Description

International Environmental and

Resources Law Committee Newsletter

Vol. 18, No. 2

March 2016

A joint newsletter of the International Environmental and Resources Law Committee,

Marine Resources Committee, and the

Section of International Law’s International Environmental Law Committee

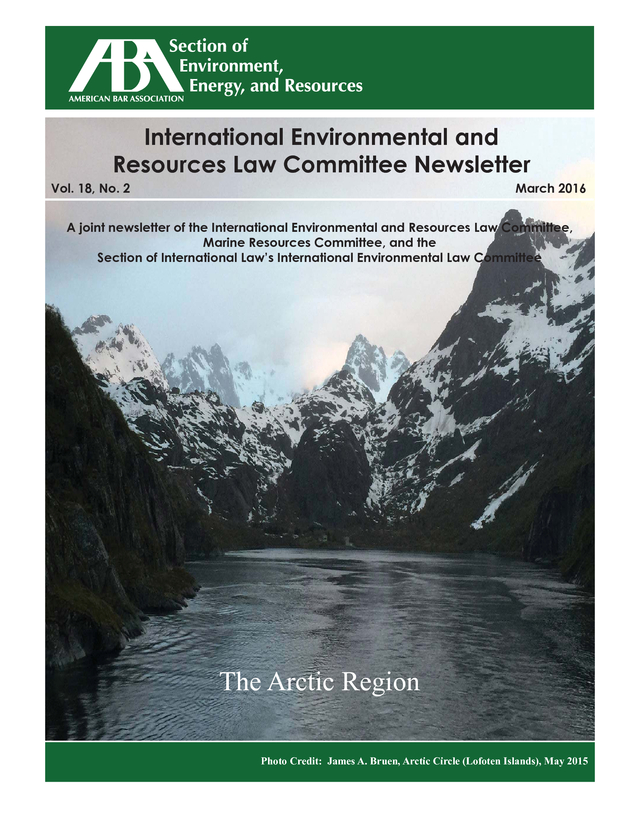

The Arctic Region

Photo Credit: James A. Bruen, Arctic Circle (Lofoten Islands), May 2015

International Environmental and Resources Law Committee, March 2016

1

.

International Environmental and Resources Law Committee Newsletter Vol. 18, No. 2, March 2016 Shannon Dilley and Jonathan Nwagbaraocha, Editors AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION SECTION OF ENVIRONMENT, ENERGY, AND RESOURCES CALENDAR OF SECTION EVENTS CALENDAR OF SECTION EVENTS In this issue: Chair Message Stephanie Altman, R. Juge Gregg, Niki L.

Pace, Fatima Maria Ahmad, and Anastasia Telesetsky .............................3 Polar Opposites: Should Arctic Environmental Governance Follow the Antarctic Model? Mark P. Nevitt and Robert V. Percival ..................................4 Under the Ice: Arctic Nations Seek to Curb Commercial Fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean Fred Turner ..............................................9 The U.S.

Imperative for New Icebreakers Joan M. Bondareff and James B. Ellis..........................................13 Fulï¬lling Tribal Trust and Arctic Responsibilities: U.S.

Co-Management of Marine Resources Kathryn Mengerink, Greta Swanson, and David Roche ........................................17 A Canadian Perspective on Key Arctic Issues: Governance, Resource Development, and Navigation Tony Crossman and Nardia Chernawsky .............................21 A Royal Dutch Pain: Summary of the Challenges and Regulatory Gaps in Arctic Offshore Drilling Jonathon D. Green ..............................24 March 29-30, 2016 34th Water Law Conference Austin, TX March 30-April 1, 2016 45th Spring Conference Austin, TX April 12-16, 2016 SIL Spring 2016 Meeting New York, NY June 14, 2016 Key Environmental Issues in U.S. EPA Region 5 Conference Chicago, IL October 18-22, 2016 SIL Fall 2016 Meeting Tokyo, Japan For full details, please visit www.ambar.org/EnvironCalendar Copyright © 2016.

American Bar Association. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Send requests to Manager, Copyrights and Licensing, at the ABA, by way of www.americanbar.org/reprint. Any opinions expressed are those of the contributors and shall not be construed to represent the policies of the American Bar Association or the Section of Environment, Energy, and Resources. 2 International Environmental and Resources Law Committee, March 2016 .

THE U.S. IMPERATIVE FOR NEW ICEBREAKERS Joan M. Bondareff and James B. Ellis Executive Summary The U.S.

