M&A Report - Determining the Likely Standard of Review Applicable to Board Decisions in Delaware M&A Transactions (February 2016 Update) - February 8, 2016

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher

Description

February 8, 2016

M&A REPORT - DETERMINING THE LIKELY STANDARD OF REVIEW

APPLICABLE TO BOARD DECISIONS IN DELAWARE M&A

TRANSACTIONS (FEBRUARY 2016 UPDATE)

To Our Clients and Friends:

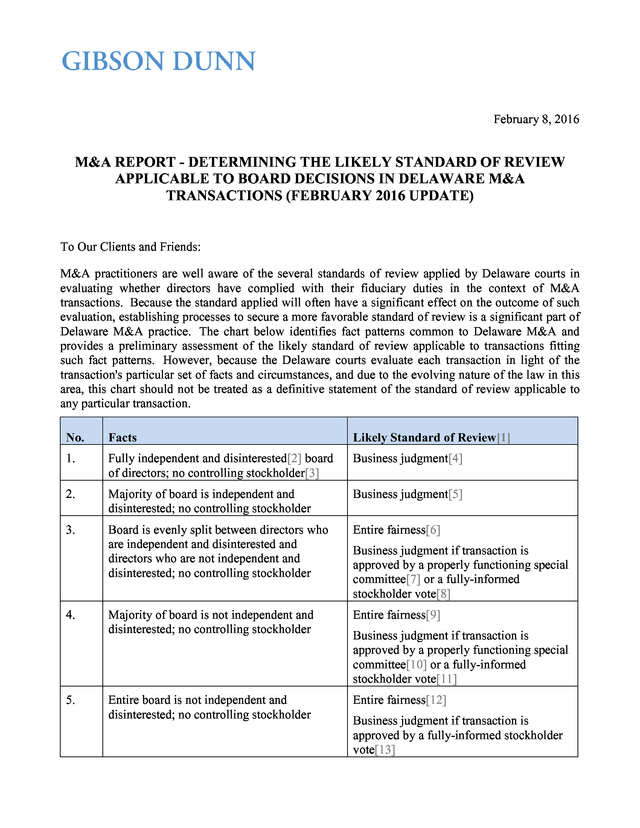

M&A practitioners are well aware of the several standards of review applied by Delaware courts in

evaluating whether directors have complied with their fiduciary duties in the context of M&A

transactions. Because the standard applied will often have a significant effect on the outcome of such

evaluation, establishing processes to secure a more favorable standard of review is a significant part of

Delaware M&A practice. The chart below identifies fact patterns common to Delaware M&A and

provides a preliminary assessment of the likely standard of review applicable to transactions fitting

such fact patterns. However, because the Delaware courts evaluate each transaction in light of the

transaction's particular set of facts and circumstances, and due to the evolving nature of the law in this

area, this chart should not be treated as a definitive statement of the standard of review applicable to

any particular transaction.

No.

Facts

Likely Standard of Review[1]

1.

Fully independent and disinterested[2] board

of directors; no controlling stockholder[3]

Business judgment[4]

2.

Majority of board is independent and

disinterested; no controlling stockholder

Business judgment[5]

3.

Board is evenly split between directors who

are independent and disinterested and

directors who are not independent and

disinterested; no controlling stockholder

Entire fairness[6]

Majority of board is not independent and

disinterested; no controlling stockholder

Entire fairness[9]

Entire board is not independent and

disinterested; no controlling stockholder

Entire fairness[12]

4.

5.

Business judgment if transaction is

approved by a properly functioning special

committee[7] or a fully-informed

stockholder vote[8]

Business judgment if transaction is

approved by a properly functioning special

committee[10] or a fully-informed

stockholder vote[11]

Business judgment if transaction is

approved by a fully-informed stockholder

vote[13]

.

