Description

ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENT SOLUTIONS

hedge fund ELEMENTS

Compensation Variables

The principals of ALPS have been actively engaged in the hedge fund industry since 1982 - the fledgling days of the new era

of hedge funds. Having managed funds, invested in them, kicked the tires on hundreds and administered hundreds more, you

might expect that we have some opinions. That is doubly true when it comes to manager compensation. That said, the postulate

that “there is nothing new under the sun” isn’t necessarily true in hedge fund land.

This discussion is intended to set forth our observations on the current state of the art. First of all, how many people can name a dozen managers who returned 17% gross over the last twenty years? In a “two and twenty” hedge fund (manager compensation of 2% of assets plus 20% of profits), 17% turns into 12% net – just about what the S&P 500 has returned in the 20 years since October 1987. That is not to say that hedge fund fees are not fair – just that investors often expect something else in addition to the returns; such as consistency, superior risk control or diminished or negative correlation with their other investments. The point is that compensation choices should be decided within the context of the fund’s expected style and investment profile. Currently, we see annual management fees ranging from about 0.5% to 2.5%, with the average being 1.3% and the median 1.0%. In general, rates have increased over the years, with 1.5% probably the average nowadays for new funds. 20% is the stated incentive rate that appears in about 80% of the ALPS-administered funds that have incentives.

Just a handful are higher, and those that are lower include some funds-of-funds, plus managers who are particularly sensitive to how their compensation impacts performance. The combination of a flat-rate fee and an incentive sounds pretty straightforward; however, there are a number of subtleties and parameter choices. Moreover, a manager contemplating a more complex structure has some additional decisions to consider. This discussion covers compensation issues and ALPS’ observations. Complexity Here’s one rule of thumb: the amount of time an investor spends trying to understand fees is inversely proportional to the likelihood of investing.

One example is a fund we reviewed in 2005. It had 3 fee schedules based on 3 liquidity schemes. The offering memorandum discussion ran to 5 pages as it detailed all the arithmetic needed if persons adopting one liquidity program had to change to another.

We’re professionals and it took hours to comprehend and to get all the variables onto a spreadsheet so as to figure out all the crossover points for all the variations. No thorough investor would tolerate such complexity. If the prospect has to spend more time understanding the fees than understanding the investment process, it’s not a favorable sales dynamic. Asset-Based Fees There are three principal structural choices related to asset-based fees: periodicity (when the fee is charged – generally monthly or quarterly); timing (in advance or arrears); and discounting.

In addition, there are semantics: most asset-based fees are termed “management fees;” however, some funds use a term like “expense reimbursement” or something similar. Since funds nearly universally calculate and disseminate monthly returns, asset-based fees need to be allocated monthly. If fees are defined in the legal documents as monthly – paid as well as calculated each month – it can simplify the administrator’s work, plus, those monthly fees will adjust each performance period. Versus a quarterly-in-advance fund, that will result in slightly higher fees in a successful fund, plus more closely align the monthly performance of existing investors and those who arrive mid-quarter. One other rule of thumb is that fee periodicity should never exceed withdrawal periodicity, e.g., quarterly fees and monthly liquidations don’t make sense. e-mail e l e m e n t s @ a l p s i n c .

c o m web w w w. a l p s i n c . c o m .

Compensation Variables continued ALPS is agnostic about in-advance or arrears; however, we pass along the following basic arithmetic: if an investor adds no money, a management fee payment in arrears as of January 31 on ending assets is equal to a payment February 1 on beginning assets. Therefore, the difference between advance and arrears is whether the manager gets one more fee payment at the beginning versus one more at the end. The payments in between will be the same. While the ending payment in arrears would hopefully be on a larger amount than the beginning payment in advance, the difference is likely not significant. What about quarterly fees? Again, keep in mind that it is nearly universal that funds report monthly performance, and no manager or investor wants fund performance skewed by the impact of full quarterly fees hitting the books only the first month of each quarter. Accordingly, ALPS spreads the effect of a quarterly fee over all three months. If fees are stated as being paid quarterly in advance, ALPS will amortize the fee amount on a straight-line basis over the quarter for reporting and relative participant percentage purposes. Likewise, when a management fee is defined as quarterly in arrears, it is accrued monthly, with each monthly amount equal to the fee amount through that point less the previously accrued amount. Note that the spreading of quarterly fees over the included months is an automated process; therefore, if unearned pre-paid fees are to be forfeited in a mid-quarter redemption, we ask that fund management be responsible for informing ALPS at the time of such redemption. ALPS Recommendation: if possible, match fee determinations to monthly fiscal periods: monthly in advance or arrears.

