Description

Global Challenge Insight Report

The Future of Jobs

Employment, Skills and

Workforce Strategy for the

Fourth Industrial Revolution

January 2016

.

. Global Challenge Insight Report

The Future of Jobs

Employment, Skills and

Workforce Strategy for the

Fourth Industrial Revolution

January 2016

. TERMS OF USE AND DISCLAIMER

The Future of Jobs Report (herein: “Report”) presents information

and data that were compiled and/or collected by the World

Economic Forum (all information and data referred herein as

“Data”). Data in this Report is subject to change without notice.

The terms country and nation as used in this report do not in

all cases refer to a territorial entity that is a state as understood

by international law and practice. The term covers well-defined,

geographically self-contained economic areas that may not be

states but for which statistical data are maintained on a separate

and independent basis.

Although the World Economic Forum takes every reasonable

step to ensure that the Data thus compiled and/or collected is

accurately reflected in this Report, the World Economic Forum,

its agents, officers, and employees: (i) provide the Data “as is,

as available” and without warranty of any kind, either express or

implied, including, without limitation, warranties of merchantability,

fitness for a particular purpose and non-infringement; (ii) make

no representations, express or implied, as to the accuracy of the

Data contained in this Report or its suitability for any particular

purpose; (iii) accept no liability for any use of the said Data or

reliance placed on it, in particular, for any interpretation, decisions,

or actions based on the Data in this Report.

Other parties may have ownership interests in some of the Data

contained in this Report. The World Economic Forum in no way

represents or warrants that it owns or controls all rights in all Data,

and the World Economic Forum will not be liable to users for any

claims brought against users by third parties in connection with

their use of any Data.

The World Economic Forum, its agents, officers, and employees

do not endorse or in any respect warrant any third-party products

or services by virtue of any Data, material, or content referred to

or included in this Report.

Users shall not infringe upon the integrity of the Data and in

particular shall refrain from any act of alteration of the Data that

intentionally affects its nature or accuracy.

If the Data is materially transformed by the user, this must be stated explicitly along with the required source citation. For Data compiled by parties other than the World Economic Forum, users must refer to these parties’ terms of use, in particular concerning the attribution, distribution, and reproduction of the Data. When Data for which the World Economic Forum is the source (herein “World Economic Forum”) is distributed or reproduced, it must appear accurately and be attributed to the World Economic Forum. This source attribution requirement is attached to any use of Data, whether obtained directly from the World Economic Forum or from a user. Users who make World Economic Forum Data available to other users through any type of distribution or download environment agree to make reasonable efforts to communicate and promote compliance by their end users with these terms. Users who intend to sell World Economic Forum Data as part of a database or as a standalone product must first obtain the permission from the World Economic Forum (humancapital@weforum.org). ©2016 World Economic Forum All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system. REF 010116 . Contents v Preface 1 PART 1: PREPARING FOR THE WORKFORCE OF THE FOURTH INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION 3 Chapter 1: The Future of Jobs and Skills 3 Introduction 5 Drivers of Change 10 Employment Trends 19 Skills Stability 26 Future Workforce Strategy 33 34 36 37 39 40 Chapter 2: The Industry Gender Gap The Business Case for Change Gaps in the Female Talent Pipeline Barriers to Change Women and Work in the Fourth Industrial Revolution Approaches to Leveraging Female Talent 43 Endnotes 45 References and Further Reading 49 Appendix A: Report Methodology 57 Appendix B: Industry and Regional Classifications 59 PART 2: INDUSTRY, REGIONAL AND GENDER GAP PROFILES 61 69 71 91 123 User’s Guide: How to Read the Industry, Regional and Gender Gap Profiles List of Industry, Regional and Gender Gap Profiles Industry Profiles Country and Regional Profiles Industry Gender Gap Profiles 143 Acknowledgements 145 Contributors 147 Global Challenge Partners The Future of Jobs Report | iii . iv | The Future of Jobs Report . Preface KLAUS SCHWAB Founder and Executive Chairman RICHARD SAMANS Member of the Managing Board Today, we are at the beginning of a Fourth Industrial Revolution. Developments in genetics, artificial intelligence, robotics, nanotechnology, 3D printing and biotechnology, to name just a few, are all building on and amplifying one another. This will lay the foundation for a revolution more comprehensive and all-encompassing than anything we have ever seen. Smart systems—homes, factories, farms, grids or cities—will help tackle problems ranging from supply chain management to climate change.

The rise of the sharing economy will allow people to monetize everything from their empty house to their car. While the impending change holds great promise, the patterns of consumption, production and employment created by it also pose major challenges requiring proactive adaptation by corporations, governments and individuals. Concurrent to the technological revolution are a set of broader socio-economic, geopolitical and demographic drivers of change, each interacting in multiple directions and intensifying one another. As entire industries adjust, most occupations are undergoing a fundamental transformation. While some jobs are threatened by redundancy and others grow rapidly, existing jobs are also going through a change in the skill sets required to do them. The debate on these transformations is often polarized between those who foresee limitless new opportunities and those that foresee massive dislocation of jobs.

In fact, the reality is highly specific to the industry, region and occupation in question as well as the ability of various stakeholders to manage change. The Future of Jobs Report is a first step in becoming specific about the changes at hand. It taps into the knowledge of those who are best placed to observe the dynamics of workforces—Chief Human Resources and Strategy Officers—by asking them what the current shifts mean, specifically for employment, skills and recruitment across industries and geographies. In particular, we have introduced a new measure—skills stability—to quantify the degree of skills disruption within an occupation, a job family or an entire industry.

We have also been able to provide an outlook on the gender dynamics of the changes underway, a key element in understanding how the benefits and burdens of the Fourth Industrial Revolution will be distributed. Overall, there is a modestly positive outlook for employment across most industries, with jobs growth expected in several sectors. However, it is also clear that this need for more talent in certain job categories is accompanied by high skills instability across all job categories. Combined together, net job growth and skills instability result in most businesses currently facing major recruitment challenges and talent shortages, a pattern already evident in the results and set to get worse over the next five years. The question, then, is how business, government and individuals will react to these developments.

To prevent a worst-case scenario—technological change accompanied by talent shortages, mass unemployment and growing inequality—reskilling and upskilling of today’s workers will be critical. While much has been said about the need for reform in basic education, it is simply not possible to weather the current technological revolution by waiting for the next generation’s workforce to become better prepared. Instead it is critical that businesses take an active role in supporting their current workforces through re-training, that individuals take a proactive approach to their own lifelong learning and that governments create the enabling environment, rapidly and creatively, to assist these efforts. In particular, business collaboration within industries to create larger pools of skilled talent will become indispensable, as will multi-sector skilling partnerships that leverage the very same collaborative models that underpin many of the technology-driven business changes underway today. Additionally, better data and planning metrics, such as those in this Report, are critical in helping to anticipate and proactively manage the current transition in labour markets. We are grateful for the leadership of Jeffrey Joerres, Executive Chairman Emeritus, ManpowerGroup and Chair of the Global Agenda Council on the Future of Jobs; Jamie McAuliffe, President and CEO, Education for Employment and Vice-Chair of the Global Agenda Council on the Future of Jobs; J.

Frank Brown, Managing Director and Chief Operating Officer, General Atlantic LLC and Chair of the Global Agenda Council on Gender Parity and Mara Swan, Executive Vice-President, Global Strategy and Talent, ManpowerGroup and Vice-Chair of the Global Agenda Council on Gender Parity. We would also like to express our appreciation to Till Leopold, Project Lead, Employment, Skills and Human Capital Initiative; Vesselina Ratcheva, Data Analyst, Employment and Gender Initiatives; and Saadia Zahidi, Head of Employment and Gender Initiatives, for their dedication to this Report. We would like to thank Yasmina Bekhouche, Kristin Keveloh, Paulina Padilla Ugarte, Valerie Peyre, Pearl Samandari and Susan Wilkinson for their support of this project at the World Economic Forum. Finally, we welcome the untiring commitment of the Partners of the Global Challenge Initiative on Employment, Skills and Human Capital and the Global Challenge Initiative on The Future of Jobs Report | v . Gender Parity, who have each been instrumental in shaping this combined Report of the two Global Challenge Initiatives. The current technological revolution need not become a race between humans and machines but rather an opportunity for work to truly become a channel through which people recognize their full potential. To ensure that we achieve this vision, we must become more specific and much faster in understanding the changes underway and cognizant of our collective responsibility to lead our businesses and communities through this transformative moment. vi | The Future of Jobs Report . Part 1 Preparing for the Workforce of the Fourth Industrial Revolution . . Chapter 1: The Future of Jobs and Skills INTRODUCTION Disruptive changes to business models will have a profound impact on the employment landscape over the coming years. Many of the major drivers of transformation currently affecting global industries are expected to have a significant impact on jobs, ranging from significant job creation to job displacement, and from heightened labour productivity to widening skills gaps. In many industries and countries, the most in-demand occupations or specialties did not exist 10 or even five years ago, and the pace of change is set to accelerate. By one popular estimate, 65% of children entering primary school today will ultimately end up working in completely new job types that don’t yet exist.1 In such a rapidly evolving employment landscape, the ability to anticipate and prepare for future skills requirements, job content and the aggregate effect on employment is increasingly critical for businesses, governments and individuals in order to fully seize the opportunities presented by these trends—and to mitigate undesirable outcomes. Past waves of technological advancement and demographic change have led to increased prosperity, productivity and job creation.

This does not mean, however, that these transitions were free of risk or difficulty. Anticipating and preparing for the current transition is therefore critical. As a core component of the World Economic Forum’s Global Challenge Initiative on Employment, Skills and Human Capital, the Future of Jobs project aims to bring specificity to the upcoming disruptions to the employment and skills landscape in industries and regions—and to stimulate deeper thinking about how business and governments can manage this change.

The industry analysis presented in this Report will form the basis of dialogue with industry leaders to address industry-specific talent challenges, while the country and regional analysis presented in this Report will be integrated into national and regional public-private collaborations to promote employment and skills. The Report’s research framework has been shaped and developed in collaboration with the Global Agenda Council on the Future of Jobs and the Global Agenda Council on Gender Parity, including leading experts from academia, international organizations, professional service firms and the heads of human resources of major organizations. The employer survey at the heart of this Report was conducted through the World Economic Forum’s membership and with the particular support of three Employment, Skills and Human Capital Global Challenge Partners: Adecco Group, ManpowerGroup and Mercer. This Report seeks to understand the current and future impact of key disruptions on employment levels, skill sets and recruitment patterns in different industries and countries. It does so by asking the Chief Human Resources Officers (CHROs) of today’s largest employers to imagine how jobs in their industry will change up to the year 2020— far enough into the future for many of today’s expected trends and disruptions to have begun taking hold, yet close enough to consider adaptive action today, rather than merely speculate on future risks and opportunities. While only a minority of the world’s global workforce of more than three billion people is directly employed by large and emerging multinational employers, these companies often act as anchors for smaller firms and local entrepreneurship ecosystems.

