Pathetically Pathological – a Stumble Through the Maze of Dispute Resolution Clauses – Winter 2015

Andrews Kurth

Description

Winter 2015

Editor: Melanie Willems

. IN THIS ISSUE

03

07

15

Pathetically pathological—a stumble through the maze

of defective dispute resolution clauses

by Melanie Willems

Excluding consequential loss—does it matter if you’ve

been naughty or nice?

by Markus Esly

Winter is coming: the expanding definition of assets in

freezing injunctions

by Ryan Deane

THE ARBITER

WINTER 2015

2

. Pathe cally pathological—

a stumble through the

maze of defec ve dispute

resolu on clauses?

Should

arbitral

Ins tu ons such as the ICC or the LCIA pro-

ins tu on administer

an

vide administra ve support, and publish

the proceedings?

their own set of (tried and tested) procedural rules for any arbitra on proceedings under their auspices. They can also assist with

appoin ng arbitrators. The involvement of

ins tu ons is not, however, compulsory or

necessary. Whether you should use one will

by Melanie Willems

depend on each case - check with your arbi-

Arbitra on is intended to be a more efficient

and commercial alterna ve to li ga ng in the

courts.

As we all know, arbitra on is strictly tra on lawyer. How many arbitra- A tribunal usually consists of either one or tors? three arbitrators. Some ins tu onal rules consensual and contractual. The basic princi- have a preference in favour of one or the ple is that absent agreement, nobody can be other. compelled to arbitrate, so the arbitra on whether to leave this point open in the clause is of fundamental importance.

In this contract) is something that is best consid- ar cle, we look at some recent decisions illustra ng how far the English Courts will go in helping par es who The ideal size of the tribunal (or ered in each par cular case. A reminder: what to address in your arbitra on clause In an ideal world, there is a fairly lengthy ‘wish list’ of procedural The par es have complete freedom of language of the arbi- have signed up to a defec ve arbitra on. What should be the choice in this regard. tra on proceedings? Where should arbitra on the Again, the par es have complete freedom of hearings choice, but they need to choose their words take place? carefully. References to a ‘venue’ or a or administra ve ma ers that the par es ought to address in their ‘place’ of the arbitra on may be taken to arbitra on clause. There are also a number of legal systems (or amount to a choice of the juridical seat, not ‘applicable laws’) that come into play - and it is here that difficul es just the physical loca on of the hearing. can arise. The following may serve as a reminder: Key procedural ma er Should there be any What kind of disputes It generally makes most sense to provide that should be referred to each and every dispute that relates to the arbitra on? contract, or which arises out of or in connecon with the contract, should be referred to arbitra on (so including claims in tort, equitable claims and claims about the validity or termina on of the contract). English law strives to construe arbitra on clauses generously - they cast a very wide net over the types of dispute that may arise. binding, but some seats provide for a the Op ons for the par es Arbitra on awards are meant to be ï¬nal and right of appeal from (usually limited) right to appeal.

If this is not sion? tribunal’s deci- desired, it needs to be expressly excluded. The appeal on a point of law under Sec on 69 of the English Arbitra on Act 1996 is an example of a right that can be excluded by the par es contractually. Note that by adop ng the rules of arbitra on of a major ins tu on such as the ICC and the LCIA, rights of recourse against an award are likely to be limited to ma ers that the par es cannot exclude as a ma er of law, such as serious procedural irregulari es, bias on the part of the tribunal or lack of due process. THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 3 . Choices implica ng Op ons for the par es a jurisdic on or an • Whether the subject ma er of any par cular dispute is legally capably of being referred to arbitra on. This is What is the seat of the The choice of the seat of the arbitra on called ‘arbitrability’, and it can give rise arbitra on? to unforeseen complica ons. By way brings with it the supervisory jurisdic on of the local courts in that jurisdic on, applying of example, the na onal arbitra on their own local laws governing arbitra on laws of some jurisdic ons may exclude proceedings. Those courts, and the local disputes over natural resources or laws, are likely to be the ï¬rst, or perhaps the other interests deemed to be of na- exclusive, port of call for key ma ers such onal strategic importance from the as: • jurisdic on of any arbitral tribunal. Gran ng interim, provisional or suppor ve measures that require the backing of the judicial, or state, enforcement mechanism with contempt What is the governing The arbitra on clause itself is generally law of the arbitra on understood to be self-standing and separate clause? has its own governing law, which may well of court as the ul mate sanc on (such differ from the law governing the main as effec ve freezing injunc ons or agreement between the par es. orders compelling the a endance of witnesses). Issues rela ng to the substan ve validity, Welcome court support scope and meaning of the arbitra on agree- can some mes turn into unwelcome ment (including issues as to the scope of the court interven on, so the seat should tribunal's jurisdic on) are governed by the be chosen carefully. • proper law of the arbitra on agreement. Rules safeguarding due process of the arbitra on proceedings, Many arbitra on clauses omit to specify this including governing law, and so it falls to the courts of standards of impar ality and fairness the seat or the arbitral tribunal to determine required of arbitrators, and the mecha- this. For example, the English Court of Ap- nism for challenges to, and removal or peal has said that absent an express choice disqualiï¬ca on, of arbitrators. • from the underlying contract.

It therefore governing the arbitra on clause, the court Enforcing the arbitra on agreement, will look to see whether there has been an including the applica on of any speciï¬c implied choice. They will consider the clos- formal requirements (i.e. does the est and most real connec on between the arbitra on agreement have to be in a arbitra on clause and any applicable law par cular form in wri ng?).

The courts (Sulamerica CIA Nacional de Seguros SA v of the seat may also assist in restrain- Enesa Engenharia SA [2012] EWCA Civ 638). ing tac cal, or troublesome, li ga on Applying that test can lead to the arbitra on that is commenced in breach of the agreement being governed by the law of the arbitra on in another jurisdic on. The seat, and not the law of the underlying con- par es should inves gate whether tract. effec ve injunc ve relief is available from the courts in this regard. • What is the governing The governing law of the contract will deter- Challenging or enforcing the award. law of the contract? mine the substan ve rights and obliga ons The courts of the seat should have the of the par es, and will be applied to decide ï¬nal word in determining any challeng- the claims on the merits. Again, the par es es to the award (or purported appeals). have freedom of choice, but it is a choice They may also be asked to enforce the that should not be made lightly.