If a fund states quarterly fees, ensure that the accounting language is flexible enough to permit the spreading of the fee among the months in the quarter. Note that if there is a provision for the forfeiture of the unearned portion of a quarterly-in-advance fee in the event of an intra-quarter withdrawal, it should be stated in a way that does not affect the spreading of the fee among the months in the quarter. In our experience, most asset-based fee discounting is negotiated investor-by-investor when the institutional-size account asks for the accommodation. A size-based discount schedule is not usually set forth in the offering documents. Occasionally, funds will be structured to incorporate an “incremental” size-based discount such as 1.5% up to $1 million, plus 1% on amounts over that.

Alternatively, some may do this “stair-step” fashion: 1.5% up to $1 million or 1% if the account size is greater than that amount. This second method may be more effective in encouraging larger initial capital contributions since the amount of the discount is more substantial; however, there are some nuances. Do you really want to charge less to manage $1 million than $950K? Does it include profits? From the investor’s point of view, what if I give you the million and you lose 1% (dropping below the breakpoint); do my fees go up? Our recommendation on stair-steps is that profits be included in the consideration; after all, which account is more important – the $500K that has grown to $1.5 million over 5 years; or the new $1.5 million investor from last month? If profits are not included, there are also a number of mechanics and loopholes that would need to be addressed (Are withdrawn dollars contributions or profits? What happens when withdrawals are re-contributed?).

One solution is using a “ratchet” – meaning that once an investor attains the new stair-step rate, it is not affected by investment losses (withdrawals could cause a breakpoint rate change). An incremental sizebased discount does not have the breakpoint discontinuity, so these issues are moot. Note that some rare funds incorporate an incremental size-based fee scale that is applied to fund assets overall. This creates a slight incentive for existing investors to refer others. One last note about asset-based fees: what about forming a fund with no flat fee? We would advise against it.

Most sophisticated investors realize that it is in their best interests to invest in a fund where an asset-based fee is paying the rent. Having a manager who is solely dependent on an incentive may add to the risk of excessive speculation. Note: So that a fund might waive and/or reduce the asset-based fees as to any participant, they should be described and determined participant-by-participant based on capital account values, rather than at fund level, based on fund Net Asset Value. 2 © 1994 - Present ALPS e-mail e l e m e n t s @ a l p s i n c . c o m web w w w.

a l p s i n c . c o m . Compensation Variables continued Incentive Compensation The nuances multiply with incentives: In short, choices must be made regarding periodicity, high-water marks, hurdles (or thresholds) and hurdle benchmarks. Prior to a rule change in 1998, one-year measurement periods were required for all managers who were registered SEC investment advisers. Soon after that rule change, ALPS saw a rush to incorporate quarterly incentives; however, that appears to have tapered off. Clearly, investors would like the incentive to be calculated over as long a period as possible. In a quarterly incentive arrangement, it’s quite easy to visualize a situation where the investment manager gets a healthy incentive while an investor loses money over a year.

Especially with today’s volatility, a fund could be up 30% mid-year and give it all back by year-end, leaving the investor underwater solely because of a 6% incentive paid mid-year. Occurrences exactly like this in the last several years have caused some funds-of-funds to refuse investment with any manager not having an annual calculation. Note that, because of our perceptions of fairness to the investor, ALPS will not administer funds with monthly incentive periods. One other point is that investors should be permitted to withdraw as of the end of any incentive measurement period; an annual liquidity fund shouldn’t have quarterly incentives, for example. ALPS Recommendation: An annual measurement period is the best choice for marketability reasons. High-water marks are nearly universal, given the common perception that fairness would require a charge on profits to be only on real new profits.

We have seen variants of the high-water concept, such as a partial claw-back of previous period incentives in lieu of a high-water, but such arrangements have not been used widely. The argument for not having a high-water mark (or having it extinguish as time passes) is that talented employees of the manager may leave if a fund goes significantly underwater. The more distant the prospect of an incentive-funded payday at the fund, the tougher it becomes for the manager to retain staff. The offset, of course, is that investors below high-water often view the potential to recoup losses free of incentive as an asset.

In many cases, it becomes a reason to show more patience and stick with a fund that is down. Nowadays, in domestic funds, high-water marks are almost universally aggregate, meaning that an investor with multiple additions still has just one high-water mark. Back in the 1980’s, the lack of automation made this difficult, so contributions were often computed separately, with the result that an investor might pay an incentive on one contribution when, overall, he or she had experienced a loss. The downside for the manager was that investors would often balk at making added contributions during bad patches.

