RSM Reporting - The technical developments in global accounting and reporting - Issue 26 - January 29, 2016

RSM US (formerly McGladrey)

Description

january 2016 - Issue 26

RSM reporting

Technical developments in global accounting and reporting.

THE POWER OF BEING UNDERSTOOD

AUDIT | TAX | CONSULTING

. Welcome

Happy New Year!

As we enter into the second decade of IFRS in Europe, in this

issue we reflect on the lessons learnt from the past and on

what we should look forward to in the next decade. Our guest

contributor, Dr Nigel Sleigh-Johnson, Head of the Financial

Reporting Faculty at ICAEW, shared with us his insightful

views, providing a start to the New Year under the best

auspices of a promising new decade of IFRS.

If the recent capital market trends are anything to go by,

investment funds, private equity and venture capital will

continue to play a prominent role in our economies. Therefore,

our author from Singapore, Chee Wee Lock, addresses the

challenges and the advantages of the additional information

required in the context of consolidation (and exemption from

consolidation) of investment entities’ subsidiaries.

Joelle Moughanni builds on the previous issue’s guest

contributor and focuses on the much discussed disclosure

debate (and IASB’s initiative) in a selection of the ten most

relevant questions and answers.

The issue closes with the latest on topics RSM has focused

on, the selected technical advice of the quarter, and RSM’s

contribution to the IASB’s public consultation on a number

of topics.

We hope you will find this issue insightful and helpful.

Enjoy your reading!

Dr Marco Mongiello ACA

m.mongiello@surrey.ac.uk

. “ in this issue we reflect on the

lessons learnt from the past

and on what we should look

forward to in the next decade.”

. Nigel is Head of ICAEW’s Financial Reporting Faculty. He has

responsibility for overseeing the development of ICAEW policy on

financial and non-financial reporting issues and is a regular media

commentator and speaker on financial reporting issues. Nigel

was a major contributor to ICAEW’s 2007 study for the EU, ‘EU

Implementation of IFRS’ and co-author of ICAEW’s publications

‘The Future of IFRS’ (2012) and ‘Moving to IFRS reporting; Seven

lessons learned from the European experience’ (2015).He is a

member of FEE’s Corporate Reporting Policy Group and since

2014 has been a member of the Department for Business

Innovation & Skills’ expert working group on UK company law,

the Accounting Directive Stakeholder Group. Nigel is an ICAEW

Chartered Accountant and has a PhD from London University.

A Conversation with Nigel SleighJohnson, Head of the Financial

Reporting Faculty at ICAEW

by Marco Mongiello, Editor

As last year marked the first decade of international

accounting and reporting widely applied in Europe and a

continuously growing number of other countries, it seems

natural that we start the New Year reflecting on what the

next decade of international accounting may look like and

how we can influence it.

To this end, I am grateful to Dr Nigel Sleigh-Johnson, Head of the Financial Reporting Faculty at ICAEW and co-author of ‘Moving to IFRS reporting: seven lessons learned from the European experience’, for sharing his personal views with us. With one eye on his publication and the other on my first question, which is about his insights into the next decade, Nigel starts in a very positive way: NSJ: The progress we have experienced in the past ten years is remarkable. While we are not going to see an easy journey towards universal accounting standards, there are very good signs of incremental change. I have just been in Japan and the interest in moving towards the adoption of IFRS is tremendous. I recently met the chairman of the Indonesian accounting standard setters, who too showed a commitment towards the adoption of IFRS. They do have different paths towards adoption.

They have different challenges and the timetables are not always clear. However, I think that those who are looking at the lessons learnt from the European experience find very positive messages. And, of course, the lessons do not come just from Europe, there are other countries too, for example, Australia, South Korea and South Africa. The story is different in each case, but what they all have in common is that they are moving in the right direction.

For example, in India they have a conversion process, where the deadlines moved several times. Nevertheless, the Indian commitment in moving in the direction of IFRS reporting is there. Similarly, we see the same commitment in China, where they are very close to a full convergence plan.

There are still differences, but there is no doubt that Chinese accounting standards are close to IFRS. In terms of the US, that remains a real challenge. It is very significant and encouraging that the SEC has permitted foreign companies to file accounts using IFRS without reconciliation. As the SEC is one of the largest IFRS regulators in the world and the US is one of the largest economies and capital markets in the world, the convergence achieved is very significant.

The US interest in moving towards IFRS remains a long term ambition though, because the US has a very strong tradition of accounting and a distinctive regulatory and legal environment. I feel encouraged by the comments that the SEC Chief Accountant, James Schnurr, made in December 2014, when he was relatively new in the job. He talked about allowing US domestic registered companies to publish information using IFRS, alongside US GAAP filings, without reconciliation. He touched on that again in other public talks in May and in September 2015. So, although we are not going to see a switch to IFRS in the US any time soon, nevertheless this idea of non-reconciliation is potentially a major concession. One current concern with converged standards like IFRS 15, is the likelihood that we will see the SEC and other US bodies issue reams of amendments and guidance to solve interpretation challenges. On this note, a slight worry is that other jurisdictions, like Japan, which have a rules-based approach similar to the US, are looking with some interest at these forthcoming amendments and guidance, creating the possibility of a new layer of IFRS interpretative material in those jurisdictions. MM: Will this lead to major adaptations in the adoption processes of jurisdictions that are new to IFRS? Is there a danger that large economies like China or India may look at the European endorsement process and, imitating its principle, end up making significant changes to the IFRS when adopting them? .

NSJ: One of the lessons that emerged from the study of the past decade of IFRS implementation in Europe is that the endorsement and adoption process has so far almost invariably resulted in full endorsement. It is, however, very tempting for governments to make significant changes. This is why we need to promote an understanding of the drawbacks of doing this. When I was in Japan recently, I spoke with Japanese regulators in these terms.

We are currently doing so in other countries like Indonesia, and we are not the only ones disseminating this message. In fact, the debate about IFRS started in the early 70’s; it has taken decades to reach the point where we are now and the debate is still ongoing. Taking a historical perspective, 100 years is not a long period of time, let alone a decade. So, as much as I would like to live long enough to see IFRS adopted universally, I am not sure this will happen! In the meantime, there will be an emergence of different dialects of the international language of accounting, which will bring a basis for common understanding. There is not any easy global analogy to be drawn here; having a set of standards issued by a single private organisation and being adopted globally has never happened and we cannot predict the outcome.

It is nevertheless extraordinary what has been achieved so far; jurisdictions around the world adopting IFRS is a huge step forward, which can only improve global prosperity and stability. Financial reporting is, after all, an economic fundamental. There has also been great progress in the direction of exchanging information and networking among standard setters around the world. There is a lot more to be done, though, in terms of coordination with countries that are now approaching IFRS. If you look back at 2005, there has been a tremendous transformation and I like to think that one instigator of this change is ICAEW, which has played an important role in the development of IFRS since their initial conception in the 70’s, providing independent and unbiased contributions to the IFRS debate.

The key for us [ICAEW] in all of this has always been to promote the public interest. MM: Speaking about public interest, there are interesting developments in international reporting, which are very effectively championed by the International Integrated Reporting Council1 and their proposed approach to reporting that integrates financial, social, environmental and other aspects of companies’ impact and performance in one place. Is this contradicting the efforts towards reducing the length of the annual reports? NSJ: It is a complex situation. Business transactions have become much more complex over time. You have to ensure that the information is available for investors using it to form their judgements, but you can certainly go too far in trying to tackle complexity.