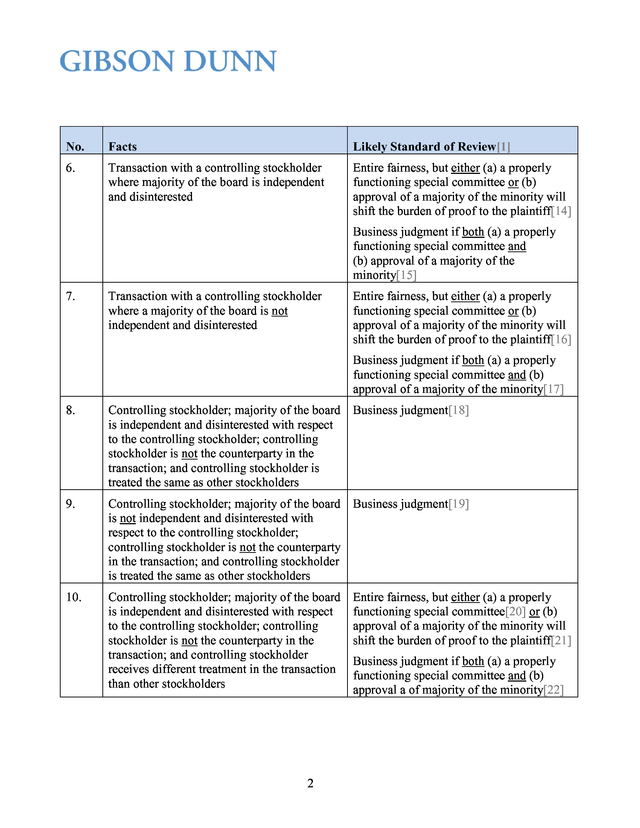

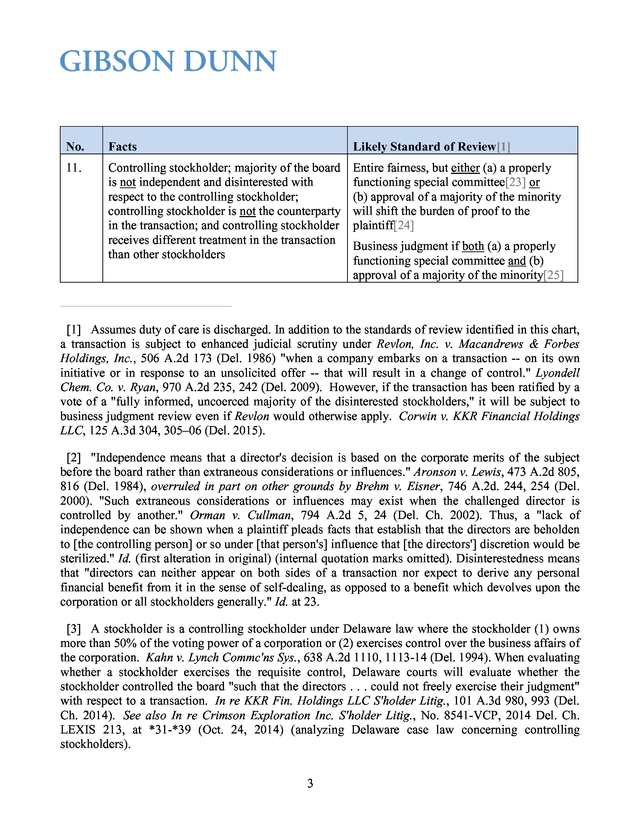

No. Facts Likely Standard of Review[1] 6. Transaction with a controlling stockholder where majority of the board is independent and disinterested Entire fairness, but either (a) a properly functioning special committee or (b) approval of a majority of the minority will shift the burden of proof to the plaintiff[14] Business judgment if both (a) a properly functioning special committee and (b) approval of a majority of the minority[15] 7. Transaction with a controlling stockholder where a majority of the board is not independent and disinterested Entire fairness, but either (a) a properly functioning special committee or (b) approval of a majority of the minority will shift the burden of proof to the plaintiff[16] Business judgment if both (a) a properly functioning special committee and (b) approval of a majority of the minority[17] 8. Controlling stockholder; majority of the board Business judgment[18] is independent and disinterested with respect to the controlling stockholder; controlling stockholder is not the counterparty in the transaction; and controlling stockholder is treated the same as other stockholders 9. Controlling stockholder; majority of the board Business judgment[19] is not independent and disinterested with respect to the controlling stockholder; controlling stockholder is not the counterparty in the transaction; and controlling stockholder is treated the same as other stockholders 10. Controlling stockholder; majority of the board is independent and disinterested with respect to the controlling stockholder; controlling stockholder is not the counterparty in the transaction; and controlling stockholder receives different treatment in the transaction than other stockholders 2 Entire fairness, but either (a) a properly functioning special committee[20] or (b) approval of a majority of the minority will shift the burden of proof to the plaintiff[21] Business judgment if both (a) a properly functioning special committee and (b) approval a of majority of the minority[22] . No. Facts Likely Standard of Review[1] 11. Controlling stockholder; majority of the board is not independent and disinterested with respect to the controlling stockholder; controlling stockholder is not the counterparty in the transaction; and controlling stockholder receives different treatment in the transaction than other stockholders Entire fairness, but either (a) a properly functioning special committee[23] or (b) approval of a majority of the minority will shift the burden of proof to the plaintiff[24] Business judgment if both (a) a properly functioning special committee and (b) approval of a majority of the minority[25] [1] Assumes duty of care is discharged. In addition to the standards of review identified in this chart, a transaction is subject to enhanced judicial scrutiny under Revlon, Inc. v. Macandrews & Forbes Holdings, Inc., 506 A.2d 173 (Del.