Conversely, an aggregate high-water mark can encourage capital additions – which also help the manager by reducing the percentage gains needed to get back to incentive territory. ALPS Recommendation: A durable, aggregate high-water mark is usually the best choice for marketability and investor retention. Note that in a “conventional” offshore fund, the series shares, not the investor, have the high water marks, so one series may pay an incentive while other series held by that investor are below high-water. As mentioned above, the “standard” incentive rate is 20% and one should keep in mind that both higher and lower rates can cause investor questions. On rates above 20%, due to the issues of realistic performance expectations over longer periods of time, ALPS recommends their use only if coupled with a hurdle. What about a schedule where the manager receives 20% of profits up to one level of return and a higher rate above that? ALPS does not support such arrangements for both philosophical and practical reasons. Philosophically, receiving 20% of all profits means that the manager is already being compensated for the higher return, plus there is the insertion of added manager-investor conflicts of 3 © 1994 - Present ALPS e-mail e l e m e n t s @ a l p s i n c .

c o m web w w w. a l p s i n c . c o m .

Compensation Variables continued interest when returns are near the breakpoint. On the practical side, such schedules are very difficult to automate (and to articulate clearly within the offering documents) when one considers the prospect of intra-year additions and withdrawals, plus partial year periods for some newer investors. Hurdles and Thresholds Hurdles, which would seem attractive from a marketing perspective, are not as common as one might expect. We would guess perhaps 10% of funds contain one of the two structures that are commonly called hurdles. In our parlance, a true “hurdle” means that the return in excess of a defined benchmark is charged an incentive allocation.

A “threshold,” on the other hand, means that the incentive allocation is calculated on the entire gain, provided that it cannot reduce the return below the benchmark return. Most benchmarks are a simple rate of return such as 5% or 10%, although some use T-bills or equity indexes. A hedge fund should choose a hurdle benchmark carefully, keeping in mind that a fund with a short component is not really part of the “equity” asset class. That is one reason that an equity benchmark such as the S&P 500 is not often used for hurdles in “hedged” hedge funds. Measurements of hurdles and thresholds are generally not cumulative. In addition to the complexity, both investors and managers have an interest in an underperforming fund not getting “too far behind.” As noted above, there may be issues related to employee retention and fund viability, plus there is the realism that a hurdle is an investor accommodation that most funds don’t offer.

Thus, the norm in the industry is that those funds that provide hurdles measure them on a year-by year basis. Another question on a hurdle or threshold is “5% of what?” Beginning capital or the high-water mark? If the math is based on a capital account which is “under water,” the high-water mark recoupment may make the hurdle less meaningful or perhaps irrelevant. General Notes: Legal descriptions for hurdle calculations are often more cumbersome if they contain extensive references to percentage returns. ALPS recommends a reference to a hurdle return – a dollar calculation arrived at by applying a hurdle rate times either capital or the high-water mark. This calculation must be tracked on a monthly basis in order to accommodate additions and withdrawals. Hurdles must properly compound in order to properly reflect additions and withdrawals: a 12% hurdle is 0.95% per month – not 1.00%, so references should be carefully examined. It is often best to simply refer to the annual rate. For fairness and precision, we suggest that all incentive allocations be described and determined participant-by-participant based on capital account gains after all other fees and expenses. Note that using a hurdle benchmark that can decline adds some wrinkles.

For example, what happens when the index declines 30% and the fund declines only 20%? It is commonly agreed that charging an incentive for achieving a “lesser loss” is not a marketable strategy. However, over the long run, a cumulative hurdle that ignores lesser losses will significantly reduce the incentive earned by the fund manager. The most common industry solution is the following set of rules: 1) Hurdles are not cumulative – the hurdle base is reset to high-water capital each year.

This achieves two purposes; one, it offsets the “lesser losses” issue; secondly, it prevents a fund from “digging too deep a hole” from under performing the index. It is conceivable that a “hedged” fund could get behind a quickly rising index and remain there for some time, all the while achieving an objective of lowered risk and reasonable returns. 2) The incentive is calculated on the difference between fund results and benchmark return; however, it is limited to the amount of real profit. For example, if the fund were up 2% and the benchmark down -23%, 20% of the differential return (+25%) would be 5%; however, the manager allocation would be limited to only 2%, since it can’t exceed the actual profit amount.