Nonetheless, it is very important for the IASB to acknowledge the need to make the standards as clear as possible, still always keeping in mind the overarching principle of cost/benefit in reporting. A good example is the enormous complexity of the old draft standard for leasing; the message has certainly been heard and the new standard on leasing in its final form has gone through a massive simplification. On the other hand, you are never going to eliminate complexity from financial reporting.

Discussions have taken place, particularly through the Lab2, where investors and preparers provide very different answers to the challenges and needs of reporting, but everyone agrees on writing and signposting more clearly. There are remarkable examples of listed companies large and small that report in an easy-to-follow way, even though their businesses may be complex. Especially if you look at the front end of the accounts, the ideas of better reporting of strategy and KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) have been around for a long time, but now they are coming to fruition in a more joined-up way, providing a very clear picture of where the company is, where it is heading and what its challenges are. I was very impressed by some of the smaller quoted companies’ reports I have reviewed recently. To your question, if you have improvements at the front end, consistency throughout, the IASB keeping complexity to a 1 Editor’s note: we reported about IIRC in the newsletter in issue 23 Editor’s note: the Lab is an initiative of the FRC, whose inception was reported in the newsletter in issue 12, which brings together users and preparers of companies’ accounts to debate and propose mutually beneficial developments in reporting. 2 .

minimum and an acceptance that accounts are not going to become much shorter – these are ways of improving annual reports. The IIRC has an even wider view of integration in corporate reports; and there are, of course, demands for major companies to be more accountable in many ways (environmental impact, taxation, social impacts and so on). It is a good thing that there are movements to encourage greater transparency and accountability. However, we do have a view at ICAEW that it is important not to clutter the traditional annual reports and accounts with regulatory requirements that are not primarily directed to the information needs of investors.

So, one can see improvements taking place within UK annual reports, but we are going to see integrated annual reporting developing in different ways around the world, depending on existing frameworks and cultures in different jurisdictions; in some jurisdictions mandating integrated reporting may be the most effective way of encouraging people to apply it, in others, like the UK, where the annual report is well developed and generally informative, mandating would not be helpful. MM: So, what are your predictions for the next ten years? NSJ: Taking the perspective of the next ten years, I think that the future of IFRS presents challenges that are as great as those of the past ten years. In a sense, phase one has been completed successfully, but it is one of many phases on a journey towards global reporting. There is a huge amount to aim for and there are very good signs that we will make substantial progress over the next ten years, but this must be coupled with recognition that things are unpredictable in many ways.

For example, we cannot be sure of the direction in which the US will move. The world is a tremendously diverse place and although there are trends towards globalisation, there are strong traditions and cultures which we are not going to overturn in our lifetime. Hence, although I believe that there will always be a degree of diversity in interpretations, what we have achieved in the first ten years is a huge step forward and puts us on a good path for the next ten years. MM: We talk about the challenges of globalisation because of differences in jurisdictions’ cultures and regulations, but another aspect of the challenge is the differences in sectors and industries – in particular, new high-tech and highly innovative companies.

With regard to some of these companies, investors are no longer interested in looking at traditional measures like the operating profit or gross profit. Take the examples of Tesla Motors, LinkedIn and Facebook, where investors are not looking at the same ratios as they would for more traditional companies in established industries. Should IFRS suggest sets of KPIs that may be more useful for different companies? . NSJ: I think that this is an important area that calls for different stakeholders to come together and discuss a solution. Having some sort of forum to achieve that would be tremendously beneficial. I am not sure that including KPIs in IASB’s Standards is the right answer, though. However, a wider group of stakeholders could potentially agree on relevant KPIs for particular sectors.

Initiatives in this area would be very sensible; this could indeed be a theme of the next ten years. In this debate, we, at ICAEW, tend to think that the IASB should not be writing different standards for different sectors. It should be possible to establish principles and concepts that can apply to all reporting entities. This is achieved by principles being tested across widely different sectors during the development of a standard to ensure they can be applied consistently and without practical difficulties across sectors. On the other hand, major companies tend, in practice, to keep a close eye on each other’s annual reports, which should create and promote not just a degree of consistency but even some convergence of industry norms. In some circumstances at least, companies in the same sectors talk to each other to exchange views on reporting; this is terribly healthy and there is a case for doing more in this direction.

Perhaps exploring accounting norms for specific sectors is something to be debated during the next phase. I’d just add, though, that the companies you mention are still start-ups or fairly young, so they either haven’t made a profit yet or their current profits are not what investors hope to see from them in the future. I don’t think in those circumstances it’s just about sectorial issues. MM: To those (if there still is anyone) who say that accounting and reporting is all about the past, Nigel SleighJohnson’s words will be eye opening. For the majority of us, I am sure, they come as an inspiring call to renew our energy and passion for global accounting and reporting because the past ten years are nothing but the very beginning of an exciting, long journey. .

Are investment funds shortchanged by the exemption from consolidation with more efforts and disclosures required by fair value accounting? By Chee Wee Lock, Partner and Industry Leader of Professional & Business Services Vertical Industry Group, RSM Singapore ƒƒ commits to its investors that its business purpose is to invest funds solely for returns from capital appreciation, investment income or both; and Amendments to IFRS 10, Consolidated Financial Statements, IFRS 12, Disclosure of Interests in Other Entities and IAS 27, Separate Financial Statements on Investment Entities (IE) provide an exemption from consolidation for investment funds and similar entities. As such, an IE records its investments in subsidiaries at fair value through profit or loss, instead of consolidating them. The main reason for such preferential treatment is that the IE operates in a unique business model where fair value information is provided to its users and such fair value information is more useful for the stakeholders within the IE’s ecosystem. However, the assessment whether an entity qualified as an IE is not straightforward.

Let us explore closely. ƒƒ measures and evaluates the performance of substantially all of its investments on a fair value basis.” First, the assessment needs to consider all facts and circumstances such as the purpose and design of the entity. Before we can do such consideration, let us understand the definition of an IE. An IE is3 4 “an entity that: ƒƒ obtains funds from one or more investors for the purpose of providing those investors with investment management services; If it is apparent from its corporate documents or offering memorandum that the purpose of the entity is to solicit funds from its investor or investors and to invest them solely to gain from capital appreciation or investment income, then the entity can be an IE. Conversely, if an entity states to its investors that it is making an investment to develop, manufacture or promote products with its investees, it appears its business purpose is inconsistent with that of an IE. After the IE meets all the essential elements of the definition of IE, it then needs to have one or more of the following typical characteristics5: ƒƒ holds more than one investment; ƒƒ has more than one investor; ƒƒ has investors that are not the IE’s related parties; and ƒƒ has ownership interests in the form of equity or similar interests. .

Even when it does not have all the typical characteristics, management may still judge that the entity is nonetheless an IE, although a disclosure of such management judgement is required. A further requirement is that an IE’s6 subsidiary that provides investment-related services (such as advisory, investment management and administrative support) will be required to be consolidated by the IE7. It may seem that the IE would benefit from cost and time savings when it is provided an exemption from consolidation. Also, it would appear that users of financial statements can now better assess the financial position, performance and cash flows of the IE, instead of using consolidated financial statements that also comprise of the investees’ figures. As such, more meaningful and useful information could now be obtained by investors of the IE since fair value is what they are interested in, together with income and capital appreciation.

These investors are not interested in (and no longer bother with) the line-by-line consolidation of the investees’ assets and liabilities as they have no title to these assets, have no obligation to these liabilities and are not the least interested by how these assets and liabilities are utilised by the investees. Within the theoretical context highlighted above, in our experience, we came across a fair value determination through a DCF (discounted cash flow) by a PE (Private Equity) fund (an IE) on an investment (also an IE) that, in turn, had the unquoted loan receivable with an embedded option from a related company. The embedded option permitted the receivable to be converted into shares in yet another related company that owned a plantation. The PE’s fair value determination thus had to include another expert’s valuation of the plantation for the estimation of the option value through the Black-Scholes model. In the days before the amendments to IFRS 10, IFRS 12 and IAS 27, the instrument above would have been consolidated at the PE level with assets and liabilities of the IE (including the fair value of the convertible loan receivable).