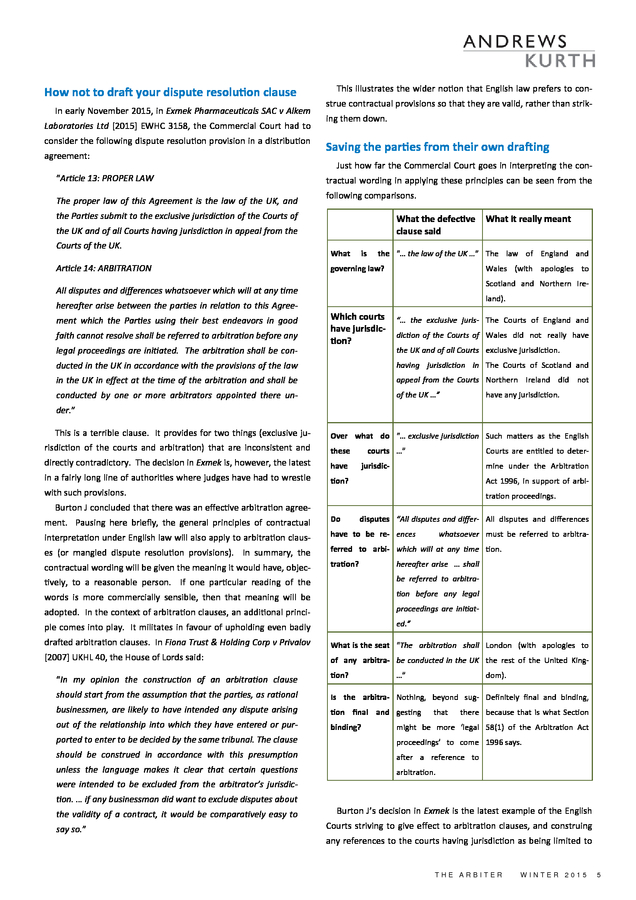

The govern- award. ing law can have a very real impact on the outcome of any dispute. 4 THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 . How not to dra your dispute resolu on clause In early November 2015, in Exmek Pharmaceu cals SAC v Alkem Laboratories Ltd [2015] EWHC 3158, the Commercial Court had to consider the following dispute resolu on provision in a distribu on agreement: This illustrates the wider no on that English law prefers to construe contractual provisions so that they are valid, rather than striking them down. Saving the par es from their own dra ing Just how far the Commercial Court goes in interpre ng the con- “Ar cle 13: PROPER LAW The proper law of this Agreement is the law of the UK, and tractual wording in applying these principles can be seen from the following comparisons. the Par es submit to the exclusive jurisdic on of the Courts of What the defec ve clause said the UK and of all Courts having jurisdic on in appeal from the Courts of the UK. Ar cle 14: ARBITRATION What is the “… the law of the UK …” The law of England and governing law? Wales (with apologies to Scotland and Northern Ire- All disputes and differences whatsoever which will at any me land). herea er arise between the par es in rela on to this Agreement which the Par es using their best endeavors in good faith cannot resolve shall be referred to arbitra on before any legal proceedings are ini ated. The arbitra on shall be con- What it really meant Which courts have jurisdicon? “… the exclusive juris- The Courts of England and dic on of the Courts of Wales did not really have the UK and of all Courts exclusive jurisdic on. ducted in the UK in accordance with the provisions of the law having jurisdic on in The Courts of Scotland and in the UK in effect at the me of the arbitra on and shall be appeal from the Courts Northern Ireland did not conducted by one or more arbitrators appointed there un- of the UK …” have any jurisdic on. der.” This is a terrible clause. It provides for two things (exclusive ju- Over what do “… exclusive jurisdic on Such ma ers as the English risdic on of the courts and arbitra on) that are inconsistent and these directly contradictory. The decision in Exmek is, however, the latest have in a fairly long line of authori es where judges have had to wrestle on? courts …” Courts are en tled to deter- jurisdic- mine under the Arbitra on Act 1996, in support of arbi- with such provisions. tra on proceedings. Burton J concluded that there was an effec ve arbitra on agreedisputes “All disputes and differ- All disputes and differences ment.

Pausing here briefly, the general principles of contractual Do interpreta on under English law will also apply to arbitra on claus- have to be re- ences es (or mangled dispute resolu on provisions). In summary, the ferred to arbi- which will at any me contractual wording will be given the meaning it would have, objec- tra on? whatsoever must be referred to arbitraon. herea er arise … shall vely, to a reasonable person. If one par cular reading of the be referred to arbitra- words is more commercially sensible, then that meaning will be on before any legal adopted.

In the context of arbitra on clauses, an addi onal princi- proceedings are ini at- ple comes into play. It militates in favour of upholding even badly ed.” dra ed arbitra on clauses. In Fiona Trust & Holding Corp v Privalov What is the seat “The arbitra on shall London (with apologies to [2007] UKHL 40, the House of Lords said: of any arbitra- be conducted in the UK the rest of the United King- “In my opinion the construc on of an arbitra on clause should start from the assump on that the par es, as ra onal businessmen, are likely to have intended any dispute arising out of the rela onship into which they have entered or pur- on? …” dom). Is the arbitra- Nothing, beyond sug- Deï¬nitely ï¬nal and binding, on ï¬nal and ges ng binding? that there because that is what Sec on might be more ‘legal 58(1) of the Arbitra on Act ported to enter to be decided by the same tribunal.

The clause proceedings’ to come 1996 says. should be construed in accordance with this presump on a er a reference to unless the language makes it clear that certain ques ons arbitra on. were intended to be excluded from the arbitrator’s jurisdicon. … if any businessman did want to exclude disputes about the validity of a contract, it would be compara vely easy to say so.” Burton J’s decision in Exmek is the latest example of the English Courts striving to give effect to arbitra on clauses, and construing any references to the courts having jurisdic on as being limited to THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 5 . the supervisory powers given to the court in support of arbitra on arbitra on clause that was internally inconsistent. The problem in proceedings under the Arbitra on Act 1996 (other decisions in- that clause was that the objec ve reader did not know which kind clude Axa Re v Ace Global Markets Ltd [2006] EWHC 216 and Paul of arbitra on the par es had wanted, rather than the par es say- Smith v H&S Interna onal Holding Inc [1991] 2 Lloyd's Law Rep). ing that they wanted ‘court and arbitra on’ to apply. Arbitra on tends to win out where it makes an appearance in In Shagang South-Asia (Hong Kong) Trading Co Ltd v Daewoo the contract, even in the face of references to the jurisdic on, or Logis cs [2015] EWHC 194, the Commercial Court set aside an arbi- exclusive jurisdic on, of the Courts elsewhere. No doubt there is tra on award because the arbitrator had been appointed in the legal policy at play here, for it is difficult to jus fy how such incon- wrong seat. The decision illustrates that while the Courts will strive sistent clauses can be construed harmoniously by reference to the to uphold an unclear arbitra on clause, they are less likely to step established principles of contractual interpreta on (of which in and help a party who has embarked on the ‘wrong kind’ of arbi- ‘rewri ng the clause so that it makes sense’ is not one). tra on proceedings under an ambiguous clause. If certain courts are given exclusive jurisdic on, then it is a leap The arbitral seat is the juridical base of the arbitra on.

By se- to say that this exclusivity is meant to apply only to a very limited lec ng a given state as the seat of arbitra on, the par es place aspect of what would ordinarily fall within the purview of the their arbitral process within the framework of that state's na onal courts - be it the supervisory func ons in support of arbitral pro- laws. The law of the seat (lex arbitri, or curial law) will deï¬ne many ceedings, or (perhaps even more ar ï¬cially) only those disputes of the procedural aspects of the arbitra on. Although the seat is that arise under the par cular provision in which the par es made frequently the same as the hearing loca on, it does not have to be. reference to the courts. The la er situa on arose in Shell Interna onal Petroleum Co Ltd v Coral Oil Co Ltd [1999] 1 Lloyd's Law Rep 72.

The pathological clause in that case stated: Shagang was a dispute concerning a cargo of steel that had been shipped out of China. The cargo was not discharged at the port of des na on. The party who was meant to have received the steel incurred substan al costs.

A se lement was reached, and the owners of the vessel sought to pass the loss on to the charterers. The two key clauses of the ï¬xture note for the charterparty “13. Applicable law (usually a short document) provided: This Agreement, its interpreta on and the rela onship of the par es hereto shall be governed and construed in accordance with English law and any dispute under this provision shall be referred to the jurisdic on of the English Courts.” There are no prizes for guessing that Clause 14 went on to state that every dispute had to be submi ed to arbitra on. The way in which the court construed these two provisions harmoniously was to say that the English Courts had jurisdic on over all disputes concerning the applicable law.

On that basis, if a party to this contract wanted to make a hopeless argument that any law other than that of England and Wales applied to anything regarding this contract, they had to go to the Commercial Court to be told ‘no’. On this “23. ARBITRATION: ARBITRATION TO BE HELD IN HONG KONG. ENGLISH LAW TO BE APPLIED. 24. OTHER TERMS/CONDITIONS AND CHARTER PARTY DETAILS BASE ON GENCON 1994 CHARTER PARTY.” The Gencon 1994 form consisted of numbered boxes to be ï¬lled in.

One such box was intended to deal with the arbitra on clause for the charterparty in more detail than one would usually ï¬nd on the ï¬xture note. It listed out a number of sub-clauses of Clause 19, which all set out different arbitra on proceedings. One of the provision was Clause 19 (a), which provided as follows: reading of the contract, arbitrators appointed under Clause 14 “This Charter Party shall be governed by and construed in faced with the same untenable sugges on in an arbitra on would accordance with English law and any dispute arising out of have to decline to say ‘no’, and ask the par es to have the Court this Charter Party shall be referred to arbitra on in London in decide the point.

It just seems implausible that any commercial accordance with the Arbitra on Acts 1950 and 1979 or any party would have agreed to this arrangement. One may (perhaps statutory modiï¬ca on or re-enactment thereof for the me safely) speculate that what really happened is that the par es being in force …” stopped paying close a en on to the contract when they reached Clause 13, and that, consequently, a mistake was made in what is s ll considered to be a ‘boilerplate’ clause. A contras ng approach Cases resolving conflicts between the courts and arbitra on may be in a special category. This seems apparent when considering a recent, contras ng, example of the English Courts construing an 6 THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 However, Gencon 1994 also said that Clause 19(a) would apply if the par es did not choose any of these op ons, which they had not done.