This eliminates 4 © 1994 - Present ALPS e-mail e l e m e n t s @ a l p s i n c . c o m web w w w. a l p s i n c .

c o m . Compensation Variables continued the “lesser losses” issue but can mean that the manager may be allocated more than 20% of the actual profit (in this case, 100%). Note, however, that while the manager is allocated 100% of the profits, the fund results have beat the benchmark by 25%, so the incentive rate works out to be only 8% of the 25 point differential. As noted above, for most hedge funds that have a hedge component, a pure equity benchmark is probably not appropriate. An index like the S&P 500 may have had an average annual return of 12% over the last 20 years, but only 4 years were within 5 percentage points of 12%. 60% of the time, the S&P 500 annual return has been more than 20% or less than zero; it is a highly volatile index. Accordingly, if reduction of volatility is an objective of the fund, it would not seem logical to tie compensation to a highly volatile index. As mentioned above, most hurdles, index-related or fixed, reset each year.

Either beginning capital or the beginning high-water mark would be the starting point for the hurdle return calculation. General The characteristics and structure of manager compensation will likely have tax implications for both investors and management. For example, you will note that, in domestic funds, the word “fee” will not normally be associated with incentive compensation (in offshore funds organized as corporations, it’s a different story). In addition, in some jurisdictions, legal counsel may recommend a division of payment – the asset-based fee going to one entity and the incentive allocation to another. Accordingly, it is important to seek competent legal counsel in the drafting stage and to vet documents with the fund’s auditor. Often, a manager may encourage investments by offering a lower management fee or incentive rate for an initial period.

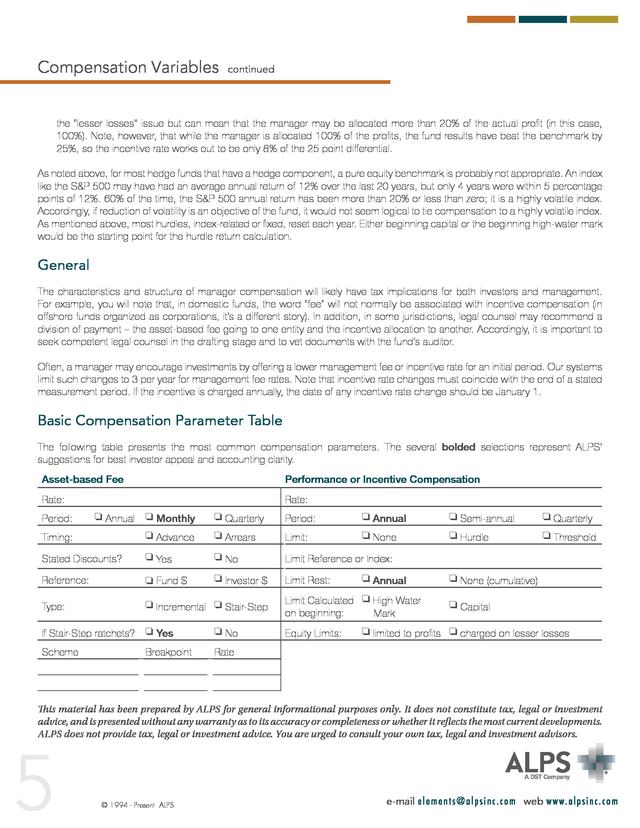

Our systems limit such changes to 3 per year for management fee rates. Note that incentive rate changes must coincide with the end of a stated measurement period. If the incentive is charged annually, the date of any incentive rate change should be January 1. Basic Compensation Parameter Table The following table presents the most common compensation parameters.

The several bolded selections represent ALPS’ suggestions for best investor appeal and accounting clarity. Asset-based Fee Performance or Incentive Compensation Rate: Rate: o Monthly o Quarterly Period: o Annual o Semi-annual o Quarterly Timing: o Advance o Arrears Limit: o None o Hurdle o Threshold Stated Discounts? o Yes o No Limit Reference or Index: Reference: o Fund $ o Investor $ Limit Rest: Type: o Incremental o Stair-Step Period: o Annual If Stair-Step ratchets? o Yes o No Scheme o Annual o None (cumulative) Limit Calculated o High Water o Capital on beginning: Mark Rate Breakpoint Equity Limits: o limited to profits o charged on lesser losses This material has been prepared by ALPS for general informational purposes only. It does not constitute tax, legal or investment advice, and is presented without any warranty as to its accuracy or completeness or whether it reflects the most current developments. ALPS does not provide tax, legal or investment advice. You are urged to consult your own tax, legal and investment advisors. 5 © 1994 - Present ALPS e-mail e l e m e n t s @ a l p s i n c .

c o m web w w w. a l p s i n c . c o m .