Therefore, the gross assets and gross liabilities of the combined entity are now simply presented as a net figure of the investee IE with a more conscious assessment of its fair value and greater disclosures of the rationale, techniques and parameters of the inputs of the valuation model or technique. Thus, it may be argued that the amendments require more effort and time for the preparation of these disclosures which, however, are now more useful and transparent. However, according to some, all of the above ‘benefits’ for an IE could be offset by the issues faced in stating the investments at fair value. This is aggravated by the fact that the fund managers’ remuneration in the form of management fees and performance fees is tied to the fair value of the IE/ investments.

In the instance of the PE and venture capital (“VC”) industry, the competitiveness to attract capital from desirable limited partners (“LP”) by the general partners make the fair value even more important. What then are the issues faced and costs incurred by an IE in recording their investments at fair value? IFRS 13 defines fair value as “the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.”8 Like ASC 820, IFRS 13 also sets out a three-level hierarchy that categorises the inputs to valuation techniques used to measure fair value. Highest priority is given to quoted (unadjusted) prices in active markets at Level 1 and lowest priority to unobservable inputs at Level 3.9 To record investments in financial assets using quoted market prices or Level 1 inputs may look straightforward, but critics have challenged that holders of Level 1 investments could also be overstating the fair value when the whole or a significant block of interests are to be sold at the quoted price. The usual trading capacity of the listed security may not be sufficient to allow such large interests to be transacted at the bid price. Such liquidity adjustment should be allowed but IFRS 13 currently does not allow such Level 1 adjustment.

It is also debatable whether the valuation of Google, for example, looked more transparent the day after it went public when Level 1 inputs were used instead of Level 3 inputs the day before.10 The difficulty in determining the fair value increases when the IE uses Level 3 or unobservable inputs through valuation techniques or models used by the IE or its third party valuation specialists. Typically, such models include many assumptions and parameters. For instance, a discounted cash flow projection (DCF) often used as such a valuation model is vulnerable to manipulation where a slight change of revenue growth, earnings estimate or the discount rate could change the fair value by millions of dollars.

However, this is partially addressed by IFRS 13’s disclosure requirement to provide narratives in the form of qualitative and quantitative sensitivity analyses on how changes in the unobservable or Level 3 inputs or parameters will have an impact on the fair value. Using our earlier example of the fair value determination through a DCF by the PE fund (an IE) of an investment (also an IE) that, in turn, has the unquoted convertible loan receivable above, the PE’s fair value determination now includes yet another expert’s valuation of the plantation and the estimation of the option value which has other unobservable (and sometimes unverifiable) inputs such as expected ‘strike/ exercise price’ (“at a certain discount to its market price”), volatility rate and risk-free rate. With such valuation techniques as described above and their ambiguity, are we still able to say that the fair value derived from Level 3 inputs is a price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date? Yes, we can, because while this price is theoretical and requires substantial judgement, it is not based on the assumption that the business or assets have to be sold in the near future or eventually or that it is a forced sale price. As long as the IE or its agent can consistently articulate, through adequate disclosures in the financial statements (including sensitivity analyses), how the fair value from a valuation model that uses Level 3 inputs is derived and explains the rationale, we think the IE or its agent would have satisfied the spirit of fair value accounting and that of IFRS 13. . As for all other entities, it would be beneficial also to the IE to review the robustness of its model and to fine-tune it such that the resultant fair value is regularly compared with the macroeconomic data and general market trends, and to compare with recent transactions including the last round of financing (LRF) transactions. We also witnessed how fund management clients in the PE/ VC industry have benefited from the above valuation process which, in a way, forced the fund managers to document and think through the assumptions and parameters to ensure the fair value was appropriately determined. Some fund managers would even include the valuation process review as part of their periodic monitoring and reporting to enhance the investors’ confidence more effectively than through extensive policies and procedures. If done well, the exercise is just an extension of their daily monitoring, which is aligned to the funds’ strategic decision-making and includes exit strategies. In conclusion, it may appear that the IE is shortchanged initially in the sense that the savings from the exemption from consolidation are offset by the cost and resources incurred for the equally daunting tasks and process of fair value determination. However, if you look more in-depth, the users are better off, as they can now allocate capital to better-performing investments (and IE), be it through Level 1, Level 2 or Level 3 inputs. The valuation models or techniques are also now better documented and more robustly fine-tuned, and all these have brought about more informed participation of all stakeholders in critical decision-making.

A final note of caution is that this fair value concept must be better enhanced with greater involvement of investment entities’ stakeholders of, namely, the IE, the investors/LP (limited partnerships), auditors, regulators and valuation experts through more frequent interactions and in-depth participation coupled with enhancement to the model, disclosures and documentation, so that it continues to create value for users through more useful and transparent financial information. 3 IFRS 10, B85A 4 IFRS 10, Paragraph 27 5 IFRS 10, paragraph 28 6 IFRS 12, paragraph 9A 7 IFRS 10, paragraph 32 8 IFRS 13, paragraph 9 9 IFRS 13, paragraph 72 10 Hoffelder, Kathy, “Fair-Value Rule Seeks Clearer M&A Deals,” (5 April 2013) . An overview of the IASB’s Disclosure Initiative in ten questions and answers by Joelle Moughanni, RSM Over the years, there have been increasing calls for the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) to review the disclosure requirements in IFRS and develop a disclosure framework to ensure that information disclosed is more relevant to users and to reduce the burden on preparers. The increase in volume and complexity of financial disclosure has been drawing significant attention from not only IFRS financial statement preparers, but most importantly, from users of those financial statements. ‘Disclosure overload’ and ‘cutting the clutter’ have become a priority issue for standard setters, regulatory bodies and, in particular, the IASB. The problem of disclosure overload is not unique to IFRS; a number of other standard setters and regulators are currently undertaking projects on disclosure overload (e.g. the FASB in the USA) as there is a perception that current disclosure practices are ineffective in drawing the attention of the users to the most decision-useful information. This article, in ten simple Q&As, aims at shedding light on the disclosure problem and some possible solutions as currently explored by the IASB. 1. What is the disclosure problem and what are its main perceived causes? 2.

How could communication and structure of the disclosures be enhanced? There is no clear definition of the disclosure problem: while preparers of IFRS financial statements (preparers) are concerned about the financial reports getting bigger and bigger, users of IFRS financial statements (users) say that the reports are not giving them the information that they need. Both preparers and users agree that financial reports are an important communication tool whereby preparers want to tell their story and users want to hear that story. When deciding the format of financial statements, it is common practice to follow the structure of the notes that is suggested (not required though) by IAS 1 Presentation of Financial Statements. However, as disclosures increase in volume with the transactions and the requirements of accounting standards becoming more complex, alternative formats may better communicate the links between different pieces of information and more transparently reflect the financial position, performance and risks of the entity. Despite this absence of a formal definition of the disclosure overload issue, a few contributing factors have consistently emerged from the different discussions and debates among stakeholders (lack of professional judgement being applied when disclosing company information, poor organisation and structure of the financial reports, duplication of disclosures, boilerplate disclosures, disclosures that are not focused on the key issues and the emerging issues and what has changed, checklist approach, unclear standards, etc.) that can be grouped under three potential causes of the disclosure problem: ƒƒ poor communication of disclosures: the format/structure issue; ƒƒ not enough relevant information: the tailoring issue; and ƒƒ too much irrelevant information: the materiality issue. The following alternative format restructuring options (all permitted by IFRS and sometimes already adopted by certain entities) might offer ways to enhance an entity’s effectiveness in communicating financial information. However, each entity needs to consider its specific facts and circumstances, including the specific needs of its primary users, as well as jurisdictional limitations or restrictions: ƒƒ improving navigation through the financial statements (headers, cross-references, etc.); ƒƒ ordering the notes in reference to importance: presentation of the more important information upfront would make the communication of financial information more efficient; ƒƒ including an executive summary of the main disclosures before presenting the more detailed disclosures in accordance with IFRS (some may find though that, on the contrary, such practice adds clutter to the financial statements); and .