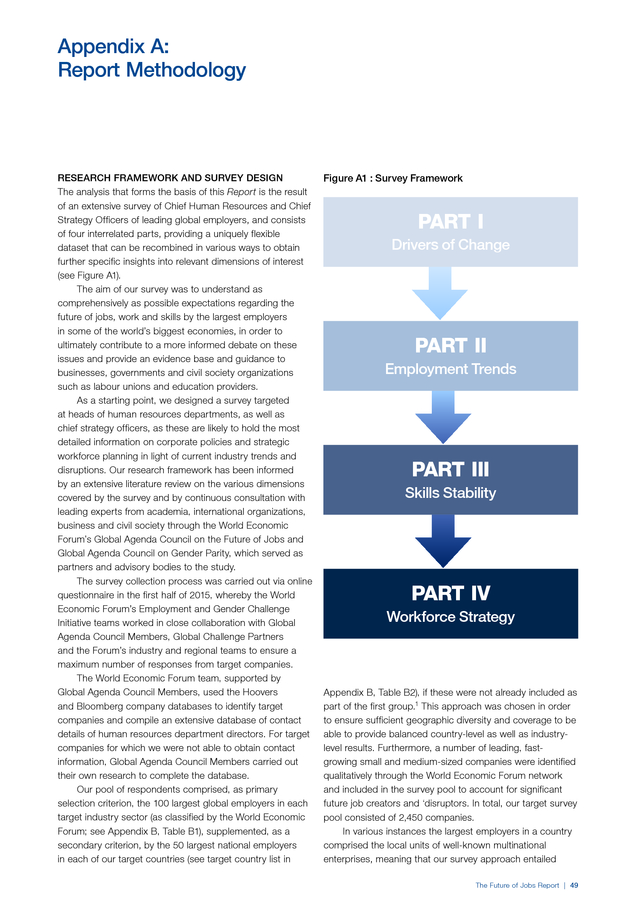

Therefore, in addition to their own significant share of employment, workforce-planning decisions by these firms have the potential to transform local labour markets through indirect employment and by setting the pace for changing skills and occupational requirements. This Report aims to serve as a call to action. While the implications of current disruptions to business models for jobs are far-reaching, even daunting, rapid adjustment to the new reality and its opportunities is possible, provided there is concerted effort by all stakeholders. By evaluating the future labour market from the perspective of some of the world’s largest employers we hope to improve the current stock of knowledge around anticipated skills needs, recruitment patterns and occupational requirements. Furthermore, it is our hope that this knowledge can incentivize and enhance partnerships between governments, educators, training providers, workers and employers in order to better manage the transformative impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution on employment, skills and education. Survey and Research Design The dataset that forms the basis of this Report is the result of an extensive survey of CHROs and other senior talent and strategy executives of leading global employers, representing more than 13 million employees across 9 broad industry sectors in 15 major developed and emerging economies and regional economic areas.

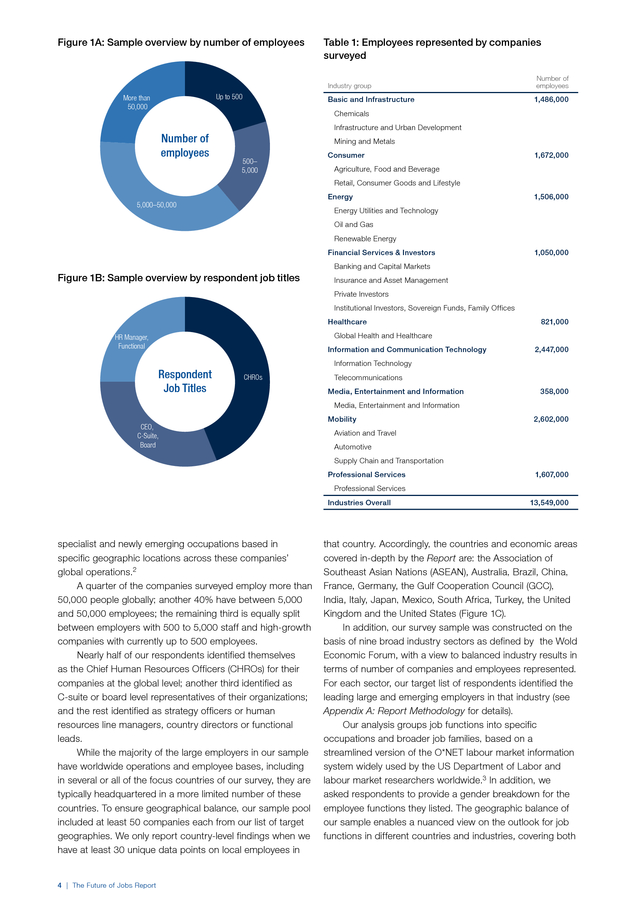

Our target pool of respondents comprised, as the primary selection criterion, the 100 largest global employers in each of our target industry sectors (as classified by the World Economic Forum; see Appendix B, Table B1). A total of 371 individual companies from these industries and regions responded to the survey over the first half of 2015, providing us with 1,346 detailed occupation-level data points on mass employment, The Future of Jobs Report | 3 . Figure 1A: Sample overview by number of employees Table 1: Employees represented by companies surveyed Industry group Basic and Infrastructure Up to 500 More than 50,000 Number of employees 1,486,000 Chemicals Number of employees Infrastructure and Urban Development Mining and Metals 500– 5,000 Consumer 1,672,000 Agriculture, Food and Beverage Retail, Consumer Goods and Lifestyle Energy 5,000–50,000 1,506,000 Energy Utilities and Technology Oil and Gas Renewable Energy Financial Services & Investors 1,050,000 Banking and Capital Markets Figure 1B: Sample overview by respondent job titles Insurance and Asset Management Private Investors Institutional Investors, Sovereign Funds, Family Offices Healthcare 821,000 Global Health and Healthcare HR Manager, Functional Information and Communication Technology Respondent Job Titles 2,447,000 Information Technology CHROs Telecommunications Media, Entertainment and Information 358,000 Media, Entertainment and Information CEO, C-Suite, Board Mobility 2,602,000 Aviation and Travel Automotive Supply Chain and Transportation Professional Services 1,607,000 Professional Services Industries Overall specialist and newly emerging occupations based in specific geographic locations across these companies’ global operations.2 A quarter of the companies surveyed employ more than 50,000 people globally; another 40% have between 5,000 and 50,000 employees; the remaining third is equally split between employers with 500 to 5,000 staff and high-growth companies with currently up to 500 employees. Nearly half of our respondents identified themselves as the Chief Human Resources Officers (CHROs) for their companies at the global level; another third identified as C-suite or board level representatives of their organizations; and the rest identified as strategy officers or human resources line managers, country directors or functional leads. While the majority of the large employers in our sample have worldwide operations and employee bases, including in several or all of the focus countries of our survey, they are typically headquartered in a more limited number of these countries. To ensure geographical balance, our sample pool included at least 50 companies each from our list of target geographies. We only report country-level findings when we have at least 30 unique data points on local employees in 4 | The Future of Jobs Report 13,549,000 that country. Accordingly, the countries and economic areas covered in-depth by the Report are: the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Australia, Brazil, China, France, Germany, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States (Figure 1C). In addition, our survey sample was constructed on the basis of nine broad industry sectors as defined by the Wold Economic Forum, with a view to balanced industry results in terms of number of companies and employees represented. For each sector, our target list of respondents identified the leading large and emerging employers in that industry (see Appendix A: Report Methodology for details). Our analysis groups job functions into specific occupations and broader job families, based on a streamlined version of the O*NET labour market information system widely used by the US Department of Labor and labour market researchers worldwide.3 In addition, we asked respondents to provide a gender breakdown for the employee functions they listed.

The geographic balance of our sample enables a nuanced view on the outlook for job functions in different countries and industries, covering both . Figure 1C: Sample overview by geographic coverage white-collar and blue-collar workers, and both high-income and low-income countries. In the current era of global value chains, many companies are locating different job functions and categories in different geographic locations to take advantage of the specific strengths of particular local labour markets. In addition to asking respondents to provide details on the geographical spread of their workforce, we asked them to distinguish between mass employment jobs (i.e. job functions that are significant to the company’s operations in terms of the absolute number of employees since they form the bulk of its workforce) and specialist jobs (i.e. job categories, such as design and R&D, that are significant to the company’s operations—not necessarily in terms of the absolute number of employees but because they provide specialist skills crucial to its value proposition).

Following this task approach to the global labour market, we found that— depending on the nature of their business—our respondents often locate these functions in different geographic locations.4 Demographic, socio-economic and—increasingly— technological trends and disruptions to the business and operating models of global companies have the potential to rapidly change the dynamics of the global employment landscape. In addition to the outlook for existing roles, we asked respondents to tell us about wholly new occupations and fields of specialization they expect to emerge in their industries as well as those they foresee to be made obsolete over the coming years until 2020. Structure of the Report This Report consists of two parts. Part I explores the future of jobs and the pace of change to the global employment landscape up until the year 2020, as anticipated by the CHROs of some of the world’s largest employers.

It touches, first, on the expected trends, disruptions and drivers of change transforming business models in every industry, with far-reaching implications for skills, jobs and the nature of work. It then reviews the expected effects on employment levels and skills profiles in different job families, industries and geographies. It discusses consequences of these changes for the adequacy of existing talent and workforce strategies.

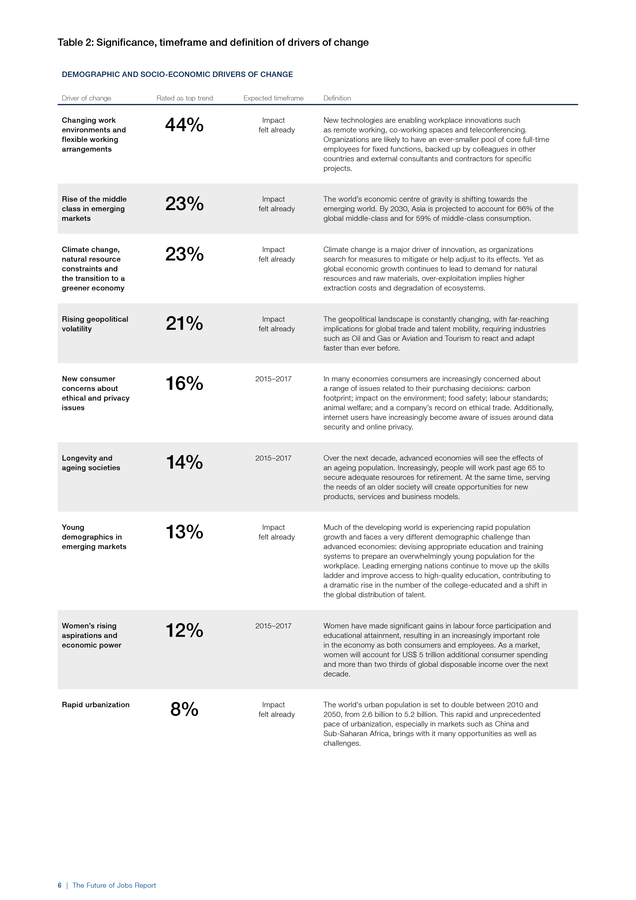

Finally, in a dedicated chapter, it explores the implications of today’s transformations on the future of women’s workforce participation. Part II of the Report presents our findings through an industry, regional and industry gender gap lens—highlighting key industry-by-industry and region-specific trends—and provides a wealth of industry-specific and country-specific practical information to senior decision-makers and experts through dedicated Industry Profiles, Country and Regional Profiles and Industry Gender Gap Profiles. Finally, a detailed Methodological Appendix provides further information on our survey design, sample selection criteria and research methodology. DRIVERS OF CHANGE According to many industry observers, we are today on the cusp of a Fourth Industrial Revolution. Developments in previously disjointed fields such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, robotics, nanotechnology, 3D printing and genetics and biotechnology are all building on and The Future of Jobs Report | 5 . Table 2: Significance, timeframe and definition of drivers of change DEMOGRAPHIC AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC DRIVERS OF CHANGE Driver of change Rated as top trend Expected timeframe Definition Changing work environments and flexible working arrangements 44% Impact felt already New technologies are enabling workplace innovations such as remote working, co-working spaces and teleconferencing. Organizations are likely to have an ever-smaller pool of core full-time employees for fixed functions, backed up by colleagues in other countries and external consultants and contractors for specific projects. Rise of the middle class in emerging markets 23% Impact felt already The world’s economic centre of gravity is shifting towards the emerging world. By 2030, Asia is projected to account for 66% of the global middle-class and for 59% of middle-class consumption. Climate change, natural resource constraints and the transition to a greener economy 23% Impact felt already Climate change is a major driver of innovation, as organizations search for measures to mitigate or help adjust to its effects. Yet as global economic growth continues to lead to demand for natural resources and raw materials, over-exploitation implies higher extraction costs and degradation of ecosystems. Rising geopolitical volatility 21% Impact felt already The geopolitical landscape is constantly changing, with far-reaching implications for global trade and talent mobility, requiring industries such as Oil and Gas or Aviation and Tourism to react and adapt faster than ever before. New consumer concerns about ethical and privacy issues 16% 2015–2017 In many economies consumers are increasingly concerned about a range of issues related to their purchasing decisions: carbon footprint; impact on the environment; food safety; labour standards; animal welfare; and a company’s record on ethical trade. Additionally, internet users have increasingly become aware of issues around data security and online privacy. Longevity and ageing societies 14% 2015–2017 Over the next decade, advanced economies will see the effects of an ageing population.