Coast Guard, under new guidance from President Barack Obama, is moving forward to acquire one new polar icebreaker for the United States. However, the United States, as a leading maritime power and Arctic nation, needs more icebreakers and has yet to determine how to fund these very expensive ships. This article describes the United States’ disappointing history with polar icebreakers and why they are badly needed. Background The U.S.

Coast Guard is the primary maritime law enforcement agency of the United States. This role includes search and rescue, especially in the Arctic where the Coast Guard provides ships for other government agencies that have no capabilities in ice-covered areas. The Coast Guard also provides support to the U.S.

research station in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. As early as the 1800s, the Coast Guard and its predecessor, the Revenue Cutter Service, operated vessels with ice-breaking capabilities. As recently as the mid-1970s, the Coast Guard had five heavy polar icebreakers in its fleet. In 1976, the Coast Guard added two new heavy icebreakers—the Polar Sea and the Polar Star.

However, by 1990, they were the only remaining polar icebreakers in the fleet. In 2000, the Healy, a third, medium icebreaker was added. The Polar Sea and the Polar Star are approaching 40 years of service, and the Polar Sea is no longer operational, leaving the nation with only one heavy and one medium icebreaker.

At the same time, the U.S. role in the Arctic has expanded due to the melting icecap, opening of new shipping lanes, and expanded tourism from cruise ships in the Arctic. Yet the United States lacks the capacity to fully monitor these activities and conduct any needed search and rescue operations.

There is no viable plan for how to address the replacement of these aging vessels, much less how to bridge the five- to ten-year gap before a new icebreaker can be designed, built, and placed in operation. Congressional Interest in New Icebreakers For some, it is unthinkable that a great maritime power such as the United States would lack sufficient icebreakers to ply the frozen waters of the Arctic and the Antarctic and protect its national interests. This is in contrast to Russia whose icebreaker fleet numbers more than 40 and has 11 more in production. Ronald O’Rourke, Coast Guard Polar Icebreaker Modernization: Background and Issues for Congress, CONG. RESEARCH SERV., RL34391, at 11 (Jan.

15, 2016). Over the past two decades, various federal agencies, congressional committees, and academic and nonprofit institutions have completed a number of reports that recognized the need for a long-term plan to ensure that there were adequate icebreaking vessels available to carry out activities in the polar regions that were important to U.S. national interests, but no real action has been taken to address this growing crisis. The cost of building a new heavy icebreaker is estimated to be on the order of one billion dollars—a figure that, to date, neither the executive branch nor Congress has been willing to fund. We as a nation now find ourselves on the precipice of a major crisis in how to provide the resources necessary to protect our national interest in the Arctic.

There are, however, glimmers of hope for congressional support for the acquisition of at least one new icebreaker. Senator Murkowski from Alaska has intimated her support for funding the new icebreaker. This article argues for the need for the United States to build two or more icebreakers, to have them built in U.S. shipyards, and to have them acquired through incremental payments over a five- to ten-year period with contributions from other related federal agencies (e.g., the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the U.S.

Navy). International Environmental and Resources Law Committee, March 2016 13 . Why U.S. Icebreakers? The United States is not only a maritime nation, but also an Arctic nation. Despite this, the United States had not placed a high priority on pursuing its national interest in the Arctic. Only in the last few years as climate change, potential energy development in the region, and a high level of activity by Russia in the region, has the United States begun to focus more intensely on our national interests in the Arctic.

In fact, the United States is currently chairing the eight-member Arctic Council. The Obama administration developed a strategic plan for the Arctic in 2013, and in 2014, it developed an implementation plan for the Arctic. The White House, Implementation Plan for the National Strategy for the Arctic Region (Jan. 2014), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/ default/files/docs/implementation_plan_for_the_ national_strategy_for_the_arctic_region_-_fi.... pdf. The Alaska Arctic Policy Commission, in 2015, issued a report stating that “[t]he Arctic is an integral part of Alaska’s Identity.” Alaska Arctic Policy Commission, Final Report and Implementation Plan, Executive Summary, 2 (Jan.