The claimants commenced arbitra on proceedings in London, and purported to appoint a sole arbitrator under Clause 19(a). If one were to take the holis c approach, and sought to construe the provision harmoniously, one might say that Clause 23 (“Arbitra on held in Hong Kong”) meant the place where the hear- . ings were to take place. The expression ‘holding a hearing’ does ‘venue’ se led the ques on in favour of London as the seat, and so not sound par cularly odd. It could well be what the par es meant overrode an express reference to Indian legisla on. The majority of here.

One might then go on to say that Clause 19(a) ought to have the provisions of the Indian Arbitra on Act would, however, only some meaning as well, as the par es do not lightly include superflu- apply if the seat of the arbitra on was India, so there seems to ous words (or even en re redundant clauses) in their contracts. have been li le point in making a reference to the whole statute This provision also states that it was to apply ‘by default’, which unless it was meant to apply. In this par cular case, one may won- points towards it being automa cally effec ve. The reference to der whether London as the seat did not beneï¬t from a home ad- the precursors of the Arbitra on Act 1996 suggests that this clause vantage in the Commercial Court. was intended to choose London as the seat.

This would produce a harmonious result, with English law governing both substance and Conclusion procedure of the arbitra on. Badly dra ed dispute resolu on clauses s ll abound. The num- That is not how the Court read the clause. Instead, Hamblen J ber of cases decided in the English Courts is testament to that. focused on Clause 23, no ng that it had two limbs, the ï¬rst sta ng These decisions also show that where the Courts and arbitra on where the arbitra on was “to be held”, and the second what law clash in conflic ng clauses, arbitra on is likely to prevail.

That bias was “to be applied”. Even though the par es had not made refer- is likely to reflect policy considera ons, as the English Courts are ence to the ‘place’ of the arbitra on (which is usually taken to strong supporters of arbitra on. In some of the decisions, howev- mean the seat), the link they had made between the arbitra on er, that support has led to the principles of contractual interpreta- and Hong Kong was sufficient to bring with it the choice of Hong on apparently being thrown overboard.

The ï¬nal word is, as al- Kong law as the law of the seat. As the judge explained at para- ways, pay close a en on to your arbitra on, and watch out for graphs 19 to 22: inconsistencies that will test the sanity of your lawyers creeping in. ï‚¥ required in rela on to that process. Agreeing that a law is Excluding consequen al loss—does it ma er if you’ve been naughty or nice? “to be applied” to disputes between par es is a common by Markus Esly “It is logical and sensible for a dispute resolu on clause to address both the issue of where and how disputes are to be resolved and the law governing such resolu on and such clauses commonly do so.

Agreeing that an arbitra on is “to be held” in a par cular country suggests that all aspects of the arbitra on process are to take place there. That would include any supervisory court proceedings which might be means of expressing a choice of substan ve law, a choice A empts to exclude or limit liability for con- that is frequently made express.” sequen al loss have given rise to considera- What of Clause 19(a)? The judge found that since the par es ble li ga on, across industries. As two re- had adopted Hong Kong as the seat, Clause 19(a) could have no cent decisions in the energy sector have illus- applica on as it was simply inconsistent. trated, adop ng apparently wide-ranging and While a governing is usually chosen expressly, the par es fre- legalis c phraseology in such clauses may not quently do not say anything about which curial law (the law of the have the desired result for the party seeking seat) they have chosen.

References to ‘holding’ an arbitra on to limit its exposure. somewhere, or it ‘taking place’ may well be taken to amount to a It remains paramount to say clearly and precisely in the contract choice of seat. In par cular, referring to the ‘venue’ for an arbitra- what losses are excluded. While English contract law generally on is par cularly likely to mean the seat.

In Enercon GmbH v allows the par es great freedom to allocate risk and liabili es, ex- Enercon (India) Ltd [2012] 1 Lloyds Rep. 519, the par es had agreed clusion and limita on clauses are construed narrowly such that a that: more balanced, fairer result might be achieved. In this ar cle, we revisit the basic principles governing damages “The venue of the arbitra on proceedings shall be London. for breach of contract and liability for ï¬nancial loss in par cular, The provisions of the Indian Arbitra on and Concilia on Act, before reviewing Transocean v Providence (2014), a dispute under a 1996 shall apply.” contract for the hire of a drilling rig, and Sco sh Power v BP Explo- Applying the Indian Arbitra on Act is inconsistent with the seat ra on Opera ng Company (2015), a case arising under a gas sales of the arbitra on being in London (which leads to the English Arbi- agreement rela ng to the Andrew Field in the North Sea. tra on Act applying). Nonetheless, Eder J found that the word THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 7 .

A case of two limbs able contract the following week. When reviewing damages for breach of contract, one usually starts about 160 years ago with the famous decision in Hadley v Baxendale [1854] EWHC Exch J70. The general rule is that damag- Economic or ï¬nancial loss can be within either limb es are meant to compensate the innocent party for the bargain it Economic or ï¬nancial loss is o en equated with the no on of lost, by pu ng it into the posi on it would have been if the con- ‘consequen al loss’. Over the years, there have been a number of tract had been performed. Damages for breach of contract can be decisions, including by the Court of Appeal, which have held that awarded for any loss that falls within the contempla on of the under English law ‘consequen al loss’ however means ‘indirect par es.

Hadley v Baxendale has divided recoverable losses into loss’ falling within the second limb of Hadley v Baxendale (see for two categories, or limbs: direct and indirect loss. instance Croudace Construc on v Cawoods 8 BLR 20, and Bri sh Sugar Plc v Nei Power Projects Ltd [1997] EWCA Civ 2438). Refer- Direct losses ring to ‘consequen al loss’ in an exclusion clause does not, there- As a ma er of law, all losses that occur as a direct, ordinary or fore, shed any light on what kind of economic or ï¬nancial loss, or natural consequence of the breach - or, to put it differently, which loss of proï¬t or revenue, has been excluded. All these types of arise in the usual course of things - are deemed to be reasonably monetary losses can either be direct, or indirect (‘consequen al’). foreseeable, and within the contempla on of the par es.

That Taking the Victoria Laundry case as an example, damages would be means the par es are objec vely taken to have foreseen that par- recoverable for all loss of proï¬t that would follow in the ordinary cular loss at the me of entering into the contract, whether or course of business, by the laundry not being able to serve custom- not they actually did. These ‘direct losses’ are o en referred to as ers without the delayed boiler. Certainly, loss of proï¬t that could coming within the ï¬rst limb of the rule in Hadley v Baxendale, and have been earned as a result of the performance of the contract they generally have to be ‘not unlikely’ (and hence reasonably itself is likely to be direct loss (see Hotel Services Ltd v Hilton Inter- foreseeable) to be recoverable (see Koufos v C Czarnikow Ltd (The na onal Hotels (UK) Ltd [1997] EWCA Civ 1822). Heron II) [1969] 1 AC 350). The decision in McCain Foods (GB) Ltd v Eco-Tec (Europe) Ltd [2011] EWHC 66 further illustrates that liability for direct ï¬nancial Special or indirect losses loss (within the ï¬rst limb) can be signiï¬cant.

McCain operated a But there may be other, more unusual and generally more ex- waste water treatment system, which produced biogas. It then tensive, losses that do not fall within the ï¬rst limb, but for which bought a system from Eco-Tec that was meant to generate electric- damages are nevertheless recoverable because these losses are ity from biogas. The system was, however, unï¬t for its purpose foreseeable in the par cular circumstances of the case, and hence and could not be installed and commissioned.

The contract exclud- not ‘too remote’. That, however, requires that the special circum- ed any liability for “indirect, special, incidental and consequen al stances which give rise to these losses were in fact brought within damages”. Nonetheless, the Court found that McCain could recov- the contempla on of the par es, for instance by having been com- er for all of the following ï¬nancial loss as a direct consequence of municated, or otherwise become apparent, at the me of contrac ng. The example that is o en used to illustrate this ‘second limb’ of Hadley v Baxendale is found in Victoria Laundry (Windsor) v Newman Industries [1949] 2 K.B.

528. The defendant seriously delayed the breach: • the cost of buying and installing a working replacement system to generate electricity from biogas; • the cost of buying electricity instead of genera ng it from the me that the system should have been opera onal; delivery of a new boiler for the claimant’s laundry business. As a • loss of revenue from opera ng the system, in par cular revenue result, the claimant lost considerable business, including an espe- that could have been earned by selling Cer ï¬cates of Renewa- cially lucra ve Government contract.