Increasingly, people will work past age 65 to secure adequate resources for retirement. At the same time, serving the needs of an older society will create opportunities for new products, services and business models. Young demographics in emerging markets 13% Women’s rising aspirations and economic power 12% Rapid urbanization 6 | The Future of Jobs Report 8% Impact felt already 2015–2017 Impact felt already Much of the developing world is experiencing rapid population growth and faces a very different demographic challenge than advanced economies: devising appropriate education and training systems to prepare an overwhelmingly young population for the workplace. Leading emerging nations continue to move up the skills ladder and improve access to high-quality education, contributing to a dramatic rise in the number of the college-educated and a shift in the global distribution of talent. Women have made significant gains in labour force participation and educational attainment, resulting in an increasingly important role in the economy as both consumers and employees.

As a market, women will account for US$ 5 trillion additional consumer spending and more than two thirds of global disposable income over the next decade. The world's urban population is set to double between 2010 and 2050, from 2.6 billion to 5.2 billion. This rapid and unprecedented pace of urbanization, especially in markets such as China and Sub-Saharan Africa, brings with it many opportunities as well as challenges. . Table 2: Significance, timeframe and definition of drivers of change (cont’d.) TECHNOLOGICAL DRIVERS OF CHANGE Driver of change Rated as top trend Expected timeframe Mobile internet and cloud technology 34% 2015–2017 The mobile internet has applications across business and the public sector, enabling more efficient delivery of services and opportunities to increase workforce productivity. With cloud technology, applications can be delivered with minimal or no local software or processing power, enabling the rapid spread of internet-based service models. Advances in computing power and Big Data 26% 2015–2017 Realizing the full potential of technological advances will require having in place the systems and capabilities to make sense of the unprecedented flood of data these innovations will generate. New energy supplies and technologies 22% 2015–2017 New energy supplies and technologies, such as renewables and hydraulic fracturing (fracking), are shaking up the global energy landscape and disrupting powerful players at least as much as yesterday’s oil price crises did, with profound and complicated geopolitical and environmental repercussions. The Internet of Things 14% 2015–2017 The use of remote sensors, communications, and processing power in industrial equipment and everyday objects will unleash an enormous amount of data and the opportunity to see patterns and design systems on a scale never before possible. Crowdsourcing, the sharing economy and peer-to-peer platforms 12% Advanced robotics and autonomous transport 9% 2018–2020 Advanced robots with enhanced senses, dexterity, and intelligence can be more practical than human labour in manufacturing, as well as in a growing number of service jobs, such as cleaning and maintenance. Moreover, it is now possible to create cars, trucks, aircraft, and boats that are completely or partly autonomous, which could revolutionize transportation, if regulations allow, as early as 2020. Artificial intelligence and machine learning 7% 2018–2020 Advances in artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural user interfaces (e.g. voice recognition) are making it possible to automate knowledge-worker tasks that have long been regarded as impossible or impractical for machines to perform. Advanced manufacturing and 3D printing 6% 2015–2017 A range of technological advances in manufacturing technology promises a new wave of productivity.

For example, 3D printing (building objects layer-by-layer from a digital master design file) allows on-demand production, which has far-ranging implications for global supply chains and production networks. Advanced materials, biotechnology and genomics 6% 2018–2020 Technological advances in material and life sciences have many innovative industry applications. Recent breakthroughs in genetics could have profound impacts on medicine and agriculture. Similarly, the manufacture of synthetic molecules via bio-process engineering will be critical to pharmaceuticals, plastics and polymers, biofuels, and other new materials and industrial processes. Impact felt already Definition With peer-to-peer platforms, companies and individuals can do things that previously required large-scale organizations.

In some cases the talent and resources that companies can connect to, through activities such as crowdsourcing, may become more important than the in-house resources they own. The Future of Jobs Report | 7 . Figure 2: Drivers of change, industries overall Share of respondents rating driver as top trend, % DEMOGRAPHIC AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC Changing nature of work, flexible work 44% Middle class in emerging markets 23% Climate change, natural resources 23% Geopolitical volatility 21% Consumer ethics, privacy issues 16% Longevity, ageing societies 14% Young demographics in emerging markets 13% Women’s economic power, aspirations 12% Rapid urbanization 8% TECHNOLOGICAL Mobile internet, cloud technology 34% Processing power, Big Data 26% New energy supplies and technologies 22% Internet of Things 14% Sharing economy, crowdsourcing 12% Robotics, autonomous transport 9% Artificial intelligence 7% Adv. manufacturing, 3D printing 6% Adv. materials, biotechnology 6% 0.0 Source: Future of Jobs Survey, World Economic Forum. 0.0 Note: Names of drivers have been abbreviated to ensure legibility. 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 amplifying one another. Smart systems—homes, factories, farms, grids or entire cities—will help tackle problems ranging from supply chain management to climate change. Concurrent to this technological revolution are a set of broader socio-economic, geopolitical and demographic developments, each interacting in multiple directions and intensifying each another. While these impending changes hold great promise for future prosperity and job creation, many of them also pose major challenges requiring proactive adaptation by corporations, governments, societies and individuals.

As whole industries adjust and new ones are born, many occupations will undergo a fundamental transformation. Together, technological, socio-economic, geopolitical and demographic developments and the interactions between them will generate new categories of jobs and occupations while partly or wholly displacing others. They will change the skill sets required in both old and new occupations in most industries and transform how and where people work, leading to new management and regulatory challenges. 8 | The Future of Jobs Report Given the rapid pace of change, business model disruptions are resulting in a near-simultaneous impact on employment and need for new skill sets, requiring an urgent and concerted effort for adjustment. So far, the debate on these transformations has been sharply polarized between those who foresee limitless new opportunities and those that foresee a massive dislocation of jobs. In fact, the reality is likely to be highly specific to the industry, region and occupation in question and the ability of various stakeholders to successfully manage change.

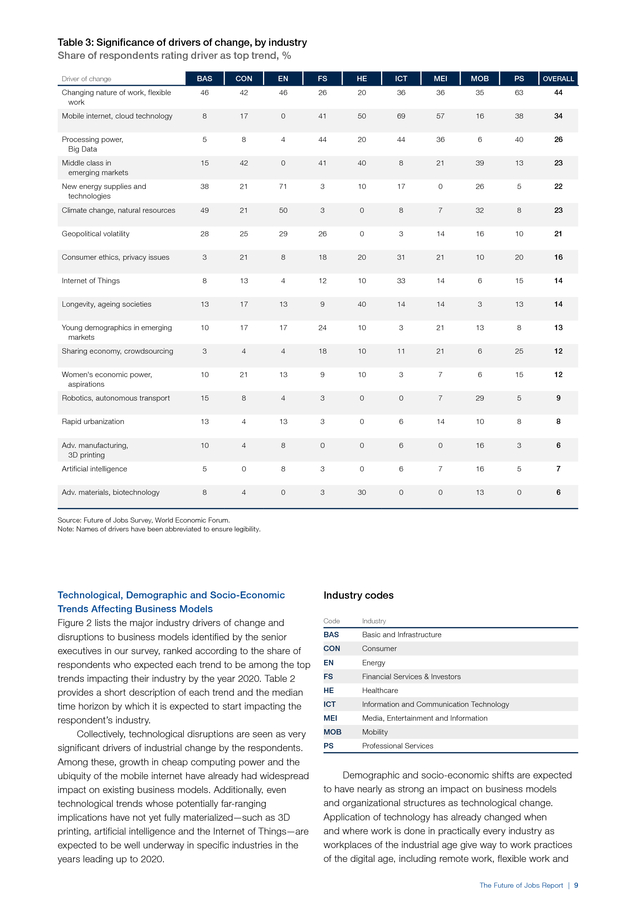

A major goal of this Report is to unpack the relative impact of key drivers of change and provide specific information on the relative magnitude of these expected changes by industry and geography, and the expected time horizon for their impact to be felt on job functions, employment levels and skills. . Table 3: Significance of drivers of change, by industry Share of respondents rating driver as top trend, % BAS CON EN FS HE ICT MEI MOB PS OVERALL Changing nature of work, flexible work 46 42 46 26 20 36 36 35 63 44 Mobile internet, cloud technology 8 17 0 41 50 69 57 16 38 34 Processing power, Big Data 5 8 4 44 20 44 36 6 40 26 Middle class in emerging markets 15 42 0 41 40 8 21 39 13 23 New energy supplies and technologies 38 21 71 3 10 17 0 26 5 22 Climate change, natural resources 49 21 50 3 0 8 7 32 8 23 Geopolitical volatility 28 25 29 26 0 3 14 16 10 21 Consumer ethics, privacy issues 3 21 8 18 20 31 21 10 20 16 Internet of Things 8 13 4 12 10 33 14 6 15 14 Longevity, ageing societies 13 17 13 9 40 14 14 3 13 14 Young demographics in emerging markets 10 17 17 24 10 3 21 13 8 13 Sharing economy, crowdsourcing 3 4 4 18 10 11 21 6 25 12 Women's economic power, aspirations 10 21 13 9 10 3 7 6 15 12 Robotics, autonomous transport 15 8 4 3 0 0 7 29 5 9 Rapid urbanization 13 4 13 3 0 6 14 10 8 8 Adv. manufacturing, 3D printing 10 4 8 0 0 6 0 16 3 6 Artificial intelligence 5 0 8 3 0 6 7 16 5 7 Adv. materials, biotechnology 8 4 0 3 30 0 0 13 0 6 Driver of change Source: Future of Jobs Survey, World Economic Forum. Note: Names of drivers have been abbreviated to ensure legibility. Technological, Demographic and Socio-Economic Trends Affecting Business Models Figure 2 lists the major industry drivers of change and disruptions to business models identified by the senior executives in our survey, ranked according to the share of respondents who expected each trend to be among the top trends impacting their industry by the year 2020. Table 2 provides a short description of each trend and the median time horizon by which it is expected to start impacting the respondent’s industry. Collectively, technological disruptions are seen as very significant drivers of industrial change by the respondents. Among these, growth in cheap computing power and the ubiquity of the mobile internet have already had widespread impact on existing business models.