30, 2015), available at http://www.akarctic. com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/AAPC_Exec_ Summary_lowres.pdf. The administration’s heightened commitment to the Arctic was highlighted further during President Obama’s trip to Alaska in the fall of 2015. At this writing, we are waiting to see if his FY2017 budget request reflects this commitment. The United States has a vast Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) that extends around the coasts of the United States and its territories seaward to 200 nautical miles, and it also has an extended continental shelf under the sea adjacent to the Alaskan coast that could extend more than 600 nautical miles under the boundary principles recognized by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

The United States recognizes these maritime principles as part of customary international law even though it has not ratified UNCLOS. See Ronald Reagan, 14 Proclamation 5030—Exclusive Economic Zone of the United States of America, American Presidency Project (Mar. 10, 1983), http://www.presidency. ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=41037. Russia has filed and amended a formal claim for an extended continental shelf with the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS).

See United Nations, Ocean & Law of the Sea, Commission on the Limits of the Continental shelf (CLCS) Outer Limits of the Continental Shelf Beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Baselines: Submissions to the Commission: Submission by the Russian Federation, http://www.un.org/Depts/los/ clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_rus.htm (last visited Jan. 30, 2016). This contrasts with the United States, which is still collecting data on the outer limits of its continental shelf and has not yet made a formal claim with the CLCS.

The United States is also hampered from protecting its claim because it is not an official member of CLCS due to its failure to ratify UNCLOS. Although the frozen Arctic landscape is less frozen these days as the ice sheets are melting due to climatic changes, there are still parts of the Arctic that will remain frozen year-round for the foreseeable future. O’Rourke, supra, at 16. Even though Shell Oil halted its exploration of the Arctic, U.S. oil companies are likely one day to resume exploring the oil and gas resources of the Arctic, as it is believed to contain more than 30 percent of the world’s potential energy resources. ADM Robert J.

Papp Jr., the U.S. envoy to the Arctic Council, made this remark and others at a recent House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing on the Arctic. U.S.

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, Statement of Admiral Robert J. Papp, Jr., Before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, and Emerging Threats (Dec. 10, 2014), available at http://docs.house.gov/ meetings/FA/FA14/20141210/102783/HHRG-113FA14-Wstate-PappJrR-20141210.pdf. Shipping companies are beginning to talk of using the Northwest Passage as a shipping route and International Environmental and Resources Law Committee, March 2016 . cruise companies are already building larger cruise ships to explore the far reaches of these now-open seas. Crystal Cruise Lines, for one, is advertising a new itinerary around Alaska into the Beaufort Sea through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and on to Greenland. See Crystal Cruises, Northwest Passage, http://www.crystalcruises.com/northwestpassage-cruise (last visited Jan. 25, 2016). With this increase in commerce and recreation and renewed recognition of U.S.

national security interests in the Arctic, it is more imperative than ever that the Coast Guard have the requisite fleet, especially icebreakers, to patrol these dangerous waters and monitor activities. With new icebreakers, the Coast Guard, with other agencies, can respond to their ever rapidly expanding missions in the Arctic and enhance its ability to monitor and report on the impact of the rapidly changing Arctic climate. As President Obama stated in his September 2015 visit to the Arctic, “[c]limate change is reshaping the Arctic in profound ways.” Press Release, White House, Fact Sheet: President Obama Announces New Investments to Enhance Safety and Security in the Changing Arctic (Sept.

1, 2015), https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-pressoffice/2015/09/01/fact-sheet-president-obamaannounces-new-investments-enhance-safety-and. Certainly, Russia is building up its icebreaker fleet to explore its Arctic oil and gas resources and pursue aggressively what it views as its national interest in the Arctic. Russia has a fleet of over 40 icebreakers and is building more. See Barbora Padrtova, Russia Approach Towards the Arctic Region, CENAA (2012), http://cenaa. org/analysis/russian-approach-towards-thearctic-region/.

Russia is also willing to defend its right to Arctic oil and gas “with missiles,” according to a German newspaper article from 2015. See, e.g., Vladimir Baranov, Russia Will Defend Its Right to Arctic Oil, Gas with Missiles, SPUTNIK INT’L, Oct. 2, 2015, http:// sputniknews.com/russia/20151002/1027910073/ russia-arctic-resources-missiles.html.

For all these reasons, it is imperative that the United States has its own fleet of modern icebreakers. Building and Funding New U.S. Icebreakers During a visit to Alaska in the fall of 2015, President Obama stepped up the administration’s efforts in the Arctic and announced that he would accelerate the acquisition of new Coast Guard icebreakers to 2020 from an original planning date of 2022. Press Release, White House, Fact Sheet: President Obama Announces New Investments to Enhance Safety and Security in the Changing Arctic (Sept.