This discussion is intended to set forth our observations on the current state of the art. First of all, how many people can name a dozen managers who returned 17% gross over the last twenty years? In a “two and twenty” hedge fund (manager compensation of 2% of assets plus 20% of profits), 17% turns into 12% net – just about what the S&P 500 has returned in the 20 years since October 1987. That is not to say that hedge fund fees are not fair – just that investors often expect something else in addition to the returns; such as consistency, superior risk control or diminished or negative correlation with their other investments. The point is that compensation choices should be decided within the context of the fund’s expected style and investment profile. Currently, we see annual management fees ranging from about 0.5% to 2.5%, with the average being 1.3% and the median 1.0%. In general, rates have increased over the years, with 1.5% probably the average nowadays for new funds. 20% is the stated incentive rate that appears in about 80% of the ALPS-administered funds that have incentives.

Just a handful are higher, and those that are lower include some funds-of-funds, plus managers who are particularly sensitive to how their compensation impacts performance. The combination of a flat-rate fee and an incentive sounds pretty straightforward; however, there are a number of subtleties and parameter choices. Moreover, a manager contemplating a more complex structure has some additional decisions to consider. This discussion covers compensation issues and ALPS’ observations. Complexity Here’s one rule of thumb: the amount of time an investor spends trying to understand fees is inversely proportional to the likelihood of investing.

One example is a fund we reviewed in 2005. It had 3 fee schedules based on 3 liquidity schemes. The offering memorandum discussion ran to 5 pages as it detailed all the arithmetic needed if persons adopting one liquidity program had to change to another.

We’re professionals and it took hours to comprehend and to get all the variables onto a spreadsheet so as to figure out all the crossover points for all the variations. No thorough investor would tolerate such complexity. If the prospect has to spend more time understanding the fees than understanding the investment process, it’s not a favorable sales dynamic. Asset-Based Fees There are three principal structural choices related to asset-based fees: periodicity (when the fee is charged – generally monthly or quarterly); timing (in advance or arrears); and discounting.

In addition, there are semantics: most asset-based fees are termed “management fees;” however, some funds use a term like “expense reimbursement” or something similar. Since funds nearly universally calculate and disseminate monthly returns, asset-based fees need to be allocated monthly. If fees are defined in the legal documents as monthly – paid as well as calculated each month – it can simplify the administrator’s work, plus, those monthly fees will adjust each performance period. Versus a quarterly-in-advance fund, that will result in slightly higher fees in a successful fund, plus more closely align the monthly performance of existing investors and those who arrive mid-quarter. One other rule of thumb is that fee periodicity should never exceed withdrawal periodicity, e.g., quarterly fees and monthly liquidations don’t make sense. e-mail e l e m e n t s @ a l p s i n c .

c o m web w w w. a l p s i n c . c o m .

Compensation Variables continued ALPS is agnostic about in-advance or arrears; however, we pass along the following basic arithmetic: if an investor adds no money, a management fee payment in arrears as of January 31 on ending assets is equal to a payment February 1 on beginning assets. Therefore, the difference between advance and arrears is whether the manager gets one more fee payment at the beginning versus one more at the end. The payments in between will be the same. While the ending payment in arrears would hopefully be on a larger amount than the beginning payment in advance, the difference is likely not significant. What about quarterly fees? Again, keep in mind that it is nearly universal that funds report monthly performance, and no manager or investor wants fund performance skewed by the impact of full quarterly fees hitting the books only the first month of each quarter. Accordingly, ALPS spreads the effect of a quarterly fee over all three months. If fees are stated as being paid quarterly in advance, ALPS will amortize the fee amount on a straight-line basis over the quarter for reporting and relative participant percentage purposes. Likewise, when a management fee is defined as quarterly in arrears, it is accrued monthly, with each monthly amount equal to the fee amount through that point less the previously accrued amount. Note that the spreading of quarterly fees over the included months is an automated process; therefore, if unearned pre-paid fees are to be forfeited in a mid-quarter redemption, we ask that fund management be responsible for informing ALPS at the time of such redemption. ALPS Recommendation: if possible, match fee determinations to monthly fiscal periods: monthly in advance or arrears.