Additionally, even technological trends whose potentially far-ranging implications have not yet fully materialized—such as 3D printing, artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things—are expected to be well underway in specific industries in the years leading up to 2020. Industry codes Code Industry BAS Basic and Infrastructure CON Consumer EN Energy FS Financial Services & Investors HE Healthcare ICT Information and Communication Technology MEI Media, Entertainment and Information MOB Mobility PS Professional Services Demographic and socio-economic shifts are expected to have nearly as strong an impact on business models and organizational structures as technological change. Application of technology has already changed when and where work is done in practically every industry as workplaces of the industrial age give way to work practices of the digital age, including remote work, flexible work and The Future of Jobs Report | 9 . Figure 3: Timeframe to impact industries, business models Impact felt already 2015–2017 2018–2020 »» Rising geopolitical volatility »» Mobile internet and cloud technology »» Advances in computing power and Big Data »» Crowdsourcing, the sharing economy and peer-to-peer platforms »» Rise of the middle class in emerging markets »» Young demographics in emerging markets »» Rapid urbanization »» Changing work environments and flexible working arrangements »» Climate change, natural resource constraints and the transition to a greener economy »» New energy supplies and technologies »» The Internet of Things »» Advanced manufacturing and 3D printing »» Longevity and ageing societies »» New consumer concerns about ethical and privacy issues »» Women’s rising aspirations and economic power »» Advanced robotics and autonomous transport »» Artificial intelligence and machine learning »» Advanced materials, biotechnology and genomics on-demand work. The rising middle class in emerging markets, the need to transition towards an environmentally sustainable economy and increased geopolitical volatility are all seen as major organizational drivers of change. Changing values and the growing ability of consumers to express these values are also transforming business models and employment. The rising role and importance of women in the economy is transforming not only the composition of the talent pool but also the nature of products catering to them specifically—and by extension the skills profiles of the jobs required.

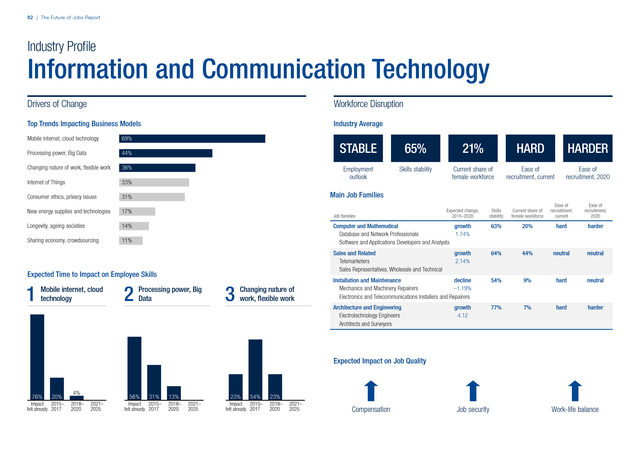

Longevity and population ageing in advanced economies—and the opportunities and challenges it presents—are also expected to have an impact on business models, and by extension talent needs, in addition to changing the composition of the talent pool in most developed economies in particular. Industry- and Country-Level Change A number of drivers of change will have an acute impact within specific industries. At the industry level, for example, new energy supplies and technologies will have a particular impact on the Energy, Basic and Infrastructure and Mobility industries. Processing power and Big Data will have an especially strong impact on Information and Communication Technology, Financial Services and Professional Services. The rising middle class in emerging markets will have the largest effect on Consumer, Financial Services and Mobility. Consumer ethics and privacy issues will have a significant impact on the Consumer, Financial Services and Information and Communication Technology sector (see Table 3). At the country level, expectations regarding the nature of upcoming disruptions are shaped by the demographic, economic and technological development of the country in question.

Overall, changing and flexible work is seen as the most significant driver of change in advanced economies, whereas the rising middle class takes this role in emerging markets. New energy supplies and technologies are expected to play the largest role in the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council, while climate change adaptation is seen as a particularly major driver in Germany. A number 10 | The Future of Jobs Report of developing countries expect particularly large impact from the mobile internet given that the technology has the potential to bring millions of formerly unconnected workers and consumers into the formal economy for the first time. For further details, please also refer to the Country Profiles in Part 2 of this Report. Expected Timeframe The time-to-impact trajectory of certain drivers of change differs between industries and is shaped by the specific nature of each sector’s current business model.

For example, there is a wide variety of opinion among Chief Human Resources Officers regarding the immediacy of the impact of artificial intelligence and robotics on employment and skills.5 However, regardless of the specific industry or driver of change, it is clear that the overall pace of industry transformation is wholly unprecedented. Disruptive changes to industry sectors are already re-configuring business models and skill sets—and will do so at an accelerated pace in the next five years. The current anxious debate about the long-term impact of artificial intelligence and robotics notwithstanding, our focus is on today’s workforce and talent strategies and how they can contribute to successfully managing this transition. EMPLOYMENT TRENDS Recent discussions about the employment impact of disruptive change have often been polarized between those who foresee limitless opportunities in newly emerging job categories and prospects that improve workers’ productivity and liberate them from routine work, and those that foresee massive labour substitution and displacement of jobs. Academics, chief executives and labour leaders hold strong and diverse views on the debate, as do policymakers.6 It is clear from our data that while forecasts vary by industry and region, momentous change is underway and that, ultimately, it is our actions today that will determine whether that change mainly results in massive displacement of workers or the emergence of new opportunities.

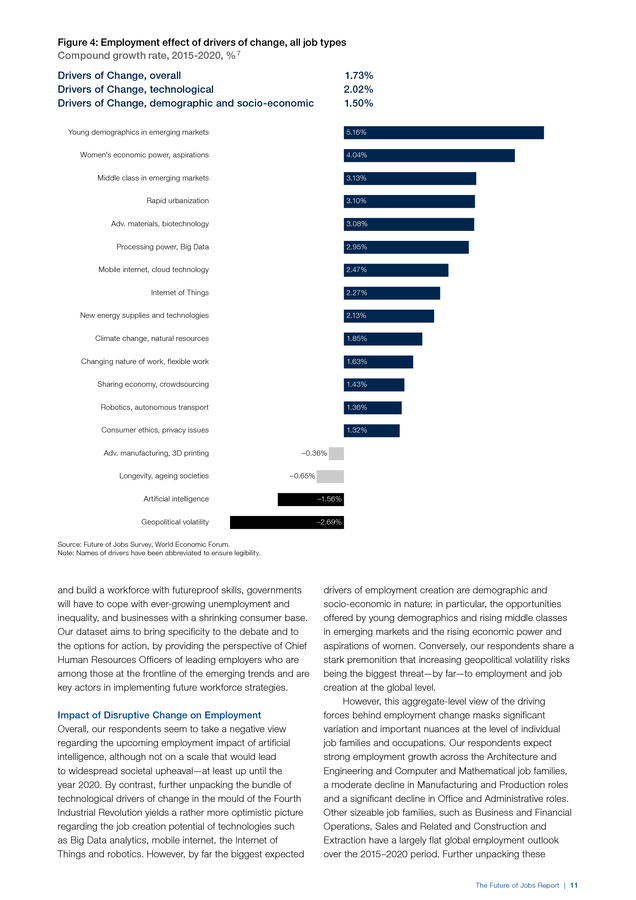

Without urgent and targeted action today to manage the near-term transition . Figure 4: Employment effect of drivers of change, all job types Compound growth rate, 2015-2020, % 7 Drivers of Change, overall Drivers of Change, technological Drivers of Change, demographic and socio-economic 1.73% 2.02% 1.50% Young demographics in emerging markets 5.16% Women’s economic power, aspirations 4.04% Middle class in emerging markets 3.13% Rapid urbanization 3.10% Adv. materials, biotechnology 3.08% Processing power, Big Data 2.95% Mobile internet, cloud technology 2.47% Internet of Things 2.27% New energy supplies and technologies 2.13% Climate change, natural resources 1.85% Changing nature of work, flexible work 1.63% Sharing economy, crowdsourcing 1.43% Robotics, autonomous transport 1.36% Consumer ethics, privacy issues 1.32% Adv. manufacturing, 3D printing Longevity, ageing societies –0.36% –0.65% Artificial intelligence –1.56% Geopolitical volatility –2.69% Source: Future of Jobs Survey, World Economic Forum. –0.02 Note: Names of drivers have been abbreviated to–0.03 legibility. ensure –0.01 and build a workforce with futureproof skills, governments will have to cope with ever-growing unemployment and inequality, and businesses with a shrinking consumer base. Our dataset aims to bring specificity to the debate and to the options for action, by providing the perspective of Chief Human Resources Officers of leading employers who are among those at the frontline of the emerging trends and are key actors in implementing future workforce strategies. Impact of Disruptive Change on Employment Overall, our respondents seem to take a negative view regarding the upcoming employment impact of artificial intelligence, although not on a scale that would lead to widespread societal upheaval—at least up until the year 2020. By contrast, further unpacking the bundle of technological drivers of change in the mould of the Fourth Industrial Revolution yields a rather more optimistic picture regarding the job creation potential of technologies such as Big Data analytics, mobile internet, the Internet of Things and robotics.

However, by far the biggest expected 0.00 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 drivers of employment creation are demographic and socio-economic in nature; in particular, the opportunities offered by young demographics and rising middle classes in emerging markets and the rising economic power and aspirations of women. Conversely, our respondents share a stark premonition that increasing geopolitical volatility risks being the biggest threat—by far—to employment and job creation at the global level. However, this aggregate-level view of the driving forces behind employment change masks significant variation and important nuances at the level of individual job families and occupations. Our respondents expect strong employment growth across the Architecture and Engineering and Computer and Mathematical job families, a moderate decline in Manufacturing and Production roles and a significant decline in Office and Administrative roles. Other sizeable job families, such as Business and Financial Operations, Sales and Related and Construction and Extraction have a largely flat global employment outlook over the 2015–2020 period.