1, 2015), https://www. whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/09/01/ fact-sheet-president-obama-announces-newinvestments-enhance-safety-and. As a result of this announcement, the Coast Guard began initial planning to acquire at least one new icebreaker and initiated a program of “aggressive industry outreach” according to Coast Guard acquisition chief, RADM Mike Haycock. See Megan Eckstein, Coast Guard to Finalize Icebreaker Acquisition Strategy by Spring; Production by 2020, USNI NEWS, Dec.

9, 2015, 4:53 PM, http://news.usni. org/2015/12/09/coast-guard-to-finalize-icebreakeracquisition-strategy-by-spring-production-by-2020. The Coast Guard also signed agreements with Canada and Finland to leverage their research on icebreaker design and capabilities. Id. And, an Industry Day will be held in March 2016. The real conundrum is how and who will pay for the new icebreakers.

They are estimated to cost about one billion dollars apiece and the Coast Guard is already strapped for resources. O’Rourke, supra. Its acquisition and construction budget is dedicated first to the procurement of new offshore patrol cutters and then to the replacement of its aircraft, according to Vice Admiral (VADM) Michel, Vice Commandant, U.S.

Coast Guard, testifying before a House Foreign Affairs Joint Subcommittee hearing in November 2015. Testimony of Vice Admiral Charles D. Michel, Before the House Foreign Affairs Committee— Europe, Eurasia, and Emerging Threats and Western Hemisphere Subcommittees (Nov. 17, 2015), available at http://docs.house.gov/meetings/ FA/FA14/20151117/104201/HHRG-114-FA14Wstate-MichelC-20151117.pdf.

There is literally no money in the current Coast Guard budget to International Environmental and Resources Law Committee, March 2016 15 . acquire a new icebreaker, let alone a fleet of them. Congress will have to think “outside of the box” to increase this budget. com/2015/09/01/reuters-america-huntington-ingallscites-interest-in-building-new-us-icebreakers.html. Conclusions Options for Funding New Icebreakers and U.S. Capacity to Build the Same At a November 17, 2015, joint hearing held by the Subcommittees on Europe, Eurasia, and Emerging Threats and the Western Hemisphere of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Subcommittee Chairman Dana Rohrabacher (R-CA) suggested that the Coast Guard consider leasing an icebreaker or acquiring one from Finland. Leasing icebreakers has been considered several times in the last couple of decades, but the lack of legal authority and opposition from industry and labor have quashed any real consideration of this alternative. In the final hours of the first session of the 114th Congress, Congress passed an omnibus appropriations bill that increased the planning budget for new Coast Guard icebreakers to six million dollars for FY2016. Both the House and the Senate passed Coast Guard authorization bills, and final passage occurred on February 1, 2016.

The final bill will permit the Coast Guard to use “incremental funding” for the acquisition of icebreakers. But even with incremental funding, it would take five to ten years to fully fund a new icebreaker, and this could require a significant increase to the Coast Guard’s acquisition budget. To fulfill the Coast Guard’s mission and allow the United States to build new icebreakers, funding cannot just come from the Coast Guard’s budget, but also from other agencies that rely on the Coast Guard for research and logistical assistance in the Arctic and Antarctic, including the U.S. Navy, NSF (with its base in McMurdo), and NOAA.

Keeping a presence in the Arctic is critical for national security as well as for the conduct of oceanic and atmospheric research in the Arctic and Antarctic. U.S. shipyards have the capacity to build the icebreakers. For example, Huntington Ingalls Industries in Mississippi expressed an interest in building polar icebreakers.

See Andrea Shalal, Huntington Ingalls Cites Interest in Building New U.S. Icebreakers, REUTERS, Sept. 1, 2015, http://www.cnbc. 16 The United States has taken the first steps toward acquiring at least one new icebreaker, but this should not be the end of the story. To accomplish the tasks that Congress and the administration have set for it, and to protect our vital interests in the Arctic—and Antarctic—the Coast Guard needs at least two new icebreakers.

Congress must find a way to fund them through incremental funding, borrowing from other agencies, and/or creative budget scoring. In any case, our national interest demands that Congress and the administration find the funding to build icebreakers, even if it means “breaking the mold” in providing the appropriations to do so. The construction of new icebreakers will provide excellent work for the U.S.

shipbuilding industry, allow it to upgrade its capabilities, enable the United States to compete with Russia in the Arctic, and protect our national security interests in both the Arctic and Antarctic. Joan Bondareff, Of Counsel at Blank Rome, represents a wide range of industry clients as well as state and local governments in matters related to maritime regulations and public policy, environmental law, government relations, international law, federal grants, and port security. She previously served as Chief Counsel and Acting Deputy Administrator of the Maritime Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, and as former Majority Counsel for the House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries.