If a fund states quarterly fees, ensure that the accounting language is flexible enough to permit the spreading of the fee among the months in the quarter. Note that if there is a provision for the forfeiture of the unearned portion of a quarterly-in-advance fee in the event of an intra-quarter withdrawal, it should be stated in a way that does not affect the spreading of the fee among the months in the quarter. In our experience, most asset-based fee discounting is negotiated investor-by-investor when the institutional-size account asks for the accommodation. A size-based discount schedule is not usually set forth in the offering documents. Occasionally, funds will be structured to incorporate an “incremental” size-based discount such as 1.5% up to $1 million, plus 1% on amounts over that.

Alternatively, some may do this “stair-step” fashion: 1.5% up to $1 million or 1% if the account size is greater than that amount. This second method may be more effective in encouraging larger initial capital contributions since the amount of the discount is more substantial; however, there are some nuances. Do you really want to charge less to manage $1 million than $950K? Does it include profits? From the investor’s point of view, what if I give you the million and you lose 1% (dropping below the breakpoint); do my fees go up? Our recommendation on stair-steps is that profits be included in the consideration; after all, which account is more important – the $500K that has grown to $1.5 million over 5 years; or the new $1.5 million investor from last month? If profits are not included, there are also a number of mechanics and loopholes that would need to be addressed (Are withdrawn dollars contributions or profits? What happens when withdrawals are re-contributed?).

One solution is using a “ratchet” – meaning that once an investor attains the new stair-step rate, it is not affected by investment losses (withdrawals could cause a breakpoint rate change). An incremental sizebased discount does not have the breakpoint discontinuity, so these issues are moot. Note that some rare funds incorporate an incremental size-based fee scale that is applied to fund assets overall. This creates a slight incentive for existing investors to refer others. One last note about asset-based fees: what about forming a fund with no flat fee? We would advise against it.

Most sophisticated investors realize that it is in their best interests to invest in a fund where an asset-based fee is paying the rent. Having a manager who is solely dependent on an incentive may add to the risk of excessive speculation. Note: So that a fund might waive and/or reduce the asset-based fees as to any participant, they should be described and determined participant-by-participant based on capital account values, rather than at fund level, based on fund Net Asset Value. 2 © 1994 - Present ALPS e-mail e l e m e n t s @ a l p s i n c . c o m web w w w.

a l p s i n c . c o m . Compensation Variables continued Incentive Compensation The nuances multiply with incentives: In short, choices must be made regarding periodicity, high-water marks, hurdles (or thresholds) and hurdle benchmarks. Prior to a rule change in 1998, one-year measurement periods were required for all managers who were registered SEC investment advisers. Soon after that rule change, ALPS saw a rush to incorporate quarterly incentives; however, that appears to have tapered off. Clearly, investors would like the incentive to be calculated over as long a period as possible. In a quarterly incentive arrangement, it’s quite easy to visualize a situation where the investment manager gets a healthy incentive while an investor loses money over a year.

Especially with today’s volatility, a fund could be up 30% mid-year and give it all back by year-end, leaving the investor underwater solely because of a 6% incentive paid mid-year. Occurrences exactly like this in the last several years have caused some funds-of-funds to refuse investment with any manager not having an annual calculation. Note that, because of our perceptions of fairness to the investor, ALPS will not administer funds with monthly incentive periods. One other point is that investors should be permitted to withdraw as of the end of any incentive measurement period; an annual liquidity fund shouldn’t have quarterly incentives, for example. ALPS Recommendation: An annual measurement period is the best choice for marketability reasons. High-water marks are nearly universal, given the common perception that fairness would require a charge on profits to be only on real new profits.

We have seen variants of the high-water concept, such as a partial claw-back of previous period incentives in lieu of a high-water, but such arrangements have not been used widely. The argument for not having a high-water mark (or having it extinguish as time passes) is that talented employees of the manager may leave if a fund goes significantly underwater. The more distant the prospect of an incentive-funded payday at the fund, the tougher it becomes for the manager to retain staff. The offset, of course, is that investors below high-water often view the potential to recoup losses free of incentive as an asset.

In many cases, it becomes a reason to show more patience and stick with a fund that is down. Nowadays, in domestic funds, high-water marks are almost universally aggregate, meaning that an investor with multiple additions still has just one high-water mark. Back in the 1980’s, the lack of automation made this difficult, so contributions were often computed separately, with the result that an investor might pay an incentive on one contribution when, overall, he or she had experienced a loss. The downside for the manager was that investors would often balk at making added contributions during bad patches.