ƒƒ disclosing each of the significant accounting policies, judgements, estimates and assumptions within the relevant note, instead of the predominant practice of summarising all significant accounting policies in a single note at the beginning of the notes section in the financial statements, and listing all judgements, estimates and assumptions towards the end. 3. What is the issue with tailoring disclosures? Users, investors and analysts often say that disclosures are boilerplate and generic, and therefore do not provide decisionuseful information. Boilerplate disclosures not only fail to add value to the financial statements, but often reduce the overall transparency of the financial statements as they may draw attention away from the entity-specific information. Tailoring disclosures to the entity-specific facts and circumstances may not reduce the length of the financial statements, but it should reduce the clutter and thus enhance the usefulness of the financial statements. In particular, the significant accounting policies disclosure and the disclosure of sources of estimation uncertainty are two relevant areas to consider when exploring the potential for tailoring of information. In fact, non-applicable policies should not be disclosed and applied policies should be entity-specific in the sense that it should go beyond only repeating the relevant requirement of IFRS.

For instance, instead of simply disclosing that revenue from sale of goods is recognised when the criteria in IAS 18 Revenue are met, the entity should add information on how it determines whether the significant risks and rewards of ownership have been transferred to the customer. If disclosure of sources of estimation uncertainty is not sufficiently entity-specific, and/or if entities list all sources of estimation uncertainty without giving prominence to any that have a significant risk of resulting in material adjustments within a predictable future period, the usefulness of the disclosure is drastically reduced. In practice, most entities are complying with the form of the disclosure requirement, but not the substance of it, by listing over pages and pages sources of estimation uncertainty, without providing insight into which of them are more significant so that users need to be particularly aware of them. increase the effectiveness of disclosures. However, in the case where the required information is already provided elsewhere in a report that also contains the financial statements, crossreferencing might be an efficient tool to reduce duplication and improve the transparency of the overall document. In general, it would not be IFRS compliant to present disclosures required by the Standards outside the financial statements, even if appropriately incorporated by sufficient cross-reference… unless specifically allowed by the relevant Standard.

For example, IFRS 7 Financial Instruments: Disclosures allows certain information to be presented outside the financial statements as long as it is incorporated by crossreference from the financial statements to another statement, such as a management commentary or risk report that is available to users on the same terms and at the same time as the financial statements (IAS 34 Interim Financial Reporting is another example). To ensure that users are able to locate the required disclosure, a cross-reference must be sufficiently specific, not causing confusion about the consistency and completeness of the financial statements (including assurance provided by the external auditor). 6. What about the role of materiality? Many believe that the lack of appropriate application of the concept of materiality is a key contributor to the excessive disclosures in financial reports. If the concept of materiality was applied successfully, then immaterial information that clouds more relevant information would be removed, thus making the performance and the financial position of the entity more visible. The concept of materiality is key to preparing IFRS financial statements, in particular for users, as it impacts which information is considered relevant and is therefore presented in the financial statements.

However, the application of the concept of materiality requires significant judgement, which is inherently subjective, and there is currently limited guidance on its application. 4. Would disclosure of only non-mandatory policies or new policies be acceptable? When preparing their financial statements, entities are traditionally focused on ensuring that material information is not omitted, as current IFRS do not explicitly prohibit the provision of immaterial information in financial statements. However, the inclusion of irrelevant or immaterial information can obscure useful information in the financial statements. Although such an approach may have some merit for users that have sufficient experience with IFRS and knowledge of the mandatory policy requirements, an entity should consider the needs of the primary users who might have less experience with IFRS. In addition, disclosing only nonmandatory policies and new policies would not be appropriate under current IFRS, since IAS 1 requires the disclosure of a summary of (all) significant accounting policies applied by the entity. It is important also to bear in mind that materiality should not be assessed merely by comparison with the absolute or relative size of an amount: both quantitative and qualitative factors are relevant to all materiality decisions.

This is especially relevant for disclosures that mainly include verbal description, rather than numerical information, and may even be entirely qualitative. Basing the assessment of materiality only on the amounts involved is generally not appropriate for disclosures. 5. What about presentation of certain disclosures ‘somewhere else’ outside the financial statements? Irrelevant/immaterial information should be removed from the financial statements.

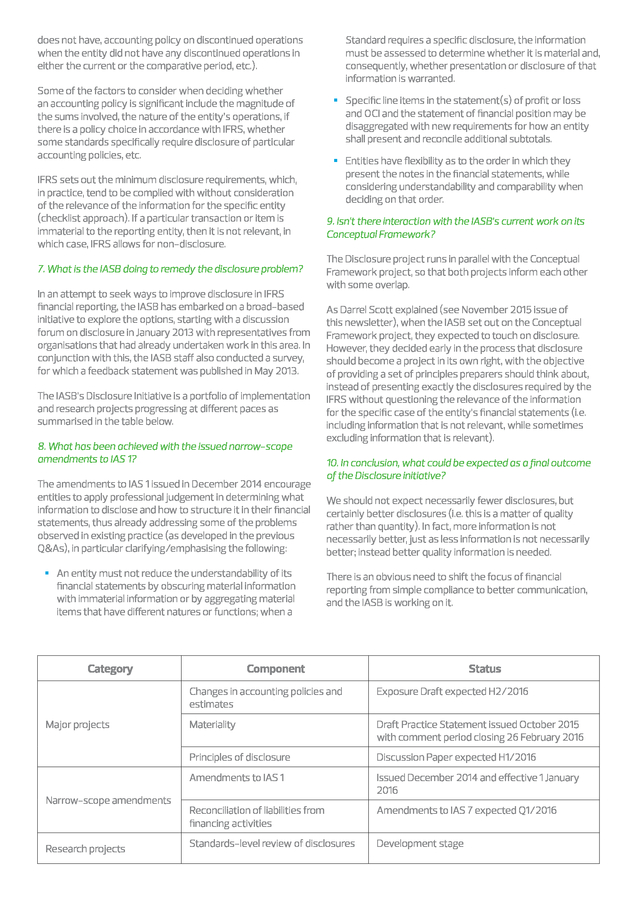

In particular, accounting policies that are not significant or relevant for an understanding of the entity’s financial statements are not required to be disclosed (e.g. accounting policies on financial instruments that the entity Presentation of certain disclosures outside the financial statements would not necessarily reduce the volume or . does not have, accounting policy on discontinued operations when the entity did not have any discontinued operations in either the current or the comparative period, etc.). Some of the factors to consider when deciding whether an accounting policy is significant include the magnitude of the sums involved, the nature of the entity’s operations, if there is a policy choice in accordance with IFRS, whether some standards specifically require disclosure of particular accounting policies, etc. IFRS sets out the minimum disclosure requirements, which, in practice, tend to be complied with without consideration of the relevance of the information for the specific entity (checklist approach). If a particular transaction or item is immaterial to the reporting entity, then it is not relevant, in which case, IFRS allows for non-disclosure. 7. What is the IASB doing to remedy the disclosure problem? In an attempt to seek ways to improve disclosure in IFRS financial reporting, the IASB has embarked on a broad-based initiative to explore the options, starting with a discussion forum on disclosure in January 2013 with representatives from organisations that had already undertaken work in this area. In conjunction with this, the IASB staff also conducted a survey, for which a feedback statement was published in May 2013. The IASB’s Disclosure Initiative is a portfolio of implementation and research projects progressing at different paces as summarised in the table below. 8.