1986) "when a company embarks on a transaction -- on its own initiative or in response to an unsolicited offer -- that will result in a change of control." Lyondell Chem. Co. v.

Ryan, 970 A.2d 235, 242 (Del. 2009). However, if the transaction has been ratified by a vote of a "fully informed, uncoerced majority of the disinterested stockholders," it will be subject to business judgment review even if Revlon would otherwise apply.

Corwin v. KKR Financial Holdings LLC, 125 A.3d 304, 305–06 (Del. 2015). [2] "Independence means that a director's decision is based on the corporate merits of the subject before the board rather than extraneous considerations or influences." Aronson v.

Lewis, 473 A.2d 805, 816 (Del. 1984), overruled in part on other grounds by Brehm v. Eisner, 746 A.2d.

244, 254 (Del. 2000). "Such extraneous considerations or influences may exist when the challenged director is controlled by another." Orman v. Cullman, 794 A.2d 5, 24 (Del.

Ch. 2002). Thus, a "lack of independence can be shown when a plaintiff pleads facts that establish that the directors are beholden to [the controlling person] or so under [that person's] influence that [the directors'] discretion would be sterilized." Id.

(first alteration in original) (internal quotation marks omitted). Disinterestedness means that "directors can neither appear on both sides of a transaction nor expect to derive any personal financial benefit from it in the sense of self-dealing, as opposed to a benefit which devolves upon the corporation or all stockholders generally." Id. at 23. [3] A stockholder is a controlling stockholder under Delaware law where the stockholder (1) owns more than 50% of the voting power of a corporation or (2) exercises control over the business affairs of the corporation.

Kahn v. Lynch Commc'ns Sys., 638 A.2d 1110, 1113-14 (Del. 1994).

When evaluating whether a stockholder exercises the requisite control, Delaware courts will evaluate whether the stockholder controlled the board "such that the directors . . .

could not freely exercise their judgment" with respect to a transaction. In re KKR Fin. Holdings LLC S'holder Litig., 101 A.3d 980, 993 (Del. Ch.

2014). See also In re Crimson Exploration Inc. S'holder Litig., No.

8541-VCP, 2014 Del. Ch. LEXIS 213, at *31-*39 (Oct. 24, 2014) (analyzing Delaware case law concerning controlling stockholders). 3 .

[4] See In re Trados Inc. S'holder Litig., 73 A.3d 17, 36 (Del. Ch. 2013) (clarifying that the "business judgment rule" applies to decisions by board members who are "disinterested and independent"). [5] The business judgment rule is generally the applicable standard of review where a majority of the board is disinterested and independent.

See Cinerama, Inc. v. Technicolor, 663 A.2d 1156, 1170 (Del.

1995). Nonetheless, a transaction must be "approved by a majority consisting of the disinterested directors" in order for the business judgment rule to apply. See Aronson v.

Lewis, 473 A.2d at 812, overruled in part on other grounds by Brehm v. Eisner, 746 A.2d. at 254; see also In re Trados Inc. S'holder Litig., 73 A.3d at 44 ("To obtain review under the entire fairness test, the stockholder plaintiff must prove that there were not enough independent and disinterested individuals among the directors making the challenged decision to comprise a board majority.

. . .

To determine whether directors approving the transaction comprised a disinterested and independent board majority, the court conducts a director-by-director analysis."); Chaffin v. GNI Group, Inc., No. 16211-NC, 1999 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 182, at *13-*19 (Sept. 3, 1999) (holding that where a board had three independent and disinterested members and two interested members, and the board approved a merger by a vote of 4-1, with one of the independent and disinterested directors voting against the merger, the merger approval "was one vote short of the required disinterested majority"); Puma v. Marriott, 283 A.2d 693, 693-94, 696 (Del.

Ch. 1971) (rejecting a derivative challenge to a corporate acquisition where the five outside directors on a nine-member board unanimously authorized the acquisition). [6] "A board that is evenly divided between conflicted and non-conflicted members is not considered independent and disinterested." Gentile v. Rossette, No.

20213-VCN, 2010 Del. Ch. LEXIS 123, at *30-*31 n.36 (May 28, 2010).

"[T]he business judgment rule has no application" to a merger transaction that is "not approved by a majority consisting of the disinterested directors," Aronson v. Lewis, 473 A.2d at 812, overruled in part on other grounds by Brehm v. Eisner, 746 A.2d. at 254, and where the "business judgment rule" has been "rebut[ted]" this "lead[s] to the application of the entire fairness standard," In re Crimson Exploration Inc.

