1 and 2, and may in some cases mirror obstacles that prevent participants from submitting data to a TR in the first instance. Those obstacles are discussed in the FSB’s fifth and sixth progress reports on OTC derivatives market reform implementation 18.

For example: • privacy laws may (subject to exceptions) prevent a TR from transmitting counterparty information to the central database (wherever located) where that information identifies a natural person or entity; • blocking/secrecy laws may (subject to exceptions) prevent a TR from transmitting/disclosing information relating to entities within a particular jurisdiction, to third parties outside that jurisdiction and/or foreign governments. In some jurisdictions, the TR may be able to rely on exceptions to privacy laws expressly listed in the laws or where there is a counterparty’s express written consent to the disclosure of the data. However, the requirements for consent differ across jurisdictions. In certain jurisdictions, one-time counterparty consent to disclosure to a TR is sufficient, while in others counterparty consent may be required on a per-transaction basis Consequences of breach As noted, the source of the above legal requirements may be laws, regulations or rules of the jurisdiction in which the TR is located, or of another jurisdiction in which the TR is regulated. Other sources of these requirements may be conditions of the TR’s registration, licensing or other authorisation in a particular jurisdiction, or contractual arrangements to which the TR is a party, including the TR’s own rules and procedures.

These conditions or contractual arrangements may be designed to support compliance with local laws, e.g., privacy laws. A TR that breaches these legal requirements may be exposed to civil liability or criminal sanctions in the relevant jurisdiction. Further, if a TR is required to ensure that the entity that operates the aggregation mechanism, or authorities that have access to the aggregation 18 See section 3.2.1. http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_130415.pdf http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_130902b.pdf. 22 and 6.3.1 of . mechanism comply with specified requirements (e.g. undertakings as to confidentiality) with respect to the data transmitted, the TR may be exposed to liability if the aggregation mechanism or authority breaches those requirements. These potential obstacles could limit the capacity of the TR to transmit confidential data to the aggregation mechanism, and could therefore limit the range of data held in the aggregation mechanism, which might prevent authorities from accessing all the information they need in carrying out their regulatory mandates. Factors mitigating the legal obstacles to transmission of data by TRs • Type of data being transferred: anonymised and aggregate-level data. The legal obstacles may differ depending on the type of data being transferred to the aggregation mechanism under Options 1 and 2. Sending aggregate-level data or data in anonymised 19 form could mitigate most of the confidentiality issues identified above which apply to the transmission of confidential data. On the other hand, it should be noted that transmission of data that has already been anonymised (e.g., with no LEI or other partyrelated information) or that has already been summed faces serious drawbacks, such as the inability to eliminate double-counting and the inability to perform calculations of positions or exposures as discussed in Chapter 3. • Authorities acting as intermediaries for the transmission of data into the database. Transmitting data from local TRs to the aggregation mechanism via authorities may alleviate some of the legal concerns identified above, since most authorities have, unlike TRs, the capacity to share confidential information with other authorities, provided certain conditions are fulfilled, notably within existing frameworks of cooperation arrangements for data sharing. 4.2 Legal challenges to access to TR data In a few jurisdictions, direct access by foreign authorities to data held in local TRs is not permitted.

However, in some jurisdictions 20, foreign authorities may be granted indirect access to the data via national authorities – usually the supervisor of the local TR (or after approval of the supervisor) – provided MoUs have been concluded. In most jurisdictions, regulatory access to TR data is provided by law and includes access by third country authorities, provided certain conditions are met. These conditions may include the conclusion of MoUs - or specific types of international agreements 21 - between relevant authorities on data sharing. 19 A methodology to do so would need to be further defined and demonstrated. Different types of anonymisation are described in Chapter 3.

The methodology would need to address the issue that, in some circumstances, anonymised counterparty identities may be ascertainable e.g. based on historical trading patterns or account profiles, or because of lack of depth in the market. 20 Brazil, Russia, and Turkey 21 For example, in the EU, as a condition for direct access to EU-regulated TR data by third country authorities from jurisdictions where TRs are established, the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR) requires that international agreements and co-operation arrangements that meet the requirements of EMIR be in place between the third country and the EU. For third country authorities from jurisdictions where no TR is established, EMIR requires the conclusion of cooperation arrangements. 23 .