The Court of Appeal held ble Energy Produc on; that the loss of proï¬t under the Government contract was not • the addi onal cost of employing contractors, site mangers and recoverable. The defendant had neither been told about this deal, health and safety personnel while the system was being worked nor could he reasonably have expected to have known about it, on; and when signing the agreement. The other party has to be made • the cost of personnel already employed whose me was taken aware of any special circumstances at the me of entering into the up by the defects, the cost of expert analysis and tes ng, and contract.

That is the temporal cut off point (as reaffirmed, for in- the cost of addi onal equipment and further construc on work stance, by the House of Lords in Jackson v Royal Bank of Scotland purchased from Eco-Tec and others in an a empt to get the [2005] UKHL 3). So, things would have been different if Victoria system to work. Laundry had said ‘You do realise we might lose the deal of the century if you are very late with this boiler’ when signing the agreement - but not if they had only remembered to men on the proï¬t8 THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 All of this was found to be loss that resulted in the ordinary course from the failure to provide a working system. . A new considera on: the ‘assump on of responsibility’ for par cular losses The law as to what damages were recoverable for breach of longer the end of the ma er: one may now also ask whether it is commercially reasonable that they should be taken to have ‘accepted the risk’. contract had changed li le since Hadley v Baxendale un l 2008, In Transï¬eld itself, Lord Hope pointed out that a party to a con- when the House of Lords decided Transï¬eld Shipping Inc v Merca- tract who wishes to protect itself from a par cular risk can always tor Shipping Inc [2008] UKHL 48. In Transï¬eld, their Lordships con- draw the other party’s a en on to it - thus bringing it within their sidered the policy reasons behind the law on damages, iden fying contempla on. If the other party does not wish to assume respon- an assump on of responsibility (by the contrac ng par es) as the sibility for that risk, they can then ask for an appropriate exclusion. basis on which liability for losses of a par cular kind was imposed. His Lordship noted that the charterer in Transï¬eld could not be Transï¬eld concerned the late redelivery of a vessel by the charter- expected to assume responsibility for something they did not con- ers to the owners. The owners were forced to renego ate the trol, and knew nothing about, and for which he could not therefore subsequent charter, since the vessel could not be tendered on the quan fy the exposure.

It was not enough for the charterer “… to agreed date. The market was excep onally vola le during that know in general and on open-ended terms that there is likely to be a period, and the renego a ons led to a much lower rate than had follow-on ï¬xture.” On this approach, the owners could never have previously been agreed, based on the prevailing market price at provided the relevant informa on at the me of entering into the that me (which seemed to have fallen by 20 per cent over a few original charter, because they too had no idea by how much they days). would lose out subsequently when the market fell and they had to An arbitral tribunal found that all the losses incurred by the own- accept a lower rate. This does seem to go against previous deci- ers as a consequence of having to renego ate the subsequent ï¬x- sions to the effect that it was sufficient that the type of the loss was ture had been reasonably foreseeable.

The House of Lords, howev- foreseeable, but not the extent of the loss (Hill v Ashington Pigger- er, disagreed, and in so doing reformulated the test for remote- ies [1969] 3 All ER 1496), the detail of it, or manner in which it came ness. Lord Hoffman in par cular stressed that damages are award- about (Parsons (H) (Livestock) Ltd v U ley, Ingham & Co Ltd [1978] ed not purely based on what losses a reasonable person could fore- QB 791). see, but only for those losses for which the contrac ng par es nature of contracts). A signiï¬cant factor in this case was the very Unlikely loss may be recoverable if preven ng it falls within a contractual duty widespread acceptance or prac ce in the shipping industry that One way of explaining Transï¬eld is to treat it as being concerned charterers did not assume the full risk of the owner losing out on with an excep onally large loss, caused by the highly vola le and subsequent ï¬xtures if they delayed redelivery: charterers instead unpredictable market at the me, that was simply unforeseeable would have ‘assumed responsibility’ (reflec ng the consensual only expected to pay the difference between their charter rate and by either owner or charter and could never have been brought the market rate (if any) during the period of delay.

It followed that within the contempla on of the par es. However, subsequent the en re loss arising under the less favourable follow-on ï¬xture decisions have shown that Transï¬eld did introduce a new legal was not loss for which the charterers could be deemed to have principle, and was not just limited to its par cular facts. In Su- assumed responsibility at the me of contrac ng. pershield v Siemens, applying the ‘assump on of responsibility’ test Transï¬eld Shipping gave rise to some debate, not least because had the opposite result and led to a party being liable for damages the ï¬ve Law Lords expressed themselves in different ways, and not for loss that was unforeseeable, or unlikely.

The Court of Appeal all of them seemed to expressly endorse the ‘assump on of re- held that: sponsibility’ test. The Court of Appeal provided some guidance two years later, conï¬rming that assump on of responsibility was now part of the law, in Supershield Ltd v Siemens Building Technologies FE Ltd [2010] EWCA Civ 7. Toulson LJ explained that while Hadley v Baxendale remained the standard rule: “… Transï¬eld Shipping [is] authority that there may be cases where the court, on examining the contract and the commercial background, decides that the standard approach would not reflect the expecta on or inten on reasonably to be imputed to the par es.” “… logically the same principle may have an inclusionary effect.

If, on the proper analysis of the contract against its commercial background, the loss was within the scope of the duty, it cannot be regarded as too remote, even if it would not have occurred in ordinary circumstances.” The case concerned a flood in an office building caused by a sprinkler system. A ball valve and drains were both aimed at preven ng such a flood. The evidence showed that this was an unlikely, possibly unprecedented, failure of both these protec on measures.

The Court of Appeal noted that such unlikely loss would This introduces a further element of judicial discre on into the s ll be recoverable if it came within a contractual duty to prevent it recoverability of damages. Whether the par es may have contem- from occurring. In complex projects, designers may well incorpo- plated a par cular loss when they entered into the agreement is no rate several redundant protec on or ‘failsafe’ measures, but it THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 9 .

would be no excuse to say that the circumstances in which they all blush) the LOGIC form appears to favour the drilling contractor. failed were unlikely - if it was the duty of the designers to protect Transocean’s ï¬rst argument was that Providence had to pay the against flooding, ï¬re or the like. The Court of Appeal held that: “If … the unlikely happens, it should be no answer for one of them to say that the occurrence was unlikely, when it was that party’s responsibility to see that it did not occur. … the reason for having a number of precau onary measures is for them to serve as a mutual back up, and it would be a perverse result if the greater the number of precau onary measures, the less the legal remedy available to the vic m in the case of mul ple failures.” applicable day rates (based on the par cular ac vity of the rig on any given day) irrespec ve of whether the BOP problems were Transocean’s fault under the contract. It pointed to a number of speciï¬ed rates (all close to US$ 250,000 per day) that were said to be payable even if the rig happened to be doing something that could be the result of Transocean’s negligence - examples being the ‘redrill rate’ or the ‘ï¬shing rate’ (which applies when some object has fallen into the well bore and has to be retrieved). Counsel for Transocean argued that a risk alloca on that was not fault-based made sense: failures affect drilling opera ons are Liability for economic or ï¬nancial loss will also be assessed un- o en technically complex, and can require lengthy inves ga ons der the above principles.

What is more, contractual provisions to determine the cause of the failure, and whether any breaches of seeking to preclude or limit liability for any types of losses that are the drilling contractor’s obliga ons or standards of performance recoverable in principle will be treated as ‘exclusion clauses’, and might be involved. Transocean said that the simple alloca on of they will be construed strictly, as can be seen from the two recent risk provided for by its reading of the remunera on clause as a decisions in Transocean v Providence and Sco sh Power v BP Ex- complete code gave everyone clarity and certainty: one could not plora on Opera ng Company. expect expensive drilling opera ons to grind to a halt, with support services and third par es all having been mobilised, while the par- Transocean Drilling UK Ltd v Providence Resources Plc [2014] EWHC 4260 es went off to the Commercial Court or an arbitral tribunal to ï¬nd out who was to blame. The decision of the Commercial Court in Transocean Drilling UK Mr Jus ce Popplewell disagreed. He referred to three principles Ltd v Providence Resources Plc [2014] EWHC 4260 (Comm) shows or proposi ons of English contract law that could only be displaced that contractors relying on apparently comprehensively dra ed by very clear words in the contract: exclusion and limita on clauses in industry standard form con- • ï¬rstly ,that a party to a contract should not be able to take ad- tracts may nonetheless be in for an unwelcome surprise if they fail vantage of, or beneï¬t from, its own breach (found in Alghussein to perform to the contractual standard. Establishment v Eton College [1988] 1 WLR 587); Transocean had agreed to provide a semi-submersible drilling • secondly, that exemp on clauses which could be taken on their rig, the ‘Ar c III’ to Providence, under a drilling contract based on face to refer only to non-negligent breaches will be so con- the LOGIC form.