S'holder Litig., 2014 Del. Ch. LEXIS 213, at *68. [7] The relevant law is not entirely clear, but the better reasoned view appears to be that a properly functioning special committee brings the business judgment rule to bear.

See In re W. Nat'l S'holder Litig., No. 15927, 2000 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 82, at *86-*88 (May 22, 2000) (explaining that the "[t]he use of an independent special committee, bargaining at arm's length with a controlling shareholder, to shift the burden of proving entire fairness is well noted . .

. . The policy rationale requiring some variant of entire fairness review, to my mind, substantially, if not entirely, abates if the transaction in question involves a large though not controlling shareholder.

In other words, because the absence of a controlling shareholder removes the prospect of retaliation, the business judgment rule should apply to an independent special committee's good faith and fully informed recommendation."); see also In re PNB Holding Co. S'holders Litig., No. 28-N, 2006 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 158, at *50 n.69 (Aug. 18, 2006) (then Vice Chancellor Strine explaining that the business judgment rule would apply if a properly functioning special committee had "negotiated and approved the transaction").

There is, however, some other precedent that could be read to suggest that a properly functioning special committee does no more than shift the burden of the proof to the plaintiff, see In re Tele-Commc'ns., Inc. S'holders Litig., No. 16470, 2005 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 206, at *32-*33 (Dec. 21, 2005), although the better reading 4 .

of this precedent may be that it involved a controlling stockholder, see In re John Q. Hammons Hotels Inc. S'holder Litig., No. 758-CC, 2009 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 174, at *34 (Oct. 2, 2009) (interpreting In re Tele-Commc'ns as having involved a controlling shareholder).

In any event, the Delaware Supreme Court has not definitively resolved the question of which standard of review applies when a special committee approves a transaction and there is no controlling stockholder. [8] See Corwin, 125 A.3d 304 (holding that, in the absence of a controlling stockholder, an uncoerced, informed stockholder vote causes the application of the business judgment standard of review even where enhanced scrutiny would otherwise apply); see also Vice Chancellor J. Travis Laster, The Effect of Stockholder Approval on Enhanced Scrutiny, 40 Wm. Mitchell L.

Rev. 1443 (2014) (providing substantial discussion of the interplay between stockholder approval and the standard of review prior to the decision in Corwin). Note, however, that the failure to disclose all material information to stockholders can prevent a stockholder vote from being fully informed, and would thus prevent the vote from "ratifying" the transaction.

See Chen v. Howard-Anderson, 87 A.3d 648, 669 (Del. Ch.

2014) (noting that, even if defendants had argued that the stockholder vote ratified the challenged transaction, "disclosure deficiencies" would undermine the vote and render the ratification ineffective). [9] See In re Trados Inc. S'holder Litig., 73 A.3d at 45 (holding that entire fairness was the applicable standard of review in scrutinizing a board's approval of a merger where "the plaintiff proved at trial that six of the seven . .

. directors were not disinterested and independent"). In re TeleCommc'ns, Inc., 2005 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 206, at *25-*32 (explaining that an "entire fairness analysis" is required whenever "evidence in the record suggests that a majority of the board of directors were interested in the transaction" and providing several examples). [10] See note 8, supra. [11] See Corwin, 125 A.3d 304. [12] See In re PNB Holding Co., 2006 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 158, at *40-*41, *50 (concluding that all of the members of the board were interested and that entire fairness was the standard of review, recognizing that stockholder approval for the merger was accordingly "the only basis for the defendants to escape entire fairness review," but ultimately concluding that "[b]ecause a majority of the minority did not vote for the Merger, the directors cannot look to our law's cleansing mechanism of ratification to avoid entire fairness review"). [13] See note 12, supra. [14] See Kahn, 638 A.2d at 1117 (the "standard of judicial review in examining the propriety of an interested cash-out merger transaction by a controlling or dominating shareholder is entire fairness. . .

. However, an approval of the transaction by an independent committee of directors or an informed majority of minority shareholders shifts the burden of proof . . .

to the challenging shareholderplaintiff."). 5 . [15] The detailed requirements for the business judgment review to apply to a controllingstockholder transaction are set forth in Kahn v. M&F Worldwide Corp., 88 A.3d 635 (Del. 2014) as follows: "(i) the controller conditions the procession of the transaction on the approval of both a Special Committee and a majority of the minority stockholders; (ii) the Special Committee is independent; (iii) the Special Committee is empowered to freely select its own advisors and to say no definitively; (iv) the Special Committee meets its duty of care in negotiating a fair price; (v) the vote of the minority is informed; and (vi) there is no coercion of the minority." Id. at 645. [16] Kahn, 638 A.2d at 1117. [17] See note 16, supra. [18] See In re Synthes, Inc.