Further unpacking these The Future of Jobs Report | 11 0.06 . Table 4: Employment effect of drivers of change, by job family Compound growth rate, 2015-2020, % Job family/Driver of change Computer and Mathematical Employment outlook 3.21% Job family/Driver of change Sales and Related Employment outlook 0.46% Rapid urbanization 6.11% Processing power, Big Data 1.25% Middle class in emerging markets 5.00% Sharing economy, crowdsourcing 0.58% Changing nature of work, flexible work 4.94% Mobile internet, cloud technology 0.43% Sharing economy, crowdsourcing 4.88% Internet of Things –0.89% Processing power, Big Data 4.59% Middle class in emerging markets –1.14% Internet of Things 4.54% Consumer ethics, privacy issues –1.28% Geopolitical volatility 3.89% Geopolitical volatility –1.50% Mobile internet, cloud technology 3.71% Changing nature of work, flexible work –1.51% Consumer ethics, privacy issues 2.40% New energy supplies and technologies –1.58% Architecture and Engineering 2.71% Installation and Maintenance –0.15% Middle class in emerging markets 5.88% Climate change, natural resources Robotics, autonomous transport 4.49% Changing nature of work, flexible work 0.45% Climate change, natural resources 3.68% Mobile internet, cloud technology –3.89% Internet of Things 3.54% Adv. manufacturing, 3D printing 3.33% Internet of Things Construction and Extraction 3.00% –8.00% –0.93% Changing nature of work, flexible work 3.18% New energy supplies and technologies 1.38% New energy supplies and technologies 2.25% Climate change, natural resources 0.38% 1.33% Geopolitical volatility –0.07% 0.97% Changing nature of work, flexible work –0.11% Geopolitical volatility Management Young demographics in emerging markets 2.14% Geopolitical volatility 1.67% Mobile internet, cloud technology 0.95% New energy supplies and technologies 1.44% Middle class in emerging markets –0.83% Processing power, Big Data 1.39% Geopolitical volatility –1.00% Changing nature of work, flexible work 0.90% Middle class in emerging markets 0.72% Mobile internet, cloud technology 0.62% Climate change, natural resources 0.40% Longevity, ageing societies 0.23% Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports and Media Manufacturing and Production Adv. materials, biotechnology –1.03% –1.63% 0.67% Robotics, autonomous transport –0.83% New energy supplies and technologies –1.81% Middle class in emerging markets –2.16% 0.70% Climate change, natural resources –2.45% Sharing economy, crowdsourcing 3.11% Geopolitical volatility –2.47% Middle class in emerging markets 1.96% Changing nature of work, flexible work –2.99% Changing nature of work, flexible work 1.88% Longevity, ageing societies –3.13% Young demographics in emerging markets 1.67% Adv. manufacturing, 3D printing –3.60% Business and Financial Operations Geopolitical volatility 1.59% Climate change, natural resources 1.39% Processing power, Big Data 1.34% Mobile internet, cloud technology 1.03% Consumer ethics, privacy issues 0.54% Office and Administrative –4.91% Changing nature of work, flexible work –2.77% New energy supplies and technologies –3.33% Mobile internet, cloud technology –5.82% Processing power, Big Data –6.06% Consumer ethics, privacy issues –6.18% Internet of Things –6.20% Rapid urbanization –6.36% Climate change, natural resources –6.67% Geopolitical volatility –9.72% Source: Future of Jobs Survey, World Economic Forum. Note: Names of drivers have been abbreviated to ensure legibility. expectations according to the factors driving employment change makes clear the true scale of impending industry and occupational transformation.

See Table 4 for details on these expectations. The expected global decline in total Manufacturing and Production roles is driven by labour-substituting technologies such as additive manufacturing and 3D printing as much as by more resource-efficient sustainable 12 | The Future of Jobs Report product use, lower demand growth in ageing societies and threats to global supply chains due to geopolitical volatility. Some cautious optimism is warranted due to increased manufacturing demand for advanced materials and comparatively favourable expectations around robotics, pointing to the latter’s potential for labour-complementing productivity enhancement rather than pure job replacement. . Conversely, 3D printing, resource-efficient sustainable production and robotics are all seen as strong drivers of employment growth in the Architecture and Engineering job family, in light of a continued and fast-growing need for skilled technicians and specialists to create and manage advanced and automated production systems. This is expected to lead to a transformation of manufacturing into a highly sophisticated sector where high-skilled engineers are in strong demand to make the industrial Internet of Things a reality. The fortunes of other job families due to these same factors are mixed. Installation and Maintenance jobs, for example, will see great productivity enhancements and strong growth in green jobs such as the installation, retrofitting, repair and maintenance of smart meters and renewable energy technologies in residential and office buildings, but—at an aggregate level—will also come faceto-face with the efficiency-saving and labour-substituting aspect of the Internet of Things. Similarly, despite some challenges, global demographics will sustain demand for Construction and Extraction jobs.

Resource-efficiency is expected to be another key driving factor for this job family, at least in the case of construction, in the creation of new and improvement of existing housing stock, often using new construction techniques, materials and approaches. Automation of checkout processes and smart inventory management through sensors and other applications of the Internet of Things are some of the factors expected to lead to a decrease in demand for traditional roles in the Sales and Related job family. Consumer ethics and green consumption practices are likewise anticipated to impact negatively on traditional roles in the job family, though perhaps with an upside for employees with skills in accrediting and advising on eco-labelled products. The strongest employment growth in the sector is expected to come from a continued shift towards online shopping and the application of Big Data analytics to derive and act upon insights from customer data and preferences to provide a personalised shopping experience. Two further job families with mainly flat aggregate employment outlooks over the coming years are Business and Financial Operations and Management.

Each is affected by a very wide range of factors, hinting at the scale of transformation and upskilling needs these job families will undergo over the coming years. Strong employment growth in the Computer and Mathematical job family is driven by trends beyond technology, such as rapid urbanization in developing countries, as well as by disruptions that negatively affect the employment outlook in other job families, such as geopolitical volatility and privacy issues—as companies from virtually all industries seek to recruit specialists that can help them apply tools such as Big Data analytics and data visualization to better understand and cope with these issues. The biggest employment decline of any job family is expected in Office and Administrative roles, which are expected to be negatively affected by a perfect storm of technological trends that have the potential to make many of them redundant, such as mobile internet and cloud technology, Big Data analytics and the Internet of Things, but also factors such as climate change and resource efficiency and workplace flexibility that undermine the rationale for maintaining a large workforce within these roles. Interestingly, our respondents expect a comparatively small employment impact from two disruptions that currently receive significant attention. Where it is mentioned, the artificial intelligence and machine learning driver is expected to lead to negative employment outcomes in job families such as Education and Training, Legal and Business and Financial Operations. However, it appears our respondents do not believe that these technologies will have advanced significantly enough by the year 2020 to have a more widespread impact on global employment levels.

Similarly, the sharing economy may have the potential to radically transform the way work is organized and regulated in certain job families, with all the opportunities and challenges this entails; but where it is mentioned as a driver of change to employment, its effect is largely seen as benign in the next five years. Our analysis reveals that upcoming disruptions to the employment landscape are going to be a lot more complex and multi-faceted than conveyed by a narrow focus only on automation, and that we must act within the current window offered by the varying speeds of technological transformations to prepare. Global Net Employment Effects The survey results provide direct information on the expected relative employment changes to job families over the period 2015–2020. It is possible to extrapolate from these values the estimated numbers of jobs created or lost in absolute terms worldwide.

Between them, the 15 economies covered by our data account for about 1.86 billion workers, approximately 65% of the world’s total workforce. Using the standardized occupational classification behind our research framework, we have estimated the total number of people employed in any given job family in each of our focus countries (although for China, which accounts for 770 million workers out of our total, this data is unfortunately not available in a directly comparable format8).Therefore, we can give an estimate of the net effect on global employment of the trends and disruptions anticipated by the respondents covered by our Report. According to these calculations, current trends could lead to a net employment impact of more than 5.1 million jobs lost to disruptive labour market changes over the period 2015–2020, with a total loss of 7.1 million jobs— two thirds of which are concentrated in the Office and Administrative job family—and a total gain of 2 million jobs, in several smaller job families. A number of conclusions stand out: • The global workforce is expected by our respondents to experience significant churn between job families and functions, with administrative and routine white‑collar office functions at risk of being decimated and strong growth in Computer and Mathematical The Future of Jobs Report | 13 .

Figure 5: Total workforce by job family Employees (thousands, all focus countries) 264,365 Farming, Fishing and Forestry 98,723 Manufacturing and Production 96,928 Office and Administrative 89,613 Hospitality and Food Related 79,619 and Architecture and Engineering related fields. Manufacturing and Production roles are also expected to see a further bottoming out but might have the worst behind them and still retain relatively good potential for upskilling, redeployment and productivity enhancement through technology rather than pure substitution. Transportation and Logistics 70,282 Business and Financial Operations 65,787 Sales and Related 55,266 Personal Care and Service 53,404 Construction and Extraction 42,838 Management 38,727 Community, Social and Protective Services 26,887 Installation and Maintenance 18,799 Healthcare Practitioners and Technicians 15,663 Life, Physical, and Social sciences 14,659 Education and Training 14,628 Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports and Media 12,605 Computer and Mathematical 12,511 Architecture and Engineering 6,550 Legal 14 | The Future of Jobs Report • Employment growth is expected to derive disproportionately from smaller, generally high-skilled job families that will be unable to absorb job losses coming from other parts of the labour market. Even if they could, significant reskilling would be needed. This factor plus the increase in global unemployment due to global population growth and slow job creation over the period 2015-20199 leaves no room for complacency. • Once emerging markets and developing countries are added into the equation, any discussion of the Future of Jobs remains incomplete without recognizing that a significant share of the global workforce remains employed in agriculture, about which both current technology optimists and alarmists have comparatively little to say. Similarly, a potential field of employment growth around which our survey yielded only limited data points concerns the Personal Care and Service job family, since jobs in this field are not typically found on a large scale among large multinational employers.10 Indeed, there is cause for optimism about growth in these roles as demand for such services grows due to demographic and social factors. • There is a strong gender dimension to expected employment changes whereby, notably, gender gaps appear to be more pronounced within both high growth and declining job families. For example, women make up low numbers in the fast-growing STEM job families, pointing, on current trends, to a deteriorating gender gap over time; but also low numbers within job families such as Manufacturing and Production or Construction and Extraction, where expected job losses will disproportionately affect men.

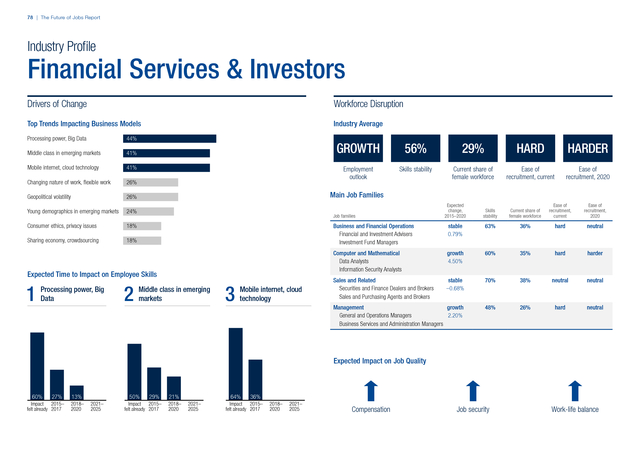

However, female employment is also concentrated in low-growth or declining job families such as Sales, Business and Financial Operations and Office and Administrative, indicating, if our respondents’ expectations come to pass, a possible reversal of some of the gains made in workplace gender parity over the past decade. Employment Trends by Industry From an industry-level perspective, there is a modestly positive outlook for employment across most sectors over the 2015–2020 period. However, underneath this aggregate outlook there is once again significant relative growth in some job families and significant relative decline in others, resulting from the accelerating pace of transformation within many industries. For further details, please also refer to the Industry Profiles in Part 2 of the Report. .