The Ar c III was to drill an appraisal well in the strued, unless a very clear inten on to extend their scope to Barryroe Field, located in the Cel c Sea south of Cork, Ireland. negligence is apparent; and Transocean’s remunera on provisions in the drilling contract pro- • thirdly, that when construing a contract “… one starts with the vided for a daily opera ng rate of US$ 250,000, with slightly lower presump on that neither party intends to abandon any reme- rates for wai ng on instruc ons and repair (the la er being US$ dies for its breach arising by opera on of law, and clear ex- 245,000 per day). press words must be used in order to rebut this presump- Drilling was delayed for 46 days, between 18 December 2011 and 2 February 2012, due to problems caused by the blow-out on.” (Gilbert-Ash (Northern) Ltd v Modern Engineering (Bristol) Ltd [1974] AC 689). preventer (“BOP”) stack. While the BOP problems prevented drill- Following on from the third principle, it is a fundamental right, ing, Providence incurred substan al marine spread costs - being recognised by the common law, that a buyer does not have to pay the daily rates payable to all the other contractors providing sup- for defec ve, or deï¬cient, goods and services - this is the venera- port services for the drilling opera ons (Providence was responsi- ble remedy of ‘abatement’ which ul mately allowed Providence to ble for well logging, tes ng, cemen ng, mud engineering and log- defeat Transocean’s claim. ging, geological services, casings, direc onal drilling, diving and The judge also relied on a previous Court of Appeal decision, in ROVs). Providence’s spread losses came to about US$ 10 million. Sonat Offshore SA v Amerada Hess [1998] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 145, con- Transocean commenced the li ga on, claiming unpaid sums under cerning another rig, which had suffered a ï¬re due to lack of the drilling including approximately US$ 7.6 million calculated maintenance by the owner.

The Court of Appeal held that that based on day rates for the period of the delays. Providence resist- contract, too, did not amount to an agreement that ‘something ed that claim, and counterclaimed for its spread losses. would be paid for nothing’, and that an obliga on to pay during a Standing in Transocean’s shoes at the outset of the proceedings, one might have felt fairly conï¬dent because (certainly at ï¬rst 10 period when no services were performed would only be implied absent any other reasonable alterna ve. The manner in which THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 .

Parker LJ phrased the ques on in Sonat illustrates how English contract law approaches the issue: judge found, simply could not have been intended. The judge went on to ï¬nd that the BOP problems had been “[The main issue] is whether the company, having been deprived caused by breaches of contract, on the part of Transocean, largely of all beneï¬t from the rig for one month due to the negligence and by reason of poor maintenance. At the me, Transocean had car- breach of contract of the contractor, is nevertheless obliged to pay, ried out an internal inves ga on into the causes of the relevant during that period, the equipment breakdown rate without any failures, on the understanding that Providence would be supplied right of reduc on, set-off or counterclaim. Unless the terms of the with a copy of the resul ng report. Unhappily for Transocean, ini- agreement are such as to exclude such a right, the company is al dra s that iden ï¬ed lack of proper maintenance of BOP ele- clearly not so obliged.” ments as the root cause were ‘doctored’, and any references to It can be seen that it is the purchaser’s right not to pay when no inadequate maintenance were removed, before Providence was services are being performed, and it is that right that needs to be given the report.

Popplewell J noted that this amounted to decep- given up, or excluded. A clause merely referring to rates being payable in circumstances that might or might not involve a period on which “reflect[ed] no credit on Transocean's senior management”. without services or delays due to negligence may very well fall short of having that exclusionary effect. This is even more likely the result where the remunera on provision in ques on is expressed Was Providence’s spread loss excluded by virtue of being ‘Consequen al Loss’? to be in return for the provision of services, rather than being ex- Transocean’s breach in turn en tled Providence to rely on abate- pressed purely by reference to periods of me elapsed under the ment as a defence to Transocean’s claim for payment.

Of course, contract. Providence also wanted to recover the US$ 10 million in spread Popplewell J also expressly stated that a rig contract was no costs that it had incurred. The obstacle to overcome in that en- different from any other contract for goods and services. Drilling deavour was Clause 20, which excluded liability for ‘Consequen al contractors or operators some mes rely on the inherent risk in Loss’ (as deï¬ned) and provided for knock-for-knock indemni es as offshore explora on works, or the ‘knock-for-knock’ indemni es regards such losses affec ng the property, equipment and so on of which provide that each party is responsible for loss of or damage Providence and Transocean respec vely. to their own equipment and personnel, even though that may have Breaking the clause down into its cons tuent parts, the ï¬rst limb been caused by the negligence of the other party, sta ng that of the deï¬ni on of Consequen al Loss referred to “(i) any indirect these contracts are ‘special’.

They are not, and fall to be construed or consequen al loss or damages under English law.” This was a just like an ordinary agreement for the hire of a car: reference to the second limb in Hadley Baxendale, meaning losses “… hirers of a rig are no more likely than any other person who contracts for the provision of goods and services to agree to pay something for nothing, par cularly if the failure to perform is due to the negligence or default of the payee .” that did not result in the ordinary course of things as a direct consequence of the breach, and which would only be recoverable if the special circumstances that gave rise to the relevant loss were within the contempla on of the par es. The par es were agreed that Providence’s spread losses were direct losses, and hence not One key provision that Transocean was relying on was the repair rate clause: “3.9 Repair Rate $245,000 Except as otherwise provided, the Repair Rate will apply in caught under this heading. The next part of the deï¬ni on of Consequen al Loss sought to widen the concept to certain direct losses (under the ï¬rst limb), and was so widely dra ed that it might - on a cursory read - be thought to capture Providence’s spread loss: the event of any failure of [Transocean's] equipment “(ii) to the extent not covered by (i) above, loss or deferment (including without limita on, non-rou ne inspec on, repair of produc on, loss of product, loss of use (including, without and replacement which results in shutdown of opera ons limita on, loss of use or the cost of use of property, equip- under this CONTRACT …” ment, materials and services including without limita on, The judge found that the reference to the rate being payable regardless of “any failure” of Transocean’s equipment did not mean that Providence had agreed to pay Transocean when the rig was not performing the required work because of a breach by Transocean. “Any failure” really meant ‘a failure for which Transocean was not responsible under the contract’.

Indeed, if Transocean were right, Transocean would have to be paid if it deliberately sabotaged the rig and then claimed the repair rate, and that, the those provided by contractors or subcontractors of every er or by third par es), loss of business and business interrup on, loss of revenue (which for the avoidance of doubt shall not include payments due to [Transocean] by way of remuneraon under this CONTRACT), loss of proï¬t or an cipated proï¬t, loss and/or deferral of drilling rights and/or loss, restric on or forfeiture of licence, concession or ï¬eld interests …” The above was the cri cal wording on which Transocean’s case THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 11 . rested. Once again, the Court applied the principle in Gilbert-Ash, that commercial par es (even those entering into a rig contract, with all the a endant risk and exposure) were unlikely to give up their basic rights at common law - and the right to recover damages for direct losses flowing from a breach of contract is such an en tlement. The judge held that sub-paragraph (ii): The Court further noted that: "Cost of use … is an example given within the parenthesis of a loss of use. It covers the cost of hiring in equipment or services, or replacing property the beneï¬t of which has been lost, in order to mi gate the loss of beneï¬t. It has no applicaon to the spread costs where the costs are for equipment and services which were provided.

Providence did not lose “must be construed in the context of it being a speciï¬cally the use of that equipment or those services, which remained deï¬ned incursion into the territory of the ï¬rst limb of Hadley available to it, which is why Providence incurred wasted ex- v Baxendale, and should therefore be approached by trea ng penditure in paying for them.” the enumerated types of loss as incremental incursions into that territory, construed narrowly to limit the scope to speciï¬c categories narrowly deï¬ned rather than a widespread redeï¬ni on of excluded loss.” Finally, and picking up the thread running through the judgment, Popplewell J noted that if Transocean’s reading were right, then the exclusion would cover each and every kind of loss that Providence might conceivably suffer. English law does not easily accept The fact that there was a mutual indemnity regime (knock-for- such a result in a commercial contract. As the House of Lords not- knock) in the contract did not displace that assump on, as the ed in Suisse Atlan que Societe d'Armement Mari me SA v NV Court of Appeal had noted in EE Caledonia Ltd v Orbit Valve Co Ro erdamsche Kolen Centrale [1967] 1 AC 361 Europe Plc [1994] 1 WLR 1515. Stacking the odds further against Transocean was the “contra proferentem” rule of contractual interpreta on, which provides that exclusion clauses are to be interpreted narrowly and against the party seeking to rely on them. Returning to the contract wording, eight different types of loss were enumerated in the clause: (i) loss or deferment of produc on; “… the par es cannot, in a contract, have contemplated that the clause should have so wide an ambit as in effect to deprive one party’s s pula ons of all contractual force; to do so would be to reduce the contract to a mere declara on of intent.” Transocean lost because the judge felt that the dra ing in the LOGIC form, whilst certainly effusive, was not actually wide enough to cover the spread cost.