In some jurisdictions, pre-conditions to access by certain authorities have to be met. For example, a TR may be required to take specified steps before sharing information with an entity, such as ensuring that an agreement or undertaking as to confidentiality, or indemnification 22 in respect of potential litigation, is in place with the requesting entity. Under Options 1 and 2, authorities would access global OTC derivatives data via the aggregation mechanism. New rules specifying who may access the data, the coverage of the information that may be accessed, and the conditions for access would therefore need to be globally agreed as developed in the governance section below. These rules and conditions for access would need to reflect any legal conditions under which the data was transmitted to the aggregation mechanism.

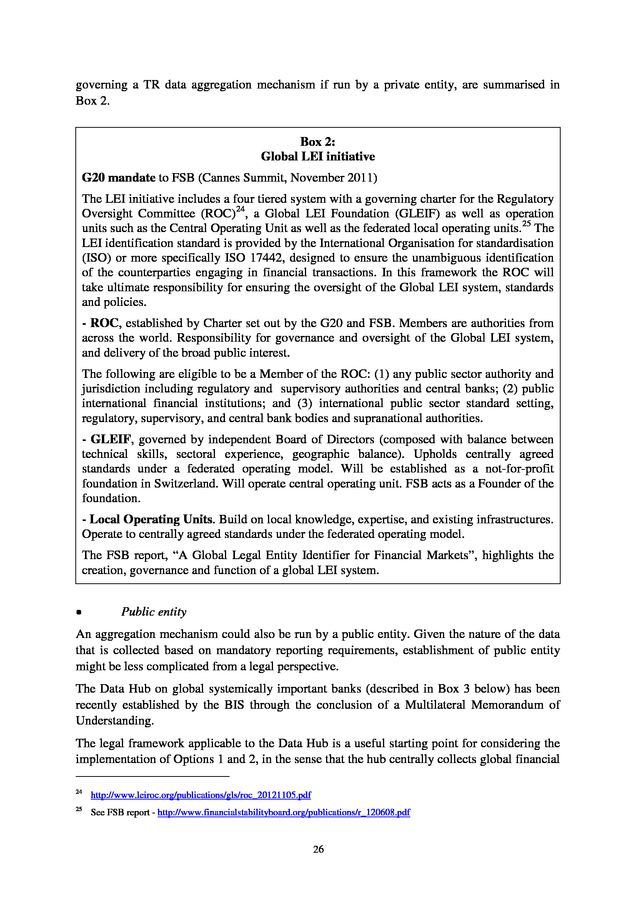

This new international framework may solve the existing access issues above to some extent in a sense that this framework can be a substitute for bilateral MoUs. 23 Under Option 3, authorities would access information directly at local TRs. Option 3 would depend on the completion of the additional steps required under the existing regulatory frameworks to permit access to local TRs by worldwide authorities or would require changes in the existing regulatory frameworks. 4.3 Legal considerations for the governance of the system 4.3.1 General analysis The objective of this section is to analyse the legal considerations related to the governance of the aggregation mechanism for each option proposed, analysing what would likely need to be defined and agreed internationally to ensure the global aggregation mechanism could be implemented and managed. Under Option 1, a physically centralised aggregation mechanism would be established to collect and store data from local TRs.

This aggregation mechanism would subsequently aggregate the information and provide it to relevant authorities as needed. Some changes to the existing regulatory frameworks would be required to set up an aggregation mechanism entitled to collect confidential information stored in local TRs. Option 2 would not physically collect or store data from TRs in advance of a data request, instead it would rely on a central logical catalogue/index to identify the location of data resident in the TRs. In this model, the underlying data would remain in local TR databases and be aggregated via logical centralisation by the aggregation mechanism, being retrieved on an “as needed” basis at the time the aggregation program is run. Options 1 and 2 require a global framework to be defined specifying (i) which entity would operate the aggregation mechanism, (ii) how the aggregation mechanism would be managed and overseen/supervised, (iii) access rules (which authorities would have access to which information according to their mandate and confidentiality restrictions in the use of data). 22 For example, in the US, the Dodd-Frank Act requires that, as a condition for obtaining data directly from a TR, domestic and foreign authorities agree in writing to indemnify a US-registered TR, and the SEC and CFTC, as applicable, for any expenses arising from litigation relating to the data provided.