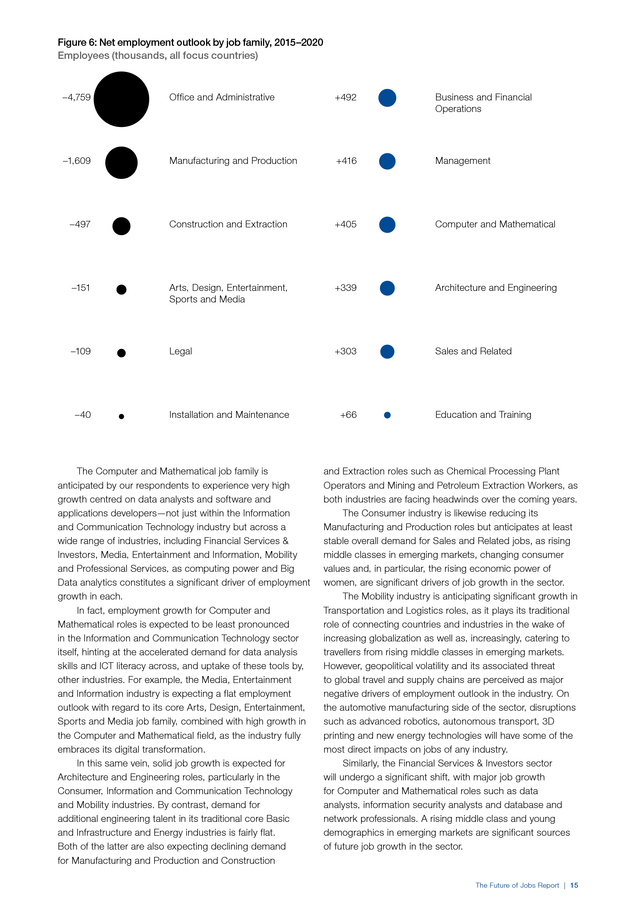

Figure 6: Net employment outlook by job family, 2015–2020 Employees (thousands, all focus countries) –4,759 Office and Administrative +492 Business and Financial Operations –1,609 Manufacturing and Production +416 Management –497 Construction and Extraction +405 Computer and Mathematical –151 Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports and Media +339 Architecture and Engineering –109 Legal +303 Sales and Related –40 Installation and Maintenance The Computer and Mathematical job family is anticipated by our respondents to experience very high growth centred on data analysts and software and applications developers—not just within the Information and Communication Technology industry but across a wide range of industries, including Financial Services & Investors, Media, Entertainment and Information, Mobility and Professional Services, as computing power and Big Data analytics constitutes a significant driver of employment growth in each. In fact, employment growth for Computer and Mathematical roles is expected to be least pronounced in the Information and Communication Technology sector itself, hinting at the accelerated demand for data analysis skills and ICT literacy across, and uptake of these tools by, other industries. For example, the Media, Entertainment and Information industry is expecting a flat employment outlook with regard to its core Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports and Media job family, combined with high growth in the Computer and Mathematical field, as the industry fully embraces its digital transformation. In this same vein, solid job growth is expected for Architecture and Engineering roles, particularly in the Consumer, Information and Communication Technology and Mobility industries. By contrast, demand for additional engineering talent in its traditional core Basic and Infrastructure and Energy industries is fairly flat. Both of the latter are also expecting declining demand for Manufacturing and Production and Construction +66 Education and Training and Extraction roles such as Chemical Processing Plant Operators and Mining and Petroleum Extraction Workers, as both industries are facing headwinds over the coming years. The Consumer industry is likewise reducing its Manufacturing and Production roles but anticipates at least stable overall demand for Sales and Related jobs, as rising middle classes in emerging markets, changing consumer values and, in particular, the rising economic power of women, are significant drivers of job growth in the sector. The Mobility industry is anticipating significant growth in Transportation and Logistics roles, as it plays its traditional role of connecting countries and industries in the wake of increasing globalization as well as, increasingly, catering to travellers from rising middle classes in emerging markets. However, geopolitical volatility and its associated threat to global travel and supply chains are perceived as major negative drivers of employment outlook in the industry. On the automotive manufacturing side of the sector, disruptions such as advanced robotics, autonomous transport, 3D printing and new energy technologies will have some of the most direct impacts on jobs of any industry. Similarly, the Financial Services & Investors sector will undergo a significant shift, with major job growth for Computer and Mathematical roles such as data analysts, information security analysts and database and network professionals.

A rising middle class and young demographics in emerging markets are significant sources of future job growth in the sector. The Future of Jobs Report | 15 . Table 5: Employment effect of drivers of change, by industry Compound growth rate, 2015-2020, % Industry/Driver of change Basic and Infrastructure Employment outlook 0.61% Industry/Driver of change Information and Communication Technology Employment outlook 2.91% Rapid urbanization 7.00% Processing power, Big Data Middle class in emerging markets 3.33% Mobile internet, cloud technology 4.78% New energy supplies and technologies 2.00% Consumer ethics, privacy issues 3.33% Climate change, natural resources 1.39% New energy supplies and technologies 2.50% Changing nature of work, flexible work 0.29% Internet of Things 2.27% Robotics, autonomous transport 0.00% Changing nature of work, flexible work 2.08% Longevity, ageing societies –7.00% Longevity, ageing societies –1.25% Geopolitical volatility –7.27% Media, Entertainment and Information 5.00% 2.31% 1.72% Processing power, Big Data Women's economic power, aspirations 3.75% Mobile internet, cloud technology 3.57% Consumer ethics, privacy issues 2.00% Changing nature of work, flexible work –2.00% Changing nature of work, flexible work 1.50% Middle class in emerging markets 1.25% Climate change, natural resources 2.50% Climate change, natural resources 1.25% New energy supplies and technologies 2.50% New energy supplies and technologies 1.00% Middle class in emerging markets 2.27% Geopolitical volatility 0.00% Robotics, autonomous transport 1.25% 1.54% Artificial intelligence 1.25% New energy supplies and technologies 2.19% Mobile internet, cloud technology 1.00% Changing nature of work, flexible work 1.00% Adv. manufacturing, 3D printing 1.00% Climate change, natural resources 0.83% Changing nature of work, flexible work 0.56% Geopolitical volatility –5.00% Geopolitical volatility –6.00% 1.54% Professional Services 2.45% Consumer Energy Financial Services & Investors Mobility 8.00% 1.61% Young demographics in emerging markets 6.25% Women's economic power, aspirations 5.00% Middle class in emerging markets 5.00% Middle class in emerging markets 5.00% Processing power, Big Data 1.54% Changing nature of work, flexible work 4.00% Mobile internet, cloud technology 1.15% Processing power, Big Data 2.35% Sharing economy, crowdsourcing 0.83% Mobile internet, cloud technology 2.14% Consumer ethics, privacy issues 0.83% Sharing economy, crowdsourcing 1.67% Changing nature of work, flexible work 0.63% Internet of Things 1.00% –2.22% Consumer ethics, privacy issues 0.71% –0.37% Longevity, ageing societies 0.00% Geopolitical volatility Healthcare Mobile internet, cloud technology –3.00% –3.00% Source: Future of Jobs Survey, World Economic Forum. Note: Names of drivers have been abbreviated to ensure legibility. Many industry observers expect a substantial increase in the number of jobs in the Healthcare sector due to demographic trends such a longevity and ageing populations in advanced economies. However, our survey respondents expect a stable employment outlook for the industry over the coming five years—and a net negative impact on the number of jobs from disruptions such as mobile internet and cloud technology, enabling widespread application of telemedicine. What seems certain is that the skills profile of many jobs in the sector will change significantly. Our respondents anticipate that the Professional Services industry will experience employment growth over the 2015–2020 period, particularly in data analytics roles, especially as the consulting arm of the sector experiences growth by advising all others on their respective transformations.

Accordingly, factors affecting jobs in the industry are influenced by those affecting all the others. With regards to business models in the Professional 16 | The Future of Jobs Report Services industry itself, some of the major influences will be automation or globalized crowdsourcing via online platforms of high-skilled but repetitive work processes, leading to increased off-shoring of back office roles and a rise in timelimited, project-based contracts. New and Emerging Roles Our research also explicitly asked respondents about new and emerging job categories and functions that they expect to become critically important to their industry by the year 2020, and where within their global operations they would expect to locate such roles. Two job types stand out due to the frequency and consistency with which they were mentioned across practically all industries and geographies. The first are data analysts, as already frequently mentioned above, which companies expect will help them make sense and derive insights from the torrent of data generated by the technological disruptions referenced above. The second .

are specialized sales representatives, as practically every industry will need to become skilled in commercializing and explaining their offerings to business or government clients and consumers, whether due to the innovative technical nature of the products themselves, due to their being targeted at new client types with which the company is not yet familiar, or both. Other new specialties frequently mentioned include new types of human resources and organizational development specialists, engineering specialties such as materials, bio-chemicals, nanotech and robotics, regulatory and government relations specialists, geospatial information systems experts and commercial and industrial designers. A particular need is also seen in industries as varied as Energy and Media, Entertainment and Information for a new type of senior manager who will successfully steer companies through the upcoming change and disruption. Once more, there is a gender gap dimension to these findings, as the growth of new and emerging roles in computer, technology and engineering-related fields is outpacing the rate at which women are currently entering those types of jobs—putting them at risk of missing out on tomorrow’s best job opportunities and aggravating hiring processes for companies due to a more restricted talent pool. We also asked respondents to identify roles where there may be consistent decline. Across a wide range of sectors including Basic and Infrastructure, Energy, Financial Services & Investors, Information and Communication Technology as well as Professional Services, Office and Administrative functions are poised for major redundancies. One particular set of jobs affected by this, for example, are customer service roles, which will become obsolete due to mobile internet technology to monitor service quality online as a means of maintaining effective customer relationship management. Changes in Job Quality and Ease of Recruitment In addition to the quantity of jobs, disruptive changes to industries and business models will also affect the quality, skills requirements and day-to-day content of virtually every job. Overall, our respondents expect a relative increase in compensation for in-demand jobs in every industry surveyed, in line with increased productivity and skills requirements. They also expect an overall increase in work-life balance in all industries except the Consumer sector, where the outlook for this dimension remains stable.

Expectations are less clear with regard to overall job security, which is expected to increase in the Energy, Financial Services, Healthcare and Information and Communication Technology sectors, but to decrease in the Basic and Infrastructure, Consumer, Media, Entertainment and Information, Mobility and Professional Services industries. It is important to note that these are aggregate results for entire industries. For example, Energy includes renewables and utilities in addition to oil and gas.

See Part 2 for further details in the Industry Profiles. An additional dimension to consider is the general trend towards flexible work, identified by our respondents as one of the biggest drivers of transformation of business models in many industries and therefore also one of the topmost concerns at the national level in many of the Report’s focus countries. Telecommuting, co-working spaces, virtual teams, freelancing and online talent platforms are all on the rise, transcending the physical boundaries of the office or factory floor and redefining the boundary between one’s job and private life in the process. Modern forms of workers’ organization, such as digital freelancers’ unions, and updated labour market regulations are beginning to emerge to complement these new organizational models.

The challenge for employers, individuals and governments alike is going to be to work out ways and means to ensure that the changing nature of work benefits everyone. Given the overall disruption industries are experiencing, it is not surprising that, with current trends, competition for talent in in-demand job families such as Computer and Mathematical and Architecture and Engineering and other strategic and specialist roles will be fierce, and finding efficient ways of securing a solid talent pipeline a priority for virtually every industry. Most strategic and specialist roles across industries, countries and job families are already perceived as hard to recruit for currently and—with few exceptions—the situation is expected to worsen significantly over the 20152020 period, notably in the Consumer, Information and Communication Technology, Basic and Infrastructure and Media, Entertainment and Information industries (Figure 7). Across key job families, recruitment is currently perceived as most difficult for traditional middle-skilled and skilled trade occupations, such as in Installation and Maintenance, as well as for Architecture and Engineering and Computer and Mathematical roles. By 2020 our respondents expect that it will be significantly more difficult to recruit specialists across most job families, particularly so for Computer and Mathematical roles, given the war for talent that is already shaping up in this field today. Interestingly, Office and Administrative roles will be among the hardest jobs to recruit for in absolute terms by 2020, presumably partly due to the perceived unattractiveness of the field, if current employment projections come to pass, and the very different core skills requirements this field may have going forward. By contrast, recruitment for standard white collar Business and Financial Operations roles is currently perceived as comparatively easy, and the talent pipeline is expected to marginally improve even further in the future. There are significant variations in perceived ease of recruitment by geography, although finding specialists is expected to become more difficult across all selected economies over the 2015–2020 period.