She is a current appointee to the Pool of Experts of the Regular Process for Global Reporting and Assessment of the State of the Marine Environment, including socioeconomic aspects. Jim Ellis, Of Counsel at Blank Rome, is an experienced negotiator in both the public and private sectors who focuses on complex corporate transactions and regulatory matters for clients in the global maritime and transportation industry. Mr. Ellis previously served in the U.S. Coast Guard, rising to the rank of commander, and served as Deputy U.S.

Representative to the UN Law of the Sea Conference for transportation issues. He also served as Senior Legal Counsel for the Coast Guard in Alaska, and currently serves as a Fellow for the Center for Arctic Study and Policy at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy. International Environmental and Resources Law Committee, March 2016 .

International Environmental and Resources Law Committee Newsletter Vol. 18, No. 2, March 2016 Shannon Dilley and Jonathan Nwagbaraocha, Editors AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION SECTION OF ENVIRONMENT, ENERGY, AND RESOURCES CALENDAR OF SECTION EVENTS CALENDAR OF SECTION EVENTS In this issue: Chair Message Stephanie Altman, R. Juge Gregg, Niki L.

Pace, Fatima Maria Ahmad, and Anastasia Telesetsky .............................3 Polar Opposites: Should Arctic Environmental Governance Follow the Antarctic Model? Mark P. Nevitt and Robert V. Percival ..................................4 Under the Ice: Arctic Nations Seek to Curb Commercial Fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean Fred Turner ..............................................9 The U.S.

Imperative for New Icebreakers Joan M. Bondareff and James B. Ellis..........................................13 Fulï¬lling Tribal Trust and Arctic Responsibilities: U.S.

Co-Management of Marine Resources Kathryn Mengerink, Greta Swanson, and David Roche ........................................17 A Canadian Perspective on Key Arctic Issues: Governance, Resource Development, and Navigation Tony Crossman and Nardia Chernawsky .............................21 A Royal Dutch Pain: Summary of the Challenges and Regulatory Gaps in Arctic Offshore Drilling Jonathon D. Green ..............................24 March 29-30, 2016 34th Water Law Conference Austin, TX March 30-April 1, 2016 45th Spring Conference Austin, TX April 12-16, 2016 SIL Spring 2016 Meeting New York, NY June 14, 2016 Key Environmental Issues in U.S. EPA Region 5 Conference Chicago, IL October 18-22, 2016 SIL Fall 2016 Meeting Tokyo, Japan For full details, please visit www.ambar.org/EnvironCalendar Copyright © 2016.

American Bar Association. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Send requests to Manager, Copyrights and Licensing, at the ABA, by way of www.americanbar.org/reprint. Any opinions expressed are those of the contributors and shall not be construed to represent the policies of the American Bar Association or the Section of Environment, Energy, and Resources. 2 International Environmental and Resources Law Committee, March 2016 .

THE U.S. IMPERATIVE FOR NEW ICEBREAKERS Joan M. Bondareff and James B. Ellis Executive Summary The U.S.

Coast Guard, under new guidance from President Barack Obama, is moving forward to acquire one new polar icebreaker for the United States. However, the United States, as a leading maritime power and Arctic nation, needs more icebreakers and has yet to determine how to fund these very expensive ships. This article describes the United States’ disappointing history with polar icebreakers and why they are badly needed. Background The U.S.

Coast Guard is the primary maritime law enforcement agency of the United States. This role includes search and rescue, especially in the Arctic where the Coast Guard provides ships for other government agencies that have no capabilities in ice-covered areas. The Coast Guard also provides support to the U.S.

research station in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. As early as the 1800s, the Coast Guard and its predecessor, the Revenue Cutter Service, operated vessels with ice-breaking capabilities. As recently as the mid-1970s, the Coast Guard had five heavy polar icebreakers in its fleet. In 1976, the Coast Guard added two new heavy icebreakers—the Polar Sea and the Polar Star.