It is at least plausible, if not likely, that a (ii) loss of product; (iii) loss of use (including, without limita on, loss of use or the contrary result was intended by the dra er, and that industry play- cost of use of property, equipment, materials and services ers had been opera ng on the assump on that such a result had including without limita on, those provided by contractors or been achieved. Not so. subcontractors of every er or by third par es); (iv) loss of business and business interrup on; (v) loss of revenue; Sco sh Power UK Plc v BP Explora on Opera ng Company Ltd [2015] EWHC 2658 (vi) loss of proï¬t or an cipated proï¬t; In late September 2015, the Commercial Court had a further (vii) loss/deferral of drilling rights; and opportunity to construe an exclusion clause concerned with conse- (viii) loss/restric on/forfeiture of licence, concession or ï¬eld inter- quen al loss, in a long term gas sales agreement. Sco sh Power ests. had contracted to buy natural gas under a series of virtually iden - The Court found that all these types of loss were concerned with cal agreements with the owners of the Andrew Field in the North losing income or revenue that would have been generated but for Sea.

The Andrew owners had shut down produc on for about the breach. Spread costs fall into a different category - as they are three and half years, from May 2011 to December 2014. The shut- costs incurred for (usually) plant and equipment that is on hire, but down was required to allow for works to e in the Andrew facili es cannot be ‘used’ effec vely. with the neighbouring Kinnoull Field.

The Commercial Court found Transocean however argued that the spread costs claim was for ‘loss of use of the property, equipment, materials and services it was a breach of the gas sales agreement. During the shutdown period, Sco sh Power had con nued to provided by contractors, subcontractors and third par es’, and so make daily nomina ons for quan squarely within the excluded category of loss at item (iii) above. would be delivered), and had gone into the market to purchase The judge did not accept that. He concluded that ‘loss of use’, replacement gas, at a price greater than that which would have when looked at together with its contractual neighbours (all con- applied under the gas sales agreements with the Andrew owners. es of gas (even though nothing cerned with loss of revenue), was more naturally to be read as “… or remedy, whereby the Andrew owners were required to deliver the use of property or equipment.” 12 These agreements also provided for a par cular contractual regime conno ng the loss of expected proï¬t or beneï¬t to be derived from an equivalent quan ty of so-called Default Gas at a lower price, THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 . sold itself. Business interrup on was similar in nature. once produc on and deliveries had resumed, to make up for the shor all. (iv) Finally, loss of use was also concerned with a secondary loss, which might result from Sco sh Power being unable to use Sco sh Power claimed damages based on the addi onal cost of the gas it had contracted for in its own business. having to buy replacement gas, whilst giving credit for the value of Default Gas that would be provided by the sellers under the contract. All these losses were of a kind that went beyond the basic measure, and were concerned with future beneï¬ts that could be earned Mr Jus ce Legga decided a number of preliminary issues, one if the contract had been performed (so indirect losses), not with being whether such a claim for damages would be excluded by the cost of replacing the very same goods that had been promised Ar cle 4.6 of the agreements, which provided: under the contract. “Save as expressly provided elsewhere in this Agreement, neither Party shall be liable to the other Party for any loss of use, proï¬ts, contracts, produc on or revenue or for business interrup on howsoever caused and even where the same is caused by the negligence or breach of duty of the other Party.” The Andrew owners claimed that this precluded a claim for the The Andrew owners however also raised another point, arguing that losses incurred in mi ga ng an excluded type of loss were themselves also excluded. Hence, since Sco sh Power could not have claimed for losses rela ng to other contracts (such as loss of proï¬ts) that it intended to fulï¬ll with the (more expensive) replacement gas, then (it was submi ed) neither could Sco sh Power claim for the addi onal cost of purchasing that replacement gas that was going to be used to perform those other contracts. addi onal cost incurred in procuring replacement gas in the open Legga J held that there was no principle of law that required a market. Legga J gave this argument short shri , describing it as loss incurred in mi ga ng an excluded loss as also being (itself) an untenable conten on.

As in Transocean, he had in mind the excluded. He noted that if this argument worked, one would not principle in Gilbert-Ash - that par es do not easily give up the en - ï¬nd it very difficult to exclude a great many (direct) losses, because tlement or remedy they have at law (though in the end found it they would have been incurred in the a empt to mi gate other unnecessary to even bring it into play). Damages for a failure to (indirect) losses.

But this rela onship of mi ga on did not mean deliver in a contract for the sale of goods would in the ordinary that a clause that was concerned with indirect losses could, as if by course be assessed under the Sale of Goods Act 1979. Sec on 51 magic, also apply to direct losses. (2) provides that the measure of damages is “the es mated loss The Andrew owners relied on a judgment by Rix J in BHP Petrole- directly and naturally resul ng, in the ordinary course of events, um Ltd v Bri sh Steel plc [1999] 2 All ER (Comm) 544, where he said from the seller’s breach of contract”, while subsec on (3) goes on that: to provide that if there is an available market, the loss is taken to be the difference between the contract price and the market price for the goods at the me the goods were meant to have been delivered. Ar cle 4.6 did not seek to draw a dis nc on between direct and indirect loss, and did not make reference to ‘consequen al loss’. Instead, it referred to types of loss. One may assume that the inten on behind the clause was to exclude all losses that were of the “… in many instances losses are claimed on the basis of mi ga on; a greater loss of one kind is avoided by the incurring of a lesser loss of another kind in mi ga on of the ï¬rst.

In my judgment, such mi gated loss must be regarded as though it was, for the purpose of [the exclusion clause in ques on] a loss of the kind sought to be avoided …” BHP v Bri sh Steel concerned a failed pipeline that had to be relevant types listed out, regardless of whether they were direct, replaced. The contract provided that Bri sh Steel was not liable for or indirect. The loss that Sco sh Power sought to recover was “loss of produc on”.

Legga certainly ‘direct’, as is apparent from the Sale of Goods Act, but lowed to recover the cost of replacing the pipeline itself (a direct was it of the requisite (excluded) type? The judgment gives a brief loss, like Sco sh Power’s cost of replacing the gas), whilst it had commentary on how these types were construed by the Court: been unable to recover certain addi onal costs in producing oil and (i) Loss of proï¬ts concerns the situa on where Sco sh Power gas that had resulted from the pipeline failure: that was ‘loss of was unable to resell gas at a proï¬t. Loss of revenue was simi- produc on’, even though these costs may have been incurred in lar. order to mi gate the loss, by (for example) restoring produc on (ii) Loss of contracts applied to any agreements that might be J explained that BHP had been al- sooner rather than later. cancelled, or opportuni es to enter into new agreements that Sco sh Power lost, because it did not have the gas promised by the Andrew owners. The Sole Remedies Clause So far, so good for Sco sh Power: the loss incurred in buying (iii) Loss of produc on referred to any inability to produce other the more expensive replacement gas was not excluded. However, products - such as electricity - because there was no gas from the gas sales agreement also included a ‘sole remedy’ provision the Andrew Field, but it was not aimed at the gas that was that referred to the supply of Default Gas at the agreed, reduced THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 13 .

price as being the only redress for the buyer. Ar cle 16.6, the key clause, stated: Discussion It has to be recalled that when it comes to the interpreta on of “The delivery of Natural Gas at the Default Gas Price and the payment of the sums due in accordance with the provisions of Clause 16.4 shall be in full sa sfac on and discharge of all rights, remedies and claims howsoever arising whether in contract or in tort or otherwise in law on the part of the Buyer against the Seller in respect of underdeliveries by the Seller under this Agreement, and save for the rights and remedies set out in Clauses 16.1 to 16.5 (inclusive) and any claims arising pursuant thereto, the Buyer shall have no right or remedy and shall not be en tled to make any claims in respect of any such underdelivery.” contracts, each case will depend on the words used in the par cular contract, interpreted in the usual way (so objec vely and in the light of the factual background and the commercial purpose of the transac on). Strictly speaking, it is possible that expressions such as ‘consequen al loss’, ‘loss of use’ or ‘loss of produc on’ might be given different interpreta ons where they appear in different agreements. In prac ce, however, this is unlikely: for one thing, decisions interpre ng these par cular expressions are o en cited as Transocean was cited in Sco sh Power. Following the decisions of Popplewell J and Legga J (and further authori es they both rely on in their judgments), one can iden fy certain points or approaches to construc on which are Legga J upheld that clause (widely dra ed as it was) as exclud- likely to feature in subsequent cases dealing with similar clauses: ing Sco sh Power’s claim for anything other than delivery of De- • High-value, complex agreements in the energy industry (be they fault Gas at the agreed discount, since Sco sh Power’s claim was rig hire or drilling contracts or long term gas sales agreements) in ‘respect of underdeliveries’.