S'holder Litigation, 50 A.3d 1022, 1046 (Del. Ch. 2012) (applying business judgment review despite pled facts that a majority of the board was not independent with respect to the controlling stockholder because the controlling stockholder "received equal treatment in the Merger"). [19] "Entire fairness is not triggered solely because a company has a controlling stockholder.

The controller also must engage in a conflicted transaction." In re Crimson Exploration Inc. S'holder Litig., 2014 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 213, at *39; see also id. at *40-*47 (continuing on to note that a conflicted transaction could arise when (i) a controlling stockholder stands on both sides of a transaction, (ii) a controlling stockholder receives consideration that differs from that received by the other stockholders, or (iii) a controlling stockholder receives a special benefit from the transaction, such as meeting a unique need for liquidity or effectively extinguishing a claim against it); see also In re Synthes, 50 A.3d at 1041. [20] See In re John Q. Hammons Hotels Inc.

S'holder Litig., No. 758-CC, 2011 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 1, at *7 (Jan. 14, 2011) ("[P]laintiffs bear the ultimate burden to show the transaction was unfair given the undisputed evidence that the transaction was approved by an independent and disinterested special committee of directors."). [21] Although we have not identified any Delaware cases explicitly addressing the effect on the standard of review of approval by a majority of the minority stockholders in this factual scenario, it would be reasonable to conclude that the reasoning of Kahn v. Lynch, 638 A.2d 1110, would apply. [22] See In re John Q.

Hammons Hotels Inc. S'holder Litig., 2009 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 174, at *39 (in transaction where controlling stockholder receives different consideration than minority stockholders, "business judgment would be the applicable standard of review if the transaction were (1) recommended by a disinterested and independent special committee, and (2) approved by stockholders in a non-waivable vote of the majority of all the minority stockholders"). [23] In re Tele-Commc'ns, Inc., 2005 Del. Ch. LEXIS 206, at *32–*33 (explaining that because of the directors' interested status "[t]he initial burden of proof rests upon the director defendants to demonstrate .

. . fairness," but further explaining that "[r]atification by a majority of disinterested directors, generally serving on a special committee, can have the effect of shifting the burden onto the 6 .

plaintiff shareholders to demonstrate that the transaction in question was unfair. In order to shift the burden, defendants must establish that the special committee was truly independent, fully informed, and had the freedom to negotiate at arm's length."). [24] See note 22, supra. [25] See note 23, supra. Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher's lawyers are available to assist with any questions you may have regarding these issues. For further information, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work or the authors of this alert: Robert B. Little - Dallas (214-698-3260, rlittle@gibsondunn.com) Chris Babcock - Dallas (214-698-3138, cbabcock@gibsondunn.com) Michael Q.

Cannon - Dallas (214-698-3232, mcannon@gibsondunn.com) Please also feel free to contact any of the following practice group leaders: Mergers and Acquisitions Group: Barbara L. Becker - New York (212-351-4062, bbecker@gibsondunn.com) Jeffrey A. Chapman - Dallas (214-698-3120, jchapman@gibsondunn.com) Stephen I.

Glover - Washington, D.C. (202-955-8593, siglover@gibsondunn.com) Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance Group: James J. Moloney - Orange County, CA (+1 949-451-4343, jmoloney@gibsondunn.com) Elizabeth Ising - Washington, D.C.

(+1 202-955-8287, eising@gibsondunn.com) © 2016 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice. 7 .