However, by 1990, they were the only remaining polar icebreakers in the fleet. In 2000, the Healy, a third, medium icebreaker was added. The Polar Sea and the Polar Star are approaching 40 years of service, and the Polar Sea is no longer operational, leaving the nation with only one heavy and one medium icebreaker.

At the same time, the U.S. role in the Arctic has expanded due to the melting icecap, opening of new shipping lanes, and expanded tourism from cruise ships in the Arctic. Yet the United States lacks the capacity to fully monitor these activities and conduct any needed search and rescue operations.

There is no viable plan for how to address the replacement of these aging vessels, much less how to bridge the five- to ten-year gap before a new icebreaker can be designed, built, and placed in operation. Congressional Interest in New Icebreakers For some, it is unthinkable that a great maritime power such as the United States would lack sufficient icebreakers to ply the frozen waters of the Arctic and the Antarctic and protect its national interests. This is in contrast to Russia whose icebreaker fleet numbers more than 40 and has 11 more in production. Ronald O’Rourke, Coast Guard Polar Icebreaker Modernization: Background and Issues for Congress, CONG. RESEARCH SERV., RL34391, at 11 (Jan.

15, 2016). Over the past two decades, various federal agencies, congressional committees, and academic and nonprofit institutions have completed a number of reports that recognized the need for a long-term plan to ensure that there were adequate icebreaking vessels available to carry out activities in the polar regions that were important to U.S. national interests, but no real action has been taken to address this growing crisis. The cost of building a new heavy icebreaker is estimated to be on the order of one billion dollars—a figure that, to date, neither the executive branch nor Congress has been willing to fund. We as a nation now find ourselves on the precipice of a major crisis in how to provide the resources necessary to protect our national interest in the Arctic.

There are, however, glimmers of hope for congressional support for the acquisition of at least one new icebreaker. Senator Murkowski from Alaska has intimated her support for funding the new icebreaker. This article argues for the need for the United States to build two or more icebreakers, to have them built in U.S. shipyards, and to have them acquired through incremental payments over a five- to ten-year period with contributions from other related federal agencies (e.g., the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the U.S.

Navy). International Environmental and Resources Law Committee, March 2016 13 . Why U.S. Icebreakers? The United States is not only a maritime nation, but also an Arctic nation. Despite this, the United States had not placed a high priority on pursuing its national interest in the Arctic. Only in the last few years as climate change, potential energy development in the region, and a high level of activity by Russia in the region, has the United States begun to focus more intensely on our national interests in the Arctic.

In fact, the United States is currently chairing the eight-member Arctic Council. The Obama administration developed a strategic plan for the Arctic in 2013, and in 2014, it developed an implementation plan for the Arctic. The White House, Implementation Plan for the National Strategy for the Arctic Region (Jan. 2014), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/ default/files/docs/implementation_plan_for_the_ national_strategy_for_the_arctic_region_-_fi.... pdf. The Alaska Arctic Policy Commission, in 2015, issued a report stating that “[t]he Arctic is an integral part of Alaska’s Identity.” Alaska Arctic Policy Commission, Final Report and Implementation Plan, Executive Summary, 2 (Jan.

30, 2015), available at http://www.akarctic. com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/AAPC_Exec_ Summary_lowres.pdf. The administration’s heightened commitment to the Arctic was highlighted further during President Obama’s trip to Alaska in the fall of 2015. At this writing, we are waiting to see if his FY2017 budget request reflects this commitment. The United States has a vast Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) that extends around the coasts of the United States and its territories seaward to 200 nautical miles, and it also has an extended continental shelf under the sea adjacent to the Alaskan coast that could extend more than 600 nautical miles under the boundary principles recognized by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

The United States recognizes these maritime principles as part of customary international law even though it has not ratified UNCLOS. See Ronald Reagan, 14 Proclamation 5030—Exclusive Economic Zone of the United States of America, American Presidency Project (Mar. 10, 1983), http://www.presidency. ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=41037. Russia has filed and amended a formal claim for an extended continental shelf with the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS).

See United Nations, Ocean & Law of the Sea, Commission on the Limits of the Continental shelf (CLCS) Outer Limits of the Continental Shelf Beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Baselines: Submissions to the Commission: Submission by the Russian Federation, http://www.un.org/Depts/los/ clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_rus.htm (last visited Jan. 30, 2016). This contrasts with the United States, which is still collecting data on the outer limits of its continental shelf and has not yet made a formal claim with the CLCS.