The gas sales agreement required are not exempt from basic principles of construc on: no com- Sco sh Power to con nue to make daily nomina ons even during mercial party is easily presumed to have agreed to pay some- the period of the shutdown, and any shor all in deliveries against thing for nothing, and basic rights and remedies at common law nomina ons were in effect ‘underdeliveries’ (and hence within must be expressly excluded. Ar cle 16.6). The judge found it did not ma er that this clause • The reported decisions suggest that expressions such as ‘loss of could enable the Andrew ï¬eld owners to breach the contract delib- use’, ‘cost of use’ or ‘loss of produc on’ may well be taken to erately, by selling gas to someone other than Sco sh Power at a refer to indirect losses, within the second limb of Hadley v higher price, and inten onally causing an underdelivery. Baxendale, and, to the extent that a clause tries to make inroads The judgment provides a neat reminder that an award of damag- into the recoverability of direct losses that fall within the ï¬rst es or compensa on under English contract law is not concerned limb of Hadley v Baxendale, such a provision will be construed with punishing the contract-breaker for any fault or wrongdoing: narrowly. This is illustrated by Transocean v Providence. “It is a basic principle that the object of an award of damages for breach of contract is to compensate the claimant for loss sustained as a result of the defendant’s breach and not to deprive the defendant of any gain.

Moreover, this principle applies and the measure of damages is the same irrespec ve of whether the breach was deliberate, careless or en rely innocent. I see no reason to infer that the contractual remedy with which the remedy of damages is replaced by Ar cle 16 was intended to operate differently.” • It may serve par es well to consider abandoning some of these phrases o en found in exclusion or limita on clauses, and say more plainly what they mean by reference to the par cular transac on: if everyone agrees that the cost of keeping support services and logis cs (including the marine spread) mobilised while a drilling is non-produc ve, then say precisely that in the contract. • Although clear words are needed to exclude the ordinary remedies that the law provides, it is s ll necessary to keep a cool head and not be influenced by perceived ‘bad behaviour’ (or One limit of Ar cle 16, however, would have been a claim for deliberate breaches) by any party. A contract breaker is gener- damages for repudiatory breach (i.e.

a serious breach that went to ally free to make gains, provided that the innocent party is com- the root of the bargain between the par es). If the sellers deliber- pensated for its (recoverable) losses. ately decided to shut down the produc on facili es for good, or In conclusion, if the alloca on of risks or liabili es is really in- without any kind of commitment to resume produc on at some tended to favour one party in par cular, then you need to be very point in the future, that breach might en tle Sco sh Power to careful to spell this out, and (ideally) explain why this has been terminate the contract by accep ng the Andrew ï¬eld owners’ repu- agreed in the contractual wording. A judge or arbitrator, who diatory breach.

A sole remedies clause could not then save the comes to the agreement cold some years later, might otherwise sellers from a claim for damages based on the cost of obtaining all apply the principles of construc on discussed in this ar cle to gas that should have been delivered over the remaining term of the achieve a different, more balanced, result. ï‚¥ contract, at the market price. But that was not the situa on, as the Andrew ï¬eld owners had no such intent. 14 THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 .

Winter is Coming: The Expanding Deï¬ni on of Assets in Freezing Injunc ons on a huge scale”, consis ng of dozens of claims and counterclaims between Ablyazov and BTA. One of the earliest applica ons made by BTA was for a worldwide freezing order (“WFO”) over Mr Ablyazov’s assets. BTA argued that there was a real risk that Ablyazov would dissipate his assets before any judgment in their favour could be enforced. Mr Jus ce Blair agreed with BTA and, in August 2009, ordered a WFO in the by Ryan Deane In the recent case of JSC BTA Bank v Ablyazov [2015] UKSC 64, the UK Supreme Court has following terms: “4. Un l judgment or further order … the respondent must given important guidance on the scope of the not, except with the prior wri en consent of the Bank's solici- standard form of freezing order issued by the tors – English courts. a.

Remove from England and Wales any of his assets which Background are in England and Wales … up to the value of £451,130,000 Muktar Ablyazov was once a member of the … poli cal elite in Kazakhstan and a protégé of its president, Nursultan Nazarbayev. In 1998 he was appointed to the coveted post of b. In any way dispose of, deal with or diminish the value of Minister of Energy, Industry and Trade.

He used his posi on of any of his assets in England and Wales up to the value of … influence to secure favourable business deals, including the acquisi- £451,130,000 … on of shares in Bank TuranAlem, which later came to be known as BTA Bank (“BTA”). c. In any way dispose of, deal with or diminish the value of In late 2001, Ablyazov broke ranks with Nazarbayev’s ruling par- any of his assets outside England and Wales unless the total ty, ci ng disenchantment with corrup on in the president’s inner unencumbered value … of all his assets in England and Wales circle. He co-founded an opposi on movement, Democra c Choice … exceeds £451,130,000 … of Kazakhstan, to challenge the Nazarbayev regime.

It was not long before Ablyazov was arrested. The charge was ‘abusing official 5. Paragraph 4 applies to all the respondents’ assets whether powers as a minister’.

Unsurprisingly, the arrest was deemed by or not they are in their own name and whether they are solely Amnesty Interna onal and the European Parliament to be or jointly owned and whether or not the respondent asserts a ‘poli cally mo vated’. beneï¬cial interest in them. For the purpose of this Order the Ablyazov was convicted and sentenced to six years in prison, respondents’ assets include any asset which they have power, where he alleged that he was subjected to regular bea ngs and directly or indirectly, to dispose of, or deal with as if it were torture, but was released a er only ten months on the condi on their own. The respondents are to be regarded as having such that he renounce poli cs.

On his release from prison, however, power if a third party holds or controls the assets in accord- Ablyazov con nued to fund independent media and poli cal groups ance with their direct or indirect instruc ons.” opposed to Nazarbayev. He used his new-found freedom to reestablish es with BTA, and in 2005 became its chairman. He held this posi on un l early 2009, when BTA execu ves accused him of illicitly transferring vast sums of money from the bank to companies beneï¬cially owned by him.

Kazakhstan’s sovereign wealth fund, Samruk-Kazyna, subsequently injected signiï¬cant funds into BTA and became the majority shareholder, effec vely na onalising the bank. Ablyazov claimed that the allega ons and the state’s takeover of BTA were all part of Nazarbayev’s plan to ruin him by any means possible. Fearing being put on trial again in Kazakhstan, Ablyazov fled to England, where he had substan al assets, including a property in North London on The Bishop’s Avenue (known as “Billionaire’s Row”), and a 100 acre country estate in Surrey. In March 2009, BTA commenced proceedings in the English High Court to recover the The WFO contained a standard excep on to these terms, namely that Ablyazov was permi ed to spend a reasonable amount on legal representa on and a ï¬xed amount on “ordinary living expenses”.

It is some indica on of Ablyazov’s wealth that the court deemed his ordinary living expenses to be £10,000 per week. Shortly a er the WFO was issued, Ablyazov entered into two loan facility agreements with a BVI company called Wintrop Services Limited (“Wintrop”) and a further two agreements, in materially the same terms, with another BVI company called Fitcherly Holdings Limited (“Fitcherly”), (collec vely, “the Loan Agreements”). Each of the Loan Agreements provided for a facility of £10 million to be made available to Ablyazov. The terms of the Loan Agreements were highly favourable to Ablyazov: he was not required to provide security for the loans (which would be ‘dealing’ with his assets within the meaning of the WFO) and the lenders assets Ablyazov had allegedly misappropriated.