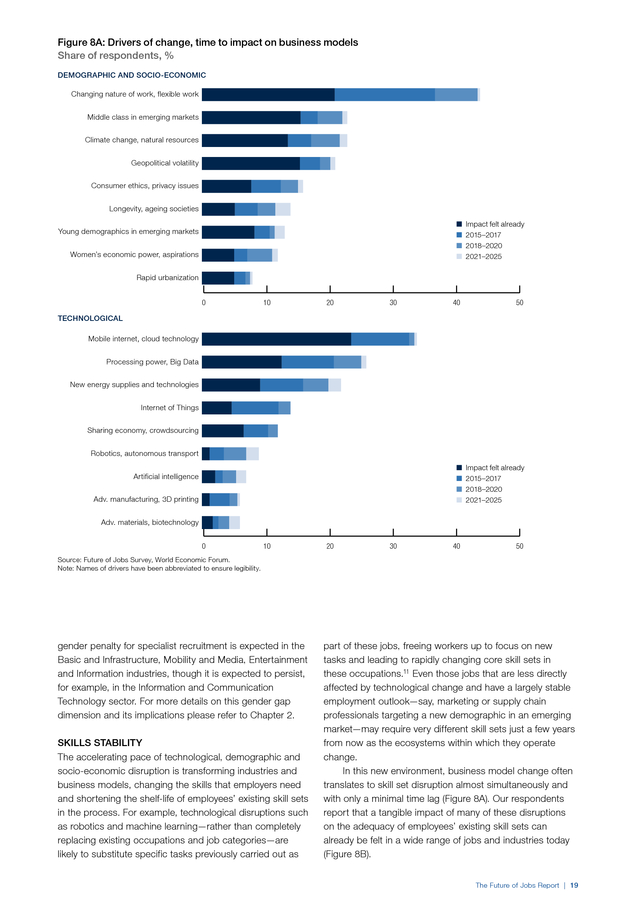

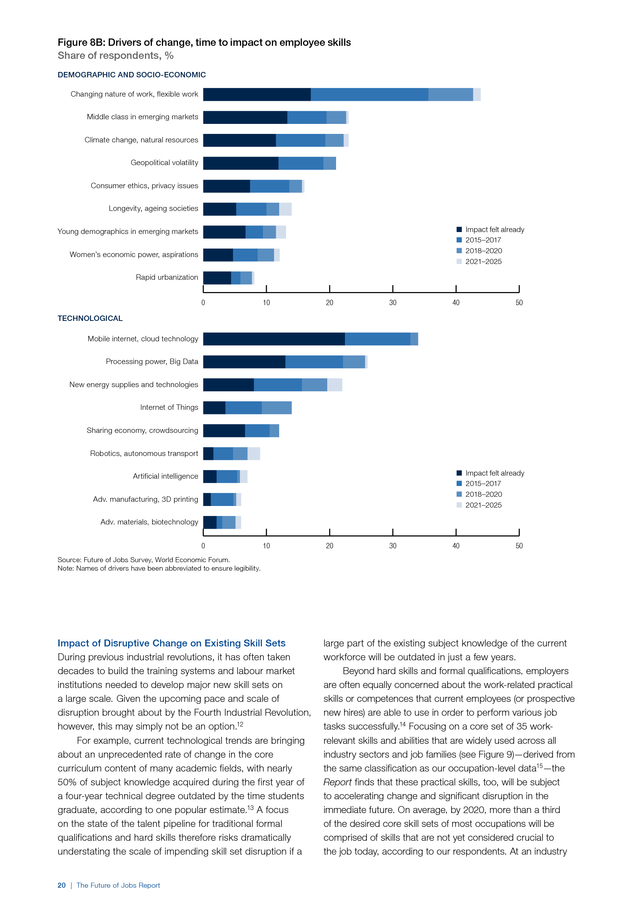

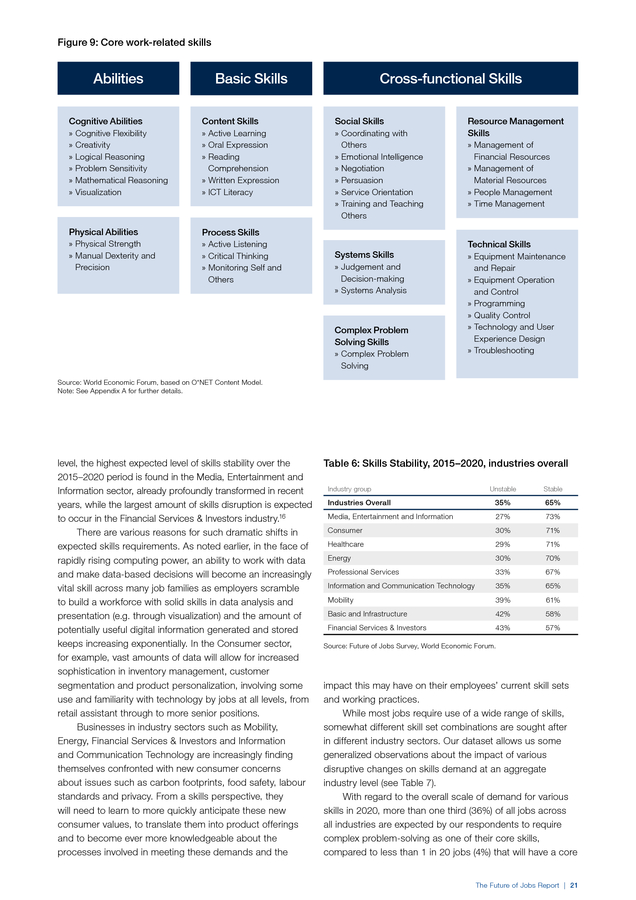

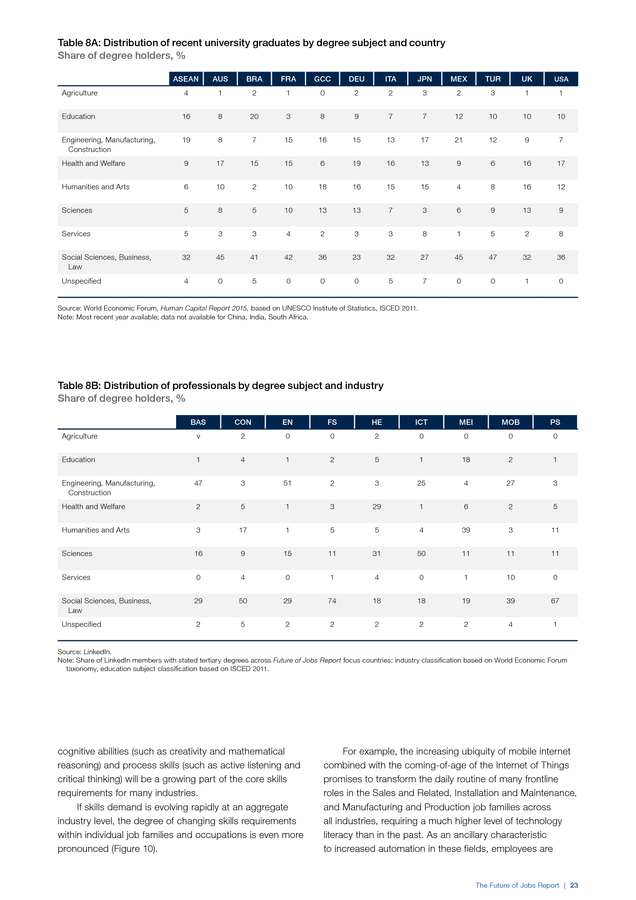

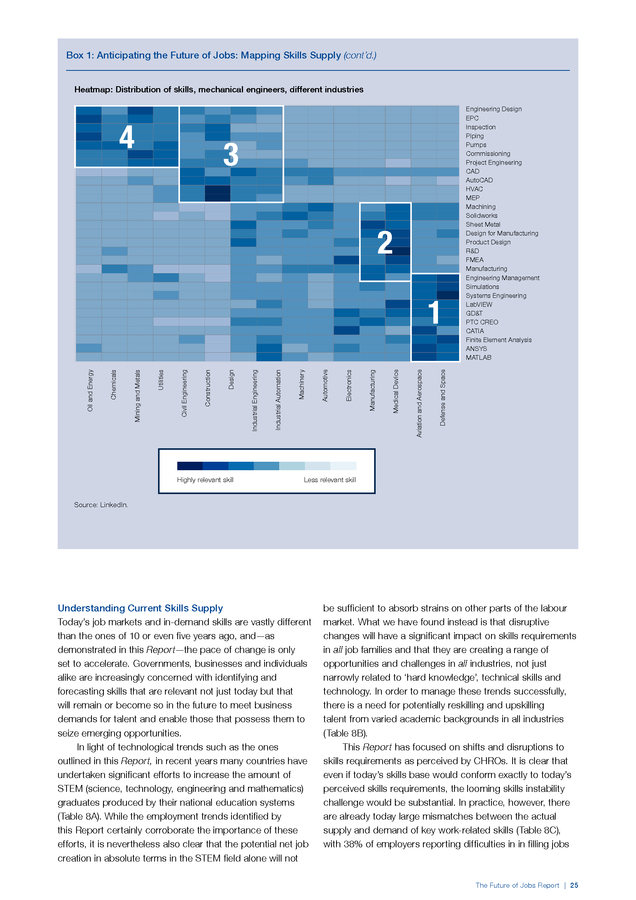

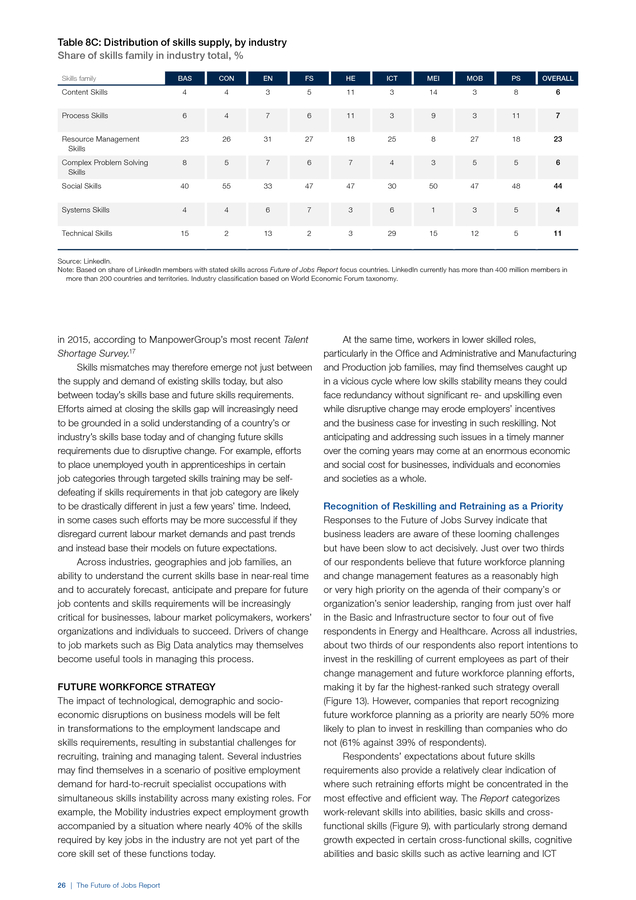

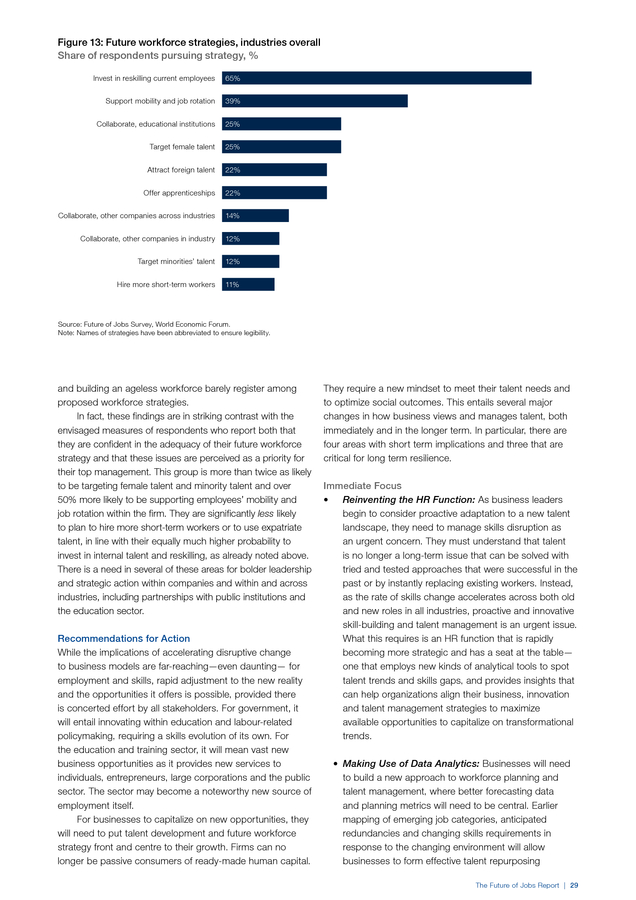

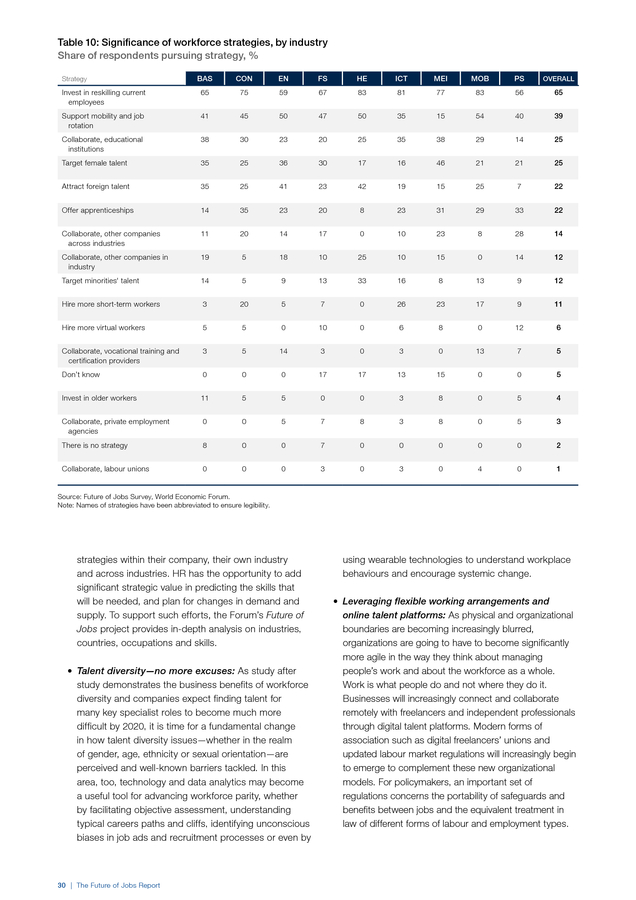

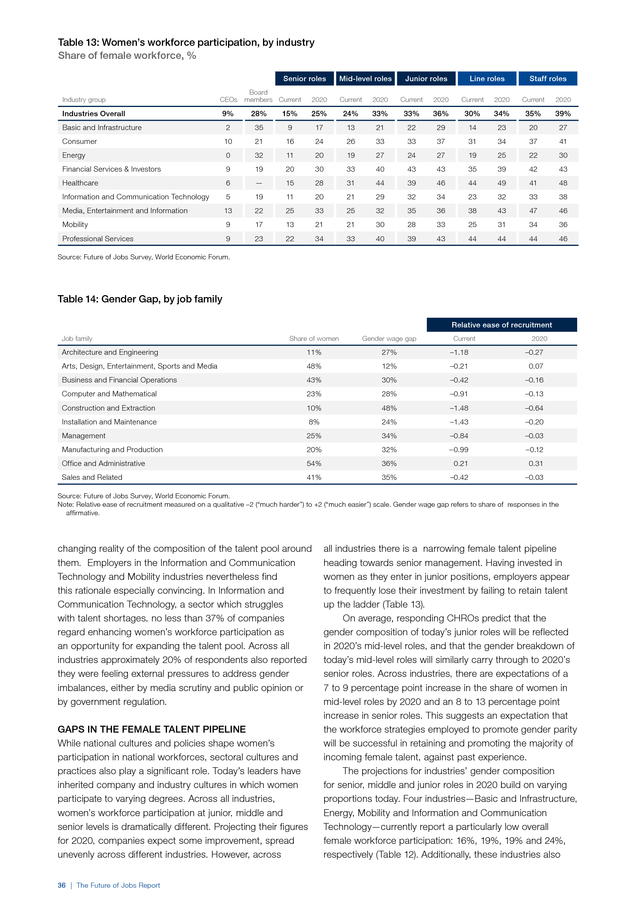

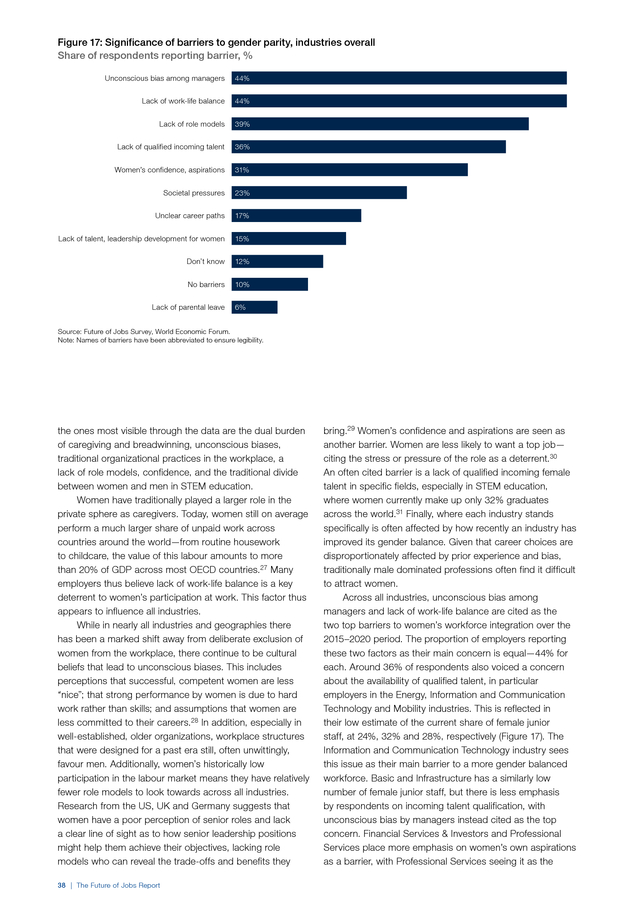

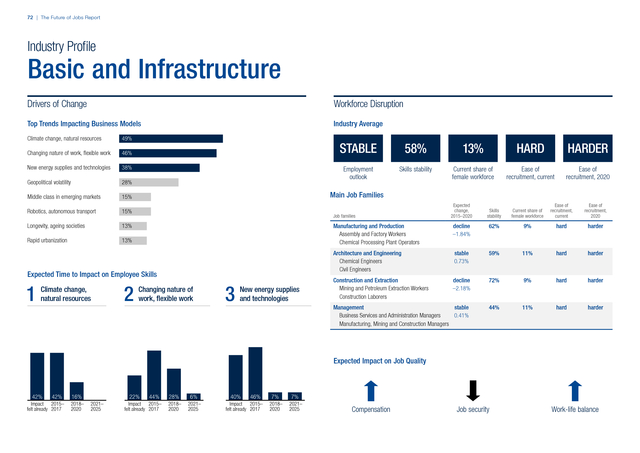

The situation will be particularly difficult in Japan, exacerbated by the country’s ageing demographics. Our respondents also note that whereas it is often harder to recruit women than men for many specialist roles, particularly for jobs concentrated in the Computer and Mathematical and Architecture and Engineering job families, this trend is expected to improve somewhat over the 2015–2020 period. The largest progress in overcoming this The Future of Jobs Report | 17 . Figure 7: Expected change in ease of recruitment, 2015–2020 Perception rating on a –2 (“very hard”) to +2 (“very easy”) scale INDUSTRIES 1.0 Average ease of recruitment 0.5 0.0 -0.5 –1.0 –0.5 –0.34 –0.14 –0.55 –0.49 –0.54 –0.63 –0.42 –1.5 –0.53 –2.0 Basic and Infrastructure Consumer Energy Financial Services & Investors Healthcare Information and Media, Communication Entertainment Technology and Information Mobility Professional Services JOB FAMILIES 1.0 0.5 Average ease of recruitment 0.02 0.0 –0.5 –0.67 –1.0 –0.44 –0.29 –0.70 –1.5 –0.34 –0.43 –0.58 –0.20 –1.00 –0.20 –2.0 Architecture Arts, Design, Business Computer Construction Installation and Entertainment, and and and and Engineering Sports Financial Mathematical Extraction Maintenance and Media Operations Manage- Manufacturing Life, Ofï¬ce Sales and ment and Physical, and Related Production and Administrative Social Sciences COUNTRY/REGION 1.0 0.5 Average ease of recruitment n/a 0.04 0.0 –0.5 –1.0 –0.44 –0.41 –0.62 –0.06 –0.50 –0.39 –0.65 –0.71 –0.21 –0.67 –0.13 –1.5 –0.50 –2.0 –0.85 ASEAN Australia Brazil China Source: Future of Jobs Survey, World Economic Forum. 