No. Facts Likely Standard of Review[1] 6. Transaction with a controlling stockholder where majority of the board is independent and disinterested Entire fairness, but either (a) a properly functioning special committee or (b) approval of a majority of the minority will shift the burden of proof to the plaintiff[14] Business judgment if both (a) a properly functioning special committee and (b) approval of a majority of the minority[15] 7. Transaction with a controlling stockholder where a majority of the board is not independent and disinterested Entire fairness, but either (a) a properly functioning special committee or (b) approval of a majority of the minority will shift the burden of proof to the plaintiff[16] Business judgment if both (a) a properly functioning special committee and (b) approval of a majority of the minority[17] 8. Controlling stockholder; majority of the board Business judgment[18] is independent and disinterested with respect to the controlling stockholder; controlling stockholder is not the counterparty in the transaction; and controlling stockholder is treated the same as other stockholders 9. Controlling stockholder; majority of the board Business judgment[19] is not independent and disinterested with respect to the controlling stockholder; controlling stockholder is not the counterparty in the transaction; and controlling stockholder is treated the same as other stockholders 10. Controlling stockholder; majority of the board is independent and disinterested with respect to the controlling stockholder; controlling stockholder is not the counterparty in the transaction; and controlling stockholder receives different treatment in the transaction than other stockholders 2 Entire fairness, but either (a) a properly functioning special committee[20] or (b) approval of a majority of the minority will shift the burden of proof to the plaintiff[21] Business judgment if both (a) a properly functioning special committee and (b) approval a of majority of the minority[22] . No. Facts Likely Standard of Review[1] 11. Controlling stockholder; majority of the board is not independent and disinterested with respect to the controlling stockholder; controlling stockholder is not the counterparty in the transaction; and controlling stockholder receives different treatment in the transaction than other stockholders Entire fairness, but either (a) a properly functioning special committee[23] or (b) approval of a majority of the minority will shift the burden of proof to the plaintiff[24] Business judgment if both (a) a properly functioning special committee and (b) approval of a majority of the minority[25] [1] Assumes duty of care is discharged. In addition to the standards of review identified in this chart, a transaction is subject to enhanced judicial scrutiny under Revlon, Inc. v. Macandrews & Forbes Holdings, Inc., 506 A.2d 173 (Del.

1986) "when a company embarks on a transaction -- on its own initiative or in response to an unsolicited offer -- that will result in a change of control." Lyondell Chem. Co. v.

Ryan, 970 A.2d 235, 242 (Del. 2009). However, if the transaction has been ratified by a vote of a "fully informed, uncoerced majority of the disinterested stockholders," it will be subject to business judgment review even if Revlon would otherwise apply.

Corwin v. KKR Financial Holdings LLC, 125 A.3d 304, 305–06 (Del. 2015). [2] "Independence means that a director's decision is based on the corporate merits of the subject before the board rather than extraneous considerations or influences." Aronson v.

Lewis, 473 A.2d 805, 816 (Del. 1984), overruled in part on other grounds by Brehm v. Eisner, 746 A.2d.

244, 254 (Del. 2000). "Such extraneous considerations or influences may exist when the challenged director is controlled by another." Orman v. Cullman, 794 A.2d 5, 24 (Del.

Ch. 2002). Thus, a "lack of independence can be shown when a plaintiff pleads facts that establish that the directors are beholden to [the controlling person] or so under [that person's] influence that [the directors'] discretion would be sterilized." Id.

(first alteration in original) (internal quotation marks omitted). Disinterestedness means that "directors can neither appear on both sides of a transaction nor expect to derive any personal financial benefit from it in the sense of self-dealing, as opposed to a benefit which devolves upon the corporation or all stockholders generally." Id. at 23. [3] A stockholder is a controlling stockholder under Delaware law where the stockholder (1) owns more than 50% of the voting power of a corporation or (2) exercises control over the business affairs of the corporation.

Kahn v. Lynch Commc'ns Sys., 638 A.2d 1110, 1113-14 (Del. 1994).

When evaluating whether a stockholder exercises the requisite control, Delaware courts will evaluate whether the stockholder controlled the board "such that the directors . . .

could not freely exercise their judgment" with respect to a transaction. In re KKR Fin. Holdings LLC S'holder Litig., 101 A.3d 980, 993 (Del. Ch.

2014). See also In re Crimson Exploration Inc. S'holder Litig., No.

8541-VCP, 2014 Del. Ch. LEXIS 213, at *31-*39 (Oct. 24, 2014) (analyzing Delaware case law concerning controlling stockholders). 3 .

[4] See In re Trados Inc. S'holder Litig., 73 A.3d 17, 36 (Del. Ch. 2013) (clarifying that the "business judgment rule" applies to decisions by board members who are "disinterested and independent"). [5] The business judgment rule is generally the applicable standard of review where a majority of the board is disinterested and independent.

See Cinerama, Inc. v. Technicolor, 663 A.2d 1156, 1170 (Del.

1995). Nonetheless, a transaction must be "approved by a majority consisting of the disinterested directors" in order for the business judgment rule to apply. See Aronson v.

Lewis, 473 A.2d at 812, overruled in part on other grounds by Brehm v. Eisner, 746 A.2d. at 254; see also In re Trados Inc. S'holder Litig., 73 A.3d at 44 ("To obtain review under the entire fairness test, the stockholder plaintiff must prove that there were not enough independent and disinterested individuals among the directors making the challenged decision to comprise a board majority.

. . .