The United States is also hampered from protecting its claim because it is not an official member of CLCS due to its failure to ratify UNCLOS. Although the frozen Arctic landscape is less frozen these days as the ice sheets are melting due to climatic changes, there are still parts of the Arctic that will remain frozen year-round for the foreseeable future. O’Rourke, supra, at 16. Even though Shell Oil halted its exploration of the Arctic, U.S. oil companies are likely one day to resume exploring the oil and gas resources of the Arctic, as it is believed to contain more than 30 percent of the world’s potential energy resources. ADM Robert J.

Papp Jr., the U.S. envoy to the Arctic Council, made this remark and others at a recent House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing on the Arctic. U.S.

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, Statement of Admiral Robert J. Papp, Jr., Before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, and Emerging Threats (Dec. 10, 2014), available at http://docs.house.gov/ meetings/FA/FA14/20141210/102783/HHRG-113FA14-Wstate-PappJrR-20141210.pdf. Shipping companies are beginning to talk of using the Northwest Passage as a shipping route and International Environmental and Resources Law Committee, March 2016 . cruise companies are already building larger cruise ships to explore the far reaches of these now-open seas. Crystal Cruise Lines, for one, is advertising a new itinerary around Alaska into the Beaufort Sea through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and on to Greenland. See Crystal Cruises, Northwest Passage, http://www.crystalcruises.com/northwestpassage-cruise (last visited Jan. 25, 2016). With this increase in commerce and recreation and renewed recognition of U.S.

national security interests in the Arctic, it is more imperative than ever that the Coast Guard have the requisite fleet, especially icebreakers, to patrol these dangerous waters and monitor activities. With new icebreakers, the Coast Guard, with other agencies, can respond to their ever rapidly expanding missions in the Arctic and enhance its ability to monitor and report on the impact of the rapidly changing Arctic climate. As President Obama stated in his September 2015 visit to the Arctic, “[c]limate change is reshaping the Arctic in profound ways.” Press Release, White House, Fact Sheet: President Obama Announces New Investments to Enhance Safety and Security in the Changing Arctic (Sept.

1, 2015), https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-pressoffice/2015/09/01/fact-sheet-president-obamaannounces-new-investments-enhance-safety-and. Certainly, Russia is building up its icebreaker fleet to explore its Arctic oil and gas resources and pursue aggressively what it views as its national interest in the Arctic. Russia has a fleet of over 40 icebreakers and is building more. See Barbora Padrtova, Russia Approach Towards the Arctic Region, CENAA (2012), http://cenaa. org/analysis/russian-approach-towards-thearctic-region/.

Russia is also willing to defend its right to Arctic oil and gas “with missiles,” according to a German newspaper article from 2015. See, e.g., Vladimir Baranov, Russia Will Defend Its Right to Arctic Oil, Gas with Missiles, SPUTNIK INT’L, Oct. 2, 2015, http:// sputniknews.com/russia/20151002/1027910073/ russia-arctic-resources-missiles.html.

For all these reasons, it is imperative that the United States has its own fleet of modern icebreakers. Building and Funding New U.S. Icebreakers During a visit to Alaska in the fall of 2015, President Obama stepped up the administration’s efforts in the Arctic and announced that he would accelerate the acquisition of new Coast Guard icebreakers to 2020 from an original planning date of 2022. Press Release, White House, Fact Sheet: President Obama Announces New Investments to Enhance Safety and Security in the Changing Arctic (Sept.

1, 2015), https://www. whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/09/01/ fact-sheet-president-obama-announces-newinvestments-enhance-safety-and. As a result of this announcement, the Coast Guard began initial planning to acquire at least one new icebreaker and initiated a program of “aggressive industry outreach” according to Coast Guard acquisition chief, RADM Mike Haycock. See Megan Eckstein, Coast Guard to Finalize Icebreaker Acquisition Strategy by Spring; Production by 2020, USNI NEWS, Dec.

9, 2015, 4:53 PM, http://news.usni. org/2015/12/09/coast-guard-to-finalize-icebreakeracquisition-strategy-by-spring-production-by-2020. The Coast Guard also signed agreements with Canada and Finland to leverage their research on icebreaker design and capabilities. Id. And, an Industry Day will be held in March 2016. The real conundrum is how and who will pay for the new icebreakers.

They are estimated to cost about one billion dollars apiece and the Coast Guard is already strapped for resources. O’Rourke, supra. Its acquisition and construction budget is dedicated first to the procurement of new offshore patrol cutters and then to the replacement of its aircraft, according to Vice Admiral (VADM) Michel, Vice Commandant, U.S.