What has been achieved with the issued narrow-scope amendments to IAS 1? The amendments to IAS 1 issued in December 2014 encourage entities to apply professional judgement in determining what information to disclose and how to structure it in their financial statements, thus already addressing some of the problems observed in existing practice (as developed in the previous Q&As), in particular clarifying/emphasising the following: ƒƒ An entity must not reduce the understandability of its financial statements by obscuring material information with immaterial information or by aggregating material items that have different natures or functions; when a Category Standard requires a specific disclosure, the information must be assessed to determine whether it is material and, consequently, whether presentation or disclosure of that information is warranted. ƒƒ Specific line items in the statement(s) of profit or loss and OCI and the statement of financial position may be disaggregated with new requirements for how an entity shall present and reconcile additional subtotals. ƒƒ Entities have flexibility as to the order in which they present the notes in the financial statements, while considering understandability and comparability when deciding on that order. 9. Isn’t there interaction with the IASB’s current work on its Conceptual Framework? The Disclosure project runs in parallel with the Conceptual Framework project, so that both projects inform each other with some overlap. As Darrel Scott explained (see November 2015 issue of this newsletter), when the IASB set out on the Conceptual Framework project, they expected to touch on disclosure. However, they decided early in the process that disclosure should become a project in its own right, with the objective of providing a set of principles preparers should think about, instead of presenting exactly the disclosures required by the IFRS without questioning the relevance of the information for the specific case of the entity’s financial statements (i.e. including information that is not relevant, while sometimes excluding information that is relevant). 10. In conclusion, what could be expected as a final outcome of the Disclosure initiative? We should not expect necessarily fewer disclosures, but certainly better disclosures (i.e.

this is a matter of quality rather than quantity). In fact, more information is not necessarily better, just as less information is not necessarily better; instead better quality information is needed. There is an obvious need to shift the focus of financial reporting from simple compliance to better communication, and the IASB is working on it. Component Status Changes in accounting policies and estimates Research projects Draft Practice Statement issued October 2015 with comment period closing 26 February 2016 Discussion Paper expected H1/2016 Amendments to IAS 1 Narrow-scope amendments Materiality Principles of disclosure Major projects Exposure Draft expected H2/2016 Issued December 2014 and effective 1 January 2016 Reconciliation of liabilities from financing activities Amendments to IAS 7 expected Q1/2016 Standards-level review of disclosures Development stage . We commented on IASB’s recent proposals for: Clarifications to IFRS 15 What is the current status of the project? The exposure draft ED/2015/6 Clarifications to IFRS 15 (‘the ED’), issued on 30 July 2015, aims at aiding the transition to the new revenue Standard by adding practical expedients, and clarifying how to identify the performance obligations in a contract, to determine whether a party to a transaction is the principal or the agent, and to determine whether a licence provides the customer with a right to access or a right to use the entity’s intellectual property. Comments on the ED were requested by 28 October 2015. What did RSM say on the ED? Overall, we supported the proposed amendments to IFRS 15 as the clarifications would reduce diversity in practice on implementation of the requirements in the new revenue Standard. In particular: ƒƒ In relation to identifying performance obligations, we agreed with the IASB’s decision not to modify the Standard itself and with the proposed amendments to the accompanying Illustrative Examples. ƒƒ We agreed with the proposed clarifications to the guidance on principal versus agent considerations, as they help to clarify the application of the control principle by the entity and are consistent with the concept of then transferring that control to the customer. In addition, the explicit reference now to “the specified” goods and services is helpful in distinguishing between performance obligations of the entity and the goods and services which are to be provided to the customer particularly when this will be by another party. ƒƒ We agreed with the proposed amendments regarding licensing as they improve the operability and understandability of the guidance. ƒƒ We agreed with the proposed transition relief for modified contracts and completed contracts. View the full comment letter here Although we agreed with the proposal not to amend IFRS 15 with respect to collectability, measuring non-cash consideration and the presentation of sales taxes, we recommended that the IASB considers in the near future undertaking a separate comprehensive project on non-cash considerations due to potential different interpretations in practice. Finally, although we encourage the IASB and FASB to keep IFRS 15 and Topic 606 as converged as possible, we anticipate possible further differences between the two Standards will emerge from the continuing discussions at the Transition Resource Group (TRG) in particular.

Therefore, we recommended that ‘Comparison of IFRS 15 and Topic 606’ (Appendix 1 to the Basis for Conclusions on IFRS 15) is kept up to date as a reliable summary of the differences. . We commented on IASB’s recent proposals for: Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting What is the current status of the project? The exposure draft ED/2015/3 Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting (‘the ED’), issued on 28 May 2015, aims at enhancing financial reporting by providing a more complete, clearer and updated set of concepts that can be used by both the IASB when it develops IFRS, and others to help them understand and apply those Standards. Comments on the ED were requested by 25 November 2015. What did RSM say on the ED? Overall, we welcomed the proposals in the ED addressing guidance that is missing or insufficient in the current Conceptual Framework (such as measurement bases, presentation and disclosure, etc.). While we broadly agreed with the content of the ED, we disagreed with some of the proposed solutions. In particular: ƒƒ We are not in favour of reintroducing an explicit reference to the notion of prudence to support the meaning of neutrality.

Instead, we agreed with the alternative view that financial information possessing the characteristic of neutrality is already free from bias, and that reinstating prudence would on the contrary introduce bias and confusion. ƒƒ We believe that the proposed description and boundary of a reporting entity are not sufficiently clear (e.g. when the reporting entity is not a legal entity). ƒƒ Although we broadly agreed with the proposed approach to recognition, we are concerned that the guidance proposed is insufficient to ensure consistent standardsetting, in particular, when recognising an asset where there is existence uncertainty or a low probability of an inflow would not result in relevant information. ƒƒ In our view, more discussion and explanation of the need for different measurement bases to be used for the statement of financial position and the statement of profit or loss is required. View the full comment letter here ƒƒ We believe that the business model concept should be taken into account in financial statements for their relevance and faithful representation, because it provides insights into how the entity’s business activities are managed. In addition, we reiterated our disappointment (expressed in our 14 January 2014 comment letter to the Discussion Paper DP/2013/1 A Review of the Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting ‘the DP’) that the ED fails to define clearly what “profit or loss” and “other comprehensive income” are, in particular, their respective differentiating characteristics, i.e. what distinguishes items of income and expense that are recognised in profit or loss from those recognised in OCI, and why the distinction is necessary to provide faithful representation? Similarly, we still do not find robust principles and rationale behind the “recycling versus no-recycling” concept.

We did not agree with the proposed rebuttable presumption of reclassification. In the absence of overarching principles, deciding if and when reclassifying items of income and expenses included in OCI into the statement of profit or loss enhances the relevance of the information included in the statement of profit or loss for a future period is somewhat arbitrary. Also, as expressed in our comment letter on the DP, we are supportive of the arguments against recycling. .