To determine whether directors approving the transaction comprised a disinterested and independent board majority, the court conducts a director-by-director analysis."); Chaffin v. GNI Group, Inc., No. 16211-NC, 1999 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 182, at *13-*19 (Sept. 3, 1999) (holding that where a board had three independent and disinterested members and two interested members, and the board approved a merger by a vote of 4-1, with one of the independent and disinterested directors voting against the merger, the merger approval "was one vote short of the required disinterested majority"); Puma v. Marriott, 283 A.2d 693, 693-94, 696 (Del.

Ch. 1971) (rejecting a derivative challenge to a corporate acquisition where the five outside directors on a nine-member board unanimously authorized the acquisition). [6] "A board that is evenly divided between conflicted and non-conflicted members is not considered independent and disinterested." Gentile v. Rossette, No.

20213-VCN, 2010 Del. Ch. LEXIS 123, at *30-*31 n.36 (May 28, 2010).

"[T]he business judgment rule has no application" to a merger transaction that is "not approved by a majority consisting of the disinterested directors," Aronson v. Lewis, 473 A.2d at 812, overruled in part on other grounds by Brehm v. Eisner, 746 A.2d. at 254, and where the "business judgment rule" has been "rebut[ted]" this "lead[s] to the application of the entire fairness standard," In re Crimson Exploration Inc.

S'holder Litig., 2014 Del. Ch. LEXIS 213, at *68. [7] The relevant law is not entirely clear, but the better reasoned view appears to be that a properly functioning special committee brings the business judgment rule to bear.

See In re W. Nat'l S'holder Litig., No. 15927, 2000 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 82, at *86-*88 (May 22, 2000) (explaining that the "[t]he use of an independent special committee, bargaining at arm's length with a controlling shareholder, to shift the burden of proving entire fairness is well noted . .

. . The policy rationale requiring some variant of entire fairness review, to my mind, substantially, if not entirely, abates if the transaction in question involves a large though not controlling shareholder.

In other words, because the absence of a controlling shareholder removes the prospect of retaliation, the business judgment rule should apply to an independent special committee's good faith and fully informed recommendation."); see also In re PNB Holding Co. S'holders Litig., No. 28-N, 2006 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 158, at *50 n.69 (Aug. 18, 2006) (then Vice Chancellor Strine explaining that the business judgment rule would apply if a properly functioning special committee had "negotiated and approved the transaction").

There is, however, some other precedent that could be read to suggest that a properly functioning special committee does no more than shift the burden of the proof to the plaintiff, see In re Tele-Commc'ns., Inc. S'holders Litig., No. 16470, 2005 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 206, at *32-*33 (Dec. 21, 2005), although the better reading 4 .

of this precedent may be that it involved a controlling stockholder, see In re John Q. Hammons Hotels Inc. S'holder Litig., No. 758-CC, 2009 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 174, at *34 (Oct. 2, 2009) (interpreting In re Tele-Commc'ns as having involved a controlling shareholder).

In any event, the Delaware Supreme Court has not definitively resolved the question of which standard of review applies when a special committee approves a transaction and there is no controlling stockholder. [8] See Corwin, 125 A.3d 304 (holding that, in the absence of a controlling stockholder, an uncoerced, informed stockholder vote causes the application of the business judgment standard of review even where enhanced scrutiny would otherwise apply); see also Vice Chancellor J. Travis Laster, The Effect of Stockholder Approval on Enhanced Scrutiny, 40 Wm. Mitchell L.

Rev. 1443 (2014) (providing substantial discussion of the interplay between stockholder approval and the standard of review prior to the decision in Corwin). Note, however, that the failure to disclose all material information to stockholders can prevent a stockholder vote from being fully informed, and would thus prevent the vote from "ratifying" the transaction.

See Chen v. Howard-Anderson, 87 A.3d 648, 669 (Del. Ch.

2014) (noting that, even if defendants had argued that the stockholder vote ratified the challenged transaction, "disclosure deficiencies" would undermine the vote and render the ratification ineffective). [9] See In re Trados Inc. S'holder Litig., 73 A.3d at 45 (holding that entire fairness was the applicable standard of review in scrutinizing a board's approval of a merger where "the plaintiff proved at trial that six of the seven . .

. directors were not disinterested and independent"). In re TeleCommc'ns, Inc., 2005 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 206, at *25-*32 (explaining that an "entire fairness analysis" is required whenever "evidence in the record suggests that a majority of the board of directors were interested in the transaction" and providing several examples). [10] See note 8, supra. [11] See Corwin, 125 A.3d 304. [12] See In re PNB Holding Co., 2006 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 158, at *40-*41, *50 (concluding that all of the members of the board were interested and that entire fairness was the standard of review, recognizing that stockholder approval for the merger was accordingly "the only basis for the defendants to escape entire fairness review," but ultimately concluding that "[b]ecause a majority of the minority did not vote for the Merger, the directors cannot look to our law's cleansing mechanism of ratification to avoid entire fairness review"). [13] See note 12, supra. [14] See Kahn, 638 A.2d at 1117 (the "standard of judicial review in examining the propriety of an interested cash-out merger transaction by a controlling or dominating shareholder is entire fairness. . .