Coast Guard, testifying before a House Foreign Affairs Joint Subcommittee hearing in November 2015. Testimony of Vice Admiral Charles D. Michel, Before the House Foreign Affairs Committee— Europe, Eurasia, and Emerging Threats and Western Hemisphere Subcommittees (Nov. 17, 2015), available at http://docs.house.gov/meetings/ FA/FA14/20151117/104201/HHRG-114-FA14Wstate-MichelC-20151117.pdf.

There is literally no money in the current Coast Guard budget to International Environmental and Resources Law Committee, March 2016 15 . acquire a new icebreaker, let alone a fleet of them. Congress will have to think “outside of the box” to increase this budget. com/2015/09/01/reuters-america-huntington-ingallscites-interest-in-building-new-us-icebreakers.html. Conclusions Options for Funding New Icebreakers and U.S. Capacity to Build the Same At a November 17, 2015, joint hearing held by the Subcommittees on Europe, Eurasia, and Emerging Threats and the Western Hemisphere of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Subcommittee Chairman Dana Rohrabacher (R-CA) suggested that the Coast Guard consider leasing an icebreaker or acquiring one from Finland. Leasing icebreakers has been considered several times in the last couple of decades, but the lack of legal authority and opposition from industry and labor have quashed any real consideration of this alternative. In the final hours of the first session of the 114th Congress, Congress passed an omnibus appropriations bill that increased the planning budget for new Coast Guard icebreakers to six million dollars for FY2016. Both the House and the Senate passed Coast Guard authorization bills, and final passage occurred on February 1, 2016.

The final bill will permit the Coast Guard to use “incremental funding” for the acquisition of icebreakers. But even with incremental funding, it would take five to ten years to fully fund a new icebreaker, and this could require a significant increase to the Coast Guard’s acquisition budget. To fulfill the Coast Guard’s mission and allow the United States to build new icebreakers, funding cannot just come from the Coast Guard’s budget, but also from other agencies that rely on the Coast Guard for research and logistical assistance in the Arctic and Antarctic, including the U.S. Navy, NSF (with its base in McMurdo), and NOAA.

Keeping a presence in the Arctic is critical for national security as well as for the conduct of oceanic and atmospheric research in the Arctic and Antarctic. U.S. shipyards have the capacity to build the icebreakers. For example, Huntington Ingalls Industries in Mississippi expressed an interest in building polar icebreakers.

See Andrea Shalal, Huntington Ingalls Cites Interest in Building New U.S. Icebreakers, REUTERS, Sept. 1, 2015, http://www.cnbc. 16 The United States has taken the first steps toward acquiring at least one new icebreaker, but this should not be the end of the story. To accomplish the tasks that Congress and the administration have set for it, and to protect our vital interests in the Arctic—and Antarctic—the Coast Guard needs at least two new icebreakers.

Congress must find a way to fund them through incremental funding, borrowing from other agencies, and/or creative budget scoring. In any case, our national interest demands that Congress and the administration find the funding to build icebreakers, even if it means “breaking the mold” in providing the appropriations to do so. The construction of new icebreakers will provide excellent work for the U.S.

shipbuilding industry, allow it to upgrade its capabilities, enable the United States to compete with Russia in the Arctic, and protect our national security interests in both the Arctic and Antarctic. Joan Bondareff, Of Counsel at Blank Rome, represents a wide range of industry clients as well as state and local governments in matters related to maritime regulations and public policy, environmental law, government relations, international law, federal grants, and port security. She previously served as Chief Counsel and Acting Deputy Administrator of the Maritime Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, and as former Majority Counsel for the House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries.

She is a current appointee to the Pool of Experts of the Regular Process for Global Reporting and Assessment of the State of the Marine Environment, including socioeconomic aspects. Jim Ellis, Of Counsel at Blank Rome, is an experienced negotiator in both the public and private sectors who focuses on complex corporate transactions and regulatory matters for clients in the global maritime and transportation industry. Mr. Ellis previously served in the U.S. Coast Guard, rising to the rank of commander, and served as Deputy U.S.

Representative to the UN Law of the Sea Conference for transportation issues. He also served as Senior Legal Counsel for the Coast Guard in Alaska, and currently serves as a Fellow for the Center for Arctic Study and Policy at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy. International Environmental and Resources Law Committee, March 2016 .