We commented on IASB’s recent proposals for: Updating References to the Conceptual Framework (Proposed amendments to IFRS 2, IFRS 3, IFRS 4, IFRS 6, IAS 1, IAS 8, IAS 34, SIC-27 and SIC-32) What is the current status of the project? The exposure draft ED/2015/4 Updating References to the Conceptual Framework (Proposed amendments to IFRS 2, IFRS 3, IFRS 4, IFRS 6, IAS 1, IAS 8, IAS 34, SIC-27 and SIC-32) (‘the ED’), issued on 28 May 2015, aims at updating references to the Conceptual Framework in existing IFRS. Comments on the ED were requested by 25 November 2015. What did RSM say on the ED? We would agree with amendments that are of an editorial nature only. In fact, we welcome editorial changes for the use of consistent terms and concepts in all the IFRS to ensure their consistent application. However, in our opinion, the implications of the proposed changes are not clear and we are concerned about possible unintended consequences of the proposed amendments. We recommended that a more detailed analysis be performed for each proposed amendment in order to understand the impact of the proposed amendments and to assess their practicability.

In particular, we believe that outreach activities should be conducted to assess and report the likely effects of using the Conceptual Framework in developing policies under IAS 8. Therefore, and until a more detailed analysis of the potential impact of these proposed amendments is available, we believe that the proposed changes in the exposure draft Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting should be incorporated into existing IFRS only if they do not trigger any accounting change. View the full comment letter HERE We were unable to comment on the proposed effective date and transition provisions before understanding the impact of the proposed amendments on the accounting. We do not see why amendments of only editorial nature (i.e. without changes to the accounting requirements) would require transition provisions.

In our view, for the sake of consistency, early application should not be permitted on a Standard-byStandard basis. . We commented on IASB’s recent proposals for: Effective Date of Amendments to IFRS 10 and IAS 28 What is the current status of the project? The exposure draft ED/2015/7 Effective Date of Amendments to IFRS 10 and IAS 28 (‘the ED’), issued on 10 August 2015, aims at deferring indefinitely the effective date of the narrow-scope amendments to IFRS 10 and IAS 28 Sale or Contribution of Assets between an Investor and its Associate or Joint Venture – issued in September 2014 and applicable to transactions occurring in annual periods beginning on or after 1 January 2016 (‘the September 2014 Amendment’) – until such time as it has finalised amendments that might result from its research project on the equity method, although earlier application would continue to be permitted. Comments on the ED were requested by 9 October 2015. What did RSM say on the ED? We supported the IASB’s proposal to defer indefinitely the effective date of the September 2014 Amendment until such time as the Board has finalised any amendments that result from its research project on the equity method. We are of the opinion that the deferral will give the IASB the opportunity to address the application problems arising from the equity method requirements set out in IAS 28 Investments in Associates and Joint Ventures in a comprehensive way and in a single project, and entities will not need to change the way in which they apply IAS 28 twice in a short period of time. We agreed also that early application of the September 2014 Amendment should continue to be permitted, as it is unlikely to increase existing diversity in practice. View the full comment letter HERE . We commented on IASB’s recent proposals for: Remeasurement on a Plan Amendment, Curtailment or Settlement/Availability of a Refund from a Defined Benefit Plan (Proposed amendments to IAS 19 and IFRIC 14) What is the current status of the project? The exposure draft ED/2015/5 Remeasurement on a Plan Amendment, Curtailment or Settlement/Availability of a Refund from a Defined Benefit Plan (Proposed amendments to IAS 19 and IFRIC 14) (‘the ED’), issued on 18 June 2015, aims at improving information to investors and addressing some diversity in practice in relation to pension accounting requirements, in particular, when a defined benefit plan is amended, curtailed or settled during a reporting period (IAS 19), and how the powers of other parties (e.g. the Trustees of the plan) affect an entity’s right to a refund of a surplus from the plan (IFRIC 14). Comments on the ED were requested by 19 October 2015. What did RSM say on the ED? Overall, we supported the proposed amendments as we believe that they will result in less divergence in practice, enhanced understandability, and the provision of more relevant and useful information. In particular: ƒƒ The plan trustees and other parties who can use the plan surplus for other purposes that change the benefits for plan members without the entity’s consent prevent the availability of a refund of the surplus from being recognised as a plan asset. ƒƒ Trustees’ or other parties’ unconditional power to wind up the plan or make a full settlement, at any time without the entity’s consent, prevents the gradual settlement over time until all members have left the plan, and thus restricts an entity’s ability to realise economic benefits through a gradual settlement. ƒƒ We agreed with the IASB’s conclusion that the power to buy annuities as plan assets or make other investment decisions relates to the future amount of plan assets but does not relate to the right to a refund of a surplus. Consequently, such power, on its own, would not prevent the entity from recognising a surplus as an asset. View the full comment letter HERE ƒƒ At the end of the reporting period, and when a plan amendment, curtailment or settlement occurs, an entity should determine the availability of a refund or a reduction in future contributions in accordance with the contractually agreed conditions of the plan, constructive obligations and substantively enacted statutory requirements. ƒƒ The asset ceiling should not affect the measurement and recognition of past service cost or a gain or loss on settlement at the time of the event, and after a plan amendment, curtailment or settlement, the asset ceiling should be determined using the updated surplus and updated actuarial assumptions including the discount rate.

Thus, recognising past service cost or a gain or loss on settlement and assessing the asset ceiling are two distinct steps. ƒƒ An entity should determine the current service cost and net interest for the remaining portion of the period by using the updated assumptions used in the most recent measurement required by paragraph 99 of IAS 19. ƒƒ The limited retrospective application of the proposals enhances comparability of financial information provided and based on cost vs benefit considerations. . We focused on: using discounted cash flow models for impairment testing under IAS 36 What is the issue? Company XYZ is seeking advice as to whether and how discounted cash flow models can be used to calculate fair value less costs of disposal of cash-generating units? What is the proposed solution? IAS 36 Impairment of Assets requires the carrying amount of a cash-generating unit (CGU) to be compared with the higher of its value in use (VIU) and fair value less costs of disposal (FVLCD––). Usually, discounted cash flow models are used to determine VIU, but they can be used also to calculate FVLCD. FVLCD is based, ideally, on transaction prices observed in the market for comparable assets. Where transaction prices are not available, a discounted cash flow (DCF) calculation is used to determine FVLCD. However, in practice, VIU and FVLCD often provide different results even if both are determined using a discounted cash flow model, because of different inputs to the model.

This is due in particular to the following: ƒƒ VIU is a pre-tax concept and reflects entity-specific synergies. However, there are significant restrictions on what can be included in the forecast cash flows. In particular, future capital expenditure that enhances the CGU’s performance, and the resulting increases expected in net cash flows, cannot be included in the calculation, even if budgeted by management.

Also, the costs and benefits of a restructuring plan cannot be included unless the IAS 37 criteria have been met. ƒƒ FVLCD is a post-tax concept that reflects market participants’ views of the value of the CGU. The cash flows used in the VIU calculation are based on management’s most recent approved financial budgets/ forecasts. The assumptions used to prepare the cash flows should be based on reasonable and supportable assumptions, representing management’s best estimate of the economic circumstances that will prevail over the remaining life of the CGU. The assumptions used by management should usually be supported by market evidence (e.g.

by benchmarking against market data), and it might be necessary to adjust the assumptions where they cannot be supported by market evidence. They should also be the assumptions that are applicable at the date of assessment. The assumptions and other inputs used in a DCF model for FVLCD should incorporate observable market inputs as much as possible. The cash flows to be used in a DCF prepared to determine FVLCD might well be different from those in a VIU calculation.