. However, an approval of the transaction by an independent committee of directors or an informed majority of minority shareholders shifts the burden of proof . . .

to the challenging shareholderplaintiff."). 5 . [15] The detailed requirements for the business judgment review to apply to a controllingstockholder transaction are set forth in Kahn v. M&F Worldwide Corp., 88 A.3d 635 (Del. 2014) as follows: "(i) the controller conditions the procession of the transaction on the approval of both a Special Committee and a majority of the minority stockholders; (ii) the Special Committee is independent; (iii) the Special Committee is empowered to freely select its own advisors and to say no definitively; (iv) the Special Committee meets its duty of care in negotiating a fair price; (v) the vote of the minority is informed; and (vi) there is no coercion of the minority." Id. at 645. [16] Kahn, 638 A.2d at 1117. [17] See note 16, supra. [18] See In re Synthes, Inc.

S'holder Litigation, 50 A.3d 1022, 1046 (Del. Ch. 2012) (applying business judgment review despite pled facts that a majority of the board was not independent with respect to the controlling stockholder because the controlling stockholder "received equal treatment in the Merger"). [19] "Entire fairness is not triggered solely because a company has a controlling stockholder.

The controller also must engage in a conflicted transaction." In re Crimson Exploration Inc. S'holder Litig., 2014 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 213, at *39; see also id. at *40-*47 (continuing on to note that a conflicted transaction could arise when (i) a controlling stockholder stands on both sides of a transaction, (ii) a controlling stockholder receives consideration that differs from that received by the other stockholders, or (iii) a controlling stockholder receives a special benefit from the transaction, such as meeting a unique need for liquidity or effectively extinguishing a claim against it); see also In re Synthes, 50 A.3d at 1041. [20] See In re John Q. Hammons Hotels Inc.

S'holder Litig., No. 758-CC, 2011 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 1, at *7 (Jan. 14, 2011) ("[P]laintiffs bear the ultimate burden to show the transaction was unfair given the undisputed evidence that the transaction was approved by an independent and disinterested special committee of directors."). [21] Although we have not identified any Delaware cases explicitly addressing the effect on the standard of review of approval by a majority of the minority stockholders in this factual scenario, it would be reasonable to conclude that the reasoning of Kahn v. Lynch, 638 A.2d 1110, would apply. [22] See In re John Q.

Hammons Hotels Inc. S'holder Litig., 2009 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 174, at *39 (in transaction where controlling stockholder receives different consideration than minority stockholders, "business judgment would be the applicable standard of review if the transaction were (1) recommended by a disinterested and independent special committee, and (2) approved by stockholders in a non-waivable vote of the majority of all the minority stockholders"). [23] In re Tele-Commc'ns, Inc., 2005 Del. Ch. LEXIS 206, at *32–*33 (explaining that because of the directors' interested status "[t]he initial burden of proof rests upon the director defendants to demonstrate .

. . fairness," but further explaining that "[r]atification by a majority of disinterested directors, generally serving on a special committee, can have the effect of shifting the burden onto the 6 .

plaintiff shareholders to demonstrate that the transaction in question was unfair. In order to shift the burden, defendants must establish that the special committee was truly independent, fully informed, and had the freedom to negotiate at arm's length."). [24] See note 22, supra. [25] See note 23, supra. Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher's lawyers are available to assist with any questions you may have regarding these issues. For further information, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work or the authors of this alert: Robert B. Little - Dallas (214-698-3260, rlittle@gibsondunn.com) Chris Babcock - Dallas (214-698-3138, cbabcock@gibsondunn.com) Michael Q.

Cannon - Dallas (214-698-3232, mcannon@gibsondunn.com) Please also feel free to contact any of the following practice group leaders: Mergers and Acquisitions Group: Barbara L. Becker - New York (212-351-4062, bbecker@gibsondunn.com) Jeffrey A. Chapman - Dallas (214-698-3120, jchapman@gibsondunn.com) Stephen I.

Glover - Washington, D.C. (202-955-8593, siglover@gibsondunn.com) Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance Group: James J. Moloney - Orange County, CA (+1 949-451-4343, jmoloney@gibsondunn.com) Elizabeth Ising - Washington, D.C.

(+1 202-955-8287, eising@gibsondunn.com) © 2016 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice. 7 .