Conversely, an aggregate high-water mark can encourage capital additions – which also help the manager by reducing the percentage gains needed to get back to incentive territory. ALPS Recommendation: A durable, aggregate high-water mark is usually the best choice for marketability and investor retention. Note that in a “conventional” offshore fund, the series shares, not the investor, have the high water marks, so one series may pay an incentive while other series held by that investor are below high-water. As mentioned above, the “standard” incentive rate is 20% and one should keep in mind that both higher and lower rates can cause investor questions. On rates above 20%, due to the issues of realistic performance expectations over longer periods of time, ALPS recommends their use only if coupled with a hurdle. What about a schedule where the manager receives 20% of profits up to one level of return and a higher rate above that? ALPS does not support such arrangements for both philosophical and practical reasons. Philosophically, receiving 20% of all profits means that the manager is already being compensated for the higher return, plus there is the insertion of added manager-investor conflicts of 3 © 1994 - Present ALPS e-mail e l e m e n t s @ a l p s i n c .

c o m web w w w. a l p s i n c . c o m .

Compensation Variables continued interest when returns are near the breakpoint. On the practical side, such schedules are very difficult to automate (and to articulate clearly within the offering documents) when one considers the prospect of intra-year additions and withdrawals, plus partial year periods for some newer investors. Hurdles and Thresholds Hurdles, which would seem attractive from a marketing perspective, are not as common as one might expect. We would guess perhaps 10% of funds contain one of the two structures that are commonly called hurdles. In our parlance, a true “hurdle” means that the return in excess of a defined benchmark is charged an incentive allocation.

A “threshold,” on the other hand, means that the incentive allocation is calculated on the entire gain, provided that it cannot reduce the return below the benchmark return. Most benchmarks are a simple rate of return such as 5% or 10%, although some use T-bills or equity indexes. A hedge fund should choose a hurdle benchmark carefully, keeping in mind that a fund with a short component is not really part of the “equity” asset class. That is one reason that an equity benchmark such as the S&P 500 is not often used for hurdles in “hedged” hedge funds. Measurements of hurdles and thresholds are generally not cumulative. In addition to the complexity, both investors and managers have an interest in an underperforming fund not getting “too far behind.” As noted above, there may be issues related to employee retention and fund viability, plus there is the realism that a hurdle is an investor accommodation that most funds don’t offer.

Thus, the norm in the industry is that those funds that provide hurdles measure them on a year-by year basis. Another question on a hurdle or threshold is “5% of what?” Beginning capital or the high-water mark? If the math is based on a capital account which is “under water,” the high-water mark recoupment may make the hurdle less meaningful or perhaps irrelevant. General Notes: Legal descriptions for hurdle calculations are often more cumbersome if they contain extensive references to percentage returns. ALPS recommends a reference to a hurdle return – a dollar calculation arrived at by applying a hurdle rate times either capital or the high-water mark. This calculation must be tracked on a monthly basis in order to accommodate additions and withdrawals. Hurdles must properly compound in order to properly reflect additions and withdrawals: a 12% hurdle is 0.95% per month – not 1.00%, so references should be carefully examined. It is often best to simply refer to the annual rate. For fairness and precision, we suggest that all incentive allocations be described and determined participant-by-participant based on capital account gains after all other fees and expenses. Note that using a hurdle benchmark that can decline adds some wrinkles.

For example, what happens when the index declines 30% and the fund declines only 20%? It is commonly agreed that charging an incentive for achieving a “lesser loss” is not a marketable strategy. However, over the long run, a cumulative hurdle that ignores lesser losses will significantly reduce the incentive earned by the fund manager. The most common industry solution is the following set of rules: 1) Hurdles are not cumulative – the hurdle base is reset to high-water capital each year.

This achieves two purposes; one, it offsets the “lesser losses” issue; secondly, it prevents a fund from “digging too deep a hole” from under performing the index. It is conceivable that a “hedged” fund could get behind a quickly rising index and remain there for some time, all the while achieving an objective of lowered risk and reasonable returns. 2) The incentive is calculated on the difference between fund results and benchmark return; however, it is limited to the amount of real profit. For example, if the fund were up 2% and the benchmark down -23%, 20% of the differential return (+25%) would be 5%; however, the manager allocation would be limited to only 2%, since it can’t exceed the actual profit amount.