18 | The Future of Jobs Report France GCC Germany India Italy Japan Mexico South Africa Turkey United United Kingdom States . Figure 8A: Drivers of change, time to impact on business models Share of respondents, % DEMOGRAPHIC AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC Changing nature of work, flexible work Middle class in emerging markets Climate change, natural resources Geopolitical volatility Consumer ethics, privacy issues Longevity, ageing societies n Impact felt already n 2015–2017 n 2018–2020 n 2021–2025 Young demographics in emerging markets Women’s economic power, aspirations Rapid urbanization 0 10 20 30 40 50 TECHNOLOGICAL Mobile internet, cloud technology Processing power, Big Data New energy supplies and technologies Internet of Things Sharing economy, crowdsourcing Robotics, autonomous transport n Impact felt already n 2015–2017 n 2018–2020 n 2021–2025 Artificial intelligence Adv. manufacturing, 3D printing Adv. materials, biotechnology 0 10 20 30 40 50 Source: Future of Jobs Survey, World Economic Forum. Note: Names of drivers have been abbreviated to ensure legibility. gender penalty for specialist recruitment is expected in the Basic and Infrastructure, Mobility and Media, Entertainment and Information industries, though it is expected to persist, for example, in the Information and Communication Technology sector. For more details on this gender gap dimension and its implications please refer to Chapter 2. SKILLS STABILITY The accelerating pace of technological, demographic and socio-economic disruption is transforming industries and business models, changing the skills that employers need and shortening the shelf-life of employees’ existing skill sets in the process.