This marked the beginning of what one judge described as “extraordinary li ga on THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 15 . were not en tled to demand repayment un l four years a er the before the claimant’s claim was established. The defendant would commencement of the facility. therefore in effect be allowed to make payments out of his assets Ablyazov subsequently drew down the full amount of £40 million without regard to the restric ons imposed on him by the WFO. allowed by the Loan Agreements, direc ng that Wintrop and Fitch- Ablyazov’s counter argument rested on direct legal authority. erly make the payments directly to various third par es. The major- Neuberger J, as he then was, in Cantor Index Ltd v Lister [2002] CP ity of the money was used to fund Ablyazov’s gargantuan legal bill. Rep 25, held that a defendant who borrows money increases his Payments were made to over ten leading counsel, more than 20 indebtedness but does not dispose of, deal with or diminish the juniors and to 75 other lawyers from at least eight different ï¬rms. value of his assets within the meaning of a freezing order. In re- Over £10 million was paid to one ï¬rm of solicitors alone: Christmas sponse to the argument that this approach would allow a defendant had certainly come early.

Smaller amounts (rela vely speaking) to in effect circumvent a freezing order by reducing his net asset were also used to pay various personal expenses, such as approxi- posi on, Neuberger J said the following (emphasis in original): mately £350,000 in connec on with Ablyazov‘s property on The Bishop’s Avenue. In 2012, BTA brought proceedings in the High Court seeking a declara on that Ablyazov’s rights under the Loan Agreements were “assets” within the meaning of the WFO. It would follow that Ablyazov had breached the WFO by spending more than a reasonable amount on legal representa on and more than £10,000 per week on living expenses. BTA also sought disclosure of all drawings made pursuant to the Loan Agreements to enable it to trace, and if possible recover, the proceeds. BTA’s primary posi on was that the Loan Agreements were a sham and that Ablyazov was in ul mate control of both Wintrop and Fitcherly.

Mr Jus ce Clarke, in related proceedings between BTA and Ablyazov, said that there was good reason to suppose that this was the case, but declined to decide the point on the basis that “I see the force of that submission as a ma er of good sense and prac cality. However I do not think that it is right, in light of the words of paragraphs 1(1) and 1(2) of the order. They provide that the defendant should not “dispose of, deal with or diminish the value of any of his assets”.

For a debtor to increase his indebtedness by borrowing from an exis ng creditor or even to create an indebtedness by borrowing from a new creditor, at least where the creditor is not secured on any of the debtor's assets, does not to my mind, as a ma er of ordinary language, involve disposing of or dealing with or diminishing the value of any of the debtor's assets . I accept that it results in a diminu on of the debtor's net asset posion, but that is not what paragraphs 1(1) and 1(2) of the Freezing Order refer to.” it had not been fully argued before him. Ablyazov maintained that BTA submi ed that Cantor Index could be dis nguished on the the loans were made to him by trusted friends and associates in facts because the freezing order Neuberger J was referring to did control of Wintrop and Fitcherly.

In any event, BTA was prepared not contain the extended deï¬ni on of ‘assets’ present in paragraph to accept for the purpose of the proceedings that the Loan Agree- 5 of the WFO. The deï¬ni on, it was argued, was wide enough to ments were validly entered into at arm’s length between commer- cover an intangible right which, if exercised, which would indirectly cial par es. diminish the value of a debtor’s assets. The Par es’ Arguments the posi on as it was under Cantor Index. The expanded deï¬ni on Ablyazov submi ed that the new wording made no difference to BTA put forward two arguments explaining why Mr Ablyazov’s was directed at a different situa on, namely where the asset in rights under the Loan Agreements were assets within the meaning ques on is held by a third party in circumstances where the re- of the WFO.

Its primary argument was that a right to borrow mon- spondent has the power to control the asset but may hold some- ey from a lender under a loan facility is a ‘chose in ac on’ (a proper- thing short of a legal or beneï¬cial tle (e.g. because he is a trustee ty right in something intangible) and English law has long classiï¬ed or nominee of the asset). Ablyazov argued that the expanded deï¬- choses in ac on as assets.

BTA’s secondary argument was that, if a ni on was aimed at clarifying what type of interest the respondent right to borrow money is not usually classiï¬ed as an asset in the must have in the property rather than the nature of the assets in context of a freezing order, the extended deï¬ni on of asset in para- which an interest may be had for the purposes of the freezing or- graph 5 of the WTO was broad enough to cover Ablyazov’s rights der. A right to borrow money under a loan facility was not an asset under the Loan Agreements. In either case, Ablyazov had ‘dealt’ within the meaning of the WFO because it was not something that with that asset by direc ng payments pursuant to the Loan Agree- could be diminished in value. ments to third par es. BTA argued that if the posi on were otherwise, a defendant Decision of the High Court subject to a WFO could borrow a large sum of money, thereby re- the right to borrow money was not to be regarded as an ‘asset’ reducing the amount available for the claimant by the full extent of within the meaning of the WFO.

The purpose of the WFO was to the loan if, say, the lender obtained a judgment for that amount 16 The judge, at ï¬rst instance, agreed with Ablyazov. He held that ducing his overall net asset posi on by that amount, and poten ally prevent Ablyazov from disposing of his assets so as to frustrate an THE ARBITER WINTER 2015 . a empt by BTA to enforce any future judgment it might secure crea vely evading their intended applica on. On the other hand, against him. It followed that the assets to which the WFO referred the third principle weighs in favour of a narrow, literal construc on are assets which could be of some value to BTA and against which because of the poten ally draconian effect of a freezing order on BTA would be capable of securing execu on. the economic freedom of an individual against whom no judgment The judge found the rights to borrow under the Loan Agreements had no monetary value that BTA could realise. There was no secondary market for such rights. has yet been granted. In applying these principles to the WFO over Ablyazov’s assets, The loan facility was non- Beatson LJ reiterated many of the points raised by the judge at ï¬rst assignable, and the lenders would have no incen ve to agree to instance.

In par cular, he emphasised that fact that the rights un- transfer the rights by nova on to BTA on the same favourable der the Loan Agreements had no value to BTA and therefore the terms as the original lending facility. Because Ablyazov’s rights had enforcement principle could not support their construc on of the no value to BTA, it could not have been intended that the exercise WFO. In summary he held that, applying the strict construc on of those rights should be subject to the WFO. principle, the words of the order were not clear enough to bring the The judge held that the extended deï¬ni on of assets in the WFO rights under the Loan Agreement within the remit of the WFO. did not change this posi on.

Ablyazov did not deal with any asset Addi onal words would need to be added to the standard form as if it was his own. He could only exercise his right to direct money freezing order for such rights to be deemed ‘assets’. to be paid under the loan facility. Un l the money reached the Neither did the expanded deï¬ni on of assets in paragraph 5 of payees, the lenders owned and controlled that asset and they alone the WFO assist BTA.

Beatson LJ agreed with Ablyazov that the pur- had the power to deal with it as their own. For these reasons, pose of the expanded deï¬ni on was to cover assets that were not BTA’s applica on was dismissed. beneï¬cially or legally owned by a defendant but over which he had control, for example in his capacity as a trustee or nominee. The Decision of the Court of Appeal control a trustee or nominee has over an asset is very different The Court of Appeal upheld the ï¬rst instance decision.

The lead- from the control that Ablyazov had over the money borrowed un- ing judgment was given by Beatson LJ, whose judgment focused on der the Loan Agreements. A strict construc on did not permit a three principles that he held were relevant to the construc on of a wider interpreta on of the expanded deï¬ni on in paragraph 5 in freezing order. circumstances where that deï¬ni on was clearly directed at a differ- The ï¬rst, and most important, of these was the ‘enforcement ent category of asset. principle’, which he expressed as follows: “the purpose of a freezing order is to stop the injuncted defendant dissipa ng or disposing of property which could be the subject of enforcement if the claimant goes on to win the case it has brought, and not to give the claimant security for his claim”. The second was the ‘flexibility principle’, namely: “the jurisdic on to make a freezing order should be exercised Decision of the Supreme Court In a short, 12 page judgment, the Supreme Court overturned the decisions of the High Court and the Court of Appeal. Lord Clarke, with whom Lords Neuberger, Mance, Kerr and Hodge agreed, began his judgment by no ng that BTA had, by this point, obtained a number of judgments against Ablyazov in the English courts, amoun ng to a total of $4.4 billion.