This eliminates 4 © 1994 - Present ALPS e-mail e l e m e n t s @ a l p s i n c . c o m web w w w. a l p s i n c .

c o m . Compensation Variables continued the “lesser losses” issue but can mean that the manager may be allocated more than 20% of the actual profit (in this case, 100%). Note, however, that while the manager is allocated 100% of the profits, the fund results have beat the benchmark by 25%, so the incentive rate works out to be only 8% of the 25 point differential. As noted above, for most hedge funds that have a hedge component, a pure equity benchmark is probably not appropriate. An index like the S&P 500 may have had an average annual return of 12% over the last 20 years, but only 4 years were within 5 percentage points of 12%. 60% of the time, the S&P 500 annual return has been more than 20% or less than zero; it is a highly volatile index. Accordingly, if reduction of volatility is an objective of the fund, it would not seem logical to tie compensation to a highly volatile index. As mentioned above, most hurdles, index-related or fixed, reset each year.

Either beginning capital or the beginning high-water mark would be the starting point for the hurdle return calculation. General The characteristics and structure of manager compensation will likely have tax implications for both investors and management. For example, you will note that, in domestic funds, the word “fee” will not normally be associated with incentive compensation (in offshore funds organized as corporations, it’s a different story). In addition, in some jurisdictions, legal counsel may recommend a division of payment – the asset-based fee going to one entity and the incentive allocation to another. Accordingly, it is important to seek competent legal counsel in the drafting stage and to vet documents with the fund’s auditor. Often, a manager may encourage investments by offering a lower management fee or incentive rate for an initial period.

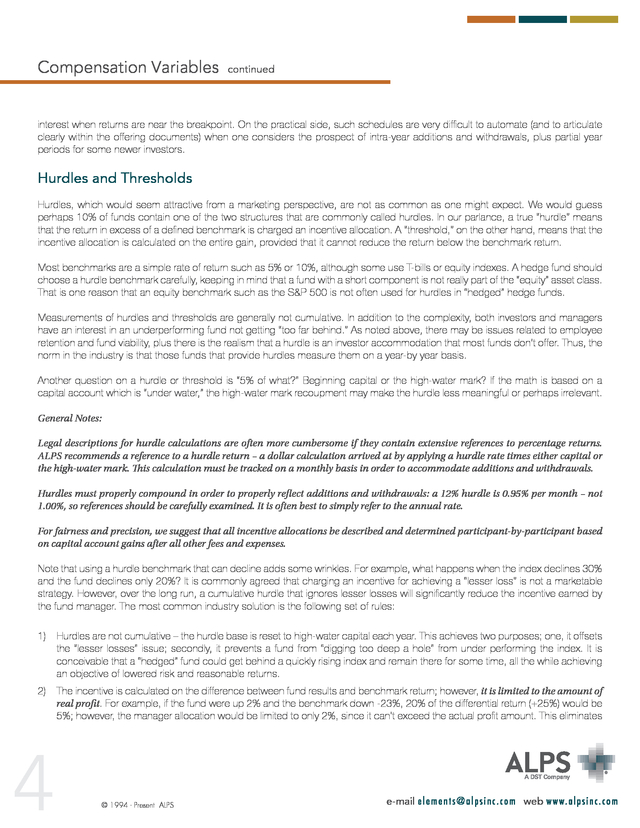

Our systems limit such changes to 3 per year for management fee rates. Note that incentive rate changes must coincide with the end of a stated measurement period. If the incentive is charged annually, the date of any incentive rate change should be January 1. Basic Compensation Parameter Table The following table presents the most common compensation parameters.

The several bolded selections represent ALPS’ suggestions for best investor appeal and accounting clarity. Asset-based Fee Performance or Incentive Compensation Rate: Rate: o Monthly o Quarterly Period: o Annual o Semi-annual o Quarterly Timing: o Advance o Arrears Limit: o None o Hurdle o Threshold Stated Discounts? o Yes o No Limit Reference or Index: Reference: o Fund $ o Investor $ Limit Rest: Type: o Incremental o Stair-Step Period: o Annual If Stair-Step ratchets? o Yes o No Scheme o Annual o None (cumulative) Limit Calculated o High Water o Capital on beginning: Mark Rate Breakpoint Equity Limits: o limited to profits o charged on lesser losses This material has been prepared by ALPS for general informational purposes only. It does not constitute tax, legal or investment advice, and is presented without any warranty as to its accuracy or completeness or whether it reflects the most current developments. ALPS does not provide tax, legal or investment advice. You are urged to consult your own tax, legal and investment advisors. 5 © 1994 - Present ALPS e-mail e l e m e n t s @ a l p s i n c .

c o m web w w w. a l p s i n c . c o m .