The valuation technique used in determining FVLCD should incorporate assumptions that market participants would use in estimating the CGU’s fair value, such as revenue growth, profit margins and exchange rates. FVLCD in many cases will provide a higher recoverable amount than VIU, because FVLCD does not have the automatic prohibition on including enhancement capital expenditure and restructurings in the DCF. The cash flow projections can include the effect of future restructurings only if market participants would be expected to undertake these in order to extract the best value from the CGU. . Global Contacts Americas Middle East Richard Stuart T +1 203 905 5027 E richard.stuart@rsmus.com Chandra Sekaran T +965 2245 2680 E chandra.sekaran@rsm.com.kw Europe Africa Nicky Warburton T +44 1772 216000 E nicky.warburton@rsmuk.com Simon Fisher T +254 20 4451747/8/9 E sfisher@rsm-ea.com Asia Pacific RSM Global Executive Office – UK Jane Meade T +61 2 8226 9518 E jane.meade@rsm.com.au Ellen O’Sullivan T +44 20 7601 1080 E ellen.osullivan@rsm.global Editor Dr Marco Mongiello ACA Deputy Head of School Executive Director MBA and MSc Programmes Surrey Business School T +44 01483 683995 E m.mongiello@surrey.ac.uk The publication is not intended to provide specific business or investment advice. No responsibility for any errors or omissions nor loss occasioned to any person or organisation acting or refraining from acting as a result of any material in this publication can be accepted by the authors or RSM International. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily that of RSM International. You should take specific independent advice before making any business or investment decision. RSM is the brand used by a network of independent accounting and advisory firms each of which practices in its own right. The network is not itself a separate legal entity of any description in any jurisdiction.

The network is administered by RSM International Limited, a company registered in England and Wales (company number 4040598) whose registered office is at 11 Old Jewry, London EC2R 8DU. The brand and trademark RSM and other intellectual property rights used by members of the network are owned by RSM International Association, an association governed by article 60 et seq of the Civil Code of Switzerland whose seat is in Zug. © RSM International Association, 2016 .

To this end, I am grateful to Dr Nigel Sleigh-Johnson, Head of the Financial Reporting Faculty at ICAEW and co-author of ‘Moving to IFRS reporting: seven lessons learned from the European experience’, for sharing his personal views with us. With one eye on his publication and the other on my first question, which is about his insights into the next decade, Nigel starts in a very positive way: NSJ: The progress we have experienced in the past ten years is remarkable. While we are not going to see an easy journey towards universal accounting standards, there are very good signs of incremental change. I have just been in Japan and the interest in moving towards the adoption of IFRS is tremendous. I recently met the chairman of the Indonesian accounting standard setters, who too showed a commitment towards the adoption of IFRS. They do have different paths towards adoption.

They have different challenges and the timetables are not always clear. However, I think that those who are looking at the lessons learnt from the European experience find very positive messages. And, of course, the lessons do not come just from Europe, there are other countries too, for example, Australia, South Korea and South Africa. The story is different in each case, but what they all have in common is that they are moving in the right direction.

For example, in India they have a conversion process, where the deadlines moved several times. Nevertheless, the Indian commitment in moving in the direction of IFRS reporting is there. Similarly, we see the same commitment in China, where they are very close to a full convergence plan.

There are still differences, but there is no doubt that Chinese accounting standards are close to IFRS. In terms of the US, that remains a real challenge. It is very significant and encouraging that the SEC has permitted foreign companies to file accounts using IFRS without reconciliation. As the SEC is one of the largest IFRS regulators in the world and the US is one of the largest economies and capital markets in the world, the convergence achieved is very significant.

The US interest in moving towards IFRS remains a long term ambition though, because the US has a very strong tradition of accounting and a distinctive regulatory and legal environment. I feel encouraged by the comments that the SEC Chief Accountant, James Schnurr, made in December 2014, when he was relatively new in the job. He talked about allowing US domestic registered companies to publish information using IFRS, alongside US GAAP filings, without reconciliation. He touched on that again in other public talks in May and in September 2015. So, although we are not going to see a switch to IFRS in the US any time soon, nevertheless this idea of non-reconciliation is potentially a major concession. One current concern with converged standards like IFRS 15, is the likelihood that we will see the SEC and other US bodies issue reams of amendments and guidance to solve interpretation challenges. On this note, a slight worry is that other jurisdictions, like Japan, which have a rules-based approach similar to the US, are looking with some interest at these forthcoming amendments and guidance, creating the possibility of a new layer of IFRS interpretative material in those jurisdictions. MM: Will this lead to major adaptations in the adoption processes of jurisdictions that are new to IFRS? Is there a danger that large economies like China or India may look at the European endorsement process and, imitating its principle, end up making significant changes to the IFRS when adopting them? .

NSJ: One of the lessons that emerged from the study of the past decade of IFRS implementation in Europe is that the endorsement and adoption process has so far almost invariably resulted in full endorsement. It is, however, very tempting for governments to make significant changes. This is why we need to promote an understanding of the drawbacks of doing this. When I was in Japan recently, I spoke with Japanese regulators in these terms.

We are currently doing so in other countries like Indonesia, and we are not the only ones disseminating this message. In fact, the debate about IFRS started in the early 70’s; it has taken decades to reach the point where we are now and the debate is still ongoing. Taking a historical perspective, 100 years is not a long period of time, let alone a decade. So, as much as I would like to live long enough to see IFRS adopted universally, I am not sure this will happen! In the meantime, there will be an emergence of different dialects of the international language of accounting, which will bring a basis for common understanding. There is not any easy global analogy to be drawn here; having a set of standards issued by a single private organisation and being adopted globally has never happened and we cannot predict the outcome.

It is nevertheless extraordinary what has been achieved so far; jurisdictions around the world adopting IFRS is a huge step forward, which can only improve global prosperity and stability. Financial reporting is, after all, an economic fundamental. There has also been great progress in the direction of exchanging information and networking among standard setters around the world. There is a lot more to be done, though, in terms of coordination with countries that are now approaching IFRS. If you look back at 2005, there has been a tremendous transformation and I like to think that one instigator of this change is ICAEW, which has played an important role in the development of IFRS since their initial conception in the 70’s, providing independent and unbiased contributions to the IFRS debate.

The key for us [ICAEW] in all of this has always been to promote the public interest. MM: Speaking about public interest, there are interesting developments in international reporting, which are very effectively championed by the International Integrated Reporting Council1 and their proposed approach to reporting that integrates financial, social, environmental and other aspects of companies’ impact and performance in one place. Is this contradicting the efforts towards reducing the length of the annual reports? NSJ: It is a complex situation. Business transactions have become much more complex over time. You have to ensure that the information is available for investors using it to form their judgements, but you can certainly go too far in trying to tackle complexity.

Nonetheless, it is very important for the IASB to acknowledge the need to make the standards as clear as possible, still always keeping in mind the overarching principle of cost/benefit in reporting. A good example is the enormous complexity of the old draft standard for leasing; the message has certainly been heard and the new standard on leasing in its final form has gone through a massive simplification. On the other hand, you are never going to eliminate complexity from financial reporting.

Discussions have taken place, particularly through the Lab2, where investors and preparers provide very different answers to the challenges and needs of reporting, but everyone agrees on writing and signposting more clearly. There are remarkable examples of listed companies large and small that report in an easy-to-follow way, even though their businesses may be complex. Especially if you look at the front end of the accounts, the ideas of better reporting of strategy and KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) have been around for a long time, but now they are coming to fruition in a more joined-up way, providing a very clear picture of where the company is, where it is heading and what its challenges are. I was very impressed by some of the smaller quoted companies’ reports I have reviewed recently. To your question, if you have improvements at the front end, consistency throughout, the IASB keeping complexity to a 1 Editor’s note: we reported about IIRC in the newsletter in issue 23 Editor’s note: the Lab is an initiative of the FRC, whose inception was reported in the newsletter in issue 12, which brings together users and preparers of companies’ accounts to debate and propose mutually beneficial developments in reporting. 2 .

minimum and an acceptance that accounts are not going to become much shorter – these are ways of improving annual reports. The IIRC has an even wider view of integration in corporate reports; and there are, of course, demands for major companies to be more accountable in many ways (environmental impact, taxation, social impacts and so on). It is a good thing that there are movements to encourage greater transparency and accountability. However, we do have a view at ICAEW that it is important not to clutter the traditional annual reports and accounts with regulatory requirements that are not primarily directed to the information needs of investors.

So, one can see improvements taking place within UK annual reports, but we are going to see integrated annual reporting developing in different ways around the world, depending on existing frameworks and cultures in different jurisdictions; in some jurisdictions mandating integrated reporting may be the most effective way of encouraging people to apply it, in others, like the UK, where the annual report is well developed and generally informative, mandating would not be helpful. MM: So, what are your predictions for the next ten years? NSJ: Taking the perspective of the next ten years, I think that the future of IFRS presents challenges that are as great as those of the past ten years. In a sense, phase one has been completed successfully, but it is one of many phases on a journey towards global reporting. There is a huge amount to aim for and there are very good signs that we will make substantial progress over the next ten years, but this must be coupled with recognition that things are unpredictable in many ways.

For example, we cannot be sure of the direction in which the US will move. The world is a tremendously diverse place and although there are trends towards globalisation, there are strong traditions and cultures which we are not going to overturn in our lifetime. Hence, although I believe that there will always be a degree of diversity in interpretations, what we have achieved in the first ten years is a huge step forward and puts us on a good path for the next ten years. MM: We talk about the challenges of globalisation because of differences in jurisdictions’ cultures and regulations, but another aspect of the challenge is the differences in sectors and industries – in particular, new high-tech and highly innovative companies.

With regard to some of these companies, investors are no longer interested in looking at traditional measures like the operating profit or gross profit. Take the examples of Tesla Motors, LinkedIn and Facebook, where investors are not looking at the same ratios as they would for more traditional companies in established industries. Should IFRS suggest sets of KPIs that may be more useful for different companies? . NSJ: I think that this is an important area that calls for different stakeholders to come together and discuss a solution. Having some sort of forum to achieve that would be tremendously beneficial. I am not sure that including KPIs in IASB’s Standards is the right answer, though. However, a wider group of stakeholders could potentially agree on relevant KPIs for particular sectors.

Initiatives in this area would be very sensible; this could indeed be a theme of the next ten years. In this debate, we, at ICAEW, tend to think that the IASB should not be writing different standards for different sectors. It should be possible to establish principles and concepts that can apply to all reporting entities. This is achieved by principles being tested across widely different sectors during the development of a standard to ensure they can be applied consistently and without practical difficulties across sectors. On the other hand, major companies tend, in practice, to keep a close eye on each other’s annual reports, which should create and promote not just a degree of consistency but even some convergence of industry norms. In some circumstances at least, companies in the same sectors talk to each other to exchange views on reporting; this is terribly healthy and there is a case for doing more in this direction.

Perhaps exploring accounting norms for specific sectors is something to be debated during the next phase. I’d just add, though, that the companies you mention are still start-ups or fairly young, so they either haven’t made a profit yet or their current profits are not what investors hope to see from them in the future. I don’t think in those circumstances it’s just about sectorial issues. MM: To those (if there still is anyone) who say that accounting and reporting is all about the past, Nigel SleighJohnson’s words will be eye opening. For the majority of us, I am sure, they come as an inspiring call to renew our energy and passion for global accounting and reporting because the past ten years are nothing but the very beginning of an exciting, long journey. .

Are investment funds shortchanged by the exemption from consolidation with more efforts and disclosures required by fair value accounting? By Chee Wee Lock, Partner and Industry Leader of Professional & Business Services Vertical Industry Group, RSM Singapore ƒƒ commits to its investors that its business purpose is to invest funds solely for returns from capital appreciation, investment income or both; and Amendments to IFRS 10, Consolidated Financial Statements, IFRS 12, Disclosure of Interests in Other Entities and IAS 27, Separate Financial Statements on Investment Entities (IE) provide an exemption from consolidation for investment funds and similar entities. As such, an IE records its investments in subsidiaries at fair value through profit or loss, instead of consolidating them. The main reason for such preferential treatment is that the IE operates in a unique business model where fair value information is provided to its users and such fair value information is more useful for the stakeholders within the IE’s ecosystem. However, the assessment whether an entity qualified as an IE is not straightforward.

Let us explore closely. ƒƒ measures and evaluates the performance of substantially all of its investments on a fair value basis.” First, the assessment needs to consider all facts and circumstances such as the purpose and design of the entity. Before we can do such consideration, let us understand the definition of an IE. An IE is3 4 “an entity that: ƒƒ obtains funds from one or more investors for the purpose of providing those investors with investment management services; If it is apparent from its corporate documents or offering memorandum that the purpose of the entity is to solicit funds from its investor or investors and to invest them solely to gain from capital appreciation or investment income, then the entity can be an IE. Conversely, if an entity states to its investors that it is making an investment to develop, manufacture or promote products with its investees, it appears its business purpose is inconsistent with that of an IE. After the IE meets all the essential elements of the definition of IE, it then needs to have one or more of the following typical characteristics5: ƒƒ holds more than one investment; ƒƒ has more than one investor; ƒƒ has investors that are not the IE’s related parties; and ƒƒ has ownership interests in the form of equity or similar interests. .

Even when it does not have all the typical characteristics, management may still judge that the entity is nonetheless an IE, although a disclosure of such management judgement is required. A further requirement is that an IE’s6 subsidiary that provides investment-related services (such as advisory, investment management and administrative support) will be required to be consolidated by the IE7. It may seem that the IE would benefit from cost and time savings when it is provided an exemption from consolidation. Also, it would appear that users of financial statements can now better assess the financial position, performance and cash flows of the IE, instead of using consolidated financial statements that also comprise of the investees’ figures. As such, more meaningful and useful information could now be obtained by investors of the IE since fair value is what they are interested in, together with income and capital appreciation.

These investors are not interested in (and no longer bother with) the line-by-line consolidation of the investees’ assets and liabilities as they have no title to these assets, have no obligation to these liabilities and are not the least interested by how these assets and liabilities are utilised by the investees. Within the theoretical context highlighted above, in our experience, we came across a fair value determination through a DCF (discounted cash flow) by a PE (Private Equity) fund (an IE) on an investment (also an IE) that, in turn, had the unquoted loan receivable with an embedded option from a related company. The embedded option permitted the receivable to be converted into shares in yet another related company that owned a plantation. The PE’s fair value determination thus had to include another expert’s valuation of the plantation for the estimation of the option value through the Black-Scholes model. In the days before the amendments to IFRS 10, IFRS 12 and IAS 27, the instrument above would have been consolidated at the PE level with assets and liabilities of the IE (including the fair value of the convertible loan receivable).

Therefore, the gross assets and gross liabilities of the combined entity are now simply presented as a net figure of the investee IE with a more conscious assessment of its fair value and greater disclosures of the rationale, techniques and parameters of the inputs of the valuation model or technique. Thus, it may be argued that the amendments require more effort and time for the preparation of these disclosures which, however, are now more useful and transparent. However, according to some, all of the above ‘benefits’ for an IE could be offset by the issues faced in stating the investments at fair value. This is aggravated by the fact that the fund managers’ remuneration in the form of management fees and performance fees is tied to the fair value of the IE/ investments.